Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Phyllosphere

View on Wikipedia

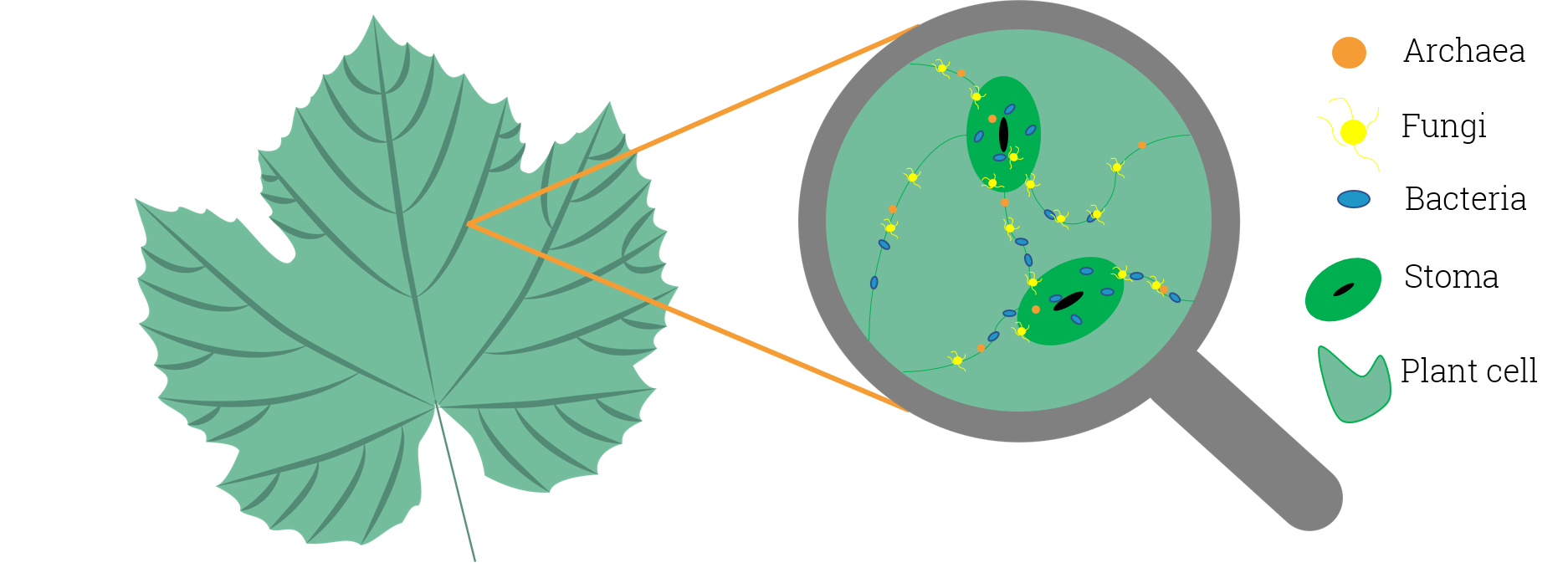

In microbiology, the phyllosphere is the total above-ground surface of a plant when viewed as a habitat for microorganisms.[1][2][3] The phyllosphere can be further subdivided into the caulosphere (stems), phylloplane (leaves), anthosphere (flowers), and carposphere (fruits). The below-ground microbial habitats (i.e. the thin-volume of soil surrounding root or subterranean stem surfaces) are referred to as the rhizosphere and laimosphere. Most plants host diverse communities of microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, archaea, and protists. Some are beneficial to the plant, while others function as plant pathogens and may damage the host plant or even kill it.

The phyllosphere microbiome

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Microbiomes |

|---|

|

The leaf surface, or phyllosphere, harbours a microbiome comprising diverse communities of bacteria, archaea, fungi, algae and viruses.[4][5] Microbial colonizers are subjected to diurnal and seasonal fluctuations of heat, moisture, and radiation. In addition, these environmental elements affect plant physiology (such as photosynthesis, respiration, water uptake etc.) and indirectly influence microbiome composition.[6] Rain and wind also cause temporal variation to the phyllosphere microbiome.[7]

The phyllosphere includes the total aerial (above-ground) surface of a plant, and as such includes the surface of the stem, flowers and fruit, but most particularly the leaf surfaces. Compared with the rhizosphere and the endosphere the phyllosphere is nutrient poor and its environment more dynamic.

Interactions between plants and their associated microorganisms in many of these microbiomes can play pivotal roles in host plant health, function, and evolution.[8] Interactions between the host plant and phyllosphere bacteria have the potential to drive various aspects of host plant physiology.[9][2][10] However, as of 2020 knowledge of these bacterial associations in the phyllosphere remains relatively modest, and there is a need to advance fundamental knowledge of phyllosphere microbiome dynamics.[11][12]

The assembly of the phyllosphere microbiome, which can be strictly defined as epiphytic bacterial communities on the leaf surface, can be shaped by the microbial communities present in the surrounding environment (i.e., stochastic colonisation) and the host plant (i.e., biotic selection).[4][13][12] However, although the leaf surface is generally considered a discrete microbial habitat,[14][15] there is no consensus on the dominant driver of community assembly across phyllosphere microbiomes. For example, host-specific bacterial communities have been reported in the phyllosphere of co-occurring plant species, suggesting a dominant role of host selection.[15][16][17][12]

Conversely, microbiomes of the surrounding environment have also been reported to be the primary determinant of phyllosphere community composition.[14][18][19][20] As a result, the processes that drive phyllosphere community assembly are not well understood but unlikely to be universal across plant species. However, the existing evidence does indicate that phyllosphere microbiomes exhibiting host-specific associations are more likely to interact with the host than those primarily recruited from the surrounding environment.[9][21][22][23][12]

Overall, there remains high species richness in phyllosphere communities. Fungal communities are highly variable in the phyllosphere of temperate regions and are more diverse than in tropical regions.[25] There can be up to 107 microbes per square centimetre present on the leaf surfaces of plants, and the bacterial population of the phyllosphere on a global scale is estimated to be 1026 cells.[26] The population size of the fungal phyllosphere is likely to be smaller.[27]

Phyllosphere microbes from different plants appear to be somewhat similar at high levels of taxa, but at the lower levels taxa there remain significant differences. This indicates microorganisms may need finely tuned metabolic adjustment to survive in phyllosphere environment.[25] Pseudomonadota seems to be the dominant colonizers, with Bacteroidota and Actinomycetota also predominant in phyllospheres.[28] Although there are similarities between the rhizosphere and soil microbial communities, very little similarity has been found between phyllosphere communities and microorganisms floating in open air (aeroplankton).[29][6]

The search for a core microbiome in host-associated microbial communities is a useful first step in trying to understand the interactions that may be occurring between a host and its microbiome.[30][31] The prevailing core microbiome concept is built on the notion that the persistence of a taxon across the spatiotemporal boundaries of an ecological niche is directly reflective of its functional importance within the niche it occupies; it therefore provides a framework for identifying functionally critical microorganisms that consistently associate with a host species.[30][32][33][12]

Divergent definitions of "core microbiome" have arisen across scientific literature with researchers variably identifying "core taxa" as those persistent across distinct host microhabitats [35][36] and even different species.[17][21] Given the functional divergence of microorganisms across different host species [17] and microhabitats,[37] defining core taxa sensu stricto as those persistent across broad geographic distances within tissue- and species-specific host microbiomes, represents the most biologically and ecologically appropriate application of this conceptual framework.[38][12] Tissue- and species-specific core microbiomes across host populations separated by broad geographical distances have not been widely reported for the phyllosphere using the stringent definition established by Ruinen.[2][12]

Example: The manuka phyllosphere

[edit]The flowering tea tree commonly known as manuka is indigenous to New Zealand.[39] Manuka honey, produced from the nectar of manuka flowers, is known for its non-peroxide antibacterial properties.[40][41] These non-peroxide antibacterial properties have been principally linked to the accumulation of the three-carbon sugar dihydroxyacetone (DHA) in the nectar of the manuka flower, which undergoes a chemical conversion to methylglyoxal (MGO) in mature honey.[42][43][44] However, the concentration of DHA in the nectar of manuka flowers is notoriously variable, and the antimicrobial efficacy of manuka honey consequently varies from region to region and from year to year.[45][46][47] Despite extensive research efforts, no reliable correlation has been identified between DHA production and climatic,[48] edaphic,[49] or host genetic factors.[50][12]

(B) The chart on the right shows how OTUs in phyllosphere and associated soil communities differed in relative abundances.[12]

Microorganisms have been studied in the manuka rhizosphere and endosphere.[51][52][53] Earlier studies primarily focussed on fungi, and a 2016 study provided the first investigation of endophytic bacterial communities from three geographically and environmentally distinct manuka populations using fingerprinting techniques and revealed tissue-specific core endomicrobiomes.[54][12] A 2020 study identified a habitat-specific and relatively abundant core microbiome in the manuka phyllosphere, which was persistent across all samples. In contrast, non-core phyllosphere microorganisms exhibited significant variation across individual host trees and populations that was strongly driven by environmental and spatial factors. The results demonstrated the existence of a dominant and ubiquitous core microbiome in the phyllosphere of manuka.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Last, F.T. (1955). "Seasonal incidence of Sporobolomyces on cereal leaves". Trans Br Mycol Soc. 38 (3): 221–239. doi:10.1016/s0007-1536(55)80069-1.

- ^ a b c Cid, Fernanda P.; Maruyama, Fumito; Murase, Kazunori; Graether, Steffen P.; Larama, Giovanni; Bravo, Leon A.; Jorquera, Milko A. (2018). "Draft genome sequences of bacteria isolated from the Deschampsia antarctica phyllosphere". Extremophiles. 22 (3): 537–552. doi:10.1007/s00792-018-1015-x. PMID 29492666. S2CID 4320165.

- ^ Leveau, Johan H.J. (2006) "Microbial communities in the phyllosphere". In: Riederer M. and Müller C. (Eds) Biology of the Plant Cuticle, chapter 11, pages 334–367.

- ^ a b Leveau, Johan HJ (2019). "A brief from the leaf: Latest research to inform our understanding of the phyllosphere microbiome". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 49: 41–49. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2019.10.002. PMID 31707206. S2CID 207946690.

- ^ Ruinen, J. (1956) "Occurrence of Beijerinckia species in the 'phyllosphere'". Nature, 177(4501): 220–221.

- ^ a b Dastogeer, K.M., Tumpa, F.H., Sultana, A., Akter, M.A. and Chakraborty, A. (2020) "Plant microbiome–an account of the factors that shape community composition and diversity". Current Plant Biology: 100161. doi:10.1016/j.cpb.2020.100161.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Lindow, Steven E. (1996). "Role of Immigration and Other Processes in Determining Epiphytic Bacterial Populations". Aerial Plant Surface Microbiology. pp. 155–168. doi:10.1007/978-0-585-34164-4_10. ISBN 978-0-306-45382-3.

- ^ Friesen, Maren L.; Porter, Stephanie S.; Stark, Scott C.; von Wettberg, Eric J.; Sachs, Joel L.; Martinez-Romero, Esperanza (2011). "Microbially Mediated Plant Functional Traits". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 42: 23–46. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145039.

- ^ a b Vogel, Christine; Bodenhausen, Natacha; Gruissem, Wilhelm; Vorholt, Julia A. (2016). "The Arabidopsis leaf transcriptome reveals distinct but also overlapping responses to colonization by phyllosphere commensals and pathogen infection with impact on plant health" (PDF). New Phytologist. 212 (1): 192–207. Bibcode:2016NewPh.212..192V. doi:10.1111/nph.14036. hdl:20.500.11850/117578. PMID 27306148.

- ^ Kumaravel, Sowmya; Thankappan, Sugitha; Raghupathi, Sridar; Uthandi, Sivakumar (2018). "Draft Genome Sequence of Plant Growth-Promoting and Drought-Tolerant Bacillus altitudinis FD48, Isolated from Rice Phylloplane". Genome Announcements. 6 (9). doi:10.1128/genomeA.00019-18. PMC 5834328. PMID 29496824.

- ^ Laforest-Lapointe, Isabelle; Whitaker, Briana K. (2019). "Decrypting the phyllosphere microbiota: Progress and challenges". American Journal of Botany. 106 (2): 171–173. doi:10.1002/ajb2.1229. PMID 30726571.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Noble, Anya S.; Noe, Stevie; Clearwater, Michael J.; Lee, Charles K. (2020). "A core phyllosphere microbiome exists across distant populations of a tree species indigenous to New Zealand". PLOS ONE. 15 (8) e0237079. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1537079N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237079. PMC 7425925. PMID 32790769.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.  Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ Vorholt, Julia A. (2012). "Microbial life in the phyllosphere". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 10 (12): 828–840. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2910. hdl:20.500.11850/59727. PMID 23154261. S2CID 10447146.

- ^ a b Stone, Bram W. G.; Jackson, Colin R. (2016). "Biogeographic Patterns Between Bacterial Phyllosphere Communities of the Southern Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) in a Small Forest". Microbial Ecology. 71 (4): 954–961. Bibcode:2016MicEc..71..954S. doi:10.1007/s00248-016-0738-4. PMID 26883131. S2CID 17292307.

- ^ a b Redford, Amanda J.; Bowers, Robert M.; Knight, Rob; Linhart, Yan; Fierer, Noah (2010). "The ecology of the phyllosphere: Geographic and phylogenetic variability in the distribution of bacteria on tree leaves". Environmental Microbiology. 12 (11): 2885–2893. Bibcode:2010EnvMi..12.2885R. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02258.x. PMC 3156554. PMID 20545741.

- ^ Vokou, Despoina; Vareli, Katerina; Zarali, Ekaterini; Karamanoli, Katerina; Constantinidou, Helen-Isis A.; Monokrousos, Nikolaos; Halley, John M.; Sainis, Ioannis (2012). "Exploring Biodiversity in the Bacterial Community of the Mediterranean Phyllosphere and its Relationship with Airborne Bacteria". Microbial Ecology. 64 (3): 714–724. Bibcode:2012MicEc..64..714V. doi:10.1007/s00248-012-0053-7. PMID 22544345. S2CID 17291303.

- ^ a b c Laforest-Lapointe, Isabelle; Messier, Christian; Kembel, Steven W. (2016). "Host species identity, site and time drive temperate tree phyllosphere bacterial community structure". Microbiome. 4 (1): 27. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0174-1. PMC 4912770. PMID 27316353.

- ^ Zarraonaindia, Iratxe; Owens, Sarah M.; Weisenhorn, Pamela; West, Kristin; Hampton-Marcell, Jarrad; Lax, Simon; Bokulich, Nicholas A.; Mills, David A.; Martin, Gilles; Taghavi, Safiyh; Van Der Lelie, Daniel; Gilbert, Jack A. (2015). "The Soil Microbiome Influences Grapevine-Associated Microbiota". mBio. 6 (2). doi:10.1128/mBio.02527-14. PMC 4453523. PMID 25805735.

- ^ Finkel, Omri M.; Burch, Adrien Y.; Lindow, Steven E.; Post, Anton F.; Belkin, Shimshon (2011). "Geographical Location Determines the Population Structure in Phyllosphere Microbial Communities of a Salt-Excreting Desert Tree". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 77 (21): 7647–7655. Bibcode:2011ApEnM..77.7647F. doi:10.1128/AEM.05565-11. PMC 3209174. PMID 21926212.

- ^ Finkel, Omri M.; Burch, Adrien Y.; Elad, Tal; Huse, Susan M.; Lindow, Steven E.; Post, Anton F.; Belkin, Shimshon (2012). "Distance-Decay Relationships Partially Determine Diversity Patterns of Phyllosphere Bacteria on Tamrix Trees across the Sonoran Desert". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 78 (17): 6187–6193. Bibcode:2012ApEnM..78.6187F. doi:10.1128/AEM.00888-12. PMC 3416633. PMID 22752165.

- ^ a b Kembel, S. W.; O'Connor, T. K.; Arnold, H. K.; Hubbell, S. P.; Wright, S. J.; Green, J. L. (2014). "Relationships between phyllosphere bacterial communities and plant functional traits in a neotropical forest". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (38): 13715–13720. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11113715K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1216057111. PMC 4183302. PMID 25225376. S2CID 852584.

- ^ Innerebner, Gerd; Knief, Claudia; Vorholt, Julia A. (2011). "Protection of Arabidopsis thaliana against Leaf-Pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae by Sphingomonas Strains in a Controlled Model System". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 77 (10): 3202–3210. Bibcode:2011ApEnM..77.3202I. doi:10.1128/AEM.00133-11. PMC 3126462. PMID 21421777.

- ^ Lajoie, Geneviève; Maglione, Rémi; Kembel, Steven W. (2020). "Adaptive matching between phyllosphere bacteria and their tree hosts in a neotropical forest". Microbiome. 8 (1): 70. doi:10.1186/s40168-020-00844-7. PMC 7243311. PMID 32438916.

- ^ Compant, Stéphane; Cambon, Marine C.; Vacher, Corinne; Mitter, Birgit; Samad, Abdul; Sessitsch, Angela (2020). "The plant endosphere world – bacterial life within plants". Environmental Microbiology. 23 (4): 1812–1829. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.15240. ISSN 1462-2912. PMID 32955144.

- ^ a b Finkel, Omri M.; Burch, Adrien Y.; Lindow, Steven E.; Post, Anton F.; Belkin, Shimshon (2011). "Geographical Location Determines the Population Structure in Phyllosphere Microbial Communities of a Salt-Excreting Desert Tree". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 77 (21): 7647–7655. Bibcode:2011ApEnM..77.7647F. doi:10.1128/AEM.05565-11. PMC 3209174. PMID 21926212.

- ^ Vorholt, Julia A. (2012). "Microbial life in the phyllosphere". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 10 (12): 828–840. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2910. hdl:20.500.11850/59727. PMID 23154261. S2CID 10447146.

- ^ Lindow, Steven E.; Brandl, Maria T. (2003). "Microbiology of the Phyllosphere". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 69 (4): 1875–1883. Bibcode:2003ApEnM..69.1875L. doi:10.1128/AEM.69.4.1875-1883.2003. PMC 154815. PMID 12676659. S2CID 2304379.

- ^ Bodenhausen, Natacha; Horton, Matthew W.; Bergelson, Joy (2013). "Bacterial Communities Associated with the Leaves and the Roots of Arabidopsis thaliana". PLOS ONE. 8 (2) e56329. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...856329B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056329. PMC 3574144. PMID 23457551.

- ^ Vokou, Despoina; Vareli, Katerina; Zarali, Ekaterini; Karamanoli, Katerina; Constantinidou, Helen-Isis A.; Monokrousos, Nikolaos; Halley, John M.; Sainis, Ioannis (2012). "Exploring Biodiversity in the Bacterial Community of the Mediterranean Phyllosphere and its Relationship with Airborne Bacteria". Microbial Ecology. 64 (3): 714–724. Bibcode:2012MicEc..64..714V. doi:10.1007/s00248-012-0053-7. PMID 22544345. S2CID 17291303.

- ^ a b Shade, Ashley; Handelsman, Jo (2012). "Beyond the Venn diagram: The hunt for a core microbiome". Environmental Microbiology. 14 (1): 4–12. Bibcode:2012EnvMi..14....4S. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02585.x. PMID 22004523.

- ^ Berg, Gabriele; Rybakova, Daria; Fischer, Doreen; Cernava, Tomislav; Vergès, Marie-Christine Champomier; Charles, Trevor; Chen, Xiaoyulong; Cocolin, Luca; Eversole, Kellye; Corral, Gema Herrero; Kazou, Maria; Kinkel, Linda; Lange, Lene; Lima, Nelson; Loy, Alexander; MacKlin, James A.; Maguin, Emmanuelle; Mauchline, Tim; McClure, Ryan; Mitter, Birgit; Ryan, Matthew; Sarand, Inga; Smidt, Hauke; Schelkle, Bettina; Roume, Hugo; Kiran, G. Seghal; Selvin, Joseph; Souza, Rafael Soares Correa de; Van Overbeek, Leo; et al. (2020). "Microbiome definition re-visited: Old concepts and new challenges". Microbiome. 8 (1): 103. doi:10.1186/s40168-020-00875-0. PMC 7329523. PMID 32605663.

- ^ Turnbaugh, Peter J.; Hamady, Micah; Yatsunenko, Tanya; Cantarel, Brandi L.; Duncan, Alexis; Ley, Ruth E.; Sogin, Mitchell L.; Jones, William J.; Roe, Bruce A.; Affourtit, Jason P.; Egholm, Michael; Henrissat, Bernard; Heath, Andrew C.; Knight, Rob; Gordon, Jeffrey I. (2009). "A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins". Nature. 457 (7228): 480–484. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..480T. doi:10.1038/nature07540. PMC 2677729. PMID 19043404.

- ^ Lundberg, Derek S.; Lebeis, Sarah L.; Paredes, Sur Herrera; Yourstone, Scott; Gehring, Jase; Malfatti, Stephanie; Tremblay, Julien; Engelbrektson, Anna; Kunin, Victor; Rio, Tijana Glavina del; Edgar, Robert C.; Eickhorst, Thilo; Ley, Ruth E.; Hugenholtz, Philip; Tringe, Susannah Green; Dangl, Jeffery L. (2012). "Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome". Nature. 488 (7409): 86–90. Bibcode:2012Natur.488...86L. doi:10.1038/nature11237. PMC 4074413. PMID 22859206.

- ^ He, Sheng Yang (2020) When plants and their microbes are not in sync, the results can be disastrous The Conversation, 28 August 2020.

- ^ Hamonts, Kelly; Trivedi, Pankaj; Garg, Anshu; Janitz, Caroline; Grinyer, Jasmine; Holford, Paul; Botha, Frederik C.; Anderson, Ian C.; Singh, Brajesh K. (2018). "Field study reveals core plant microbiota and relative importance of their drivers". Environmental Microbiology. 20 (1): 124–140. Bibcode:2018EnvMi..20..124H. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.14031. PMID 29266641. S2CID 10650949.

- ^ Cernava, Tomislav; Erlacher, Armin; Soh, Jung; Sensen, Christoph W.; Grube, Martin; Berg, Gabriele (2019). "Enterobacteriaceae dominate the core microbiome and contribute to the resistome of arugula (Eruca sativa Mill.)". Microbiome. 7 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/s40168-019-0624-7. PMC 6352427. PMID 30696492.

- ^ Leff, Jonathan W.; Del Tredici, Peter; Friedman, William E.; Fierer, Noah (2015). "Spatial structuring of bacterial communities within individual Ginkgo bilobatrees". Environmental Microbiology. 17 (7): 2352–2361. Bibcode:2015EnvMi..17.2352L. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12695. PMID 25367625.

- ^ Hernandez-Agreda, Alejandra; Gates, Ruth D.; Ainsworth, Tracy D. (2017). "Defining the Core Microbiome in Corals' Microbial Soup". Trends in Microbiology. 25 (2): 125–140. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.11.003. PMID 27919551.

- ^ Stephens, J. M. C.; Molan, P. C.; Clarkson, B. D. (2005). "A review of Leptospermum scoparium(Myrtaceae) in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 43 (2): 431–449. Bibcode:2005NZJB...43..431S. doi:10.1080/0028825X.2005.9512966. S2CID 53515334.

- ^ Cooper, R.A.; Molan, P.C.; Harding, K.G. (2002). "The sensitivity to honey of Gram-positive cocci of clinical significance isolated from wounds". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 93 (5): 857–863. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01761.x. PMID 12392533. S2CID 24517001.

- ^ Rabie, Erika; Serem, June Cheptoo; Oberholzer, Hester Magdalena; Gaspar, Anabella Regina Marques; Bester, Megan Jean (2016). "How methylglyoxal kills bacteria: An ultrastructural study". Ultrastructural Pathology. 40 (2): 107–111. doi:10.3109/01913123.2016.1154914. hdl:2263/52156. PMID 26986806. S2CID 13372064.

- ^ Adams, Christopher J.; Manley-Harris, Merilyn; Molan, Peter C. (2009). "The origin of methylglyoxal in New Zealand manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) honey". Carbohydrate Research. 344 (8): 1050–1053. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2009.03.020. PMID 19368902.

- ^ Atrott, Julia; Haberlau, Steffi; Henle, Thomas (2012). "Studies on the formation of methylglyoxal from dihydroxyacetone in Manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) honey". Carbohydrate Research. 361: 7–11. doi:10.1016/j.carres.2012.07.025. PMID 22960208.

- ^ Mavric, Elvira; Wittmann, Silvia; Barth, Gerold; Henle, Thomas (2008). "Identification and quantification of methylglyoxal as the dominant antibacterial constituent of Manuka (Leptospermum scoparium)honeys from New Zealand". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 52 (4): 483–489. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200700282. PMID 18210383.

- ^ Hamilton, G., Millner, J., Robertson, A. and Stephens, J. (2013) "Assessment of manuka provenances for production of high 'unique manuka factor' honey". Agronomy New Zealand, 43: 139–144.

- ^ Williams, Simon; King, Jessica; Revell, Maria; Manley-Harris, Merilyn; Balks, Megan; Janusch, Franziska; Kiefer, Michael; Clearwater, Michael; Brooks, Peter; Dawson, Murray (2014). "Regional, Annual, and Individual Variations in the Dihydroxyacetone Content of the Nectar of Ma̅nuka (Leptospermum scoparium) in New Zealand". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 62 (42): 10332–10340. Bibcode:2014JAFC...6210332W. doi:10.1021/jf5045958. PMID 25277074.

- ^ Stephens, J.M.C. (2006) "The factors responsible for the varying levels of UMF® in manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) honey", Doctoral dissertation, University of Waikato.

- ^ Noe, Stevie; Manley-Harris, Merilyn; Clearwater, Michael J. (2019). "Floral nectar of wild manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) varies more among plants than among sites". New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science. 47 (4): 282–296. Bibcode:2019NZJCH..47..282N. doi:10.1080/01140671.2019.1670681. S2CID 204143940.

- ^ Nickless, Elizabeth M.; Anderson, Christopher W. N.; Hamilton, Georgie; Stephens, Jonathan M.; Wargent, Jason (2017). "Soil influences on plant growth, floral density and nectar yield in three cultivars of manuka (Leptospermum scoparium)". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 55 (2): 100–117. Bibcode:2017NZJB...55..100N. doi:10.1080/0028825X.2016.1247732. S2CID 88657399.

- ^ Clearwater, Michael J.; Revell, Maria; Noe, Stevie; Manley-Harris, Merilyn (2018). "Influence of genotype, floral stage, and water stress on floral nectar yield and composition of manuka (Leptospermum scoparium)". Annals of Botany. 121 (3): 501–512. doi:10.1093/aob/mcx183. PMC 5838834. PMID 29300875.

- ^ Johnston, Peter R. (1998). "Leaf endophytes of manuka (Leptospermum scoparium)". Mycological Research. 102 (8): 1009–1016. doi:10.1017/S0953756297005765.

- ^ McKenzie, E. H. C.; Johnston, P. R.; Buchanan, P. K. (2006). "Checklist of fungi on teatree (Kunzeaand Leptospermumspecies) in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 44 (3): 293–335. Bibcode:2006NZJB...44..293M. doi:10.1080/0028825X.2006.9513025. S2CID 84538904.

- ^ Wicaksono, Wisnu Adi; Sansom, Catherine E.; Eirian Jones, E.; Perry, Nigel B.; Monk, Jana; Ridgway, Hayley J. (2018). "Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associated with Leptospermum scoparium (Manuka): Effects on plant growth and essential oil content". Symbiosis. 75 (1): 39–50. Bibcode:2018Symbi..75...39W. doi:10.1007/s13199-017-0506-3. S2CID 4819178.

- ^ Wicaksono, Wisnu Adi; Jones, E. Eirian; Monk, Jana; Ridgway, Hayley J. (2016). "The Bacterial Signature of Leptospermum scoparium (Manuka) Reveals Core and Accessory Communities with Bioactive Properties". PLOS ONE. 11 (9) e0163717. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1163717W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163717. PMC 5038978. PMID 27676607.