Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Polysomy

View on Wikipedia

Polysomy is a condition found in many species, including fungi, plants, insects, and mammals, in which an organism has at least one more chromosome than normal, i.e., there may be three or more copies of the chromosome rather than the expected two copies.[1] Most eukaryotic species are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, whereas prokaryotes are haploid, containing a single chromosome in each cell. Aneuploids possess chromosome numbers that are not exact multiples of the haploid number and polysomy is a type of aneuploidy.[2] A karyotype is the set of chromosomes in an organism and the suffix -somy is used to name aneuploid karyotypes. This is not to be confused with the suffix -ploidy, referring to the number of complete sets of chromosomes.

Polysomy is usually caused by non-disjunction (the failure of a pair of homologous chromosomes to separate) during meiosis, but may also be due to a translocation mutation (a chromosome abnormality caused by rearrangement of parts between nonhomologous chromosomes). Polysomy is found in many diseases, including Down syndrome in humans where affected individuals possess three copies (trisomy) of chromosome 21.[3]

Polysomic inheritance occurs during meiosis when chiasmata form between more than two homologous partners, producing multivalent chromosomes.[1] Autopolyploids may show polysomic inheritance of all the linkage groups, and their fertility may be reduced due to unbalanced chromosome numbers in the gametes.[1] In tetrasomic inheritance, four copies of a linkage group rather than two (tetrasomy) assort two-by-two.[1]

Types

[edit]Polysomy types are categorized based on the number of extra chromosomes in each set, noted as a diploid (2n) with an extra chromosome of various numbers. For example, a polysomy with three chromosomes is called a trisomy, a polysomy with four chromosomes is called tetrasomy, etc.:[4]

| Number of chromosomes | Name | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | trisomy | Three copies of a chromosome, 2n + 1 | Down syndrome (Trisomy 21), Edwards syndrome (Trisomy 18), or Patau syndrome (Trisomy 13)[3] |

| 4 | tetrasomy | Four copies of a chromosome, 2n + 2 | Tetrasomy 9p, Tetrasomy 18p[5] |

| 5 | pentasomy | Five copies of a chromosome, 2n + 3 | Pentasomy X (XXXXX or 49, XXXXX)[6] |

| 6 | hexasomy | Six copies of a chromosome, 2n + 4 | Mosaic hexasomy 21 or partial hexasomy 15[7] |

| 7 | heptasomy | Seven copies of a chromosome, 2n + 5 | Heptasomy 21 in acute myeloid leukemia[8] |

| 8 | octosomy | Eight copies of a chromosome, 2n + 6 | Octosomy in sturgeon fish (Acipenser baerii, A. persicus, A. sinensis, and A. transmontanus)[9] |

| 9 | nonasomy | Nine copies of a chromosome, 2n + 7 | Nonasomy in congenital skeletal polydystrophy[10] |

| 10 | decasomy | Ten copies of a chromosome, 2n + 8 | decasomy 8 in histolytic carcinoma[11] |

In mammals

[edit]In canines

[edit]

Polysomy plays a role in canine leukemia, hemangiopericytomas, and thyroid tumors.[12] Abnormalities of chromosome 13 have been observed in canine osteoid chondrosarcoma and lymphosarcoma.[13] Trisomy 13 in dogs with lymphosarcoma show a longer duration of first remission (medicine) and survival, responding well to treatments with chemotherapeutic agents.[14] Polysomy of chromosome 13 (Polysomy 13) is significant in the development of prostate cancer and is often caused by centric fusions.[12] Since canine chromosome 13 is similar to human chromosome 8q, research could provide insight to treatment for prostate cancer in humans.[15] Polysomy of chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 5, and 25 are also frequently involved in canine tumors.[16] Chromosome 1 may contain a gene responsible for tumor development and lead to changes in the karyotype, including fusion of the centromere, or centric fusions.[16] Aneuploidy due to nondisjunction is a common feature in tumor cells.[17]

In humans

[edit]Sex chromosomes

[edit]Some of the most frequent genetic disorders are abnormalities of sex chromosomes, but polysomies rarely occur.[18] 49,XXXXY chromosome polysomy occurs every 1 in 85,000 newborn males.[19] The incidence of other X polysomies (48,XXXX, 48,XXXY, 48,XXYY) is more rare than 49,XXXXY.[20] Polysomy Y (47,XYY; 48,XYYY; 48,XXYY; 49,XXYYY) occurs in 1 out of 975 males and may cause psychiatric, social, and somatic abnormalities.[21] Polysomy X may cause mental and developmental retardation and physical malformation. Klinefelter syndrome is an example of human polysomy X with the karyotype 47, XXY. X chromosome polysomies can be inherited from either a single maternal (49, X polysomies) or paternal (48, X polysomies) X chromosome.[18] Polysomy of sex chromosomes is caused by successive nondisjunctions in meiosis I and II.[6]

Chromosome 7

[edit]

In squamous cell carcinoma, a protein from the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene is often overexpressed in conjunction with polysomy of chromosome 7, so chromosome 7 can be used to predict the presence of EGFR in squamous cell carcinoma.[22] In colorectal cancer, EGFR expression is decreased with polysomy 7, which makes polysomy 7 easier to detect and could be used to prevent patients from having unnecessary cancer treatment.[23]

Chromosome 8

[edit]

Tetrasomy and hexasomy 8 are rare compared to trisomy 8, which is the most common karyotypic finding in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).[24] AML, MDS, or myeloproliferative disorder (MPD) with a high incidence of secondary diseases and a six-month survival rate are associated with a polysomy 8 syndrome.[25]

Chromosome 17

[edit]Overexpression of the HER2/neu gene on chromosome 17 and some type of polysomy has been reported in 8-68% of breast carcinomas.[26] If theHER-2/neu gene does not amplify in the case of polysomy, proteins may be overexpressed and could lead to tumerogenesis.[27] Polysomy 17 may complicate the interpretation of HER2 testing results in cancer patients. Chromosome 17 polysomy may not be present when the centromere is amplified, so it was later discovered that polysomy 17 is rare. This was discovered using array comparative genomic hybridization, a DNA-based alternative for clinical evaluation of HER2 gene copy number.[28]

Trisomy 21

[edit]

Trisomy 21 is a form of Down syndrome that occurs when there is an extra copy of chromosome 21. The result is a genetic condition in which a person has 47 chromosomes instead of the usual 46. During egg or sperm development the 21st chromosome does not separate during either the egg or sperm development. The result is a cell that has 24 chromosomes. This extra chromosome may cause problems with the manner in which the body and brain develop.[29]

Tetrasomy 9p

[edit]Tetrasomy 9p is a rare condition in which people have a small extra chromosome that contains two copies of part of chromosome 9, in addition to having two normal chromosome 9's as well. This condition may be diagnosed by analyzing a person's blood sample since 9p is found in high concentrations in the blood. Ultrasound is another tool that may be utilized to identify tetrasomy 9p in infants prior to birth. Prenatal ultrasound may reveal several common characteristics including: growth restriction, ventriculomegaly, cleft lip or palate, and renal anomalies.[30]

Tetrasomy 18p

[edit]Tetrasomy 18p occurs when the short arm of the 18th chromosome appears four times, rather than twice, in the cells of the body. It is considered to be a rare disease and usually is not inherited. The mechanism of 18p formation appears to be the result of two independent events: centromeric misdivision and nondisjunction.[31] Characteristic features of tetrasomy 18p include, but are not limited to: growth retardation, scoliosis, abnormal brain MRI, developmental delays, and strabismus.[31]

In insects

[edit]Germ line polysomy in the grasshopper

[edit]

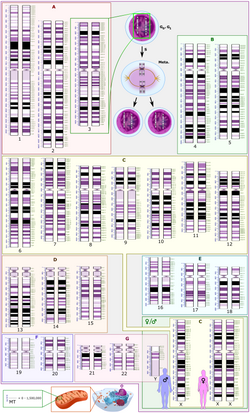

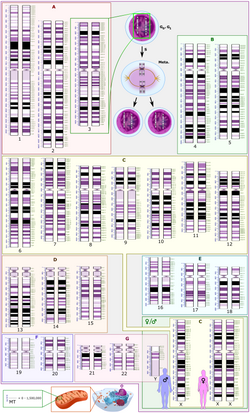

Germ line cells develop into eggs and sperm and the associated inherited material can be passed down to future generations.[32] As shown in the associated karyotype image, chromosomes 1–22 are grouped A-G. A population of male grasshoppers (Chorthippus binotatus) from the Sierra Nevada (Spain) are polysomic mosaics (coming from cells of two genetically different types) possessing an extra E group chromosome(chromosomes 16, 17 & 18) in their testicles.[33] Parents that exhibited polysomy did not pass the E chromosome abnormality to any of the offspring, so this is not something that is passed down to future generations.[33] Male grasshoppers (Atractomorpha similis) from Australia carry between one and ten extra copies of chromosome A9, with one being the most common in natural populations.[34] Most polysomic males produce normal sperm. However, polysomy can be transmissible through both the male and female parents through nondisjunction.[34]

Heterochromatic polysomy in the cricket

[edit]Heterochromatin contains a small number of genes and densely staining nodules in or along chromosomes.[35] The mole cricket chromosome number varies between 19 and 23 chromosomes depending on the part of the world in which they are located, including Jerusalem, Palestine, and Europe.[36] Heterochromic polysomy is seen in mole crickets with 23 chromosomes and may be a factor contributing to their evolution, specifically within the species Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa, along with various living environments and mating systems.[36][37]

X-chromosome polysomy in the fruit fly

[edit]In the fruit fly, Drosophila, one X chromosome in the male is almost the same as two X chromosomes in the female in terms of the gene product produced.[38] Despite this, metafemales, or females having three X chromosomes, are unlikely to survive.[38] It is possible that the extra X chromosome decreases gene expression and could explain why the metafemales rarely survive this X-chromosome polysomy.[38]

In plants

[edit]A karyotype rearrangement of individual chromosomes takes place when polysomy in plants is observed. The mechanism of this type of rearrangement is "non-disjunction, mis-segregation in diploids or polyploids; mis-segregation from multivalents in interchange heterozygotes."[39] Incidences of polysomy have been identified in many species of plants, including:

In fungi

[edit]

Few fungi have been researched so far, possibly due to the low number of chromosomes in fungi, as determined by pulsed field gel electrophoresis.[46] Polysomy of Chromosome 13 has been observed in the Flor strains of the yeast species Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Chromosome 13 contains loci, specifically the ADH2 and ADH3 loci, which encode for the isozymes of alcohol dehydrogenase. These isozymes play a primary role in the biological aging of wines via ethanol oxidative utilization.[47] Polysomy of Chromosome 13 is promoted when there is disruption of the yeast RNA1 gene with LEU2 sequences.[48]

Diagnostic tools

[edit]

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

[edit]Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is a cytogenetic technique that has proven to be useful in the diagnosis of patients with polysomy.[49] Conventional cytogenetics and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) have been used to detect various polysomies, including the most common autosomies (trisomy 13, 18, 21) as well as polysomy X and Y.[50] Testing for chromosomal aneuploidy with Fluorescence in situ hybridization may increase the sensitivity of cytology and improve the accuracy of cancer diagnosis.[51] The Cervical Cancer, TERC, Fluorescence in situ hybridization test, detects amplification of the human telomerase RNA component (TERC) gene and/or polysomy of chromosome 3.[52]

Spectral karyotyping

[edit]Spectral karyotyping (SKY) looks at the entire karyotype by using fluorescent labels and assigning a particular color to each chromosome. SKY is usually performed after conventional cytogenic techniques have already detected an abnormal chromosome. FISH analysis is then used to confirm the identity of the chromosome.[50]

Giemsa banding (G-banded karyotyping)

[edit]Karyotypes are commonly analyzed using Giemsa banding (G-banded karyotyping). Each chromosome shows unique light and dark bands after they are denatured with trypsin and polysomies can be detected by counting the stained chromosomes. Several cells have to be analysed to detect mosaicism.[53]

Microarray analysis

[edit]Submicroscopic chromosomal abnormalities that are too small to be detected via other means of karyotyping, may be identified by chromosomal microarray analysis.[54] There are several existing microarray techniques that may be utilized during the prenatal diagnosis phase, and these include SNP arrays and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH).[55] CGH is a DNA-based diagnostic tool that has been used to detect polysomy 17 in breast cancer.[27] CGH was first used in 1992 by Kallionemi at UC San Francisco.[56] When used in conjunction with ultrasound findings, microarray analysis may be instrumental in the clinical diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities.

Prenatal diagnostic tests

[edit]Prenatal and other diagnostic techniques such as immunocytochemistry (ICC) evaluation are usually followed by FISH or Polymerase Chain Reaction to detect chromosomal aneuploidies. Maternal blood sampling for fetal cells, often used to identify risk of trisomies 18 or 21, poses less risk as compared to amniocentesis and chorionic villous sampling (CVS).[57] Chorionic villus sampling utilizes placental tissue to give information about fetal chromosome status and has been used since the 1970s.[58] In addition to CVS, amniocentesis can be used to obtain fetal karyotype by examining fetal cells in amniotic fluid. It was first performed in 1952 and became standard practice in the 1970s.[59] The odds of having a child with polysomy increases as the age of the mother increases, so pregnant women over the age of 35 are tested.[60]

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis

[edit]RFLPs can be used to determine the origin and mechanism involved with Polysomy X and other chromosome heteromorphisms or chromosomes that differ in size, shape, or staining properties. Restriction enzymes cut DNA at a specific site and the DNA fragments that are left are called restriction fragment length polymorphisms, or RFLPs.[61] RFLP also aids in the identification of the Huntingtin (HTT) gene which is predictive of an adult-onset autosomal disorder called Huntington's disease (HD). Mutations in chromosome 4 are able to be visualized when RFLP is used in conjunction with Southern blot analysis.[62]

Flow cytometry

[edit]Human lymphocyte cultures may be analyzed by flow cytometry to assess chromosomal abnormalities, such as polyploidy, hypodiploidy, and hyperdiploidy.[63] Flow cytometers have the ability to analyze thousands of cells each second and are commonly used to isolate specific cell populations.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Rieger, R.; Michaelis, A.; Green, M.M. (1968). A glossary of genetics and cytogenetics: Classical and molecular. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- ^ White, Michael James Denham (1937). The Chromosomes. London: Methuen & Co., Ltd. p. 55.

- ^ a b Griffiths, AJF; Miller JH; Suzuki DT; et al. (2000). An Introduction to Genetic Analysis: Aneuploidy (7th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman & Co. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2014.[page needed]

- ^ Anthony J. F. Griffiths (1999). An introduction to genetic analysis (7. ed., 1. print. ed.). New York: Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-3520-5. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018.[page needed]

- ^ Calvieri F, Tozzi C, Benincori C, et al. (August 1988). "Partial tetrasomy 9 in an infant with clinical and radiological evidence of multiple joint dislocations". European Journal of Pediatrics. 147 (6): 645–8. doi:10.1007/bf00442483. PMID 3181206. S2CID 20302464.

- ^ a b Celik A, Eraslan S, Gökgöz N, et al. (June 1997). "Identification of the parental origin of polysomy in two 49,XXXXY cases". Clinical Genetics. 51 (6): 426–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1997.tb02504.x. PMID 9237509. S2CID 34190928.

- ^ Huang B, Bartley J (September 2003). "Partial hexasomy of chromosome 15". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 121A (3): 277–80. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.20182. PMID 12923871. S2CID 41001200.

- ^ Fabarius A, Li R, Yerganian G, Hehlmann R, Duesberg P (January 2008). "Specific clones of spontaneously evolving karyotypes generate individuality of cancers". Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 180 (2): 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2007.10.006. PMID 18206533.

- ^ Ludwig A, Belfiore NM, Pitra C, Svirsky V, Jenneckens I (July 2001). "Genome duplication events and functional reduction of ploidy levels in sturgeon (Acipenser, Huso and Scaphirhynchus)". Genetics. 158 (3): 1203–15. doi:10.1093/genetics/158.3.1203. PMC 1461728. PMID 11454768.

- ^ Schachter M (1949). "[Nanosomy by congenital skeletal polydystrophy – correlation with a maternal gestational deficiency]". Athena (in Italian). 15 (6): 141–3. PMID 15409638.

- ^ Mori M, Matsushita A, Takiuchi Y, et al. (July 2010). "Histiocytic sarcoma and underlying chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: a proposal for the developmental classification of histiocytic sarcoma". International Journal of Hematology. 92 (1): 168–73. doi:10.1007/s12185-010-0603-z. PMID 20535595. S2CID 25682085.

- ^ a b Reimann-Berg N, Willenbrock S, Murua Escobar H, et al. (2011). "Two new cases of polysomy 13 in canine prostate cancer". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 132 (1–2): 16–21. doi:10.1159/000317077. PMID 20668368. S2CID 24726737.

- ^ Winkler S, Murua Escobar H, Reimann-Berg N, Bullerdiek J, Nolte I (2005). "Cytogenetic investigations in four canine lymphomas". Anticancer Research. 25 (6B): 3995–8. PMID 16309190.

- ^ Hahn, KA; Richardson, RC; Hahn, EA; Chrisman, CL (Sep 1994). "Diagnostic and prognostic importance of chromosomal aberrations identified in 61 dogs with lymphosarcoma". Veterinary Pathology. 31 (5): 528–40. doi:10.1177/030098589403100504. PMID 7801430.

- ^ Yang F, Graphodatsky AS, O'Brien PC, et al. (2000). "Reciprocal chromosome painting illuminates the history of genome evolution of the domestic cat, dog and human". Chromosome Research. 8 (5): 393–404. doi:10.1023/A:1009210803123. PMID 10997780. S2CID 19318062.

- ^ a b Winkler S, Reimann-Berg N, Murua Escobar H, et al. (September 2006). "Polysomy 13 in a canine prostate carcinoma underlining its significance in the development of prostate cancer". Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 169 (2): 154–8. doi:10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.03.015. PMID 16938574.

- ^ Winkler S, Murua Escobar H, Eberle N, Reimann-Berg N, Nolte I, Bullerdiek J (2005). "Establishment of a cell line derived from a canine prostate carcinoma with a highly rearranged karyotype". The Journal of Heredity. 96 (7): 782–5. doi:10.1093/jhered/esi085. PMID 15994418.

- ^ a b Leal CA, Belmont JW, Nachtman R, Cantu JM, Medina C (October 1994). "Parental origin of the extra chromosomes in polysomy X". Human Genetics. 94 (4): 423–6. doi:10.1007/bf00201605. PMID 7927341. S2CID 23275179.

- ^ Kleczkowska A, Fryns JP, Van den Berghe H (September 1988). "X-chromosome polysomy in the male. The Leuven experience 1966–1987". Human Genetics. 80 (1): 16–22. doi:10.1007/BF00451449. PMID 3417301. S2CID 7308546.

- ^ de Grouchy J, Turleau C (October 1986). "Microcytogenetics 1984". Experientia. 42 (10): 1090–7. doi:10.1007/BF01941282. PMID 3533601. S2CID 32070898.

- ^ Elias, Sherman; Shulman, Lee P. (2009). "Males with Polysomy Y and Females with Polysomy X". The Global Library of Women's Medicine. doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10358. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Couceiro P, Sousa V, Alarcão A, Silva M, Carvalho L (2010). "Polysomy and amplification of chromosome 7 defined for EGFR gene in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung together with exons 19 and 21 wild type". Revista Portuguesa de Pneumologia. 16 (3): 453–62. doi:10.1016/s2173-5115(10)70049-x. hdl:10316/102760. PMID 20635059.

- ^ Li YH, Wang F, Shen L, et al. (January 2011). "EGFR fluorescence in situ hybridization pattern of chromosome 7 disomy predicts resistance to cetuximab in KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer patients". Clinical Cancer Research. 17 (2): 382–90. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0208. PMID 20884623.

- ^ Paulsson K, Johansson B (February 2007). "Trisomy 8 as the sole chromosomal aberration in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes". Pathologie-biologie. 55 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1016/j.patbio.2006.04.007. PMID 16697122.

- ^ Beyer V, Mühlematter D, Parlier V, et al. (July 2005). "Polysomy 8 defines a clinico-cytogenetic entity representing a subset of myeloid hematologic malignancies associated with a poor prognosis: report on a cohort of 12 patients and review of 105 published cases". Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 160 (2): 97–119. doi:10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.12.003. PMID 15993266.

- ^ Schiaovon, BN; Vassallo J; Rocha RM (2011). "Is polysomy 17 an important phenomenon to predict treatment with trastuzumab in breast cancer?". Applied Cancer Research. 31 (4): 138–142. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ a b Yang, Liu; et al. (Dec 15, 2013). "Impact of polysomy 17 on HER2 testing of invasive breast cancer patients". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 7 (1): 163–173. PMC 3885470. PMID 24427336.

- ^ Yeh IT, Martin MA, Robetorye RS, et al. (September 2009). "Clinical validation of an array CGH test for HER2 status in breast cancer reveals that polysomy 17 is a rare event". Modern Pathology. 22 (9): 1169–75. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2009.78. PMID 19448591.

- ^ "Down Syndrome". Medline Plus. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Dhandha, S; Hogge, WA; Surti, U; McPherson, E (Dec 15, 2002). "Three cases of tetrasomy 9p". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 113 (4): 375–80. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.10826. PMID 12457411.

- ^ a b Sebold C, Roeder E, Zimmerman M, Soileau B, Heard P, Carter E, Schatz M, White WA, Perry B, Reinker K, O'Donnell L, Lancaster J, Li J, Hasi M, Hill A, Pankratz L, Hale DE, Cody JD (Sep 2010). "Tetrasomy 18p: report of the molecular and clinical findings of 43 individuals". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 152A (9): 2164–72. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.33597. PMID 20803640. S2CID 19758003.

- ^ Merriam-Webster. "Germ Line". Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ a b Talavera, M.; López-Leon, M. D.; Cabrero, J.; Camacho, J. P. M. (June 1990). "Male germ line polysomy in the grasshopper Chorthippus binotatus: extra chromosomes are not transmitted". Genome. 33 (3): 384–388. doi:10.1139/g90-058.

- ^ a b Peters, G. B. (January 1981). "Germ line polysomy in the grasshopper Atractomorpha similis". Chromosoma. 81 (4): 593–617. doi:10.1007/BF00285852. S2CID 41211400.

- ^ Merriam-Webster. "Heterochromatin". Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ a b Kushnir, Tuviah (February 1952). "Heterochromatic polysomy in Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa L". Journal of Genetics. 50 (3): 361–383. doi:10.1007/BF02986834. S2CID 1793646.

- ^ Nevo E, Beiles A, Korol AB, Robin YI, Pavlicek T, Hamilton W (April 2000). "Extraordinary multilocus genetic organization in mole crickets, Gryllotalpidae". Evolution. 54 (2): 586–605. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00061.x. PMID 10937235. S2CID 198153947.

- ^ a b c Birchler JA, Hiebert JC, Krietzman M (August 1989). "Gene expression in adult metafemales of Drosophila melanogaster". Genetics. 122 (4): 869–79. doi:10.1093/genetics/122.4.869. PMC 1203761. PMID 2503426.

- ^ Gupta, P. K.; T. Tsuchiya. (1991). Chromosome Engineering in Plants: Genetics, Breeding, Evolution. Amsterdam: Eselvier.

- ^ Ruiz Rejón, C.; R. Lozano; M. Ruiz Rejón (1987). "Polysomy and supernumerary chromosomes in Ornithogalum umbellatum L. (Liliaceae)". Genome. 29 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1139/g87-004.

- ^ Ahuja, MR; Neale DB (2002). "Origins of Polyploidy in Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens (D. DON) ENDL.) and Relationship of Coast Redwood to other Genera of Taxodiaceae". Silvae Genetica. 51: 2–3.

- ^ D'Hont, A; Grivet, L; Feldmann, P; Rao, S; Berding, N; Glaszmann, JC (Mar 7, 1996). "Characterisation of the double genome structure of modern sugarcane cultivars (Saccharum spp.) by molecular cytogenetics". Molecular & General Genetics. 250 (4): 405–13. doi:10.1007/bf02174028. PMID 8602157. S2CID 43107532.

- ^ Mun, JH; et al. (2010). "Sequence and structure of Brassica rapa chromosome A3". Genome Biology. 11 (9): R94. doi:10.1186/gb-2010-11-9-r94. PMC 2965386. PMID 20875114.

- ^ Barker, W.R.; M. Kiehn; E. Vitek (1988). "Chromosome numbers in AustralianEuphrasia (Scrophulariaceae)". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 158 (2–4): 161–164. doi:10.1007/bf00936342. S2CID 1881882.

- ^ Zhu, J.M.; LJ Davies; D Cohen; RE Rowland (1994). "Variation in chromosome number in the seedling progeny of a somaclone of Paspalum dilatatum". Cell Research. 4: 65–78. doi:10.1038/cr.1994.7. S2CID 36302051.

- ^ P.M. Kirk; et al. (2008). Ainsworth & Bisby's dictionary of the fungi (10th ed.). Wallingford, Oxon, UK: CABI. ISBN 978-0-85199-826-8.

- ^ Arora, Dilip K., ed. (2004). Handbook of fungal biotechnology (2. ed., rev. and expanded ed.). New York, NY [u.a.]: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-4018-4.

- ^ Atkinson, NS; Hopper, AK (Jul 1987). "Chromosome specificity of polysomy promotion by disruptions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA1 gene". Genetics. 116 (3): 371–5. doi:10.1093/genetics/116.3.371. PMC 1203148. PMID 3301528.

- ^ Bangarulingam, SY; Bjornsson, E; Enders, F; Barr Fritcher, EG; Gores, G; Halling, KC; Lindor, KD (Jan 2010). "Long-term outcomes of positive fluorescence in situ hybridization tests in primary sclerosing cholangitis". Hepatology. 51 (1): 174–80. doi:10.1002/hep.23277. PMID 19877179. S2CID 11858431.

- ^ a b Binns, Victoria; Nancy Hsu (20 Jun 2001). "Prenatal Diagnosis". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Jon Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0002291. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ^ Gonda, TA; Glick, MP; Sethi, A; Poneros, JM; Palmas, W; Iqbal, S; Gonzalez, S; Nandula, SV; Emond, JC; Brown, RS; Murty, VV; Stevens, PD (Jan 2012). "Polysomy and p16 deletion by fluorescence in situ hybridization in the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary strictures". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 75 (1): 74–9. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.022. PMID 22100297. S2CID 2012265.

- ^ Heselmeyer-Haddad, K; Sommerfeld, K; White, NM; Chaudhri, N; Morrison, LE; Palanisamy, N; Wang, ZY; Auer, G; Steinberg, W; Ried, T (Apr 2005). "Genomic amplification of the human telomerase gene (TERC) in pap smears predicts the development of cervical cancer". The American Journal of Pathology. 166 (4): 1229–38. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62341-3. PMC 1602397. PMID 15793301.

- ^ Yunis JJ, Sanchez O (1973). "G-banding and chromosome structure". Chromosoma. 44 (1): 15–23. doi:10.1007/BF00372570. PMID 4130183. S2CID 8711896.

- ^ "The Use of Chromosomal Microarray Analysis in Prenatal Diagnosis". American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ Shaffer, LG; Rosenfeld, JA; Dabell, MP; Coppinger, J; Bandholz, AM; Ellison, JW; Ravnan, JB; Torchia, BS; Ballif, BC; Fisher, AJ (Oct 2012). "Detection rates of clinically significant genomic alterations by microarray analysis for specific anomalies detected by ultrasound". Prenatal Diagnosis. 32 (10): 986–95. doi:10.1002/pd.3943. PMC 3509216. PMID 22847778.

- ^ Burnett, David; Crocker, John, eds. (2005). The science of laboratory diagnosis (2 ed.). Chichester: Wiley. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-470-85912-4.

- ^ Calabrese, G; Baldi, M; Fantasia, D; Sessa, MT; Kalantar, M; Holzhauer, C; Alunni-Fabbroni, M; Palka, G; Sitar, G (Aug 2012). "Detection of chromosomal aneuploidies in fetal cells isolated from maternal blood using single-chromosome dual-probe FISH analysis". Clinical Genetics. 82 (2): 131–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01775.x. PMID 21895636. S2CID 34089887.

- ^ Ross, Helen L.; Elias, Sherman (1997). "Maternal Serum Screening for Fetal Genetic Disorders". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 24 (1): 33–47. doi:10.1016/S0889-8545(05)70288-6. PMID 9086517.

- ^ Sherman, Elias (2013). "Amniocentesis". Genetic Disorders and the Fetus. Springer. pp. 31–52. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-5155-9_2. ISBN 978-1-4684-5157-3.

- ^ Simpson, Joe Leigh (1990). "Incidence and timing of pregnancy losses: Relevance to evaluating safety of early prenatal diagnosis". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 35 (2): 165–173. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320350205. PMID 2178414.

- ^ Deng, Han-Xiang; Abe, Kyohko; Kondo, Ikuko; Tsukahara, Masato; Inagaki, Haruyo; Hamada, Isamu; Fukushima, Yoshimitsu; Niikawa, Norio (1991). "Parental origin and mechanism of formation of polysomy X: an XXXXX case and four XXXXY cases determined with RFLPs". Human Genetics. 86 (6): 541–4. doi:10.1007/BF00201538. PMID 1673956. S2CID 11111874.

- ^ Chial, Heidi. "Huntington's disease: The discovery of the Huntingtin gene". Nature Education. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ^ Muehlbauer PA, Schuler MJ (August 2005). "Detection of numerical chromosomal aberrations by flow cytometry: a novel process for identifying aneugenic agents". Mutation Research. 585 (1–2): 156–69. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2005.05.002. PMID 15996509.

Further reading

[edit]- Gardner, R. J. M., Grant R. Sutherland, and Lisa G. Shaffer. Chromosome Abnormalities and Genetic Counseling. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012.

- Miller, Orlando J., and Eeva Therman. Human Chromosomes. New York: Springer, 2001.

- Schmid, M., and Indrajit Nanda. Chromosomes Today, Volume 14. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 2004.

- Nussbaum, Robert L., Roderick R. McInnes, Huntington F. Willard, Ada Hamosh, and Margaret W. Thompson. Thompson & Thompson Genetics in Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier, 2007.