Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Orongo

View on Wikipedia

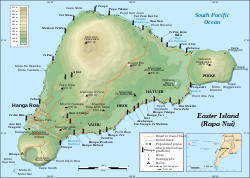

Orongo (Rapa Nui pronunciation: [oˈɾoŋo]; Spanish pronunciation: [oˈɾoŋgo]) is a stone village and ceremonial center at the southwestern tip of Rapa Nui (Easter Island). It consists of a collection of low, sod-covered, windowless, round-walled buildings with even lower doors positioned on the high south-westerly tip of the large volcanic caldera called Rano Kau. Below Orongo on one side a 300-meter barren cliff face drops down to the ocean; on the other, a more gentle but still very steep grassy slope leads down to a freshwater marsh inside the high caldera.

In 1974 UNESCO sponsored a project to restore Orongo. Under the supervision of William Mulloy, with the support of Rapanui archaeologist Sonia Haoa Cardinali, the first half of the ceremonial village's 53 stone masonry houses was investigated and restored in 1974. The remainder was completed in 1976 and subsequently investigated in 1985 and again in 1995. Orongo now has World Heritage status as part of the Rapa Nui National Park.

History

[edit]69 Between the 18th and mid-19th centuries Orongo was the centre of a birdman cult whose defining ritual was an annual race to bring the first manutara (sooty tern) egg back undamaged from the nearby islet of Motu Nui to Orongo. The race was very dangerous, and hunters often fell to their deaths from the cliff face or were killed by sharks. The site has numerous petroglyphs, mainly of tangata manu (birdmen), which may have been carved to commemorate some of the winners of this race.

In the 1860s, most of the Rapa Nui islanders died of disease or were enslaved, and when the survivors were converted to Christianity, Orongo fell into disuse. In 1868, the crew of HMS Topaze removed the huge basalt moai known as Hoa Hakananai'a from Orongo. It is now housed in the British Museum.

The site of Orongo was included in the 1996 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund, and listed again four years later, in 2000. The threat was soil erosion, caused by rainfall and exacerbated by foot traffic.[1] After 2000, the organization helped devise a site management plan with support from American Express, and in December 2009 more funding was announced for the construction of a sustainable visitor center.[2]

-

Restored stone houses at Orongo

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ World Monuments Fund - Easter Island (Rapa Nui) Archived 2010-12-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "World Monuments Fund and American Express announce funding for a sustainable visitor reception center on Easter Island, Chile" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-21. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

Resources

[edit]- Mulloy, William. Investigation and Restoration of the Ceremonial Center of Orongo. International Fund for Monuments Bulletin No. 4. New York (1975).

- Mulloy, W.T., and S.R. Fischer. 1993. Easter Island Studies: Contributions to the History of Rapanui in Memory of William T. Mulloy. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Routledge, Katherine Pease (Scouresby). 1919. The Mystery of Easter Island; the Story of an Expedition. London, Aylesbury, Printed for the author by Hazell, Watson and Viney. ISBN 0-932813-48-8 (1998 US reprint)

External links

[edit]Orongo

View on GrokipediaLocation and Physical Setting

Geographical Position

Orongo is situated at the southwestern tip of Rapa Nui, Chile, on the rim of the Rano Kau volcanic crater, with precise coordinates of approximately 27°11′S 109°26′W.[4] This location places it along a narrow strip between the crater's inner edge and sheer cliffs descending to the Pacific Ocean, directly overlooking the offshore islets of Motu Nui, Motu Iti, and Motu Kao Kao.[5][2] The site rests at an elevation of roughly 300 meters above sea level, adjacent to the Rano Kau crater lake, which lies about 100 meters lower within the caldera.[6][7] These topographic features—steep volcanic slopes, high cliffs, and oceanic exposure—enhance the area's physical isolation, with the crater rim providing a natural barrier inland.[8] Accessibility from Hanga Roa, located 6 kilometers to the northeast, occurs primarily via a winding trail or vehicular road ascending the volcano's flanks, underscoring the site's remote perch.[9][10]Architectural and Environmental Features

Orongo features a cluster of approximately 54 low, elongated stone houses, termed hare moa, arranged in three semi-independent groups along the southwestern rim of the Rano Kau volcanic crater. These structures exhibit boat-shaped foundations, typically 10-15 meters long and 3-4 meters wide, built atop low stone platforms or ahu-like bases using stacked basalt slabs without mortar.[2][11] The houses possess narrow, low entrances—often less than 1 meter high—forcing occupants to enter on hands and knees, a design that minimized exposure to the site's relentless winds exceeding 50 km/h on average.[12][3] Construction relied on local volcanic resources, including fine-grained basalt slabs known as kehu quarried from nearby outcrops and shaped using obsidian tools sourced from Rano Kau's own deposits. Roofs, originally thatched with local grasses, were supported by wooden rafters and now appear sod-covered due to weathering and restoration efforts. The absence of windows and minimal interior space—divided into hearth areas and storage—reflects utilitarian adaptations to the harsh, resource-scarce environment.[3][13] The site's environmental context encompasses the steep, inward-facing crater walls of Rano Kau, a water-filled volcanic caldera rising 300 meters above sea level, surrounded by jagged lava fields devoid of soil cover. Prevailing southeast trade winds amplify erosion on the exposed clifftop, while the terrain integrates directly with offshore basalt islets—Motu Nui, Motu Iti, and the stack of Motu Kao Kao—approximately 1-2 km distant, providing isolated nesting habitats for sooty terns (Onychoprion fuscatus) amid otherwise limited avian resources on the island. This positioning underscores the interplay between Orongo's built forms and the volcanic archipelago's ecological constraints.[3][2]Historical Context

Pre-Orongo Developments on Rapa Nui

Polynesian voyagers settled Rapa Nui around AD 1200, as indicated by radiocarbon dating of early archaeological sites and genetic analyses confirming East Polynesian origins without pre-European admixture from other regions.[14] [15] This colonization initiated a phase of agricultural adaptation, including the cultivation of crops like sweet potatoes and taro in stone-mulched gardens (manavai), which supported initial population growth to an estimated 3,000 individuals by the peak moai era, rather than the higher figures once proposed that implied subsequent collapse.[16] [14] Society organized into approximately ten clans (mata or mata'e), each controlling defined territories and led by hereditary chiefs (ariki), fostering a hierarchical structure with distinct classes including priests (ivi-atua) and warriors (matatoa).[17] [18] This clan-based system emphasized lineage and ancestor veneration, evident in oral traditions tracing descent from the founding chief Hotu Matu'a, and laid groundwork for inter-clan competition over resources and prestige.[17] From roughly AD 1200 to 1600, Rapanui society entered the moai construction phase, carving nearly 1,000 monolithic statues from Rano Raraku quarry to represent deified ancestors, which were erected on coastal platforms (ahu) facing inland settlements.[19] Experimental replications demonstrate that moai could be transported upright over land using ropes and a small team rocking the statue side-to-side in a "walking" motion, requiring minimal timber and thus challenging claims of deforestation-driven transport crises.[20] [21] The island's palm-dominated forests declined during this period, but empirical evidence from seed predation studies and pollen cores attributes significant causation to introduced Polynesian rats (Rattus exulans) consuming palm nuts and inhibiting regrowth, rather than solely human clearing for agriculture or statue movement.[22] [23] Human activities contributed through fire and selective felling, yet archaeological data reveal no widespread pre-contact societal collapse or ecocide; instead, adaptations like rock gardening sustained productivity, with population levels remaining viable into European contact.[16] [24] This resilience in resource management and clan dynamics positioned Rapanui for evolving ritual competitions amid environmental pressures.[15]Emergence of the Birdman Cult

Archaeological evidence indicates that the Birdman cult, also known as the Tangata Manu cult, emerged at Orongo during the mid-15th to early 16th century CE. Radiocarbon dating of short-lived plant materials from house fills and contexts associated with petroglyphs at the site supports this chronology, with calibrated dates clustering around AD 1400–1550 for the initial construction and use phases of the ceremonial village.[25][26] These dates derive from excavations of over 50 ahu (house platforms) at Orongo, revealing a rapid buildup of settlement layers linked to cult activities.[27] The cult's rise coincided with a broader transition away from the earlier moai ancestor veneration, as evidenced by the cessation of moai transport and erection around the 15th–16th centuries, potentially driven by ecological pressures such as deforestation and resource scarcity documented in paleoenvironmental records.[28] Oral traditions recorded by early European visitors describe periods of famine and conflict preceding the cult's prominence, though these accounts lack precise dating and may reflect later amplifications.[29] Empirical data from pollen cores and soil analyses indicate declining agricultural productivity and drought episodes around this time, suggesting causal factors in the ritual shift without implying societal collapse.[26] Early manifestations include the appearance of petroglyphs depicting the creator deity Make-Make and hybrid birdman figures (tangata manu), concentrated at Orongo with over 400 carvings identified, marking an innovation in Rapa Nui iconography distinct from prior moai-related motifs.[25] These rock arts, pecked into basalt outcrops overlooking the motu islets, align temporally with the radiocarbon sequence, indicating the cult's ritual focus on avian fertility symbols as a novel ideological adaptation.[30] The absence of earlier birdman representations elsewhere on the island underscores Orongo's role as the cult's origin point.[26]Duration and Key Phases

The ceremonial use of Orongo spanned primarily from the mid-16th century to the mid-19th century, with peak activity occurring between the 16th and mid-18th centuries, coinciding with the height of the tangata manu (Birdman) cult rituals.[31][32] These annual ceremonies were synchronized with the breeding season of the sooty tern (Onychoprion fuscatus), typically commencing in September, when competitors swam to offshore islets to retrieve the first egg, symbolizing divine favor.[33] Archaeological evidence delineates three key phases of development and intensification at Orongo. The early phase, around the mid-1500s, involved initial iconographic elaboration, including the carving of petroglyphs depicting birdman motifs and the construction of foundational stone houses along the crater rim, marking the emergence of cult-specific activities distinct from prior island-wide practices.[31] This period is evidenced by the onset of stratified deposits in front of the houses, indicating ritual gatherings and offerings.[25] Intensification characterized the 17th century, with expansion to approximately 54 houses forming clustered sets, reflecting increased participation and elaboration of ceremonial infrastructure to accommodate larger-scale competitions and observances.[2] Radiocarbon dating from associated deposits supports this buildup, showing continuous reuse and accumulation of materials like obsidian tools and faunal remains from ritual feasts.[34] The late phase, extending into the 18th and early 19th centuries, featured modifications to existing structures, such as reinforcements and adaptations for prolonged use, corroborated by deeper stratigraphic layers revealing layered refuse and repair episodes without evidence of abandonment until external disruptions. This continuity underscores Orongo's role as a persistent focal point for the cult, with activities documented ethnohistorically up to around 1867.[32]Factors in Decline

The ceremonial activities at Orongo ceased in the mid-1860s, primarily due to the disruptive impacts of Peruvian slave raids and subsequent missionary interventions rather than pre-existing environmental collapse. Between late 1862 and mid-1863, Peruvian raiders abducted over 1,000 Rapa Nui inhabitants—constituting at least 75% of the island's population of approximately 3,000–4,000—severely undermining the social structures necessary for sustaining the Birdman cult's rituals, including the annual competitions that required organized clans and knowledgeable participants.[35] This demographic catastrophe, compounded by introduced diseases such as smallpox, reduced the surviving population to around 111 individuals by 1864, disrupting continuity of oral traditions and ceremonial expertise essential to Orongo's functions.[35] Missionary efforts further accelerated abandonment through active suppression of indigenous practices. Following the raids, Catholic and Protestant missionaries arrived in 1864–1868, converting survivors and prohibiting pagan rituals, including the Tangata Manu competitions; eyewitness accounts from the period document the destruction of ritual paraphernalia and enforcement of Christian norms, leading to the physical neglect of Orongo's stone houses and petroglyphs as sacred sites lost their cultural relevance.[35] Archaeological surveys indicate that post-1860s layers at Orongo show no evidence of continued use, with structures succumbing to erosion without maintenance, aligning with oral histories of ritual cessation under missionary influence rather than gradual internal decay.[25] While some skeletal analyses reveal isolated instances of violence, such as cranial fractures in pre-contact remains, these do not indicate widespread warfare or societal collapse sufficient to end Orongo's practices independently of external shocks; frequencies of violent trauma remain low (e.g., under 3% in sampled crania), suggesting intermittent conflict rather than a causal driver of the cult's demise.[36] Declines in seabird populations may have strained ritual resources, but empirical records prioritize contact-era events—raids, disease, and suppression—as the decisive factors, challenging narratives overemphasizing autonomous ecocide for the Birdman era's end.[35][37]The Tangata Manu Cult

Core Rituals and Competitions

The core ritual of the tangata manu cult centered on an annual competition held in September at Orongo, involving representatives known as hopu manu from competing clans who sought to retrieve the first egg of the sooty tern (manu tara, Onychoprion fuscatus) laid on Motu Nui, a small offshore islet approximately 1.2 kilometers from the Rano Kau crater rim.[38][35] Participants were often selected through dreams interpreted by an ivi-atua, a divinely inspired individual, or inherited rights within clans.[38] The event commenced with clans assembling at Orongo, where the hopu manu departed from the cliff edge, propelling themselves across the channel using a reed bundle (pora) for flotation while facing strong currents and swells.[38][35] Upon reaching Motu Nui, the hopu manu took shelter in a cave to await the terns' arrival and nesting, then scaled the islet's cliffs to locate and secure the first egg in a reed basket or bundle.[38] The successful competitor signaled victory by shouting across the water to observers on the mainland, after which they swam back to the Rano Kau shore, ascended the steep 300-400 meter cliffs to Orongo, and presented the egg to their sponsoring chief (moari).[38] This return journey involved fasting while safeguarding the egg, which was ritually dipped in the sea upon retrieval.[38] The chief of the victorious clan was then declared tangata manu and underwent a ceremonial procession to designated houses at Orongo for the egg's incubation and handling, including hanging it in the structure and blowing it empty on the third day to insert tapa cloth.[38] The competition entailed severe physical risks, including shark attacks, drowning in rough seas, exhaustion from the multi-stage exertion, and fatal falls during cliff ascents or descents.[38][35] Following victory, the tangata manu entered a year of isolation in a stone house, cave, or retreat such as Take near Rano Raraku, adhering to strict taboos that prohibited washing and required extended periods of sleep, while being provisioned with food by servants.[38] Markings of status included head shaving followed by red painting, later a hair crown (hau oho), and tattooing with designs such as forehead rings or body patterns resembling dark-blue breeches.[38] The tangata manu received a new name upon success and remained secluded for about five months under intensified restrictions before resuming limited activities.[38]