Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Quasigroup

View on Wikipedia

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (February 2024) |

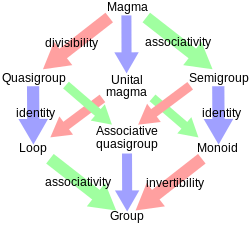

In mathematics, especially in abstract algebra, a quasigroup is an algebraic structure that resembles a group in the sense that "division" is always possible. Quasigroups differ from groups mainly in that the associative and identity element properties are optional. In fact, a nonempty associative quasigroup is a group.[1][2]

A quasigroup that has an identity element is called a loop[3].

| Algebraic structures |

|---|

Definitions

[edit]There are at least two structurally equivalent formal definitions of a quasigroup:

- One defines a quasigroup as a set with one binary operation.

- The other, from universal algebra, defines a quasigroup as having three primitive operations.

The homomorphic image of a quasigroup that is defined with a single binary operation, however, need not be a quasigroup, in contrast to a quasigroup as having three primitive operations.[4] We begin with the first definition.

Algebra

[edit]A quasigroup (Q, ∗) is a set Q with a binary operation ∗ (that is, a magma, indicating that a quasigroup has to satisfy the closure property), obeying the Latin square property. This states that, for each a and b in Q, there exist unique elements x and y in Q such that both hold. (In other words: Each element of the set occurs exactly once in each row and exactly once in each column of the quasigroup's multiplication table, or Cayley table. This property ensures that the Cayley table of a finite quasigroup, and, in particular, a finite group, is a Latin square.) The requirement that x and y be unique can be replaced by the requirement that the magma be cancellative.[5][a]

The unique solutions to these equations are written x = a \ b and y = b / a. The operations '\' and '/' are called, respectively, left division and right division. With regard to the Cayley table, the first equation (left division) means that the b entry in the a row is in the x column while the second equation (right division) means that the b entry in the a column is in the y row.

The empty set equipped with the empty binary operation satisfies this definition of a quasigroup. Some authors accept the empty quasigroup, but others explicitly exclude it.[6][7]

Universal algebra

[edit]Given some algebraic structure, an identity is an equation in which all variables are tacitly universally quantified, and in which all operations are among the primitive operations proper to the structure. Algebraic structures that satisfy axioms that are given solely by identities are called varieties. Many standard results in universal algebra hold only for varieties. Quasigroups form a variety if left and right division are taken as primitive.

A right-quasigroup (Q, ∗, /) is a type (2, 2) algebra that satisfies the identities:

A left-quasigroup (Q, ∗, \) is a type (2, 2) algebra that satisfies the identities:

A quasigroup (Q, ∗, \, /) is a type (2, 2, 2) algebra (i.e., equipped with three binary operations) that satisfies the identities:[b]

In other words: Multiplication and division in either order, one after the other, on the same side by the same element, have no net effect.

Hence if (Q, ∗) is a quasigroup according to the definition of the previous section, then (Q, ∗, \, /) is the same quasigroup in the sense of universal algebra. And vice versa: if (Q, ∗, \, /) is a quasigroup according to the sense of universal algebra, then (Q, ∗) is a quasigroup according to the first definition.

Loops

[edit]A loop is a quasigroup with an identity element; that is, an element, e, such that

- x ∗ e = x and e ∗ x = x for all x in Q.

It follows that the identity element, e, is unique, and that every element of Q has unique left and right inverses (which need not be the same). Since the presence of an identity element is essential, a loop cannot be empty.

A quasigroup with an idempotent element is called a pique ("pointed idempotent quasigroup"); this is a weaker notion than a loop but common nonetheless because, for example, given an abelian group, (A, +), taking its subtraction operation as quasigroup multiplication yields a pique (A, −) with the group identity (zero) turned into a "pointed idempotent". (That is, there is a principal isotopy (x, y, z) ↦ (x, −y, z).)

A loop that is associative is a group. A group can have a strictly nonassociative pique isotope, but it cannot have a strictly nonassociative loop isotope.

There are weaker associativity properties that have been given special names.

For instance, a Bol loop is a loop that satisfies either:

- x ∗ (y ∗ (x ∗ z)) = (x ∗ (y ∗ x)) ∗ z for each x, y and z in Q (a left Bol loop),

or else

- ((z ∗ x) ∗ y) ∗ x = z ∗ ((x ∗ y) ∗ x) for each x, y and z in Q (a right Bol loop).

A loop that is both a left and right Bol loop is a Moufang loop. This is equivalent to any one of the following single Moufang identities holding for all x, y, z:

- x ∗ (y ∗ (x ∗ z)) = ((x ∗ y) ∗ x) ∗ z

- z ∗ (x ∗ (y ∗ x)) = ((z ∗ x) ∗ y) ∗ x

- (x ∗ y) ∗ (z ∗ x) = x ∗ ((y ∗ z) ∗ x)

- (x ∗ y) ∗ (z ∗ x) = (x ∗ (y ∗ z)) ∗ x.

According to Jonathan D. H. Smith, "loops" were named after the Chicago Loop, as their originators were studying quasigroups in Chicago at the time.[10]

Symmetries

[edit]Smith (2007) names the following important properties and subclasses:

Semisymmetry

[edit]A quasigroup is semisymmetric if any of the following equivalent identities hold for all x, y:[c]

- x ∗ y = y / x

- y ∗ x = x \ y

- x = (y ∗ x) ∗ y

- x = y ∗ (x ∗ y).

Although this class may seem special, every quasigroup Q induces a semisymmetric quasigroup QΔ on the direct product cube Q3 via the following operation:

- (x1, x2, x3) ⋅ (y1, y2, y3) = (y3 / x2, y1 \ x3, x1 ∗ y2) = (x2 // y3, x3 \\ y1, x1 ∗ y2),

where "//" and "\\" are the conjugate division operations given by y // x = x / y and y \\ x = x \ y.

Triality

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2015) |

A quasigroup may exhibit semisymmetric triality.[11]

Total symmetry

[edit]A narrower class is a totally symmetric quasigroup (sometimes abbreviated TS-quasigroup) in which all conjugates coincide as one operation: x ∗ y = x / y = x \ y. Another way to define (the same notion of) totally symmetric quasigroup is as a semisymmetric quasigroup that is commutative, i.e. x ∗ y = y ∗ x.

Idempotent total symmetric quasigroups are precisely (i.e. in a bijection with) Steiner triples, so such a quasigroup is also called a Steiner quasigroup, and sometimes the latter is even abbreviated as squag. The term sloop refers to an analogue for loops, namely, totally symmetric loops that satisfy x ∗ x = 1 instead of x ∗ x = x. Without idempotency, total symmetric quasigroups correspond to the geometric notion of extended Steiner triple, also called Generalized Elliptic Cubic Curve (GECC).

Total antisymmetry

[edit]A quasigroup (Q, ∗) is called weakly totally anti-symmetric if for all c, x, y ∈ Q, the following implication holds.[12]

- (c ∗ x) ∗ y = (c ∗ y) ∗ x implies that x = y.

A quasigroup (Q, ∗) is called totally anti-symmetric if, in addition, for all x, y ∈ Q, the following implication holds:[12]

- x ∗ y = y ∗ x implies that x = y.

This property is required, for example, in the Damm algorithm.

Examples

[edit]- Every group is a loop, because a ∗ x = b if and only if x = a−1 ∗ b, and y ∗ a = b if and only if y = b ∗ a−1.

- The integers Z (or the rationals Q or the reals R) with subtraction (−) form a quasigroup. These quasigroups are not loops because there is no identity element (0 is a right identity because a − 0 = a, but not a left identity because, in general, 0 − a ≠ a).

- The nonzero rationals Q× (or the nonzero reals R×) with division (÷) form a quasigroup.

- Any vector space over a field of characteristic not equal to 2 forms an idempotent, commutative quasigroup under the operation x ∗ y = (x + y) / 2.

- Every Steiner triple system defines an idempotent, commutative quasigroup: a ∗ b is the third element of the triple containing a and b. These quasigroups also satisfy (x ∗ y) ∗ y = x for all x and y in the quasigroup. These quasigroups are known as Steiner quasigroups.[13]

- The set {±1, ±i, ±j, ±k} where ii = jj = kk = +1 and with all other products as in the quaternion group forms a nonassociative loop of order 8. See hyperbolic quaternions for its application. (The hyperbolic quaternions themselves do not form a loop or quasigroup.)

- The nonzero octonions form a nonassociative loop under multiplication. The octonions are a special type of loop known as a Moufang loop.

- An associative quasigroup is either empty or is a group, since if there is at least one element, the invertibility of the quasigroup binary operation combined with associativity implies the existence of an identity element, which then implies the existence of inverse elements, thus satisfying all three requirements of a group.

- The following construction is due to Hans Zassenhaus. On the underlying set of the four-dimensional vector space F4 over the 3-element Galois field F = Z/3Z define

- (x1, x2, x3, x4) ∗ (y1, y2, y3, y4) = (x1, x2, x3, x4) + (y1, y2, y3, y4) + (0, 0, 0, (x3 − y3)(x1y2 − x2y1)).

- Then, (F4, ∗) is a commutative Moufang loop that is not a group.[14]

- More generally, the nonzero elements of any division algebra form a quasigroup with the operation of multiplication in the algebra.

Properties

[edit]- In the remainder of the article we shall denote quasigroup multiplication simply by juxtaposition.

Quasigroups have the cancellation property: if ab = ac, then b = c. This follows from the uniqueness of left division of ab or ac by a. Similarly, if ba = ca, then b = c.

The Latin square property of quasigroups implies that, given any two of the three variables in xy = z, the third variable is uniquely determined.

Multiplication operators

[edit]The definition of a quasigroup can be treated as conditions on the left and right multiplication operators Lx, Rx : Q → Q, defined by

- Lx(y) = xy

- Rx(y) = yx

The definition says that both mappings are bijections from Q to itself. A magma Q is a quasigroup precisely when all these operators, for every x in Q, are bijective. The inverse mappings are left and right division, that is,

- L−1

x(y) = x \ y - R−1

x(y) = y / x

In this notation the identities among the quasigroup's multiplication and division operations (stated in the section on universal algebra) are

- LxL−1

x = id corresponding to x(x \ y) = y - L−1

xLx = id corresponding to x \ (xy) = y - RxR−1

x = id corresponding to (y / x)x = y - R−1

xRx = id corresponding to (yx) / x = y

where id denotes the identity mapping on Q.

Latin squares

[edit]| 0 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 5 |

| 3 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 4 |

| 8 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| 1 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| 2 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| 5 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 6 |

| 4 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 1 |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 9 | 0 |

The multiplication table of a finite quasigroup is a Latin square: an n × n table filled with n different symbols in such a way that each symbol occurs exactly once in each row and exactly once in each column.

Conversely, every Latin square can be taken as the multiplication table of a quasigroup in many ways: the border row (containing the column headers) and the border column (containing the row headers) can each be any permutation of the elements. See Small Latin squares and quasigroups.

Infinite quasigroups

[edit]For a countably infinite quasigroup Q, it is possible to imagine an infinite array in which every row and every column corresponds to some element q of Q, and where the element a ∗ b is in the row corresponding to a and the column responding to b. In this situation too, the Latin square property says that each row and each column of the infinite array will contain every possible value precisely once.

For an uncountably infinite quasigroup, such as the group of non-zero real numbers under multiplication, the Latin square property still holds, although the name is somewhat unsatisfactory, as it is not possible to produce the array of combinations to which the above idea of an infinite array extends since the real numbers cannot all be written in a sequence. (This is somewhat misleading however, as the reals can be written in a sequence of length , assuming the well-ordering theorem.)

Inverse properties

[edit]The binary operation of a quasigroup is invertible in the sense that both Lx and Rx, the left and right multiplication operators, are bijective, and hence invertible.

Every loop element has a unique left and right inverse given by

- xλ = e / x xλx = e

- xρ = x \ e xxρ = e

A loop is said to have (two-sided) inverses if xλ = xρ for all x. In this case the inverse element is usually denoted by x−1.

There are some stronger notions of inverses in loops that are often useful:

- A loop has the left inverse property if xλ(xy) = y for all x and y. Equivalently, L−1

x = Lxλ or x \ y = xλy. - A loop has the right inverse property if (yx)xρ = y for all x and y. Equivalently, R−1

x = Rxρ or y / x = yxρ. - A loop has the antiautomorphic inverse property if (xy)λ = yλxλ or, equivalently, if (xy)ρ = yρxρ.

- A loop has the weak inverse property when (xy)z = e if and only if x(yz) = e. This may be stated in terms of inverses via (xy)λx = yλ or equivalently x(yx)ρ = yρ.

A loop has the inverse property if it has both the left and right inverse properties. Inverse property loops also have the antiautomorphic and weak inverse properties. In fact, any loop that satisfies any two of the above four identities has the inverse property and therefore satisfies all four.

Any loop that satisfies the left, right, or antiautomorphic inverse properties automatically has two-sided inverses.

Morphisms

[edit]A quasigroup or loop homomorphism is a map f : Q → P between two quasigroups such that f(xy) = f(x)f(y). Quasigroup homomorphisms necessarily preserve left and right division, as well as identity elements (if they exist).

Homotopy and isotopy

[edit]Let Q and P be quasigroups. A quasigroup homotopy from Q to P is a triple (α, β, γ) of maps from Q to P such that

- α(x)β(y) = γ(xy)

for all x, y in Q. A quasigroup homomorphism is just a homotopy for which the three maps are equal.

An isotopy is a homotopy for which each of the three maps (α, β, γ) is a bijection. Two quasigroups are isotopic if there is an isotopy between them. In terms of Latin squares, an isotopy (α, β, γ) is given by a permutation of rows α, a permutation of columns β, and a permutation on the underlying element set γ.

An autotopy is an isotopy from a quasigroup to itself. The set of all autotopies of a quasigroup forms a group with the automorphism group as a subgroup.

Every quasigroup is isotopic to a loop. If a loop is isotopic to a group, then it is isomorphic to that group and thus is itself a group. However, a quasigroup that is isotopic to a group need not be a group. For example, the quasigroup on R with multiplication given by (x, y) ↦ (x + y)/2 is isotopic to the additive group (R, +), but is not itself a group as it has no identity element. Every medial quasigroup is isotopic to an abelian group by the Bruck–Toyoda theorem.

Conjugation (parastrophe)

[edit]Left and right division are examples of forming a quasigroup by permuting the variables in the defining equation. From the original operation ∗ (i.e., x ∗ y = z) we can form five new operations: x o y := y ∗ x (the opposite operation), / and \, and their opposites. That makes a total of six quasigroup operations, which are called the conjugates or parastrophes of ∗. Any two of these operations are said to be "conjugate" or "parastrophic" to each other (and to themselves).

Isostrophe (paratopy)

[edit]If the set Q has two quasigroup operations, ∗ and ·, and one of them is isotopic to a conjugate of the other, the operations are said to be isostrophic to each other. There are also many other names for this relation of "isostrophe", e.g., paratopy.

Generalizations

[edit]Polyadic or multiary quasigroups

[edit]An n-ary quasigroup is a set with an n-ary operation, (Q, f) with f : Qn → Q, such that the equation f(x1, ..., xn) = y has a unique solution for any one variable if all the other n variables are specified arbitrarily. Polyadic or multiary means n-ary for some nonnegative integer n.

A 0-ary, or nullary, quasigroup is just a constant element of Q. A 1-ary, or unary, quasigroup is a bijection of Q to itself. A binary, or 2-ary, quasigroup is an ordinary quasigroup.

An example of a multiary quasigroup is an iterated group operation, y = x1 · x2 · ··· · xn; it is not necessary to use parentheses to specify the order of operations because the group is associative. One can also form a multiary quasigroup by carrying out any sequence of the same or different group or quasigroup operations, if the order of operations is specified.

There exist multiary quasigroups that cannot be represented in any of these ways. An n-ary quasigroup is irreducible if its operation cannot be factored into the composition of two operations in the following way:

- f(x1, ..., xn) = g(x1, ..., xi−1, h(xi, ..., xj), xj+1, ..., xn),

where 1 ≤ i < j ≤ n and (i, j) ≠ (1, n). Finite irreducible n-ary quasigroups exist for all n > 2; see Akivis & Goldberg (2001) for details.

An n-ary quasigroup with an n-ary version of associativity is called an n-ary group.

Number of small quasigroups and loops

[edit]The number of isomorphism classes of small quasigroups (sequence A057991 in the OEIS) and loops (sequence A057771 in the OEIS) is given here:[15]

| Order | Number of quasigroups | Number of loops |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 5 | 1 |

| 4 | 35 | 2 |

| 5 | 1411 | 6 |

| 6 | 1130531 | 109 |

| 7 | 12198455835 | 23746 |

| 8 | 2697818331680661 | 106228849 |

| 9 | 15224734061438247321497 | 9365022303540 |

| 10 | 2750892211809150446995735533513 | 20890436195945769617 |

| 11 | 19464657391668924966791023043937578299025 | 1478157455158044452849321016 |

See also

[edit]- Division ring – a ring in which every non-zero element has a multiplicative inverse

- Semigroup – an algebraic structure consisting of a set together with an associative binary operation

- Monoid – a semigroup with an identity element

- Planar ternary ring – has an additive and multiplicative loop structure

- Problems in loop theory and quasigroup theory

- Mathematics of Sudoku

Notes

[edit]- ^ For clarity, cancellativity alone is insufficient: the requirement for existence of a solution must be retained.

- ^ There are six identities that these operations satisfy, namely:[8] Of these, the first three imply the last three, and vice versa, leading to either set of three identities being sufficient to equationally specify a quasigroup.[9]

- ^ The first two equations are equivalent to the last two by direct application of the cancellation property of quasigroups. The last pair are shown to be equivalent by setting x = ((x ∗ y) ∗ x) ∗ (x ∗ y) = y ∗ (x ∗ y).

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Nonempty associative quasigroup equals group

- ^ an associative quasigroup is a group

- ^ https://www.arcjournals.org/pdfs/ijsimr/v1-i2/V1-I2-5.pdf

- ^ Smith 2007, pp. 3, 26–27

- ^ Rubin & Rubin 1985, p. 109

- ^ Pflugfelder 1990, p. 2

- ^ Bruck 1971, p. 1

- ^ Shcherbacov, Pushkashu & Shcherbacov 2021, p. 1

- ^ Shcherbacov, Pushkashu & Shcherbacov 2021, p. 3, Thm. 1, 2

- ^ Smith, Jonathan D. H. (2 April 2024). "Codes, Errors, and Loops". Recording of the Codes & Expansions Seminar. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Smith, Jonathan D. H. Groups, Triality, and Hyperquasigroups (PDF). Iowa State University.

- ^ a b Damm 2007

- ^ Colbourn & Dinitz 2007, p. 497, definition 28.12

- ^ Romanowska & Smith 1999, p. 93

- ^ McKay, Meynert & Myrvold 2007

Sources

[edit]- Akivis, M.A.; Goldberg, Vladislav V. (2001). "Solution of Belousov's problem". Discussiones Mathematicae – General Algebra and Applications. 21 (1): 93–103. arXiv:math/0010175. doi:10.7151/dmgaa.1030. S2CID 18421746.

- Belousov, V.D. (1967). Foundations of the Theory of Quasigroups and Loops (in Russian). Moscow: Izdat. "Nauka". OCLC 472241611.

- Belousov, V.D. (1971). Algebraic Nets and Quasigroups (in Russian). Kishinev: Izdat. "Štiinca". OCLC 8292276.

- Belousov, V.D. (1981). Elements of Quasigroup Theory: a Special Course (in Russian). Kishinev: Kishinev State University Printing House. OCLC 318458899.

- Bruck, R.H. (1971) [1958]. A Survey of Binary Systems. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-03497-3.

- Chein, O.; Pflugfelder, H.O.; Smith, J.D.H., eds. (1990). Quasigroups and Loops: Theory and Applications. Berlin: Heldermann. ISBN 978-3-88538-008-5.

- Colbourn, Charles J.; Dinitz, Jeffrey H. (2007), Handbook of Combinatorial Designs (2nd ed.), CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-58488-506-1

- Damm, H. Michael (2007). "Totally anti-symmetric quasigroups for all orders n ≠ 2, 6". Discrete Mathematics. 307 (6): 715–729. doi:10.1016/j.disc.2006.05.033.

- Dudek, W.A.; Glazek, K. (2008). "Around the Hosszu-Gluskin Theorem for n-ary groups". Discrete Math. 308 (21): 4861–76. arXiv:math/0510185. doi:10.1016/j.disc.2007.09.005. S2CID 9545943.

- McKay, Brendan D.; Meynert, Alison; Myrvold, Wendy (2007). "Small Latin squares, quasigroups, and loops" (PDF). J. Comb. Des. 15 (2): 98–119. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.151.3043. doi:10.1002/jcd.20105. S2CID 82321. Zbl 1112.05018.

- Pflugfelder, H.O. (1990). Quasigroups and Loops: Introduction. Berlin: Heldermann. ISBN 978-3-88538-007-8.

- Romanowska, Anna B.; Smith, Jonathan D.H. (1999), "Example 4.1.3 (Zassenhaus's Commutative Moufang Loop)", Post-modern algebra, Pure and Applied Mathematics, New York: Wiley, doi:10.1002/9781118032589, ISBN 978-0-471-12738-3, MR 1673047

- Rubin, H.; Rubin, J.E. (1985). Equivalents of the Axiom of Choice, II. Elsevier.

- Shcherbacov, V.A. (2017). Elements of Quasigroup Theory and Applications. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4987-2155-4.

- Shcherbacov, V.A.; Pushkashu, D.I.; Shcherbacov, A.V. (2021). "Equational quasigroup definitions". arXiv:1003.3175v1 [math.GR].

- Smith, J.D.H. (2007). An Introduction to Quasigroups and their Representations. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-58488-537-5.

External links

[edit]- quasigroups Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- "Quasi-group", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

Quasigroup

View on GrokipediaDefinitions

Algebraic Definition

A quasigroup is an algebraic structure consisting of a set together with a binary operation such that, for all , the equations and possess unique solutions . This divisibility condition implies that the left multiplication map defined by and the right multiplication map defined by are bijective for every .[9][10] The unique solvability enables the definition of division operations within the quasigroup. The right division is the unique element satisfying , while the left division is the unique element satisfying . These operations extend the binary structure into a partial magma with inverses in a generalized sense, distinguishing quasigroups from more restrictive structures like groups, which additionally require associativity and an identity element.[10][4] For a finite quasigroup of order , the multiplication table—where rows and columns are indexed by elements of and entries are given by the operation—forms a Latin square of order . In this square, each symbol from appears exactly once in every row and every column, reflecting the bijectivity of the multiplication maps. This connection underscores the combinatorial significance of quasigroups.[9] The concept of quasigroups emerged in the 1930s, with the term "quasigroup" coined by Ruth Moufang in her investigations of non-Desarguesian projective planes, where such structures arose naturally. This development built upon Leonhard Euler's foundational 18th-century work on Latin squares, including his studies of orthogonal arrays and the 36 officers problem.[9][11] A simple infinite example is the set of integers under subtraction, denoted , where . For any , the equation solves uniquely to , and solves to , satisfying the quasigroup axioms. Loops, which are quasigroups equipped with a two-sided identity element, provide a natural extension of this structure.[10]Universal Algebra Definition

In universal algebra, a quasigroup is defined as the algebra consisting of a set equipped with three binary operations: multiplication , right division , and left division , satisfying the identities for all .[12] These identities ensure that the equations and are uniquely solvable for and , respectively, with the divisions providing the unique solutions.[13] This equational definition with three primitive operations is equivalent to the combinatorial definition using a single binary operation where left and right translations are bijective permutations of . Specifically, given a binary quasigroup , the division operations are uniquely determined by setting as the unique such that and as the unique such that ; conversely, the multiplication operation is uniquely determined by the division operations satisfying the defining identities.[13] The class of all quasigroups forms a variety in the sense of universal algebra, meaning it is defined by identities and thus closed under the formation of subalgebras, homomorphic images, and arbitrary direct products.[12] A derived ternary operation on a quasigroup can be introduced as , where the equality holds by a derived identity of quasigroups ensuring consistency between left and right solvability; this ternary operation satisfies the projection identities and , and more generally the five-variable identities .[12] The left and right multiplications are defined as the maps given by and given by for each ; the defining identities imply that each and is a bijection (permutation) on .[13]Basic Structures

Loops

A loop is a quasigroup equipped with a two-sided identity element satisfying for all .[14] This structure generalizes groups by relaxing the associativity axiom while preserving the ability to perform unique divisions. The term "loop" was coined in the early 1940s by A. A. Albert and his collaborators in Chicago, evoking the city's famous Loop district and rhyming with "group."[15] Every loop is a quasigroup, as the presence of the identity ensures that left and right multiplications remain bijective, allowing unique solutions to equations of the form and . However, the converse fails: not every quasigroup is a loop, since some lack an identity element. A standard example is the set of integers under subtraction, where ; this operation yields a quasigroup, as divisions are uniquely solvable (e.g., solving gives ), but no element satisfies for all .[16] In a loop, each element admits a unique left inverse such that and a unique right inverse such that , with and not necessarily equal in non-associative cases. These inverses follow directly from the quasigroup divisions: and . Groups provide the associative case of loops, where left and right inverses coincide and the operation satisfies for all . A prominent non-associative example arises from the multiplication of nonzero octonions, which forms a loop (specifically, a Moufang loop) on the 8-dimensional real vector space excluding zero.[14]Latin Squares

A quasigroup on a finite set of order is in one-to-one correspondence with an Latin square, where the Cayley table of the quasigroup—listing the products for elements in the set—serves as the Latin square, with rows and columns indexed by the elements and entries being the symbols from the set.[17] This bijection arises because the quasigroup axioms ensure that left and right multiplications are bijective, guaranteeing that each symbol appears exactly once in every row and column of the table.[17] Conversely, any Latin square defines a quasigroup operation via its table, as the unique entry in each position satisfies the solvability conditions for the quasigroup equations.[18] If the Latin square is reduced—meaning its first row and first column are in natural order (1 to )—then the corresponding quasigroup is a loop, possessing a two-sided identity element.[17] More generally, two quasigroups are isotopic if there exist bijections on the underlying set such that for all , and this relation corresponds precisely to the isotopism of their associated Latin squares, where an isotopism is a triple of permutations on rows, columns, and symbols that transforms one square into the other.[17] Isotopic quasigroups thus share structural similarities, such as having isomorphic multiplication groups, though they may differ in properties like the presence of an identity.[8] Latin squares associated with quasigroups can be constructed using orthogonal mates: if a Latin square has an orthogonal mate —another Latin square such that the pairs are all distinct—then combining them yields a set of mutually orthogonal Latin squares, each corresponding to a quasigroup operation that can be composed to form more complex structures.[17] A prominent construction yields Steiner quasigroups from finite projective planes: given a projective plane of order (with points), the points form the underlying set of a Steiner quasigroup satisfying the identities , , and , where the operation is defined geometrically using lines of the plane, and its Cayley table is a symmetric idempotent Latin square.[19] Such quasigroups exist whenever a projective plane of order does, which occurs for all prime power .[20] The bijection extends to infinite quasigroups: for any set , a quasigroup operation on yields a (possibly infinite) Latin square indexed by , where each row and column is a bijection from to itself, ensuring unique solvability of the quasigroup equations. In the countable infinite case, this corresponds to a countable Latin square, as seen in constructions over infinite sets like the rationals or integers under suitable operations, maintaining the bijective multiplication properties without finiteness restrictions.[18]Examples

Finite Quasigroups

The quasigroup of order 1 consists of a single element with the operation defined by . This structure is a loop, serving as the trivial example where the unique element acts as the identity.[21] For order 2, there is a unique quasigroup up to isomorphism, given by the set with the multiplication table: This quasigroup is a loop with identity , isomorphic to the cyclic group .[21] Of order 3, there exist five non-isomorphic quasigroups, only one of which is a loop: the cyclic group under addition, with elements and operation modulo 3. The remaining four are non-loops, illustrating early examples where the Latin square representation yields distinct algebraic structures without an identity element.[21] Quasigroups also arise from finite fields through planar functions, which generate commutative quasigroups on the field elements and coordinatize affine planes. For a finite field and a planar function , the operation defines a commutative quasigroup whose properties reflect the geometric structure of the associated affine plane of order . These quasigroups are quasifields when equipped with additional division properties, enabling the construction of non-Desarguesian affine planes.[22] Steiner triple systems provide another construction of idempotent quasigroups. Given a Steiner triple system STS() on a set of or points, define the operation by for all , and for , where is the unique triple containing and . The resulting quasigroup is idempotent, commutative, and totally symmetric, with the property that and . This correspondence links combinatorial designs directly to algebraic structures, as seen in the Fano plane yielding an STS(7) and its associated quasigroup.[23]Infinite Quasigroups

Infinite quasigroups arise in various algebraic contexts, providing structures on infinite sets where the operation ensures unique solvability of equations without requiring associativity or an identity element. A prominent example is the set of integers equipped with the subtraction operation, defined by . This forms a quasigroup because, for any fixed , the equations (solving for ) and (solving for ) have unique solutions, and similarly for other combinations. However, it is not a loop, as there is no identity element satisfying and for all .[24][14] Similarly, the real numbers under subtraction constitute an infinite quasigroup. The operation is closed, and the left and right multiplications are bijective: solving yields , and yields , with unique solutions in . Like the integer case, it lacks an identity element, rendering it a non-loop quasigroup. This structure extends the additive group via conjugation, highlighting how quasigroups can be derived from groups by altering the operation.[14] Vector spaces over fields also yield infinite quasigroups when equipped with componentwise subtraction. Consider a vector space over a field (such as or ), viewed as for some infinite cardinal (e.g., countable dimension), with the operation for each component index . Since under subtraction is a quasigroup, the componentwise extension preserves the property: each equation has a unique componentwise solution, as the operations act independently in each coordinate. This construction generalizes to arbitrary infinite-dimensional spaces, providing quasigroups of any desired infinite cardinality.[14] Free quasigroups offer another fundamental class of infinite examples. The free quasigroup generated by a set is the free algebra in the variety of quasigroups on the generators , constructed as the free extension of the empty partial Latin square on . For infinite , the cardinality of this free quasigroup is , as the terms are finite expressions in the three binary operations (multiplication, left division, right division) modulo the quasigroup axioms, yielding a set of size at most under the axiom of choice. These structures are universal objects embedding any map from into a quasigroup.[14] Beyond specific constructions, the diversity of infinite quasigroups is vast. For each infinite cardinal , there exist uncountably many pairwise non-isomorphic quasigroups of cardinality . This abundance is exemplified in subclasses like Steiner quasigroups, where strongly minimal Steiner triple systems (each coordinatizable by a quasigroup) include uncountably many non-isomorphic models of countable cardinality.[25]Symmetries

Semisymmetry

A quasigroup is semisymmetric if it satisfies the identity for all .[26] This condition ensures a form of cyclic symmetry in the multiplication table under the action of the cyclic group .[26] Equivalent characterizations include the identity , or , or .[27] In terms of translations, semisymmetry holds if and only if, for every , the left translation and the right translation are mutual inverses, satisfying and .[28] Examples of semisymmetric quasigroups include structures derived from abelian groups equipped with the operation .[28] For instance, the integers under this operation form an infinite semisymmetric quasigroup. Semisymmetric quasigroups also arise in combinatorial designs, such as extended Mendelsohn triple systems, where blocks correspond to cyclically ordered submultisets of .[26] Semisymmetric quasigroups are flexible, satisfying the identity for all , since both sides equal by the defining identities.[27]Triality

In quasigroup theory, triality refers to a specific cyclic symmetry in the language of quasigroups, arising from the natural action of the alternating group (the cyclic subgroup of order 3 in ) on the six parastrophes (conjugate operations) of the quasigroup, preserving the structure under cyclic permutations of the operation symbols.[29] This symmetry is equivalently expressed in binary terms as for all , where denotes right division and denotes left division; this equality implies that the left and right division operations coincide after a swap of arguments, reflecting the cyclic interchange.[29] Quasigroups exhibiting triality thus possess a balanced divisibility that aligns the solving mechanisms symmetrically. Examples of quasigroups with triality include commutative Moufang loops of exponent 3, where the operation satisfies (the identity) for all , ensuring the multiplication group admits a triality automorphism.[30] Certain Steiner quasigroups, derived from Steiner triple systems and characterized by total symmetry (full -invariance), also possess triality as a subgroup symmetry, with the quasigroup operation yielding idempotent, commutative structures where every pair of distinct elements appears uniquely in a "triple."[26] Historically, the concept of triality in algebraic structures like quasigroups draws analogy from Élie Cartan's 1925 introduction of triality for the exceptional Lie group of type , later connected to the automorphism group of the octonions, which exhibit similar cyclic symmetries in their multiplication; this link has influenced studies of Moufang loops and exceptional geometries arising from quasigroups with triality.[31]Total Symmetry

A totally symmetric quasigroup is a quasigroup in which the relation holds if and only if it holds after any permutation of , , and .[32] Equivalently, for all , implies , , , , and . This condition ensures that all six parastrophes of the quasigroup—the original multiplication and the four division operations—coincide as the same binary operation on .[33] Consequently, a totally symmetric quasigroup is both commutative, satisfying for all , and semi-symmetric, satisfying for all ; the latter is a weaker property than total symmetry, as it does not require commutativity.[26] The commutativity of a totally symmetric quasigroup implies that its left multiplication maps coincide with its right multiplication maps for every . Moreover, the semi-symmetry condition forces each such map to be an involution, satisfying . These symmetries extend to the division operations, making the quasigroup highly symmetric in its algebraic structure. While the variety of totally symmetric quasigroups is defined by these permutation identities, not all members satisfy additional identities such as mediality, , though medial totally symmetric quasigroups form an important subclass with applications in abelian group isotopes.[34] Examples of totally symmetric quasigroups include the elementary abelian $2(\mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z} \times \mathbb{Z}/2\mathbb{Z}, +)\mathbb{F}_2x + (y + x) = y2x = 0\mathbb{F}_2 with componentwise addition yields a totally symmetric quasigroup, providing infinite examples as well. A finite non-group example arises from the cyclic group of order $3 with a modified operation, but such constructions are limited; in fact, the only groups that are totally symmetric quasigroups are precisely the elementary abelian $2$-groups.[35] Totally symmetric idempotent quasigroups, which additionally satisfy for all , are closely connected to combinatorial designs. Specifically, given such a quasigroup on a set , the collection of triples forms a Steiner triple system of order , where every pair from appears in exactly one triple. Conversely, every Steiner triple system on determines a unique idempotent totally symmetric quasigroup on by defining if is a triple in the system (and ). This correspondence links total symmetry to finite geometries and design theory.[13]Total Antisymmetry

A totally antisymmetric quasigroup, also known as a totally anti-symmetric (TA) quasigroup, is an idempotent quasigroup (Q, ·) in which x · x = x for all x ∈ Q, and the operation is anticommutative in the weak sense that x · y = y · x implies x = y for all x, y ∈ Q.[36] To achieve "total" antisymmetry for applications such as error detection, the structure additionally satisfies that for all c, x, y ∈ Q, (c · x) · y = (c · y) · x implies x = y, ensuring that adjacent transpositions alter the result unless the transposed elements are equal.[36] In additive notation, the operation often takes the form x + y ≡ - (y + x) \pmod{n} for finite orders n, reflecting the skew-symmetry of the multiplication table where entries in symmetric positions sum to 0 modulo n. Such quasigroups exist for every finite order n except n=2 and n=6.[36] These quasigroups are related to anticommutative magmas, where the operation opposes commutativity, and the idempotence property aligns with involutory behavior in loop contexts, though TA quasigroups are typically not loops due to the fixed-point-free nature of loop identities.[36] If the quasigroup is a loop with identity e, the idempotence generalizes to x · x = e, making the operation involutory and reinforcing the anticommutative structure by ensuring each element is its own inverse in a paired sense. The division operations in quasigroups provide the unique solvability required for this symmetry, as the right division y / x solves y · z = x, linking the antisymmetry to the bijectivity of multiplications. Examples include finite TA quasigroups of order 10 used in the Damm check digit algorithm, where the multiplication table is constructed to satisfy the antisymmetry conditions for error detection in decimal codes.[36] Infinite examples arise in vector spaces equipped with cross product-like operations that can be extended to quasigroup structures in higher odd-dimensional spaces with compatible bilinear forms.[36]Properties

Multiplication Operators

In a quasigroup , the left multiplication operator by a fixed element is the map defined by for all , while the right multiplication operator is given by . These operators arise naturally from the binary operation and capture the action of multiplication from each side.[13][8] The bijectivity of and follows directly from the quasigroup axioms, which guarantee unique solvability of the equations and for any ; thus, both maps are permutations of . This property embeds the quasigroup into the symmetric group via the left regular representation given by , and analogously via the right regular representation . These representations provide a permutation-based view of the quasigroup structure, where the image of (or ) acts regularly on .[13][37][8] For loops, which are quasigroups equipped with an identity element satisfying for all , the operators and coincide with the identity permutation on , thereby fixing the identity. In general quasigroups (without requiring an identity), the sets and generate the translation group of the quasigroup, also termed the multiplication group , which is the subgroup spanned by all left and right multiplications and encodes the transitive permutation action central to quasigroup theory.[13][8][37]Inverse Properties

In quasigroups, the left inverse property (LIP) is defined by the existence of a permutation on the underlying set such that for all .[38] This condition ensures that left multiplication by can be "undone" on the left in a consistent manner, facilitating unique recovery of .[38] Analogously, the right inverse property (RIP) holds if there exists a permutation such that for all .[38] These properties strengthen the unique solvability inherent to quasigroups by introducing inverse mappings that align with the binary operation. A loop possessing both the LIP and RIP is termed an inverse property loop (IP-loop), where the permutations and coincide with the two-sided inverse map .[38] In IP-loops, the inverse operation interacts seamlessly with the groupoid structure, leading to identities such as .[39] Such loops exhibit enhanced algebraic behavior; for instance, under additional conditions like the Moufang identities, IP-loops are power-associative, meaning that powers are well-defined independently of parenthesization for all and integers . Quasigroups inherently satisfy left and right cancellation laws due to their unique solvability: if , then , and similarly for right multiplication.[40] These laws follow directly from the existence of unique solutions to the equations and for fixed .[40] In the context of inverse properties, cancellation reinforces the invertibility aspects, ensuring that distinct elements remain distinguishable under multiplication. The cross inverse property extends these ideas by requiring identities that mix division and multiplication, such as for all , where denotes left division (the unique satisfying ).[39] Equivalently, this can be expressed via permutations as or .[39] This property captures a form of "crossed" invertibility, where right inverses enable associative-like behavior in divisions, and it holds in structures like cross inverse property quasigroups (CIPQs).[39]Morphisms

Homotopy and Isotopy

In quasigroup theory, a homotopy between two quasigroups and is defined as a triple of functions satisfying the equation for all .[41] This relation generalizes the notion of a homomorphism by allowing three independent maps rather than a single structure-preserving function, capturing weaker structural similarities between the operations.[42] An isotopy is a special case of a homotopy where , , and are all bijective.[41] Isotopy defines an equivalence relation on the class of quasigroups: reflexivity holds via the identity maps, symmetry by inverting the bijections, and transitivity by composition of the triples.[37] A principal isotopy occurs when is the identity map on , effectively conjugating the operation by permutations on the left and right factors while fixing the output labeling.[37] Isotopies preserve key structural properties of quasigroups, such as the type defined by identities or the presence of an identity element. Specifically, if is a loop (a quasigroup with a two-sided identity), then any quasigroup isotopic to it is also a loop, as the image of the identity under the appropriate bijection serves as the identity in the isotope.[43] Conversely, every quasigroup is isotopic to some loop, allowing the normalization of quasigroups to this form without loss of essential structure.[43] For example, consider two quasigroups on the same finite set corresponding to Latin squares; an isotopism arises from permuting the rows (via ), columns (via ), and symbols (via ) in the multiplication table, yielding isotopic quasigroups with equivalent combinatorial properties.[41] Such transformations demonstrate how isotopy equates quasigroups that differ only in labeling, as seen in the case where a cyclic group quasigroup is principal-isotopic to another via left and right translations.[42]Parastrophe

In quasigroup theory, a parastrophe of a binary operation ⋅ on a set Q is obtained by rearranging the roles of the variables in the defining equation x ⋅ y = z, yielding up to six possible operations corresponding to the permutations of S_3, though for quasigroups these typically reduce to three distinct forms due to the unique solvability of equations. Specifically, given the left division x \ y (the unique z such that x ⋅ z = y) and right division x / y (the unique z such that z ⋅ y = x), the parastrophes include operations defined as x * y = y / x (where y / x is the unique z with z ⋅ x = y), x *' y = x \ y, and x ** y = y \ x (where y \ x is the unique z with y ⋅ z = x).[44] All parastrophes of a quasigroup are themselves quasigroups, as the latin square property is preserved under these rearrangements of the multiplication table.[45] Furthermore, if the original structure is a loop (a quasigroup with identity), each parastrophe retains the loop property, ensuring the existence of a two-sided identity in the new operation.[44] A conjugation of a quasigroup is an isotopy composed with a parastrophe, combining variable permutations with operation rearrangement to relate structures while preserving quasigroup axioms.[45] For example, in the case of groups—which are special quasigroups with associativity and inverses—all parastrophes yield structures isotopic to the original group, and thus isomorphic as groups.[45]Isostrophe

An isostrophe is defined as the composition of an isotopy and a parastrophe in quasigroup theory, specifically representing an isotopy between two parastrophes of quasigroups.[46] Parastrophes arise from reinterpreting the binary operation of a quasigroup as one of its five conjugate operations, such as left division or right division , yielding up to six distinct quasigroups associated with the original.[47] An isostrophe thus connects quasigroups that differ both in their underlying permutations (via isotopy) and in the choice of operation (via parastrophe), providing a broader equivalence relation than isotopy alone.[46] Isostrophes preserve additional structural features compared to isotopies, particularly in the multiplication groups and symmetry properties of quasigroups. For instance, if a loop is an isostrophe of a quasigroup, their middle multiplication groups coincide, and the left and right multiplication groups of the loop form normal subgroups within this structure.[46] The autotopism group of a quasigroup, which consists of triples of bijections preserving the operation, extends to include isostrophic automorphisms that account for parastrophic rearrangements, enhancing the analysis of symmetries across conjugate operations.[46] In the context of Latin squares, which are equivalent to the multiplication tables of quasigroups, isostrophes correspond to combined manipulations of orthogonal arrays. These include permuting rows, columns, and symbols (from the isotopy component) alongside conjugating the array to reflect a different operation (from the parastrophe), thereby preserving orthogonality properties in sets of mutually orthogonal Latin squares.[48]Applications

Combinatorics and Design Theory

Quasigroups find prominent applications in combinatorics and design theory through their intimate connection to Latin squares, which are precisely the multiplication tables of finite quasigroups.[21] This bijection allows quasigroup theory to underpin the algebraic study of combinatorial structures like orthogonal arrays and block designs. A historical cornerstone is Euler's 36 officers problem, posed in 1779, which seeks to arrange 36 officers—representing one from each of 6 ranks and 6 regiments—into a 6×6 square such that each row and each column contains exactly one officer from every rank and every regiment.[49] This arrangement is equivalent to constructing two mutually orthogonal Latin squares of order 6, or equivalently, two orthogonal quasigroups of order 6, where orthogonality means that the map sending each pair to (with and the respective operations) is bijective, ensuring every ordered pair of symbols appears exactly once in the superposition of their tables.[49] Euler conjectured no solution exists for order 6 (or more generally for orders congruent to 2 modulo 4), a claim later confirmed for by exhaustive enumeration, though disproven for larger such orders.[49] More broadly, sets of mutually orthogonal Latin squares (MOLS) of order arise from sets of mutually orthogonal quasigroups on an -element set, where every pair of distinct quasigroups in the set satisfies the orthogonality condition.[50] Such constructions are central to design theory, enabling the formation of orthogonal arrays OA of strength 2, which in turn yield resolvable balanced incomplete block designs and affine geometries. For instance, a complete set of MOLS corresponds to a projective plane of order , and quasigroup prolongations—extensions preserving Latin square properties—facilitate explicit constructions of orthogonal pairs, as demonstrated for order 10 using T-quasigroups.[50] In the realm of Steiner triple systems, idempotent commutative quasigroups of order provide an algebraic model for certain STS, which are collections of 3-element blocks on a -element set such that every unordered pair appears in exactly one block.[51] Specifically, a Steiner quasigroup is a totally symmetric idempotent quasigroup satisfying , , and ; its multiplication table encodes the triples via where is a block (with if ).[51] This equivalence holds isomorphically: STS exist precisely when or , and the quasigroup operation uniquely recovers the design, with subsystems corresponding to subquasigroups.[51] Such quasigroups are instrumental in enumerating and constructing large sets of STS, including extensions via idempotent commutative operations. Quasigroup-based error-correcting codes, often derived from Latin square transformations, offer robust mechanisms for detecting and correcting errors, including bursts.[52] These nonlinear codes exploit quasigroup operations to generate codewords with low autocorrelation, enabling correction of multiple errors in finite fields; for example, transformations using isotopic quasigroups yield codes with minimum distance proportional to the quasigroup order.[52] In burst error scenarios, cryptcodes constructed from quasigroups—such as random quasigroup-based encodings—facilitate fast decoding for image transmission over noisy channels, correcting contiguous error bursts by leveraging the bijective properties of the operations to recover original data with minimal redundancy.[53] Simulations show these codes achieve bit-error rates comparable to linear codes while resisting adversarial bursts, with performance scaling with quasigroup size.[54]Cryptography

Quasigroups find significant application in cryptography through quasigroup string transformations (QST), which leverage the non-associative binary operation to mix input strings in a nonlinear manner, providing a foundation for stream ciphers such as those proposed by Gligoroski et al. in 2004.[55] In these ciphers, QST processes plaintext sequences by iteratively applying the quasigroup operation, often combined with modular arithmetic over large primes, to generate keystreams that scramble data without relying on associative structures, thereby enhancing diffusion properties.[56] A notable example is the quasigroup encryptor described by Satti et al., which uses indexed quasigroup matrices to achieve high-entropy output even for repetitive inputs, suitable for symmetric stream encryption in resource-constrained environments.[57] Beyond stream ciphers, quasigroups underpin key agreement protocols and hash functions, often via their equivalence to Latin squares. For instance, public-key schemes like Xifrat employ restricted-commutative quasigroups to enable secure key exchange resistant to quantum attacks. Hash functions such as the Edon-R family utilize QST over quasigroups to compress inputs into fixed-length digests, ensuring collision resistance through the quasigroup's permutation properties derived from Latin square representations.[58] A comprehensive 2020 survey by Markovski highlights these uses, noting quasigroups' role in designing primitives for data integrity, digital signatures, and commitment schemes.[59] In 2024, a symmetric encryption scheme based on quasigroups with dynamic S-boxes was proposed, improving resistance to differential and linear cryptanalysis.[60] The non-associativity of quasigroups confers key advantages in cryptography, particularly resistance to linear cryptanalysis, as the lack of associative laws prevents straightforward linear approximations of the encryption function.[59] This property disrupts attacks that exploit linearity in group-based ciphers, making quasigroup operations ideal for substitution-permutation networks. Recent developments post-2020 integrate quasigroups into secure multi-party computation (MPC) protocols, enhancing privacy in distributed systems. For example, a 2025 MPC scheme for resilient coordination selects random elements from quasigroups to perform secure operations like multiplication and division, supporting applications in fault-tolerant environments such as blockchain networks.[61]Knot Theory

Quandles, defined as idempotent right-distributive quasigroups satisfying and for all , provide algebraic invariants for knots and links. Introduced by Joyce in 1982, quandle colorings assign elements of a quandle to knot arcs such that the operation respects crossings, distinguishing knots that groups cannot, such as the trefoil and figure-eight knot.[62] Quandle homology theories, developed in the 2000s, further enhance these invariants by capturing topological features, with applications in classifying knots up to concordance and studying link homologies.[63] This connection bridges quasigroup theory with low-dimensional topology, enabling computational tools for knot recognition and enumeration.Generalizations

Multiary Quasigroups

A multiary quasigroup, also known as an n-ary quasigroup for , is an algebraic structure consisting of a set equipped with an n-ary operation such that, for each position , the equation has a unique solution for any fixed .[64] This unique solvability condition generalizes the divisibility property of binary quasigroups to higher arities, ensuring that the operation allows for invertible "divisions" in each variable.[65] When , an n-ary quasigroup reduces precisely to a binary quasigroup, recovering the standard definition with left and right division.[64] For , it yields a ternary quasigroup, where the operation satisfies unique solvability in each of the three positions, often studied for its connections to geometric and combinatorial structures.[66] A key property is reducibility: an n-ary quasigroup is completely reducible if and only if it arises as an iterated binary group operation, such as in an abelian group, without needing parenthesization due to associativity.[64] Examples of multiary quasigroups frequently derive from iterative applications of binary operations. In particular, heaps provide a canonical construction of ternary quasigroups from binary groups or quasigroups: given a group with identity , the ternary operation defines a heap, which satisfies the unique solvability condition along with para-associativity and the heap axiom ensuring symmetry in certain divisions.[65] This structure captures "group-like" behavior without a specified identity, and its retracts (by fixing one variable) often yield binary quasigroups.[64] Recent advancements extend multiary quasigroups to hyperstructural settings through polyquasigroups and polylops, introduced in 2025. A polyquasigroup is a polygroupoid—a set with a hyperoperation producing subsets—equipped with hyperdivisions satisfying inclusion-based solvability conditions, such as for all , generalizing unique solvability to multi-valued outputs.[67] A polylop further requires a hyperidentity such that . Examples include finite sets like with explicitly tabulated hyperoperations forming polyquasigroups, and subsets thereof yielding polylops with identity 1, illustrating applications in hypergroup theory and generalized algebraic systems.[67]Quasigroupoids

A quasigroupoid is a generalization of a groupoid to non-associative settings, often defined in categorical terms as a magmoid where every span and cospan admits a unique factorization.[68] In algebraic terms, as studied in recent work, a quasigroupoid consists of a set (with ) equipped with partial binary multiplication and inversion, source map , and target map , such that multiplication is defined only when , with associativity holding whenever defined, every element having an inverse, and appropriate identity conditions via the maps.[69] This structure ensures local solvability properties akin to quasigroups but in a partial, directed setting. Quasigroupoids generalize quasigroups by relaxing the totality of the operation and incorporating categorical structure, allowing undefined products while maintaining divisibility where defined.[69] They encompass loopoids as a subclass, which are partial loops featuring a partial identity element satisfying whenever defined.[69] Examples of quasigroupoids include partial Latin squares, where the defined entries form a multiplication table satisfying the local quasigroup axioms, with undefined cells representing non-computable products.[70] They also appear in incomplete block designs, where the partial operation encodes incidence relations that are not specified for every pair of elements, yet satisfy solvability for defined blocks. Recent developments, published online in January 2025, introduced matrix representations for quasigroupoids, generalizing classical matrix models of groupoids to non-associative contexts by employing a parameterized family of quasigroups with source and target maps to define partial multiplications, such as when .[69] This approach proves that every connected quasigroupoid admits a non-canonical matrix representation (Theorem 5), facilitating the study of their embeddings and decompositions, including loopoids into pair groupoids and loops.[69]Enumeration

Small Quasigroups

The enumeration of quasigroups of small finite orders up to isomorphism reveals a rapid increase in complexity even for modest sizes. For order 1, there is a single trivial quasigroup on the singleton set, where the operation maps the unique element to itself. For order 2, there is exactly one quasigroup up to isomorphism, which coincides with the cyclic group of order 2 and thus is a loop. For order 3, there are five quasigroups up to isomorphism, of which one is a loop (the cyclic group of order 3). These five arise from the 12 Latin squares of order 3, classified into isomorphism classes via their Cayley tables. For order 4, there are 35 quasigroups up to isomorphism, including two loops (the cyclic group of order 4 and the Klein four-group). The classification into these 35 classes was obtained by enumerating the 576 Latin squares of order 4 and grouping them by quasigroup isomorphisms, which preserve the algebraic structure. The following table summarizes the counts of quasigroups and loops up to isomorphism for orders 1 through 4:| Order | Quasigroups | Loops |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 5 | 1 |

| 4 | 35 | 2 |

Small Loops

The enumeration and classification of small finite loops up to isomorphism focus on their structure as quasigroups with a two-sided identity element. For orders 1 through 3, there is precisely one loop of each order, and each is associative, coinciding with the cyclic group . Specifically, the loop of order 1 is the trivial group, that of order 2 is , and that of order 3 is .[72] For order 4, there are two non-isomorphic loops, both associative and thus groups: the cyclic group and the Klein four-group (also known as the dihedral group of order 4). It is a known result that all loops of order at most 4 are associative.[72][73] Non-associative loops first appear at order 5, where there are six loops up to isomorphism: one associative loop, the cyclic group , and five non-associative examples. The complete counts of loops up to isomorphism for small orders are summarized in the following table:| Order | Number of loops up to isomorphism |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 6 |