Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Palate

View on Wikipedia

| Palate | |

|---|---|

Head and neck. | |

Palate exhibiting torus palatinus | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | palatum |

| MeSH | D010159 |

| TA98 | A05.1.01.102 |

| TA2 | 2778 |

| FMA | 54549 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

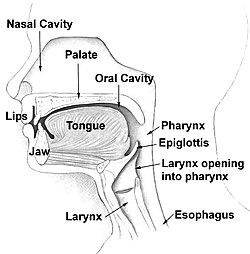

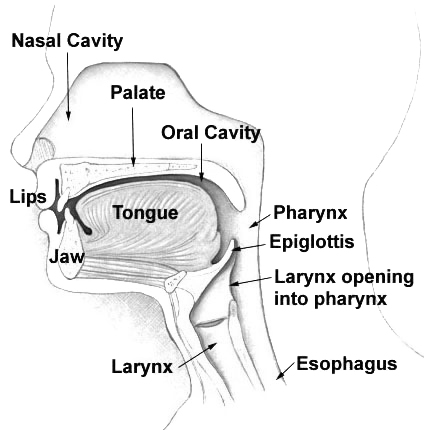

The palate (/ˈpælɪt/) is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.[1] A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly separated. The palate is divided into two parts, the anterior, bony hard palate and the posterior, fleshy soft palate (or velum).[2][3]

Structure

[edit]Innervation

[edit]The maxillary nerve branch of the trigeminal nerve supplies sensory innervation to the palate.

Development

[edit]The hard palate forms before birth.

Variation

[edit]If the fusion is incomplete, a cleft palate results.

Function in humans

[edit]When functioning in conjunction with other parts of the mouth, the palate produces certain sounds, particularly velar, palatal, palatalized, postalveolar, alveolopalatal, and uvular consonants.[4]

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The English synonyms palate and palatum, and also the related adjective palatine (as in palatine bone), are all from the Latin palatum via Old French palat, words that like their English derivatives, refer to the "roof" of the mouth.[5]

The Latin word palatum is of unknown (possibly Etruscan) ultimate origin and served also as a source to the Latin word meaning palace, palatium, from which other senses of palatine and the English word palace derive, and not the other way round.[6]

As the roof of the mouth was once considered the seat of the sense of taste, palate can also refer to this sense itself, as in the phrase "a discriminating palate". By further extension, the flavor of a food (particularly beer or wine) may be called its palate, as when a wine is said to have an oaky palate.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Language

- Vocal tract

- Pallet, palette and pellet, objects whose names are homophonous with palate for many English-speakers

- Palatability

References

[edit]- ^

Wingerd, Bruce D. (1811). The Human Body Concepts of Anatomy and Physiology. Fort Worth: Saunders College Publishing. p. 166. ISBN 0-03-055507-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Wingerd, Bruce D. (1994). The Human Body Concepts of Anatomy and Physiology. Fort Worth: Saunders College Publishing. p. 478. ISBN 0-03-055507-8.

- ^ Goss, Charles Mayo (1966). Gray's Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. p. 1172.

- ^ Goss, Charles Mayo (1966). Gray's Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. p. 1201.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "palate (the entry for)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

palate – late 14c., 'roof of the mouth,' from O.Fr. palat, from L. palatum 'roof of the mouth,' perhaps of Etruscan origin. Popularly considered the seat of taste, hence transferred meaning 'sense of taste' (1520s).

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "palatine (the entry for)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

palatine (adj.) – mid-15c., from M.Fr. palatin (15c.), from M.L. palatinus 'of the palace' (of the Caesars), from L. palatium (see palace). Used in English to mean 'quasi-royal authority.' Reference to the Rhineland state is from c.1580.

Bibliography

[edit]- Saladin, Kenneth (2010). Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 256.

- Thompson, Gale (2005–2006). World of Anatomy and Physiology. Thompson Corporation. pp. Palate (Hard and Soft Palate).

Palate

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Hard Palate

The hard palate forms the anterior two-thirds of the roof of the oral cavity, serving as a rigid divider between the oral and nasal cavities. It is composed of the palatine processes of the maxilla anteriorly and the horizontal plates of the palatine bones posteriorly, which fuse along the midline to create a stable bony framework. This bony structure is covered inferiorly by stratified squamous epithelium and a thick submucosa containing numerous mucous glands that contribute to lubrication and protection of the oral surface.[4] Key anatomical landmarks on the hard palate include the incisive foramen, located anteriorly in the midline just posterior to the central incisors, which transmits the nasopalatine nerve and vessels. Transverse palatine ridges, or rugae palatinae, appear as irregular mucosal folds on the anterior portion, aiding in the manipulation of food within the mouth. The palatine raphe runs as a midline ridge along the fused bony plates, marking the line of embryonic fusion. Posteriorly, the hard palate transitions to the soft palate at its boundary.[4] The blood supply to the hard palate is primarily provided by the greater palatine artery, a branch of the maxillary artery, which emerges from the greater palatine foramen and courses anteriorly; the lesser palatine arteries supply the posterior aspects. Venous drainage occurs via the pterygoid venous plexus. Lymphatic drainage from the hard palate proceeds to the retropharyngeal and deep cervical lymph nodes.[4] In adults, the hard palate measures an average length of approximately 48-50 mm from the incisive papilla to the posterior border, e.g., 48.8 mm in a Saudi population study, with width varying by sex—typically around 36 mm, slightly wider in males (e.g., 36.4 mm vs. 35.9 mm in a Saudi population study)—reflecting sexual dimorphism in craniofacial morphology.[5][4]Soft Palate

The soft palate, also known as the velum or muscular palate, is the flexible posterior continuation of the hard palate, forming the roof of the oral cavity and floor of the nasopharynx. It consists of a fibromuscular structure comprising a thin, firm palatine aponeurosis that serves as the tendonous framework, into which five pairs of muscles are embedded: the tensor veli palatini, levator veli palatini, musculus uvulae, palatoglossus, and palatopharyngeus.[4] This aponeurosis is continuous anteriorly with the periosteum of the hard palate and posteriorly fans out to form the bulk of the soft palate.[6] The entire structure is covered by mucosa; the oral surface features non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium containing minor salivary glands, while the nasal surface transitions to pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium continuous with the nasopharynx.[7][6] The uvula is a conical, midline projection extending from the posterior free border of the soft palate, formed primarily by the musculus uvulae muscle encased in connective tissue and covered by mucosa.[4] It measures approximately 1-1.5 cm in length in adults and contributes to the soft palate's tapered posterior margin.[6] Anteriorly, the soft palate attaches to the posterior edge of the hard palate via the palatine aponeurosis, which anchors to the posterior border of the palatine bone. Laterally, it blends with the pharyngeal walls through fibrous connections, and posteriorly, it connects to the tongue and pharynx via the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches formed by the respective muscles.[4][6] The arterial blood supply to the soft palate is provided by the lesser palatine arteries, which are terminal branches of the descending palatine artery originating from the maxillary artery, and the ascending palatine artery, a branch of the facial artery, which ascends along the lateral pharyngeal wall to anastomose with branches within the palate. Venous drainage occurs primarily via the pharyngeal venous plexus, which communicates with the pterygoid venous plexus.[4][8] Histologically, the soft palate contains skeletal muscle fibers from the five embedded muscles, interspersed with dense fibrous connective tissue in the aponeurosis that includes elastic fibers contributing to its resilience. The mucosal layer exhibits a lamina propria rich in lymphoid tissue, particularly on the nasal side, supporting its epithelial covering.[7][6] The soft palate shares sensory innervation overlap with the hard palate through the lesser palatine nerves, branches of the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve.[4]Innervation

The sensory innervation of the palate primarily arises from branches of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V), with contributions from the glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX) in the posterior regions. The hard palate receives sensory supply from the greater palatine nerve, a branch of the maxillary nerve (V2), which innervates the mucosa of the posterior two-thirds of the hard palate. The anterior hard palate is innervated by the nasopalatine nerve, another branch of V2, entering through the incisive foramen to supply the region behind the incisors. These V2 branches emerge from the trigeminal ganglion in the trigeminal cave, pass through the foramen rotundum into the pterygopalatine fossa, and distribute via the pterygopalatine nerves. The soft palate is mainly supplied by the lesser palatine nerve, also from V2, which descends through the lesser palatine canal to provide sensory fibers to the soft palate mucosa. The posterior soft palate and fauces receive additional sensory innervation from the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), which conveys general sensation from the pharyngeal mucosa and oropharynx.[9][10][11] Motor innervation to the palate is provided by the pharyngeal plexus, formed primarily by branches of the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) with contributions from the cranial root of the accessory nerve (XI), supplying most muscles of the soft palate such as the levator veli palatini, palatoglossus, and palatopharyngeus. An exception is the tensor veli palatini muscle, which receives motor supply from the mandibular nerve (V3) via its branch to the medial pterygoid muscle; V3 fibers originate from the trigeminal ganglion, exit via the foramen ovale, and travel in the infratemporal fossa before branching. The pharyngeal plexus forms in the pharyngeal wall, integrating vagal motor fibers from the nucleus ambiguus with sympathetic components, to distribute to the soft palate musculature.[4][12][13][14] Autonomic innervation to the palate regulates glandular secretion and vasomotor functions. Parasympathetic fibers reach the palate via the lesser palatine nerves, originating from the pterygopalatine ganglion, where preganglionic fibers from the facial nerve (VII) via the greater petrosal nerve synapse; these postganglionic fibers stimulate seromucous gland secretion in the soft and hard palate mucosa. Sympathetic innervation derives from the superior cervical ganglion, traveling through the pharyngeal plexus along carotid branches to provide vasomotor control and minor glandular influence in the palatal tissues.[15][16][17][14] Clinically, the shared sensory pathways via V2 branches can lead to referred pain patterns, such as maxillary sinus pathology manifesting as palatal discomfort due to convergent innervation in the trigeminal ganglion.[10][18]Development and Variation

Embryological Development

The embryological development of the palate begins early in gestation, originating from distinct facial prominences derived primarily from neural crest cells that migrate into the developing face by the fourth week of human embryonic development. These neural crest cells contribute to the mesenchyme of the frontonasal prominence and the paired maxillary processes of the first branchial arch.[19][20] The primary palate, which forms the anterior portion including the premaxilla and nasal floor, arises from the frontonasal prominence through the fusion of the median nasal prominences around weeks 6 to 7, establishing the initial separation between the oral and nasal cavities.[19][20] The secondary palate, comprising the majority of the mature structure including the hard and soft palate, develops from the lateral palatal shelves that protrude from the maxillary processes. Initially positioned vertically alongside the tongue, these shelves elevate to a horizontal orientation around weeks 7 to 8, a process triggered by tongue depression and changes in the extracellular matrix, such as increased hyaluronic acid accumulation and activity of proteases like ADAMTS.[19][20] Following elevation, the shelves grow medially and fuse with each other, the primary palate anteriorly, and the nasal septum posteriorly between weeks 9 and 12, completing the partition of the oral and nasal cavities.[19][20] Ossification of the hard palate commences around week 8, progressing posteriorly from the maxilla and palatine bones.[19] Molecular regulation is essential for these coordinated events, with transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling, particularly TGF-β3, promoting palatal shelf growth through epithelial-mesenchymal interactions and upregulation of genes like Fgf10 and Bmp4 in the mesenchyme.[21] Genes such as IRF6 and MSX1 play critical roles in shelf fusion, where MSX1 supports anterior growth and IRF6 facilitates medial edge epithelium remodeling.[19][21] Full fusion is typically achieved by week 12, though the musculature of the soft palate differentiates later from myogenic cells originating in the occipital somites that migrate into the branchial arches.[19][20] Disruptions in these processes, such as impaired shelf elevation or fusion, can result in congenital anomalies like cleft palate, with incidence varying by ethnicity (e.g., higher in Asian and Native American populations).[19]Anatomical Variations

The human palate exhibits a range of anatomical variations in size, shape, and structure that occur within normal populations, influenced by genetic, ethnic, and developmental factors. One common variation in the hard palate is the presence of torus palatinus, a benign bony prominence along the midline raphe, affecting approximately 20-30% of adults globally.[22] This exostosis is more prevalent in individuals of Asian descent, with rates reaching up to 34.7% in East Asian populations compared to 24.9% in Europeans.[23] Another shape variation is the high-arched palate, characterized by an elevated and narrow vault, which shows subtle differences across ethnic groups in otherwise healthy individuals, though not as a primary ethnic marker.[24] Studies indicate that hard palate dimensions are generally larger in males than females, with males exhibiting greater transverse dimensions and increased posterior height during adulthood.[25] With advancing age, the palatal vault height often increases, particularly in males, while female palates show more consistent shape changes from adolescence onward.[26] Racial variations include differences in palatal depth and width; for instance, palates in African populations are typically deeper and wider compared to those in Caucasian populations, aiding in forensic identification of ancestry through measurements of palatal dimensions.[27] Variations in the soft palate include the bifid uvula, a split or notched uvula occurring in 1-10% of individuals, often discovered incidentally and remaining asymptomatic without functional impairment.[28][29] An elongated soft palate represents another variant, where the structure extends further posteriorly, potentially increasing susceptibility to airway obstruction during sleep, though it is a normal anatomical difference rather than a disorder.[30] In the hard palate, the midline raphe may appear fissured in some individuals, and palatal rugae—transverse ridges aiding in food manipulation—can vary in number or be partially absent, reflecting individual morphometric diversity without clinical consequence. From an evolutionary perspective, the human palate shows comparative thickening relative to other mammals, adapted for enhanced mastication through broader contact surfaces, but its unique positioning and flexibility in Homo sapiens support articulate speech production, distinguishing it from primarily mastication-focused structures in other primates.[31] These variations, including subtle adaptations in innervation to accommodate shape differences, underscore the palate's plasticity across populations.[24]Functions

In Swallowing and Respiration

The soft palate plays a critical biomechanical role in swallowing by elevating to close the velopharyngeal port, thereby preventing the reflux of the bolus into the nasopharynx. This elevation is primarily achieved through contraction of the levator veli palatini muscle, which lifts the soft palate against the posterior pharyngeal wall to form a tight seal during the pharyngeal phase of deglutition.[32][33] Concurrently, the tensor veli palatini muscle tenses the soft palate, providing structural support and facilitating efficient closure.[34] In the oral preparatory and oral transit phases, the hard palate's transverse rugae assist in bolus containment and propulsion by creating friction against the tongue as it squeezes the food bolus posteriorly.[35] The coordination of palatal movements during swallowing is integrated with pharyngeal muscles through the pharyngeal plexus, which provides sensory and motor innervation to synchronize the elevation of the soft palate with pharyngeal contraction and laryngeal elevation.[36] Velopharyngeal closure generates positive intrapharyngeal pressure to isolate the airway from the digestive tract and propel the bolus toward the esophagus while minimizing aspiration risk.[37] In respiration, the soft palate maintains an open position at rest, ensuring patency between the nasopharynx and oropharynx to facilitate unobstructed nasal airflow.[38] During nasal breathing, the soft palate remains lowered and in contact with the posterior tongue, partitioning airflow to prevent oral cavity involvement and supporting efficient ventilation.[39] Age-related changes, including reduced muscle tone and slower contraction speed in the levator veli palatini, lead to weaker velopharyngeal closure in older adults, thereby increasing the risk of incomplete sealing and aspiration during swallowing.[40]In Speech and Other Roles

The soft palate plays a crucial role in speech production by dynamically separating the oral and nasal cavities to modulate airflow and resonance. During the articulation of oral sounds, such as velar consonants like /k/ and /g/, the soft palate elevates to close the velopharyngeal port, directing air exclusively through the mouth and preventing nasal resonance.[6] In contrast, for nasal sounds like /m/ and /n/, the soft palate lowers, opening the velopharyngeal port to allow air to resonate in the nasal cavity, producing the characteristic nasal timbre.[4] Incomplete closure of this port, known as velopharyngeal insufficiency, can result in hypernasality, where vowels and voiced consonants acquire excessive nasal quality, often compromising speech intelligibility.[41] The hard palate contributes to sensory aspects of speech and oral interactions through tactile feedback, aiding in the precise positioning of the tongue during articulation. Innervated by branches of the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V), including the greater and lesser palatine nerves, the hard palate provides mechanosensory input that enhances bolus manipulation and phonetic accuracy during eating and speaking.[42] Additionally, the palate supports a minor gustatory function, with taste buds in the palatal region innervated by the greater superficial petrosal nerve, a branch of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), contributing to flavor perception primarily in the posterior oral cavity.[43] Beyond phonation, the palate fulfills other sensory and protective roles. Its minor salivary glands secrete mucus that lubricates the oral mucosa and facilitates evaporative cooling, supporting localized thermoregulation during increased metabolic activity or environmental heat.[44] The palate also serves as a structural barrier, preventing the spread of oral pathogens to the nasal cavity and reducing infection risk in the upper respiratory tract.[4] Acoustically, variations in palate shape influence speech characteristics, particularly vowel production. A more domed or high-arched palate can alter the oral cavity's geometry, shifting vowel formants—resonant frequencies that define timbre—and contributing to distinct accents or dialects, such as those with elevated second formant frequencies in certain frontal vowels.[45] Evolutionarily, the human palate exhibits adaptations that enhance articulate speech compared to other primates. Unlike the shorter, less flexible palates in chimpanzees and other apes, which limit precise velar articulation and nasal-oral distinction, the descended and elongated human palate, coupled with a lowered larynx, enables a broader range of phonetic contrasts essential for complex language.[46]Clinical Aspects

Congenital Disorders

Congenital disorders of the palate primarily involve developmental malformations that arise during embryogenesis, with cleft palate being the most common. These conditions result from disruptions in the formation and fusion of palatal structures, leading to gaps in the roof of the mouth that can affect feeding, speech, and ear health. Clefts are classified into types such as cleft lip with or without cleft palate (CL/P) and isolated cleft palate (CP), where the latter involves only the secondary palate without lip involvement.[47][48] The global incidence of orofacial clefts, encompassing both CL/P and CP, is approximately 1 in 700 live births, though rates vary by region and ethnicity. Isolated CP occurs at a lower rate of about 1 in 1,600 to 2,500 births. Prevalence is higher among Asian and Native American populations compared to African or Caucasian groups, with reported rates up to 1.8 per 1,000 in some Asian cohorts. Epidemiologically, isolated CP shows a female predominance, while CL/P is more common in males; overall, about 30% of cleft cases are syndromic, associated with genetic syndromes, whereas the majority are non-syndromic.[49][47][50][51][52] The etiology of cleft palate is multifactorial, involving genetic predispositions and environmental influences. Genetic factors include mutations in genes such as IRF6, which is implicated in Van der Woude syndrome, a common syndromic cause of cleft lip and palate. Other genes like MSX1 contribute to isolated CP through disruptions in palatal shelf development. Environmental risks include maternal smoking during pregnancy, which increases the odds of CL/P by 1.2- to 1.5-fold, and folate deficiency, where inadequate periconceptional folic acid intake elevates risk by up to 20%. These factors interact with genetic susceptibility, often leading to incomplete penetrance.[53][54][55][56] Beyond isolated clefts, other congenital anomalies frequently involve the palate. Pierre Robin sequence is characterized by micrognathia (small lower jaw), glossoptosis (posterior tongue displacement), and U-shaped cleft palate, often resulting from mechanical constraints on palatal shelf elevation in utero. Stickler syndrome, caused by mutations in collagen genes like COL2A1, is associated with cleft palate in up to 60% of cases, alongside ocular and skeletal features. These conditions highlight the interplay between craniofacial development and connective tissue integrity.[48][57][58] Embryologically, cleft palate stems from failure of the palatal shelves—outgrowths from the maxillary processes—to elevate from a vertical to horizontal position or fuse midline around weeks 6-9 of gestation. This process requires coordinated mesenchymal proliferation, apoptosis of the midline epithelial seam, and extracellular matrix remodeling; disruptions, such as delayed shelf elevation due to micrognathia, prevent proper closure. Diagnosis typically occurs via prenatal ultrasound, which detects clefts in 20-50% of cases depending on severity, or through postnatal physical examination revealing the oral defect.[59][60][61] Associated risks include feeding difficulties from poor suction and nasal regurgitation, recurrent ear infections due to Eustachian tube dysfunction causing middle ear effusion, and speech delays from velopharyngeal insufficiency. These complications can lead to growth faltering and hearing loss if unaddressed, underscoring the need for multidisciplinary early intervention. Surgical correction, often involving palatoplasty around 9-12 months, aims to restore function but is tailored to individual anatomy.[62][48][63]Acquired Conditions and Treatments

Acquired conditions affecting the palate often arise from environmental or postnatal factors, including trauma, infections, neoplasms, and neurological impairments, leading to structural or functional disruptions such as pain, swallowing difficulties, and speech alterations.[64][65] Trauma to the palate, typically resulting from high-energy maxillofacial injuries like motor vehicle accidents or falls, can cause palatal fractures that compromise the structural integrity of the hard or soft palate. These fractures may present with ecchymosis, mobility, or gaps in the palatal vault, potentially leading to acquired clefts if untreated. Treatment generally involves closed reduction with wiring or acrylic splints for stabilization, or open reduction with internal fixation using titanium plates for more complex, comminuted fractures, aiming to restore occlusion and prevent long-term complications like malunion.[66][67][68] Infections such as oral candidiasis can involve the palate, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, manifesting as white plaques or erythematous lesions that erode the mucosal surface and cause discomfort during eating or speaking. Neoplasms, including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), represent a significant acquired threat to the palate, with SCC being the most common malignancy affecting both hard and soft palatal tissues. Risk factors for palatal SCC include tobacco use (smoked or smokeless), alcohol consumption, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, particularly HPV-16, which synergistically increases carcinogenic potential. The prevalence of these neoplasms is rising in aging populations due to cumulative exposure to risk factors and improved diagnostic awareness.[69][70][71] Neurological conditions can induce velopharyngeal incompetence, where inadequate closure of the velopharyngeal port during speech or swallowing results in hypernasality and nasal regurgitation. Post-stroke events may damage cranial nerves innervating the palate, leading to flaccid paralysis and impaired elevation of the soft palate. Similarly, myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune neuromuscular disorder, often affects bulbar muscles, causing velopharyngeal dysfunction in up to 50% of patients with bulbar symptoms and producing perceptual hypernasality.[41][72][73] Therapeutic approaches for these acquired conditions are multidisciplinary, tailored to the underlying cause and extent of involvement. Surgical interventions, such as palatoplasty for defects resulting from trauma, infection, or neoplasm resection, involve tissue flaps to close acquired clefts or fistulas, often combined with prosthetics like obturators to seal the velopharyngeal gap and improve separation of oral and nasal cavities. Radiotherapy is a cornerstone for palatal SCC, typically delivered as intensity-modulated radiation therapy to target tumors while minimizing damage to surrounding tissues, either alone or post-surgery. Speech therapy addresses functional deficits, focusing on compensatory techniques to reduce hypernasality and enhance articulation in cases of velopharyngeal incompetence.[65][74][75] Outcomes of these treatments vary but demonstrate substantial functional recovery with appropriate care; for instance, surgical repair of acquired palatal defects achieves good clinical results in approximately 91% of cases through multidisciplinary management, including flap techniques. Complications, such as oronasal fistulas, occur in 4-45% of repairs depending on defect size and vascularity, with rates around 5-10% in optimized settings using local flaps. Congenital predispositions may occasionally heighten susceptibility to acquired injuries, but postnatal interventions remain the focus.[76][77] Recent advances in tissue engineering offer promising regenerative options for palatal repair, particularly through stem cell-based therapies. As of 2025, clinical trials utilizing dental mesenchymal stem cells for orofacial tissue regeneration, including palate defects from acquired causes like trauma or neoplasm, have shown potential in promoting bone and soft tissue healing with reduced scarring, building on preclinical models of cleft-related regeneration. These approaches, often combined with scaffolds or hydrogels, aim to enhance endogenous repair mechanisms and are under evaluation in phase I/II studies for safety and efficacy.[78][79]History

Anatomical Discoveries

The understanding of the palate's anatomy began in ancient times with early observations of its structure and function. In the 5th century BCE, Hippocrates noted descriptions of facial clefts, such as cleft lip, in his medical writings, recognizing them as congenital anomalies.[80] In the 2nd century CE, Galen advanced this knowledge by describing the anatomy of the soft palate and its involvement in swallowing and voice production, highlighting its role in separating the nasal and oral cavities.[81] During the Renaissance, anatomical studies benefited from direct dissection and illustration. Andreas Vesalius, in his seminal 1543 work De Humani Corporis Fabrica, provided detailed illustrations of the hard and soft palate structures, depicting the bony framework of the hard palate formed by the maxilla and palatine bones, and the muscular composition of the soft palate, correcting earlier misconceptions based on animal dissections.[82] Gabriele Falloppio, in 1561, contributed to the understanding of palatal anatomy, including its muscular structure and related nerves.[83] In the 19th century, connections between palate anatomy and broader human capabilities emerged alongside embryological insights. Wilhelm His, during the 1870s and 1880s, provided detailed embryological descriptions of human development, including the formation of facial structures such as the palate, elucidating aspects of fetal development that create a continuous roof for the oral cavity.[84] The 20th century saw advancements in visualizing palate dynamics, informed by surgical and imaging innovations. George M. Dorrance, in the 1920s, advanced understanding through his push-back surgical technique for cleft palate repair, which revealed the functional anatomy of the soft palate's levator veli palatini muscle in achieving velopharyngeal closure.[85] Radiographic studies in the 1930s, using lateral cephalometric X-rays, first visualized velar movement during swallowing and speech, demonstrating the soft palate's elevation and the role of its tensor and levator muscles in coordination with pharyngeal structures.[86] In modern times, imaging and genetic research have deepened anatomical insights. Since the 1990s, MRI and 3D imaging techniques have enabled non-invasive study of palate development and movement, revealing dynamic interactions between the hard and soft palate during fetal growth and postnatal function.[4] Genetic studies in the 2000s identified key links to palate anomalies, such as the 2004 discovery of variants in the IRF6 gene associated with nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate, accounting for approximately 12% of the genetic risk and tripling recurrence odds in affected families.[87]Etymology

The term "palate" derives from the Latin palatum, meaning "roof of the mouth" or "vault," which entered Middle English around the late 14th century via Old French palat.[88] This Latin word, of uncertain ultimate origin but possibly Etruscan, initially denoted the anatomical structure separating the oral and nasal cavities and later extended metaphorically to the sense of taste, as seen in related terms like "palatable".[89] In ancient Greek, the palate was referred to as ouraniskos, a diminutive of ouranos meaning "heaven" or "sky," evoking the vaulted shape of the mouth's roof.[90] Specific subterms emerged in medical nomenclature over centuries. The "hard palate," or palatum durum in Latin (with durum signifying "hard" due to its bony composition), appeared in English anatomical descriptions by the late 18th century, though Latin usage predates this in Renaissance texts.[91] The "soft palate," known as velum palatinum or simply velum, draws from Latin velum meaning "veil," "sail," or "covering," reflecting its flexible, muscular nature; this designation became common in European anatomy from the 16th century onward.[6] The "uvula," the conical projection from the soft palate's posterior edge, originates from Late Latin uvula, a diminutive of uva ("grape"), coined in medieval Latin to describe its grapelike shape; the Roman physician Celsus (1st century CE) referred to it simply as uva in his De Medicina.[92][93] Modern anatomical terminology standardized these terms through the Basle Nomina Anatomica (BNA) of 1895, the first international Latin nomenclature adopted by anatomists, which formalized palatum durum for the anterior bony portion and palatum molle for the posterior muscular part; this system influenced subsequent revisions, including the current Terminologia Anatomica endorsed by the Federative International Programme on Anatomical Terminology (FIPAT).[94][95] In some languages, palate-related terms retain connections to sensory or architectural concepts. For instance, French palais serves dual purposes, denoting both the anatomical palate and a grand palace, stemming from Vulgar Latin palātium—an alteration of palātum influenced by palātium ("palace," originally referring to Rome's Palatine Hill).[96]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/palais