Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

ORiNOCO

View on Wikipedia

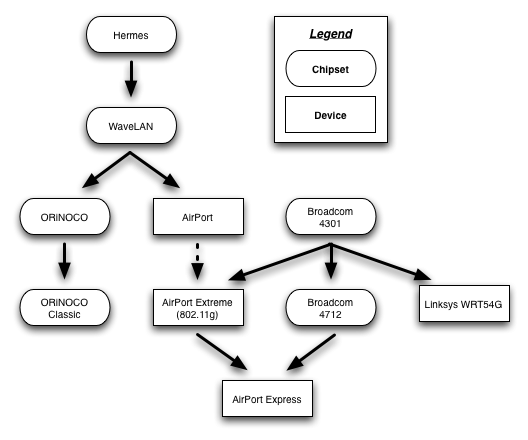

ORiNOCO was the brand name for a family of wireless networking technology by Proxim Wireless (previously Lucent). These integrated circuits (codenamed Hermes) provide wireless connectivity for 802.11-compliant Wireless LANs.

Variants

[edit]

Lucent offered several variants of the PC Card, referred to by different color-based monikers:

- White/Bronze: WaveLAN IEEE Standard 2 Mbit/s PC Cards with 802.11 support.

- Silver: WaveLAN IEEE Turbo 11 Mbit/s PC Cards with 802.11b and 64-bit WEP support.

- Gold: WaveLAN IEEE Turbo 11 Mbit/s PC Cards with 802.11b and 128-bit WEP support.

Later models dropped the 'Turbo' moniker due to 802.11b 11 Mbit/s becoming widespread.

Proxim, after taking over Lucent's wireless division, rebranded all their wireless cards to ORiNOCO - even cards not based on Lucent/Agere's Hermes chipset. Proxim still offers ORiNOCO-based cards under the 'Classic' brand.

Rebranded products

[edit]The WaveLAN chipsets that power ORiNOCO-branded cards were commonly used to power other wireless networking devices, and are compatible with a number of other access points, routers and wireless cards. The following brand and models utilise the chipset, or are rebrands of an ORiNOCO product:

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2007) |

- 3Com AirConnect

- Apple AirPort and AirMac cards (original only, not AirPort Extreme). Modified to remove the antenna stub.

- Avaya World Card

- Cabletron RoamAbout 802.11 DS

- Compaq WL100 11 Mbit/s Wireless Adapter

- Intersil/Conexant Prism II[1]

- D-Link DWL-650

- ELSA AirLancer MC-11

- Enterasys RoamAbout[2]

- Ericsson WLAN Card C11

- Farallon SkyLINE

- Fujitsu RoomWave

- HyperLink Wireless PC Card 11 Mbit/s

- Intel PRO/Wireless 2011

- Lucent Technologies WaveLAN/IEEE Orinoco[1]

- Melco WLI-PCM-L11

- Microsoft Wireless Notebook Adapter MN-520

- NCR WaveLAN/IEEE Adapter

- Proxim LAN PC CARD HARMONY 80211B

- Samsung 11 Mbit/s WLAN Card

- Symbol LA4111 Spectrum24 Wireless LAN PC Card[1]

- Toshiba Wireless LAN Mini PCI Card

Preferred wireless chipset for wardriving

[edit]The ORiNOCO (and their derivatives) is preferred by wardrivers, due to their high sensitivity and the ability to report the level of noise (something that other chips of the era did not report). The pre-Proxim (or 'Classic') ORiNOCO cards have a jack for attaching an external antenna.[4]

Linux drivers

[edit]A Linux Orinoco Driver supported the IEEE 802.11b Hermes/ORiNOCO family of chips. It was included in the Linux kernel from version 2.4.3[5] until its removal in 6.8.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "The Linux orinoco driver". SourceForge. 2013-05-29. Retrieved 2025-03-06.

- ^ "RoamAbout 802.11 Wireless Networking Guide" (PDF).

- ^ "The devices, the drivers - 802.11b". Archived from the original on 2022-08-20. Retrieved 2025-03-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Introduction to NetStumbler".

- ^ Linux ORiNOCO Driver

- ^ LKML: [GIT PULL] Networking for v6.8

External links

[edit]- Official website (proxim.com) at the Wayback Machine (archived 2004-07-20)

- MPL/GPL drivers

ORiNOCO

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Name Origin

The name "Orinoco" originates from the Warao language, spoken by indigenous peoples inhabiting the river's delta region in eastern Venezuela and western Guyana, where it derives from the terms wiri (meaning "where we paddle") and noko (meaning "place"), collectively signifying "a place to paddle" or a navigable waterway suited for canoe travel.[5] This etymology reflects the Warao's deep cultural reliance on the river for transportation and livelihood, as their autonym "Warao" itself translates to "canoe people" or "boat people."[6] The first European sighting of the Orinoco's mouth occurred on August 1, 1498, during Christopher Columbus's third voyage, when he approached the delta's outlets from the Gulf of Paria and mistook the expansive, branching waterways for the entrance to a large gulf or strait separating an island from the mainland.[7] Columbus did not record the indigenous name at the time but instead applied Spanish designations to nearby features, such as naming one of the delta's northern branches "Rio de Gracia" (River of Grace) after anchoring there on August 10, 1498.[8] Over the following centuries, European cartographers and explorers gradually adopted and adapted the indigenous term into forms like "Orynoque" and "Orinoque" (also spelled "Oronoque") in 16th-century Spanish maps and accounts, evolving toward the modern spelling "Orinoco" by the 17th century as the river's full extent became better documented.[9] This linguistic transition preserved the Warao root while integrating it into colonial nomenclature, emphasizing the river's role as a vital navigable artery.Historical and Alternative Names

The Spanish colonial adaptation of the river's name emerged as "Río Orinoco" during early explorations, with the term first documented in accounts of expeditions seeking El Dorado. In 1531, Spanish explorer Diego de Ordaz led the initial recorded voyage up the river from its delta, navigating approximately 1,000 kilometers to the Meta River confluence, where the name "Orinoco" was applied based on indigenous designations encountered along the route.[10] Indigenous groups provided various alternative names reflecting the river's characteristics, such as Paragua, denoting its extensive flooding of surrounding lands.[10] In modern usage, the official name remains Río Orinoco in both Venezuela and Colombia, where it serves as a shared international boundary and waterway. Bilingual contexts occasionally incorporate indigenous terms in cultural or educational materials, such as Warao references in Venezuelan delta communities, though Spanish predominates in official documents and navigation.[1][11]Geography

Physical Course and Dimensions

The Orinoco River measures approximately 2,140 km (1,330 mi) in length, making it one of the longest rivers in South America.[12] It originates in the Sierra Parima mountains within the Guiana Highlands, near the border between Venezuela and Brazil, at an elevation of about 1,000 m above sea level.[3] From this highland source, the river descends with a total elevation drop of roughly 1,000 m over its course, facilitating its flow through diverse terrains to sea level at the Atlantic Ocean.[3] The river's path traces a distinctive arc-shaped trajectory. It initially flows westward from the Sierra Parima through rugged terrain and forested highlands, then veers northward across the expansive Venezuelan Llanos—a vast lowland plain—before curving eastward to reach the Atlantic Ocean via its delta near the island of Trinidad.[1] This meandering route, spanning roughly four unequal segments, encircles the ancient Guiana Shield and reflects the geological influences of the surrounding Precambrian formations.[3] Along its length, the Orinoco exhibits significant variations in width and depth, adapting to the regional topography and seasonal flooding. In the upper reaches, the channel is narrow, typically 1 km wide, confined by the hilly landscapes of the Guiana Highlands. As it progresses into the middle sections through the Llanos, the river broadens dramatically to up to 22 km (14 mi) during high-water periods, allowing for extensive flooding across the plains; depths in these areas can reach 100 m in deeper pools and channels.[13] These physical dimensions underscore the river's role as a dynamic waterway, with its cross-sectional profile influencing navigation and sediment transport throughout much of its extent.[3]Basin and Tributaries

The Orinoco Basin encompasses an area of approximately 880,000 km² (340,000 sq mi), covering about 65–80% of Venezuela's territory and 20–35% of Colombia's, with very small portions in Brazil and Guyana.[14][3] This vast drainage region spans diverse physiographic zones, including the Andean foothills to the west, the expansive Llanos grasslands to the north, and the ancient Guiana Shield to the south, which collectively shape the basin's ecological and hydrological dynamics.[3] Major left-bank tributaries, such as the Ventuari, Caura, and Caroní rivers, originate primarily from the Guiana Shield and drain the southern portions of the basin.[3] These rivers contribute clear or blackwater flows from forested highlands and tepuis, supporting the Orinoco's overall hydrological balance by adding volume from stable, ancient geological formations. The Caroní River, in particular, serves as a key hydropower source, with major dams like the Guri complex harnessing its flow for electricity generation in Venezuela.[15] On the right bank, significant tributaries including the Meta, Apure, and Guaviare rivers flow from the Colombian Andes and the Llanos, delivering sediment-rich whitewater that enhances the basin's nutrient transport and seasonal flooding patterns.[3] These Andean-sourced streams originate in high-elevation cordilleras and traverse lowland savannas, integrating rainfall from tropical montane regions into the Orinoco system. Collectively, the tributaries sustain the basin's hydrology by channeling water from contrasting watersheds—blackwater from the Shield and whitewater from the Andes and Llanos—creating a mixed riverine environment that influences downstream ecosystems without dominating specific flow contributions.[14] This integration supports the Orinoco's role as a major South American waterway, facilitating nutrient cycling and habitat connectivity across the basin.[3]Orinoco Delta

The Orinoco Delta, situated entirely within Venezuela along the Atlantic coast, spans approximately 22,000 km² and represents the terminal fan of the river system. This vast wetland is dissected by a complex array of distributary channels that form an intricate braided network of freshwater and brackish waterways, supporting a labyrinthine landscape of islands, swamps, and seasonal floodplains. The delta's structure is shaped by the interplay of fluvial processes and coastal dynamics, creating a non-centric morphology lacking large central lagoons but rich in interconnected channels and levees.[16][17][14] Prominent distributaries such as the Caño Manamo and Caño Macareo dominate the delta's eastern and western sectors, respectively, channeling the river's flow through meandering paths that branch into hundreds of smaller creeks and passages. Semi-diurnal tides exert significant influence, propagating upstream up to 200 km inland and modulating water salinity, flow regimes, and sediment distribution across the estuarine zone. This tidal reach fosters a gradient of habitats from freshwater-dominated upper reaches to brackish lower areas, enhancing the delta's ecological complexity.[14][17] Geologically, the delta is a young feature, primarily formed during the Holocene epoch through progradation and aggradation of sediments over the past 10,000 years, overlaying older Pleistocene substrates. Mangrove forests dominate the coastal and low-lying ecosystems, covering extensive tracts and providing critical habitat for biodiversity amid the wetland's flooded plains and tidal creeks; these forests stabilize sediments and buffer against erosion. Annually, the delta receives about 150 million tons of sediment from the Orinoco River, fueling ongoing deposition that drives morphological evolution and maintains the region's dynamic equilibrium. This sediment input is closely tied to the river's overall discharge patterns.[14][17]Hydrology

River Flow Characteristics

The Orinoco River exhibits a tropical hydrological regime strongly influenced by seasonal rainfall patterns associated with the migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone. High flows occur during the rainy season from May to November, driven by intense precipitation in the basin, with average discharges reaching approximately 40,000–50,000 m³/s and peaks up to 60,000–70,000 m³/s in August–September.[2][18] In the dry season from December to May, flows diminish markedly due to reduced rainfall, averaging around 10,000 m³/s with minima near 6,000 m³/s in March–April.[19] These fluctuations result in significant water level variations of 10–15 meters across the basin, affecting floodplain inundation and sediment dynamics.[20] A distinctive aspect of the Orinoco's flow is the Casiquiare River, a natural distributary that forms the world's largest interbasin canal, linking the upper Orinoco to the Amazon system via the Rio Negro. This channel diverts approximately 20–30% of the upper Orinoco's discharge, with an average flow of about 2,000–2,500 m³/s, enabling perennial water and sediment exchange between the two major basins.[21][22] The diversion's capacity varies seasonally, increasing during high-flow periods and contributing to the ecological connectivity of the regions.[23] The river transports an annual sediment load of approximately 240 million tons, primarily fine suspended particles from Andean and Guiana Shield sources, which influences water clarity and downstream deposition.[3] Water quality features a pH range of 5.5–7.5, with low alkalinity (often <1 meq/L) in blackwater tributaries but higher nutrient levels (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus from Andean inputs) in the main stem, fostering diverse aquatic communities including high fish biomass in nutrient-rich whitewater zones.[24][25] These profiles support robust primary production and biodiversity, though acidification in some reaches limits certain species.[26]Discharge Measurements

The Orinoco River exhibits one of the highest discharges among global rivers, with an average annual discharge at its mouth estimated between 35,000 and 37,000 cubic meters per second (m³/s), placing it third worldwide behind only the Amazon and Congo rivers.[27][28] This substantial outflow underscores the river's role in delivering vast volumes of freshwater to the Atlantic Ocean, contributing significantly to regional ocean salinity and nutrient dynamics. Key monitoring stations provide critical insights into discharge patterns along the lower Orinoco. At Ciudad Guayana, located approximately 335 km from the mouth near the confluence with the Caroní River, the average discharge is about 36,000 m³/s, reflecting contributions from major tributaries upstream.[3] Further upstream at Ciudad Bolívar, roughly 446 km from the mouth, the average discharge measures around 33,000 m³/s, capturing flow from a basin area exceeding 800,000 km².[29] These site-specific measurements highlight a progressive increase in volume downstream due to tributary inputs. Historical records dating back to 1926, primarily from the Ciudad Bolívar gauging station, reveal considerable interannual variability in discharge, with fluctuations driven by climatic oscillations such as El Niño and La Niña events.[28] El Niño phases typically correlate with reduced rainfall and lower discharges, while La Niña conditions enhance precipitation, leading to elevated flows.[30] Peak discharges have reached up to 70,000 m³/s during extreme wet-season floods, demonstrating the river's capacity for dramatic surges.[30] Long-term projections indicate decreases in precipitation and streamflows due to climate change, with rates of approximately 3.5 mm/decade under low-emission scenarios.[31]Geology

Basin Formation

The Orinoco Basin began forming during the Miocene epoch, approximately 23 to 5 million years ago, primarily as a result of the uplift of the Andes mountain range and the subsequent erosion of the adjacent Guiana Shield. This tectonic activity initiated flexural subsidence, creating a vast depositional area where sediments derived from both the eroding Precambrian rocks of the Guiana Shield to the east and the rising Andean cordillera to the west began to accumulate. The process marked a significant shift in regional paleogeography, transitioning from earlier wetland-dominated systems like the Pebas Mega-Wetland to more defined fluvial networks that would eventually shape the modern Orinoco River system.[32] The basin developed as a classic foreland depression situated between the dynamically uplifting Andes and the stable, ancient Guiana Shield, serving as a subsiding trough that captured massive volumes of terrigenous sediments. Over time, this led to a substantial sedimentary fill, reaching thicknesses of 5 to 10 kilometers in various parts of the basin, composed mainly of sandstones, shales, and conglomerates transported by proto-river systems. The foreland configuration was driven by the isostatic response to Andean orogenesis, with sediment influx peaking during phases of accelerated uplift in the middle to late Miocene, fundamentally defining the basin's architecture and accommodating the evolving drainage patterns of northern South America.[32][33] Underlying the entire basin is the Precambrian basement of the Guiana Shield, a 1.7-billion-year-old cratonic block that exerts a profound control on the river's course by presenting resistant, low-relief highlands that channel the Orinoco's flow along structural trends. This ancient foundation not only dictates the basin's topographic grain but also hosts significant mineral deposits, such as gold and bauxite, resulting from prolonged weathering and concentration processes on the shield's exposed surfaces. The interaction between the stable shield basement and overlying Cenozoic sediments highlights the basin's dual nature as both a tectonic depository and a geomorphic conduit shaped by long-term erosion.[34]Eastern Venezuelan Basin

The Eastern Venezuelan Basin, a major component of the Orinoco River's drainage system, features a thick sedimentary sequence spanning the Cretaceous to Tertiary periods, with accumulations reaching up to 12 kilometers in thickness. These sediments primarily consist of marine shales, sandstones, and carbonates deposited in a foreland basin setting influenced by Andean orogeny and Caribbean plate interactions.[35][36] Key hydrocarbon source rocks within this sequence include the Upper Cretaceous La Luna Formation in the western parts and its eastern equivalent, the Querecual Formation, both renowned for their organic-rich shales with high total organic carbon content. The Querecual Formation, in particular, comprises alternating foraminiferal carbonates and laminated mudrocks exceeding 450 meters in thickness, serving as the primary source for much of the basin's oil generation through kerogen maturation under burial depths.[37][38] The Orinoco Belt, also known as the Faja Petrolífera del Orinoco, represents a significant accumulation of extra-heavy oil within these Tertiary sediments, particularly in the Oficina and Merecure formations, with estimated original oil in place totaling 1.3 trillion barrels. This vast deposit formed through updip migration from Cretaceous sources into Miocene reservoirs under the influence of regional subsidence.[39][40] Structurally, the eastern basin is characterized by fault blocks and anticlines resulting from tectonic compression along the Caribbean-South American plate boundary, including thrust faults and fold-thrust systems that deform the sedimentary pile. These features, such as the Anaco Fault and associated domes, create traps for hydrocarbons by juxtaposing reservoir sands against impermeable shales.[41][42]History

Early Exploration and Indigenous Use

The Orinoco River has been integral to indigenous lifeways for millennia, serving as a primary corridor for mobility, sustenance, and exchange. Archaeological evidence from the Orinoco basin indicates human occupation dating back to around 10,000 years ago, during the early Holocene, with recent findings indicating occupation as early as 12,600 years ago in sites like Serranía La Lindosa.[43] These early inhabitants adapted to the river's seasonal floods and diverse ecosystems, establishing semi-permanent settlements along its banks and tributaries.[44][45] Pre-colonial indigenous societies, including the Warao in the expansive delta, the Pemon in the southern highlands, and the Yanomami along the upper reaches, relied heavily on the Orinoco for daily survival and inter-community connections. The Warao, renowned for their mastery of canoe-building, navigated the labyrinthine delta channels using large dugout vessels to fish for species like piranha and catfish, while also harvesting manatee and transporting goods such as cassava and fibers. The Pemon and Yanomami, meanwhile, traversed the river and its rapids-strewn sections for trade, exchanging highland products like quartz tools and honey for lowland staples including salt and medicinal plants, fostering extensive networks across the basin. These practices underscored the river's role as a cultural and economic lifeline, shaping social structures and spiritual beliefs tied to its rhythms. European contact with the Orinoco commenced in the late 15th century, marking a pivotal shift in the river's historical narrative. On his third voyage in 1498, Christopher Columbus approached the South American coast and encountered the Orinoco's mouth near present-day Trinidad, observing its immense freshwater discharge into the Atlantic—estimated at over 30,000 cubic meters per second—which convinced him of the presence of a vast continental landmass rather than an island. Sailing briefly into the delta's outlets, Columbus's crew interacted with coastal indigenous groups, gathering initial intelligence on the river's interior, though they did not ascend it significantly.[46] The first dedicated European ascent occurred in 1531 under Spanish conquistador Diego de Ordaz, who launched his expedition from the Pearl Coast (modern Venezuela) with around 400 men in search of the fabled El Dorado. Ordaz navigated upstream approximately 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) from the delta, reaching near the Meta River confluence, contending with swift currents, malaria, and skirmishes with local tribes such as the Guamo and other indigenous groups, before harsh conditions forced a retreat. This perilous journey yielded rudimentary maps and accounts of the river's lower course, fueling Spanish ambitions for further penetration despite high casualties.[47] In the 17th century, Jesuit missionaries extended European influence inland by founding missions along the Orinoco's tributaries, such as the Meta and Cinaruco, to convert and organize indigenous communities under Spanish colonial oversight. These outposts, often staffed by small groups of priests, incorporated river canoes for outreach, blending evangelism with agriculture and herding to sedentarize nomadic groups like the Guahibos. By the century's end, allocations of resources to Orinoco missions supported up to a dozen stations, though many faced abandonment due to indigenous resistance and logistical strains.[48] A landmark scientific foray came in 1800 with Prussian explorer Alexander von Humboldt, who, accompanied by botanist Aimé Bonpland, ascended the upper Orinoco from Angostura (now Ciudad Bolívar) over several months, enduring rapids and isolation to map its meandering path toward the Colombian border. Humboldt's surveys documented the river's hydrology, flora, and the enigmatic Casiquiare canal—a natural waterway linking the Orinoco to the Amazon—producing precise charts that corrected prior inaccuracies and highlighted the basin's ecological interconnectedness. His work, detailed in later publications, established the Orinoco's full extent at over 2,000 kilometers and influenced global understandings of tropical geography.[49][50]Colonial and Modern Developments

During the Spanish colonial period, the Orinoco River served as a strategic frontier, prompting the establishment of fortified settlements to counter incursions from British and Dutch forces in the Guianas. In 1764, Spanish authorities relocated the settlement of Santo Tomé de Guayana to a narrower section of the river, founding Angostura (now Ciudad Bolívar) as a defensive outpost approximately 260 miles (420 km) upstream from the delta. This fortified port was designed to protect Spanish interests in the resource-rich interior against European rivals and indigenous resistance, marking a shift toward more permanent control over the Orinoco basin.[51][52] The river played a pivotal role in the 19th-century wars of independence, particularly during Simón Bolívar's campaign against Spanish rule. In early 1819, Bolívar established his headquarters in the Orinoco region at Angostura, using the river's Llanos (plains) as a base to regroup his forces amid ongoing conflict. From there, he led a daring march across the flooded Orinoco basin during the rainy season, navigating treacherous terrain to reach the Andes and launch a surprise offensive into New Granada (modern Colombia), culminating in victories that accelerated the liberation of northern South America. Post-independence, the Orinoco became central to lingering territorial disputes; the boundary between Venezuela and Colombia, contested since the dissolution of Gran Colombia in 1830, was finally resolved through arbitration by the Swiss Federal Council in 1922, which delineated the frontier along the river's upper reaches and adjacent areas, with demarcation completed by 1932.[53][54] In the 20th century, modern infrastructure transformed the Orinoco into a key economic artery. The Guri Dam, constructed on the Caroní River (a major Orinoco tributary), began operations in its first phase in 1978 with an initial capacity of about 2,065 megawatts, expanding to a total installed capacity of 10,200 megawatts by 1986 and becoming one of the world's largest hydroelectric facilities. This project, initiated in 1963, harnessed the river system's vast hydropower potential to support Venezuela's industrialization and energy needs. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, efforts have been made to improve navigation on the Orinoco through dredging and infrastructure developments to enhance cargo transport from the interior to ports near the delta, boosting trade with Brazil and beyond.[15]Ecology

Biodiversity

The Orinoco River basin supports one of the most diverse freshwater ecosystems in the world, encompassing a wide array of habitats that foster exceptional species richness.[1] The basin harbors more than 1,000 species of fish, including iconic representatives such as the arapaima (Arapaima gigas), a large air-breathing fish that inhabits floodplain lakes and river channels, and various piranha species (Serrasalmus spp.), known for their schooling behavior in slower waters.[1][14] Among mammals, the basin is home to predators like the jaguar (Panthera onca), which prowls riparian zones, and the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), the world's largest rodent that thrives in aquatic grasslands.[1] The Orinoco river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis), a freshwater cetacean endemic to the region, is classified as endangered, with an estimated population of approximately 2,800 individuals in the Orinoco basin (as of 2012) confined to riverine and floodplain environments.[55] Avian diversity in the Orinoco basin exceeds 1,300 species, reflecting the varied ecosystems from upstream highlands to downstream wetlands.[1] Notable birds include the scarlet ibis (Eudocimus ruber), which nests in large colonies within the delta's mangrove islands, and the hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin), a unique folivore associated with flooded forests where its chicks use wing claws for climbing.[1][14] The basin's vegetation spans diverse biomes, including tepui cloud forests on the ancient Guiana Shield plateaus, characterized by endemic bromeliads and orchids adapted to misty, nutrient-poor soils; expansive llanos savannas with grasses like Axonopus and scattered gallery forests along rivers; and mangrove swamps in the Orinoco Delta, dominated by red (Rhizophora mangle) and black (Avicennia germinans) mangroves that stabilize coastal sediments.[1][56] Several species are endemic to the Orinoco system, underscoring its role as a center of unique evolutionary adaptation. The Orinoco crocodile (Crocodylus intermedius), the largest predator in South American freshwaters, is critically endangered with fewer than 250 mature adults remaining, primarily in remote floodplain rivers and lakes where it preys on fish and caimans. Recent reintroduction efforts have released over 80 juvenile and adult individuals into the basin (as of 2023).[14][57] Flooded forests serve as critical habitats, providing seasonal inundation that supports nutrient cycling, fish spawning grounds, and refuge for terrestrial species during dry periods.[1] These dynamic ecosystems highlight the basin's interconnected biodiversity, though many species face ongoing threats from habitat alteration.[1]Environmental Challenges

The construction of major dams such as the Tocoma Dam on the Caroní River, a key tributary of the Orinoco, has fragmented aquatic habitats and disrupted natural hydrologic regimes, leading to reduced sediment transport and obstruction of migratory routes for fish species like migratory catfishes and characins. These alterations impede upstream and downstream movements essential for reproduction and feeding, contributing to declines in native fish populations across the basin. Additionally, artisanal gold mining in the Orinoco basin releases mercury into waterways, contaminating fish and affecting extensive areas, including the Caura River sub-basin where over 90% of tested indigenous populations show elevated mercury levels in their blood.[58] Deforestation within the Orinoco basin has resulted in substantial forest cover loss, with Venezuela's tree cover—much of which overlaps the basin—declining by approximately 5% from 2001 to 2024, driven by agricultural expansion and mining activities that exacerbate soil erosion and habitat degradation.[59] In the Orinoco Mining Arc, a critical portion of the basin, vegetation changes between 2000 and 2020 have further intensified these pressures, converting forests to barren land and open water bodies.[60] Oil spills from operations in the Orinoco Belt have also impacted delta wetlands, with incidents such as the 2022 crude leak near fishing communities contaminating morichales (palm swamps) and moriches, leading to degradation of these vital ecosystems that support mangrove and flooded forest biodiversity.[61] Climate change projections indicate potential increases in extreme precipitation events over the Orinoco basin, with models suggesting up to 60% rises in maximum 20-day rainfall by the end of the century, which could exacerbate flooding despite overall declines in mean streamflow under high-emission scenarios.[62][63] These shifts heighten risks to riparian habitats and settlements through more frequent inundations. Furthermore, environmental alterations from dams and hydrological changes have facilitated the introduction of invasive species, such as tilapia and peacock bass (Cichla spp.), which outcompete native fishes in reservoirs and altered river segments, further threatening the basin's ecological balance.[64] These challenges compound pressures on the Orinoco's biodiversity, as detailed in the biodiversity section.Human Aspects

Settlements and Navigation

The Orinoco River supports several major human settlements along its course, serving as a vital lifeline for transportation and urban development in Venezuela. Ciudad Bolívar, located approximately 400 km upstream from the river's delta, is a key historical and administrative center with a population of around 427,000 as of 2025.[65] Founded in 1764 as San Tomás de la Nueva Guayana de la Angostura, it played a pivotal role during Venezuela's independence wars, hosting the Angostura Congress in 1819 where Simón Bolívar established the framework for the republic.[52] Further downstream near the delta, Ciudad Guayana—comprising the conjoined cities of Puerto Ordaz and San Félix—functions as a major industrial hub with a metropolitan population exceeding 991,000 in 2025.[65] At the river's upper reaches near the Colombian border, Puerto Ayacucho, the capital of Amazonas state, has a population of about 130,000 as of 2024 and serves as a gateway for regional trade and river access.[66] Navigation on the Orinoco is extensive, with the river navigable for over 1,000 km from Puerto Ayacucho downstream to the Atlantic, facilitating both small craft and larger vessels.[67] Ocean-going ships can reach Ciudad Guayana, roughly 360 km from the mouth, thanks to ongoing dredging efforts that maintain channel depths of up to 10 meters.[68] The port facilities at Puerto Ordaz handle significant bulk cargo, including iron ore and bauxite, underscoring the river's economic importance for resource transport. Ciudad Bolívar's port further supports regional distribution, accommodating vessels for general cargo and passenger services.[69] Indigenous communities, such as the Warao in the delta region, have long relied on traditional landing sites and small ports for canoe-based navigation and trade along the river.[70] Modern infrastructure complements these, with facilities like the Matanzas terminal at mile 196 enabling deeper-draft access for commercial shipping.[68] However, navigation faces seasonal challenges, particularly during the dry period from November to April, when low water levels and shallow drafts necessitate frequent dredging to counteract heavy sediment loads and ensure safe passage for larger vessels.[71] These constraints can limit vessel size and frequency, impacting efficiency during peak cargo periods.[72]Economic Resources

The Orinoco Basin hosts significant extractive industries, with oil being the dominant resource. The Orinoco Belt, encompassing vast deposits of extra-heavy crude oil, accounted for the majority of Venezuela's petroleum output in 2023, when national production averaged approximately 761,000 barrels per day; production has since increased to around 1.1 million barrels per day as of mid-2025.[73] Much of it is processed through specialized upgraders that convert the viscous bitumen into lighter synthetic crude suitable for export and refining.[74] These upgraders, including facilities like the Petrocaballero and Petromonagas plants, handle the Belt's high-sulfur, high-viscosity oil, enabling sustained extraction despite technical challenges and international sanctions, which have prompted recent partnerships with foreign firms.[75] Mining operations in the basin focus on iron ore, bauxite, and gold, primarily within the Orinoco Mining Arc spanning the river's southern tributaries. The El Florero iron mine, discovered in 1926 near the Orinoco Delta south of San Félix, forms part of Venezuela's extensive iron reserves, estimated at over 4 billion metric tons of high-grade ore across the region, supporting steel production at facilities like Siderúrgica del Orinoco (Sidor); recent deals, such as India's Jindal Group assuming operations in 2024, aim to revive output.[76][77] Bauxite deposits occur along tributaries in Bolívar State, while gold mining—often illicit—targets alluvial placers in the Arc, yielding thousands of kilograms annually amid environmental concerns.[78][58] Agriculture and fisheries leverage the basin's fertile floodplains and wetlands for economic output. In the Llanos plains drained by the Orinoco and its tributaries, extensive cattle ranching dominates, with millions of head grazing seasonally flooded savannas to produce beef and dairy, forming a cornerstone of Venezuela's livestock sector and supporting rural livelihoods through dual-purpose herds.[79] The Orinoco Delta's mangrove estuaries sustain shrimp fisheries, particularly for white shrimp (Penaeus schmitti), with artisanal and industrial catches contributing to national seafood production, though yields fluctuate due to overfishing and habitat loss.[80] Hydropower generation from the Caroní River, the Orinoco's largest tributary, provides a renewable economic pillar. The Guri Dam and associated cascade facilities generate over 10,000 megawatts, supplying approximately 70% of Venezuela's electricity needs through massive reservoirs that harness the river's steep Andean drop, though recent droughts and infrastructure issues have reduced reliability, contributing to nationwide blackouts.[81][82] This infrastructure, managed by Corporación Venezolana de Guayana (CVG), underpins industrial energy demands while mitigating reliance on fossil fuels.[15]Culture

Indigenous Cultures

The Orinoco River basin is home to diverse indigenous groups whose traditional societies are deeply intertwined with the river's ecosystems. The Warao, primarily inhabiting the delta region, numbered around 49,000 individuals as of the 2011 census and maintain a canoe-based lifestyle centered on the waterways, viewing themselves as the "masters of the canoe" or guardians of the river in their foundational myths.[83][6] Their subsistence relies heavily on fishing using efficient techniques such as spears, bows, and traps adapted to the delta's smaller rivers and lagoons, supplemented by gathering larvae, crustaceans, and fruits, with limited horticulture including cassava cultivation.[84][85] In the middle basin, the Piaroa, with an estimated population of about 15,000 as of the early 2000s, practice slash-and-burn horticulture as their primary economic activity, cultivating crops like plantains and manioc in forest clearings while integrating hunting and gathering.[86][87] Their social organization emphasizes endogamous kinship groups, fostering communal land use and cultural continuity amid the tropical forests.[88] Further upstream along the upper tributaries, the Yanomami, part of a larger group totaling around 45,000 across the border with Brazil as of the early 2020s, engage in shifting cultivation, rotating gardens of bananas, cassava, and other staples to maintain soil fertility, complemented by hunting and foraging in the rainforest.[89][90] These groups' cultural practices reflect a profound dependence on the Orinoco's rhythms, evident in Warao myths that narrate origins tied to water spirits and celestial descents, reinforcing their identity as river people who navigate vast mangrove networks in dugout canoes for trade and rituals.[91] Piaroa traditions similarly embed ecological knowledge, with horticultural cycles dictating seasonal mobility and shamanic practices that invoke forest guardians for bountiful yields.[92] Among the Yanomami, riverine myths and communal shabono villages underscore collective resource management, where shifting cultivation plots are cleared collaboratively and abandoned after a few years to allow regeneration, sustaining their semi-nomadic patterns.[89] Historical resistance to external pressures, such as the 1990s efforts toward land demarcations in Venezuela's Amazonas and Delta Amacuro states, highlighted these communities' advocacy for territorial integrity against encroaching settlers and resource extractors.[93] As of the early 2010s, approximately 200,000 indigenous people resided in the Orinoco basin, facing ongoing challenges to their lands and ways of life. Venezuela's ratification of International Labour Organization Convention 169 in 2002 affirms indigenous rights to free, prior, and informed consent for projects affecting their territories, yet implementation remains inconsistent, particularly amid the expansion of the Orinoco Mining Arc since 2016.[94] Illegal and state-backed mining operations have displaced communities, polluting rivers with mercury and disrupting traditional fishing and cultivation, as seen in Yanomami territories where garimpeiros (illegal miners) have invaded demarcated areas, leading to health crises and cultural erosion. As of 2025, illegal mining continues to expand, with significant deforestation (e.g., 4,781 hectares in Imataca) and health impacts (e.g., over 570 child deaths in Yanomami territory in 2024 from malnutrition and disease) reported in Yanomami and Pemón territories.[95][96][97][98] Warao and Piaroa groups similarly contend with habitat loss from extraction, prompting migrations and legal struggles to enforce ILO 169 protections and secure communal titles.[99]Representation in Media and Recreation

The Orinoco River has inspired various cultural representations in music, literature, and visual media, often emphasizing themes of exploration and natural wonder. Irish singer Enya's 1988 single "Orinoco Flow" from her album Watermark captures the river's evocative flow in its lyrics and melody, drawing partial inspiration from the waterway despite the title's primary reference to the Orinoco recording studios.[100] In literature, French author Jules Verne's 1898 novel The Mighty Orinoco portrays an adventurous expedition up the uncharted river in Venezuela, where a young protagonist searches for his father amid perilous landscapes and indigenous encounters.[101] The river's delta and basin feature prominently in films and documentaries depicting expeditions and historical narratives, such as the surreal Venezuelan production Orinoko, Nuevo Mundo (1984) by Diego Rísquez, which explores the pre- and post-conquest history of the Orinoco region through speechless, multi-faceted visuals.[102] Other examples include National Geographic's short documentary on the Orinoco, which follows explorers through Venezuela's biodiverse waterways, and the full-length Orinoco Basin film by Planet Doc, highlighting remote journeys into the delta.[103][104] Recreational activities along the Orinoco emphasize eco-tourism in the delta, where birdwatching tours allow visitors to spot species like toucans, macaws, and herons in the mangrove floodplains.[105][106] Fishing events, such as the annual Feria de la Sapoara in August, center on sustainably harvesting the native sapoara fish unique to the river, combining tradition with community gatherings.[107] Adventure rafting on rapids like the Raudal de Atures offers high-adrenaline descents during the rainy season due to the Orinoco's expansive width.[108] In sports, the Orinoco hosts Venezuelan rowing and paddling events, including endurance challenges that test participants on its currents.[109] Some indigenous games from basin communities, such as archery and canoe-based relays rooted in traditional practices, have been adapted for inclusion in modern multi-sport gatherings like the World Indigenous Games.[110]References

- https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q372920