Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

QRS complex

View on Wikipedia

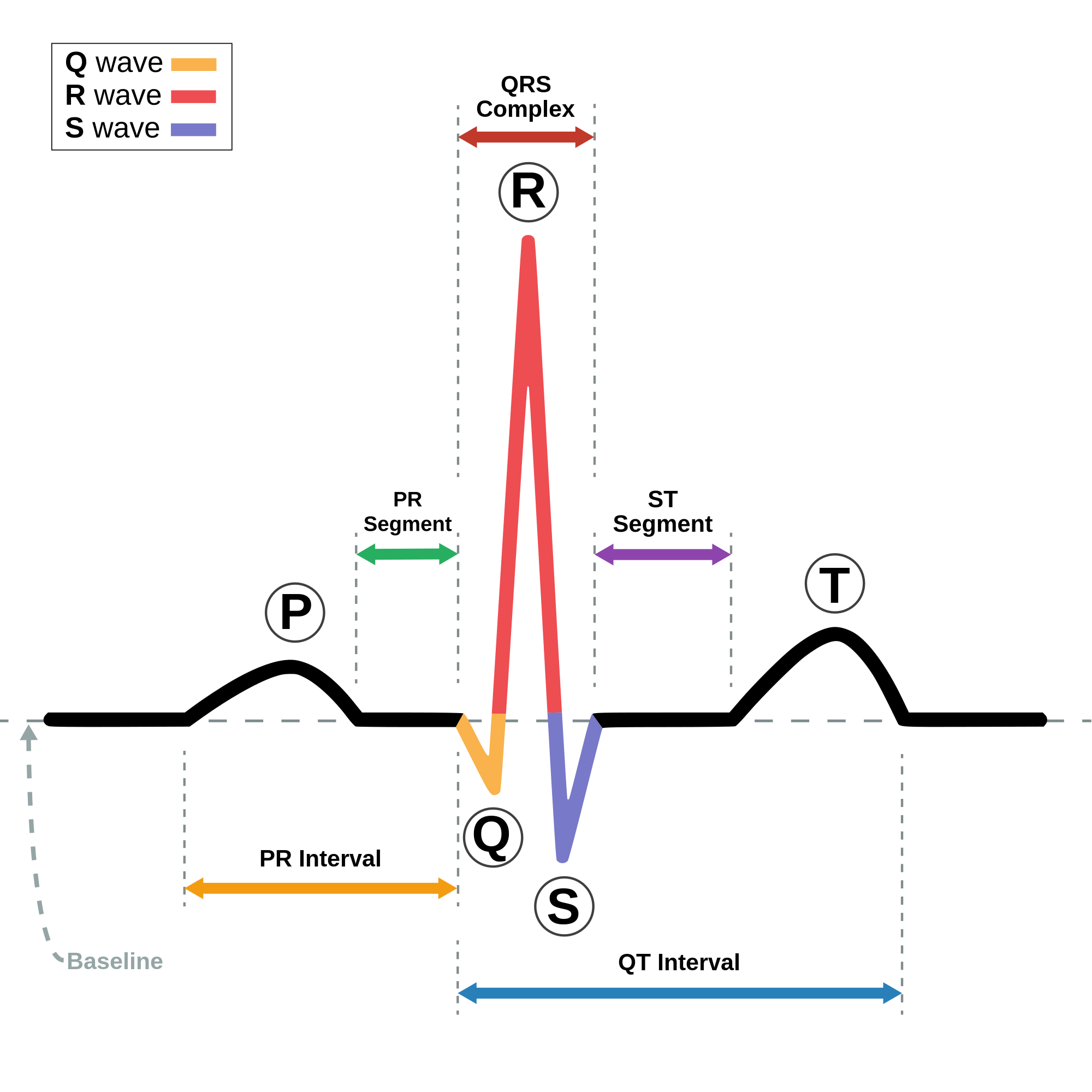

The QRS complex is the combination of three of the graphical deflections seen on a typical electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). It is usually the central and most visually obvious part of the tracing. It corresponds to the depolarization of the right and left ventricles of the heart and contraction of the large ventricular muscles.

In adults, the QRS complex normally lasts 80 to 100 ms; in children it may be shorter. The Q, R, and S waves occur in rapid succession, do not all appear in all leads, and reflect a single event and thus are usually considered together. A Q wave is any downward deflection immediately following the P wave. An R wave follows as an upward deflection, and the S wave is any downward deflection after the R wave. The T wave follows the S wave, and in some cases, an additional U wave follows the T wave.

To measure the QRS interval start at the end of the PR interval (or beginning of the Q wave) to the end of the S wave. Normally this interval is 0.08 to 0.10 seconds. When the duration is longer it is considered a wide QRS complex.

Formation

[edit]Depolarization of the heart ventricles occurs almost simultaneously, via the bundle of His and Purkinje fibers. If they are working efficiently, the QRS complex duration in adults is 80 to 110 ms.[citation needed]

Clinical significance

[edit]Any abnormality of conduction takes longer and causes "widened" QRS complexes, sometimes called cardiac aberrancy. In bundle branch block, there can be an abnormal second upward deflection within the QRS complex. In this case, such a second upward deflection is referred to as R′ (pronounced "R prime"). This would be described as an RSR′ pattern.

Ventricles contain more muscle mass than the atria. Therefore, the QRS complex is considerably larger than the P wave. The QRS complex is often used to determine the axis of the electrocardiogram, although it is also possible to determine a separate P wave axis.

The duration, amplitude, and morphology of the QRS complex are useful in diagnosing cardiac arrhythmias, conduction abnormalities, ventricular hypertrophy, myocardial infarction, electrolyte derangements, and other disease states.

High frequency analysis of the QRS complex may be useful for detection of coronary artery disease during an exercise stress test.[1]

Components

[edit]

| Parameter | Normal value | Value comments | Clinical significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| QRS duration | 75 to 105 ms[2] | Shorter in children[3] | Prolonged duration could indicate hyperkalemia[4] or intraventricular conduction delay such as bundle branch block. |

| QRS amplitude |

|

Increased amplitude indicates cardiac hypertrophy | |

| Ventricular activation time (VAT) |

Measured in increased QRS amplitude[3] | ||

| Q wave | Abnormality indicates presence of infarction[5] | ||

| R wave | Large amplitude might indicate of left ventricular hypertrophy[7]

Duration longer than 45 ms might indicate left posterior fascicular block, LVH or LBBB.[8] | ||

| S wave | Large amplitude might indicate of left ventricular hypertrophy[9] |

Q wave

[edit]Normal Q waves, when present, represent depolarization of the interventricular septum. For this reason, they are referred to as septal Q waves and can be appreciated in the lateral leads I, aVL, V5 and V6.

Pathologic Q waves occur when the electrical signal passes through stunned or scarred heart muscle; as such, they are usually markers of previous myocardial infarctions, with subsequent fibrosis. A pathologic Q wave is defined as having a deflection amplitude of 25% or more of the subsequent R wave, or being > 0.04 s (40 ms) in width and > 2 mm in amplitude. However, diagnosis requires the presence of this pattern in more than one corresponding lead.

R wave progression

[edit]Looking at the precordial leads, the R wave usually progresses from showing an rS-type complex in V1 with an increasing R and a decreasing S wave when moving toward the left side. There is usually a qR-type of complex in V5 and V6, with the R-wave amplitude usually taller in V5 than in V6. It is normal to have a narrow QS and rSr' patterns in V1, and this is also the case for qRs and R patterns in V5 and V6. The transition zone is where the QRS complex changes from predominantly negative to predominantly positive (R/S ratio becoming >1), and this usually occurs at V3 or V4. It is normal to have the transition zone at V2 (called "early transition") and at V5 (called "delayed transition").[10] In biomedical engineering, the maximum amplitude in the R wave is usually called "R peak amplitude", or just "R peak".[11][12] Accurate R peak detection is essential in signal processing equipment for heart rate measurement and it is the main feature used for arrhythmia detection.[13][14]

The definition of poor R wave progression (PRWP) varies in the literature. It may be defined, for example, as R wave of less than 2–4 mm in leads V3 or V4 and/or presence of a reversed R wave progression, which is defined as R in V4 < R in V3 or R in V3 < R in V2 or R in V2 < R in V1, or any combination of these.[10] Poor R wave progression is commonly attributed to anterior myocardial infarction, but it may also be caused by left bundle branch block, Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, right and left ventricular hypertrophy, or a faulty ECG recording technique.[10]

R wave peak time

[edit]R wave peak time (RWPT) represents the time from the onset of QRS complex to the peak of R wave, which is usually measured in aVL and V5 or V6 leads.[15]

R-peak time for right ventricle is measured from leads V1 or V2, where upper range of normal is 35 ms. R wave peak time for left ventricle is measured from lead V5 or V6 and 45 ms is the upper range of normal.[6] R wave peak time is considered to be prolonged if it's more than 45 ms.

J-point

[edit]The point where the QRS complex meets the ST segment is the J-point. The J-point is easy to identify when the ST segment is horizontal and forms a sharp angle with the last part of the QRS complex. However, when the ST segment is sloped or the QRS complex is wide, the two features do not form a sharp angle and the location of the J-point is less clear. There is no consensus on the precise location of the J-point in these circumstances.[16] Two possible definitions are:

Terminology

[edit]

Not every QRS complex contains a Q wave, an R wave, and an S wave. By convention, any combination of these waves can be referred to as a QRS complex. However, correct interpretation of difficult ECGs requires exact labeling of the various waves. Some authors use lowercase and capital letters, depending on the relative size of each wave. For example, an Rs complex would be positively deflected, while an rS complex would be negatively deflected. If both complexes were labeled RS, it would be impossible to appreciate this distinction without viewing the actual ECG.

Monomorphic or polymorphic

[edit]Monomorphic refers to all QRS waves in a single lead being similar in shape. Polymorphic means that the QRS change from complex to complex.[18] These terms are used in the description of ventricular tachycardia.

Algorithms

[edit]A common algorithm used for QRS complex detection is the Pan-Tompkins[19] algorithm (or method); another is based on the Hilbert transform.[20][21][22][23] Numerous other algorithms have been proposed and investigated.[24] In recent research, heart beat detection methods based on visibility graphs have been introduced, enabling fast and sample-precise R-peak annotation even in noisy ECG.[25][26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Fletcher GF, Ades PA, Kligfield P, Arena R, Balady GJ, Bittner VA, et al. (August 2013). "Exercise standards for testing and training: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association". Circulation. 128 (8): 873–934. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829b5b44. PMID 23877260.

- ^ Yanowitz FG. "III. Characteristics of the Normal ECG". University of Utah School of Medicine. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Compendium for interpretation of ECG at Uppsala Institution for Clinical Physiology. Year 2010

- ^ "Complementary and Alternative Medicine Index (CAM)". Archived from the original on 4 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. > EKG Interpretive skills Retrieved on April 22, 2010

- ^ a b c Pérez-Riera AR, de Abreu LC, Barbosa-Barros R, Nikus KC, Baranchuk A (January 2016). "R-Peak Time: An Electrocardiographic Parameter with Multiple Clinical Applications". Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology. 21 (1): 10–19. doi:10.1111/anec.12323. PMC 6931847. PMID 26523751.

- ^ Burns E, Buttner R (2018-08-01). "Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (LVH)". Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL. Retrieved 2022-01-17.

- ^ Cadogan M, Buttner R (2020-10-01). "R Wave Peak Time RWPT". Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL. Retrieved 2022-01-17.

- ^ Burns E, Buttner R (2018-08-01). "Left Ventricular Hypertrophy (LVH)". Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL. Retrieved 2022-01-17.

- ^ a b c MacKenzie R (2005). "Poor R-wave progression". Journal of Insurance Medicine. 37 (1): 58–62. PMID 15895699.

- ^ Szczepaniak PS, Lisboa PJ, Kacprzyk J (2000). Fuzzy Systems in Medicine. Springer. p. 256. ISBN 978-3-7908-1263-3.

- ^ Gacek A, Pedrycz W (2011). ECG Signal Processing, Classification and Interpretation: A Comprehensive Framework of Computational Intelligence. Springer. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-85729-867-6.

- ^ Pise SJ (2011). ThinkQuest 2010: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Contours of Computing Technology. Springer. p. 8. ISBN 978-81-8489-988-7.

- ^ Yoo HJ, van Hoof C (2010). Bio-Medical CMOS ICs. Springer. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-4419-6596-7.

- ^ Cadogan M, Buttner R (2020-10-01). "R Wave Peak Time RWPT". Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL. Retrieved 2022-01-17.

- ^ a b Brownfield J, Herbert M (January 2008). "EKG Criteria for Fibrinolysis: What's Up with the J Point?". The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 9 (1): 40–42. PMC 2672223. PMID 19561701.

- ^ "PSTF Paramedic Student Electrocardiography". Archived from the original on 2011-12-19. Retrieved 2010-03-27.

- ^ Sutin KM, Marino PL (2007). The ICU book. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-7817-4802-5.

- ^ Pan J, Tompkins WJ (March 1985). "A real-time QRS detection algorithm". IEEE Transactions on Bio-Medical Engineering. 32 (3): 230–236. doi:10.1109/TBME.1985.325532. PMID 3997178.

- ^ Nair MA (2010). "ECG Feature Extraction using Time Frequency Analysis". In Sobh T, Elleithy K (eds.). Innovations in Computing Sciences and Software Engineering. Springer. pp. 461–466 (462). Bibcode:2010iics.book..461N. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9112-3_78. ISBN 978-90-481-9111-6.

- ^ Kim SH, Kim CH, Savastyuk E, Kochiev T, Kim HS, Kim TS (2009). "Windowed Nonlinear Energy Operator-based First-arrival Pulse Detection for Ultrasound Transmission Computed Tomography". In Lim CT, Hong JG (eds.). 13th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering. IFMBE Proceedings. Vol. 23. Springer. pp. 468–471 (469). doi:10.1007/978-3-540-92841-6_115. ISBN 978-3-540-92840-9.

- ^ Chaudhuri S, Pawar TD, Duttagupta S (2009). Ambulation Analysis in Wearable ECG. Springer. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-4419-0725-7.

- ^ Singh HR, Sharma R, Sahgal N, Sethi P, Kushwah R, Kachhawa P (2010). "An improved method of measurement of ECG parameters for online medical diagnosis". Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 156 (Medical and Care Compunetics 6): 40–46. doi:10.3233/978-1-60750-565-5-40. PMID 20543337.

- ^ Köhler BU, Hennig C, Orglmeister R (2002). "The principles of software QRS detection". IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine. 21 (1): 42–57. Bibcode:2002IEMBM..21a..42K. doi:10.1109/51.993193. PMID 11935987.

- ^ Koka, Taulant; Muma, Michael (2022). "Fast and Sample Accurate R-Peak Detection for Noisy ECG Using Visibility Graphs". 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). pp. 121–126. doi:10.1109/embc48229.2022.9871266. ISBN 978-1-7281-2782-8. PMID 36086455.

- ^ Emrich, Jonas; Koka, Taulant; Wirth, Sebastian; Muma, Michael (2023). "Accelerated Sample-Accurate R-Peak Detectors Based on Visibility Graphs". 2023 31st European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO). pp. 1090–1094. doi:10.23919/eusipco58844.2023.10290007. ISBN 978-9-4645-9360-0.