Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Recoilless rifle

View on Wikipedia

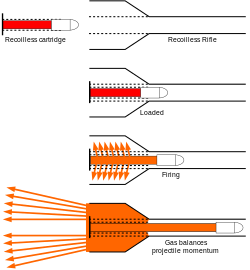

A recoilless rifle (rifled), recoilless launcher (smoothbore), recoilless rocket launcher,[1] or simply recoilless gun, sometimes abbreviated to "rr" or "RCL" (for ReCoilLess)[2] is a type of lightweight artillery system or man-portable launcher that is designed to eject some form of countermass such as propellant gas from the rear of the weapon at the moment of firing, creating forward thrust that counteracts most of the weapon's recoil. This allows for the elimination of much of the heavy and bulky recoil-counteracting equipment of a conventional cannon as well as a thinner-walled barrel, and thus the launch of a relatively large projectile from a platform that would not be capable of handling the weight or recoil of a conventional gun of the same size. Technically, only devices that use spin-stabilized projectiles fired from a rifled barrel are recoilless rifles, while smoothbore variants (which can be fin-stabilized or unstabilized) are recoilless guns. This distinction is often lost, and both are often called recoilless rifles.[3]

Though similar in appearance to a tube-based rocket launcher (since these also operate on a recoilless launch principle), the key difference is that recoilless weapons fire shells using a conventional smokeless propellant. While there are rocket-assisted rounds for recoilless weapons, they are still ejected from the barrel by the deflagration of a conventional propelling charge.

Because some projectile velocity is inevitably lost to the recoil compensation, recoilless rifles tend to have inferior range to traditional cannon, although with a far greater ease of transport, making them popular with paratroop, mountain warfare and special forces units, where portability is of particular concern, as well as with some light infantry and infantry fire support units. The greatly diminished recoil allows for devices that can be carried by individual infantrymen: heavier recoilless rifles are mounted on light tripods, wheeled light carriages, or small vehicles, and intended to be carried by crew of two to five. The largest versions retain enough bulk and recoil to be restricted to a towed mount or relatively heavy vehicle, but are still much lighter and more portable than cannon of the same scale. Such large systems have been replaced by guided anti-tank missiles in many armies.

History

[edit]

The earliest known example of a design for a gun based on recoilless principles was created by Leonardo da Vinci in the 15th or early 16th century.[4] This design was of a gun which fired projectiles in opposite directions, but there is no evidence any physical firearm based on the design was constructed at the time.

In 1879, a French patent was filed by Alfred Krupp for a recoilless gun.[5]

The first recoilless gun known to have been constructed was developed by Commander Cleland Davis of the US Navy, just prior to World War I. His design, named the Davis gun, connected two guns back-to-back, with the backwards-facing gun loaded with lead balls and grease of the same weight as the shell in the other gun. His idea was used experimentally by the British as an anti-Zeppelin and anti-submarine weapon mounted on a Handley Page O/100 bomber and intended to be installed on other aircraft.[6]

In the Soviet Union, the development of recoilless weapons ("Dinamo-Reaktivnaya Pushka" (DRP), roughly "dynamic reaction cannon") began in 1923. In the 1930s, many different types of weapons were built and tested with configurations ranging from 37 to 305 mm (1.5 to 12.0 in). Some of the smaller examples were tested in aircraft (Grigorovich I-Z and Tupolev I-12) and saw some limited production and service, but development was abandoned around 1938. The best-known of these early recoilless rifles was the Model 1935 76 mm DRP designed by Leonid Kurchevsky. A small number of these mounted on trucks saw combat in the Winter War. Two were captured by the Finns and tested; one example was given to the Germans in 1940.

The first recoilless gun to enter service in Germany was the 7.5 cm Leichtgeschütz 40 ("light gun" '40), a simple 75 mm smoothbore recoilless gun developed to give German airborne troops artillery and anti-tank support that could be parachuted into battle. The 7.5 cm LG 40 was found to be so useful during the invasion of Crete that Krupp and Rheinmetall set to work creating more powerful versions, respectively the 10.5 cm Leichtgeschütz 40 and 10.5 cm Leichtgeschütz 42. These weapons were loosely copied by the US Army. The Luftwaffe also showed great interest in aircraft-mounted recoilless weapons to allow their planes to attack tanks, fortified structures and ships. These included the unusual Düsenkanone 88, an 88 mm recoilless rifle fed by a 10-round rotary cylinder and with the exhaust vent angled upwards at 51 degrees to the barrel so it could pass through the host aircraft's fuselage rather than risking a rear-vented backblast damaging the tail, and the Sondergerät SG104 "Münchhausen", a gargantuan 14-inch (355.6 mm) weapon designed to be mounted under the fuselage of a Dornier Do 217. None of these systems proceeded beyond the prototype stage.[7]

The US did have a development program, and it is not clear to what extent the German designs were copied. These weapons remained fairly rare during the war, although the American M20 became increasingly common in 1945.

Postwar saw a great deal of interest in recoilless systems, as they potentially offered an effective replacement for the obsolete anti-tank rifle in infantry units (this was not the case for the US where no anti-tank rifle was adopted on a large scale).

During World War II, the Swedish military developed a shoulder-fired 20 mm device, the Pansarvärnsgevär m/42 (20 mm m/42); the British expressed their interest in it, but by that point the weapon, patterned after obsolete anti-tank rifles, was too weak to be effective against period tank armor. This system would form the basis of the much more successful Carl Gustav recoilless rifle postwar.

By the time of the Korean War, recoilless rifles were found throughout the US forces. The earliest American infantry recoilless rifles were the shoulder-fired 57 mm M18 and the tripod-mounted 75 mm M20, later followed by the 105 mm M27: the latter proved unreliable, too heavy, and too hard to aim.[8] Newer models replacing these were the 90 mm M67 and 106 mm M40 (which was actually 105 mm caliber, but designated otherwise to prevent accidental issue of incompatible M27 ammunition). In addition, the Davy Crockett, a muzzle-loaded recoilless launch system for tactical nuclear warheads intended to counteract Soviet tank units, was developed in the 1960s and deployed to American units in Germany.

The Soviet Union adopted a series of crew-served smoothbore recoilless guns in the 1950s and 1960s, specifically the 73 mm SPG-9, 82 mm B-10 and 107 mm B-11. All are found quite commonly around the world in the inventories of former Soviet client states, where they are usually used as anti-tank guns.

The British, whose efforts were led by Charles Dennistoun Burney, inventor of the Wallbuster HESH round, also developed recoilless designs. Burney demonstrated the technique with a recoilless 4-gauge shotgun. His "Burney Gun" was developed to fire the Wallbuster shell against the Atlantic Wall defences, but was not required in the D-Day landings of 1944. He went on to produce further designs, with two in particular created as anti-tank weapons. The Ordnance, RCL, 3.45 in could be fired off a man's shoulder or from a light tripod, and fired an 11 lb (5 kg) wallbuster shell to 1,000 yards. The larger Ordnance RCL. 3.7in fired a 22.2 lb (10 kg) wallbuster to 2,000 yd (1.8 km). Postwar work developed and deployed the BAT (Battalion, Anti Tank) series of recoilless rifles, culminating in the 120 mm L6 WOMBAT. This was too large to be transported by infantry and was usually towed by jeep. The weapon was aimed via a spotting rifle, a modified Bren Gun on the MOBAT and an American M8C spotting rifle on the WOMBAT: the latter fired a .50 BAT (12.7x77mm) point-detonating incendiary tracer round whose trajectory matched that of the main weapon. When tracer rounds hits were observed, the main gun was fired.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, SACLOS wire-guided missiles began to supplant recoilless rifles in the anti-tank role. While recoilless rifles and their ammunition retain several advantages such as being cheaper and easier to produce and maintain, as well as being able to be employed at extremely close range, as a guided missile typically has a significant deadzone before it can arm and begin to seek its target, missile systems tend to be lighter and more accurate, and are better suited to deployment of hollow-charge warheads. The large crew-served recoilless rifle started to disappear from first-rate armed forces, except in areas such as the Arctic, where thermal batteries used to provide after-launch power to wire-guided missiles like M47 Dragon and BGM-71 TOW would fail due to extremely low temperatures. The former 6th Light Infantry Division in Alaska used the M67 in its special weapons platoons, as did the Ranger Battalions and the US Army's Berlin Brigade. The last major use was the M50 Ontos, which mounted six M40 rifles on a light (9 short tons (8.2 t; 8.0 long tons)) tracked chassis. They were largely used in an anti-personnel role firing "beehive" flechette rounds. In 1970, the Ontos was removed from service and most were broken up. The M40, usually mounted on a jeep or technical, is still very common in conflict zones throughout the world, where it is used as a hard-hitting strike weapon in support of infantry.

Front-line recoilless weapons in the armies of modern industrialized nations are mostly man-portable devices such as the Carl Gustav, an 84 mm weapon. First introduced in 1948 and exported extensively since 1964, it is still in widespread use throughout the world today: a huge selection of special-purpose rounds are available for the system, and the current variant, known as the M4 or M3E1, is designed to be compatible with computerized optics and future "smart" ammunition. Many nations also use a weapon derived from the Carl Gustav, the one-shot AT4, which was originally developed in 1984 to fulfil an urgent requirement for an effective replacement for the M72 LAW after the failure of the FGR-17 Viper program the previous year. The ubiquitous RPG-7 is also technically a recoilless gun, since its rocket-powered projectile is launched using an explosive booster charge (even more so when firing the OG-7V anti-personnel round, which has no rocket motor), though it is usually not classified as one.

Design

[edit]

There are a number of principles under which a recoilless gun can operate, all involving the ejection of some kind of counter-mass from the rear of the gun tube to offset the force of the projectile being fired forward. The most basic method, and the first to be employed, is simply making a double-ended gun with a conventional sealed breech, which fires identical projectiles forwards and backwards. Such a system places enormous stress on its midpoint, is extremely cumbersome to reload, and has the highly undesirable effect of launching a projectile potentially just as deadly as the one launched at the enemy at a point behind the shooter where their allies may well be.

The most common system involves venting some portion of the weapon's propellant gas to the rear of the tube, in the same fashion as a rocket launcher. This creates a forward directed momentum which is nearly equal to the rearward momentum (recoil) imparted to the system by accelerating the projectile. The balance thus created does not leave much momentum to be imparted to the weapon's mounting or the gunner in the form of felt recoil. Since recoil has been mostly negated, a heavy and complex recoil damping mechanism is not necessary. Despite the name, it is rare for the forces to completely balance, and real-world recoilless rifles do recoil noticeably (with varying degrees of severity). Recoilless rifles will not function correctly if the venting system is damaged, blocked, or poorly maintained: in this state, the recoil-damping effect can be reduced or lost altogether, leading to dangerously powerful recoil. Conversely, if a projectile becomes lodged in the barrel for any reason, the entire weapon will be forced forward.

Recoilless rifle rounds for breech-loading reloadable systems resemble conventional cased ammunition, using a driving band to engage the rifled gun tube and spin-stabilize the projectile. The casing of a recoilless rifle round is often perforated to vent the propellant gases, which are then directed to the rear by an expansion chamber surrounding the weapon's breech. In the case of single-shot recoilless weapons such as the Panzerfaust or AT4, the device is externally almost identical in design to a single-shot rocket launcher: the key difference is that the launch tube is a gun that launches the projectile using a pre-loaded powder charge, not a hollow tube. Weapons of this type can either encase their projectile inside the disposable gun tube, or mount it on the muzzle: the latter allows the launching of an above-caliber projectile. Like single shot rocket launchers, the need to only survive a single firing means that single-shot recoilless weapons can be made from relatively flimsy and therefore very light materials, such as fiberglass. Recoilless gun launch systems are often used to provide the initial thrust for man-portable weapons firing rocket-powered projectiles: examples include the RPG-7, Panzerfaust 3 and MATADOR.

Since venting propellant gases to the rear can be dangerous in confined spaces, some recoilless guns use a combination of a countershot and captive piston propelling cartridge design to avoid both recoil and backblast. The Armbrust "cartridge," for example, contains the propellant charge inside a double-ended piston assembly, with the projectile in front, and an equal countermass of shredded plastic to the rear. On firing, the propellant expands rapidly, pushing the pistons outward. This pushes the projectile forwards towards the target and the countermass backwards providing the recoilless effect. The shredded plastic countermass is quickly slowed by air resistance and is harmless at a distance more than a few feet from the rear of the barrel. The two ends of the piston assembly are captured at the ends of the barrel, by which point the propellant gas has expanded and cooled enough that there is no threat of explosion. Other countermass materials that have been used include inert powders and liquids.

Civilian use

[edit]

Obsolete 75 mm M20 and 105 mm M27 recoilless rifles were used by the U.S. National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service as a system for triggering controlled avalanches at a safe distance, from the early 1950s until the U.S. military's inventory of surplus ammunition for these weapons was exhausted in the 1990s. They were then replaced with M40 106 mm recoilless rifles, but following a catastrophic in-bore ammunition explosion that killed one of the five-man gun crew at Alpine Meadows Ski Resort, California, in 1995 and two further in-bore explosions at Mammoth Mountain, California, within thirteen days of each other in December 2002, all such guns were removed from use and replaced with surplus 105 mm howitzers.[9]

See also

[edit]- List of recoilless rifles

- List of MANPATS (Man Portable Anti-Tank System)

- Newton's laws of motion

- Rocket-assisted projectile

- Rocket-propelled grenade

- List of rocket launchers

References

[edit]- ^ "Changing the fight: Marine Corps fields new rocket system to infantry Marines".

- ^ "Recoilless Weapons" (PDF). Small Arms Survey Research Notes. Vol. 55. December 2015. pp. 1–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-14. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ^ Julio, S. (April 1953), Las Armas Modernas de Infantería

- ^ Olcer, Nuri Y.; Lévin, Sam (1976). Recoilless rifle weapon systems.

- ^ Description des machines et procédés pour lesquels des brevets d'invention ont été pris sous le régime de la loi du 5 Juillet 1844: N.S. 33. 1879, 2 (in French). 1885.

- ^ DeMarco, F. (2017). Improvised Home-Built Recoilless Launchers. www.paladin-press.com. p. 3. ISBN 978-087364-830-1.

- ^ Dieter Hedwig; Heinz Rode (2002). Luftwaffe Secret Projects. Motorbuch Verlag. pp. 259–261.

- ^ Hutton, Robin (2014). Sgt. Reckless: America's War Horse. Regnery History. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-62157-263-3.

- ^ "United States Military Artillery for Avalanche Control Program:A Brief History in Time" (PDF). USDA Forest Service National Avalanche Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

External links

[edit] Media related to Recoilless rifles at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Recoilless rifles at Wikimedia Commons- US3738219A - Recoilless firearm and cartridge therefor

- US3838622A - Recoilless firearm and cartridge therefor