Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dorsal column–medial lemniscus pathway

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

| Dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathway | |

|---|---|

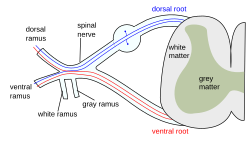

The formation of the spinal nerve from the dorsal and ventral roots. | |

Originating in peripheral sensory receptors, the dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathway transmits fine touch and conscious proprioceptive information to the brain. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Neural tube and crest |

| System | Somatosensory system |

| Decussation | Medial lemniscus |

| To | Sensorimotor cortex |

| Function | Transmit sensation of fine touch, vibration and proprioception |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | via columnae posterioris lemniscique medialis |

| Acronym | DCML |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

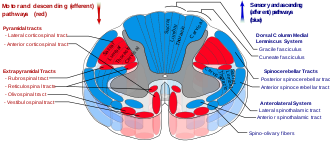

The dorsal column–medial lemniscus pathway (DCML) (also known as the posterior column-medial lemniscus pathway (PCML) is the major sensory pathway of the central nervous system that conveys sensations of fine touch, vibration, two-point discrimination, and proprioception (body position) from the skin and joints. It transmits this information to the somatosensory cortex of the postcentral gyrus in the parietal lobe of the brain.[1][2] The pathway receives information from sensory receptors throughout the body, and carries this in the gracile fasciculus and the cuneate fasciculus, tracts that make up the white matter dorsal columns (also known as the posterior funiculi) of the spinal cord. At the level of the medulla oblongata, the fibers of the tracts decussate and are continued in the medial lemniscus, on to the thalamus and relayed from there through the internal capsule and transmitted to the somatosensory cortex. The name dorsal-column medial lemniscus comes from the two structures that carry the sensory information: the dorsal columns of the spinal cord, and the medial lemniscus in the brainstem.

There are three groupings of neurons that are involved in the pathway: first-order neurons, second-order neurons, and third-order neurons. The first-order neurons are sensory neurons located in the dorsal root ganglia, that send their afferent fibers through the two dorsal columns.[3] The first-order axons make contact with second-order neurons of the dorsal column nuclei (the gracile nucleus and the cuneate nucleus) in the lower medulla. The second-order neurons send their axons to the thalamus. The third-order neurons are in the ventral posterolateral nucleus in the thalamus and fibres from these ascend to the postcentral gyrus.

Sensory information from the upper half of the body is received at the cervical level of the spinal cord and carried in the cuneate tract, and information from the lower body is received at the lumbar level and carried in the gracile tract. The gracile tract is medial to the more lateral cuneate tract.

The axons of second-order neurons of the gracile and cuneate nuclei are known as the internal arcuate fibers and when they cross over the midline, at the sensory decussation in the medulla, they form the medial lemniscus which connects with the thalamus; the axons synapse on neurons in the ventral posterolateral nucleus which then send axons to the primary somatosensory cortex in the postcentral gyrus of the parietal lobe. All of the axons in the DCML pathway are rapidly conducting, large, myelinated fibers.[2]

Structure

[edit]

The DCML pathway is made up of the axons of first, second, and third-order sensory neurons, beginning in the dorsal root ganglia. The axons from the first-order neurons form the ascending tracts of the gracile fasciculus, and the cuneate fasciculus (the dorsal columns) which synapse on the second-order neurons in the gracile nucleus and the cuneate nucleus known together as the dorsal column nuclei; axons from these neurons ascend as the internal arcuate fibers; the fibers cross over at the sensory decussation and form the medial lemniscus which connects with the thalamus; the axons synapse on neurons in the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus, which then send axons to the postcentral gyrus in the parietal lobe.

The gracile fasciculus carries sensory information from the lower half of the body, i.e. the nerves entering the spinal cord below T6. The cuneate fasciculus carries sensory information from the upper half of the body (upper limbs, trunk, neck, and the posterior third of the scalp), i.e. the nerves entering the spinal cord at or above T6.[4] Note that sensory information from the face and anterior 2/3 of the scalp is not carried by the dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathway but by the trigeminal lemniscus tract.

The gracile fasciculus is wedge-shaped on transverse section and lies next to the posterior median septum. Its base is at the surface of the spinal cord, and its apex directed toward the posterior gray commissure. The gracile fasciculus increases in size from inferior to superior.

The cuneate fasciculus is triangular on transverse section and lies between the gracile fasciculus and the posterior column, its base corresponding with the surface of the spinal cord. Its fibers, larger than those of the gracile fasciculus, are mostly derived from the same source, viz., the posterior nerve roots. Some ascend for only a short distance in the tract, and, entering the gray matter, come into close relationship with the cells of the dorsal nucleus, while others can be traced as far as the medulla oblongata, where they end in the gracile nucleus and cuneate nucleus.

The two ascending tracts meet at the level of the sixth thoracic vertebra (T6). Ascending tracts typically have three levels of neurons, namely first-order, second-order, and third-order neurons, that relay information from the physical point of reception to the actual point of interpretation in the brain.

First-order neurons

[edit]Periphery and spinal cord

[edit]

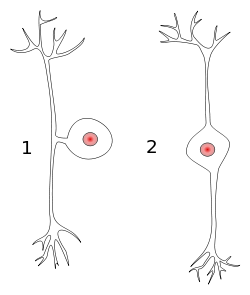

When an action potential is generated by a mechanoreceptor in the tissue, the action potential will travel along the peripheral axon of the first-order neuron. The first-order neuron is pseudounipolar in shape with its body in the dorsal root ganglion. The action signal will continue along the central axon of the neuron through the posterior root, into the posterior horn, and up the posterior column of the spinal cord.

Axons from the lower body enter the posterior column below the level of T6 and travel in the midline section of the column called the gracile fasciculus.[5] Axons from the upper body enter at or above T6 and travel up the posterior column on the outside of the gracile fasciculus in a more lateral section called the cuneate fasciculus. These fasciculi are in an area of white matter, the posterior funiculus (a funiculus) that lies between the posterolateral and the posterior median sulcus. They are separated by a partition of glial cells which places them on either side of the posterior intermediate sulcus.

The column reaches the junction between the spinal cord and the medulla oblongata, where lower body axons in the gracile fasciculus connect (synapse) with neurons in the gracile nucleus, and upper body axons in the cuneate fasciculus synapse with neurons in the cuneate nucleus.[6]

First-order neurons secrete substance P in the dorsal horn as a chemical mediator of pain signaling. The dorsal horn of the spinal cord transmits pain and non-noxious signals from the periphery to the spinal cord itself. Adenosine is another local molecule that modulates dorsal horn pain transmission [3]

Second-order neurons

[edit]Brainstem

[edit]The neurons in these two nuclei (the dorsal column nuclei) are second-order neurons.[6] Their axons cross over to the other side of the medulla and are now named as the internal arcuate fibers, that form the medial lemniscus on each side. This crossing over is known as the sensory decussation.

At the medulla, the medial lemniscus is orientated perpendicular to the way the fibres travelled in their tracts in the posterior column. For example, in the column, lower limb is medial, upper limb is more lateral. At the medial lemniscus, axons from the leg are more ventral, and axons from the arm are more dorsal. Fibres from the trigeminal nerve (supplying the head) come in dorsal to the arm fibres, and travel up the lemniscus too.

The medial lemniscus rotates 90 degrees at the pons. The secondary axons from neurons giving sensation to the head, stay at around the same place, while the leg axons move outwards.

The axons travel up the rest of the brainstem, and synapse at the thalamus (at the ventral posterolateral nucleus for sensation from the neck, trunk, and extremities, and at the ventral posteromedial nucleus for sensation from the head).

Third-order neurons

[edit]Thalamus to cortex

[edit]Axons from the third-order neurons in the ventral posterior nucleus in the thalamus, ascend the posterior limb of the internal capsule. Those originating from the head and the leg swap their relative positions. The axons synapse in the primary somatosensory cortex, with lower body sensation most medial (e.g., the paracentral lobule) and upper body more lateral.

Function

[edit]Discriminative sensation is well developed in the fingers of humans and allows the detection of fine textures. It also allows for the ability known as haptic perception (stereognosis), to determine what an unknown object is, using the hands without visual or audio input. Fine touch is detected by cutaneous receptors called tactile corpuscles that lie in the dermis of the skin close to the epidermis. When these structures are stimulated by slight pressure, an action potential is started. Alternatively, proprioceptive muscle spindles and other skin surface touch mechanoreceptors such as Merkel cells, bulbous corpuscles, lamellar corpuscles, and hair follicle receptors (peritrichial endings) may involve the first neuron in this pathway.

The sensory neurons in this pathway are pseudounipolar, meaning that they have a single process emanating from the cell body with two distinct branches: one peripheral branch that functions somewhat like a dendrite of a typical neuron by receiving input (although it should not be confused with a true dendrite), and one central branch that functions like a typical axon by carrying information to other neurons (again, both branches are actually part of one axon).

Clinical significance

[edit]Damage to the dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathway below the crossing point of its fibers results in loss of vibration and joint sense (proprioception) on the same side of the body as the lesion. Damage above the crossing point result a loss of vibration and joint sense on the opposite side of the body to the lesion. The pathway is tested with Romberg's test.

Damage to either of the dorsal column tracts can result in the permanent loss of sensation in the limbs. See Brown-Séquard syndrome.

Additional information

[edit]The cuneate fasciculus, fasciculus cuneatus, cuneate tract, tract of Burdach, was named for Karl Friedrich Burdach. The gracile fasciculus, the tract of Goll, was named after Swiss neuroanatomist Friedrich Goll (1829–1903).

See also

[edit]- Spinothalamic tract (Anterolateral system)

References

[edit]- ^ Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 8/8ch5/s8ch5_22". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

- ^ a b O'Sullivan, S. B., & Schmitz, T. J. (2007). Physical Rehabilitation (5th Edition ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company.

- ^ a b Giuffrida, R; Rustioni, A (1992). "Dorsal root ganglion neurons projecting to the dorsal column nuclei of rats". J. Comp. Neurol. 316 (2): 206–20. doi:10.1002/cne.903160206. PMID 1374085. S2CID 20445258.

- ^ Purves, Dale (2011). Neuroscience (5th ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer. pp. 198–200. ISBN 9780878936953.

- ^ Luria, V; Laufer, E (Jul 2, 2007). "Lateral motor column axons execute a ternary trajectory choice between limb and body tissues". Neural Development. 2: 13. doi:10.1186/1749-8104-2-13. PMC 1949814. PMID 17605791.

- ^ a b Boitano, Scott; Brooks, Heddwen L.; Barman, Susan M.; Barrett, Kim E. (2015-10-28). Ganong's Review of Medical Physiology. McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 168–170. ISBN 9780071825108.

External links

[edit]- "Somatosensory Pathways". The Major Systems: Sensory Systems - Somatosensory System. U Alberta. Apr 9, 2002.