Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Euglenozoa

View on Wikipedia

| Euglenozoa Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

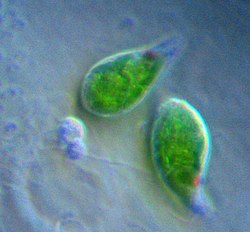

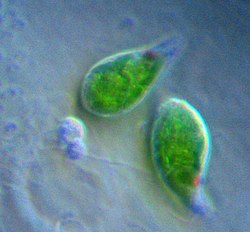

| Two Euglena | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Discoba |

| Clade: | Discicristata |

| Phylum: | Euglenozoa Cavalier-Smith, 1981[2] |

| Classes | |

| |

Euglenozoa are a large group of flagellate Discoba. They include a variety of common free-living species, as well as a few important parasites, some of which infect humans. Euglenozoa are represented by four major groups, i.e., Kinetoplastea, Diplonemea, Euglenida, and Symbiontida. Euglenozoa are unicellular, mostly around 15–40 μm (0.00059–0.00157 in) in size, although some euglenids get up to 500 μm (0.020 in) long.[4]

Structure

[edit]Most euglenozoa have two flagella, which are inserted parallel to one another in an apical or subapical pocket. In some these are associated with a cytostome or mouth, used to ingest bacteria or other small organisms. This is supported by one of three sets of microtubules that arise from the flagellar bases; the other two support the dorsal and ventral surfaces of the cell.[5]

Some other euglenozoa feed through absorption, and many euglenids possess chloroplasts, the only eukaryotes outside Diaphoretickes to do so without performing kleptoplasty,[6][7] and so obtain energy through photosynthesis. These chloroplasts are surrounded by three membranes and contain chlorophylls A and B, along with other pigments, so are probably derived from a green alga, captured long ago in an endosymbiosis by a basal euglenozoan. Reproduction occurs exclusively through cell division. During mitosis, the nuclear membrane remains intact, and the spindle microtubules form inside of it.[5]

The group is characterized by the ultrastructure of the flagella. In addition to the normal supporting microtubules or axoneme, each contains a rod (called paraxonemal), which has a tubular structure in one flagellum and a latticed structure in the other. Based on this, two smaller groups have been included here: the diplonemids and Postgaardi.[8]

Classification

[edit]Historically, euglenozoans have been treated as either plants or animals, depending on whether they belong to largely photosynthetic groups or not. Hence they have names based on either the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICNafp) or the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). For example, one family has the name Euglenaceae under the ICNafp and the name Euglenidae under the ICZN. As another example, the genus name Dinema is acceptable under the ICZN, but illegitimate under the ICNafp, as it is a later homonym of an orchid genus, so that the synonym Dinematomonas must be used instead.[9]

The Euglenozoa are generally accepted as monophyletic. They are related to Percolozoa; the two share mitochondria with disk-shaped cristae, which only occurs in a few other groups.[10] Both probably belong to a larger group of eukaryotes called the Excavata.[11] This grouping, though, has been challenged.[12]

Phylogeny

[edit]The phylogeny based on the work of Cavalier-Smith (2016):[13]

| Euglenozoa phylogeny – Cavalier-Smith (2016) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A consensus phylogeny following the review by Kostygov et al. (2021):[9]

| Euglenozoa phylogeny – Kostygov et al. (2021) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Taxonomy

[edit]Cavalier-Smith (2016/2017)

[edit]The following classification of Euglenozoa is as described by Cavalier-Smith in 2016,[13] modified to include the new subphylum Plicomonada according to Cavalier-Smith et al (2017).[14]

Phylum Euglenozoa Cavalier-Smith 1981 emend. Simpson 1997 [Euglenobionta]

- Subphylum Glycomonada Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Class Diplonemea Cavalier-Smith 1993 emend. Simpson 1997 [Diplosonematea; Diplonemia Cavalier-Smith 1993]

- Order Diplonemida Cavalier-Smith 1993 [Hemistasiida]

- Family Hemistasiidae Cavalier-Smith 2016 [Entomosigmaceae]

- Family Diplonemidae Cavalier-Smith 1993 [Rhynchopodaceae Skuja 1948 ex Cavalier-Smith 1993]

- Order Diplonemida Cavalier-Smith 1993 [Hemistasiida]

- Class Kinetoplastea Honigberg 1963 emend. Margulis 1974 [Kinetoplastida Honigberg 1963; Kinetoplasta Honigberg 1963 stat. nov.]

- Subclass Prokinetoplastina Vickerman 2004

- Order Prokinetoplastida Vickerman 2004

- Family Ichthyobodonidae Isaksen et al., 2007

- Order Prokinetoplastida Vickerman 2004

- Subclass Metakinetoplastina Vickerman 2004

- Order Bodonida* Hollande 1952 em. Vickerman 1976, Kryov et al. 1980

- Suborder Neobodonida Vickerman 2004

- Family Rhynchomonadidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Family Neobodonidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Suborder Parabodonida Vickerman 2004

- Family Parabodonidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Family Cryptobiidae* Vickerman 2004

- Suborder Eubodonida Vickerman 2004

- Family Bodonidae Bütschli 1883 [Bodonaceae Lemmermann 1914; Bodoninae Bütschli 1883; Pleuromonadidae Kent 1880]

- Suborder Neobodonida Vickerman 2004

- Order Trypanosomatida Kent 1880 stat. n. Hollande, 1952 emend. Vickerman 2004

- Family Trypanosomatidae Doflein 1901

- Order Bodonida* Hollande 1952 em. Vickerman 1976, Kryov et al. 1980

- Subclass Prokinetoplastina Vickerman 2004

- Class Diplonemea Cavalier-Smith 1993 emend. Simpson 1997 [Diplosonematea; Diplonemia Cavalier-Smith 1993]

- Subphylum Plicomonada Cavalier-Smith 2017

- Infraphylum Postgaardia Cavalier-Smith 2016 stat. nov. Cavalier-Smith 2017

- Class Postgaardea Cavalier-Smith 1998 s.s. [Symbiontida Yubuki et al., 2009]

- Order Bihospitida Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Family Bihospitidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Postgaardida Cavalier-Smith 2003

- Family Calkinsiidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Family Postgaardidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Bihospitida Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Class Postgaardea Cavalier-Smith 1998 s.s. [Symbiontida Yubuki et al., 2009]

- Infraphylum Euglenoida Bütschli 1884 emend. Senn 1900 stat. nov. Cavalier-Smith, 2017 [Euglenophyta; Euglenida Buetschli 1884; Euglenoidina Buetschli 1884]

- Parvphylum Entosiphona Cavalier-Smith 2016 stat. nov. Cavalier-Smith 2017

- Class Entosiphonea Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Entosiphonida Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Family Entosiphonidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Entosiphonida Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Class Entosiphonea Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Parvphylum Dipilida Cavalier-Smith 2016 stat. nov. Cavalier-Smith 2017

- Superclass Rigimonada* Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Class Stavomonadea Cavalier-Smith 2016 [Petalomonadea Cavalier-Smith 1993; Petalomonadophyceae]

- Subclass Heterostavia Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Heterostavida Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Family Serpenomonadidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Heterostavida Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Subclass Homostavia Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Decastavida Cavalier-Smith 2016a

- Family Decastavidae Cavalier-Smith 2016a

- Family Keelungiidae Cavalier-Smith 2016a

- Order Petalomonadida Cavalier-Smith 1993 [Sphenomonadales Leedale 1967; Sphenomonadina Leedale 1967]

- Family Sphenomonadidae Kent 1880

- Family Petalomonadidae [Petalomonadaceae Buetschli 1884; Notosolenaceae Stokes 1888; Scytomonadaceae Ritter von Stein 1878]

- Order Decastavida Cavalier-Smith 2016a

- Subclass Heterostavia Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Class Ploeotarea Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Ploeotiida Cavalier-Smith 1993

- Family Lentomonadidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Family Ploeotiidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Ploeotiida Cavalier-Smith 1993

- Class Stavomonadea Cavalier-Smith 2016 [Petalomonadea Cavalier-Smith 1993; Petalomonadophyceae]

- Superclass Spirocuta Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Class Peranemea Cavalier-Smith 1993 emend. Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Subclass Acroglissia Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Acroglissida Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Family Teloproctidae Cavalier-Smith 2016a

- Order Acroglissida Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Subclass Peranemia Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Peranemida Bütschli 1884 stat. nov. Cavalier-Smith 1993

- Family Peranematidae [Peranemataceae Dujardin 1841; Pseudoperanemataceae Christen 1962]

- Order Peranemida Bütschli 1884 stat. nov. Cavalier-Smith 1993

- Subclass Anisonemia Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Anisonemida Cavalier-Smith 2016 [Heteronematales Leedale 1967]

- Family Anisonemidae Saville Kent, 1880 em. Cavalier-Smith 2016 [Heteronemidae Calkins 1926; Zygoselmidaceae Kent 188]

- Order Natomonadida Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Suborder Metanemina Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Family Neometanemidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Suborder Rhabdomonadina Leedale 1967 emend. Cavalier-Smith 1993 [Astasida Ehrenberg 1831; Rhabdomonadia Cavalier-Smith 1993; Rhabdomonadophyceae; Rhabdomonadales]

- Family Distigmidae Hollande, 1942

- Family Astasiidae Saville Kent, 1884 [Astasiaceae Ehrenberg orth. mut. Senn 1900; Rhabdomonadaceae Fott 1971; Menoidiaceae Buetschli 188; Menoidiidae Hollande, 1942]

- Suborder Metanemina Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Anisonemida Cavalier-Smith 2016 [Heteronematales Leedale 1967]

- Subclass Acroglissia Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Class Euglenophyceae Schoenichen 1925 emend. Marin & Melkonian 2003 [Euglenea Bütschli 1884 emend. Busse & Preisfeld 2002; Euglenoidea Bütschli 1884; Euglenida Bütschli 1884] (Photosynthetic clade)

- Subclass Rapazia Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Subclass Euglenophycidae Busse and Preisfeld, 2003

- Order Eutreptiida [Eutreptiales Leedale 1967 emend. Marin & Melkonian 2003; Eutreptiina Leedale 1967]

- Family Eutreptiaceae [Eutreptiaceae Hollande 1942]

- Order Euglenida Ritter von Stein, 1878 stat. n. Calkins, 1926 [Euglenales Engler 1898 emend. Marin & Melkonian 2003; Euglenina Buetschli 1884; Euglenomorphales Leedale 1967; Colaciales Smith 1938]

- Family Euglenamorphidae Hollande, 1952 stat. n. Cavalier-Smith 2016 [Euglenomorphaceae; Hegneriaceae Brumpt & Lavier 1924]

- Family Phacidae [Phacaceae Kim et al. 2010]

- Family Euglenidae Bütschli 1884 [Euglenaceae Dujardin 1841 emend. Kim et al. 2010; Colaciaceae Smith 1933] (Mucilaginous clade)

- Order Eutreptiida [Eutreptiales Leedale 1967 emend. Marin & Melkonian 2003; Eutreptiina Leedale 1967]

- Class Peranemea Cavalier-Smith 1993 emend. Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Superclass Rigimonada* Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Parvphylum Entosiphona Cavalier-Smith 2016 stat. nov. Cavalier-Smith 2017

- Infraphylum Postgaardia Cavalier-Smith 2016 stat. nov. Cavalier-Smith 2017

Kostygov et al. (2021)

[edit]Phylum Euglenozoa Cavalier-Smith 1981 emend. Simpson 1997[9]

- Class Kinetoplastea Honigberg, 1963 emend. Vickerman, 1976

- Subclass Prokinetoplastia Vickerman, 2004

- Order Prokinetoplastida Vickerman, 2004

- Family Ichthyobodonidae Isaksen et al., 2007

- Family Perkinselidae Kostygov, 2021

- Order Prokinetoplastida Vickerman, 2004

- Subclass Metakinetoplastia Vickerman, 2004

- Order Eubodonida Vickerman 2004

- Family Bodonidae Bütschli, 1883

- Order Neobodonida Vickerman, 2004

- Family Allobodonidae Goodwin et al., 2018

- Family Neobodonidae Cavalier-Smith, 2016

- Family Rhynchomonadinae Cavalier-Smith, 2016

- Order Parabodonida Vickerman, 2004

- Family Cryptobiidae Poche, 1911 emend. Kostygov, 2021

- Family Trypanoplasmatidae Hartmann and Chagas, 1910 emend. Kostygov, 2021

- Order Trypanosomatida Kent, 1880

- Family Trypanosomatidae Doflein, 1901

- Order Eubodonida Vickerman 2004

- Subclass Prokinetoplastia Vickerman, 2004

- Class Diplonemea Cavalier-Smith, 1993

- Order Diplonemida Cavalier-Smith, 1993

- Family Diplonemidae Cavalier-Smith, 1993

- Family Hemistasiidae Cavalier-Smith, 2016

- Family Eupelagonemidae Okamoto and Keeling, 2019

- Order Diplonemida Cavalier-Smith, 1993

- Class Euglenida Bütschli, 1884 emend. Simpson, 1997

- Clade Olkaspira Lax and Simpson, 2020

- Clade Spirocuta Cavalier-Smith, 2016

- Clade Euglenophyceae Schoenichen, 1925 emend. Marin and Melkonian, 2003

- Order Euglenales Leedale, 1967 emend. Marin and Melkonian, 2003

- Family Euglenaceae Dujardin, 1841 emend. Kim et al., 2010 [Euglenidae Dujardin, 1841]

- Family Phacaceae Kim, Triemer and Shin 2010 [Phacidae Kim, Triemer and Shin 2010]

- Order Eutreptiales Leedale, 1967 emend. Marin and Melkonian, 2003

- Family Eutreptiaceae Hollande, 1942 [Eutreptiidae Hollande, 1942]

- Order Rapazida Cavalier-Smith, 2016

- Family Rapazidae Cavalier-Smith, 2016

- Order Euglenales Leedale, 1967 emend. Marin and Melkonian, 2003

- Clade Anisonemia Cavalier-Smith, 2016

- Order Anisonemida Cavalier-Smith, 2016

- Family Anisonemidae Kent, 1880

- Clade Aphagea Cavalier-Smith, 1993 emend. Busse and Preisfeld, 2002

- Order Anisonemida Cavalier-Smith, 2016

- Order Peranemida Cavalier-Smith, 1993

- Clade Euglenophyceae Schoenichen, 1925 emend. Marin and Melkonian, 2003

- Clade Spirocuta Cavalier-Smith, 2016

- Clade Alistosa Lax et al., 2020

- Order Petalomonadida Cavalier-Smith, 1993

- Clade Olkaspira Lax and Simpson, 2020

- Class Symbiontida Yubuki, Edgcomb, Bernhard and Leander, 2009

References

[edit]- ^ Zakryś, B; Milanowski, R; Karnkowska, Anna (2017). "Evolutionary Origin of Euglena". Euglena: Biochemistry, Cell and Molecular Biology. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 979. pp. 3–17. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-54910-1_1. ISBN 978-3-319-54908-8. PMID 28429314.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (1981). "Eukaryote kingdoms: seven or nine?". Bio Systems. 14 (3–4): 461–481. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(81)90050-2. PMID 7337818.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (October 2017). "Euglenoid pellicle morphogenesis and evolution in light of comparative ultrastructure and trypanosomatid biology: Semi-conservative microtubule/strip duplication, strip shaping and transformation". European Journal of Protistology. 61 (Pt A): 137–179. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2017.09.002. PMID 29073503.

- ^ "Euglenozoa". Encyclopedia of Life. National Museum of Natural History - Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ a b Patterson DJ (October 1999). "The Diversity of Eukaryotes". The American Naturalist. 154 (S4): S96 – S124. doi:10.1086/303287. PMID 10527921. S2CID 4367158.

- ^ Burki, Fabien; Roger, Andrew J.; Brown, Matthew W.; Simpson, Alastair G.B. (2020-01-01). "The New Tree of Eukaryotes". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 35 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.008. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 31606140.

- ^ Sibbald, Shannon J.; Archibald, John M. (2020-05-20). "Genomic Insights into Plastid Evolution". Genome Biology and Evolution. 12 (7): 978–990. doi:10.1093/gbe/evaa096. PMC 7348690. PMID 32402068.

- ^ Simpson AG (1997). "The Identity and Composition of Euglenozoa". Archiv für Protistenkunde. 148 (3): 318–328. doi:10.1016/s0003-9365(97)80012-7.

- ^ a b c Kostygov AY, Karnkowska A, Votýpka J, Tashyreva D, Maciszewski K, Yurchenko V, Lukeš J (March 2021). "Euglenozoa: taxonomy, diversity and ecology, symbioses and viruses". Open Biology. 11 (3) 200407. doi:10.1098/rsob.200407. PMC 8061765. PMID 33715388.

- ^ Baldauf SL, Roger AJ, Wenk-Siefert I, Doolittle WF (November 2000). "A kingdom-level phylogeny of eukaryotes based on combined protein data". Science. 290 (5493): 972–977. Bibcode:2000Sci...290..972B. doi:10.1126/science.290.5493.972. PMID 11062127.

- ^ Simpson AG (November 2003). "Cytoskeletal organization, phylogenetic affinities and systematics in the contentious taxon Excavata (Eukaryota)". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (Pt 6): 1759–1777. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02578-0. PMID 14657103.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (June 2010). "Kingdoms Protozoa and Chromista and the eozoan root of the eukaryotic tree". Biology Letters. 6 (3): 342–345. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0948. PMC 2880060. PMID 20031978.

- ^ a b Cavalier-Smith T (October 2016). "Higher classification and phylogeny of Euglenozoa". European Journal of Protistology. 56: 250–276. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2016.09.003. PMID 27889663.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (October 2017). "Euglenoid pellicle morphogenesis and evolution in light of comparative ultrastructure and trypanosomatid biology: Semi-conservative microtubule/strip duplication, strip shaping and transformation". European Journal of Protistology. 61 (Pt A): 137–179. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2017.09.002. PMID 29073503.