Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hyperbolic geometry

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2023) |

| Geometry |

|---|

|

| Geometers |

In mathematics, hyperbolic geometry (also called Lobachevskian geometry or Bolyai–Lobachevskian geometry) is a non-Euclidean geometry. The parallel postulate of Euclidean geometry is replaced with:

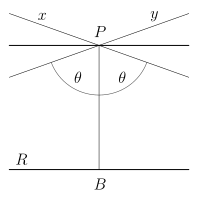

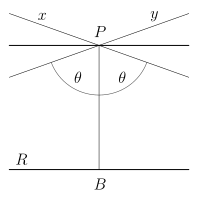

- For any given line R and point P not on R, in the plane containing both line R and point P there are at least two distinct lines through P that do not intersect R.

(Compare the above with Playfair's axiom, the modern version of Euclid's parallel postulate.)

The hyperbolic plane is a plane where every point is a saddle point. Hyperbolic plane geometry is also the geometry of pseudospherical surfaces, surfaces with a constant negative Gaussian curvature. Saddle surfaces have negative Gaussian curvature in at least some regions, where they locally resemble the hyperbolic plane.

The hyperboloid model of hyperbolic geometry provides a representation of events one temporal unit into the future in Minkowski space, the basis of special relativity. Each of these events corresponds to a rapidity in some direction.

When geometers first realised they were working with something other than the standard Euclidean geometry, they described their geometry under many different names; Felix Klein finally gave the subject the name hyperbolic geometry to include it in the now rarely used sequence elliptic geometry (spherical geometry), parabolic geometry (Euclidean geometry), and hyperbolic geometry. In the former Soviet Union, it is commonly called Lobachevskian geometry, named after one of its discoverers, the Russian geometer Nikolai Lobachevsky.

Properties

[edit]Relation to Euclidean geometry

[edit]

Hyperbolic geometry is more closely related to Euclidean geometry than it seems: the only axiomatic difference is the parallel postulate. When the parallel postulate is removed from Euclidean geometry the resulting geometry is absolute geometry. There are two kinds of absolute geometry, Euclidean and hyperbolic. All theorems of absolute geometry, including the first 28 propositions of book one of Euclid's Elements, are valid in Euclidean and hyperbolic geometry. Propositions 27 and 28 of Book One of Euclid's Elements prove the existence of parallel/non-intersecting lines.

This difference also has many consequences: concepts that are equivalent in Euclidean geometry are not equivalent in hyperbolic geometry; new concepts need to be introduced. Further, because of the angle of parallelism, hyperbolic geometry has an absolute scale, a relation between distance and angle measurements.

Lines

[edit]Single lines in hyperbolic geometry have exactly the same properties as single straight lines in Euclidean geometry. For example, two points uniquely define a line, and line segments can be infinitely extended.

Two intersecting lines have the same properties as two intersecting lines in Euclidean geometry. For example, two distinct lines can intersect in no more than one point, intersecting lines form equal opposite angles, and adjacent angles of intersecting lines are supplementary.

When a third line is introduced, then there can be properties of intersecting lines that differ from intersecting lines in Euclidean geometry. For example, given two intersecting lines there are infinitely many lines that do not intersect either of the given lines.

These properties are all independent of the model used, even if the lines may look radically different.

Non-intersecting / parallel lines

[edit]

Non-intersecting lines in hyperbolic geometry also have properties that differ from non-intersecting lines in Euclidean geometry:

- For any line R and any point P which does not lie on R, in the plane containing line R and point P there are at least two distinct lines through P that do not intersect R.

This implies that there are through P an infinite number of coplanar lines that do not intersect R.

These non-intersecting lines are divided into two classes:

- Two of the lines (x and y in the diagram) are limiting parallels (sometimes called critically parallel, horoparallel or just parallel): there is one in the direction of each of the ideal points at the "ends" of R, asymptotically approaching R, always getting closer to R, but never meeting it.

- All other non-intersecting lines have a point of minimum distance and diverge from both sides of that point, and are called ultraparallel, diverging parallel or sometimes non-intersecting.

Some geometers simply use the phrase "parallel lines" to mean "limiting parallel lines", with ultraparallel lines meaning just non-intersecting.

These limiting parallels make an angle θ with PB; this angle depends only on the Gaussian curvature of the plane and the distance PB and is called the angle of parallelism.

For ultraparallel lines, the ultraparallel theorem states that there is a unique line in the hyperbolic plane that is perpendicular to each pair of ultraparallel lines.

Circles and disks

[edit]In hyperbolic geometry, the circumference of a circle of radius r is greater than .

Let , where is the Gaussian curvature of the plane. In hyperbolic geometry, is negative, so the square root is of a positive number.

Then the circumference of a circle of radius r is equal to:

And the area of the enclosed disk is:

Therefore, in hyperbolic geometry the ratio of a circle's circumference to its radius is always strictly greater than , though it can be made arbitrarily close by selecting a small enough circle.

If the Gaussian curvature of the plane is −1 then the geodesic curvature of a circle of radius r is: [1]

Hypercycles and horocycles

[edit]

In hyperbolic geometry, there is no line whose points are all equidistant from another line. Instead, the points that are all the same distance from a given line lie on a curve called a hypercycle.

Another special curve is the horocycle, whose normal radii (perpendicular lines) are all limiting parallel to each other (all converge asymptotically in one direction to the same ideal point, the centre of the horocycle).

Through every pair of points there are two horocycles. The centres of the horocycles are the ideal points of the perpendicular bisector of the line-segment between them.

Given any three distinct points, they all lie on either a line, hypercycle, horocycle, or circle.

The length of a line-segment is the shortest length between two points.

The arc-length of a hypercycle connecting two points is longer than that of the line segment and shorter than that of the arc horocycle, connecting the same two points.

The lengths of the arcs of both horocycles connecting two points are equal, and are longer than the arclength of any hypercycle connecting the points and shorter than the arc of any circle connecting the two points.

If the Gaussian curvature of the plane is −1, then the geodesic curvature of a horocycle is 1 and that of a hypercycle is between 0 and 1.[1]

Triangles

[edit]Unlike Euclidean triangles, where the angles always add up to π radians (180°, a straight angle), in hyperbolic space the sum of the angles of a triangle is always strictly less than π radians (180°). The difference is called the defect. Generally, the defect of a convex hyperbolic polygon with sides is its angle sum subtracted from .

The area of a hyperbolic triangle is given by its defect in radians multiplied by R2, which is also true for all convex hyperbolic polygons.[2] Therefore, all hyperbolic triangles have an area less than or equal to R2π. The area of a hyperbolic ideal triangle in which all three angles are 0° is equal to this maximum.

As in Euclidean geometry, each hyperbolic triangle has an incircle. In hyperbolic space, if all three of its vertices lie on a horocycle or hypercycle, then the triangle has no circumscribed circle.

As in spherical and elliptical geometry, in hyperbolic geometry if two triangles are similar, they must be congruent.

Regular apeirogon and pseudogon

[edit]

Special polygons in hyperbolic geometry are the regular apeirogon and pseudogon uniform polygons with an infinite number of sides.

In Euclidean geometry, the only way to construct such a polygon is to make the side lengths tend to zero and the apeirogon is indistinguishable from a circle, or make the interior angles tend to 180° and the apeirogon approaches a straight line.

However, in hyperbolic geometry, a regular apeirogon or pseudogon has sides of any length (i.e., it remains a polygon with noticeable sides).

The side and angle bisectors will, depending on the side length and the angle between the sides, be limiting or diverging parallel. If the bisectors are limiting parallel then it is an apeirogon and can be inscribed and circumscribed by concentric horocycles.

If the bisectors are diverging parallel then it is a pseudogon and can be inscribed and circumscribed by hypercycles (since all its vertices are the same distance from a line, the axis, and the midpoints of its sides are also equidistant from that same axis).

Tessellations

[edit]

Like the Euclidean plane it is also possible to tessellate the hyperbolic plane with regular polygons as faces.

There are an infinite number of uniform tilings based on the Schwarz triangles (p q r) where 1/p + 1/q + 1/r < 1, where p, q, r are each orders of reflection symmetry at three points of the fundamental domain triangle, the symmetry group is a hyperbolic triangle group. There are also infinitely many uniform tilings that cannot be generated from Schwarz triangles, some for example requiring quadrilaterals as fundamental domains.[3]

Standardized Gaussian curvature

[edit]Though hyperbolic geometry applies for any surface with a constant negative Gaussian curvature, it is usual to assume a scale in which the curvature K is −1.

This results in some formulas becoming simpler. Some examples are:

- The area of a triangle is equal to its angle defect in radians.

- The area of a horocyclic sector is equal to the length of its horocyclic arc.

- An arc of a horocycle so that a line that is tangent at one endpoint is limiting parallel to the radius through the other endpoint has a length of 1.[4]

- The ratio of the arc lengths between two radii of two concentric horocycles where the horocycles are a distance 1 apart is e : 1.[4]

Cartesian-like coordinate systems

[edit]Compared to Euclidean geometry, hyperbolic geometry presents many difficulties for a coordinate system: the angle sum of a quadrilateral is always less than 360°; there are no equidistant lines, so a proper rectangle would need to be enclosed by two lines and two hypercycles; parallel-transporting a line segment around a quadrilateral causes it to rotate when it returns to the origin; etc.

There are however different coordinate systems for hyperbolic plane geometry. All are based around choosing a point (the origin) on a chosen directed line (the x-axis) and after that many choices exist.

The Lobachevsky coordinates x and y are found by dropping a perpendicular onto the x-axis. x will be the label of the foot of the perpendicular. y will be the distance along the perpendicular of the given point from its foot (positive on one side and negative on the other).

Another coordinate system measures the distance from the point to the horocycle through the origin centered around and the length along this horocycle.[5]

Other coordinate systems use the Klein model or the Poincaré disk model described below, and take the Euclidean coordinates as hyperbolic.

Distance

[edit]A Cartesian-like[citation needed] coordinate system (x, y) on the oriented hyperbolic plane is constructed as follows. Choose a line in the hyperbolic plane together with an orientation and an origin o on this line. Then:

- the x-coordinate of a point is the signed distance of its projection onto the line (the foot of the perpendicular segment to the line from that point) to the origin;

- the y-coordinate is the signed distance from the point to the line, with the sign according to whether the point is on the positive or negative side of the oriented line.

The distance between two points represented by (x_i, y_i), i=1,2 in this coordinate system is[citation needed]

This formula can be derived from the formulas about hyperbolic triangles.

The corresponding metric tensor field is: .

In this coordinate system, straight lines take one of these forms ((x, y) is a point on the line; x0, y0, A, and α are parameters):

ultraparallel to the x-axis

asymptotically parallel on the negative side

asymptotically parallel on the positive side

intersecting perpendicularly

intersecting at an angle α

Generally, these equations will only hold in a bounded domain (of x values). At the edge of that domain, the value of y blows up to ±infinity.

History

[edit]Since the publication of Euclid's Elements around 300 BC, many geometers tried to prove the parallel postulate. Some tried to prove it by assuming its negation and trying to derive a contradiction. Foremost among these were Proclus, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen), Omar Khayyám,[6] Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī, Witelo, Gersonides, Alfonso, and later Giovanni Gerolamo Saccheri, John Wallis, Johann Heinrich Lambert, and Legendre.[7] Their attempts were doomed to failure (as we now know, the parallel postulate is not provable from the other postulates), but their efforts led to the discovery of hyperbolic geometry.

The theorems of Alhacen, Khayyam and al-Tūsī on quadrilaterals, including the Ibn al-Haytham–Lambert quadrilateral and Khayyam–Saccheri quadrilateral, were the first theorems on hyperbolic geometry. Their works on hyperbolic geometry had a considerable influence on its development among later European geometers, including Witelo, Gersonides, Alfonso, John Wallis and Saccheri.[8]

In the 18th century, Johann Heinrich Lambert introduced the hyperbolic functions[9] and computed the area of a hyperbolic triangle.[10]

19th-century developments

[edit]In the 19th century, hyperbolic geometry was explored extensively by Nikolai Lobachevsky, János Bolyai, Carl Friedrich Gauss and Franz Taurinus. Unlike their predecessors, who just wanted to eliminate the parallel postulate from the axioms of Euclidean geometry, these authors realized they had discovered a new geometry.[11][12]

Gauss wrote in an 1824 letter to Franz Taurinus that he had constructed it, but Gauss did not publish his work. Gauss called it "non-Euclidean geometry"[13] causing several modern authors to continue to consider "non-Euclidean geometry" and "hyperbolic geometry" to be synonyms. Taurinus published results on hyperbolic trigonometry in 1826, argued that hyperbolic geometry is self-consistent, but still believed in the special role of Euclidean geometry. The complete system of hyperbolic geometry was published by Lobachevsky in 1829/1830, while Bolyai discovered it independently and published in 1832.

In 1868, Eugenio Beltrami provided models of hyperbolic geometry, and used this to prove that hyperbolic geometry was consistent if and only if Euclidean geometry was.

The term "hyperbolic geometry" was introduced by Felix Klein in 1871.[14] Klein followed an initiative of Arthur Cayley to use the transformations of projective geometry to produce isometries. The idea used a conic section or quadric to define a region, and used cross ratio to define a metric. The projective transformations that leave the conic section or quadric stable are the isometries. "Klein showed that if the Cayley absolute is a real curve then the part of the projective plane in its interior is isometric to the hyperbolic plane..."[15]

Philosophical consequences

[edit]The discovery of hyperbolic geometry had important philosophical consequences. Before its discovery many philosophers (such as Hobbes and Spinoza) viewed philosophical rigor in terms of the "geometrical method", referring to the method of reasoning used in Euclid's Elements.

Kant in Critique of Pure Reason concluded that space (in Euclidean geometry) and time are not discovered by humans as objective features of the world, but are part of an unavoidable systematic framework for organizing our experiences.[16]

It is said that Gauss did not publish anything about hyperbolic geometry out of fear of the "uproar of the Boeotians" (stereotyped as dullards by the ancient Athenians[17]), which would ruin his status as princeps mathematicorum (Latin, "the Prince of Mathematicians").[18] The "uproar of the Boeotians" came and went, and gave an impetus to great improvements in mathematical rigour, analytical philosophy and logic. Hyperbolic geometry was finally proved consistent and is therefore another valid geometry.

Geometry of the universe (spatial dimensions only)

[edit]Because Euclidean, hyperbolic and elliptic geometry are all consistent, the question arises: which is the real geometry of space, and if it is hyperbolic or elliptic, what is its curvature?

Lobachevsky had already tried to measure the curvature of the universe by measuring the parallax of Sirius and treating Sirius as the ideal point of an angle of parallelism. He realized that his measurements were not precise enough to give a definite answer, but he did reach the conclusion that if the geometry of the universe is hyperbolic, then the absolute length is at least one million times the diameter of Earth's orbit (2000000 AU, 10 parsec).[19] Some argue that his measurements were methodologically flawed.[20]

Henri Poincaré, with his sphere-world thought experiment, came to the conclusion that everyday experience does not necessarily rule out other geometries.

The geometrization conjecture gives a complete list of eight possibilities for the fundamental geometry of our space. The problem in determining which one applies is that, to reach a definitive answer, we need to be able to look at extremely large shapes – much larger than anything on Earth or perhaps even in our galaxy.[21]

Geometry of the universe (special relativity)

[edit]Special relativity places space and time on equal footing, so that one considers the geometry of a unified spacetime instead of considering space and time separately.[22][23] Minkowski geometry replaces Galilean geometry (which is the 3-dimensional Euclidean space with time of Galilean relativity).[24]

In relativity, rather than Euclidean, elliptic and hyperbolic geometry, the appropriate geometries to consider are Minkowski space, de Sitter space and anti-de Sitter space,[25][26] corresponding to zero, positive and negative curvature respectively.

Hyperbolic geometry enters special relativity through rapidity, which stands in for velocity, and is expressed by a hyperbolic angle. The study of this velocity geometry has been called kinematic geometry. The space of relativistic velocities has a three-dimensional hyperbolic geometry, where the distance function is determined from the relative velocities of "nearby" points (velocities).[27]

Physical realizations of the hyperbolic plane

[edit]

There exist various pseudospheres in Euclidean space that have a finite area of constant negative Gaussian curvature.

By Hilbert's theorem, one cannot isometrically immerse a complete hyperbolic plane (a complete regular surface of constant negative Gaussian curvature) in a 3-D Euclidean space.

Other useful models of hyperbolic geometry exist in Euclidean space, in which the metric is not preserved. A particularly well-known paper model based on the pseudosphere is due to William Thurston.

The art of crochet has been used to demonstrate hyperbolic planes, the first such demonstration having been made by Daina Taimiņa.[28]

In 2000, Keith Henderson demonstrated a quick-to-make paper model dubbed the "hyperbolic soccerball" (more precisely, a truncated order-7 triangular tiling).[29][30]

Instructions on how to make a hyperbolic quilt, designed by Helaman Ferguson,[31] have been made available by Jeff Weeks.[32]

Models of the hyperbolic plane

[edit]Various pseudospheres – surfaces with constant negative Gaussian curvature – can be embedded in 3-D space under the standard Euclidean metric, and so can be made into tangible models. Of these, the tractoid (or pseudosphere) is the best known; using the tractoid as a model of the hyperbolic plane is analogous to using a cone or cylinder as a model of the Euclidean plane. However, the entire hyperbolic plane cannot be embedded into Euclidean space in this way, and various other models are more convenient for abstractly exploring hyperbolic geometry.

There are four models commonly used for hyperbolic geometry: the Klein model, the Poincaré disk model, the Poincaré half-plane model, and the Lorentz or hyperboloid model. These models define a hyperbolic plane which satisfies the axioms of a hyperbolic geometry. Despite their names, the first three mentioned above were introduced as models of hyperbolic space by Beltrami, not by Poincaré or Klein. All these models are extendable to more dimensions.

The Beltrami–Klein model

[edit]The Beltrami–Klein model, also known as the projective disk model, Klein disk model and Klein model, is named after Eugenio Beltrami and Felix Klein.

For the two dimensions this model uses the interior of the unit circle for the complete hyperbolic plane, and the chords of this circle are the hyperbolic lines.

For higher dimensions this model uses the interior of the unit ball, and the chords of this n-ball are the hyperbolic lines.

- This model has the advantage that lines are straight, but the disadvantage that angles are distorted (the mapping is not conformal), and also circles are not represented as circles.

- The distance in this model is half the logarithm of the cross-ratio, which was introduced by Arthur Cayley in projective geometry.

The Poincaré disk model

[edit]

The Poincaré disk model, also known as the conformal disk model, also employs the interior of the unit circle, but lines are represented by arcs of circles that are orthogonal to the boundary circle, plus diameters of the boundary circle.

- This model preserves angles, and is thereby conformal. All isometries within this model are therefore Möbius transformations.

- Circles entirely within the disk remain circles although the Euclidean center of the circle is closer to the center of the disk than is the hyperbolic center of the circle.

- Horocycles are circles within the disk which are tangent to the boundary circle, minus the point of contact.

- Hypercycles are open-ended chords and circular arcs within the disc that terminate on the boundary circle at non-orthogonal angles.

The Poincaré half-plane model

[edit]The Poincaré half-plane model takes one-half of the Euclidean plane, bounded by a line B of the plane, to be a model of the hyperbolic plane. The line B is not included in the model.

The Euclidean plane may be taken to be a plane with the Cartesian coordinate system and the x-axis is taken as line B and the half plane is the upper half (y > 0 ) of this plane.

- Hyperbolic lines are then either half-circles orthogonal to B or rays perpendicular to B.

- The length of an interval on a ray is given by logarithmic measure so it is invariant under a homothetic transformation

- Like the Poincaré disk model, this model preserves angles, and is thus conformal. All isometries within this model are therefore Möbius transformations of the plane.

- The half-plane model is the limit of the Poincaré disk model whose boundary is tangent to B at the same point while the radius of the disk model goes to infinity.

The hyperboloid model

[edit]The hyperboloid model or Lorentz model employs a 2-dimensional hyperboloid of revolution (of two sheets, but using one) embedded in 3-dimensional Minkowski space. This model is generally credited to Poincaré, but Reynolds[33] says that Wilhelm Killing used this model in 1885

- This model has direct application to special relativity, as Minkowski 3-space is a model for spacetime, suppressing one spatial dimension. One can take the hyperboloid to represent the events (positions in spacetime) that various inertially moving observers, starting from a common event, will reach in a fixed proper time.

- The hyperbolic distance between two points on the hyperboloid can then be identified with the relative rapidity between the two corresponding observers.

- The model generalizes directly to an additional dimension: a hyperbolic 3-space three-dimensional hyperbolic geometry relates to Minkowski 4-space.

The hemisphere model

[edit]The hemisphere model is not often used as model by itself, but it functions as a useful tool for visualizing transformations between the other models.

The hemisphere model uses the upper half of the unit sphere:

The hyperbolic lines are half-circles orthogonal to the boundary of the hemisphere.

The hemisphere model is part of a Riemann sphere, and different projections give different models of the hyperbolic plane:

- Stereographic projection from onto the plane projects corresponding points on the Poincaré disk model

- Stereographic projection from onto the surface projects corresponding points on the hyperboloid model

- Stereographic projection from onto the plane projects corresponding points on the Poincaré half-plane model

- Orthographic projection onto a plane projects corresponding points on the Beltrami–Klein model.

- Central projection from the centre of the sphere onto the plane projects corresponding points on the Gans Model

Connection between the models

[edit]

All models essentially describe the same structure. The difference between them is that they represent different coordinate charts laid down on the same metric space, namely the hyperbolic plane. The characteristic feature of the hyperbolic plane itself is that it has a constant negative Gaussian curvature, which is indifferent to the coordinate chart used. The geodesics are similarly invariant: that is, geodesics map to geodesics under coordinate transformation. Hyperbolic geometry is generally introduced in terms of the geodesics and their intersections on the hyperbolic plane.[34]

Once we choose a coordinate chart (one of the "models"), we can always embed it in a Euclidean space of same dimension, but the embedding is clearly not isometric (since the curvature of Euclidean space is 0). The hyperbolic space can be represented by infinitely many different charts; but the embeddings in Euclidean space due to these four specific charts show some interesting characteristics.

Since the four models describe the same metric space, each can be transformed into the other.

See, for example:

- the Beltrami–Klein model's relation to the hyperboloid model,

- the Beltrami–Klein model's relation to the Poincaré disk model,

- and the Poincaré disk model's relation to the hyperboloid model.

Other models of hyperbolic geometry

[edit]The Gans model

[edit]In 1966 David Gans proposed a flattened hyperboloid model in the journal American Mathematical Monthly.[35] It is an orthographic projection of the hyperboloid model onto the xy-plane. This model is not as widely used as other models but nevertheless is quite useful in the understanding of hyperbolic geometry.

- Unlike the Klein or the Poincaré models, this model utilizes the entire Euclidean plane.

- The lines in this model are represented as branches of a hyperbola.[36]

The conformal square model

[edit]

The conformal square model of the hyperbolic plane arises from using Schwarz–Christoffel mapping to convert the Poincaré disk into a square.[37] This model has finite extent, like the Poincaré disk. However, all of the points are inside a square. This model is conformal, which makes it suitable for artistic applications.

The band model

[edit]The band model employs a portion of the Euclidean plane between two parallel lines.[38] Distance is preserved along one line through the middle of the band. Assuming the band is given by , the metric is given by .

Isometries of the hyperbolic plane

[edit]Every isometry (transformation or motion) of the hyperbolic plane to itself can be realized as the composition of at most three reflections. In n-dimensional hyperbolic space, up to n+1 reflections might be required. (These are also true for Euclidean and spherical geometries, but the classification below is different.)

All isometries of the hyperbolic plane can be classified into these classes:

- Orientation preserving

- the identity isometry – nothing moves; zero reflections; zero degrees of freedom.

- inversion through a point (half turn) – two reflections through mutually perpendicular lines passing through the given point, i.e. a rotation of 180 degrees around the point; two degrees of freedom.

- rotation around a normal point – two reflections through lines passing through the given point (includes inversion as a special case); points move on circles around the center; three degrees of freedom.

- "rotation" around an ideal point (horolation) – two reflections through lines leading to the ideal point; points move along horocycles centered on the ideal point; two degrees of freedom.

- translation along a straight line – two reflections through lines perpendicular to the given line; points off the given line move along hypercycles; three degrees of freedom.

- Orientation reversing

- reflection through a line – one reflection; two degrees of freedom.

- combined reflection through a line and translation along the same line – the reflection and translation commute; three reflections required; three degrees of freedom.[citation needed]

In art

[edit]M. C. Escher's famous prints Circle Limit III and Circle Limit IV illustrate the conformal disc model (Poincaré disk model) quite well. The white lines in III are not quite geodesics (they are hypercycles), but are close to them. It is also possible to see the negative curvature of the hyperbolic plane, through its effect on the sum of angles in triangles and squares.

For example, in Circle Limit III every vertex belongs to three triangles and three squares. In the Euclidean plane, their angles would sum to 450°; i.e., a circle and a quarter. From this, we see that the sum of angles of a triangle in the hyperbolic plane must be smaller than 180°. Another visible property is exponential growth. In Circle Limit III, for example, one can see that the number of fishes within a distance of n from the center rises exponentially. The fishes have an equal hyperbolic area, so the area of a ball of radius n must rise exponentially in n.

The art of crochet has been used to demonstrate hyperbolic planes (pictured above) with the first being made by Daina Taimiņa,[28] whose book Crocheting Adventures with Hyperbolic Planes won the 2009 Bookseller/Diagram Prize for Oddest Title of the Year.[39]

HyperRogue is a roguelike game set on various tilings of the hyperbolic plane.

Higher dimensions

[edit]Hyperbolic geometry is not limited to 2 dimensions; a hyperbolic geometry exists for every higher number of dimensions.

Homogeneous structure

[edit]Hyperbolic space of dimension n is a special case of a Riemannian symmetric space of noncompact type, as it is isomorphic to the quotient

The orthogonal group O(1, n) acts by norm-preserving transformations on Minkowski space R1,n, and it acts transitively on the two-sheet hyperboloid of norm 1 vectors. Timelike lines (i.e., those with positive-norm tangents) through the origin pass through antipodal points in the hyperboloid, so the space of such lines yields a model of hyperbolic n-space. The stabilizer of any particular line is isomorphic to the product of the orthogonal groups O(n) and O(1), where O(n) acts on the tangent space of a point in the hyperboloid, and O(1) reflects the line through the origin. Many of the elementary concepts in hyperbolic geometry can be described in linear algebraic terms: geodesic paths are described by intersections with planes through the origin, dihedral angles between hyperplanes can be described by inner products of normal vectors, and hyperbolic reflection groups can be given explicit matrix realizations.

In small dimensions, there are exceptional isomorphisms of Lie groups that yield additional ways to consider symmetries of hyperbolic spaces. For example, in dimension 2, the isomorphisms SO+(1, 2) ≅ PSL(2, R) ≅ PSU(1, 1) allow one to interpret the upper half plane model as the quotient SL(2, R)/SO(2) and the Poincaré disc model as the quotient SU(1, 1)/U(1). In both cases, the symmetry groups act by fractional linear transformations, since both groups are the orientation-preserving stabilizers in PGL(2, C) of the respective subspaces of the Riemann sphere. The Cayley transformation not only takes one model of the hyperbolic plane to the other, but realizes the isomorphism of symmetry groups as conjugation in a larger group. In dimension 3, the fractional linear action of PGL(2, C) on the Riemann sphere is identified with the action on the conformal boundary of hyperbolic 3-space induced by the isomorphism O+(1, 3) ≅ PGL(2, C). This allows one to study isometries of hyperbolic 3-space by considering spectral properties of representative complex matrices. For example, parabolic transformations are conjugate to rigid translations in the upper half-space model, and they are exactly those transformations that can be represented by unipotent upper triangular matrices.

See also

[edit]- Band model

- Constructions in hyperbolic geometry

- Hjelmslev transformation

- Hyperbolic 3-manifold

- Hyperbolic manifold

- Hyperbolic set

- Hyperbolic tree

- Kleinian group

- Lambert quadrilateral

- Open universe

- Poincaré metric

- Saccheri quadrilateral

- Systolic geometry

- Uniform tilings in hyperbolic plane

- δ-hyperbolic space

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Curvature of curves on the hyperbolic plane". math stackexchange. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ Thorgeirsson, Sverrir (2014). Hyperbolic geometry: history, models, and axioms.

- ^ Hyde, S.T.; Ramsden, S. (2003). "Some novel three-dimensional Euclidean crystalline networks derived from two-dimensional hyperbolic tilings". The European Physical Journal B. 31 (2): 273–284. Bibcode:2003EPJB...31..273H. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.720.5527. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2003-00032-8. S2CID 41146796.

- ^ a b Sommerville, D.M.Y. (2005). The elements of non-Euclidean geometry (Unabr. and unaltered republ. ed.). Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. p. 58. ISBN 0-486-44222-5.

- ^ Ramsay, Arlan; Richtmyer, Robert D. (1995). Introduction to hyperbolic geometry. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 97–103. ISBN 0387943390.

- ^ See for instance, "Omar Khayyam 1048–1131". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ^ "Non-Euclidean Geometry Seminar". Math.columbia.edu. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ Boris A. Rosenfeld and Adolf P. Youschkevitch (1996), "Geometry", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, Vol. 2, p. 447–494 [470], Routledge, London and New York:

"Three scientists, Ibn al-Haytham, Khayyam and al-Tūsī, had made the most considerable contribution to this branch of geometry whose importance came to be completely recognized only in the 19th century. In essence their propositions concerning the properties of quadrangles which they considered assuming that some of the angles of these figures were acute of obtuse, embodied the first few theorems of the hyperbolic and the elliptic geometries. Their other proposals showed that various geometric statements were equivalent to the Euclidean postulate V. It is extremely important that these scholars established the mutual connection between this postulate and the sum of the angles of a triangle and a quadrangle. By their works on the theory of parallel lines Arab mathematicians directly influenced the relevant investigations of their European counterparts. The first European attempt to prove the postulate on parallel lines – made by Witelo, the Polish scientists of the 13th century, while revising Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics (Kitab al-Manazir) – was undoubtedly prompted by Arabic sources. The proofs put forward in the 14th century by the Jewish scholar Levi ben Gerson, who lived in southern France, and by the above-mentioned Alfonso from Spain directly border on Ibn al-Haytham's demonstration. Above, we have demonstrated that Pseudo-Tusi's Exposition of Euclid had stimulated both J. Wallis's and G. Saccheri's studies of the theory of parallel lines."

- ^ Eves, Howard (2012), Foundations and Fundamental Concepts of Mathematics, Courier Dover Publications, p. 59, ISBN 9780486132204,

We also owe to Lambert the first systematic development of the theory of hyperbolic functions and, indeed, our present notation for these functions.

- ^ Ratcliffe, John (2006), Foundations of Hyperbolic Manifolds, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 149, Springer, p. 99, ISBN 9780387331973,

That the area of a hyperbolic triangle is proportional to its angle defect first appeared in Lambert's monograph Theorie der Parallellinien, which was published posthumously in 1786.

- ^ Bonola, R. (1912). Non-Euclidean geometry: A critical and historical study of its development. Chicago: Open Court.

- ^ Greenberg, Marvin Jay (2003). Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries: development and history (3rd ed.). New York: Freeman. p. 177. ISBN 0716724464.

Out of nothing I have created a strange new universe. JÁNOS BOLYAI

- ^ Felix Klein, Elementary Mathematics from an Advanced Standpoint: Geometry, Dover, 1948 (reprint of English translation of 3rd Edition, 1940. First edition in German, 1908) pg. 176

- ^ F. Klein. "Über die sogenannte Nicht-Euklidische Geometrie". Math. Ann. 4, 573–625 (also in Gesammelte Mathematische Abhandlungen 1, 244–350).

- ^ Rosenfeld, B.A. (1988) A History of Non-Euclidean Geometry, page 236, Springer-Verlag ISBN 0-387-96458-4

- ^ Lucas, John Randolph (1984). Space, Time and Causality. Clarendon Press. p. 149. ISBN 0-19-875057-9.

- ^ Wood, Donald (April 1959). "Some Greek stereotypes of other peoples". Race. 1 (2): 65–71. doi:10.1177/030639685900100207.

- ^ Torretti, Roberto (1978). Philosophy of Geometry from Riemann to Poincare. Dordrecht Holland: Reidel. p. 255.

- ^ Bonola, Roberto (1955). Non-Euclidean geometry : a critical and historical study of its developments (Unabridged and unaltered republ. of the 1. English translation 1912. ed.). New York, NY: Dover. p. 95. ISBN 0486600270.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Richtmyer, Arlan Ramsay, Robert D. (1995). Introduction to hyperbolic geometry. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 118–120. ISBN 0387943390.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mathematics Illuminated - Unit 8 - 8.8 Geometrization Conjecture". Learner.org. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ L. D. Landau; E. M. Lifshitz (1973). Classical Theory of Fields. Course of Theoretical Physics. Vol. 2 (4th ed.). Butterworth Heinemann. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-0-7506-2768-9.

- ^ R. P. Feynman; R. B. Leighton; M. Sands (1963). Feynman Lectures on Physics. Vol. 1. Addison Wesley. p. (17-1)–(17-3). ISBN 0-201-02116-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ J. R. Forshaw; A. G. Smith (2008). Dynamics and Relativity. Manchester physics series. Wiley. pp. 246–248. ISBN 978-0-470-01460-8.

- ^ Misner; Thorne; Wheeler (1973). Gravitation. pp. 21, 758.

- ^ John K. Beem; Paul Ehrlich; Kevin Easley (1996). Global Lorentzian Geometry (Second ed.).

- ^ L. D. Landau; E. M. Lifshitz (1973). Classical Theory of Fields. Course of Theoretical Physics. Vol. 2 (4th ed.). Butterworth Heinemann. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7506-2768-9.

- ^ a b "Hyperbolic Space". The Institute for Figuring. December 21, 2006. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- ^ "How to Build your own Hyperbolic Soccer Ball" (PDF). Theiff.org. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "Hyperbolic Football". Math.tamu.edu. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "Helaman Ferguson, Hyperbolic Quilt". Archived from the original on 2011-07-11.

- ^ "How to sew a Hyperbolic Blanket". Geometrygames.org. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ Reynolds, William F., (1993) Hyperbolic Geometry on a Hyperboloid, American Mathematical Monthly 100:442–455.

- ^ Arlan Ramsay, Robert D. Richtmyer, Introduction to Hyperbolic Geometry, Springer; 1 edition (December 16, 1995)

- ^ Gans David (March 1966). "A New Model of the Hyperbolic Plane". American Mathematical Monthly. 73 (3): 291–295. doi:10.2307/2315350. JSTOR 2315350.

- ^ vcoit (8 May 2015). "Computer Science Department" (PDF).

- ^ Fong, C. (2016). The Conformal Hyperbolic Square and Its Ilk (PDF). Bridges Finland Conference Proceedings.

- ^ "2" (PDF). Teichmüller theory and applications to geometry, topology, and dynamics. Hubbard, John Hamal. Ithaca, NY: Matrix Editions. 2006–2016. p. 25. ISBN 9780971576629. OCLC 57965863.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bloxham, Andy (March 26, 2010). "Crocheting Adventures with Hyperbolic Planes wins oddest book title award". The Telegraph.

Bibliography

[edit]- A'Campo, Norbert and Papadopoulos, Athanase, (2012) Notes on hyperbolic geometry, in: Strasbourg Master class on Geometry, pp. 1–182, IRMA Lectures in Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, Vol. 18, Zürich: European Mathematical Society (EMS), 461 pages, SBN ISBN 978-3-03719-105-7, DOI 10.4171–105.

- Coxeter, H. S. M., (1942) Non-Euclidean geometry, University of Toronto Press, Toronto

- Fenchel, Werner (1989). Elementary geometry in hyperbolic space. De Gruyter Studies in mathematics. Vol. 11. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter & Co.

- Fenchel, Werner; Nielsen, Jakob (2003). Asmus L. Schmidt (ed.). Discontinuous groups of isometries in the hyperbolic plane. De Gruyter Studies in mathematics. Vol. 29. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co.

- Lobachevsky, Nikolai I., (2010) Pangeometry, Edited and translated by Athanase Papadopoulos, Heritage of European Mathematics, Vol. 4. Zürich: European Mathematical Society (EMS). xii, 310~p, ISBN 978-3-03719-087-6/hbk

- Milnor, John W., (1982) Hyperbolic geometry: The first 150 years, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) Volume 6, Number 1, pp. 9–24.

- Reynolds, William F., (1993) Hyperbolic Geometry on a Hyperboloid, American Mathematical Monthly 100:442–455.

- Stillwell, John (1996). Sources of hyperbolic geometry. History of Mathematics. Vol. 10. Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-0529-9. MR 1402697.

- Samuels, David, (March 2006) Knit Theory Discover Magazine, volume 27, Number 3.

- James W. Anderson, Hyperbolic Geometry, Springer 2005, ISBN 1-85233-934-9

- James W. Cannon, William J. Floyd, Richard Kenyon, and Walter R. Parry (1997) Hyperbolic Geometry, MSRI Publications, volume 31.

External links

[edit]- Javascript freeware for creating sketches in the Poincaré Disk Model of Hyperbolic Geometry University of New Mexico

- "The Hyperbolic Geometry Song" A short music video about the basics of Hyperbolic Geometry available at YouTube.

- "Lobachevskii geometry", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Gauss–Bolyai–Lobachevsky Space". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Hyperbolic Geometry". MathWorld.

- More on hyperbolic geometry, including movies and equations for conversion between the different models University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Hyperbolic Voronoi diagrams made easy, Frank Nielsen

- Stothers, Wilson (2000). "Hyperbolic geometry". maths.gla.ac.uk. University of Glasgow., interactive instructional website.

- Hyperbolic Planar Tesselations

- Models of the Hyperbolic Plane

Hyperbolic geometry

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Relation to Euclidean Geometry

Hyperbolic geometry emerges as a non-Euclidean geometry by replacing Euclid's parallel postulate, which states that through a point not on a given line, exactly one line can be drawn parallel to the given line; in hyperbolic geometry, at least two such parallel lines exist. This alteration fundamentally distinguishes it from Euclidean geometry, where the parallel postulate ensures unique parallelism and underpins much of classical plane geometry. The failure of this postulate allows for geometries with intrinsic properties that deviate sharply from everyday spatial intuitions derived from Euclidean principles.[10] A pivotal difference lies in the properties of triangles: in Euclidean geometry, the sum of the interior angles of any triangle measures exactly 180 degrees, whereas in hyperbolic geometry, this sum is always less than 180 degrees, with the deficit proportional to the triangle's area. This angle defect arises directly from the modified parallel postulate and highlights how hyperbolic space "expands" more rapidly than Euclidean space. Among non-Euclidean geometries, hyperbolic geometry is characterized by constant negative Gaussian curvature, contrasting with elliptic geometry's constant positive curvature, as seen in spherical surfaces; Euclidean geometry, by comparison, has zero curvature.[11][12][13] Basic consequences of this framework include the exponential growth of area with radius in hyperbolic space—for instance, the area of a disk increases exponentially rather than quadratically as in Euclidean geometry—leading to phenomena like infinitely many tessellations and divergent parallels that underscore the geometry's expansive nature. This contrasts with the linear or polynomial growth in Euclidean settings and has profound implications for understanding curved spaces in mathematics and physics.[14]Axioms and Postulates

Hyperbolic geometry is founded on a set of axioms that diverge from Euclidean geometry primarily in the treatment of parallelism, while retaining much of the foundational structure. Euclid's original five postulates provide the starting point for this axiomatic system. The first postulate states that a straight line segment can be drawn joining any two points. The second asserts that any straight line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line. The third allows for the construction of a circle with any center and radius. The fourth declares that all right angles are equal to one another. These initial four postulates form the core of neutral or absolute geometry, which is consistent across both Euclidean and hyperbolic frameworks.[15] The fifth postulate, known as the parallel postulate, marks the key distinction. In Euclidean geometry, it states that if two lines are drawn that intersect a third line such that the sum of the interior angles on one side is less than two right angles, then the two lines must intersect if extended on that side; equivalently, through a point not on a given line, exactly one parallel line can be drawn. In hyperbolic geometry, this is replaced by the hyperbolic parallel postulate: through a point not on a given line, there are at least two lines parallel to the given line, and in fact infinitely many such parallels exist. This modification ensures that hyperbolic geometry satisfies the first four postulates but negates the Euclidean fifth.[5] Absolute geometry encompasses the theorems derivable from Euclid's first four postulates alone, without assuming the parallel postulate or its negation; it serves as the common foundation for both Euclidean and hyperbolic geometries, proving results like the existence of congruent triangles under SAS but leaving properties of parallels undetermined. To provide a more rigorous foundation, David Hilbert formalized a set of 20 axioms in 1899, grouped into incidence (defining points and lines), order (betweenness), congruence (equality of segments and angles), parallelism, and continuity. For hyperbolic geometry, Hilbert's system is adapted by replacing the Euclidean parallelism axiom (equivalent to Playfair's axiom, stating a unique parallel through a point not on a line) with the hyperbolic parallelism axiom: for any line and point not on it, there are two classes of lines through the point—those intersecting the given line (secants) and those not (parallels)—with infinitely many parallels in the non-intersecting class, and additionally, limiting parallels that approach the line asymptotically without intersecting. The incidence, order, congruence, and continuity axioms remain unchanged.[3] The logical independence of the parallel postulate from the other axioms was established in the 19th century through the construction of non-Euclidean models. Eugenio Beltrami in 1868 demonstrated that hyperbolic geometry is consistent relative to Euclidean geometry by constructing a projective model of the hyperbolic plane within a Euclidean disk (now known as the Beltrami–Klein model). Subsequent models, such as the Poincaré disk, further confirmed this independence by satisfying the first four postulates while violating the fifth. The hyperbolic parallel postulate is logically equivalent to several alternative formulations within absolute geometry. One such equivalence is the angle sum deficit: in hyperbolic geometry, the sum of the interior angles of any triangle is strictly less than 180 degrees, with the deficit proportional to the triangle's area. Another equivalence involves Saccheri quadrilaterals, which are defined by a base with two equal perpendicular sides of equal length; in hyperbolic geometry, the summit angles (opposite the base) are acute and equal, and the summit is longer than the base, contrasting with the Euclidean case where summit angles are right. These properties, explored by Giovanni Saccheri in 1733, demonstrate that assuming the hyperbolic postulate leads to acute summit angles and angle sums below 180 degrees, establishing the equivalences without reliance on specific models.[16][17]Geometric Elements

Lines and Parallels

In hyperbolic geometry, lines are defined as geodesics, which are the locally shortest paths between any two points in the space, analogous to straight lines in Euclidean geometry.[18] These geodesics satisfy the property that any segment of a geodesic lies on a unique geodesic connecting its endpoints, ensuring they serve as the fundamental "straight" elements for constructing figures and measuring distances.[19] Pairs of hyperbolic lines exhibit three distinct behaviors depending on their relative positions: they may intersect at a single point within the plane, approach each other asymptotically without intersecting (known as asymptotic or limiting parallels), or diverge without intersecting or approaching at infinity (termed ultraparallels). Intersecting lines cross at exactly one finite point, while asymptotic parallels share a common ideal point on the boundary at infinity, where they converge in direction but never meet in the finite plane. Ultraparallels, in contrast, maintain a positive minimum distance and possess a unique common perpendicular segment connecting them.[20] The boundary at infinity comprises all ideal points, which represent directions of unbounded geodesics and allow asymptotic parallels to be conceptualized as meeting "at infinity."[14] Given a hyperbolic line and a point not on , there exist infinitely many lines through that do not intersect : precisely two asymptotic parallels (one on each side of the perpendicular from to ) and infinitely many ultraparallels beyond them. These asymptotic parallels bound the family of non-intersecting lines, as any line through forming an angle smaller than that of the asymptotic parallel with the perpendicular will intersect , while larger angles yield ultraparallels.[21] The angle between the perpendicular from to and either asymptotic parallel through is called the angle of parallelism, denoted , where is the hyperbolic distance from to . For a space with Gaussian curvature , this angle is given by This function decreases from as to 0 as , reflecting how the "room" for parallels expands with distance.[22]Circles, Disks, Hypercycles, and Horocycles

In hyperbolic geometry, a circle is defined as the locus of all points at a fixed hyperbolic distance from a given center point. This contrasts with Euclidean circles, where the circumference grows linearly with the radius; in the hyperbolic case, it grows exponentially due to the negative curvature. For a hyperbolic plane with Gaussian curvature , the circumference of such a circle is given by[14][23] This formula approaches the Euclidean as (corresponding to ).[23] The area enclosed by the circle, forming a hyperbolic disk, is

[14][23] Like the circumference, this area expands exponentially with , allowing disks to cover increasingly large portions of the plane as the radius increases. A hyperbolic disk is the bounded region interior to a circle, with horodisks representing special limiting cases where the center lies at a point at infinity, making the disk tangent to the ideal boundary of the hyperbolic plane.[24] Hypercycles, or equidistant curves, are the sets of points maintaining a constant perpendicular hyperbolic distance from a given geodesic line; unlike geodesics, they are curved and do not represent shortest paths.[25] These curves generalize the notion of parallel lines but bend away from the reference geodesic, reflecting the space's diverging structure. Horocycles emerge as the limiting form of hypercycles when the fixed distance approaches infinity, effectively positioning the "center" at an ideal point on the boundary at infinity.[25] They can be regarded as circles of infinite radius tangent to the ideal boundary and play a role analogous to straight lines in certain transformations of the space. Horocycles exhibit Euclidean-like geometry locally along their length, where arc length measurements behave linearly as in a flat line. A key property of the family of circles, horocycles, and hypercycles is that any three non-collinear points lie on exactly one such curve, which is a circle if the perpendicular bisectors of the triangle they form intersect at a finite point, a horocycle if the bisectors are asymptotic, or a hypercycle if the bisectors are ultraparallel.[26]