Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Excavata

View on Wikipedia

| Excavates Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

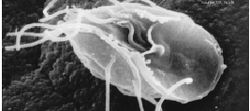

| Giardia lamblia, a parasitic diplomonad | |

| Scientific classification (obsolete as paraphyletic)

| |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| (unranked): | Excavata (Cavalier-Smith), 2002 |

| Groups included | |

|

See text | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

|

All of other Eukaryota | |

Excavata is an obsolete, extensive and diverse paraphyletic group of unicellular Eukaryota.[1][2] The group was first suggested by Simpson and Patterson in 1999[3][4] and the name latinized and assigned a rank by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 2002. It contains a variety of free-living and symbiotic protists, and includes some important parasites of humans such as Giardia and Trichomonas.[5] Excavates were formerly considered to be included in the now- obsolete Protista kingdom.[6] They were distinguished from other lineages based on electron-microscopic information about how the cells are arranged (they have a distinctive ultrastructural identity).[4] They are considered to be a basal flagellate lineage.[7]

On the basis of phylogenomic analyses, the group was shown to contain three widely separated eukaryote groups, the discobids, metamonads, and malawimonads.[8][9][10][11] A current view of the composition of the excavates is given below, indicating that the group is paraphyletic. Except for some Euglenozoa, all are non-photosynthetic.

Characteristics

[edit]Most excavates are unicellular, heterotrophic flagellates. Only some Euglenozoa are photosynthetic. In some (particularly anaerobic intestinal parasites), the mitochondria have been greatly reduced.[5] Some excavates lack "classical" mitochondria, and are called "amitochondriate", although most retain a mitochondrial organelle in greatly modified form (e.g. a hydrogenosome or mitosome). Among those with mitochondria, the mitochondrial cristae may be tubular, discoidal, or in some cases, laminar. Most excavates have two, four, or more flagella.[4] Many have a conspicuous ventral feeding groove with a characteristic ultrastructure, supported by microtubules—the "excavated" appearance of this groove giving the organisms their name.[3][6] However, various groups that lack these traits are considered to be derived excavates based on genetic evidence (primarily phylogenetic trees of molecular sequences).[6]

The Acrasidae slime molds are the only excavates to exhibit limited multicellularity. Like other cellular slime molds, they live most of their life as single cells, but will sometimes assemble into larger clusters.

Proposed group

[edit]

Excavate relationships were always uncertain, suggesting that they are not a monophyletic group.[12] Phylogenetic analyses often do not place malawimonads on the same branch as the other Excavata.[13]

Excavates were thought to include multiple groups:

| Taxon | Included taxa | Representative genera (examples) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discoba or JEH or Eozoa | Tsukubea | Tsukubamonas | |

| Euglenozoa | Euglena, Trypanosoma | Many important parasites, one large group with plastids (chloroplasts) | |

| Percolozoa | Naegleria, Acrasis | Most alternate between flagellate and amoeboid forms | |

| Jakobea | Jakoba, Reclinomonas | Free-living, sometimes loricate flagellates, with very gene-rich mitochondrial genomes | |

| Metamonada or POD | Preaxostyla | Trimastix, Paratrimastix | Amitochondriate flagellates, either free-living (Trimastix, Paratrimastix) or living in the hindguts of insects |

| Fornicata | Giardia, Carpediemonas | Amitochondriate, mostly symbiotes and parasites of animals. | |

| Parabasalia | Trichomonas, Cochlosoma | Amitochondriate flagellates, generally intestinal commensals of insects. Some human pathogens. | |

| Anaeramoebidae | Anaeramoeba | Anaerobic protists with hydrogenosomes instead of mitochondria. | |

| Malawimonada | Malawimonadea | Malawimonas, Imasa |

Discobids or JEH clade

[edit]Euglenozoa and Heterolobosea (Percolozoa) or Eozoa (as named by Cavalier-Smith[14]) appear to be particularly close relatives, and are united by the presence of discoid cristae within the mitochondria (superphylum Discicristata). A close relationship has been shown between Discicristata and Jakobida,[15] the latter having tubular cristae like most other protists, and hence were united under the taxon name Discoba, which was proposed for this supposedly monophyletic group.[1] This clade was defined as a node-based clade, receiving the definition "The least inclusive clade containing Jakoba libera (Ruinen, 1938) Patterson, 1990; Andalucia godoyi, Lara et al., 2006; Euglena gracilis Klebs 1883; and Naegleria gruberi (Schardinger, 1899) Alexeieff, 1912." Alternatively, the clade has been termed the jakobid, euglenozoan and heterolobosean group JEH.[16]

Metamonads

[edit]Metamonads are unusual in not having classical mitochondria—instead they have hydrogenosomes, mitosomes or uncharacterised organelles. The oxymonad Monocercomonoides is reported to have completely lost homologous organelles. There are competing explanations.[17][18]

Malawimonads

[edit]The malawimonads have been proposed to be members of Excavata owing to their typical excavate morphology, and phylogenetic affinity to other excavate groups in some molecular phylogenies. However, their position among eukaryotes remains elusive.[2]

Ancyromonads

[edit]Ancyromonads are small free-living cells with a narrow longitudinal groove down one side of the cell. The ancyromonad groove is not used for "suspension feeding", unlike in "typical excavates" (e.g. malawimonads, jakobids, Trimastix, Carpediemonas, Kiperferlia, etc). Ancyromonads instead capture prokaryotes attached to surfaces. The phylogenetic placement of ancyromonads is poorly understood (in 2020), however some phylogenetic analyses place them as close relatives of malawimonads.[9]

Evolution

[edit]Origin of the eukaryotes

[edit]The conventional explanation for the origin of the eukaryotes is that a heimdallarchaeian or another Archaea acquired an alphaproteobacterium[19] as an endosymbiont, and that this became the mitochondrion, the organelle providing oxidative respiration to the eukaryotic cell.[20]

Caesar al Jewari and Sandra Baldauf argue instead that the eukaryotes possibly started with an endosymbiosis event of a Deltaproteobacterium or Gammaproteobacterium, accounting for the otherwise unexplained presence of anaerobic bacterial enzymes in Metamonada. The sister of the Preaxostyla within Metamonada represents the rest of the eukaryotes which acquired an Alphaproteobacterium. In their scenario, the hydrogenosome and mitosome, both conventionally considered "mitochondrion-derived organelles", would predate the mitochondrion, and instead be derived from the earlier symbiotic bacterium.[18]

Phylogeny

[edit]In 2023, using molecular phylogenetic analysis of 186 taxa, Al Jewari and Baldauf proposed a phylogenetic tree with the metamonad Parabasalia as basal eukaryotes. Discoba and the rest of the Eukaryota appear to have emerged as sister taxon to the Preaxostyla, incorporating a single alphaproteobacterium as mitochondria by endosymbiosis. Thus the Fornicata are more closely related to e.g. animals than to Parabasalia. The rest of the eukaryotes emerged within the Excavata as sister of the Discoba; as they are within the same clade but are not cladistically considered part of the Excavata yet, the Excavata in this analysis is highly paraphyletic.[18]

|

"Excavata" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Anaeramoeba are associated with Parabasalia, but could turn out to be more basal as the root of a tree is often difficult to pinpoint.[21]

See also

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

Trypanosoma brucei (Euglenozoa: Kinetoplastida)

-

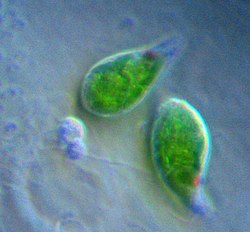

Bodo sp. (Euglenozoa: Kinetoplastida)

-

Percolomonas sp. (Percolozoa)

-

Stephanopogon sp. (Percolozoa)

-

Acrasis rosea (Percolozoa: Heterolobosea)

-

Jakobids (Jakobida)

-

Giardia sp. (Metamonada: Fornicata: Diplomonadida)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Hampl, Vladimir; Hug, Laura; Leigh, Jessica W.; et al. (2009). "Phylogenomic analyses support the monophyly of Excavata and resolve relationships among eukaryotic "supergroups"". PNAS. 106 (10): 3859–3864. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.3859H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807880106. PMC 2656170. PMID 19237557.

- ^ a b Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Inagaki, Yuji; Roger, Andrew J. (2006). "Comprehensive multigene phylogenies of excavate protists reveal the evolutionary positions of "primitive" eukaryotes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (3): 615–625. doi:10.1093/molbev/msj068. PMID 16308337.

- ^ a b Simpson, Alastair G.B.; Patterson, David J. (December 1999). "The ultrastructure of Carpediemonas membranifera (Eukaryota) with reference to the 'excavate hypothesis'". European Journal of Protistology. 35 (4): 353–370. doi:10.1016/S0932-4739(99)80044-3.

- ^ a b c Simpson, Alastair G. B. (November 2003). "Cytoskeletal organization, phylogenetic affinities and systematics in the contentious taxon Excavata (Eukaryota)". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (6): 1759–1777. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02578-0. PMID 14657103.

- ^ a b Dawkins, Richard; Wong, Yan (2016). The Ancestor's Tale. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-544-85993-7.

- ^ a b c Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2002). "The phagotrophic origin of eukaryotes and phylogenetic classification of Protozoa". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 52 (2): 297–354. doi:10.1099/00207713-52-2-297. PMID 11931142.

- ^ Dawson, Scott C.; Paredez, Alexander R. (2013). "Alternative cytoskeletal landscapes: cytoskeletal novelty and evolution in basal excavate protists". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 25 (1): 134–141. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2012.11.005. PMC 4927265. PMID 23312067.

- ^ Burki, Fabien; Roger, Andrew J.; Brown, Matthew W.; et al. (January 2020). "The New Tree of Eukaryotes". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 35 (1): 43–55. Bibcode:2020TEcoE..35...43B. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.008. PMID 31606140. S2CID 204545629.

- ^ a b Brown, Matthew W.; Heiss, Aaron A.; Kamikawa, Ryoma; et al. (2018-01-19). "Phylogenomics Places Orphan Protistan Lineages in a Novel Eukaryotic Super-Group". Genome Biology and Evolution. 10 (2): 427–433. doi:10.1093/gbe/evy014. PMC 5793813. PMID 29360967.

- ^ Heiss, Aaron A.; Kolisko, Martin; Ekelund, Fleming; et al. (4 April 2018). "Combined morphological and phylogenomic re-examination of malawimonads, a critical taxon for inferring the evolutionary history of eukaryotes". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (4) 171707. Bibcode:2018RSOS....571707H. doi:10.1098/rsos.171707. PMC 5936906. PMID 29765641.

- ^ Keeling, Patrick J.; Burki, Fabien (19 August 2019). "Progress towards the Tree of Eukaryotes". Current Biology. 29 (16): R808 – R817. Bibcode:2019CBio...29.R808K. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.07.031. PMID 31430481.

- ^ Laura Wegener Parfrey; Erika Barbero; Elyse Lasser; Micah Dunthorn; Debashish Bhattacharya; David J Patterson; Laura A Katz (December 2006). "Evaluating support for the current classification of eukaryotic diversity". PLOS Genetics. 2 (12): e220. doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PGEN.0020220. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 1713255. PMID 17194223. Wikidata Q21090155.

- ^ Tice, Alexander K.; Žihala, David; Pánek, Tomáš; et al. (2021). "PhyloFisher: A phylogenomic package for resolving eukaryotic relationships". PLOS Biology. 19 (8) e3001365. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001365. PMC 8345874. PMID 34358228.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (23 December 2009). "Kingdoms Protozoa and Chromista and the eozoan root of the eukaryotic tree". Biology Letters. 6 (3). The Royal Society: 342–345. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0948. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 2880060. PMID 20031978.

- ^ Rodríguez-Ezpeleta, Naiara; Brinkmann, Henner; Burger, Gertraud; et al. (2007). "Toward Resolving the Eukaryotic Tree: The Phylogenetic Positions of Jakobids and Cercozoans". Current Biology. 17 (16): 1420–1425. Bibcode:2007CBio...17.1420R. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.036. PMID 17689961.

- ^ Rodríguez-Ezpeleta N, Brinkmann H, Burger G, Roger AJ, Gray MW, Philippe H, Franz Lang B (2007). "Toward Resolving the Eukaryotic Tree: The Phylogenetic Positions of Jakobids and Cercozoans". Current Biology. 17 (16): 1420–1425. Bibcode:2007CBio...17.1420R. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.036. PMID 17689961.

- ^ Bui, Elisabeth T.; Bradley, Peter J.; Johnson, Patricia J. (3 September 1996). "A common evolutionary origin for mitochondria and hydrogenosomes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 93 (18): 9651–9656. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.9651B. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.18.9651. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 38483. PMID 8790385.

- ^ a b c Al Jewari, Caesar; Baldauf, Sandra L. (2023-04-28). "An excavate root for the eukaryote tree of life". Science Advances. 9 (17) eade4973. Bibcode:2023SciA....9E4973A. doi:10.1126/sciadv.ade4973. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 10146883. PMID 37115919.

- ^ Tria, F.D.K.; Brueckner, J.; Skejo, J.; Xavier, J.C.; Kapust, N.; Knopp, M.; et al. (7 May 2021). "Gene Duplications Trace Mitochondria to the Onset of Eukaryote Complexity". Genome Biology and Evolution. 13 (5). doi:10.1093/gbe/evab055. PMC 8175051. PMID 33739376.

- ^ a b Eme, Laura; Tamarit, Daniel; Caceres, Eva F.; et al. (2023-03-09). "Inference and reconstruction of the heimdallarchaeial ancestry of eukaryotes". Nature. 618 (7967): 992–999. Bibcode:2023Natur.618..992E. bioRxiv 10.1101/2023.03.07.531504. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06186-2. PMC 10307638. PMID 37316666.

- ^ Stairs, Courtney W.; Táborský, Petr; Salomaki, Eric D.; et al. (December 2021). "Anaeramoebae are a divergent lineage of eukaryotes that shed light on the transition from anaerobic mitochondria to hydrogenosomes". Current Biology. 31 (24): 5605–5612.e5. Bibcode:2021CBio...31E5605S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.10.010. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 34710348. S2CID 240054026.