Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Optical rectenna

View on Wikipedia

An optical rectenna is a rectenna (rectifying antenna) that works with visible or infrared light.[1] A rectenna is a circuit containing an antenna and a diode, which turns electromagnetic waves into direct current electricity. While rectennas have long been used for radio waves or microwaves, an optical rectenna would operate the same way but with infrared or visible light, turning it into electricity.

While traditional (radio- and microwave) rectennas are fundamentally similar to optical rectennas, it is vastly more challenging in practice to make an optical rectenna. One challenge is that light has such a high frequency—hundreds of terahertz for visible light—that only a few types of specialized diodes can switch quickly enough to rectify it. Another challenge is that antennas tend to be a similar size to a wavelength, so a very tiny optical antenna requires a challenging nanotechnology fabrication process. A third challenge is that, being very small, an optical antenna typically absorbs very little power, and therefore tend to produce a tiny voltage in the diode, which leads to low diode nonlinearity and hence low efficiency. Due to these and other challenges, optical rectennas have so far been restricted to laboratory demonstrations, typically with intense focused laser light producing a tiny but measurable amount of power.

Nevertheless, it is hoped that arrays of optical rectennas could eventually be an efficient means of converting sunlight into electric power, producing solar power more efficiently than conventional solar cells. The idea was first proposed by Robert L. Bailey in 1972.[2] As of 2012, only a few optical rectenna devices have been built, demonstrating only that energy conversion is possible.[3] It is unknown if they will ever be as cost-effective or efficient as conventional photovoltaic cells.

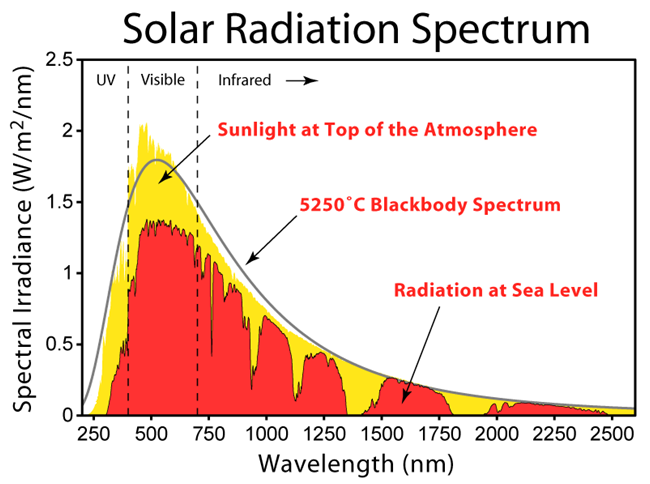

The term nantenna (nano-antenna) is sometimes used to refer to either an optical rectenna, or an optical antenna by itself. [4] In 2008 it was reported that Idaho National Laboratories designed an optical antenna to absorb wavelengths in the range of 3–15 μm.[5] These wavelengths correspond to photon energies of 0.4 eV down to 0.08 eV. Based on antenna theory, an optical antenna can absorb any wavelength of light efficiently provided that the size of the antenna is optimized for that specific wavelength. Ideally, antennas would be used to absorb light at wavelengths between 0.4 and 1.6 μm because these wavelengths have higher energy than far-infrared (longer wavelengths) and make up about 85% of the solar radiation spectrum[6] (see Figure 1).

History

[edit]Robert Bailey, along with James C. Fletcher, received a patent (US 3760257) in 1973 for an "electromagnetic wave energy converter". The patented device was similar to modern day optical rectennas. The patent discusses the use of a diode "type described by [Ali Javan] in the IEEE Spectrum, October, 1971, page 91", to whit, a 100 nm-diameter metal cat's whisker to a metal surface covered with a thin oxide layer. Javan was reported as having rectified 58 THz infrared light. In 1974, T. Gustafson and coauthors demonstrated that these types of devices could rectify even visible light to DC current[7] Alvin M. Marks received a patent in 1984 for a device explicitly stating the use of sub-micron antennas for the direct conversion of light power to electrical power.[8] Marks's device showed substantial improvements in efficiency over Bailey's device.[9] In 1996, Guang H. Lin reported resonant light absorption by a fabricated nanostructure and rectification of light with frequencies in the visible range.[9] In 2002, ITN Energy Systems, Inc. published a report on their work on optical antennas coupled with high frequency diodes. ITN set out to build an optical rectenna array with single digit efficiency. Although they were unsuccessful, the issues associated with building a high efficiency optical rectenna were better understood.[6]

In 2015, Baratunde A. Cola's research team at the Georgia Institute of Technology, developed a solar energy collector that can convert optical light to DC current, an optical rectenna using carbon nanotubes,.[10] Vertical arrays of multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) grown on a metal-coated substrates were coated with insulating aluminum oxide and altogether capped with a metal electrode layer. The small dimensions of the nanotubes act as antennae, capable of capturing optical wavelengths. The MWCNT also doubles as one layer of a metal-insulator-metal (MIM) tunneling diode. Due to the small diameter of MWCNT tips, this combination forms a diode that is capable of rectifying the high frequency optical radiation. The overall achieved conversion efficiency of this device is around 10−5 %.[10] Nonetheless, optical rectenna research is ongoing.

The primary drawback of these carbon nanotube rectenna devices is a lack of air stability. The device structure originally reported by Cola used calcium as a semitransparent top electrode because the low work function of calcium (2.9 eV) relative to MWCNTs (~5 eV) creates the diode asymmetry needed for optical rectification. However, metallic calcium is highly unstable in air and oxidizes rapidly. Measurements had to be made within a glovebox under an inert environment to prevent device breakdown. This limited practical application of the devices.

Cola and his team later solved the challenges with device instability by modifying the diode structure with multiple layers of oxide. In 2018 they reported the first air-stable optical rectenna along with efficiency improvements.

The air-stability of this new generation of rectenna was achieved by tailoring the diode's quantum tunneling barrier. Instead of a single dielectric insulator, they showed that the use of multiple dissimilar oxide layers enhances diode performance by modifying diode tunneling barrier. By using oxides with different electron affinities, the electron tunneling can be engineered to produce an asymmetric diode response regardless of the work function of the two electrodes. By using layers of Al2O3 and HfO2, a double-insulator diode (metal-insulator-insulator-metal (MIIM)) was constructed that improved the diode's asymmetric response more than 10-fold without the need for low work function calcium, and the top metal was subsequently replaced with air-stable silver.

Future efforts will be focused on improving the device efficiency by investigating alternative materials, manipulating the MWCNTs and the insulating layers to encourage conduction at the interface, and reduce resistances within the structure.

Another approach was presented in 2022 by Proietti Zaccaria Remo and collaborators at the Italian Institute of Technology, based on a top-down solution where the antenna and the rectifier were merged together in a single plasmonic-based solution.[11] The proposed rectenna was tested at 1064 nm, both in single and matrix format, achieving an efficiency of 10−3 %. Furthermore, both experimental and theoretical analyses were conducted at 780 nm, with positive results suggesting that plasmonic-based rectennas could potentially serve as a viable approach for achieving a high-performing rectenna in the visible range. Although this solution represents a significant step forward, several challenges remain that prevent optical rectennas from reaching the 1% efficiency threshold required for practical applications. Key obstacles include achieving optical resonance regardless of the incident radiation conditions (e.g., angle of incidence) and improving the rectifier performance.

Theory

[edit]The theory behind optical rectennas is essentially the same as for traditional (radio or microwave) antennas. Incident light on the antenna causes electrons in the antenna to move back and forth at the same frequency as the incoming light. This is caused by the oscillating electric field of the incoming electromagnetic wave. The movement of electrons is an alternating current (AC) in the antenna circuit. To convert this into direct current (DC), the AC must be rectified, which is typically done with a diode. The resulting DC current can then be used to power an external load. The resonant frequency of antennas (frequency which results in lowest impedance and thus highest efficiency) scales linearly with the physical dimensions of the antenna according to simple microwave antenna theory.[6] The wavelengths in the solar spectrum range from approximately 0.3-2.0 μm.[6] Thus, in order for a rectifying antenna to be an efficient electromagnetic collector in the solar spectrum, it needs to be on the order of hundreds of nm in size.

Because of simplifications used in typical rectifying antenna theory, there are several complications that arise when discussing optical rectennas. At frequencies above infrared, almost all of the current is carried near the surface of the wire which reduces the effective cross sectional area of the wire, leading to an increase in resistance. This effect is also known as the "skin effect". From a purely device perspective, the I-V characteristics would appear to no longer be ohmic, even though Ohm's law, in its generalized vector form, is still valid.

Another complication of scaling down is that diodes used in larger scale rectennas cannot operate at THz frequencies without large loss in power.[5] The large loss in power is a result of the junction capacitance (also known as parasitic capacitance) found in p-n junction diodes and Schottky diodes, which can only operate effectively at frequencies less than 5 THz.[6] The ideal wavelengths of 0.4–1.6 μm correspond to frequencies of approximately 190–750 THz, which is much larger than the capabilities of typical diodes. Therefore, alternative diodes need to be used for efficient power conversion. In current optical rectenna devices, metal-insulator-metal (MIM) tunneling diodes are used. Unlike Schottky diodes, MIM diodes are not affected by parasitic capacitances because they work on the basis of electron tunneling. Because of this, MIM diodes have been shown to operate effectively at frequencies around 150 THz.[6]

Advantages

[edit]This section may contain original research. (September 2011) |

One of the biggest claimed advantages of optical rectennas is their high theoretical efficiency. When compared to the theoretical efficiency of single junction solar cells (30%), optical rectennas appear to have a significant advantage. However, the two efficiencies are calculated using different assumptions. The assumptions involved in the rectenna calculation are based on the application of the Carnot efficiency of solar collectors. The Carnot efficiency, η, is given by

where Tcold is the temperature of the cooler body and Thot is the temperature of the warmer body. In order for there to be an efficient energy conversion, the temperature difference between the two bodies must be significant. R. L. Bailey claims that rectennas are not limited by Carnot efficiency, whereas photovoltaics are. However, he does not provide any argument for this claim. Furthermore, when the same assumptions used to obtain the 85% theoretical efficiency for rectennas are applied to single junction solar cells, the theoretical efficiency of single junction solar cells is also greater than 85%.

The most apparent advantage optical rectennas have over semiconductor photovoltaics is that rectenna arrays can be designed to absorb any frequency of light. The resonant frequency of an optical antenna can be selected by varying its length. This is an advantage over semiconductor photovoltaics, because in order to absorb different wavelengths of light, different band gaps are needed. In order to vary the band gap, the semiconductor must be alloyed or a different semiconductor must be used altogether.[5]

Limitations and disadvantages

[edit]This section may contain original research. (September 2011) |

As previously stated, one of the major limitations of optical rectennas is the frequency at which they operate. The high frequency of light in the ideal range of wavelengths makes the use of typical Schottky diodes impractical. Although MIM diodes show promising features for use in optical rectennas, more advances are necessary to operate efficiently at higher frequencies.[12]

Another disadvantage is that current optical rectennas are produced using electron beam (e-beam) lithography. This process is slow and relatively expensive because parallel processing is not possible with e-beam lithography. Typically, e-beam lithography is used only for research purposes when extremely fine resolutions are needed for minimum feature size (typically, on the order of nanometers). However, photolithographic techniques have advanced to where it is possible to have minimum feature sizes on the order of tens of nanometers, making it possible to produce rectennas by means of photolithography.[12]

Production

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2011) |

After the proof of concept was completed, laboratory-scale silicon wafers were fabricated using standard semiconductor integrated circuit fabrication techniques. E-beam lithography was used to fabricate the arrays of loop antenna metallic structures. The optical antenna consists of three main parts: the ground plane, the optical resonance cavity, and the antenna. The antenna absorbs the electromagnetic wave, the ground plane acts to reflect the light back towards the antenna, and the optical resonance cavity bends and concentrates the light back towards the antenna via the ground plane.[5] This work did not include production of the diode.

Lithography method

[edit]Idaho National Labs used the following steps to fabricate their optical antenna arrays. A metallic ground plane was deposited on a bare silicon wafer, followed by a sputter deposited amorphous silicon layer. The depth of the deposited layer was about a quarter of a wavelength. A thin manganese film along with a gold frequency selective surface (to filter wanted frequency) was deposited to act as the antenna. Resist was applied and patterned via electron beam lithography. The gold film was selectively etched and the resist was removed.

Roll-to-roll manufacturing

[edit]In moving up to a greater production scale, laboratory processing steps such as the use of electron beam lithography are slow and expensive. Therefore, a roll-to-roll manufacturing method was devised using a new manufacturing technique based on a master pattern. This master pattern mechanically stamps the precision pattern onto an inexpensive flexible substrate and thereby creates the metallic loop elements seen in the laboratory processing steps. The master template fabricated by Idaho National Laboratories consists of approximately 10 billion antenna elements on an 8-inch round silicon wafer. Using this semi-automated process, Idaho National Labs has produced a number of 4-inch square coupons. These coupons. These coupons – of the material science, not commercial variety – were combined to form a broad flexible sheet of antenna arrays. This work did not include production of the diode component.

Atomic layer deposition

[edit]Researchers at the University of Connecticut are using a technique called selective area atomic layer deposition that is capable of producing them reliably and at industrial scales.[13] Research is ongoing to tune them to the optimal frequencies for visible and infrared light.

Economics of optical antennas

[edit]Optical antennas (by itself, omitting the crucial diode and other components) are cheaper than photovoltaics (if efficiency is ignored). While materials and processing of photovoltaics are expensive (currently the cost for complete photovoltaic modules is in the order of 430 USD / m2 in 2011 and declining.[14]), Steven Novack estimates the current cost of the antenna material itself as around 5 - 11 USD / m2 in 2008.[15] With proper processing techniques and different material selection, he estimates that the overall cost of processing, once properly scaled up, will not cost much more. His prototype was a 30 x 61 cm of plastic, which contained only 0.60 USD of gold in 2008, with the possibility of downgrading to a material such as aluminum, copper, or silver.[16] The prototype used a silicon substrate due to familiar processing techniques, but any substrate could theoretically be used as long as the ground plane material adheres properly.

Future research and goals

[edit]In an interview on National Public Radio's Talk of the Nation, Dr. Novack claimed that optical rectennas could one day be used to power cars, charge cell phones, and even cool homes. Novack claimed the last of these will work by both absorbing the infrared heat available in the room and producing electricity which could be used to further cool the room. (Other scientists have disputed this, saying it would violate the second law of thermodynamics.[17][18])

Improving the diode is an important challenge. There are two challenging requirements: Speed and nonlinearity. First, the diode must have sufficient speed to rectify visible light. Second, unless the incoming light is extremely intense, the diode needs to be extremely nonlinear (much higher forward current than reverse current), in order to avoid "reverse-bias leakage". An assessment for solar energy collection found that, to get high efficiency, the diode would need a (dark) current much lower than 1μA at 1V reverse bias.[19] This assessment assumed (optimistically) that the antenna was a directional antenna array pointing directly at the sun; a rectenna that collects light from the whole sky, like a typical silicon solar cell does, would need the reverse-bias current to be even lower still, by orders of magnitude. (The diode simultaneously needs a high forward-bias current, related to impedance-matching to the antenna.)

There are special diodes for high speed (e.g., the metal-insulator-metal tunnel diodes discussed above), and there are special diodes for high nonlinearity, but it is quite difficult to find a diode that is outstanding in both respects at once.

To improve the efficiency of carbon nanotube-based rectenna:

- Low work function: A large work function (WF) difference between the MWCNT is needed to maximize diode asymmetry, which lowers the turn-on voltage required to induce a photoresponse. The WF of carbon nanotubes is 5 eV and the WF of the calcium top layer is 2.9 eV, giving a total work function difference of 2.1 eV for the MIM diode.

- High transparency: Ideally, the top electrode layers should be transparent to allow incoming light to reach the MWCNT antennae.

- Low electrical resistance: Improving device conductivity increases the rectified power output. But there are other impacts of resistance on device performance. Ideal impedance matching between the antenna and diode enhances rectified power. Lowering structure resistances also increases the diode cutoff frequency, which in turn enhances the effective bandwidth of rectified frequencies of light. The current attempt to use calcium in the top layer results in high resistance due to the calcium oxidizing rapidly.

Researchers currently hope to create a rectifier which can convert around 50% of the antenna's absorption into energy.[15] Another focus of research will be how to properly upscale the process to mass-market production. New materials will need to be chosen and tested that will easily comply with a roll-to-roll manufacturing process. Future goals will be to attempt to manufacture devices on pliable substrates to create flexible solar cells.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Moddel, Garret; Grover, Sachit (2013). Garret Moddel; Sachit Grover (eds.). Rectenna Solar Cells. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-3716-1.

- ^ Corkish, R; M.A Green; T Puzzer (December 2002). "Solar energy collection by antennas". Solar Energy. 73 (6): 395–401. Bibcode:2002SoEn...73..395C. doi:10.1016/S0038-092X(03)00033-1. hdl:1959.4/40066. ISSN 0038-092X. S2CID 122707077.

- ^ "M254 Arts & Engineering/Science Research". www.mat.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Awad, Ehab (21 August 2019). "Nano-plasmonic Bundt Optenna for broadband polarization-insensitive and enhanced infrared detection". Scientific Reports. 9 (1) 12197. Bibcode:2019NatSR...912197A. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-48648-6. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6704059. PMID 31434970.

- ^ a b c d Dale K. Kotter; Steven D. Novack; W. Dennis Slafer; Patrick Pinhero (August 2008). Solar Nantenna Electromagnetic Collectors (PDF). 2nd International Conference on Energy Sustainability. INL/CON-08-13925. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Berland, B. (2009-04-13). "Photovoltaic Technologies Beyond the Horizon: Optical Rectenna Solar Cell" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

- ^ Heiblum, M.; Shihyuan Wang; Whinnery, John R.; Gustafson, T. (March 1978). "Characteristics of integrated MOM junctions at DC and at optical frequencies". IEEE Journal of Quantum Electronics. 14 (3): 159–169. Bibcode:1978IJQE...14..159H. doi:10.1109/JQE.1978.1069765. ISSN 0018-9197. S2CID 21688285.

- ^ "United States Patent: 4445050 - Device for conversion of light power to electric power". uspto.gov. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Lin, Guang H.; Reyimjan Abdu; John O'M. Bockris (1996-07-01). "Investigation of resonance light absorption and rectification by subnanostructures". Journal of Applied Physics. 80 (1): 565–568. Bibcode:1996JAP....80..565L. doi:10.1063/1.362762. ISSN 0021-8979. Archived from the original on 2013-02-23.

- ^ a b Sharma, Asha; Singh, Virendra; Bougher, Thomas L.; Cola, Baratunde A. (2015). "A carbon nanotube optical rectenna". Nature Nanotechnology. 10 (12): 1027–1032. Bibcode:2015NatNa..10.1027S. doi:10.1038/nnano.2015.220. PMID 26414198.

- ^ Mupparapu, Rajeshkumar; Cunha, Joao; Tantussi, Francesco; Jacassi, Andrea; Summerer, Leopold; Patrini, Maddalena; Giugni, Andrea; Maserati, Lorenzo; Alabastri, Alessandro; Garoli, Denis; Proietti Zaccaria, Remo (2022). "High-Frequency Light Rectification by Nanoscale Plasmonic Conical Antenna in Point-Contact-Insulator-Metal Architecture". Advanced Energy Materials. 12 (15): 2013785. Bibcode:2022AdEnM..1203785M. doi:10.1002/aenm.202103785. hdl:11585/881194.

- ^ a b "NANTENNA" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-25. Retrieved 2014-05-25.

- ^ "UConn Professor's Patented Technique Key to New Solar Power Technology". University of Connecticut. 4 February 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ "Solarbuzz PV module pricing". May 2011. Archived from the original on 2013-08-11.

- ^ a b "Nanoheating", Talk of the Nation. National Public Radio. 22 Aug. 2008. Transcript. NPR. 15 Feb. 2009.

- ^ Green, Hank. "Nano-Antennas for Solar, Lighting, and Climate Control Archived 2009-04-22 at the Wayback Machine", Ecogeek. 7 Feb. 2008. 15 Feb. 2009. Interview with Dr. Novack.

- ^ Moddel, Garret (2013). "Will Rectenna Solar Cells be Practical?". In Garret Moddel; Sachit Grover (eds.). Rectenna Solar Cells. Springer New York. pp. 3–24. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3716-1_1. ISBN 978-1-4614-3715-4. Quote: "There has been some discussion in the literature of using infrared rectennas to harvest heat radiated from the earth’s surface. This cannot be accomplished with ambient-temperature solar cells due to the second law of thermodynamics" (page 18)

- ^ S.J. Byrnes; R. Blanchard; F. Capasso (2014). "Harvesting renewable energy from Earth's mid-infrared emissions" (PDF). PNAS. 111 (11): 3927–3932. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.3927B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1402036111. PMC 3964088. PMID 24591604. Quote: "...there have also been occasional suggestions in the literature to use rectennas or other devices to harvest energy from LWIR radiation (20-23). However, these analyses have neglected the thermal fluctuations of the diode, as discussed below and in ref. 12, which leads to the absurd conclusion that a room-temperature device can generate useful power from collecting the ambient radiation from room-temperature objects."

- ^ Rectenna Solar Cells, ed. Moddel and Grover, page 10