Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Prohibited airspace

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A prohibited airspace is an area (volume) of airspace within which flight of aircraft is not allowed, usually due to security concerns. It is one of many types of special use airspace designations and is depicted on aeronautical charts with the letter "P" followed by a serial number. It differs from restricted airspace in that entry is typically forbidden at all times from all aircraft and is not subject to clearance from ATC or the airspace's controlling body.

According to the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA): "Restricted Areas contain airspace of defined dimensions identified by an area on the surface of the earth within which the flight of aircraft is prohibited. Such areas are established for security or other reasons associated with the national welfare. These areas are published in the Federal Register and are depicted on aeronautical charts."

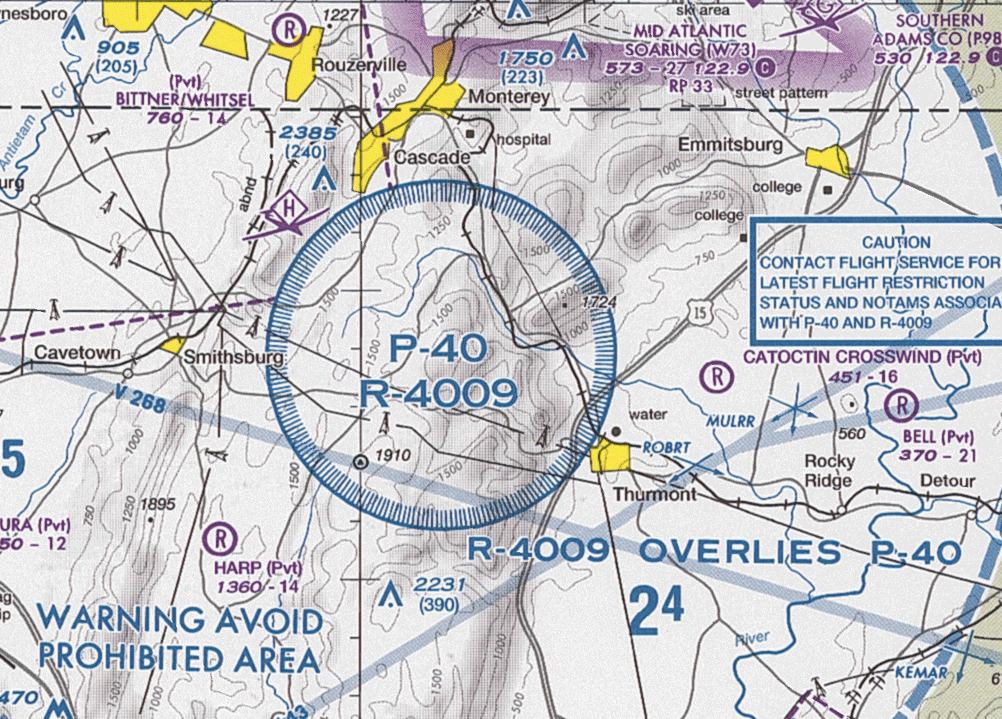

Some prohibited airspace may be supplemented via NOTAMs. For example, Prohibited Area 40 (P-40) and Restricted Area 4009 (R4009) often have additional restricted airspace added via a NOTAM when the president of the United States visits Camp David in Maryland, while normally the airspace outside of P-40 and R4009 is not prohibited/restricted.

Violating prohibited airspace established for national security purposes may result in military interception and/or the possibility of an attack upon the violating aircraft, or if this is avoided then large fines and jail time are often incurred. Aircraft violating or about to violate prohibited airspace are often warned beforehand on 121.5 MHz, the emergency frequency for aircraft.

List of prohibited airspaces

[edit]Australia

[edit]- Australia currently has no prohibited airspaces.[1] Previously, The Pine Gap Joint Defence Facility near Alice Springs was designated as a permanent no-fly zone. This airspace has since been changed to a restricted area (RA3).

China

[edit]- Tiananmen Square

- All flights in and out of Taiwan by Taiwanese air carriers (only allowed to fly over Yunnan, Guangxi, Guangdong, Hainan, Hong Kong, Macau), unless the aircraft stops over at a Chinese airport.

- New China-US airline routes are barred from using Russian airspace as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[2]

Cuba

[edit]- Unscheduled foreign aircraft are prohibited from entering or encroaching Cuban airspace including disputed international water zones except when permission has been explicitly given by the Cuban Government. The Cuban military has been known to shoot down and destroy unauthorised aircraft without warning including a 1996 incident in which two U.S.-registered aircraft were shot down and destroyed by Cuban Air Force MiGs.[3]

Finland

[edit]- Loviisa Nuclear Power Plant, Loviisa[4]

- Olkiluoto Nuclear Power Plant, Eurajoki[4]

- Kilpilahti oil refinery, Porvoo[4]

- Munkkiniemi, Helsinki[4]

- Kruununhaka, Helsinki[4]

- Meilahti, Helsinki[4]

- Luonnonmaa, Naantali[4]

- Hanhikivi Nuclear Power Plant, Pyhäjoki[4]

France

[edit]- All traffic is prohibited above Paris. Exceptions include military aircraft and civil aeroplanes flying no lower than 6,500 feet (2,000 m).[5] Authorisations are either given by the Ministry of Defence, for military aircraft, or by the Paris Police Prefecture and the Directorate General for Civil Aviation for civil ones. Moreover, the flying of helicopters within the limits of Paris (designated the Boulevard Périphérique) is also forbidden. Special authorisation can be granted by the Prefecture of Police for helicopters undertaking precise missions such as police air-surveillance, air ambulances but also transport of high-profile personalities.

- Although not within Paris boundaries, the business district of La Défense has been placed under prohibited airspace in response to 9/11.[6]

Greece

[edit]- All traffic is prohibited above the Parthenon below 5,000 feet (1,500 m). This includes aircraft departing from Eleftherios Venizelos International Airport.

Hungary

[edit]- Budapest (Inner city and Buda Hills)

- Hungarian Parliament Building, including the heavily protected Holy Crown of Hungary

- Buda Castle, including Sándor Palace (home to the president and his family)

- Hungarian National Bank HQ

- Hungarian National Museum

- Saint Stephen's Basilica, including the heavily protected Holy Right, the right hand of Saint Stephen (the founder of Hungary)

- Atomic bunker F4

- Research reactor of the MTA Central Physical Research Institute in Buda Hills

- Paks (area around Paks Nuclear Power Plant)

- Bases of the Hungarian Homeland Defence Forces through the country (including Kecskemét Air Base, Pápa Air Base, Szolnok Air Base)

- National parks and holiday resorts (including Lake Balaton and Hortobágy National Park)

India

[edit]- The Rashtrapati Bhavan in Delhi.

- Parliament Building, prime minister's residence, and other important centres in New Delhi.

- The airspace around many Defence and Indian Air Force bases are restricted, although new proposals are suggesting opening them for civilian aircraft.

- Tirumala Venkateswara Temple in Tirupati state of Andhra Pradesh.

- Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Thiruvananthapuram district state of Kerala.

- The Taj Mahal, Agra, State of Uttar Pradesh, India

- The Tower of Silence, Mumbai.

- Mathura Refinery

- Bhabha Atomic Research Centre

- Sriharikota Space Station in Nellore district state of Andhra Pradesh.

- A 10-km radius no-fly zone over Kalpakkam nuclear installation, Tamil Nadu. All flight activity to 10,000 feet (3,000 m) over the Kalpakkam area is prohibited.[9][10]

- Golden Temple in Amritsar, Punjab, India

Iran

[edit]- Shahid Modarres missile base at Bidganeh near Malard, Tehran

Ireland

[edit]Israel

[edit]Due to Arab–Israeli conflict, Israeli aircraft are not allowed to fly over numerous countries. These include:

- Iran

- Lebanon

- Syria

- Iraq

- Pakistan

- Libya

- Tunisia

- Malaysia

- Indonesia

- Yemen

- Algeria

- Mali

- Niger

- Mauritania

- Bangladesh

Pakistan

[edit]- Islamabad – The no-fly zone is specifically along Constitution Avenue in North-east Islamabad, where many important government buildings are located:

- The Parliament Building

- The Presidency (Residence of the President)

- The Prime Minister's Residence

- The Prime Minister's Secretariat

- The Supreme Court

- Kahuta Research Laboratories, Pakistan's main facility for the development of nuclear weapons

- Khushab Nuclear Complex

Peru

[edit]Poland

[edit]- Temporary flight restrictions over any publicly announced event in a stadium (capacity) or plaza (expected attendance) exceeds 20,000 people by a radius of 5 nautical miles (9.2km) under a height of 5,000 feet (1.5km). An additional strict drone usage restriction is in place for PGE Narodowy Stadium in Warsaw, not permitting usage within 500 metres of the stadium. Non-compliance for both private and corporation actors starts with a minimum fine of 10000PLN (2339 EUR in August 2024)

Russia

[edit]Many flights are being regularly routed through the outer regions of this airspace due to the Russo-Ukrainian War.

Since October 25, 2015, Ukrainian aircraft have been prohibited from entering Russian airspace.

After the Western countries banned Russian planes from its skies following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, aircraft registered in or operated by Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, United Kingdom, United States, Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and the European Union member states[12] are banned from using Russian airspace.[13]

On October 30, 2022, Cathay Pacific, a Hong Kong airline, announced that it would resume using Russian airspace on some flights such as the "polar route" from New York to Hong Kong, which had stopped following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[14]

Due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian aircraft are not allowed to fly over numerous countries. These include:

- Andorra

- Australia

- Canada

- European Union member states;

- Austria

- Belgium

- Croatia

- Czech Republic

- Denmark

- Estonia

- Finland

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Hungary

- Ireland

- Italy

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Luxembourg

- Malta

- Netherlands

- Poland

- Portugal

- Slovakia

- Slovenia

- Spain

- Sweden

- Greenland

- Iceland

- Japan

- Liechtenstein

- New Zealand

- Norway

- San Marino

- Singapore

- South Korea

- Switzerland

- Taiwan

- United Kingdom

- United States

Saudi Arabia

[edit]South Korea

[edit]Besides, North Korean aircraft must obtain special approval from South Korean authorities before entering its airspace, and must not enter directly above the Military Demarcation Line (MDL).

Sri Lanka

[edit]According to Air Navigation (Air Defence) Regulation 1 (2007), airspace over the territory and territorial waters of Sri Lanka (except Ruhuna Open Skies Area) are declared an air defence identification zone (ADIZ) with prohibited areas and restricted areas within it. No aircraft may operate in prohibited or restricted areas without valid air defence clearance (ADC) from the Sri Lanka Air Force (SLAF).

Prohibited areas are,[16]

- Colombo City 1 nautical mile (1.9 km) centering the Parliament – Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte

- Sapugaskanda Oil Refinery (0.25 nautical miles, 0.46 km)

- Orugodawatta Petroleum storage tanks. (0.25 nautical miles, 0.46 km)

- Kolonnawa Petroleum storage complex (0.25 nautical miles, 0.46 km)

Restricted areas are,[16]

- Sri Lanka Air Force bases SLAF Anuradhapura, SLAF Hingurakgoda, SLAF Vavuniya, SLAF Palaly and SLAF Sigiriya (5 nautical miles, 9.3 km)

- Jaffna town (5 nautical miles, 9.3 km)

- Trincomalee harbour (5 nautical miles, 9.3 km)

- SLAF China Bay (10 nautical miles, 19 km)

- The garrison town of Diyatalawa (2 nautical miles, 3.7 km)

- Temple of the Tooth, Kandy (2 nautical miles, 3.7 km; earlier 6 nautical miles, 11 km)

Taiwan

[edit]- The area around the Presidential Hall (總統府) and Taipei 101, both located in Taipei.

- Parts of the Taiwan Strait

- The area around the nuclear power plants in Taiwan.

Besides, Mainland China-registered aircraft bearing the Chinese national flag are also prohibited from entering Taiwanese airspace.

Turkey

[edit]Ukraine

[edit]Since October 25, 2015 all traffic by Russian aircraft has been prohibited. As the result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the civilian flights flying over Ukraine and flights to the Ukrainian cities are suspended for the time being.[18]

United Kingdom

[edit]- Sellafield Nuclear Site, Cumbria

- Winfrith nuclear research site

- Atomic Energy Research Establishment Harwell has now been downgraded – see UK CAA

- RNAD Coulport / HMNB Clyde Faslane

- Dounreay Nuclear Power Development Establishment

- Buckingham Palace

- Windsor Castle[19][20]

- Houses of Parliament

- Purple Corridor

- Downing Street

United States

[edit]The FAA issues Temporary Flight Restrictions (TFR) in the form of a Notice to Air Missions (NOTAM) which are effective for the duration of an event, typically a few days or weeks. TFRs are issued for VIP movement such as the president's travels outside Washington, D.C., surface-based hazards to flight such as toxic gas spills or volcanic eruptions, air-shows, military security, and special events including political ones like national party conventions.[21] TFRs have also been issued to ensure a safe environment for firefighting operations in the case of wildfires and for other reasons as necessary. A TFR was quickly issued around the crash site of Cory Lidle's airplane in New York City. Later, a broader TFR was issued to require pilots traveling over the East River to obtain air traffic control clearance.

Permanent prohibited areas

[edit]- Thurmont, Maryland, site of Presidential retreat Camp David (Prohibited Area 40 or P-40)

- Amarillo, Texas, Pantex nuclear assembly plant (P-47)

- Bush Ranch near Crawford, Texas (P-49)

- Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Georgia (P-50)

- Naval Base Kitsap, Washington (P-51)

- Washington, D.C., U.S. Capitol, White House, and Naval Observatory (P-56); see Other restrictions below for information about all Active Prohibited Areas in the Washington D.C./Baltimore Flight Restricted Zone.

- Bush compound near Kennebunkport, Maine (P-67)

- Mount Vernon, Virginia, home of George Washington (P-73)

- Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in northern Minnesota (P-204, 205, and 206)

Temporary restrictions over Disney theme parks were made permanent with language added to a 2003 federal spending bill.[22] Additionally, an indirect TFR prohibits flight below 3,000 feet (910 m) above ground level and within a 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) radius of stadiums with seating capacity of 30,000 or more, in which an World Series, MLS Cup Final, Super Bowl, College Football Playoff National Championship, NASCAR grand slam races, WrestleMania, or the Olympic Games in the United States are taking place, from one hour before to one hour after the event except those sports teams residing and stadiums in Canada.

TFRs over public and corporate venues have been controversial. Groups have questioned whether these last TFRs served a public need, or the needs of politically connected venue operators.[23][24]

Other restrictions

[edit]In addition to areas off limits to civil aviation, a variety of other airspace restrictions exists in the United States. Notable ones include the Flight Restriction Zone (FRZ) encompassing all airspace up to 18,000 feet (5,500 m) within approximately 15 nautical miles (28 km) of Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport around Washington, D.C. Flights within this airspace, while not entirely prohibited, are highly restricted. All pilots flying within the FRZ are required to undergo a background check and fingerprinting. An additional "Special Flight Rules Area" encompassing most of the Baltimore-Washington D.C. metropolitan area requires the filing of a flight plan and communication with air traffic control.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ [Designated Airspace Handbook]. Airservices Australia. Retrieved April 29, 2019

- ^ "Airlines dispute adds headwinds to US-China relationship". Financial Times. 2023-04-29. Archived from the original on 2023-06-27. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ Staff writer (February 24, 1996). "Civilian U.S. Planes Shot Down Near Cuba". CNN. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Valtioneuvoston asetus ilmailulta rajoitetuista alueista". Finlex. December 4, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ "AIRAC 2019-05-23". Archived from the original on 2019-05-25. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- ^ "Espace aérien". Mairie de Paris (in French). Archived from the original on November 26, 2012. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ^ "Hungary all zones below 9500ft / 2900m including green zones – Airspace route planner". www.galatech.hu.

- ^ "Airspace of the Budapest metropolitan area (detailed map)" (PDF).

- ^ Official order by the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (India) dated 16 December 2008 (http://dgca.nic.in/aic/aic14_2008.pdf). Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Kumar, Vinay (17 December 2008). "No-fly zone over Kalpakkam plant". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ "Direction" (PDF). www.iaa.ie. 2004. Retrieved 2020-01-11.

- ^ Aircraft registered in and operated by the Eurozone countries, Czech Republic, Poland, Sweden and Denmark only.

- ^ "Russia to bar people from a growing list of "unfriendly" nations as sanctions over Putin's Ukraine war bite". CBS News. New York: Paramount. AFP. 28 March 2022.

- ^ Shekhawat, Jaiveersingh; Dey, Mrinmay (2022-10-30). "Cathay Pacific to resume some flights in Russian airspace". Reuters. Hong Kong. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ^ "Why Commercial Airplanes Never Fly Over Some Places ?". Archived from the original on 2021-07-09. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- ^ a b "Avigation warnings - prohibited, restricted and danger areas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-03-10.

- ^ "İmralı'nın üzerindeki uçuş yasağının sınırlarını daraltıldı". Habertürk (in Turkish). 11 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Timmins, Beth (24 February 2022). "Ukraine airspace closed to civilian flights". BBC News. Kyiv.

- ^ "Windsor Castle no-fly zone application after security breach". BBC News. 9 January 2022.

- ^ The Air Navigation (Restriction of Flying) (Windsor Castle) (No. 2) Regulations 2018

- ^ "FLIGHT ADVISORY National Special Security Event Republican National Convention Tampa, Florida August 26-30, 2012" (PDF). FAA.

- ^ Pearce, Matt. "No-fly zones over Disney parks face new scrutiny". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles.

- ^ [1] Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine [2]

- ^ "Aircraft Building | EAA". www.eaa.org.