Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

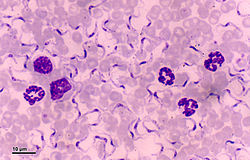

Trypanosomatida

View on Wikipedia

| Trypanosomes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Discoba |

| Phylum: | Euglenozoa |

| Class: | Kinetoplastea |

| Subclass: | Metakinetoplastina |

| Order: | Trypanosomatida Kent 1880 |

| Family: | Trypanosomatidae Doflein 1901 |

| Subfamily | |

| |

Trypanosomatida is a group of kinetoplastid unicellular organisms distinguished by having only a single flagellum. The name is derived from the Greek trypano (borer) and soma (body) because of the corkscrew-like motion of some trypanosomatid species. All members are exclusively parasitic, found primarily in insects.[1] A few genera have life-cycles involving a secondary host, which may be a vertebrate, invertebrate or plant. These include several species that cause major diseases in humans.[2] Some trypanosomatida are intracellular parasites, with the important exception of Trypanosoma brucei.

Medical importance

[edit]The three major human diseases caused by trypanosomatids are; African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness, caused by Trypanosoma brucei and transmitted by tsetse flies[3]), South American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease, caused by T. cruzi and transmitted by triatomine bugs), and leishmaniasis (a set of trypanosomal diseases caused by various species of Leishmania transmitted by sandflies[4]).

Evolution

[edit]The family is known from fossils of the extinct genus Paleoleishmania preserved in Burmese amber dating to the Albian (100 mya) and Dominican amber from the Burdigalian (20–15 mya) of Hispaniola.[5] The genus Trypanosoma is also represented in Dominican amber in the extinct species T. antiquus.[6]

Taxonomy

[edit]Three genera are dixenous (two hosts in the life cycle) – Leishmania, Phytomonas and Trypanosoma, while The remainder are monoxenous (one host in the life cycle).[citation needed] Paratrypanosoma appears to be the first evolving branch in this order. Fifteen genera are recognised in the Trypanosomatidae and there are three subfamilies – Blechomonadinae, Leishmaniinae and Strigomonadinae.[clarification needed] The genera in the subfamily Strigomonadinae are characterised by the presence of obligatory intracellular bacteria of the Kinetoplastibacterium genus.[7]

- Family Trypanosomatidae Calkins 1926 [Trypanomorphidae Woodcock 1906; Trypanosomataceae Senn 1911]

- Genus Agamomonas Grassé 1952

- Genus Batracoleishmania Dasgupta 2011

- Genus Blastocrithidia Laird 1959

- Genus Cercoplasma Roubaud 1911

- Genus Cystotrypanosoma Roubaud 1911

- Genus Jaenimonas Votypka & Hamilton 2015

- Genus Lamellasoma Davis 1947

- Genus Leptowallaceina Podlipaev & Frolov 2000

- Genus Lewisonella Chalmers 1918 nomen dubium

- Genus Malacozoomonas Nicoli, Penaud & Timon-David 1972

- Genus Nematodomonas Nicoli, Penaud & Timon-David 1972

- Genus †Paleoleishmania Poinar & Poinar, 2004

- Genus †Paleotrypanosoma Poinar 2008

- Genus Paramecioides Grassé 1882

- Genus Sauroleishmania Ranque 1973

- Genus Sergeia Svobodová et al. 2007 non Stimpson 1860 non Nasonov 1923 non Sergio Manning & Lemaitre 1994

- Genus Trypanomonas Danilewsky 1885

- Genus Trypanomorpha Woodcock 1906

- Genus Undulina Lankester 187

- Genus Wallaceina Bulat, Mokrousov & Podlipaev 1999 [Proteomonas Podlipaev, Frolov & Kolesnikov 1990 non Hill & Wetherbee 1986]

- Genus Wallacemonas Kostygov & Yurchenko 2014

- Subfamily Paratrypanosomatinae Votýpka & Lukeš 2013

- Genus Paratrypanosoma Votypka & Lukes 2013

- Subfamily Trypanosomatinae

- Genus Trypanosoma Gruby 1843

- Subfamily Blechomonadinae Votypka & Suková 2013

- Genus Blechomonas Votypka & Suková 2013

- Subfamily Leishmaniinae sensu Maslov & Lukeš 2012

- Clade Crithidiatae Maslov & Lukeš 2012

- Genus Crithidia Léger 1902

- Genus Leptomonas Kent 1880

- Genus Lotmaria Schwarz 2015

- Clade Leishmaniatae Maslov & Lukeš 2012

- Genus Borovskyia Kostygov & Yurchenko 2017

- Genus Endotrypanum Mesnil & Brimont 1908

- Genus Leishmania Ross 1903

- Genus Novymonas Votýpka et al. 2015

- Genus Paraleishmania Cupolillo et al. 2000

- Genus Zelonia Shaw, Camargo et Teixeira 2016

- Subfamily Phytomonadinae Kostygov & Yurchenko 2015

- Genus Herpetomonas Kent 1880 non Donovan 1909

- Genus Lafontella Kostygov & Yurchenko 2015

- Genus Phytomonas Donovan 1909

- Subfamily Strigomonadinae Votypka et al. 2014

- Genus Angomonas Souza & Corte-Real 1991

- Genus Kentomonas Votypka et al. 2014

- Genus Strigomonas Lwoff & Lwoff 1931

Life cycle

[edit]Some trypanosomatids only occupy a single host, while many others are heteroxenous: they live in more than one host species over their life cycle. This heteroxenous life cycle typically includes the intestine of a bloodsucking insect and the blood and/or tissues of a vertebrate. Rarer hosts include other bloodsucking invertebrates, such as leeches,[8] and other organisms such as plants. Different species go through a range of different morphologies at different stages of the life cycle, with most having at least two different morphologies. Typically the promastigote and epimastigote forms are found in insect hosts, trypomastigote forms in the mammalian bloodstream and amastigotes in intracellular environments. [citation needed]

Among commonly studied examples, T. brucei, T. congolense, and T. vivax are extracellular, while T. cruzi and Leishmania spp. are intracellular.[9] Trypanosomatids with intracellular stages express δ-amastin proteins on their surfaces.[9] de Paiva et al., 2015 illuminates δ-amastins' roles in intracellular success.[9]

Sexual reproduction

[edit]Trypanosomatids that cause globally known diseases such leishmaniasis (Leishmania species), African trypanosomiasis referred to as sleeping sickness (Trypanosoma brucei), and Chagas disease (Trypanosoma cruzi) were found to be capable of meiosis and genetic exchange.[10] These findings indicate the capability for sexual reproduction in the Trypanosomatida.[10]

Morphologies

[edit]

A variety of different morphological forms appear in the life cycles of trypanosomatids, distinguished mainly by the position, length and the cell body attachment of the flagellum. The kinetoplast is found closely associated with the basal body at the base of the flagellum and all species of trypanosomatid have a single nucleus. Most of these morphologies can be found as a life cycle stage in all trypanosomatid genera however certain morphologies are particularly common in a particular genus. The various morphologies were originally named from the genus where the morphology was commonly found, although this terminology is now rarely used because of potential confusion between morphologies and genus. Modern terminology is derived from the Greek; "mastig", meaning whip (referring to the flagellum), and a prefix which indicates the location of the flagellum on the cell. For example, the amastigote (prefix "a-", meaning no flagellum) form is also known as the leishmanial form as all Leishmania have an amastigote life cycle stage.[citation needed]

- Amastigote (leishmanial).[11] Amastigotes are a common morphology during an intracellular lifecycle stage in a mammalian host. All Leishmania have an amastigote stage of the lifecycle. Leishmania amastigotes are particularly small and are among the smallest eukaryotic cells. The flagellum is very short, projecting only slightly beyond the flagellar pocket.

- Promastigote (leptomonad).[11] The promastigote form is a common morphology in the insect host. The flagellum is found anterior of nucleus emerging directly from the anterior cell body. The kinetoplast is located in front of the nucleus, near the anterior end of the body.

- Epimastigote (crithidial).[11] Epimastigotes are a common form in the insect host and Crithidia and Blastocrithidia, both parasites of insects, exhibit this form during their life cycles. The flagellum exits the cell anterior of nucleus and is connected to the cell body for part of its length by an undulating membrane. The kinetoplast is located between the nucleus and the anterior end.

- Trypomastigote (trypanosomal).[11] This stage is characteristic of the genus Trypanosoma in the mammalian host bloodstream as well as infective metacyclic stages in the fly vector. In trypomastigotes the kinetoplast is near the posterior end of the body, and the flagellum lies attached to the cell body for most of its length by an undulating membrane.

- Opisthomastigote (herpetomonad).[11] A rarer morphology where the flagellum posterior of nucleus, passing through a long groove in the cell.

- Endomastigote.[12] A morphotype where the flagellum does not extend beyond the deep flagellar pocket.

-

Amastigote: False colour SEM micrograph of amastigote form Leishmania mexicana. The cell body is shown in orange and the flagellum is in red. 219 pixels/μm.

-

Promastigote: False colour SEM micrograph of promastigote form Leishmania mexicana. The cell body is shown in orange and the flagellum is in red. 119 pixels/μm.

-

Trypomastigote: False colour SEM micrograph of procyclic form Trypanosoma brucei. The cell body is shown in orange and the flagellum is in red. 84 pixels/μm.

Other features

[edit]Notable characteristics of trypanosomatids are the ability to perform trans-splicing of RNA and possession of glycosomes, where much of their glycolysis is confined to. The acidocalcisome, another organelle, was first identified in trypanosomes.[13]

Bacterial endosymbiont

[edit]

| Kinetoplastibacterium | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Pseudomonadati |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Betaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Burkholderiales |

| Family: | Alcaligenaceae |

| Genus: | Ca. "Kinetoplastibacterium" Du et al., 1994 |

Six species of trypanosomatids are known to carry an additional proteobacterial endosymbiont, termed TPE (trypanosomatid proteobacterial endosymbionts). These trypanosomatids (Strigomonas oncopelti, S. culicis, S. galati, Angomonas desouzai, and A. deanei) are in turn known as SHTs, for symbiont-harboring trypanosomatids. All such symbionts have a shared evolutionary origin and are classified in the Candidatus genus "Kinetoplastibacterium".[7]

As with many symbionts, the bacteria have a much reduced genome compared to their free-living relatives of genera Taylorella and Achromobacter. (GTDB finds the genus sister to Proftella, a symbiont of Diaphorina citri.)[14] Reflecting their inability to live alone, they have lost genes dedicated to essential biological functions, relying on the host instead. They have modified their division to become synchronized with the host. In S. culicis at least, the TPE helps the host by synthesizing heme[7] and producing essential enzymes, staying tethered to the kinetoplast.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ Podlipaev S (May 2001). "The more insect trypanosomatids under study-the more diverse Trypanosomatidae appears". International Journal for Parasitology. 31 (5–6): 648–52. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00139-4. PMID 11334958.

- ^ Simpson AG, Stevens JR, Lukes J (April 2006). "The evolution and diversity of kinetoplastid flagellates". Trends in Parasitology. 22 (4): 168–74. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2006.02.006. PMID 16504583.

- ^ "Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness)". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^

- Rêgo, Felipe D.; Soares, Rodrigo Pedro (2021). "Lutzomyia longipalpis: an update on this sand fly vector". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 93 (3): e20200254. doi:10.1590/0001-37652021XXXX. hdl:11336/166702. PMID 33950136. S2CID 233743387. e20200254.

- This review cites this research.

- Abbasi, Ibrahim; Trancoso Lopo de Queiroz, Artur; Kirstein, Oscar David; Nasereddin, Abdelmajeed; Horwitz, Ben Zion; Hailu, Asrat; Salah, Ikram; Mota, Tiago Feitosa; Fraga, Deborah Bittencourt Mothé (2018-11-13). "Plant-feeding phlebotomine sand flies, vectors of leishmaniasis, prefer Cannabis sativa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (46): 11790–11795. Bibcode:2018PNAS..11511790A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810435115. PMC 6243281. PMID 30373823. S2CID 53112660.

- ^ Poinar, G. (2008). "Lutzomyia adiketis sp. n. (Diptera: Phlebotomidae), a vector of Paleoleishmania neotropicum sp. n. (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) in Dominican amber". Parasites & Vectors. 1 (1): 22. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-1-22. PMC 2491605. PMID 18627624.

- ^ Poinar, G. (2005). "Triatoma dominicana sp. n. (Hemiptera: Reduviidae: Triatominae), and Trypanosoma antiquus sp. n. (Stercoraria: Trypanosomatidae), the First Fossil Evidence of a Triatomine-Trypanosomatid Vector Association". Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 5 (1): 72–81. doi:10.1089/vbz.2005.5.72. PMID 15815152.

- ^ a b c Alves, JM; Serrano, MG; Maia da Silva, F; Voegtly, LJ; Matveyev, AV; Teixeira, MM; Camargo, EP; Buck, GA (2013). "Genome evolution and phylogenomic analysis of Candidatus Kinetoplastibacterium, the betaproteobacterial endosymbionts of Strigomonas and Angomonas". Genome Biology and Evolution. 5 (2): 338–50. doi:10.1093/gbe/evt012. PMC 3590767. PMID 23345457.

- ^ Hamilton, P. B.; Stevens, J. R.; Gidley, J.; Holz, P.; Gibson, W. C. (April 2005). "A new lineage of trypanosomes from Australian vertebrates and terrestrial bloodsucking leeches (Haemadipsidae)". International Journal for Parasitology. 35 (4): 431–443. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.12.005. PMID 15777919.

- ^ a b c Silva Pereira, Sara; Trindade, Sandra; De Niz, Mariana; Figueiredo, Luisa M. (2019). "Tissue tropism in parasitic diseases". Open Biology. 9 (5) 190036. doi:10.1098/rsob.190036. PMC 6544988. PMID 31088251.

- ^ a b Silva, Verônica Santana da; Machado, Carlos Renato (2022). "Sex in protists: A new perspective on the reproduction mechanisms of trypanosomatids". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 45 (3): e20220065. doi:10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2022-0065. PMC 9552303. PMID 36218381.

- ^ a b c d e Hoare, Cecil A.; Wallace, Franklin G. (1966). "Developmental Stages of Trypanosomatid Flagellates: a New Terminology". Nature. 212 (5068): 1385–6. Bibcode:1966Natur.212.1385H. doi:10.1038/2121385a0. S2CID 4164112.

- ^ Merzlyak, Ekaterina; Yurchenko, Vyacheslav; Kolesnikov, Alexander A.; Alexandrov, Kirill; Podlipaev, Sergei A.; Maslov, Dmitri A. (2001-03-01). "Diversity and Phylogeny of Insect Trypanosomatids Based on Small Subunit rRNA Genes: Polyphyly of Leptomonas and Blastocrithidia". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 48 (2): 161–169. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2001.tb00298.x. PMID 12095103. S2CID 13880469.

- ^ Docampo R, de Souza W, Miranda K, Rohloff P, Moreno SN (March 2005). "Acidocalcisomes — conserved from bacteria to man". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 3 (3): 251–61. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1097. PMID 15738951. S2CID 31935658.

- ^ "GTDB - Tree at g__Kinetoplastibacterium". gtdb.ecogenomic.org. Archived from the original on 2022-12-20. Retrieved 2022-12-20.

- ^ de Souza, W.; Motta, M. C. (1999). "Endosymbiosis in protozoa of the Trypanosomatidae family". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 173 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13477.x. PMID 10220875.

- Bütikofer P, Ruepp S, Boschung M, Roditi I (September 1997). "'GPEET' procyclin is the major surface protein of procyclic culture forms of Trypanosoma brucei brucei strain 427". Biochemical Journal. 326 (Pt 2): 415–23. doi:10.1042/bj3260415. PMC 1218686. PMID 9291113.

- Dean S, Marchetti R, Kirk K, Matthews KR (May 2009). "A surface transporter family conveys the trypanosome differentiation signal". Nature. 459 (7244): 213–7. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..213D. doi:10.1038/nature07997. PMC 2685892. PMID 19444208.

- Engstler M, Boshart M; Boshart (November 2004). "Cold shock and regulation of surface protein trafficking convey sensitization to inducers of stage differentiation in Trypanosoma brucei". Genes & Development. 18 (22): 2798–811. doi:10.1101/gad.323404. PMC 528899. PMID 15545633.

- Hofer A, Steverding D, Chabes A, Brun R, Thelander L (May 2001). "Trypanosoma brucei CTP synthetase: a target for the treatment of African sleeping sickness". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (11): 6412–6. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.6412H. doi:10.1073/pnas.111139498. PMC 33482. PMID 11353848.

- Janovy, J; Roberts, L.S. (2005). Foundations of Parasitology (7th ed.). New York NY: McGraw Hill. pp. 61–69.

- Legros D, Ollivier G, Gastellu-Etchegorry M, et al. (July 2002). "Treatment of human African trypanosomiasis—present situation and needs for research and development" (PDF). Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2 (7): 437–40. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00321-3. hdl:10144/18268. PMID 12127356. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-12-01.

- Matthews KR (January 2005). "The developmental cell biology of Trypanosoma brucei". Journal of Cell Science. 118 (Pt 2): 283–90. doi:10.1242/jcs.01649. PMC 2686837. PMID 15654017.

- Matthews KR, Gull K; Gull (June 1994). "Evidence for an interplay between cell cycle progression and the initiation of differentiation between life cycle forms of African trypanosomes". Journal of Cell Biology. 125 (5): 1147–56. doi:10.1083/jcb.125.5.1147. PMC 2120053. PMID 8195296.

- Morrison LJ, Marcello L, McCulloch R (December 2009). "Antigenic variation in the African trypanosome: molecular mechanisms and phenotypic complexity" (PDF). Cellular Microbiology. 11 (12): 1724–34. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01383.x. PMID 19751359. S2CID 26552797. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- Seed JR, Wenck MA; Wenck (June 2003). "Role of the long slender to short stumpy transition in the life cycle of the African trypanosomes". Kinetoplastid Biology and Disease. 2 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1475-9292-2-3. PMC 165594. PMID 12844365.

- Shadan S (May 2009). "Microbiology: Signals for change". Nature. 459 (7244): 175. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..175S. doi:10.1038/459175a. PMID 19444199.

- Sherwin T, Gull K; Gull (June 1989). "The cell division cycle of Trypanosoma brucei brucei: timing of event markers and cytoskeletal modulations". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 323 (1218): 573–88. Bibcode:1989RSPTB.323..573S. doi:10.1098/rstb.1989.0037. PMID 2568647.

- "African trypanosomiasis". World Health Organization. August 2006. Archived from the original on 2016-12-04. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- Woodcock, Harold Mellor (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 340–347. (online). A comprehensive survey of the organisms' natural history.

External links

[edit]- Trykipedia, Trypanosomatid specific ontologies

- Tree of Life: Trypanosomatida

- Taxonomy at BOLD Systems

- Taxonomy at Taxonomicon

- Open Tree Taxonomy

- ZipcodeZoo