Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Genoa

View on Wikipedia

Genoa (/ˈdʒɛnoʊə/ JEN-oh-ə; Italian: Genova [ˈdʒɛːnova] ⓘ; Ligurian: Zêna [ˈzeːna])[a] is the sixth-largest city in Italy and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria. As of 2025, 564,919 people live within the city's administrative limits.[4] While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitants,[3] more than 1.5 million people live in the wider metropolitan area stretching along the Italian Riviera.[5]

Key Information

On the Gulf of Genoa in the Ligurian Sea, Genoa has historically been one of the most important ports on the Mediterranean: it is the busiest port in Italy and in the Mediterranean Sea and twelfth-busiest in the European Union.[6][7]

Genoa was the capital of one of the most powerful maritime republics for over seven centuries, from the 11th century to 1797.[8] Particularly from the 12th century to the 15th century, the city played a leading role in the history of commerce and trade in Europe, becoming one of the largest naval powers of the continent and considered among the wealthiest cities in the world.[9][10] It was also nicknamed la Superba ("the proud one") by Petrarch due to its glories on the seas and impressive landmarks.[11] The city has hosted massive shipyards and steelworks since the 19th century, and its solid financial sector dates back to the Middle Ages. The Bank of Saint George, founded in 1407, is the oldest known state deposit bank in the world and has played an important role in the city's prosperity since the middle of the 15th century.[12][13]

The historical centre, also known as old town, of Genoa is one of the largest and most-densely populated in Europe.[14] Part of it was also inscribed on the World Heritage List (UNESCO) in 2006 as Genoa: Le Strade Nuove and the system of the Palazzi dei Rolli. Genoa's historical city centre is also known for its narrow lanes and streets that the locals call "caruggi".[15] Genoa is also home to the University of Genoa, which has a history going back to the 15th century, when it was known as Genuense Athenaeum. The city's rich cultural history in art, music and cuisine allowed it to become the 2004 European Capital of Culture. It is the birthplace of Guglielmo Embriaco, Christopher Columbus, Andrea Doria, Niccolò Paganini, Giuseppe Mazzini, Renzo Piano and Grimaldo Canella, founder of the House of Grimaldi, among others.

Genoa, which forms the southern corner of the Milan-Turin-Genoa industrial triangle of Northwest Italy, is one of the country's major economic centres.[16][17] A number of leading Italian companies are based in the city, including Fincantieri, Leonardo,[18] Ansaldo Energia,[19] Ansaldo STS, Erg, Piaggio Aerospace, Mediterranean Shipping Company and Costa Cruises.

Etymology

[edit]The city's modern name may derive from the Latin word genu ([ˈɡe.nuː]; plural genua [ˈɡe.nu.aː]), meaning "knee". Some alternative origins for it are: the theonym of Janus, for Genoa, like he, has two faces: one looking at the sea and another turned to the mountains; or, the Latin word ianua ([ˈi̯aː.nu.a]), also related to the name of the god Janus, and meaning "door" or "passage". Besides those, the name may refer to the city's geographical position at the centre of the Ligurian coastal arch. The Latin name oppidum Genua ([ˈop.pi.dum ˈɡe.nu.a]; "Genoa town") is recorded by Pliny the Elder (Nat. Hist. 3.48), as part of the Augustean Regio IX Liguria.[20]

It could also have an Etruscan origin in the word Kainua, which meant "New City", based on an inscription on a pottery sherd reading Kainua, suggesting that the Latin name may be an alteration of an older Etruscan name with an original meaning of "new town".[21]

History

[edit]Prehistory and Roman times

[edit]The city's area has been inhabited since the fifth or fourth millennium BC, making it one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world.[22] In the fifth century BC the first town, or oppidum, was founded probably by the ancient Ligures (which gave the name to the modern region of Liguria) at the top of the hill today called Castello (Castle), which is now inside the medieval old town.[23][24] In this period the Genoese town, inhabited by the "Genuati" (a group of Ligure peoples), was considered "the emporium of the Ligurians", given its strong commercial character.[25]

The "Genoese oppidum" had an alliance with Rome through a foedus aequum (equal pact) in the course of the Second Punic War. The Carthaginians accordingly destroyed it in 209 BC. The town was rebuilt and, after the Carthaginian Wars ended in 146 BC, it received municipal rights. The original castrum then expanded towards the current areas of Santa Maria di Castello and the San Lorenzo promontory. Trade goods included skins, timber, and honey. Goods were moved to and from Genoa's hinterland, including major cities like Tortona and Piacenza. An amphitheater was also found there among other archaeological remains from the Roman period.[26]

Middle Ages to early modern period

[edit]5th to 10th centuries

[edit]After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Ostrogoths occupied Genoa. After the Gothic War, the Byzantines made it the seat of their vicar. When the Lombards invaded Italy in 568, Bishop Honoratus of Milan fled and held his seat in Genoa.[27] During this time and in the following century Genoa was little more than a small centre, slowly building its merchant fleet, which was to become the leading commercial carrier of the Western Mediterranean. In 934–35 the town was thoroughly sacked and burned by a Fatimid fleet under Ya'qub ibn Ishaq al-Tamimi.[28]

Rise of the Genoese Republic

[edit]

Genoa started expanding during the First Crusade. At the time the city had a population of about 10,000. Twelve galleys, one ship and 1,200 soldiers from Genoa joined the crusade. The Genoese troops, led by noblemen de Insula and Avvocato, set sail in July 1097.[29] The Genoese fleet transported and provided naval support to the crusaders, mainly during the siege of Antioch in 1098, when the Genoese fleet blockaded the city while the troops provided support during the siege.[29] In the siege of Jerusalem in 1099 Genoese crossbowmen led by Guglielmo Embriaco acted as support units against the defenders of the city.

The Republic's role as a maritime power in the Mediterranean region secured many favorable commercial treaties for Genoese merchants. They came to control a large portion of the trade of the Byzantine Empire, Tripoli (Libya), the Principality of Antioch, Cilician Armenia, and Egypt.[29] Although Genoa maintained free-trading rights in Egypt and Syria, it lost some of its territorial possessions after Saladin's campaigns in those areas in the late 12th century.[30][31]

13th and 14th centuries

[edit]The commercial and cultural rivalry of Genoa and Venice was played out through the thirteenth century. Thanks to the major role played by the Republic of Venice in the Fourth Crusade, Venetian trading rights were enforced in the eastern Mediterranean and Venice was able to gain control of a large portion of maritime commerce in the region.[30]

To regain control of local commerce, the Republic of Genoa allied with Michael VIII Palaiologos, emperor of Nicaea, who wanted to restore the Byzantine Empire by recapturing Constantinople. In March 1261 the treaty of the alliance was signed in Nymphaeum.[30] On 25 July 1261, Nicaean troops under Alexios Strategopoulos recaptured Constantinople.[30] As a result, the balance of favour tipped toward Genoa, which was granted free trade rights in the Nicene Empire.[30] The islands of Chios and Lesbos became commercial stations of Genoa as well as the city of Smyrna (Izmir). In the same century the Republic conquered many settlements in Crimea, known as Gazaria, where the Genoese colony of Caffa was established. The alliance with the restored Byzantine Empire increased the wealth and power of Genoa, and simultaneously decreased Venetian and Pisan commerce. The Byzantine Empire had granted the majority of free trading rights to Genoa.[32]

Around the 14th century, Genoa was also credited with the invention of blue jeans[citation needed]. Genoa's jean fabric was a fustian textile of "medium quality and of reasonable cost", very similar to cotton corduroy for which Genoa was famous, and was "used for work clothes in general". The Genoese navy equipped its sailors with jeans, as they needed a fabric which could be worn wet or dry.[33][34]

During the Catalan–Genoese War, Genoa was besieged and sacked by Guillem de Cervelló. As a result of the Genoese support to the Aragonese rule in Sicily, Genoa was granted free trading and export rights in the Kingdom. Genoese bankers also profited from loans to the new nobility of Sicily. Corsica was formally annexed in 1347.[35]

15th and 16th centuries

[edit]

In the 15th century two of the earliest banks in the world were founded in Genoa: the Bank of Saint George, founded in 1407, which was the oldest state deposit bank in the world at its closure in 1805 and the Monte di Pietà of Genoa founded in 1483. Christopher Columbus was born in Genoa c. 1451, and donated one-tenth of his income from the discovery of the Americas for Spain to the Bank of Saint George in Genoa for the relief of taxation on foods. Under the ensuing economic recovery, many aristocratic Genoese families, such as the Balbi, Doria, Grimaldi, Pallavicini, and Serra, amassed tremendous fortunes. According to Felipe Fernandez-Armesto and others, the practices Genoa developed in the Mediterranean (such as chattel slavery) were crucial in the exploration and exploitation of the New World.[36]

Thereafter, Genoa became something of an associate of the Spanish Empire, with Genoese bankers, in particular, financing many of the Spanish crown's foreign endeavors from their counting houses in Seville. Fernand Braudel has even called the period 1557 to 1627 the "age of the Genoese", "of a rule that was so discreet and sophisticated that historians for a long time failed to notice it" (Braudel 1984 p. 157). The Genoese bankers provided the unwieldy Habsburg system with fluid credit and a dependably regular income. But other historians have stressed how the Genoese participation in the Spanish Atlantic went well beyond financial flows, with Genoese merchants and entrepreneurs settling in different areas of the empire and building Genoese networks that lasted well into the 19th century.[37][38] In return the less dependable shipments of American silver were rapidly transferred from Seville to Genoa, to provide capital for further ventures. Genoa's trade, however, remained closely dependent on control of Mediterranean sealanes, and the loss of Chios to the Ottoman Empire (1566), struck a severe blow.[39] To help cope, Panama in the Americas was given as concession from the Spanish Empire to Genoa.[40]

17th century

[edit]

From the 17th century, the Genoese Republic started a period of slow decline. In May 1625 a French-Savoian army briefly laid siege to Genoa. Though it was eventually lifted with the aid of the Spanish, the French would later bombard the city in May 1684 for its support of Spain during the War of the Reunions.[41] In-between, a plague killed as many as half of the inhabitants of Genoa in 1656–57.[42]

18th century

[edit]In 1729, the Republic of Genoa had to cope with the beginning of the Corsican revolution for their independence. First led by Luiggi Giafferi and Giacinto Paoli, this conflict culminated after 26 years of struggle, costly in economic and military terms for the Republic of Genoa, in a self proclaimed Corsican Republic in 1755 under the leadership of Pasquale Paoli, son of Giacinto Paoli.

The Republic of Genoa continued its slow decline well into the 18th century, losing its last Mediterranean colony, the island fortress of Tabarka, to the Bey of Tunis in 1742.[43]

The Convention of Turin of 1742, in which Austria allied with the Kingdom of Sardinia, caused some consternation in the Republic. Consequently, the Republic of Genoa signed a secret treaty with the Bourbon allies of Kingdom of France, Spanish Empire and Kingdom of Naples. On 26 June 1745, the Republic of Genoa declared war on the Kingdom of Sardinia. This decision would prove disastrous for Genoa, which later surrendered to the Austrians in September 1746 and was briefly occupied before a revolt liberated the city two months later.[44]

The Republic of Genoa, in a weak state and not capable of suppressing the Corsican struggle for independence, was forced to cede Corsica to France in the 1768 Treaty of Versailles. Only a year later, Napoleon Bonaparte was born in Corsica.

In 1780, the Confetteria Romanengo was founded in Genoa.[45]

The fall of the Republic

[edit]

The direct invasion of Napoleon (during the Campaigns of 1796) and his representatives in Genoa was the final act that led to the fall of the Republic in early June, who overthrew the old elites which had ruled the state for all of its history, giving birth to the Ligurian Republic on 14 June 1797, under the military occupation of Napoleonic France.

19th century

[edit]During the Siege of Genoa (1800), 30,000 of Genoa's 160,000 inhabitants had died of starvation and disease. After Bonaparte's seizure of power in France, a more conservative constitution was enacted, but the Ligurian Republic's life was short—in 1805 it was annexed by France, becoming the départements of Apennins, Gênes, and Montenotte.[46]

The annexation to the Kingdom of Sardinia

[edit]

Following the fall of Napoleon, Genoa regained ephemeral independence, with the name of the Repubblica genovese, which lasted less than a year. However, the Congress of Vienna established the annexation of the whole territories of the former Genoese Republic to the Kingdom of Sardinia, governed by the House of Savoy, contravening the principle of restoring the legitimate governments and monarchies of the old Republic.[47]

Italian Risorgimento

[edit]

In the 19th century, Genoa consolidated its role as a major seaport and an important steel and shipbuilding centre. In Genoa in 1853, Giovanni Ansaldo founded Gio. Ansaldo & C. whose shipyards would build some of the most beautiful ships in the world, such as ARA Garibaldi, SS Roma, MS Augustus, SS Rex, SS Andrea Doria, SS Cristoforo Colombo, MS Gripsholm, SS Leonardo da Vinci, SS Michelangelo, and SS SeaBreeze. In 1854, the ferry company Costa Crociere was founded. In 1861 the Registro Italiano Navale Italian register of shipping was created, and in 1879 the Yacht Club Italiano. The owner Raffaele Rubattino in 1881 was among the founders of the ferry company Navigazione Generale Italiana which then become the Italian Line.[49] In 1870 Banca di Genova was founded which in 1895 changed its name to Credito Italiano and in 1998 became Unicredit. In 1874 the city was completely connected by railway lines to France and the rest of Italy: Genoa-Turin, Genoa-Ventimiglia, Genoa-Pisa. In 1884 Rinaldo Piaggio founded Piaggio & C. that produced locomotives and railway carriages and then in 1923 began aircraft production. In 1888 the Banca Passadore was established. In 1898 the insurance company called Alleanza Assicurazioni was founded.

20th century

[edit]

In 1917 Lloyd Italico insurance company was founded. From 1935 to 1940 Torre Piacentini was built in Genoa. It was one of the first skyscrapers built in Europe and, until 1954, the tallest habitable building in Italy. In 1956 Genoa took part in the Regatta of the Historical Marine Republics. In 1962 Genoa International Boat Show was established. In 1966 Euroflora was established.[50] In 1970 Genoa was hit by a serious flood, which caused the Bisagno stream to overflow. In 1987 the Banco di San Giorgio was established. In 1992 Genoa celebrated the Colombiadi[51] or Genoa Expo '92, the celebration of the 500th anniversary of the discovery of the American Continent by Christopher Columbus. The area of the ancient port of Genoa is restructured and expanded also with the works of the architect Renzo Piano.

21st century

[edit]

In 2001, Genoa hosted the 27th G8 summit. It was overshadowed by violent anti-globalisation protests, with one protester killed.[52] In 2003, the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia (IIT) was established. In 2004, the European Union designated Genoa as the European Capital of Culture for that year, along with the French city of Lille. In 2015, work began to secure the Genoa area, hit by the floods of 2010, 2011 and 2014, with the reconstruction and expansion of the coverage of the Bisagno stream.[53] Work also began on the completion of the underground stream channel of the Ferreggiano river, which flooded several times in various floods, including the most tragic one in 1970.[54] In 2017, the architect Renzo Piano donated the design of the Levante Waterfront[55][56] to the Municipality of Genoa; this project involves a radical transformation of the Fiera di Genova, with the creation of a new dock and an urban park, the continuation of Corso Italia toward Porta Siberia and the construction of residential structures. In 2018, the first planning and study works began for the realization of the Waterfront of Levante project.[57] From 21 April to 6 May 2018, Euroflora 2018 took place, an exhibition of flowers and ornamental plants for the first time in the Parchi di Nervi venue rather than the historic venue of the Fiera di Genova. On 14 August 2018 the Ponte Morandi viaduct bridge for motor vehicles collapsed during a torrential downpour, leading to 43 deaths.[58] The bridge's remains were demolished in August 2019. The replacement bridge, the Genoa-Saint George Bridge, was inaugurated in August 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The tragedy of the collapse of the Morandi Bridge and its rapid reconstruction with a new viaduct designed by Renzo Piano, which occurred during the pandemic, facilitated by a redefinition of the implementing rules of public procurement, which has been defined as the Genoa model,[59][60] is expected to hasten the construction of the Levante Waterfront and other important work in the city.

In 2021, Genoa Mayor Marco Bucci and President of Liguria Giovanni Toti launched a new plan for the modernization and redevelopment of the entirety of Genoa, which has as its fulcrum Renzo Piano's Levante Waterfront project.[61] From 23 April 2022 to 8 May 2022, Euroflora 2022 took place for the second time at the Nervi Parks.[62] In 2023 Genoa was the finish of The Ocean Race.[63] In 2024 Genoa was the 2024 European Capital of Sport.[64][65] On March 7, 2024, Mayor Bucci presented the vision of Genoa 2030, a development and urban renewal plan for Genoa to be completed in 2030.[66][67][68]

Flag

[edit]

The flag of Genoa is a St. George's Cross, a red cross on a white field.

Genoa's patron saint was Saint Lawrence until at least 958, but the Genoese transferred their allegiance to Saint George (and Saint John the Baptist) at some point during the 11th or 12th century, most likely with the rising popularity of the military saint during the Crusades. Genoa also had a banner displaying a cross since at latest 1218, possibly as early as 1113.[69] But the cross banner was not associated with the saint; indeed, the saint had his own flag, the vexillum beati Georgii (first mentioned in 1198), a red flag showing George and the dragon. A depiction of this flag is shown in the Genoese annals under the year 1227. The Genoese flag with the red cross was used alongside this "Saint George's flag", from at least 1218, known as the insignia cruxata comunis Janue ("cross ensign of the commune of Genoa").

The saint's flag was the city's main war flag, but the cross flag was used alongside it in the 1240s.[70]

The Saint George's flag (i.e. the flag depicting the saint) remained the main flag of Genoa at least until the 1280s. The flag now known as the "St. George's Cross" seems to have replaced it as Genoa's main flag at some point during the 14th century. The Book of Knowledge of All Kingdoms (c. 1385) shows it, inscribed with the word iustiçia, and described as:

And the lord of this place has as his ensign a white pennant with a red cross. At the top it is inscribed with 'justice', in this manner.[71]

There was also a historiographical tradition claiming[72] that the flag of England derives from the Genoese flag, which derives from the Knights Templar's red cross, during the Third Crusade in 1190, but it cannot be substantiated as historical.[73]

Geography

[edit]The city of Genoa covers an area of 243 square kilometres (94 sq mi) between the Ligurian Sea and the Apennine Mountains. It stretches along the coast for about 30 kilometres (19 mi) from the neighbourhood of Voltri to Nervi, and for 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from the coast to the north along the valleys Polcevera and Bisagno. The territory of Genoa is popularly divided into 5 main zones: the centre, the west, the east, the Polcevera and the Bisagno Valley. Although much of the city centre is at a low elevation, the territory surrounding it is mountainous, with undeveloped land usually in steep terrain.

Genoa is adjacent to two popular Ligurian vacation spots: Camogli and Portofino. In the metropolitan area of Genoa lies Aveto Natural Regional Park.

Climate

[edit]Genoa has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa), that is bordering closely on a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfa), with plentiful precipitation due to its location on a common storm track. Due to its position between the sea and mountains over 1000 meters high, each neighborhood of Genoa has specific climatic characteristics.

The average yearly temperature is around 20 °C (68 °F) during the day and 14 °C (57 °F) at night. In the coldest months, the average temperature is 12 °C (54 °F) during the day and 6 °C (43 °F) at night. In the warmest months – July and August – the average temperature is 28 °C (82 °F) during the day and 22 °C (72 °F) at night. The daily temperature range is limited, with an average range of about 6 °C (11 °F) between high and low temperatures. Genoa also sees significant moderation from the sea, in stark contrast to areas behind the Ligurian mountains such as Parma, where summers are hotter and winters are quite cold.

Annually, the average 2.9 of nights recorded temperatures of ≤0 °C (32 °F) (mainly in January). The coldest temperature ever recorded was −8 °C (18 °F) in February 2012; the highest temperature ever recorded during the day is 38.5 °C (101 °F) in August 2015. Average annual number of days with temperatures of ≥30 °C (86 °F) is about 8, four days in July and August.[74]

Average annual temperature of the sea is 17.5 °C (64 °F), from 13 °C (55 °F) in the period January–March to 25 °C (77 °F) in August. In the period from June to October, the average sea temperature exceeds 19 °C (66 °F).[75]

Genoa is also a windy city, especially during winter when northern winds often bring cool air from the Po Valley (usually accompanied by lower temperatures, high pressure and clear skies). Another typical wind blows from southeast, mostly as a consequence of Atlantic disturbances and storms, bringing humid and warmer air from the sea. Snowfall is sporadic, but does occur almost every year, albeit big amounts in the city centre are rare.[76][77] Genoa often receives heavy rainfall in autumn from strong convection. Even so, the overall number of precipitation days is quite modest. There are on average 11.57 days annually with thunder, which is more common from May to October than other times of the year.[78]

Annual average relative humidity is 68%, ranging from 63% in February to 73% in May.[74]

Sunshine hours total above 2,200 per year, from an average 4 hours of sunshine duration per day in winter to average 9 hours in summer.

| Climate data for Genoa (1991–2020 normals), 2 m asl, sunshine 1971–2000, extremes since 1955 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.3 (68.5) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

29.4 (84.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

35.4 (95.7) |

38.3 (100.9) |

34.2 (93.6) |

28.9 (84.0) |

22.9 (73.2) |

20.8 (69.4) |

38.3 (100.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 12.1 (53.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.5 (70.7) |

24.9 (76.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

13.1 (55.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.4 (65.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.1 (77.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

13.3 (55.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.5 (50.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −8.5 (16.7) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.6 (43.9) |

7.3 (45.1) |

13.9 (57.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

9.0 (48.2) |

5.1 (41.2) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 76.4 (3.01) |

57.9 (2.28) |

73.8 (2.91) |

83.6 (3.29) |

57.8 (2.28) |

51.2 (2.02) |

26.2 (1.03) |

47.6 (1.87) |

115.9 (4.56) |

149.7 (5.89) |

200.2 (7.88) |

99.4 (3.91) |

1,039.7 (40.93) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 5.9 | 5.0 | 5.3 | 7.0 | 5.8 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 5.5 | 7.4 | 8.8 | 6.9 | 68.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75.4 | 73.2 | 71.2 | 72.7 | 75.7 | 76.5 | 75.2 | 75.0 | 75.6 | 80.0 | 79.5 | 76.6 | 75.6 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

5.1 (41.2) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

18.7 (65.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 117.8 | 130.5 | 158.1 | 192.0 | 220.1 | 246.0 | 294.5 | 266.6 | 201.0 | 173.6 | 111.0 | 111.6 | 2,222.8 |

| Source 1: Météo Climat[79] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Servizio Meteorologico,[74] data of sunshine hours,[80] NOAA (Dew point for Sestri[78]), Weather.Directory (humidity)[81] | |||||||||||||

Government

[edit]Municipal government

[edit]The Municipal Council of Genoa is currently led by a center-left coalition headed by Silvia Salis as mayor. She was elected in May 2025.

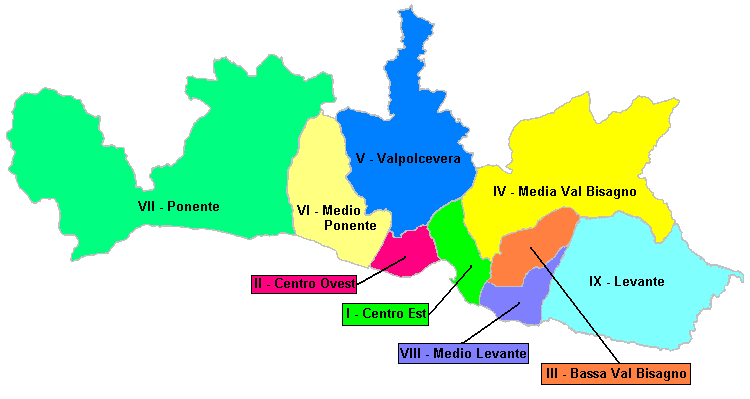

Administrative subdivision

[edit]The city of Genoa is subdivided into nine municipi (administrative districts), as approved by the Municipal Council in 2007.[82]

| Municipio | Population (% of total) | Quartieri |

|---|---|---|

| Centro-Est | 91,402 (15.0%) | Prè, Molo, Maddalena, Oregina, Lagaccio, San Nicola, Castelletto, Manin, San Vincenzo, Carignano, Portoria |

| Centro-Ovest | 66,626 (10.9%) | Sampierdarena, Belvedere, Campasso, San Bartolomeo, San Teodoro, Angeli |

| Bassa Val Bisagno | 78,791 (12.9%) | San Fruttuoso, Sant'Agata, Marassi, Quezzi, Fereggiano, Forte Quezzi |

| Media Val Bisagno | 58,742 (9.6%) | Staglieno (Parenzo, San Pantaleo), Molassana, Sant'Eusebio, Montesignano, Struppa (Doria, Prato) |

| Valpolcevera | 62,492 (10.3%) | Rivarolo, Borzoli Est, Certosa, Teglia, Begato, Bolzaneto, Morego, San Quirico, Pontedecimo |

| Medio Ponente | 61,810 (10.1%) | Sestri, Borzoli Ovest, San Giovanni Battista, Cornigliano, Campi, Calcinara, |

| Ponente | 63,027 (10.3%) | Voltri, Crevari, Pra', Palmaro, Ca' Nuova, Pegli, Multedo, Castelluccio |

| Medio Levante | 61,759 (10.1%) | Foce, Brignole, San Martino, Chiappeto, Albaro, San Giuliano, Lido, Puggia |

| Levante | 66,155 (10.8%) | Sturla, Quarto, Quartara, Castagna, Quinto al Mare, Nervi, Apparizione, Borgoratti, San Desiderio, Bavari, Sant'Ilario |

Cityscape

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2025) |

Main sights

[edit]

Notable to the city are the Palazzi dei Rolli, included in UNESCO World Heritage Site Genoa: Le Strade Nuove and the system of the Palazzi dei Rolli. The world-famous Strade Nuove are via Garibaldi (Strada Nuova), via Cairoli (Strada Nuovissima) and via Balbi (Strada Balbi). Among the most important palaces are the Palazzo Rosso, Palazzo Bianco, Palazzo Podestà o di Nicolosio Lomellino, Palazzo Reale, Palazzo Angelo Giovanni Spinola, Palazzo Pietro Spinola di San Luca and Palazzo Spinola di Pellicceria.

Genoa's historic centre is articulated in a maze of squares and narrow caruggi (typical Genoese alleys). It joins a medieval dimension with following 16th century and Baroque interventions (the ancient Via Aurea, now Via Garibaldi).

Near Via Garibaldi, through the public elevator Castelletto Levante, one can reach one of the most scenic places in the city, Belvedere Castelletto. The centre of Genoa is connected to its upper part by ancient paths caught between tall palaces, called creuze. Walking along these small paths one can reach magnificent places like the Santuario di Nostra Signora di Loreto. Very beautiful is the upper ring road so-called Circonvallazione a Monte that includes Corso Firenze, Corso Paganini, Corso Magenta, Via Solferino, and Corso Armellini.

San Lorenzo cathedral has a splendid portal and the dome designed by Galeazzo Alessi. Inside is found the treasure of the Cathedral where among other objects there is also what is said to be the Holy Chalice.

The symbols of the city are the Lanterna (the lighthouse) (117 metres (384 feet) high), old and standing lighthouse visible in the distance from the sea (beyond 30 kilometres (19 miles)), and the monumental fountain of Piazza De Ferrari, recently restored, out-and-out core of the city's life. Near Piazza De Ferrari and Teatro Carlo Felice is the Mazzini Gallery, a typical nineteenth-century structure with many elegant shops and coffee bars.

Another tourist destination is the ancient seaside district of Boccadasse (which means "the mouth of the donkey"), with its multicolour boats, set as a seal to Corso Italia, the promenade which runs along the Lido d'Albaro, and known for its ice-creams. After Boccadasse you can continue along the sea up to Sturla.

Just out of the city centre, but still part of the 33 km (21 mi) of coast included in the municipality's territory, are Nervi, natural doorway to the Ligurian East Riviera, and Pegli, the point of access to the West Riviera. Nervi offers many attractions: the promenade overlooking the sea called Passeggiata Anita Garibaldi; parks covered with lush tropical vegetation; numerous villas and palaces open to the public that now house museums (like GAM-Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Raccolte Frugone Museum, Museo Giannettino Luxoro and Wolfsoniana). (see also Parchi di Nervi) The East Riviera of Genoa called Riviera di Levante is part of the Italian Riviera. East Riviera is full of interesting towns to visit, and then from Genoa to east are: Bogliasco, Pieve Ligure, Sori, Recco, Camogli, Portofino, Santa Margherita Ligure, Rapallo, Zoagli, Chiavari, Lavagna and Sestri Levante. In the west, Pegli is the site of the famous Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini and Arenzano is a seaside town at the foot of the Parco naturale regionale del Beigua.

The new Genoa based its rebirth upon the restoration of the green areas of the immediate inland parts, among them the Parco naturale regionale del Beigua, and upon the construction of facilities such as the Aquarium of Genoa in the Old Harbour – the biggest in Italy and one of the major in Europe – and its Marina (the tourist small port which holds hundreds of pleasure boats). All of these are inside the restored Expo Area, arranged in occasion of the Columbian Celebrations of 1992.

Near the city are Camogli and San Fruttuoso abbey accessible by a daily ferry from the Old Harbour (Porto Antico) of Genoa. In the seabed in front of the San Fruttuoso abbey there is the Christ of the Abyss. From the Old Harbour one can reach by boat other famous seaside places around Genoa such as Portofino or a little more distant, Lerici and the Cinque Terre.

The regained pride gave back to the city the consciousness of being capable of looking to the future without forgetting its past. The resumption of several flourishing hand-crafting activities, far-back absent from the caruggi of the old town, is a direct evidence of it. The restoration of many of Genoa's churches and palaces in the 1980s and the 1990s contributed to the city's rebirth. A notable example the Renaissance, Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta, sitting on the top of the hill of Carignano and visible from almost every part of the city. The total restoration of Doge's Palace and of the Old Harbour, and the rebuilding of Teatro Carlo Felice, destroyed by bombing in the Second World War, were two more points of strength for the realisation of a new Genoa.

From the 1960s onward, Genoa could not avoid a significant urban renewal, which, as in many other major cities, involved building large public housing complexes. The quality, utility, and functionality of these developments have been, and remain, controversial among the residents who live there.[clarification needed] The most well-known case is that of the so-called "Biscione", a development in the shape of a long snake, situated on the hills of the populous district of Marassi, and one of the group of houses known as "Le Lavatrici" (the washing machines), in the district of Prà.

Beyond a complete restyling of the area, the ancient port zone nearby the Mandraccio opening, in Porta Siberia, was enriched by Genoese architect Renzo Piano with a large sphere made of metal and glass, installed in the port's waters, not far from the Aquarium of Genoa, and unveiled in 2001 in occasion of the G8 Summit held in Genoa. The sphere (called by the citizens "Piano's bubble" or "The Ball"), after hosting an exposition of fens from Genoa's Botanical Gardens, currently houses the reconstruction of a tropical environment, with several plants, little animals and butterflies. Piano also designed the subway stations and, in the hills area, the construction – in collaboration with UNESCO – of Punta Nave, base of the Renzo Piano Building Workshop.

Nearby the Old Harbour is the so-called "Matitone", a skyscraper in shape of a pencil, that lays side by side with the group of the WTC towers, core of the San Benigno development, today base of part of the Municipality's administration and of several companies.

Churches

[edit]

St. Lawrence Cathedral (Cattedrale di San Lorenzo) is the city's cathedral, built in a Gothic-Romanesque style. Other notable historical churches are the Commandery of the Saint John's Order called Commenda di San Giovanni di Prèl, San Matteo, San Donato, Santa Maria di Castello, Sant'Agostino (deconsecrated since the 19th century, sometimes is used for theatrical representations), Santo Stefano, Santi Vittore e Carlo, Basilica della Santissima Annunziata del Vastato, San Pietro in Banchi, Santa Maria delle Vigne, Nostra Signora della Consolazione, San Siro, Santa Maria Maddalena, Santa Maria Assunta di Carignano, Sant'Anna and Chiesa del Gesù e dei Santi Ambrogio e Andrea. San Bartolomeo degli Armeni houses the Image of Edessa and San Pancrazio after the World War II was entrusted to the ligurian delegation of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. These churches and basilicas are built in Romanesque (San Donato, Santa Maria di Castello, Commenda di San Giovanni di Pré), Gothic (San Matteo, Santo Stefano, Sant'Agostino), Baroque (San Siro) or Renaissance (Santa Maria Assunta di Carignano, San Pietro in Banchi) appearance, or a mix of different styles (Nostra Signora della Consolazione, Santissima Annunziata del Vastato; this last has a Baroque interior and a Neoclassicist façade).

Another well known Genoese church is the shrine of Saint Francis of Paola, notable for the outer courtyard overlooking the port and the memorial to all those who died at sea. This church is of artistic mention in that the tile depictions of the Via Crucis Stations along the brick path to the church.

Near Genoa is found the Shrine of Nostra Signora della Guardia, (the sanctuary is said to have inspired the writer Umberto Eco in making his novel The Name of the Rose). Another interesting church in the neighborhoods of Genoa is San Siro di Struppa.

The city was the birthplace of several popes (Innocent IV, Adrian V, Innocent VIII, and Benedict XV) and various saints (Syrus of Genoa, Romulus of Genoa, Catherine of Genoa, and Virginia Centurione Bracelli). The Archbishop of Genoa Jacobus de Voragine wrote the Golden Legend. Also from Genoa were: Giovanni Paolo Oliva, the Superior General of the Society of Jesus; Girolamo Grimaldi-Cavalleroni, the Archbishop of Aix; Ausonio Franchi, priest, philosopher, and theologian; Cardinal Giuseppe Siri; and the priests Francesco Repetto, Giuseppe Dossetti, Gianni Baget Bozzo, and Andrea Gallo. The present archbishop of Genoa, Cardinal Angelo Bagnasco, comes from a Genoese family but was born in Pontevico, near Brescia (see also Archdiocese of Genoa).

Buildings and palaces

[edit]

The main features of central Genoa include the Piazza De Ferrari, around which are the Opera and the Palace of the Doges. Nearby, just outside the medieval city walls, is located Christopher Columbus House where Christopher Columbus is said to have lived as a child, although the current building is an 18th-century reconstruction of the original which was destroyed by the French naval bombing of 1684.

In the old port area called Porto Antico, is located Palazzo di San Giorgio. In the Middle Ages, this palace was the headquarters of the Bank of Saint George. In its prisons, Marco Polo and Rustichello da Pisa composed The Travels of Marco Polo.

Strada Nuova (now Via Garibaldi), in the old city, alongside Via Cairoli and via Balbi, was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2006. This district was designed in the mid-16th century to accommodate Mannerist palaces built by the city's most eminent families.

Of the many palaces built by the nobility in the city center of Genoa, 114 have not been substantially altered (see also Rolli di Genova): among these, 42 Palazzi dei Rolli are inscribed on the World Heritage List.[83] The most famous are Palazzo Rosso, Palazzo Bianco, Palazzo Doria Tursi, Palazzo Gerolamo Grimaldi, Palazzo Podestà, Palazzo Reale, Palazzo Angelo Giovanni Spinola, Palazzo Pietro Spinola di San Luca, Palazzo Spinola di Pellicceria, Palazzo Cicala. Palazzo Bianco, Palazzo Rosso and Palazzo Doria Tursi are also known as Musei di Strada Nuova and host the renowned art collection bequeathed to the city by the Genoese filantropist Maria Brignole Sale De Ferrari, Duchess of Galliera, as well as the violins of the Genoese violinist Niccolò Paganini.[84] The Flemish artist and diplomat Peter Paul Rubens wrote Palazzi di Genova in 1622, a book with his own depiction of the palaces of Genoa in the 17th century.[85]

The Genoese Renaissance began with the construction of Villa del Principe commissioned by Andrea Doria: the architects were Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli and Giovanni Ponzello, the interior was painted by Perino del Vaga and the garden fountain was realised by Taddeo Carlone.[86]

In 1548 Galeazzo Alessi, with the project of Villa Giustiniani-Cambiaso, designed a new prototype of Genoese palace that would be an inspiration to other architects working in Genoa as Bartolomeo Bianco, Pietro Antonio Corradi, Rocco Lurago, Giovan Battista Castello, and Bernardino Cantone.

Scattered around the city are many villas, built between the fifteenth and the twentieth centuries. Among the best known are: Villa Brignole Sale Duchessa di Galliera, Villa Durazzo-Pallavicini, Villa Doria Centurione, Villa Durazzo Bombrini, Villa Serra, Villa Giustiniani-Cambiaso, Villa Rossi Martini, Villa Imperiale Scassi, Villa Grimaldi, Villa Negrone Moro, Villa Rosazza, Villetta Di Negro, Villa delle Peschiere, Villa Imperiale, Villa Saluzzo Bombrini, and Villa Grimaldi Fassio.

As it regards the 19th century remember the architects Ignazio Gardella (senior), and Carlo Barabino which among other things, realises together with Giovanni Battista Resasco, the Monumental Cemetery of Staglieno. The cemetery is renowned for its statues and sepulchral monuments that preserve the mortal remains of notable personalities, including Giuseppe Mazzini, Fabrizio De André, and Constance Lloyd (Oscar Wilde's wife). In the first half of the 19th century they are completed the Albergo dei Poveri and the Acquedotto storico. In 1901 Giovanni Antonio Porcheddu realised the Silos Granari.

The city is rich in testimony of the Gothic Revival like Albertis Castle, Castello Bruzzo, Villa Canali Gaslini and Mackenzie Castle designed by the architect Gino Coppedè. Genoa is also rich of Art Nouveau works, among which: Palazzo della Borsa (Genova), Via XX Settembre (Gino Coppedè, Gaetano Orzali and others), Hotel Bristol Palace, Grand Hotel Miramare and Stazione marittima. Works of Rationalist architecture of the first half of the 20th century are Torre Piacentini and Piazza della Vittoria where Arco della Vittoria, both designed by the architect Marcello Piacentini. Other architects who have changed the face of Genoa in the 20th century are: Ignazio Gardella, Luigi Carlo Daneri who realised the Piazza Rossetti and the residential complex so-called Il Biscione, Mario Labò, Aldo Rossi, Ludovico Quaroni, Franco Albini who designed the interiors of Palazzo Rosso, and Piero Gambacciani. The Edoardo Chiossone Museum of Oriental Art, designed by Mario Labò, has one of the largest collections of Oriental art in Europe.

Other notable architectural works include: the Old Harbour's new design with the Aquarium, the Bigo and the Biosfera by Renzo Piano, the Palasport di Genova, the Matitone skyscraper, and the Padiglione B of Genoa Fair, by Jean Nouvel. Genoa was home to the Ponte Morandi by Riccardo Morandi, built in 1967, collapsed in 2018 and demolished February–June 2019.[87]

Old Harbour

[edit]

The Old Harbour ("Porto Antico" in Italian) is the ancient part of the port of Genoa. The harbour gave access to outside communities creating a good geographical situation for the city.[46] The city is spread out geographically along a section of the Liguria coast, which makes trading by ship possible. Before the development of car, train, and airplane travel, the main outside access for the city was the sea, as the surrounding mountains made trade north by land more difficult than coastal trade. Trade routes have always connected Genoa on an international scale, with increasingly farther reach starting from trade along Europe's coastline before the medieval period to today's connection across continents.[88] In its heyday the Genoese Navy was a prominent power in the Mediterranean.

As the Genoa harbour was so important to the merchants for their own economic success, other nearby harbours and ports were seen as competition for a landing point for foreign traders. In the 16th century, the Genovese worked to destroy the local shipping competition, the Savona harbour.[46] Taking matters into their own hands, the Genoa merchants and the politically powerful in Genoa attacked the harbour of Savona with stones.[46] This action was taken to preserve the economic stability and wealth of the city during the rise in prominence of Savona. The Genovese would go as far as to war with other coastal, trading cities such as Venice,[46] to protect the trade industry.

Renzo Piano redeveloped the area for public access, restoring the historical buildings (like the Cotton warehouses) and creating new landmarks like the Aquarium, the Bigo and recently the "Bolla" (the Sphere). The main touristic attractions of this area are the famous Aquarium and the Museum of the Sea (MuMA). In 2007 these attracted almost 1.7 million visitors.[89]

Walls and fortresses

[edit]

The city of Genoa during its long history at least since the ninth century had been protected by different lines of defensive walls. Large portions of these walls remain today, and Genoa has more and longer walls than any other city in Italy. The main city walls are known as "Ninth century walls", "Barbarossa Walls" (12th century), "Fourteenth century walls", "Sixteenth century walls" and "New Walls" ("Mura Nuove" in Italian). The more imposing walls, built in the first half of the 17th century on the ridge of hills around the city, have a length of almost 20 km (12 mi). Some fortresses stand along the perimeter of the "New Walls" or close them.

Parks

[edit]

Genoa has 82,000 square metres (880,000 square feet) of public parks in the city centre, such as Villetta Di Negro which is right in the heart of the town, overlooking the historical centre. Many bigger green spaces are situated outside the centre: in the east are the Parks of Nervi (96,000 square metres or 1,030,000 square feet) overlooking the sea, in the west the beautiful gardens of Villa Durazzo Pallavicini and its Giardino botanico Clelia Durazzo Grimaldi (265,000 square metres or 2,850,000 square feet). The numerous villas and palaces of the city also have their own gardens, like Palazzo del Principe, Villa Doria, Palazzo Bianco and Palazzo Tursi, Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellino, Albertis Castle, Villa Rosazza, Villa Croce, Villa Imperiale Cattaneo, Villa Bombrini, Villa Brignole Sale Duchessa di Galliera, Villa Serra and many more.[90]

The city is surrounded by natural parks such as Parco naturale regionale dell'Antola, Parco naturale regionale del Beigua, Aveto Natural Regional Park and the Ligurian Sea Cetacean Sanctuary (a marine protected area).

Aquarium of Genoa

[edit]The Aquarium of Genoa (in Italian: Acquario di Genova) is the largest aquarium in Italy and among the largest in Europe. Built for Genoa Expo '92, it is an educational, scientific and cultural centre. Its mission is to educate and raise public awareness as regards conservation, management and responsible use of aquatic environments. It welcomes over 1.2 million visitors a year.

Control of the entire environment, including the temperature, filtration and lighting of the tanks was provided by local Automation Supplier Orsi Automazione, acquired in 2001 by Siemens. The Aquarium of Genoa is co-ordinating the AquaRing EU project. It also provides scientific expertise and a great deal of content for AquaRing, including documents, images, academic content and interactive online courses, via its Online Resource Centre.[91]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1115 | 50,000 | — |

| 1300 | 100,000 | +100.0% |

| 1400 | 100,000 | +0.0% |

| 1400+ | 117,000 | +17.0% |

| 1861 | 242,447 | +107.2% |

| 1871 | 256,486 | +5.8% |

| 1881 | 289,234 | +12.8% |

| 1901 | 377,610 | +30.6% |

| 1911 | 465,496 | +23.3% |

| 1921 | 541,562 | +16.3% |

| 1931 | 590,736 | +9.1% |

| 1936 | 634,646 | +7.4% |

| 1951 | 688,447 | +8.5% |

| 1961 | 784,194 | +13.9% |

| 1971 | 816,872 | +4.2% |

| 1981 | 762,895 | −6.6% |

| 1991 | 678,771 | −11.0% |

| 2001 | 610,307 | −10.1% |

| 2011 | 586,180 | −4.0% |

| 2021 | 561,203 | −4.3% |

| Source: ISTAT[92][93],[94][95][96] | ||

As of 2025, there are 563,947 people residing in Genoa, of whom 48.1% were male and 51.9% were female.[97] The city is characterised by rapid aging and a long history of demographic decline that has shown a partial slowdown in the last decade.[98] Genoa has the lowest birth rate and is the most aged of any large Italian city. Minors (children ages 18 and younger) totalled only 14.12% of the population compared to pensioners who number 26.67%. This compares with the Italian average of 18.06% (minors) and 19.94% (pensioners). The median age of Genoa's residents is 47, compared to the Italian average of 42. The current birth rate of the city is only 7.49 births per 1,000 inhabitants, compared to the national average of 9.45.

Economy

[edit]The Genoa metropolitan area had a GDP amounting to $30.1 billion in 2011, or $33,003 per capita.[99]

Ligurian agriculture has increased its specialisation pattern in high-quality products (flowers, wine, olive oil) and has thus managed to maintain the gross value-added per worker at a level much higher than the national average (the difference was about 42% in 1999).[100] The value of flower production represents over 75% of the agriculture sector turnover, followed by animal farming (11.2%) and vegetable growing (6.4%).

Steel, once a major industry during the booming 1950s and 1960s, phased out after the late 1980s crisis, as Italy moved away from the heavy industry to pursue more technologically advanced and less polluting productions. So the Ligurian industry has turned towards a widely diversified range of high-quality and high-tech products (food, shipbuilding (in Sestri Ponente and in metropolitan area – Sestri Levante), electrical engineering and electronics, petrochemicals, aerospace etc.). Nonetheless, the regions still maintain a flourishing shipbuilding sector (yacht construction and maintenance, cruise-liner building, military shipyards).[100]

In the services sector, the gross value-added per worker in Liguria is 4% above the national average. This is due to the increasing diffusion of modern technologies, particularly in commerce and tourism. A good motorway network (376 km (234 mi) in 2000) makes communications with the border regions relatively easy. The main motorway is located along the coastline, connecting the main ports of Nice (in France), Savona, Genoa and La Spezia. The number of passenger cars per 1000 inhabitants (524 in 2001) is below the national average (584). On average, about 17 million tonnes of cargo are shipped from the main ports of the region and about 57 million tonnes enter the region.[100] The Port of Genoa, with a trade volume of 58.6 million tonnes,[101] ranks first in Italy,[102] second in terms of twenty-foot equivalent units after the transshipment port of Gioia Tauro, with a trade volume of over 2 million TEUs.[103] The main destinations for the cargo-passenger traffic are Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Barcelona, and the Canary Islands.

Some big companies based in Genoa include Ansaldo STS, Ansaldo Energia, Erg, Piaggio Aerospace, Registro Italiano Navale, Banca Carige, SLAM, and Costa Cruises.

Education

[edit]

The first organised forms of higher education in Genoa date back to the 13th century when private colleges were entitled to award degrees in medicine, philosophy, Theology, Law, Arts.[104] Today the University of Genoa, founded in the 15th century, is one of the largest in Italy, with 11 faculties, 51 departments and 14 libraries. In 2007–2008, the university had 41,000 students and 6,540 graduates.[105]

Genoa is also home to other Colleges, Academies or Museums:

- The University of Genoa

- The CNR Area della Ricerca di Genova

- The Accademia ligustica di belle arti

- The Accademia Ligure di scienze e lettere

- The Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia

- The ISICT-istituto superiore di studi in tecnologie dell'informazione e della comunicazione

- The Renzo Piano Building Workshop

- The OBR Open Building Research

- The Accademia Italiana della Marina Mercantile

- The "Niccolò Paganini" Conservatory

- The Italian Hydrographic Institute

- The Deledda International School

- The Deutsche Schule Genua

- The Genoa Comics Academy

- The International School in Genoa

- The Russian Ballet College

The Italian Institute of Technology was established in 2003 jointly by the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities and Research and the Italian Minister of Economy and Finance, to promote excellence in basic and applied research. The main fields of research of the Institute are Neuroscience, Robotics, Nanotechnology, Drug discovery. The central research labs and headquarters are located in Morego, in the neighbourhood of Bolzaneto.[106]

Clemson University, based in South Carolina, United States, has a villa in Genoa where architecture students and students in related fields can attend for a semester or year-long study program.

Florida International University (FIU), based in Miami, Florida, United States, also has a small campus in Genoa, with the University of Genoa which offers classes within the FIU School of Architecture.

Science

[edit]

Genoa is the birthplace of Giovanni Battista Baliani and Vincentio Reinieri, of the geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, of the Nobel Prize astrophysicist Riccardo Giacconi and of the astronaut Franco Malerba. The city is home to the Erzelli Hi-Tech Park, to the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, to the Istituto idrografico della Marina and annually hosts the Festival della Scienza. The city has an important tradition in the fields of the geology, paleontology, botany and naturalistic studies, among the most eminent personalities we remember: Lorenzo Pareto, Luigi d'Albertis, Enrico Alberto d'Albertis, Giacomo Doria and Arturo Issel, we point the Orto Botanico dell'Università di Genova. Very important and renowned is the Istituto Giannina Gaslini.

In 1846 the city hosted the eighth Meeting of Italian Scientists and in 1902 Luigi Carnera discovered an asteroid and called it "485 Genua", dedicating it to the Latin name of Genoa.

Erzelli science technology park

[edit]

The western area of Genoa hosts the Erzelli GREAT Campus, an under-construction science technology park which houses the high-tech corporations Siemens, Ericsson, Esaote, and robotics laboratories of the Italian Institute of Technology (IIT).[107] The Erzelli GREAT Campus science park is undergoing a process of enlargement, and in the future will host the new Faculty of Engineering of University of Genoa. The project has been struggling in recent years with enterprises laying off their employees and no real growth.[108][109]

Transport

[edit]Ports

[edit]

Several cruise and ferry lines serve the passenger terminals in the old port, with a traffic of 3.2 million passengers in 2007.[110] MSC Cruises chose Genoa as one of its main home ports, in competition with the Genoese company Costa Cruises, which moved its home port to Savona. The quays of the passenger terminals extend over an area of 250,000 square metres (2,700,000 square feet), with 5 equipped berths for cruise vessels and 13 for ferries, for an annual capacity of 4 million ferry passengers, 1.5 million cars and 250,000 trucks.[111]

The historical maritime station of Ponte dei Mille is today a technologically advanced cruise terminal, with facilities designed after the world's most modern airports, to ensure fast embarking and disembarking of all latest generation ships carrying a thousand passengers. A third cruise terminal is currently under construction in the redesigned area of Ponte Parodi, once a quay used for grain traffic.

The Costa Concordia cruise ship, owned by Costa Cruises, was docked at the port before being dismantled.[112]

Air transport

[edit]

The Airport of Genoa (IATA: GOA, ICAO: LIMJ) (Italian: Aeroporto di Genova) also named Christopher Columbus Airport (Italian: Aeroporto Cristoforo Colombo) is built on an artificial peninsula, 4 NM (7.4 km; 4.6 mi) west[113] of the city. The airport is currently operated by Aeroporto di Genova S.P.A., which has recently upgraded the airport complex that now connects Genoa with several daily flights to Rome, Naples, Paris, London, Madrid and Munich. In 2008, 1,202,168 passengers travelled through the airport,[114] with an increase of international destinations and charter flights.

Public transport

[edit]

The main railway stations are Genoa Brignole in the east and Genoa Principe in the west. Genoa Brignole is close to the business districts and the exhibition centre, while the Principe is close to the port, the university and the historical centre. From these two stations depart the main trains connecting Genoa to France, Turin, Milan and Rome.

Genoa's third most important station is Genoa Sampierdarena, which serves the densely populated neighbourhood of Sampierdarena. 23 other local stations serve the other neighbourhoods on the 30-kilometre-long coast line from Nervi to Voltri and on the northern line through Bolzaneto and the Polcevera Valley.

The municipal administration of Genoa plans to transform these urban railway lines to be part of the rapid transit system, which now consists of the Metropolitana di Genova (Genoa Metro), a light metro connecting Brin to the city centre. The metro line was extended to Brignole Station in December 2012. Trains currently pass through Corvetto station between De Ferrari and Brignole without stopping. A possible further extension towards the eastern densely populated boroughs was planned, but the municipal administration intends to improve the public transport by investing in new tram lines instead of completing the extension of the light metro.[115] The current stations of the metro line are Brin-Certosa, Dinegro, Principe, Darsena, San Giorgio, Sant'Agostino and De Ferrari; the line is 5.3 km (3.3 mi) long.

The city's hilly nature has influenced its public transport. The city is served by two funicular railways (the Zecca–Righi funicular, the Sant'Anna funicular), the Quezzi inclined elevator, the Principe–Granarolo rack railway, and ten public lifts.[116]

The city's metro, bus and trolleybus network is operated by AMT (Azienda Mobilità e Trasporti S.p.A.). The Drin Bus is a demand responsive transport service that connects the hilly, low-density areas of Genoa.[117][118][119] The average time people spend commuting on public transit in Genova, for example to and from work, is 54 minutes on a weekday. 10% of public transit riders ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 12 minutes, while 13% of riders wait over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 4 km, while 2% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[120]

Culture

[edit]Visual arts

[edit]

Genoese painters active in the 14th century include Barnaba da Modena and his local followers Nicolò da Voltri and at the same time, the sculptor Giovanni Pisano reached Genoa to make the monument for Margaret of Brabant, whose remains are today housed in the Museum of Sant'Agostino.

In the 16th century along with the flourishing trade between the Republic of Genoa and Flanders also grew the cultural exchanges. The painters Lucas and Cornelis de Wael lived in Genoa for a long time, where they played the role of a magnet for many Flemish painters like Jaan Roos, Giacomo Legi, Jan Matsys, Andries van Eertvelt and Vincent Malo.

This creative environment also attracted the two most important Flemish painters, Rubens and Van Dyck, who along with Bernardo Strozzi.[121] gave life to the Genoese Painting School of the 17th century.

Much of the city's art is found in its churches and palaces, where there are numerous Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo frescos. They are rich in works of art the Cathedral, the Chiesa del Gesù e dei Santi Ambrogio e Andrea where The Circumcision and the "Miracles of St. Ignatius" by Rubens, the Assunzione della Vergine by Guido Reni. The Church of San Donato contains works of Barnaba da Modena, Nicolò da Voltri and Joos van Cleve,[121] the Church of Santo Stefano The Stoning of St. Stephen by Giulio Romano and the Church of Santa Maria Assunta the sculptures by Filippo Parodi and Pierre Puget, very interesting is the Santa Maria di Castello. But most of the works are kept in the Palaces like Palazzo Bianco where "Ecce Homo" by Caravaggio, "Susannah and the Elders" by Veronese, and the Garden Party in Albaro by Magnasco are kept; Palazzo Rosso with the Portrait of Anton Giulio Brignole-Sale by van Dyck; Cleopatra morente by Guercino and works of Dürer; Bernardo Strozzi; Mattia Preti; Veronese; Palazzo Spinola di Pellicceria where the "Portrait of Giovanni Carlo Doria on Horseback" by Rubens and Ecce Homo by Antonello da Messina (see also the series of Ecce Homo by Antonello da Messina) are kept; Palazzo Tursi with the Penitent Magdalene by Canova; and Palazzo Reale which contains works of Strozzi, Gaulli, Tintoretto, van Dyck, Simon Vouet, and Guercino.

The most important Genoese painters are: Luca Cambiaso; Bernardo and Valerio Castello; Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione; Domenico and Paolo Gerolamo Piola; Gregorio De Ferrari; Bernardo Strozzi; Giovanni Battista Gaulli and Alessandro Magnasco. Sculptors include Filippo Parodi, the wood sculptor Anton Maria Maragliano, Francesco Maria Schiaffino and Agostino Carlini who was member of the Royal Academy.

The famous humanist author, architect, poet and philosopher Leon Battista Alberti was born in Genoa on 14 February 1404. Simonetta Vespucci, considered the most beautiful woman of her time, was also born in Genoa. She is portrayed in The Birth of Venus and Primavera by Sandro Botticelli and in Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci by Piero di Cosimo.

Genoa is also famous for its numerous tapestries which decorated the city's many salons. Whilst the patrician palaces and villas in the city were and still are austere and majestic, the interiors tended to be luxurious and elaborate, often full of tapestries, many of which were Flemish.[121] Famous is the Genoese lace called with its name of Turkish origin macramè. Very used in Genoa is the cobblestone called Risseu and a kind of azulejo called laggioni.

Genoa has been likened by many to a Mediterranean New York, perhaps for its high houses that in the Middle Ages were the equivalent of today's skyscrapers, perhaps for the sea route Genoa-New York which in past centuries has been travelled by millions of emigrants. The architect Renzo Picasso in his visionary designs reinforces this strange affinity between the two cities.

In the Monumental Cemetery of Staglieno, you can admire some magnificent sculpture of the 19th century and early 20th century like Monteverde Angel by Giulio Monteverde, or works by artists such as Augusto Rivalta, Leonardo Bistolfi, Edoardo Alfieri, Santo Varni.

Amongst the most notable Genoese painters of the 19th century and of the first half of the 20th century are Tammar Luxoro, Ernesto Rayper, Rubaldo Merello, and Antonio Giuseppe Santagata. The sculptor Francesco Messina also grew up in Genoa.

In 1967 the Genoese historian, critic and curator Germano Celant coined the term Arte Povera. Enrico Accatino was another important art theorist and Emanuele Luzzati was the production designer and illustrator like Lorenzo Mongiardino, also a production designer and architect. Two other important artists are Emilio Scanavino and Vanessa Beecroft.

The yearly International Cartoonists Exhibition was founded in 1972 in Rapallo, near Genoa. A notable figure is the illustrator and comics artist Giovan Battista Carpi.

Literature

[edit]

"Anonymous of Genoa" was one of the first authors in Liguria and Italy who wrote verses in the Vernacular. It explained that in Genoa Marco Polo and Rustichello da Pisa, in the prisons of Palazzo San Giorgio, wrote The Travels of Marco Polo. The Golden Legend is a collection of hagiographies written by the Archbishop of Genoa Jacobus de Voragine. To animate the Genoese literary environment of the 16th century were Gabriello Chiabrera and Ansaldo Cebà, the latter best known for his correspondence with Sara Copia Sullam. The city has been the birthplace of the historian Caffaro di Rustico da Caschifellone; of the poet "Martin Piaggio"; of the famous historian, philosopher and journalist Giuseppe Mazzini; of the writer Piero Jahier; of the poet Nobel Prize Eugenio Montale. The writer and translator Fernanda Pivano, the journalist "Vito Elio Petrucci" and the poet Edoardo Sanguineti, the literary critic Carlo Bo instead was born in Sestri Levante near Genoa. We have also remember the dialet poet Edoardo Firpo, the dialect "poeta crepuscolare" Giambattista Vigo, and the symbolist Ceccardo Roccatagliata Ceccardi.

The city of Genoa has been an inspiration to many writers and poets among whom: Dino Campana, Camillo Sbarbaro, Gaspare Invrea who wrote "The mouth of the wolf" and Giorgio Caproni. Between the alleys of the historical centre there is the Old Libreria Bozzi. The "Berio Civic Library" houses the precious manuscript entitled "The Durazzo Book of Hours". In the first half of the 20th century, the Mazzini Gallery's was a meeting place of many artists, writers and intellectuals among whom Guido Gozzano, Salvatore Quasimodo, Camillo Sbarbaro, Francesco Messina, Pierangelo Baratono, Eugenio Montale. In the 1930s the Circoli magazine was active in Genoa, and after World War II the "Il Gallo" magazine. Coveted and known from the 1960s to the 1980s was the Genoese literary lounge animated by the writer Minnie Alzona. Dutch writer Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer wrote "La Superba", a novel in which Genoa is prominently featured. This was followed by the autobiographical novel "Brieven uit Genua".

Since 1995, every June in Genoa the Genoa International Poetry Festival takes place, conceived by Claudio Pozzani with the help of Massimo Bacigalupo.

Music

[edit]

Genoa was a centre of Occitan culture in Italy and for this reason it developed an important school of troubadours: Lanfranc Cigala, Jacme Grils, Bonifaci Calvo, Luchetto Gattilusio, Guillelma de Rosers, and Simon Doria.

Genoa is the birthplace of the composer Simone Molinaro, violinist and composer Niccolò Paganini, violinist Camillo Sivori and composer Cesare Pugni. In addition, the famous violin maker Paolo de Barbieri. Paganini's violin, Il Cannone Guarnerius, is kept in Palazzo Tursi. The city is the site of the Niccolò Paganini Music Conservatory which was originally established as the Scuola Gratuita di Canto in 1829.[122]

Alessandro Stradella, a composer of the middle baroque, lived in Genoa and was assassinated in 1682.

Felice Romani was a poet who wrote many librettos for the opera composers like Gaetano Donizetti and Vincenzo Bellini. Giovanni Ruffini was another poet known for writing the libretto of the opera Don Pasquale for its composer.

In 1847, Goffredo Mameli and Michele Novaro composed "Il Canto degli Italiani".

In 1857, debuted the work of Giuseppe Verdi entitled Simon Boccanegra inspired by the first Doge of Genoa, Simone Boccanegra.

Genoa is also the birthplace of the condcuctor Fabio Luisi and of many opera singers like Giuseppe Taddei, Margherita Carosio, Luciana Serra, Ottavio Garaventa, Luisa Maragliano and Daniela Dessì.

The oldest theatre in Genoa was the Teatro del Falcone. Active since the 16th century, it was the second public theatre in Italy, only preceded by the one in the Republic of Venice.[123] It was followed by the Teatro delle Vigne which, however, along with other important theaters in the city (Teatro Margherita, Teatro Paganini, Teatro Colombo), was demolished between the 19th and 20th centuries, either to make way for urban expansion or due to damage caused by bombing of Genoa during World War II.

The Teatro Carlo Felice, the main opera theatre in the city, was built in 1828 in the Piazza De Ferrari, and named for the monarch of the then Kingdom of Sardinia (which included the present regions of Sardinia, Piedmont and Liguria). The theatre was the centre of music and social life in the 19th century. On various occasions in the history of the theatre, presentations have been conducted by Mascagni, Richard Strauss, Hindemith and Stravinsky. Other prominent Genoese theaters are the Teatro Nazionale di Genoa, Politeama Genovese, Teatro di Sant'Agostino and Teatro Gustavo Modena.

On the occasion of the Christopher Columbus celebration in 1992, new musical life was given to the area around the old port, including the restoration of the house of Paganini and presentations of the trallalero, the traditional singing of Genoese dock workers.

The trallalero, traditional music in the Genoese dialect, is a polyphonic vocal music, performed by five men and several songs. The trallalero are ancient songs that have their roots in the Mediterranean tradition. Another aspect of the traditional Genoese music is the "Nostalgic Song". The principal authors and singers of the Nostalgic Song in Genoese dialect are Mario Cappello who wrote the piece "Ma se ghe penso" (English: "But if I think about it"), a memory of Genoa by an emigrant to Argentina, Giuseppe Marzari, Agostino Dodero up to I Trilli, Piero Parodi, Buby Senarega, Franca Lai. The traditional Nostalgic Song will have a great influence on the so-called Scuola Genovese (Genoese School) of singer-songwriters that in some cases will mix the nostalgic feeling with pop and jazz atmospheres.

The singer Natalino Otto started the swing genre in Italy and his friend and colleague Pippo Barzizza was a composer, arranger, conductor and music director. Other musicians, composers and arrangers are Angelo Francesco Lavagnino, Gian Piero Reverberi, Gian Franco Reverberi, Oscar Prudente, Pivio and Aldo De Scalzi.

Genoa in the second half of the 20th century was famous for an important school of Italian singer-songwriters, so-called Scuola Genovese, that includes Umberto Bindi, Luigi Tenco", "Gino Paoli", "Bruno Lauzi", "Fabrizio de André, Ivano Fossati, Angelo Branduardi" and Francesco Baccini. Nino Ferrer was also born in Genoa. In the 70s there were formed in Genoa numerous bands of Italian progressive rock like New Trolls, Picchio dal Pozzo, Latte e Miele, and Delirium. Today we point the band Buio Pesto and The Banshee band.

Some songs about the city of Genoa are part of Italian popular culture, like "Via del Campo" and "La Città Vecchia", both by Fabrizio de André, "Genova per noi" by Paolo Conte, "La Casa in Via del Campo" the song also sung by Amalia Rodrigues and "Piazza Alimonda" the song about the facts of Genoa 2001 by Francesco Guccini.

Fabrizio de André in 1984 released the album Crêuza de mä, totally written in Genoese dialect.

I Madrigalisti di Genova is a vocal and instrumental group formed in 1958 which specialised in medieval and Renaissance repertoire.

The city has numerous music festivals, among which are Concerts at San Fruttuoso abbey, Premio Paganini, I Concerti di San Torpete, International Music Festival Genova, We Love Jazz, Gezmatz Festival & Workshop, and Goa-Boa Festival. In the town of Santa Margherita Ligure the ancient abbey of Cervara is often the site of chamber music.

Giovine Orchestra Genovese, one of the oldest concert societies in Italy, was founded in Genoa in 1912.

Cinema

[edit]Genoa has been the set for many films and especially for the genre called Polizieschi. Notable directors born in Genoa include Pietro Germi and Giuliano Montaldo, the actors: Gilberto Govi, Vittorio Gassman, Paolo Villaggio, Alberto Lupo, the actresses: Lina Volonghi, Delia Boccardo, Rosanna Schiaffino, Eleonora Rossi Drago, Marcella Michelangeli and the pornographic actress Moana Pozzi. Before actor Bartolomeo Pagano's cinema career, he was a camallo, which means stevedore, at the port of Genoa. His cinema career began with the film Cabiria, one of the first and most famous kolossal. In 1985 were filmed in Genoa some scenes of Pirates by Roman Polanski, finished shooting they left in the Old Harbour the galleon Neptune.

Some films set in Genoa:

- Agata and the Storm

- Amore che vieni, amore che vai, from the novel Un destino ridicolo

- Attention! Bandits!

- Behind Closed Shutters

- The Blue-Eyed Bandit

- Carlo Giuliani, Boy

- The Case of the Bloody Iris

- The Conspiracy in Genoa

- Days and Clouds

- Di che segno sei?

- Diaz - Don't Clean Up This Blood

- Father and Son

- General Della Rovere

- Genoese Dragnet

- Genova

- High Crime

- In the Beginning There Was Underwear

- The Magistrate

- Mad Sea

- Mark Shoots First

- Mean Frank and Crazy Tony

- Merciless Man

- The Mouth of the Wolf

- Onde

- The Police Serve the Citizens?

- Scent of a Woman

- Street Law

- Stregati

- The Walls of Malapaga

- The Yellow Rolls-Royce

Language

[edit]The Genoese dialect (Zeneize) is the most important dialect of the Ligurian language, and is commonly spoken in Genoa alongside Italian. Ligurian is listed by Ethnologue as a language in its own right, of the Romance branch, the Ligurian Romance language, and not to be confused with the ancient Ligurian language. Like the languages of Lombardy, Piedmont, and surrounding regions, it is of Gallo-Italic derivation.

Sports

[edit]

There are two major football teams in Genoa: Genoa C.F.C. and U.C. Sampdoria; the former is the oldest football club operating in Italy (see History of Genoa C.F.C.). The football section of the club was founded in 1893 by James Richardson Spensley, an English doctor. Genoa 1893 has won 9 championships (between 1898 and 1924) and 1 Coppa Italia (1936–37). U.C. Sampdoria was founded in 1946 from the merger of two existing clubs, Andrea Doria (founded in 1895) and Sampierdarenese (founded in 1911). Sampdoria has won one Italian championship (1990–91 Serie A), 4 Coppa Italia, 1 UEFA Cup Winners' Cup (1989–90) and 1 Supercoppa Italiana. Both Genoa C.F.C. and U.C. Sampdoria play their home games in the Luigi Ferraris Stadium, which holds 36,536 spectators. Deeply felt is the derby called Derby della Lanterna.

The international tennis tournament AON Open Challenger takes place in Genoa.

In rugby union the city is represented by CUS Genova Rugby, which is the rugby union team of the University of Genoa Sports Centre. CUS Genova had their peak in 1971–1973 when the team was runner-up of the Italian Serie A for three consecutive seasons and contested unsuccessfully the title to Petrarca Rugby. Amongst the CUS Genova players who represented Italy at international level the most relevant were Marco Bollesan and Agostino Puppo.

In 1947 was founded the CUS Genova Hockey and in 1968 the basketball club Athletic Genova. The city hosted the FIFA World Cup in 1934 and 1990, in 1988 the European Karate Championships and in 1992 the European Athletics Indoor Championships. In 2003 the indoor sporting arena, Vaillant Palace, was inaugurated.

The city lends its name to a particular type of a sailing boat so-called Genoa sail, in 2007 the city hosts the Tall Ships' Races.

Cuisine

[edit]This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (September 2017) |

Popular sauces of Genoese cuisine include Pesto sauce, garlic sauce called Agliata, "Walnut Sauce" called Salsa di noci, Green sauce, Pesto di fave, Pasta d'acciughe and the meat sauce called tócco,[124] not to be confused with the Genovese sauce, that in spite of the name is typical of the Neapolitan cuisine. The Genoese tradition includes many varieties of pasta as Trenette, Corzetti, Trofie, Pansoti, gnocchi and also: Farinata, Panissa and Cuculli.

Key ingredient of Genoese cuisine is the Prescinsêua used among other things to prepare the Savory spinach pie and the Barbagiuai and still Focaccia con le cipolle, Farinata di ceci, Focaccette al formaggio and the Focaccia con il formaggio which means "Focaccia with cheese" that is even being considered for European Union PGI status. Other key ingredients are many varieties of fish as Sardines, Anchovies (see also Acciughe ripiene and Acciughe sotto sale), Garfish, Swordfish, Tuna, Octopus, Squid, Mussels, the Stoccafisso which means Stockfish (see also Brandacujun), the Musciame and Gianchetti.

Other elements of Genoese cuisine include the Ligurian Olive Oil, the cheeses like Brös, U Cabanin, San Stè cheese, Giuncata, the sausages like Testa in cassetta, Salame cotto and Genoa salami. Fresh pasta (usually trofie, trenette) and "gnocchi" with pesto sauce are probably the most iconic among Genoese dishes. Pesto sauce is prepared with fresh Genovese basil, pine nuts, grated parmesan and pecorino mixed, garlic and olive oil pounded together.[125] Liguria wine such as Pigato, Riviera Ligure di Ponente Vermentino, Sciacchetrà, Rossese di Dolceacqua and Ciliegiolo del Tigullio are popular. Dishes of Genoese tradition include the Tripe cooked in various recipes like Sbira, the Polpettone di melanzane, the Tomaxelle, the Minestrone alla genovese,[126] the Bagnun, the fish-consisting Ciuppin (the precursor to San Francisco's Cioppino), the Buridda, the Seppie in zimino and the Preboggion.

Two sophisticated recipes of Genoese cuisine are: the Cappon magro and the Cima alla genovese (a song by Fabrizio De André is titled 'A Çimma and is dedicated to this Genoese recipe). Originating in Genoa is Pandolce that gave rise to Genoa cake. The city lands its name to a special paste used to prepare cakes and pastries called Genoise and to the Pain de Gênes.

In Genoa there are many food markets in typical nineteenth-century iron structures as Mercato del Ferro, Mercato Dinegro, Mercato di Via Prè, Mercato di piazza Sarzano, Mercato del Carmine, Mercato della Foce, Mercato Romagnosi. The Mercato Orientale instead is in masonry and has a circular structure.

People

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2018) |

Genoa has left an extraordinary impression on many noted personalities. Friedrich Nietzsche loved Genoa and wrote some of his works there. Sigmund Freud and Ezra Pound lived near Genoa in Rapallo. Anton Chekhov said that Genoa "is the most beautiful city in the world," and Richard Wagner wrote: "I have never seen anything like this Genoa! it is something indescribably beautiful".