Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Paleolithic dog

View on Wikipedia

Purported remains of Paleolithic dogs have been reported from several European archaeological sites dating to over 30,000 years ago. Their status as domesticated is highly controversial, with some authors suggesting them to be the ancestors of the domestic dog or an extinct, morphologically and genetically divergent wolf population.

Taxonomy

[edit]One authority has classified the Paleolithic dog as Canis cf. familiaris[1] (where cf. is a Latin term meaning uncertain, as in Canis believed to be familiaris). Previously in 1969, a study of ancient mammoth-bone dwellings at the Mezine paleolithic site in the Chernihiv region, Ukraine uncovered 3 possibly domesticated "short-faced wolves".[2][3] The specimens were classified as Canis lupus domesticus (domesticated wolf).[3][4]

Naming

[edit]In 2002, a study looked at 2 fossil skulls of large canids dated at 16,945 years before present (YBP) that had been found buried 2 metres and 7 metres from what was once a mammoth-bone hut at the Upper Paleolithic site of Eliseevichi-1 in the Bryansk region of central Russia, and using an accepted morphologically based definition of domestication declared them to be "Ice Age dogs".[5] In 2009, another study looked at these 2 early dog skulls in comparison to other much earlier but morphologically similar fossil skulls that had been found across Europe and concluded that the earlier specimens were "Paleolithic dogs", which were morphologically and genetically distinct from Pleistocene wolves that lived in Europe at that time.[6]

Description

[edit]

The Paleolithic dog was smaller than the Pleistocene wolf (Canis cf. lupus)[1] and the extant grey wolf (Canis lupus), with a skull size that indicates a dog similar in size to the modern large dog breeds. The Paleolithic dog had a mean body mass of 36–37 kg (79–82 lb) compared to Pleistocene wolf 42–44 kg (93–97 lb) and recent European wolf 41–42 kg (90–93 lb).[6]

The earliest sign of domestication in dogs was thought to be the neotenization of skull morphology[7][8][9] and the shortening of snout length. This leads to tooth crowding, a reduction in tooth size and the number of teeth,[7][10] which has been attributed to the strong selection for reduced aggression.[7][8]

Compared with the Pleistocene and modern wolves, the Paleolithic dog had a shorter skull length, a shorter viscerocranium (face) length, and a wider snout.[6] It had a wider palate and wider braincase,[6][9] relatively short and massive jaws, and a shorter carnassial length but these were larger than the modern dog and closer to those of the wolf. The mandible of the Paleolithic dog was more massive compared to the elongated mandible of the wolves and had more crowded premolars, and a hook-like extension in the caudal border of the coronoid process of the mandible. The snout width was greater than those of both the Pleistocene and modern wolves, and implies well-developed carnassials driven by powerful jaws. In two morphometric analyses, the nearest dog skull-shape that was similar to the Paleolithic dog was that of the Central Asian Shepherd Dog.[6]

Diet

[edit]In 2015, a study of bone collagen taken from a number of species found at the 30,000 YBP mammoth-hut site of Predmosti in the Czech Republic indicated that the Pleistocene wolf ate horse and possibly mammoth, the Paleolithic dog ate reindeer and muskox, and the humans ate specifically mammoth. The study proposes that the Paleolithic dog's diet had been artificially restricted because it was not a diet similar to the Pleistocene wolf. Some remote Arctic tribal people today restrict the diet of their dogs away from what those people prefer to eat.[1] An analysis of a specimen from the Eliseevichi-1 site on the Russian plain also revealed that the Paleolithic dog ate reindeer.[11]

In 2020, a study of dental microwear on tooth enamel for canine specimens from Predmosti dated 28,500 YBP suggest a higher bone consumption for the proto-dogs compared with wolf specimens. This indicates two morphologically and behaviourally different canine types. The study proposes that the proto-dogs consumed more bone along with other less desirable food scraps within human camps, therefore this may be evidence of early dog domestication.[12]

Archaeological evidence

[edit]- See further Paleoecology of the time

Early specimens

[edit]There are a number of recently discovered specimens which are proposed as being Paleolithic dogs, however their taxonomy is debated. These have been found in either Europe or Siberia and date 40,000–17,000 YBP. They include Hohle Fels in Germany, Goyet Caves in Belgium, Predmosti in the Czech Republic, and four sites in Russia: Razboinichya Cave in the Altai Republic, Kostyonki-8, Ulakhan Sular in the Sakha Republic, and Eliseevichi 1 on the Russian plain. Paw-prints from Chauvet Cave in France dated 26,000 YBP are suggested as being those of a dog, however these have been challenged as being left by a wolf.[13]

| Years BP | Location | Finding |

|---|---|---|

| 40,000–35,000 | Hohle Fels, Schelklingen, Germany | Paleolithic dog |

| 36,500 | Goyet Caves, Mozet, Belgium | Paleolithic dog |

| 33,500 | Razboinichya Cave, Altai Mountains, Central Asia | Paleolithic dog |

| 33,500–26,500 | Kostyonki-Borshchyovo archaeological complex, Voronezh, Russia | Paleolithic dog |

| 31,000 | Predmostí, Moravia, Czech Republic | Paleolithic dog |

| 26,000 | Chauvet Cave, Vallon-Pont-d'Arc, France | Paw-prints |

| 17,200 | Ulakhan Sular, northern Yakutia, Siberia | Paleolithic dog |

| 17,000–16,000 | Eliseevichi-I site, Bryansk Region, Russian Plain, Russia | Paleolithic dog |

There are also a number of later proposed Paleolithic dogs whose taxonomy has not been confirmed. These include a number of specimens from Germany (Kniegrotte, Oelknitz, Teufelsbrucke), Switzerland (Monruz, Kesslerloch, Champre-veyres-Hauterive), as well as Ukraine (Mezin, Mezhirich). A set of specimens dating 15,000–13,500 YBP have been confidently identified as domesticated dogs, based on their morphology and the archaeological sites in which they have been found. These include Spain (Erralla), France (Montespan, Le Morin, Le Closeau, Pont d'Ambon) and Germany (Bonn-Oberkassel). After this period, the remains of domesticated dogs have been identified from archaeological sites across Eurasia.[13]

Possible dog domestication between 15,000 and 40,000 YBP is not clear due to the debate over what the Paleolithic dog specimens represent. This is due to the flexibility of genus Canis morphology, and the close morphological similarities between Canis lupus and Canis familiaris. It is also due to the scarcity of Pleistocene wolf specimens available for analyses and so their morphological variation is unknown. Habitat type, climate, and prey specialization greatly modify the morphological plasticity of grey wolf populations, resulting in a range of morphologically, genetically, and ecologically distinct wolf morphotypes. With no baseline to work from, zooarchaeologists find it difficult to be able to differentiate between the initial indicators of dog domestication and various types of Late Pleistocene wolf ecomorphs, which can lead to the mis-identification of both early dogs and wolves. Additionally, the ongoing prehistoric admixture with local wolf populations during the domestication process may have led to canids that were domesticated in their behavior but wolflike in their morphology. Attempting to identify early tamed wolves, wolfdogs, or proto-dogs through morphological analysis alone may be impossible without the inclusion of genetic analyses.[13]

All specimens

[edit]The table below lists by location and timing in years before present the very early co-location of hominid and wolf specimens, followed by proposed paleolithic dog and then early dog specimens, with the regions in which they had been found color-coded as purple – Western Eurasia, red – Eastern Eurasia and green – Central Eurasia.

| Years BP | Location | Finding |

|---|---|---|

| 400,000 | Boxgrove near Kent, England | Wolf bones in close association with hominid bones. These have been found in Lower Paleolithic sites including Boxgrove (400,000 YBP), Zhoukoudian in North China (300,000 YBP), and Grotte du Lazaret (125,000 YBP) in southern France. "The sites of occupation and hunting activities of humans and wolves must often have overlapped."[14] It is unknown if the co-location was the result of coincidence or a relationship. |

| 300,000 | Zhoukoudian cave system, China | Small, extinct wolf skulls of Canis variabilis. At the site, the small wolf's remains were in close proximity to Peking Man (Homo erectus pekinensis).[15] It is unknown if the co-location was the result of coincidence or a relationship. |

| 125,000 | Grotte du Lazaret, near Nice, France | Wolf skulls appear to have been set at the entrance of each dwelling in a complex of Paleolithic shelters. The excavators speculated that wolves were already incorporated into some aspect of human culture by this early time. A nearby wolf den intruded on the site.[16] In 1997, a study of maternal mDNA indicated that the genetic divergence of dogs from wolves occurred 100,000–135,000 YBP.[17] The Lazaret excavation lends credence to this mDNA study, in addition to indicating that a special relationship existed between wolves and genus Homo other than Homo sapiens, because this date is well before the arrival of Homo sapiens into Europe.[18] In 2018, a study of paternal yDNA indicated that the dog and the modern grey wolf genetically diverged from a common ancestor between 68,000 and 151,000 YBP.[19] |

| 40,000–35,500 | Hohle Fels, Schelklingen, Germany | Canid maxillary fragment. The size of the molars matches those of a wolf, the morphology matches a dog.[20] Proposed as a Paleolithic dog. The figurine Venus of Hohle Fels was discovered in this cave and dated to this time. |

| 36,500 | Goyet Cave, Samson River Valley, Belgium | The "Goyet dog" is proposed as being a Paleolithic dog.[6] The Goyet skull is very similar in shape to that of the Eliseevichi-I dog skulls (16,900 YBP) and to the Epigravettian Mezin 5490 and Mezhirich dog skulls (13,500 BP), which are about 18,000 years younger.[6][21] The dog-like skull was found in a side gallery of the cave, and Palaeolithic artifacts in this system of caves date from the Mousterian, Aurignacian, Gravettian, and Magdalenian, which indicates recurrent occupations of the cave from the Pleniglacial until the Late Glacial.[6] The Goyet dog left no descendants, and its genetic classification is inconclusive because its mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) does not match any living wolf nor dog. It may represent an aborted domestication event or phenotypically and genetically distinct wolves.[22] A genome-wide study of a 35,000 YBP Pleistocene wolf fossil from northern Siberia indicates that the dog and the modern grey wolf genetically diverged from a common ancestor between 27,000 and 40,000 YBP.[23][18] |

| 33,500 | Razboinichya Cave, Altai Mountains, Central Asia (Russia) | The "Altai dog" is proposed as being a Paleolithic dog.[6] The specimens discovered were a dog-like skull, mandibles (both sides) and teeth. The morphological classification, and an initial mDNA analysis, found it to be a dog.[24] A later study of its mDNA was inconclusive, with 2 analyses indicating dog and another 2 indicating wolf. In 2017, two prominent evolutionary biologists reviewed the evidence and supported the Altai dog as being a dog from a lineage that is now extinct and that was derived from a population of small wolves that are also now extinct.[25] |

| 33,500–26,500 | Kostyonki-Borshchyovo archaeological complex, Voronezh, Russia | One left mandible paired with the right maxilla, proposed as a Paleolithic dog.[26] |

| 31,000 | Predmostí, Moravia, Czech Republic | Three dog-like skulls proposed as being Paleolithic dogs.[26] Predmostí is a Gravettian site. The skulls were found in the human burial zone and identified as Palaeolithic dogs, characterized by – compared to wolves – short skulls, short snouts, wide palates and braincases, and even-sized carnassials. Wolf skulls were also found at the site. One dog had been buried with a bone placed carefully in its mouth. The presence of dogs buried with humans at this Gravettian site corroborates the hypothesis that domestication began long before the Late Glacial.[27][28] Further analysis of bone collagen and dental microwear on tooth enamel indicates that these canines had a different diet when compared with wolves (refer under diet).[11][12] |

| 30,800 | Badyarikha River, northern Yakutia, Siberia | Fossil canid skull. The specimen could not be classified as wolf nor Paleolithic dog.[29] |

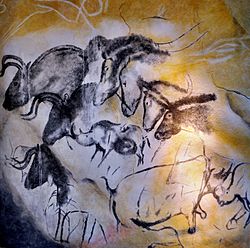

| 26,000 | Chauvet Cave, Vallon-Pont-d'Arc, Ardèche region, France | 50-metre trail of footprints made by a boy of about ten years of age alongside those of a large canid. The size and position of the canid's shortened middle toe in relation to its pads indicates a dog rather than a wolf. The footprints have been dated by soot deposited from the torch the child was carrying. The cave is famous for its cave paintings.[30] A later study using geometric morphometric analysis to compare modern wolf with modern dog tracks proposes that these are wolf tracks.[31] |

| 18,000 | Indigirka, Yakutia, Siberia | Dogor, a canine pup preserved in permafrost and yet to be identified as being a dog or wolf.[32] |

| 17,300–14,100 | Dyuktai Cave, northern Yakutia, Siberia | Large canid remains along with human artefacts.[29] |

| 17,200–16,800 | Ulakhan Sular, northern Yakutia, Siberia | Fossil dog-like skull similar in size to the "Altai dog", proposed as a Paleolithic dog.[29] |

| 17,000–16,000 | Eliseevichi-I site, Bryansk Region, Russian Plain, Russia | Two fossil canine skulls proposed as being a Paleolithic dogs.[6] In 2002, a study looked at the fossil skulls of two large canids that had been found buried 2 metres and 7 metres from what was once a mammoth-bone hut at this Upper Paleolithic site, and using an accepted morphologically based definition of domestication declared them to be "Ice Age dogs". The carbon dating gave a calendar-year age estimate that ranged between 16,945 and 13,905 YBP.[5] The Eliseevichi-1 skull is very similar in shape to the Goyet skull (36,000 BP), the Mezine dog skull (13,500 BP) and Mezhirich dog skull (13,500 BP).[6] In 2013, a study looked at the mDNA sequence for one of these skulls and identified it as Canis lupus familiaris i.e. dog.[22] However, in 2015 a study using three-dimensional geometric morphometric analyses indicated the skull is more likely from a wolf.[33][34] These animals were larger in size than most grey wolves and approach the size of a Great Dane.[35] |

| 16,900 | Afontova Gora-1, Yenisei River, southern Siberia | Fossil dog-like tibia, proposed as a Paleolithic dog. The site is on the western bank of the Yenisei River about 2,500 km southwest of Ulakhan Sular, and shares a similar timeframe to that canid. A skull from this site described as dog-like has been lost in the past, but there exists a written description of it possessing a wide snout and a clear stop, with a skull length of 23 cm that falls outside of those of wolves.[29] |

| 16,700 | Kniegortte, Germany | Partial maxillary fragment with teeth dated 16,700–13,800 YBP.[36] Taxonomy uncertain.[13] |

| 16,300 | Monruz, Switzerland | Deciduous teeth possibly from a dog.[37] Taxonomy uncertain.[13] |

| 15,770 | Oelknitz, Germany | Phalanges, metapodia and part of distal humerus and tibia dated 15,770–13,957 YBP.[36] Taxonomy uncertain.[13] |

| 15,770 | Teufelsbrucke, Germany | Proximal metapodial fragment and first phalanx dated 15,770–13,957.[36] Taxonomy uncertain.[13] |

| 15,500–13,500 | Montespan, France | 1 atlas, 1 femur, 1 baculum dated 15,500–13,500.[38] Domestic dog.[13] |

| 15,200 | Champré-veyres-Hauterive, Switzerland | Metatarsal and two teeth, second phalanx dated 15,200–13,900 YBP.[39] Taxonomy uncertain.[13] |

| 14,999 | Le Closeau, France | 7 fragments including mandible, meta carpal, metapodial and phalanxes 14,999–14,055 YBP.[38] Domestic dog.[13] |

| 14,900 | Verholenskaya Gora, Irkutsk, Siberia | Lower jaw of a large canid. Found on the Angara river near Irkutsk about 2400 km southwest of Ulakhan Sular. Proposed as a Paleolithic dog.[29] |

| 14,600–14,100 | Kesslerloch Cave, Switzerland | Large maxillary fragment that is too small to be from a wolf. Proposed as a Paleolithic dog.[40] Taxonomy uncertain.[13] |

| 14,500 | Erralla cave, Gipuzkoa, Spain | Humerus of a dog, the dimensions of which are close to that of the dog humerus found at Pont d'Ambon.[41] Domestic dog.[13] |

| 14,223 | Bonn-Oberkassel, Germany | The "Bonn-Oberkassel dog". Undisputed dog skeleton buried with a man and woman. All three skeletal remains were found sprayed with red hematite powder.[42] The consensus is that a dog was buried along with two humans.[43] Analysis of mDNA indicates that this dog was a direct ancestor of modern dogs.[44] Domestic dog.[13] |

| 13,500 approx | Mezine, Chernigov region, Ukraine | Ancient dog-like skull proposed as being a Paleolithic dog.[6] Additionally, ancient wolf specimens found at the site. Dated to the Epigravettian period (17,000–10,000 BP). The Mezine skull is very similar in shape to the Goyet skull (36,000 YBP), Eliseevichi-1 dog skulls (16,900 YBP) and Mezhirich dog skull (13,500 YBP). The Epigravettian Mezine site is well known for its round mammoth bone dwelling.[6] Taxonomy uncertain.[13] |

| 13,500 approx | Mezhirich, Ukraine | Ancient dog-like skull proposed as being a Paleolithic dog.[6] Dated to the Epigravettian period (17,000–10,000 YBP). The Mezhirich skull is very similar in shape to the Goyet skull (36,000 YBP), the Eliseevichi-1 dog skulls (15,000 YBP) and Mezine dog skull (13,500 YBP). The Epigravettian Mezhirich site had four mammoth bone dwellings present.[6] Taxonomy uncertain.[13] |

| 13,000 | Palegawra, Iraq | Mandible[10] |

| 12,800 | Ushki I, Kamchatka, eastern Siberia | Complete skeleton buried in a buried dwelling.[45] Located 1,800 km to the southeast from Ulakhan Sular. Domestic dog.[29] |

| 12,790 | Nanzhuangtou, China | 31 fragments including a complete mandible[46] |

| 12,500 | Kartstein cave, Mechernich, Germany | Ancient dog skull. In 2013, the DNA sequence was identified as a dog.[22] |

| 12,500 | Le Morin rockshelter, Gironde, France | Skeletal remains of dogs.[47] Domestic dog.[13] |

| 12,450 | Yakutia, Siberia | Mummified carcass. The "Black Dog of Tumat" was found frozen into the ice core of an oxbow lake steep ravine at the middle course of the Syalaah River in the Ust-Yana region. DNA analysis confirmed it as an early dog.[48] |

| 12,300 | Ust'-Khaita site, Baikal region, Central Asia | Sub-adult skull located 2,400 km southwest of Ulakhan Sular and proposed as a Paleolithic dog.[29] |

| 12,000 | Ain Mallaha (Eynan) and HaYonim terrace, Israel | Three canid finds. A diminutive carnassial and a mandible, and a wolf or dog puppy skeleton buried with a human during the Natufian culture.[49] These Natufian dogs did not exhibit tooth-crowding.[50] The Natufian culture occupied the Levant, and had earlier interred a fox together with a human in the Uyun al-Hammam burial site, Jordan dated 17,700–14,750 YBP.[51] |

| 12,000 | Grotte du Moulin cave in Troubat, France | Two dogs were buried together in the by the Azilian culture.[52] |

| 10,700 | Pont d'Ambon, Dordogne, France | A number of skeletal remains of dogs.[38] In 2013, the DNA sequence was identified as a dog.[22] Domestic dog.[13] |

| 10,150 | Lawyer's Cave, Alaska, USA | Bone of a dog, oldest find in North America. DNA indicates a split from Siberian relatives 16,500 YBP, indicating that dogs may have been in Beringia earlier. Lawyer's Cave is on the Alaskan mainland east of Wrangell Island in the Alexander Archipelago of southeast Alaska.[53] |

| 9,900 | Koster Site, Illinois, USA | Three dog burials, with another single burial located 35 km away at the Stilwell II site in Pike County.[54] |

| 9,000 | Jiahu site, China | Eleven dog interments. Jaihu is a Neolithic site 22 kilometers north of Wuyang in Henan Province.[55] |

| 8,000 | Svaerdborg site, Denmark | Three different sized dog types recorded at this Maglemosian culture site.[56] |

| 7,425 | Baikal region, Central Asia (Russia) | Dog buried in a human burial ground. Additionally, a human skull was found buried between the legs of a "tundra wolf" dated 8,320 BP (but it does not match any known wolf DNA). The evidence indicates that as soon as formal cemeteries developed in Baikal, some canids began to receive mortuary treatments that closely paralleled those of humans. One dog was found buried with four red deer canine pendants around its neck dated 5,770 BP. Many burials of dogs continued in this region with the latest finding at 3,760 BP, and they were buried lying on their right side and facing towards the east as did their humans. Some were buried with artifacts, e.g., stone blades, birch bark and antler bone.[57] |

| 7,000 | Tianluoshan archaeological site, Zhejiang province, China | In 2020, an mDNA study of ancient dog fossils from the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins of southern China showed that most of the ancient dogs fell within haplogroup A1b, as do the Australian dingoes and the pre-colonial dogs of the Pacific, but in low frequency in China today. The specimen from the Tianluoshan archaeological site is basal to the entire lineage. The dogs belonging to this haplogroup were once widely distributed in southern China, then dispersed through Southeast Asia into New Guinea and Oceania, but were replaced in China 2,000 YBP by dogs of other lineages.[58] |

Early domestication debate

[edit]Among archeologists, the proposed timing of the development of a relationship between humans and wolves is debated. There exists two schools of thought.[18] The early domestication theory argues that the relationship commenced once humans moved into the colder parts of Eurasia around 35,000 YBP, which is when the proposed Paleolithic dogs first began to appear.[6][27][59] Wolves that were adjusting to live with humans may have developed shorter, wider skulls and more steeply-rising foreheads that would make wolf facial expressions easier to interpret.[18] The late domestication theory argues that Paleolithic dogs are an unusual phenotype of wolf and that dogs appeared only when they could be phenotypically distinguishable from the wolf, which is usually based on a reduction in size.[60][61][62][34][63] This argument maintains that domesticated dogs are more clearly identified when they are associated with human occupation, and those interred side by side with human remains provide the most conclusive evidence,[61] commencing with the 14,200 years old Bonn-Oberkassel dog.

The debate centres around Homo sapiens and if they had entered into cooperation with wolves soon after they moved into Eurasia, and if so when and where did these wolves change into domesticated dogs. In arguing that domestication leads to reduction in size, the late domestication theory ignores that modern horses and pigs are larger than their wild ancestors. It also ignores that if hunter-gathers entered into a hunting relationship with wolves then there would be no need of selection for a reduction in size. A reduction in size would have occurred much later when humans moved into agricultural villages. The late domestication theory does not consider the possibility that humans may have formed a relationship with non-domesticated wolves and that dogs in the early stages of domestication might be indistinguishable from wolves. According to indigenous North Americans, over the past 20,000 years the canids living with them were wolves that could not be distinguished as dogs.[18]

The problem in attempting to identify when and where domestication occurred is the possibility that the process of domestication occurred in a number of places and at a number of times throughout prehistory.[18] Early dog remains have been found in different parts of the world. This suggests that dog domestication may have taken place in different regions independently by hunter-gatherers, in some cases at the same time[64] and in other cases at different times,[65] with different wolf subspecies producing different dog lineages.[66][65] Therefore, the number of dog domestication events is not known.[67] A study of the maternal mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) shows that dogs fall within 4 mDNA clades,[22] indicating that dogs are derived from 4 separate lineages and therefore there may not have been a single domestication event.[18]

A domestication study looked at the reasons why the archeological record that is based on the dating of fossil remains often differed from the genetic record contained within the cells of living species. The study concluded that our inability to date domestication is because domestication is a continuum and there is no single point where we can say that a species was clearly domesticated using these two techniques. The study proposes that changes in morphology across time and how humans were interacting with the species in the past needs to be considered in addition to these two techniques.[68]

..."wild" and "domesticated" exist as concepts along a continuum, and the boundary between them is often blurred — and, at least in the case of wolves, it was never clear to begin with.

— Raymond Pierotti[69]

Relationship to the domestic dog

[edit]In 2013, a major Mitochondrial DNA study has found that divergence times from wolf to dog implies a European origin of the domestic dog dating 18,800-32,100 years ago, which supports the hypothesis that dog domestication preceded the emergence of agriculture and occurred in the context of European hunter-gatherer cultures.[22]

In 2009, a study proposed that there was a low frequency of recognized dog skulls in Upper Paleolithic sites because existing specimens had not yet been recognized as dogs. The study looked at the 2 Eliseevichi-1 dog skulls in comparison to much earlier Late Pleistocene but morphologically similar fossil skulls that had been found across Europe, and proposed the much earlier specimens were Paleolithic dogs that were morphologically and genetically distinct from the Pleistocene wolves living in Europe at that time. The study looked at 117 skulls of recent and fossil large canids. Several skulls of fossil large canids from sites in Belgium, Ukraine and Russia were examined using multivariate analysis to look for evidence of the presence of Paleolithic dogs that were separate from Pleistocene wolves. Reference groups included the Eliseevichi-1 prehistoric dogs, recent dogs and wolves.

The osteometric analysis of the skulls indicated that the Paleolithic dogs fell outside the skull ranges of the Pleistocene wolf group and the modern wolf group, and were closer related to those of the Eliseevichi-1 prehistoric dog group. The fossil large canid from Goyet, Belgium dated at 36,000 YBP was clearly different from the recent wolves, resembling most closely the Eliseevichi-1 prehistoric dogs and suggesting that dog domestication had already started during the Aurignacian. The two Epigravettian Mezine, Ukraine and Mezhirich, Ukraine skulls were also identified as being Paleolithic dogs. Collagen analysis indicated that the Paleolithic dogs associated with human hunter-gatherer camp-sites (Eliseevichi-1, Mezine and Mezhirich) had been specifically eating reindeer, while other predator species in those locations and times had eaten a range of prey.[6][21]

Further studies later looked at wolf-like fossils from Paleolithic hunter-gatherer sites across Europe and proposed to have identified Paleolithic dogs at Predmosti (Czech Republic 26,000-27,000 YBP), Kostenki-8 (Russia 23,000-27,700 YBP), Kostenki-1 (Russia 22,000-24,000 BP), Kostenki-17 (Russia Upper Paleolithic) and Verholenskaya (Russia late glacial).[26] In the human burial zone at the Predmosti site, 3 Paleolithic skulls were found that resemble those of a Siberian husky but they were larger and heavier than the modern husky. For one skull, "a large bone fragment is present between the upper and lower incisors that extends several centimetres into the mouth cavity. The size, thickness and shape of the fragment suggest that it could be a fragment of a bone of a large mammal, probably from a mammoth. The position of the bone fragment in the mouth and the articulated state of the lower jaw with the skull indicate that this mammoth bone fragment was inserted artificially into the mouth of the dog post-mortem." The morphology of some wolf-like fossils was such that they could not be assigned to either the Pleistocene wolf nor Paleolithic dog groups.[27]

It has been proposed that based on the genetic evidence of modern dogs being traced to the ancient wolves of Europe, the archaeological evidence of the Paleolithic dog remains being found at known European hunting camp-sites, their morphology, and collagen analysis that indicated that their diet had been artificially restricted compared to nearby wolves, that the Paleolithic dog was domesticated. It has also been hypothesized that the Paleolithic dog may have provided the stock from which early dogs arose, or alternatively that they are a type of wolf that is not known to science.[6][21] In 2016, a study discounted the use of the Paleolithic dogs from the Predmosti site as pack animals.[70]

There has been ongoing debate in the scientific press about what the fossil remains of the Paleolithic dog might be, with some commenters declaring them as either wolves or a unique form of wolf. These include a first article proposing the Paleolithic dog,[6] its refutation,[60] a counter to the refutation,[71] a second article,[27] its refutation,[61] a third article that includes a counter to the refutation,[26] its refutation,[62] a counter to the refutation,[72] another refutation,[34][63] support given based on bone collagen analysis,[1] and the identification of an ancient paleolithic dog in Yakutia.[29]

As the ancestor of the dog has not been identified by scientists, this debate continues.

Two domestication events

[edit]Studies have suggested that it was possible for multiple primitive forms of the dog to have existed, including in Europe.[73] European dog populations had undergone extensive turnover during the last 15,000 years that has erased the genomic signature of early European dogs,[74][75] the genetic heritage of the modern breeds has become blurred due to admixture,[56] and there was the possibility of past domestication events that had died out or had been largely replaced by more modern dog populations.[74]

In 2016, a study proposed that dogs may have been domesticated separately in both Eastern and Western Eurasia from two genetically distinct and now extinct wolf populations. East Eurasian dogs then made their way with migrating people to Western Europe between 14,000 and 6,400 YBP where they partially replaced the dogs of Europe.[76] Two domestication events in Western Eurasia and Eastern Eurasia have recently been found for the domestic pig.[76][77]

As the taxonomic classification of the "proto-dog" Paleolithic dogs as being either dogs or wolves remains controversial, they were excluded from the study.[76]

Goyet dog

[edit]- Genus Canis, species indeterminate

In 2009, a study looked at 117 skulls of recent and fossil large canids. None of the 10 canid skulls from the Belgian caves of Goyet, Trou du Frontel, Trou de Nutons, and Trou de Chaleux could be classified, so the team took as their basic assumption that all of these canid samples were wolves.[21] The DNA sequence of seven of the skulls indicated seven unique haplotypes that represented ancient wolf lineages lost until now. The osteometric analysis of the skulls showed that one large canid fossil from Goyet was clearly different from recent wolves, resembling most closely the Eliseevichi-1 dogs (15,000 YBP) and so was identified as a Paleolithic dog.[6][78] The analysis indicated that the Belgian fossil large canids in general preyed on horse and large bovids.[6][27]

In November 2013, a DNA study sequenced three haplotypes from the ancient Belgium canids (the Goyet dog – Belgium 36,000 YBP cataloged as Canis species Genbank accession number KF661079, and with Belgium 30,000 YBP KF661080 and 26,000 years YBP KF661078 cataloged as Canis lupus) and found they formed the most diverging group. Although the cranial morphology of the Goyet dog has been interpreted as dog-like, its mitochondrial DNA relation to other canids places it as an ancient sister-group to all modern dogs and wolves rather than a direct ancestor. However, in 2015 three-dimensional geometric morphometric analyses indicated this, and the Eliseevichi-1 dog, is more likely from a wolf.[34][33] Belgium 26,000 YBP has been found to be uniquely large but was found not to be related to the Beringian wolf. This Belgium canid clade may represent a phenotypically distinct and not previously recognized population of grey wolf, or the Goyet dog may represent an aborted domestication episode. If so, there may have been originally more than one ancient domestication event for dogs[22] as there was for domestic pigs.[77] A 2016 review proposed that it most likely represents an extinct morphologically and genetically divergent wolf population.[33]

Altai dog

[edit]- Genus Canis, species indeterminate

In 2011, a study looked at the well-preserved 33,000-year-old skull and left mandible of a dog-like canid that was excavated from Razboinichya Cave in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia (Central Asia). The morphology was compared to the skulls and mandibles of large Pleistocene wolves from Predmosti, Czech Republic, dated 31,000 YBP, modern wolves from Europe and North America, and prehistoric Greenland dogs from the Thule period (1,000 YBP or later) to represent large-sized but unimproved fully domestic dogs. "The Razboinichya Cave cranium is virtually identical in size and shape to prehistoric Greenland dogs" and not the ancient nor modern wolves. However, the lower carnassial tooth fell within the lower range of values for prehistoric wolves and was only slightly smaller than modern European wolves, and the upper carnassial tooth fell within the range of modern wolves. "We conclude, therefore, that this specimen may represent a dog in the very early stages of domestication, i.e. an incipient dog, rather than an aberrant wolf... The Razboinichya Cave specimen appears to be an incipient dog...and probably represents wolf domestication disrupted by the climatic and cultural changes associated with the Last Glacial Maximum".[79]

In 2007, a mtDNA analysis of extinct eastern Beringian wolves showed that two ancient wolves from Ukraine dated 30,000 YBP and 28,000 YBP and the 33,000 YBP Altai dog had the same sequence as six Beringian wolves,[80] indicating a common maternal ancestor. In 2013, a DNA study of the Altai dog deposited the sequence in GenBank with a classification of Canis lupus familiaris (dog). "The analyses revealed that the unique haplotype of the Altai dog is more closely related to modern dogs and prehistoric New World canids than it is to contemporary wolves... This preliminary analysis affirms the conclusion that the Altai specimen is likely an ancient dog with shallow divergence from ancient wolves. These results suggest a more ancient history of the dog outside of the Middle East or East Asia." The haplotype groups closest to the Altai dog included such diverse breeds as the Tibetan mastiff, Newfoundland, Chinese crested, cocker spaniel and Siberian husky.[24]

In November 2013, a study looked at 18 fossil canids and compared these with the complete mitochondrial genome sequences from 49 modern wolves and 77 modern dogs. A more comprehensive analysis of the complete mDNA found that the phylogenetic position of the Altai dog as being either dog or wolf was inconclusive and cataloged its sequence as Canis species GenBank accession number JX173682. Of four tests, 2 tests showed its sequence to fall within the wolf clade and 2 tests within the dog clade. The sequence strongly suggests a position at the root of a clade uniting two ancient wolf genomes, two modern wolves, as well as two dogs of Scandinavian origin. However, the study does not support its recent common ancestry with the great majority of modern dogs. The study suggests that it may represent an aborted domestication episode. If so, there may have been originally more than one ancient domestication event for dogs[22] as there was for domestic pigs.[77]

In 2017, two prominent evolutionary biologists reviewed all of the evidence available on dog divergence and supported the specimens from the Altai mountains as being those of dogs from a lineage that is now extinct and that was derived from a population of small wolves that is also now extinct.[25]

Local unknown wolves

[edit]Ecological factors including habitat type, climate, prey specialization and predatory competition will greatly influence wolf genetic population structure and cranio-dental plasticity.[81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89] Therefore, within the Pleistocene grey wolf population the variations between local environments would have encouraged a range of wolf ecotypes that were genetically, morphologically and ecologically distinct from one another.[89]

There are a small number of Canis remains that have been found at Goyet Cave, Belgium (36,500 YBP)[6] Razboinichya Cave, Russia (33,500 YBP)[79] Kostenki 8, Russia (33,500-26,500 YBP)[72] Predmosti, Czech Republic (31,000 YBP)[27] and Eliseevichi-1, Russia (17,000 YBP).[5] Based on cranial morphometric study of the characteristics thought to be associated with the domestication process, these have been proposed as early Paleolithic dogs.[72] These characteristics of shortened rostrum, tooth crowding, and absence or rotation of premolars have been documented in both ancient and modern wolves.[60][87][89][80][90][91] Rather than representing early dogs, these specimens may represent an extinct morphologically and genetically divergent wolf population.[33][56][89]

However, regardless of it eventually proving to be either a proto-dog or an unknown species of wolf, the original proposal was that the "Paleolithic dog" was domesticated.[6]

In 2021, a study found that the cranial measurements of a number of Paleolithic dog specimens exhibited a relatively shorter skull and a relatively wider palate and brain case when compared with Pleistocene and recent northern wolves, and that these features are the morphological signs of domestication.[92]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Bocherens, H (2015). "Reconstruction of the Gravettian food-web at Předmostí I using multi-isotopic tracking (13C, 15N, 34S) of bone collagen". Quaternary International. 359–360: 211–228. Bibcode:2015QuInt.359..211B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.09.044.

- ^ Pidoplichko, I. G. (1969) Late Palaeolithic dwellings of Mammoth bones in the Ukraine. Academy of Sciences of the Ukraine. Institute of Zoology. Nauka, Doumka, Kiev. (in Russian)

- ^ a b Olsen, S.J. (2000). "8". In Kipple, K.F.; Ornelas, K.C. (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge University Press. p. 513. ISBN 978-0-521-40214-9.

- ^ Pidoplichko I.G. (1998) Upper Paleolithic Dwellings of Mammoth Bones in the Ukraine. Oxford: BAR International Series 712

- ^ a b c Sablin, Mikhail V.; Khlopachev, Gennady A. (2002). "The Earliest Ice Age Dogs:Evidence from Eliseevichi I" (PDF). Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Germonpré, Mietje; Sablin, Mikhail V.; Stevens, Rhiannon E.; Hedges, Robert E.M.; Hofreiter, Michael; Stiller, Mathias; Despre's, Viviane R. (2009). "Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes". Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (2): 473–490. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.09.033.

- ^ a b c Zeder MA (2012). "The domestication of animals". Journal of Anthropological Research. 68 (2): 161–190. doi:10.3998/jar.0521004.0068.201. S2CID 85348232.

- ^ a b Lyudmila N. Trut (1999). "Early Canid Domestication: The Farm-Fox Experiment" (PDF). American Scientist. 87 (March–April): 160–169. Bibcode:1999AmSci..87.....T. doi:10.1511/1999.2.160. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Morey Darcy F (1992). "Size, shape, and development in the evolution of the domestic dog". Journal of Archaeological Science. 19 (2): 181–204. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(92)90049-9.

- ^ a b Turnbull Priscilla F.; Reed Charles A. (1974). "The fauna from the terminal Pleistocene of Palegawra Cave". Fieldiana: Anthropology. 63: 81–146.

- ^ a b Bocherens, Hervé (2015). "Isotopic tracking of large carnivore palaeoecology in the mammoth steppe". Quaternary Science Reviews. 117: 42–71. Bibcode:2015QSRv..117...42B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.03.018.

- ^ a b Prassack, Kari A.; Dubois, Josephine; Lázničková-Galetová, Martina; Germonpré, Mietje; Ungar, Peter S. (2020). "Dental microwear as a behavioral proxy for distinguishing between canids at the Upper Paleolithic (Gravettian) site of Předmostí, Czech Republic". Journal of Archaeological Science. 115 105092. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2020.105092. S2CID 213669558.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Thalmann, Olaf; Perri, Angela R. (2018). "Paleogenomic Inferences of Dog Domestication". In Lindqvist, C.; Rajora, O. (eds.). Paleogenomics. Population Genomics. Springer, Cham. pp. 273–306. doi:10.1007/13836_2018_27. ISBN 978-3-030-04752-8.

- ^ Clutton-Brock, J. (1995). "Chapter 1". In James Serpell (ed.). The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People. Cambridge University Press Press. pp. 7–20. ISBN 978-0-521-42537-7.

- ^ Pei, W. (1934). "The carnivora from locality 1 of Choukoutien". Palaeontologia Sinica, Series C, vol. 8, Fascicle 1. Geological Survey of China, Beijing. pp. 1–45.

- ^ Thurston, M. (1996). "Ch.1-Leaving the Garden". The Lost History of the Canine Race: Our 15,000-Year Love Affair With Dogs. Andrews McMeel. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8362-0548-0.

- ^ Vila, C. (1997). "Multiple and ancient origins of the domestic dog". Science. 276 (5319): 1687–9. doi:10.1126/science.276.5319.1687. PMID 9180076.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pierotti & Fogg 2017, pp. 83–93

- ^ Oetjens, Matthew T; Martin, Axel; Veeramah, Krishna R; Kidd, Jeffrey M (2018). "Analysis of the canid Y-chromosome phylogeny using short-read sequencing data reveals the presence of distinct haplogroups among Neolithic European dogs". BMC Genomics. 19 (1): 350. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-4749-z. PMC 5946424. PMID 29747566.

- ^ Camarós E, Münzel SC, Mn C, Rivals F, Conard NJ. The evolution of Paleolithic hominincarnivore interaction written in teeth: stories from the Swabian Jura (Germany). J Archaeol Sci Rep. 2016;6:798–809

- ^ a b c d Shipman, P. (2011). The Animal Connection: A New Perspective on What Makes Us Human. W W Norton & Co New York. pp. 211–218. ISBN 978-0-393-07054-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thalmann, O.; Shapiro, B.; Cui, P.; Schuenemann, V.J.; Sawyer, S.K.; Greenfield, D.L.; Germonpré, M.B.; Sablin, M.V.; López-Giráldez, F.; Domingo-Roura, X.; Napierala, H.; Uerpmann, H-P.; Loponte, D.M.; Acosta, A.A.; Giemsch, L.; Schmitz, R.W.; Worthington, B.; Buikstra, J.E.; Druzhkova, A.S.; Graphodatsky, A.S.; Ovodov, N.D.; Wahlberg, N.; Freedman, A.H.; Schweizer, R.M.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Leonard, J.A.; Meyer, M.; Krause, J.; Pääbo, S.; Green, R.E.; Wayne, Robert K. (15 November 2013). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs". Science. 342 (6160): 871–874. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..871T. doi:10.1126/science.1243650. PMID 24233726. S2CID 1526260. refer Supplementary material Page 27 Table S1

- ^ Skoglund, P. (2015). "Ancient wolf genome reveals an early divergence of domestic dog ancestors and admixture into high-latitude breeds". Current Biology. 25 (11): 1515–9. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.019. PMID 26004765.

- ^ a b Druzhkova, A. (2013). "Ancient DNA analysis affirms the canid from Altai as a primitive dog". PLOS ONE. 8 (3) e57754. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...857754D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057754. PMC 3590291. PMID 23483925.

- ^ a b Freedman, Adam H; Wayne, Robert K (2017). "Deciphering the Origin of Dogs: From Fossils to Genomes". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 5: 281–307. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110937. PMID 27912242. S2CID 26721918.

- ^ a b c d Germonpré, Mietje; Laznickova-Galetova, Martina; Losey, Robert J.; Raikkonen, Jannikke; Sablin, Mikhail V. (2014). "Large canids at the Gravettian Predmostí site, the Czech Republic:The mandible". Quaternary International. xxx: 1–19. Bibcode:2015QuInt.359..261G. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.07.012.

- ^ a b c d e f Germonpré, Mietje; Laznickova-Galetova, Martina; Sablin, Mikhail V. (2012). "Palaeolithic dog skulls at the Gravettian Predmosti site, the Czech Republic". Journal of Archaeological Science. 39: 184–202. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.09.022.

- ^ Viegas, Jennifer (October 7, 2011). "Prehistoric dog found with mammoth bone in mouth". Discovery News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Germonpré, Mietje; Fedorov, Sergey; Danilov, Petr; Galeta, Patrik; Jimenez, Elodie-Laure; Sablin, Mikhail; Losey, Robert J. (2017). "Palaeolithic and prehistoric dogs and Pleistocene wolves from Yakutia: Identification of isolated skulls". Journal of Archaeological Science. 78: 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2016.11.008.

- ^ Garcia, M. (2005). "Ichnologie générale de la grotte Chauvet". Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française. 102: 103–108. doi:10.3406/bspf.2005.13341.

- ^ Ledoux, Lysianna; Boudadi-Maligne, Myriam (2015). "The contribution of geometric morphometric analysis to prehistoric ichnology: The example of large canid tracks and their implication for the debate concerning wolf domestication". Journal of Archaeological Science. 61: 25–35. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2015.04.020.

- ^ Lisowska, Anna (25 November 2019). "Amazingly preserved puppy with whiskers, eyelashes, hair and velvety nose intact puzzle scientists". The Siberian Times. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d Machugh, David E.; Larson, Greger; Orlando, Ludovic (2016). "Taming the Past: Ancient DNA and the Study of Animal Domestication". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 5: 329–351. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022516-022747. PMID 27813680. S2CID 21991146.

- ^ a b c d Drake, Abby Grace; Coquerelle, Michael; Colombeau, Guillaume (5 February 2015). "3D morphometric analysis of fossil canid skulls contradicts the suggested domestication of dogs during the late Paleolithic". Scientific Reports. 5 (2899): 8299. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5E8299D. doi:10.1038/srep08299. PMC 5389137. PMID 25654325.

- ^ Pierotti & Fogg 2017, pp. 101

- ^ a b c Musil R (2000) Evidence for the domestication of wolves in central European Magdalenian sites. Dogs through time: an archaeological perspective, ed Crockford SJ (British Archaeological Reports, Oxford, England), pp 21-28.

- ^ Müller W. Les témoins animaux. In: Bullinger J, Leesch D, Plumettaz N (eds) Le site magdalénien de Monruz: Premiers éléments pour l'analyse d'un habitat de plein air. Service et musée cantonal d'archéologie de Neuchâtel; 2006. p. 123–37. ["Animal witnesses". English-translated details can be found in: "Street, M., Napierala, H. & Janssens, L. 2015: The dog from Bonn-Oberkassel. Paper presented at the Symposium "A Century of Research on the Late Glacial Burial of Bonn-Oberkassel. New Research on the Federmesser-Gruppen/Azilian", October 23rd–25th, 2015, Bonn, Germany."]

- ^ a b c Pionnier-Capitan, M; et al. (2011). "New evidence for Upper Palaeolithic small domestic dogs in South-Western Europe". J. Archaeol. Sci. 38 (9): 2123–2140. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.02.028.

- ^ Morel P & Müller W (2000) Un campement magdalénien au bord du lac de Neuchâtel, étude archéozoologique (secteur 1) (Musée cantonal d'archéologie, Neuchâtel)

- ^ Napierala H, Uerpmann H-P. A 'new' palaeolithic dog from central Europe. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2012;22(2):127–37.

- ^ Vigne J-D. L'humérus de chien magdalénien de Erralla (Gipuzkoa, Espagne) et la domestication tardiglaciaire du loup en Europe. Munibe. 2005;51:279–87. ["The Magdalenian dog humerus of Erralla (Gipuzkoa, Spain) and the lateglacial domestication of the wolf in Europe." English description found in "Street, M., Napierala, H. & Janssens, L. 2015: The dog from Bonn-Oberkassel. Paper presented at the Symposium "A Century of Research on the Late Glacial Burial of Bonn-Oberkassel. New Research on the Federmesser-Gruppen/Azilian", October 23rd–25th, 2015, Bonn, Germany."]

- ^ Janssens, Luc; Giemsch, Liane; Schmitz, Ralf; Street, Martin; Van Dongen, Stefan; Crombé, Philippe (2018). "A new look at an old dog: Bonn-Oberkassel reconsidered". Journal of Archaeological Science. 92: 126–138. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.01.004. hdl:1854/LU-8550758.

- ^ Street, Martin & Janssens, Luc & Napierala, Hannes. (2015). Street, M., Napierala, H. & Janssens, L. 2015: The late Palaeolithic dog from Bonn-Oberkassel in context. In: The Late Glacial Burial from Oberkassel Revisited (L. Giemsch / R. W. Schmitz eds.), Rheinische Ausgrabungen 72, 253-274. ISBN 978-3-8053-4970-3. Rheinische Ausgrabungen.

- ^ Liane Giemsch, Susanne C. Feine, Kurt W. Alt, Qiaomei Fu, Corina Knipper, Johannes Krause, Sarah Lacy, Olaf Nehlich, Constanze Niess, Svante Pääbo, Alfred Pawlik, Michael P. Richards, Verena Schünemann, Martin Street, Olaf Thalmann, Johann Tinnes, Erik Trinkaus & Ralf W. Schmitz. "Interdisciplinary investigations of the late glacial double burial from Bonn-Oberkassel". Hugo Obermaier Society for Quaternary Research and Archaeology of the Stone Age: 57th Annual Meeting in Heidenheim, 7th – 11th April 2015, 36-37

- ^ Dikov NN (1996) The Ushki sites, Kamchatka Peninsula. American Beginnings: the Prehistory and Palaeoecology of Beringia, ed West FH (University of Chicago Press, Chicago), pp 244-250.

- ^ Jing Y (2010) Zhongguo gu dai jia yang dong wu de dong wu kao gu xue yan jiu (The zooarchaeology of domesticated animals in ancient China). Quaternary Sciences 30(2):298–306.

- ^ Boudadi-Maligne M, Mallye J-B, Langlais M, Barshay-Szmidt C. Magdalenian dog remains from Le Morin rock-shelter (Gironde, France). Socio-economic implications of a zootechnical innovation. PALEO Revue d'archéologie préhistorique. 2012;(23):39–54.

- ^ Leisowska, A (2015). "Autopsy carried out in Far East on world's oldest dog mummified by ice". Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ Davis, F. (1978). "Evidence for domestication of the dog 12,000 years ago in the Natufian of Palestine". Nature. 276 (5688): 608–610. Bibcode:1978Natur.276..608D. doi:10.1038/276608a0. S2CID 4356468.

- ^ Tchernov, Eitan; Valla, François F (1997). "Two New Dogs, and Other Natufian Dogs, from the Southern Levant". Journal of Archaeological Science. 24: 65–95. doi:10.1006/jasc.1995.0096.

- ^ Maher, Lisa A; Stock, Jay; Finney, Sarah; Heywood, James J. N; Miracle, Preston T; Banning, Edward B (2011). "A Unique Human-Fox Burial from a Pre-Natufian Cemetery in the Levant (Jordan)". PLOS ONE. 6 (1) e15815. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...615815M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015815. PMC 3027631. PMID 21298094.

- ^ Boudadi‐Maligne, Myriam; Mallye, Jean‐Baptiste; Ferrié, Jean‐Georges; Costamagno, Sandrine; Barshay‐Szmidt, Carolyn; Deguilloux, Marie‐France; Pémonge, Marie‐Hélène; Barbaza, Michel (2020). "The earliest double dog deposit in the Palaeolithic record: The case of the Azilian level of Grotte‐abri du Moulin (Troubat, France)" (PDF). International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 30 (3): 382–394. doi:10.1002/oa.2857. S2CID 213423831.

- ^ Da Silva Coelho, Flavio Augusto; Gill, Stephanie; Tomlin, Crystal M.; Heaton, Timothy H.; Lindqvist, Charlotte (2021). "An early dog from southeast Alaska supports a coastal route for the first dog migration into the Americas". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 288 (1945). doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.3103. PMC 7934960. PMID 33622130. S2CID 232020982.

- ^ Perri, Angela; Widga, Chris; Lawler, Dennis; Martin, Terrance; Loebel, Thomas; Farnsworth, Kenneth; Kohn, Luci; Buenger, Brent (2019). "New Evidence of the Earliest Domestic Dogs in the Americas". American Antiquity. 84: 68–87. doi:10.1017/aaq.2018.74.

- ^ Susan J. Crockford, A Practical Guide to In Situ Dog Remains for the Field Archaeologist, 2009

- ^ a b c Larson G (2012). "Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography". PNAS. 109 (23): 8878–8883. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.8878L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203005109. PMC 3384140. PMID 22615366.

- ^ Losey, R. (2011). "Canids as persons: Early Neolithic dog and wolf burials, Cis-Baikal, Siberia". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 30 (2): 174–189. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2011.01.001. hdl:10261/58553.

- ^ Zhang, Ming; Sun, Guoping; Ren, Lele; Yuan, Haibing; Dong, Guanghui; Zhang, Lizhao; Liu, Feng; Cao, Peng; Ko, Albert Min-Shan; Yang, Melinda A.; Hu, Songmei; Wang, Guo-Dong; Fu, Qiaomei (2020). "Ancient DNA evidence from China reveals the expansion of Pacific dogs". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 37 (5): 1462–1469. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz311. PMC 7182212. PMID 31913480.

- ^ Shipman 2015, pp. 167–193

- ^ a b c Crockford SJ, Kuzmin YV (2012) Comments on Germonpre et al., Journal of Archaeological Science 36, 2009 "Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes"

- ^ a b c Boudadi-Maligne, M. (2014). "A biometric re-evaluation of recent claims for Early Upper Palaeolithic wolf domestication in Eurasia". Journal of Archaeological Science. 45: 80–89. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.02.006.

- ^ a b Morey, Darcy F. (2014). "In search of Paleolithic dogs: A quest with mixed results". Journal of Archaeological Science. 52: 300–307. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.08.015.

- ^ a b Morey, Darcy F; Jeger, Rujana (2015). "Paleolithic dogs: Why sustained domestication then?". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 3: 420–428. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.06.031.

- ^ Derr 2011, pp. 51

- ^ a b Spotte, S. (2012). "Ch.2-What makes a dog?". Societies of Wolves and Free-ranging Dogs. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-107-01519-7.

- ^ Morey, D. (1994). "The Early Evolution of the Domestic Dog". American Scientist. 82 (4). Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society: 336–347. Bibcode:1994AmSci..82..336M. JSTOR 29775234.

- ^ Morey, D. (2010). "Ch.3". Dogs: Domestication and the Development of a Social Bond. Cambridge University Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-521-75743-0.

- ^ Irving-Pease, Evan K; Frantz, Laurent A.F; Sykes, Naomi; Callou, Cécile; Larson, Greger (2018). "Rabbits and the Specious Origins of Domestication". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 33 (3): 149–152. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2017.12.009. PMID 29454669. S2CID 3380288.

- ^ Pierotti & Fogg 2017, pp. 5–6

- ^ Germonpré, Mietje; Losey, Robert; Lázničková-Galetová, Martina; Galeta, Patrik; Sablin, Mikhail V.; Latham, Katherine; Räikkönen, Jannikke (2016). "Spondylosis deformans in three large canids from the Gravettian Předmostí site: Comparison with other canid populations". International Journal of Paleopathology. 15: 83–91. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2016.08.007. PMID 29539558.

- ^ Germonpré, Mietje; Sablin, MV; Despres, V; Hofreiter, M; Laznickova-Galetova, M; et al. (2013). "Palaeolithic dogs and the early domestication of the wolf: a reply to the comments of Crockford and Kuzmin (2012)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40: 786–792. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.06.016.

- ^ a b c Germonpré, Mietje; Sablin, Mikhail V.; Laznickova-Galetova, Martina; Despre's, Viviane R.; Stevens, Rhiannon E.; Stiller, Mathias; Hofreiter, Michael (2015). "Palaeolithic dogs and Pleistocene wolves revisited: a reply to Morey (2014)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 54: 210–216. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.11.035.

- ^ Wang, G (2015). "Out of southern East Asia: the natural history of domestic dogs across the world". Cell Research. 26 (1): 21–33. doi:10.1038/cr.2015.147. PMC 4816135. PMID 26667385.

- ^ a b Shannon, L (2015). "Genetic structure in village dogs reveals a Central Asian domestication origin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (44): 13639–13644. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11213639S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1516215112. PMC 4640804. PMID 26483491.

- ^ Malmström, Helena; Vilà, Carles; Gilbert, M; Storå, Jan; Willerslev, Eske; Holmlund, Gunilla; Götherström, Anders (2008). "Barking up the wrong tree: Modern northern European dogs fail to explain their origin". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 8: 71. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-71. PMC 2288593. PMID 18307773.

- ^ a b c Frantz, L. A. F.; Mullin, V. E.; Pionnier-Capitan, M.; Lebrasseur, O.; Ollivier, M.; Perri, A.; Linderholm, A.; Mattiangeli, V.; Teasdale, M. D.; Dimopoulos, E. A.; Tresset, A.; Duffraisse, M.; McCormick, F.; Bartosiewicz, L.; Gal, E.; Nyerges, E. A.; Sablin, M. V.; Brehard, S.; Mashkour, M.; b l Escu, A.; Gillet, B.; Hughes, S.; Chassaing, O.; Hitte, C.; Vigne, J.-D.; Dobney, K.; Hanni, C.; Bradley, D. G.; Larson, G. (2016). "Genomic and archaeological evidence suggest a dual origin of domestic dogs". Science. 352 (6290): 1228–31. Bibcode:2016Sci...352.1228F. doi:10.1126/science.aaf3161. PMID 27257259. S2CID 206647686.

- ^ a b c Frantz, L. (2015). "Evidence of long-term gene flow and selection during domestication from analyses of Eurasian wild and domestic pig genomes". Nature Genetics. 47 (10): 1141–1148. doi:10.1038/ng.3394. PMID 26323058. S2CID 205350534.

- ^ Royal Belgium Institute of Natural Sciences. "Goyet skull photo".

- ^ a b Ovodov, N. (2011). "A 33,000-year-old incipient dog from the Altai Mountains of Siberia: Evidence of the earliest domestication disrupted by the Last Glacial Maximum". PLOS ONE. 6 (7) e22821. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622821O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022821. PMC 3145761. PMID 21829526.

- ^ a b Leonard, J. (2007). "Megafaunal extinctions and the disappearance of a specialized wolf ecomorph". Current Biology. 17 (13): 1146–50. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.072. hdl:10261/61282. PMID 17583509. S2CID 14039133.

- ^ Carmichael, L. E.; Nagy, J. A.; Larter, N. C.; Strobeck, C. (2001). "Prey specialization may influence patterns of gene flow in wolves of the Canadian Northwest". Molecular Ecology. 10 (12): 2787–98. doi:10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01408.x. PMID 11903892. S2CID 29313917.

- ^ Carmichael, L.E., 2006. Ecological Genetics of Northern Wolves and Arctic Foxes. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Alberta.

- ^ Geffen, ELI; Anderson, Marti J.; Wayne, Robert K. (2004). "Climate and habitat barriers to dispersal in the highly mobile grey wolf". Molecular Ecology. 13 (8): 2481–90. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02244.x. PMID 15245420. S2CID 4840903.

- ^ Pilot, Malgorzata; Jedrzejewski, Wlodzimierz; Branicki, Wojciech; Sidorovich, Vadim E.; Jedrzejewska, Bogumila; Stachura, Krystyna; Funk, Stephan M. (2006). "Ecological factors influence population genetic structure of European grey wolves". Molecular Ecology. 15 (14): 4533–53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03110.x. PMID 17107481. S2CID 11864260.

- ^ Musiani, Marco; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Cluff, H. Dean; Gates, C. Cormack; Mariani, Stefano; Paquet, Paul C.; Vilà, Carles; Wayne, Robert K. (2007). "Differentiation of tundra/taiga and boreal coniferous forest wolves: Genetics, coat colour and association with migratory caribou". Molecular Ecology. 16 (19): 4149–70. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03458.x. PMID 17725575. S2CID 14459019.

- ^ Hofreiter, Michael; Barnes, Ian (2010). "Diversity lost: Are all Holarctic large mammal species just relict populations?". BMC Biology. 8: 46. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-46. PMC 2858106. PMID 20409351.

- ^ a b Flower, Lucy O.H.; Schreve, Danielle C. (2014). "An investigation of palaeodietary variability in European Pleistocene canids". Quaternary Science Reviews. 96: 188–203. Bibcode:2014QSRv...96..188F. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.04.015.

- ^ Leonard, Jennifer (2014). "Ecology drives evolution in grey wolves" (PDF). Evolution Ecology Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-15. Retrieved 2016-04-05.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d Perri, Angela (2016). "A wolf in dog's clothing: Initial dog domestication and Pleistocene wolf variation". Journal of Archaeological Science. 68: 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2016.02.003.

- ^ Boudadi-Maligne, M., 2010. Les Canis pleistocenes du sud de la France: approche biosystematique, evolutive et biochronologique. Ph.D. dissertation. Université de Bordeaux 1

- ^ Dimitrijević, V.; Vuković, S. (2015). "Was the Dog Locally Domesticated in the Danube Gorges? Morphometric Study of Dog Cranial Remains from Four Mesolithic-Early Neolithic Archaeological Sites by Comparison with Contemporary Wolves". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 25: 1–30. doi:10.1002/oa.2260.

- ^ Galeta, Patrik; Lázničková‐Galetová, Martina; Sablin, Mikhail; Germonpré, Mietje (2021). "Morphological evidence for early dog domestication in the European Pleistocene: New evidence from a randomization approach to group differences". The Anatomical Record. 304 (1): 42–62. doi:10.1002/ar.24500. PMID 32869467. S2CID 221405496.

External links

[edit]- 3D cranium models of fossils of large canids (Canis lupus) from Goyet, Trou des Nutons and Trou Balleux, Belgium provides a download of data to see these specimens in 3D.

Bibliography

[edit]- Derr, Mark (2011). How the Dog Became the Dog: From Wolves to Our Best Friends. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-4683-0269-1.[permanent dead link]

- Pierotti, R.; Fogg, B. (2017). The First Domestication: How Wolves and Humans Coevolved. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22616-4.

- Shipman, P. (2015). The Invaders:How humans and their dogs drove Neanderthals to extinction. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-73676-4.

_Wolf.png/250px-Men_of_the_old_stone_age_(1915)_Wolf.png)

_Wolf.png)