Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Head shaving

View on Wikipedia

Head shaving, also known as being bald by choice,[1] is the shaving of the hair from a person's head. People throughout history have shaved all or part of their heads for diverse reasons including aesthetics, convenience, culture, fashion, practicality, punishment, a rite of passage, religion, or style.

Early history

[edit]The earliest historical records describing head shaving are from ancient Mediterranean cultures such as Egypt, Greece, and Rome. The Egyptian priest class ritualistically removed all hair from head to toe by plucking it.

Religious significance

[edit]Many Buddhists and Vaisnavas, especially Hare Krishnas, shave their heads. Some Hindu and most Buddhist monks and nuns shave their heads upon entering their order, and Buddhist monks and nuns in Korea have their heads shaved every 15 days.[2] Muslim men have the choice of shaving their heads after performing the Umrah and Hajj, following the tradition of committing to Allah, but are not required to keep it permanently shaved.[3]

As a symbol of subordination

[edit]Enslaved peoples

[edit]

In many cultures throughout history, cutting or shaving the hair on men has been seen as a sign of subordination. In ancient Greece and much of Babylon, long hair was a symbol of economic and social power, while a shaved head was the sign of a slave. This was a way of the slave-owner establishing the slave's body as their property by literally removing a part of their personhood and individuality.[4]

Military

[edit]The practice of shaving heads has been widely used in the military. Although sometimes explained as being for hygiene reasons, the image of strict and disciplined conformity is also accepted as a factor.[5] Upon the Allied invasion of Normandy during World War II, some Allied soldiers shaved their heads to deny any Nazis the opportunity to grab it during hand-to-hand combat. [citation needed] For the new military recruit, it can be a rite of passage, and variations of it have become a badge of honor.[6]

Prison and punishment

[edit]Prisoners commonly have their heads shaven to prevent the spread of lice, but it may also be used as a demeaning measure. Having the head shaved can be a punishment prescribed in law.[7] Nazis punished people accused of racial mixing by parading them through the streets with shaved heads and placards around their necks detailing their acts.[8]

During and after World War II, thousands of French women had their heads shaved in front of cheering crowds as punishment for either collaborating with the Nazis or having sexual relationships with Nazi soldiers during the war.[9][10][11] Some Finnish women also had their heads shaved for allegedly having relationships with Soviet prisoners of war during the war.[12]

Practicality

[edit]Sport

[edit]

Competitive swimmers, sprinters, and joggers sometimes seek to gain an advantage by completely removing all hair from their entire body to reduce drag while competing.

Baldness

[edit]People experiencing hair loss may shave their heads in order to look more presentable, for convenience, or to adhere to a certain style or fashion movement. Those with alopecia areata or pattern hair loss often choose to shave their heads, which has become exponentially more common and socially acceptable since the 1990s.[13]

Notable people

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled List of people with shaved heads. (Discuss) (July 2025) |

Real

[edit]This list includes only public figures for whom a shaved head is an important and recognizable part of their public image; it is not a list of every celebrity who has shaved their head at some point in their life.

- Andre Agassi, American tennis player[14]

- Kurt Angle, American professional wrestler and Olympic athlete[15]

- "Stone Cold" Steve Austin, American professional wrestler[16]

- Charles Barkley, American basketball player[17]

- David Bateson, English actor[18]

- Jeff Bezos, American businessman[19]

- Dee Dee Bridgewater, American singer[20]

- Kobe Bryant, American basketball player[21]

- Yul Brynner, Russian-American actor[22]

- Yura Borisov, Russian actor[23]

- Bill Burr, American comedian[24]

- Dave Chappelle, American comedian[25]

- Michael Chiklis, American actor[26]

- Phil Collins, English musician[27]

- Common, American rapper[28]

- Billy Corgan, American singer and musician[29]

- Terry Crews, American actor[30]

- Chris Daughtry, American musician[31]

- Vin Diesel, American actor[32]

- Taye Diggs, American actor[33]

- Domenico Dolce, Italian fashion designer[34]

- Anthony Fantano, American music critic[35]

- George Foreman, American boxer[36]

- Tyson Fury, English boxer[37]

- Peter Gabriel, English musician[38]

- Peter Garrett, Australian musician, activist, and politician[39]

- Tyrese Gibson, American actor[40]

- Bill Goldberg, American professional wrestler[41]

- Pep Guardiola, Spanish soccer manager[42]

- Roberto Guilherme, Brazilian actor and comedian[43]

- Rob Halford, English singer[44]

- Rick Harrison, American businessman[45]

- Steve Harvey, American television host[46]

- Phil Heath, American bodybuilder[47]

- Evander Holyfield, American boxer[48]

- LL Cool J, American rapper and actor[49]

- Samuel L. Jackson, American actor[50][51]

- Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson, American actor and professional wrestler[52]

- Magic Johnson, American basketball player[53]

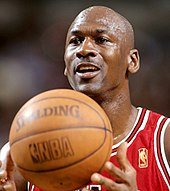

- Michael Jordan, American basketball player[54]

- Keegan-Michael Key, American comedian and actor[55]

- Ben Kingsley, English actor[56]

- Anton LaVey, American author and Satanic Church founder[57]

- John Malkovich, American actor[58]

- Howie Mandel, Canadian comedian and media personality[59]

- Floyd Mayweather, American boxer[60]

- Moby, American musician[61]

- Dean Norris, American actor[62]

- Northernlion, Canadian streamer[63]

- Shaquille O'Neal, American basketball player[64]

- Pitbull, American rapper[65]

- Ving Rhames, American actor[66]

- Flo Rida, American rapper[67]

- Joe Rogan, American podcaster[68]

- Rick Ross, American rapper[69]

- Telly Savalas, American actor[70]

- Tupac Shakur, American rapper[71]

- Brian Shaw, American strongman[72]

- Big Show, American professional wrestler[73]

- Johnny Sins, American pornographic actor[74]

- Skin, English singer[75]

- Chris Slade, Welsh drummer[76]

- Kelly Slater, American surfer[77]

- Jason Statham, English actor[78]

- Patrick Stewart, English actor[79]

- Michael Stipe, American musician[80]

- Corey Stoll, American actor[81]

- Mark Strong, English actor[82]

- Stanley Tucci, American actor[83]

- Dana White, American businessman[84]

- Bruce Willis, American actor[85]

- Zinedine Zidane, French soccer player[86]

Fictional

[edit]In modern fiction, shaved heads are often associated with characters who display a stern and disciplined or hardcore attitude. Examples include characters played by Yul Brynner, Vin Diesel, Samuel L. Jackson, Telly Savalas, Sigourney Weaver, and Bruce Willis, as well as characters such as Agent 47 (whose physical appearance was based on his actor, the aforementioned David Bateson), Mr. Clean, Kratos, Saitama, and Walter White. Baldness is sometimes an important part of these characters' biographies; for example, Saitama wanted to be a superhero and lost all of his hair in exchange for receiving superpowers. Shaved heads are also often associated with villains in fiction,[87] such as Ernst Stavro Blofeld, Colonel Kurtz, Lex Luthor, Thanos, Bullseye, portrayed by Colin Farrell, and Alex Macqueen's version of the Master. A notable exception is Daddy Warbucks.

A goatee, usually of the Van Dyke variety, is often worn to complement the look or add sophistication; this look was popularized in the 1990s by professional wrestler "Stone Cold" Steve Austin. For most of the crime drama series Breaking Bad,[88] Walter White (played by Bryan Cranston) wore a Van Dyke with a shaved head.[89]

In futuristic settings, shaved heads are often associated with bland uniformity, especially in sterile settings such as V for Vendetta and THX 1138.[90] In the 1927 sci-fi film Metropolis, hundreds of extras had their heads shaved to represent the oppressed masses of a future dystopia.

It is less common for female characters to have shaved heads, though some actresses have shaved their heads[91] or used bald caps[92] for roles.

Modern subcultures

[edit]Skinheads

[edit]In the 1960s, some British working-class youths developed the skinhead subculture, whose members were distinguished by short cropped hair (although they did not shave their heads down to the scalp at the time). This look was partly influenced by the Jamaican rude boy style.[93][94] It was not until the skinhead revival in the late 1970s—with the appearance of punk-influenced Oi! skinheads—that many skinheads started shaving their hair right down to the scalp. Head shaving has also appeared in other youth-oriented subcultures such as the hardcore, black metal, metalcore, nu metal, hip hop, techno, and neo-nazi scenes.

Sexuality and gender

[edit]A sexual fetish involving head shaving is called haircut fetishism.

While a shaved head on a man is often seen as a sign of authority and virility[citation needed], a shaved head on a woman typically connotes androgyny, especially when combined with traditionally feminine signifiers.

In the BDSM community, shaving a submissive or slave's head is often used to demonstrate powerlessness or submission to the will of a dominant[why?][citation needed].

Fundraising and support

[edit]Cancer

[edit]

Baldness is perhaps the most famous side effect of the chemotherapy treatment for cancer, and some people shave their heads before undergoing such treatment or after the hair loss starts to become apparent; some people chose to shave their heads in solidarity with cancer sufferers, especially as part of a fundraising effort.

Covhead-19 Challenge

[edit]During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, many countries imposed strict lockdown procedures and actively encouraged members of the public to self-isolate. Many people, particularly men, began to shave their heads during lockdown due to boredom and/or being unable to have their hair cut as barbershops were forced to stay closed.[95] In the UK, a fundraising effort began to support its National Health Service, which suffered from the enormous pressure of the pandemic. The effort was started on Just Giving with a goal of £100,000; it encouraged people to shave their heads whilst also donating money to the NHS and was dubbed the "Covhead-19 Challenge". Various celebrities also took part.[96]

See also

[edit]- Barber – Person who cuts, dresses, grooms, styles and shaves males' hair or beards

- Baldness – Loss of hair from the head or body

- Buzz cut – Variety of very short hairstyle

- Depilation – Body hair removal

- Hair removal – Body hair removal

- List of hairstyles

- Mohawk hairstyle

- Razor – Device to remove body hair

- Shaving – Removal of hair with a razor or other bladed implement

- Skullet – Hairstyle

- Social role of hair

References

[edit]- ^ "'Are You Bald By Choice?'". VICE. 2018-10-31. Retrieved 2025-07-14.

- ^ Geraldine A. Larkin, First You Shave Your Head, Celestial Arts (2001), ISBN 1-58761-009-4

- ^ Naar, Ismaeel (21 August 2018). "Barbers of Mecca and why pilgrims shave their head as Hajj nears its end". Al Arabiya. Dubai, UAE.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Brooks, Beatrice Allard (1922). "The Babylonian Practice of Marking Slaves". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 42: 80–90. doi:10.2307/593615. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 593615.

- ^ Okorocha, Okorie (2016). "Hair and Justice: Sociolegal Significance of Hair in Criminal Justice, Constitutional Law, and Public Policy by Carmen M. Cusack". Journal of Law and Social Deviance. 11: 299.

- ^ Winslow, Donna (1999). "Rites of Passage and Group Bonding in the Canadian Airborne". Armed Forces & Society. 25 (3): 429–457. doi:10.1177/0095327X9902500305. ISSN 0095-327X. S2CID 145604240.

- ^ "Article 87 ... shall be sentenced to flogging, having his head shaven, and one year of exile ..." Archived 2017-08-26 at the Wayback Machine, The Islamic Penal Code of the Islamic Republic of Iran

- ^ Richard J. Evans (2006). The Third Reich in Power. Penguin Books. p. 540. ISBN 978-0-14-100976-6.

- ^ "Shaved Heads and Marked Bodies: Representations From Cultures of Trauma" Kristine Stiles, Duke University (1993) Duke.edu

- ^ ""An Ugly Carnival", The Guardian". Theguardian.com. 30 May 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ "Shorn Women: Gender and Punishment in Liberation France", ISBN 978-1-85973-584-8

- ^ "Ryssän heilat ja pikku-Iivanat" (in Finnish)

- ^ "John Travolta proudly debuts bald head on red carpet after years of wearing wigs". Metro News. 27 January 2019.

- ^ "Andre Agassi Wants Dudes to Embrace Being Bald". Yahoo!. 1 September 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Robinson, Jon (9 September 2008). "The Gamer Interview: Kurt Angle comes clean". ESPN.com. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Stone Cold Steve Austin reveals the key battle that defined him". NewsComAu. 16 May 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (5 May 1993). "Beyond the Fringe: The Boldly Bald". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Langton, Chris (10 April 2017). "Hitman: 15 Awesome Things You Didn't Know About Agent 47". TheGamer. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Sophie; Maloney, Tom; Metcalf, Tom (14 April 2020). "The global economy is crumbling—and Jeff Bezos is $24 billion richer". Fortune. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Dee Dee Bridgewater channels Billie Holiday". Los Angeles Times. 15 March 2010.

- ^ "Kobe Bryant shaved his head to replicate Michael Jordan because of Adidas". TalkBasket.net. 27 February 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Men who look better with a shaved head". The Telegraph. 18 January 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Meet Yura Borisov, the famous-in-Russia thug with a heart from 'Anora'". Los Angeles Times. 26 November 2024.

- ^ Price, Robert (15 November 2016). "Bald Comic Bill Burr Offers Funny, Inspirational, No-BS Advice to a Balding 19-Year-Old (With Audio Clip)". Hair Loss Daily. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Zinoman, Jason (15 August 2013). "A Comic Quits Quitting". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Kate (20 February 2009). "Did Greasepaint Send Michael Chiklis Bald?". The Belgravia Centre. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Wolmuth, Roger (8 July 1985). "Short, Pudgy and Bald, All Phil Collins Produces Is Hits". PEOPLE.com.

- ^ "Common Rates Oprah, Halloween, and Being Produced by Kanye West | Over/Under". YouTube. 18 October 2016.

- ^ Basner, Dave (17 March 2017). "10 Things You Might Not Know about Birthday Boy Billy Corgan". IHeart Radio. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Boucher, Vincent (13 October 2018). "Hollywood's New Power Move: Going "Full Bald"". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "See What Chris Daughtry Looked Like with Hair!". Toofab. 7 November 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Matthews, Stephen (16 September 2017). "Is this why Vin Diesel has sex appeal? Bald men more masculine, says study". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Lewinski, John Scott (23 October 2015). "4 Guys Who Went Bald Before 30 Tell You Why It Doesn't Matter". Men's Health. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Marriott, Hannah (21 March 2015). "Dolce and Gabbana are unafraid of spats, but baby spat divides fans". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "I'm Bald". YouTube. 6 July 2022.

- ^ "Shaved Tyson heads for Foreman". 9 July 1991.

- ^ Richard (6 April 2020). "The Bald Icons: Who is Tyson Fury?". The Bald Brothers. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel: What a Difference Two Decades Make". GenesisFan. 28 August 2012. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Essays". Retrieved 22 September 2025.

- ^ https://facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=3738115869549315&id=199633956730875&set=a.210952398932364 [bare URL]

- ^ "We need to talk about how weird it is seeing WWE legend Goldberg with a full head of hair". 12 September 2024.

- ^ "The hairy reality of balding sportsmen – from Tiger Woods to Gareth Bale". The Telegraph. 22 March 2017.

- ^ "Actor Roberto Guilherme, who played Sergeant Pincel in Os Trapalhões, dies of cancer". O Maringá. 10 November 2022.

- ^ "When rock stars go bald". NME. 12 March 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "Micro Touch One as Seen on TV Safety Razor Commercial Featuring Pawn Stars Rick Harrison". YouTube. 19 December 2013.

- ^ "Why Steve went bald… || STEVE HARVEY". YouTube. 31 August 2016.

- ^ Phil Heath on Instagram: "The attack of the bald heads lol. Always fun hanging with these guys."

- ^ Berger, Phil (14 April 1991). "BOXING; Holyfield: Looking for Respect". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "CBS Sick Of Paying For Bald LL COOL J's Haircuts: EXCLUSIVE". Naughty Gossip. 14 December 2017. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Lee, Chris (1 July 2016). "Samuel L. Jackson's Hair Is His Best Co-Star". GQ. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Abramovitch, Seth (9 January 2019). "120 Movies, $13 Billion in Box Office: How Samuel L. Jackson Became Hollywood's Most Bankable Star". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Bryant, Kenzie (3 April 2017). "Dwayne "The Rock" Johnson Explains Why He's Bald". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Martinez, Jose; Warner, Ralph (7 November 2013). "20 Things You Didn't Know About Magic Johnson". Complex. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Gaines, Cork (17 April 2020). "Michael Jordan once turned down a huge endorsement deal because he didn't like the product's name and another one because he was going bald". Business Insider. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Smith, Zadie (16 February 2015). "Key and Peele's Comedy Partnership". The New Yorker. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Steele, Francesca (19 April 2014). "Ferdinand Kingsley interview: 'Yeah, but mum's dad was totally bald too!'". Spectator. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Gambacorta, David (12 January 2020). "Satan, the FBI, the Mob—and the Forgotten Plot to Kill Ted Kennedy". POLITICO. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "John Malkovich: 'I had a lot of violence growing up, but so what?'". TheGuardian.com. 21 May 2020.

- ^ "Howie Mandel Talks About Embracing His Iconic Look: "I Love Turtles"". 11 September 2023.

- ^ Dator, James (16 May 2016). "Floyd Mayweather, who has no hair, spends up to $3,000 a week on haircuts". SBNation.com.

- ^ Meadley, Phil (26 October 2006). "Moby: how rave culture made him lose his hair". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2022-05-09. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Schilling, Mary Kaye (11 August 2013). "Dean Norris on the Breaking Bad Premiere, Hank's Machismo, and Bryan Cranston's Overachiever E-mails". Vulture. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Lee, Jonathan (8 April 2021). "Streamer shares 'genius' response to troll who shamed him for being bald: 'Here's what you do'". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ Boren, Cindy (4 March 2020). "Shaq has a hilarious hairline after losing a bet to Dwyane Wade". Washington Post. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Oswald, Anjelica (5 February 2019). "John Travolta opened up about embracing his baldness, and says Pitbull convinced him to go for it". Insider. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Bibby, Patricia (10 July 1996). "Ving Rhames Found It Easy To Bulk Up For Role". www.spokesman.com. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Trent (21 September 2011). "Flo Rida Goes Bald for His Birthday Party in Miami". PopCrush. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Podcast Page (24 June 2016). "Joe Rogan on being bald". YouTube. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Rick Ross Shuts Down Rumors That He Wears a Lace-Front Wig". HNHH. 4 April 2018.

- ^ ROBERTS, VIDA (26 October 1995). "A Clean Pate Good and bald: It's a sign of the times and maybe a sign of much more as men move beyond hair". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 9 June 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Jada Pinkett Smith Says Tupac Shakur Had Alopecia: 'He Just Wouldn't Talk About It' (Exclusive)".

- ^ Strongmen Read Mean Comments|World's Strongest Man - YouTube

- ^ Parsons, Jim (15 June 2018). "Other Superstars Who Shaved Their Heads Before Baron Corbin". TheSportster. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Q&A || Johnny Sins Vlog #5 || SinsTV, 5 September 2017, retrieved May 24, 2021

- ^ "Home".

- ^ "Interview with CHRIS SLADE".

- ^ Cave, James (4 April 2016). "Going Bald Was The Best Thing To Happen To These Guys' Heads". HuffPost. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Huynh, Mike (24 July 2019). "Jason Statham Is Showing Bald Men How To Look Stylishly Masculine". DMARGE. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Parker, Ryan (24 March 2017). "Patrick Stewart's Tale of Accepting His Baldness Involves a Physical Altercation with a Judo Master". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (2 November 2007). "Interview: Michael Stipe". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Rapkin, Mickey (4 August 2015). "Corey Stoll: Shaving My Head Was a Game Changer". ELLE. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Oakeley, Lucas (27 July 2017). "The many hairstyles of Mark Strong". Esquire Middle East. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Shaw, Gabbi (7 August 2019). "11 celebrities who are now rocking the bald look". Insider. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Geller, Sarah (16 July 2013). "The 100 Most Powerful Bald Men in the World". GQ. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Friedman, Michael (27 March 2015). "Thank You, Bruce Willis, For Making Bald Beautiful". HuffPost. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Will (5 March 2020). "The Bald Icons: Who is Zinedine Zidane?". The Bald Brothers. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Bald Villains: Why Are So Many Bad Guys Bald?". Freebird | The Bald Truth. Retrieved 2024-06-13.

- ^ Sources that refer to Breaking Bad being praised as one of the greatest television shows of all time include:

- Moore, Frazier (18 December 2013). "2013 brought surprises, good and bad, to viewers". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- St. John, Allen (16 September 2013). "Why 'Breaking Bad' Is The Best Show Ever And Why That Matters". Forbes. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- Bianculli, David (23 December 2013). "Great New DVD Box Sets: Blasts From The Past And 'Breaking Bad'". NPR. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- "2013′s 10 Best and Worst TV Shows, From Good 'Breaking Bad' to Bad 'Broke Girls'". Yahoo TV. 19 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- Hickey, Walter (29 September 2013). "Breaking Bad Is The Greatest Show Ever Made". Business Insider. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- Lawson, Richard (13 July 2012). "The Case for 'Breaking Bad' as Television's Best Show". The Wire. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- Ryan, Maureen (11 July 2012). "'Breaking Bad': Five Reasons It's One of TV's All-Time Greats". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ Stahl, Jeremy (27 September 2013). "Gateway Episodes: Breaking Bad". Slate.

- ^ Lucia Bozzola (2014). "THX 1138". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2014-03-01.

- ^ "22 Actresses Who Shaved Their Heads For a Role". Freebird | The Bald Truth. Retrieved 2024-08-19.

- ^ "Christine Taylor - Biography - Movies & TV - NYTimes.com". www.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ Old Skool Jim. Trojan Skinhead Reggae Box Set liner notes. London: Trojan Records. TJETD169.

- ^ Marshall, George (1991). Spirit of '69 – A Skinhead Bible. S.T. Publishing.

- ^ "Why are so many people shaving their heads?"

- ^ "Coronavirus: What is the 'Covhead challenge' and which celebrities have taken part?". The Independent. 30 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2022-05-09.