Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stacking (chemistry)

View on WikipediaIn chemistry, stacking refers to superposition of molecules or atomic sheets owing to attractive interactions between these molecules or sheets.

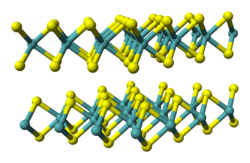

Metal dichalcogenide compounds

[edit]

Metal dichalcogenides have the formula ME2, where M = a transition metal and E = S, Se, Te.[1] In terms of their electronic structures, these compounds are usually viewed as derivatives of M4+. They adopt stacked structures, which is relevant to their ability to undergo intercalation, e.g. by lithium, and their lubricating properties. The corresponding diselenides and even ditellurides are known, e.g., TiSe2, MoSe2, and WSe2.

Charge transfer salts

[edit]

A combination of tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ) and tetrathiafulvalene (TTF) forms a strong charge-transfer complex referred to as TTF-TCNQ.[3] The solid shows almost metallic electrical conductance. In a TTF-TCNQ crystal, TTF and TCNQ molecules are arranged independently in separate parallel-aligned stacks, and an electron transfer occurs from donor (TTF) to acceptor (TCNQ) stacks.[4]

Graphite

[edit]

Graphite consists of stacked sheets of covalently bonded carbon.[5][6] The individual layers are called graphene. In each layer, each carbon atom is bonded to three other atoms forming a continuous layer of sp2 bonded carbon hexagons, like a honeycomb lattice with a bond length of 0.142 nm, and the distance between planes is 0.335 nm.[7] Bonding between layers is relatively weak van der Waals bonds, which allows the graphene-like layers to be easily separated and to glide past each other.[8] Electrical conductivity perpendicular to the layers is consequently about 1000 times lower.[9]

Linear chain compounds

[edit]Linear chain compounds are materials composed of stacked arrays of metal-metal bonded molecules or ions. Such materials exhibit anisotropic electrical conductivity.[10] One example is Rh(acac)(CO)2 (acac = acetylacetonate, which stack with Rh···Rh distances of about 326 pm.[11] Classic examples include Krogmann's salt and Magnus's green salt.

Counterexample: benzene dimer and related species

[edit]π–π stacking is a noncovalent interaction between the pi bonds of aromatic rings.[12] Such "sandwich interactions" are however generally electrostatically repulsive. What is more commonly observed are either a staggered stacking (parallel displaced) or pi-teeing (perpendicular T-shaped) interaction both of which are electrostatic attractive.[13] For example, the most commonly observed interactions between aromatic rings of amino acid residues in proteins is a staggered stacked followed by a perpendicular orientation. Sandwiched orientations are relatively rare.[14] Pi stacking is repulsive as it places carbon atoms with partial negative charges from one ring on top of other partial negatively charged carbon atoms from the second ring and hydrogen atoms with partial positive charges on top of other hydrogen atoms that likewise carry partial positive charges.[15]

π–π interactions play a role in supramolecular chemistry, specifically the synthesis of catenane. The major challenge for the synthesis of catenane is to interlock molecules in a controlled fashion. Attractive π–π interactions exist between electron-rich benzene derivatives and electron-poor pyridinium rings.[16] [2]Catanene was synthesized by treating bis(pyridinium) (A), bisparaphenylene-34-crown-10 (B), and 1, 4-bis(bromomethyl)benzene (C) (Fig. 2). The π–π interaction between A and B directed the formation of an interlocked template intermediate that was further cyclized by substitution reaction with compound C to generate the [2]catenane product.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wells, A.F. (1984) Structural Inorganic Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-855370-6.

- ^ D. Chasseau; G. Comberton; J. Gaultier; C. Hauw (1978). "Réexamen de la structure du complexe hexaméthylène-tétrathiafulvalène-tétracyanoquinodiméthane". Acta Crystallographica Section B. 34 (2): 689. Bibcode:1978AcCrB..34..689C. doi:10.1107/S0567740878003830.

- ^ P. W. Anderson; P. A. Lee; M. Saitoh (1973). "Remarks on giant conductivity in TTF-TCNQ". Solid State Communications. 13 (5): 595–598. Bibcode:1973SSCom..13..595A. doi:10.1016/S0038-1098(73)80020-1.

- ^ Van De Wouw, Heidi L.; Chamorro, Juan; Quintero, Michael; Klausen, Rebekka S. (2015). "Opposites Attract: Organic Charge Transfer Salts". Journal of Chemical Education. 92 (12): 2134–2139. Bibcode:2015JChEd..92.2134V. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00340.

- ^ Delhaes, Pierre (2000). "Polymorphism of carbon". In Delhaes, Pierre (ed.). Graphite and precursors. Gordon & Breach. pp. 1–24. ISBN 9789056992286.

- ^ Pierson, Hugh O. (2012). Handbook of carbon, graphite, diamond, and fullerenes : properties, processing, and applications. Noyes Publications. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9780815517399.

- ^ Delhaes, P. (2001). Graphite and Precursors. CRC Press. ISBN 978-90-5699-228-6.

- ^ Chung, D. D. L. (2002). "Review Graphite". Journal of Materials Science. 37 (8): 1475–1489. doi:10.1023/A:1014915307738. S2CID 189839788.

- ^ Pierson, Hugh O. (1993). Handbook of carbon, graphite, diamond, and fullerenes : properties, processing, and applications. Park Ridge, N.J.: Noyes Publications. ISBN 0-8155-1739-4. OCLC 49708274.

- ^ Bera, J. K.; Dunbar, K. R. (2002). "Chain Compounds Based on Transition Metal Backbones: New Life for an Old Topic". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41 (23): 4453–4457. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20021202)41:23<4453::AID-ANIE4453>3.0.CO;2-1. PMID 12458505.

- ^ Huq, Fazlul; Skapski, Andrzej C. (1974). "Refinement of the crystal structure of acetylacetonatodicarbonylrhodium(I)". J. Cryst. Mol. Struct. 4 (6): 411–418. doi:10.1007/BF01220097. S2CID 96977904.

- ^ Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, p. 114, ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1

- ^ Lewis M, Bagwill C, Hardebeck L, Wireduaah S (2016). "Modern Computational Approaches to Understanding Interactions of Aromatics". In Johnson DW, Hof F (eds.). Aromatic Interactions: Frontiers in Knowledge and Application. England: Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-1-78262-662-6.

- ^ McGaughey GB, Gagné M, Rappé AK (June 1998). "pi-Stacking interactions. Alive and well in proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (25): 15458–63. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.25.15458. PMID 9624131.

- ^ Martinez CR, Iverson BL (2012). "Rethinking the term "pi-stacking"". Chemical Science. 3 (7): 2191. doi:10.1039/c2sc20045g. hdl:2152/41033. ISSN 2041-6520. S2CID 95789541.

- ^ Ashton PR, Goodnow TT, Kaifer AE, Reddington MV, Slawin AM, Spencer N, et al. (1989). "A [2] Catenane Made to Order". J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 28 (10): 1396–1399. doi:10.1002/anie.198913961.

External links

[edit]- Luo R, Gilson HS, Potter MJ, Gilson MK (January 2001). "The physical basis of nucleic acid base stacking in water". Biophysical Journal. 80 (1): 140–148. Bibcode:2001BpJ....80..140L. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76001-8. PMC 1301220. PMID 11159389.

- Larry Wolf (2011): π-π (π-Stacking) interactions: origin and modulation

Stacking (chemistry)

View on GrokipediaPrinciples of Stacking Interactions

Definition and Overview

In chemistry, stacking refers to the parallel or near-parallel superposition of pi-conjugated molecular systems or atomic layers, resulting in extended structures such as crystalline lattices, layered materials, or supramolecular assemblies.[6] These interactions arise from weak noncovalent forces that align planar units to maximize attractive contributions while minimizing steric repulsion.[6] Stacking is a fundamental motif in both inorganic and organic systems, enabling properties like electrical conductivity in materials or stability in biological macromolecules. The historical development of stacking concepts traces back to early X-ray crystallographic studies, with the layered structure of graphite first elucidated by Bernal in 1924, revealing stacked hexagonal sheets of carbon atoms held by weak interlayer forces. Similar stacking arrangements were observed in aromatic compounds, such as hexamethylbenzene, by Lonsdale in 1929, highlighting short interplanar spacings between planar rings. Theoretical underpinnings emerged in 1930 with Fritz London's quantum mechanical description of dispersion forces, which provided the basis for understanding the attractive components in such layered configurations. Further advancements in the mid-20th century, through crystallographic analyses of aromatic crystals, solidified the recognition of pi-pi interactions as key drivers of these structures. Basic terminology distinguishes between parallel displaced stacking, where pi systems overlap offset to reduce Pauli repulsion, and edge-to-face configurations, where one ring's edge approaches the face of another at an angle.[6] Typical interlayer distances for pi-pi stacking fall in the range of 3.0-3.5 Å, reflecting a balance of attraction and repulsion.[6] These phenomena presuppose familiarity with van der Waals forces, including dispersion, and the delocalization of pi electrons in conjugated frameworks, which enhance orbital overlap and electron correlation effects. For example, graphite exemplifies atomic layer stacking, where carbon sheets align via these interactions to form a robust yet cleavable material.Intermolecular Forces Involved

The primary intermolecular forces responsible for stacking interactions in chemistry are non-covalent in nature, with London dispersion forces serving as the dominant contributor, particularly in pi-pi stacking between aromatic systems. These dispersion forces arise from correlated electron fluctuations between molecules, providing attractive interactions that stabilize parallel or slipped parallel geometries. Electrostatic interactions, primarily quadrupole-quadrupole attractions between the electron clouds of pi-systems, and induction effects, where one molecule polarizes the other, provide additional stabilization, though their contributions are typically smaller than dispersion. The overall stacking energy per interacting pair generally ranges from 2 to 10 kcal/mol, depending on the specific molecular systems and geometries involved.[2][7] In pi-pi stacking, the overlap of pi-orbitals between adjacent aromatic rings facilitates mutual polarization (induction), enhancing the attractive potential beyond simple van der Waals contacts via dispersion and electrostatic contributions. This orbital overlap modulates the electron density distribution, leading to a net stabilization that favors face-to-face or offset arrangements. The dispersion component of the interaction energy can be approximated by the London formula: where is the dispersion coefficient specific to the interacting pairs, and is the intermolecular distance between the centers of the pi-systems. This term captures the inverse-sixth-power dependence characteristic of dispersion forces, with higher-order terms like contributing at closer ranges.[8][9][10] Stacking interactions are particularly favored in non-polar environments, where solvation effects are minimal, allowing the hydrophobic effect and reduced solvent competition to enhance stability. In polar solvents, such as water, solvation shells around aromatic rings weaken pi-pi attractions by solvating the pi-electrons, thereby reducing the net binding energy. Entropy plays a key role in stack formation, as the release of ordered solvent molecules upon stacking contributes positively to the free energy change, though increased temperature generally destabilizes stacks by favoring disordered states and increasing vibrational entropy penalties.[11][12][13] Recent advances in the 2020s have improved computational modeling of stacking geometries through density functional theory (DFT) incorporating dispersion corrections, such as the Grimme D3 method, which accurately accounts for long-range electron correlation effects. These approaches, often combined with machine learning potentials for high-accuracy predictions, enable reliable simulation of stack stabilities and geometries in complex systems, as demonstrated in post-2020 studies on aromatic aggregates and layered structures. For instance, D3-corrected DFT has been used to predict slip-stacked configurations with errors below 1 kcal/mol compared to benchmark quantum chemical data.[14][15][16]Stacking in Layered Inorganic Materials

Graphite

Graphite exemplifies stacking interactions in carbon-based layered materials, featuring infinite stacks of graphene sheets composed of sp²-hybridized carbon atoms in a honeycomb lattice. The intralayer C-C bond length measures 0.142 nm, contributing to the robust in-plane structure, while the interlayer distance is 0.335 nm, reflecting the loose packing of adjacent sheets.[17][18] Interlayer bonding in graphite arises solely from weak van der Waals forces, lacking any covalent connections, which permits facile shear deformation and sliding between layers. This weak interaction facilitates mechanical exfoliation, as demonstrated by repeatedly peeling graphite with adhesive tape to isolate single-layer graphene sheets.[19] The resulting low shear strength underpins graphite's utility as a solid lubricant, where interlayer sliding minimizes friction in applications like high-pressure contacts.[20] The van der Waals stacking imparts pronounced anisotropy to graphite's properties, with in-plane electrical conductivity reaching approximately 2.5 × 10⁴ S/cm due to delocalized π electrons, contrasted by perpendicular conductivity of about 10 S/cm—a roughly 2500-fold difference stemming from the insulating interlayer gaps. Thermal conductivity exhibits similar anisotropy, with in-plane values exceeding 2000 W/m·K and out-of-plane around 10 W/m·K, enabling directional heat dissipation in composites.[21][22] As a precursor for graphene production, graphite undergoes mechanical or chemical exfoliation to yield high-quality 2D sheets for electronics and energy storage. Recent advances from 2020 to 2025 have leveraged stacked graphene derived from graphite in lithium-ion battery anodes, enhancing lithium intercalation capacity and cycling stability through surface modifications like coatings on natural graphite, achieving theoretical capacities near 372 mAh/g with improved rate performance.[23] This all-carbon stacking motif in graphite parallels layered structures in transition metal dichalcogenides but relies purely on π-π interactions without metal coordination.[24]Transition Metal Dichalcogenides

Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) are layered inorganic materials with the general formula ME₂, where M represents a transition metal such as molybdenum (Mo), tungsten (W), niobium (Nb), or tantalum (Ta), and E denotes a chalcogen atom like sulfur (S), selenium (Se), or tellurium (Te). Each layer adopts a sandwich-like X-M-X configuration, with the metal atom covalently bonded to six chalcogen atoms within the layer, while adjacent layers are bound exclusively by weak van der Waals interactions that facilitate sliding and stacking. This structure enables the materials to form stable bulk crystals with tunable interlayer registry, influencing their electronic and mechanical properties.[25][26] A key representative is molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂), which crystallizes in polytypes distinguished by their stacking sequences and coordination environments. In the common 2H polytype, Mo atoms adopt trigonal prismatic coordination, yielding hexagonal symmetry, whereas the 3R polytype features rhombohedral stacking with similar prismatic sites; an alternative 1T phase involves octahedral coordination and is metastable but catalytically active. The interlayer distance in bulk 2H-MoS₂ measures approximately 6.15 Å, reflecting the dominance of van der Waals forces that allow minimal overlap of electron clouds between layers. These polytypes arise from variations in the relative positioning of sulfur atoms across layers, such as AB or ABC sequences, which subtly modulate band structures without altering intralayer bonding.[27][28][29] TMDs exhibit semiconducting properties, with bulk forms showing indirect band gaps that transition to direct gaps in exfoliated monolayers, enhancing their optoelectronic potential. Synthesis typically involves chemical vapor deposition or mechanical/liquid-phase exfoliation from bulk precursors to yield atomically thin sheets, akin to methods used for other van der Waals materials. From 2021 to 2025, research on twisted bilayer TMDs, such as WSe₂ at small angles (e.g., 5°), has uncovered moiré superlattices that induce flat bands and unconventional superconductivity with critical temperatures up to 426 mK, driven by enhanced electron correlations in the moiré potential.[25][30][31] In applications, TMDs excel as solid lubricants owing to their low shear strength; for instance, MoS₂ coatings in aerospace components achieve friction coefficients below 0.05 in vacuum, resisting wear under high loads. As intercalation hosts in lithium-ion batteries, materials like MoS₂ accommodate Li⁺ ions between layers, causing expansion to ~10 Å spacing and enabling high-capacity anodes with reversible capacities exceeding 600 mAh/g, though phase transitions must be managed for stability. Furthermore, edge and defect sites in TMDs, particularly in the 1T phase of MoS₂, catalyze the hydrogen evolution reaction with overpotentials as low as 50 mV, positioning them as platinum alternatives in electrochemical water splitting.[32][33][34][35]Stacking in Organic and Coordination Compounds

Charge Transfer Salts

Charge transfer salts represent a class of organic molecular crystals where stacking interactions between π-conjugated donor and acceptor molecules facilitate partial electron transfer, resulting in enhanced electrical conductivity. In these systems, electron-rich donors, such as tetrathiafulvalene (TTF), and electron-poor acceptors, like 7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ), form segregated stacks rather than alternating mixed stacks, promoting metallic behavior through delocalized charge carriers. The partial charge transfer, typically denoted as δ ≈ 0.5–1 electron per donor-acceptor pair, creates mixed-valence states within the stacks, where the donor is partially oxidized (D^{δ+}) and the acceptor partially reduced (A^{δ-}), enabling band-like conduction along the stacking direction.[36] The prototypical example is TTF-TCNQ, a 1:1 charge transfer complex with the formula where δ ≈ 0.59.[36] In its crystal structure, TTF and TCNQ molecules form parallel π-stacked columns that are segregated, with interstack interactions providing weaker coupling. This arrangement leads to one-dimensional metallic conduction primarily along the stack axis, with room-temperature conductivity reaching approximately 10^3 S/cm.[37] At low temperatures, Peierls distortions occur on the TCNQ stacks around 53 K and on the TTF stacks near 38 K, causing a metal-to-insulator phase transition due to lattice dimerization and charge density wave formation.[38] These salts exhibit anisotropic transport properties, with conductivity confined largely to the stacking direction, highlighting the role of π-π stacking in mediating electron hopping. The partial charge transfer and mixed-valence character are key to avoiding full ionization, which would otherwise localize charges and promote insulating behavior. Discovered in the early 1970s, TTF-TCNQ marked the advent of organic metals and inspired subsequent research into highly conducting materials. In the 2020s, analogs of these charge transfer salts have been developed for organic superconductors, where modulation of the stacking arrangement tunes electronic correlations and enables superconductivity under pressure or doping.[39] This one-dimensional stacking motif in charge transfer salts shares conceptual similarities with linear chain compounds, emphasizing anisotropic conduction pathways.Linear Chain Compounds

Linear chain compounds in coordination chemistry feature one-dimensional stacking primarily through direct metal-metal bonds or π-π interactions between ligands, forming extended structures that exhibit unique electronic properties. These stacks often arise in square-planar d^8 metal complexes, where the overlap of d_{z^2} orbitals facilitates short metal-metal contacts, leading to chain-like arrangements in the solid state. For instance, in the rhodium(I) complex [Rh(acac)(CO)_2] (acac = acetylacetonate), the molecules form dimers with Rh···Rh distances of approximately 3.23 Å, which extend into chains through additional intermolecular interactions, exemplifying direct metal-metal bonding in stacking motifs.[40] A seminal example is Krogmann's salt, formulated as K_2[Pt(CN)4]Br{0.3}·3H_2O, discovered in the late 1960s, where square-planar Pt(II/III) units stack into infinite chains with short Pt-Pt distances of about 2.88 Å, significantly shorter than the sum of van der Waals radii, indicating strong d_{z^2}-d_{z^2} orbital overlap. This partial oxidation results in mixed-valence character, enabling metallic-like conductivity along the chain axis, with values up to 10^5 S/cm at room temperature, making it a prototype for one-dimensional conductors. Similarly, Magnus's green salt, [Pt(NH_3)_4][PtCl_4], first synthesized in 1831 but structurally characterized in modern times, features alternating [Pt(NH_3)_4]^{2+} and [PtCl_4]^{2-} units forming chains with alternating short (3.26 Å) and long (3.55 Å) Pt-Pt distances, reflecting its mixed-valence Pt(II)/Pt(IV) nature and semiconducting behavior.[41][42] These compounds display intense colors arising from intervalence charge transfer (IVCT) bands in the visible region, where electrons delocalize along the chain, as seen in the green hue of Magnus's salt due to Pt(IV) to Pt(II) transitions around 680 nm. Their semiconducting properties, with band gaps typically 0.1-0.5 eV, stem from Peierls distortions that open gaps in the nearly half-filled d_{z^2} band, yet allow anisotropic conductivity akin to molecular wires for potential use in nanoelectronics. Electron transfer mechanisms in these stacks parallel those in charge transfer salts but emphasize direct metal bonding over purely organic π-stacks.[42] Recent developments from 2020 onward have focused on synthesizing tunable 1D platinum chain compounds with modulated band gaps (0.5-2.0 eV) through ligand variations, enabling control over chain interactions for applications in spintronics, where spin-polarized transport along the chains could interface with magnetic layers. For example, solution-processable derivatives of Magnus-type salts have shown enhanced carrier mobilities up to 10 cm²/V·s, highlighting their promise as hybrid molecular components in spintronic devices.[43][42]Pi-Pi Stacking in Supramolecular and Biological Systems

Supramolecular Assemblies

In supramolecular chemistry, donor-acceptor π-π stacking interactions serve as a key non-covalent force for directing the self-assembly of molecular components into ordered architectures. These interactions arise from the overlap of π-electron clouds between electron-rich donors and electron-deficient acceptors, providing stabilization energies typically in the range of 5-15 kJ/mol per interaction, which balances strength and reversibility for dynamic systems.[44] This energy regime allows for precise control over assembly processes in solution, enabling the formation of pseudorotaxanes, catenanes, and other interlocked structures without requiring covalent bonds during initial templating. A seminal example is the template-directed synthesis of [45]catenanes developed by Fraser Stoddart and coworkers, where π-π stacking between electron-rich hydroquinone units within a crown ether macrocycle and the electron-poor tetracationic cyclobis(paraquat-p-phenylene) ring drives the formation of a pseudorotaxane complex. This non-covalent preorganization positions the components for subsequent ring-closing reactions, such as nucleophilic substitution, yielding the interlocked [45]catenane in high yields (up to 70%). The donor-acceptor charge-transfer complexation not only stabilizes the threading but also imparts a distinctive purple color to the assembly, highlighting the interaction's visibility and utility in synthetic design.[46] Beyond catenanes, π-π stacking underpins other supramolecular assemblies, such as the columnar phases in discotic liquid crystals, where disc-shaped aromatic cores align face-to-face to form one-dimensional π-stacked columns with hexagonal or rectangular ordering. These columns, stabilized by intermolecular π-π overlaps at distances of 3.3-3.5 Å, facilitate efficient charge transport and have been widely adopted in organic semiconductors and photovoltaic devices. Similarly, rotaxanes and molecular machines exploit π-π stacking for axle threading through macrocycles, enabling shuttling motions triggered by external stimuli like redox changes or light, as seen in bistable systems where stacking directs ring localization on specific recognition sites.[47][48] Recent advances from 2020 to 2025 have integrated tunable π-π interactions into metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) to optimize gas storage, particularly for methane and hydrogen. In flexible MOFs like those based on benzene-1,4-dicarboxylate linkers, interlayer π-π stacking modulates pore openness and adsorption sites, enhancing uptake capacities under ambient conditions through dynamic host-guest interactions. These developments leverage linker design to adjust stacking distances and strengths, improving selectivity and capacity in energy storage applications.[49]Biological Examples

In nucleic acids, π-π stacking interactions between the aromatic bases play a crucial role in stabilizing the double helical structure of DNA and RNA. These interactions occur between consecutive base pairs along the helix axis, contributing significantly to the overall thermal stability, often more than hydrogen bonding between complementary bases. For instance, base stacking accounts for approximately two-thirds of the duplex stability, with interaction energies typically ranging from 4 to 8 kcal/mol per stacked pair, enhanced by the hydrophobic effect that drives the nonpolar bases away from the aqueous environment.[50][51][50] Epigenetic modifications, such as the addition of a methyl group to cytosine forming 5-methylcytosine, further modulate these stacking interactions. The hydrophobic methyl substituent strengthens π-π stacking in CG:CG steps, increasing duplex stability and influencing gene expression patterns in chromatin.[52] In proteins, π-π stacking involving the aromatic side chains of phenylalanine (Phe), tyrosine (Tyr), and tryptophan (Trp) residues is prevalent in hydrophobic cores and active sites, promoting structural integrity and functional specificity. These interactions often adopt parallel displaced or T-shaped geometries, with Trp participating most frequently due to its large π-system. Additionally, π-π stacking can couple with cation-π interactions, where positively charged Arg or Lys side chains engage aromatic rings, as seen in enzyme-substrate binding pockets.[53][54][55] Beyond canonical structures, π-π stacking facilitates ligand recognition in RNA aptamers and enzyme active sites. In RNA aptamers, such as those binding flavins, the aromatic rings of nucleobases stack with ligand π-systems to enhance affinity and specificity. Similarly, in protein enzyme pockets, stacking interactions position substrates for catalysis, as exemplified in G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) where recent structural analyses reveal π-π contacts between ligands and residues like Tyr^{3.33}, influencing signaling bias toward G-protein or β-arrestin pathways.[56][57] Functionally, π-π stacking stabilizes secondary structures like α-helices and β-sheets in proteins and helices in nucleic acids, while also guiding folding kinetics by lowering energy barriers in compact intermediates. Disruptions, such as those from mutations altering aromatic residues, can destabilize folds and lead to diseases; for example, point mutations in lectins that break π-π stacks impair carbohydrate binding and cellular recognition. In nucleic acids, stacking defects from base modifications or lesions contribute to genomic instability in conditions like cancer.[58][59]Exceptions and Variations

Benzene Dimer Configurations

The benzene dimer serves as a prototypical model system for investigating π-π stacking interactions in aromatic compounds, revealing that parallel stacking is not the global energy minimum, contrary to initial expectations in early theoretical models. In this dimer, two benzene molecules interact via weak van der Waals forces, with binding energies on the order of 2-3 kcal/mol, making it an ideal case for high-level quantum chemical computations and gas-phase experiments. The potential energy surface features multiple local minima, highlighting the subtle balance between attractive dispersion forces and repulsive interactions that dictate preferred geometries.[60] The primary configurations include the parallel displaced (PD) structure, where the rings are offset by approximately 1.5-2 Å along the intermolecular axis, the T-shaped (edge-to-face) arrangement, and the sandwich (perfectly parallel) geometry. The PD configuration exhibits a binding energy of approximately 2.5 kcal/mol at an equilibrium vertical distance of ~3.8 Å between ring centers. The T-shaped structure, with one ring perpendicular to the other and the edge approaching the face at a C-H···π contact, is the global minimum with a slightly deeper binding energy of ~2.7 kcal/mol. In contrast, the sandwich configuration is unstable, acting as a saddle point on the potential energy surface due to strong Pauli repulsion from orbital overlap between the closely approaching π clouds, which outweighs the attractive dispersion at short distances.[61][62] Coupled-cluster calculations at the CCSD(T) level with complete basis set extrapolation provide the benchmark for these insights, demonstrating that the displacement in the PD geometry mitigates Pauli exclusion effects, thereby stabilizing it relative to the sandwich form despite similar dispersion contributions. These computations, performed in the early 2000s, refined earlier ab initio results and underscored the role of electron correlation in accurately capturing dispersion-dominated interactions.[60][61] This behavior of the benzene dimer explains why simple aromatic systems in supramolecular assemblies tend to avoid perfectly parallel stacks, favoring offset or perpendicular orientations to minimize steric and exchange repulsions while retaining π-π attraction. Historically, it served as a key counterexample to 1980s models of π-π interactions, such as those emphasizing charge-transfer or simple quadrupole attractions that predicted the parallel sandwich as the most stable, as evidenced by early SCF calculations overestimating its viability.[63][60] In the 2020s, gas-phase spectroscopic studies, including microwave and infrared techniques, have corroborated these computational energies and confirmed the near-degeneracy of PD and T-shaped minima in isolated clusters, with experimental binding energies aligning within 0.1-0.2 kcal/mol of CCSD(T) predictions. These findings reinforce the dimer's relevance to weakly bound aromatic clusters in atmospheric and interstellar chemistry.[62][64]Non-Parallel Stacking Modes

Non-parallel stacking modes in π-π interactions deviate from ideal face-to-face alignments, adopting geometries such as T-shaped, slipped-parallel, and herringbone arrangements to optimize energetic stability in molecular assemblies. These configurations arise primarily from the balance of dispersion forces, electrostatic interactions, and Pauli repulsion, allowing for effective packing in crystals and supramolecular structures while minimizing unfavorable overlaps.[7][65] The T-shaped mode, characterized by a 90° edge-to-face orientation where the edge of one aromatic ring aligns perpendicularly with the face of another, is prevalent in molecular crystals due to favorable quadrupolar electrostatics that stabilize the geometry despite reduced dispersion overlap.[7] Slipped-parallel stacking involves an offset displacement between nearly parallel rings, which alleviates steric repulsion from π-electron overlap while preserving significant dispersion attraction.[7] In polyaromatic hydrocarbons, the herringbone pattern emerges as a tilted, edge-to-face motif that combines CH-π hydrogen bonding with π-π contacts, promoting dense packing in crystalline lattices.[66] Representative examples illustrate these modes' roles in functional materials. In porphyrin assemblies, T-shaped stacking facilitates the formation of J-aggregates, where edge-to-face interactions, often augmented by metal-ligand coordination, enable cooperative assembly and enhanced excitonic coupling for optoelectronic applications.[67] Offset or slipped-parallel stacking in conducting polymers like polythiophene promotes efficient charge transport by optimizing intermolecular overlap, leading to improved crystallinity and conductivity in thin films.[68] Energetically, T-shaped interactions typically contribute 1-3 kcal/mol to binding, comparable to slipped-parallel modes, with the choice between them influenced by steric hindrance that favors offsets in crowded environments and dipole or quadrupole alignments that stabilize perpendicular orientations.[69] The benzene dimer exemplifies these preferences, exhibiting near-degenerate T-shaped and slipped energies as a foundational model.[70] Recent advances highlight non-parallel π-stacking's utility in advanced devices. In perovskite solar cells, slipped π-π stacked molecules have been employed to delay crystallization and anchor grain boundary defects, yielding efficient wide-bandgap devices with power conversion efficiencies exceeding 20% and enhanced stability.[71] For sensors, T-shaped and offset configurations enable selective binding in aromatic π-complexes, as demonstrated in 2025 studies using electron-deficient naphthalenes for detecting specific analytes via modulated π-π interactions.[72]References

- Aug 17, 2018 · Stacking interactions have been evaluated, employing computational methods, in dimers formed by analogous aliphatic and aromatic species of increasing size.