Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Euclidean tilings by convex regular polygons

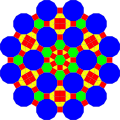

View on Wikipedia A regular tiling has one type of regular face. |

A semiregular or uniform tiling has one type of vertex, but two or more types of faces. |

A k-uniform tiling has k types of vertices, and two or more types of regular faces. |

A non-edge-to-edge tiling can have different-sized regular faces. |

Euclidean plane tilings by convex regular polygons have been widely used since antiquity. The first systematic mathematical treatment was that of Kepler in his Harmonice Mundi (Latin: The Harmony of the World, 1619).

Notation of Euclidean tilings

[edit]Euclidean tilings are usually named after Cundy & Rollett’s notation.[1] This notation represents (i) the number of vertices, (ii) the number of polygons around each vertex (arranged clockwise) and (iii) the number of sides to each of those polygons. For example: 36; 36; 34.6, tells us there are 3 vertices with 2 different vertex types, so this tiling would be classed as a "3-uniform (2-vertex types)" tiling. Broken down, 36; 36 (both of different transitivity class), or (36)2, tells us that there are 2 vertices (denoted by the superscript 2), each with 6 equilateral 3-sided polygons (triangles). With a final vertex 34.6, 4 more contiguous equilateral triangles and a single regular hexagon.

However, this notation has two main problems related to ambiguous conformation and uniqueness [2] First, when it comes to k-uniform tilings, the notation does not explain the relationships between the vertices. This makes it impossible to generate a covered plane given the notation alone. And second, some tessellations have the same nomenclature, they are very similar but it can be noticed that the relative positions of the hexagons are different. Therefore, the second problem is that this nomenclature is not unique for each tessellation.

In order to solve those problems, GomJau-Hogg's notation [3] is a slightly modified version of the research and notation presented in 2012,[2] about the generation and nomenclature of tessellations and double-layer grids. Antwerp v3.0,[4] a free online application, allows for the infinite generation of regular polygon tilings through a set of shape placement stages and iterative rotation and reflection operations, obtained directly from the GomJau-Hogg's notation.

Regular tilings

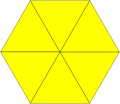

[edit]Following Grünbaum and Shephard (section 1.3), a tiling is said to be regular if the symmetry group of the tiling acts transitively on the flags of the tiling, where a flag is a triple consisting of a mutually incident vertex, edge and tile of the tiling. This means that, for every pair of flags, there is a symmetry operation mapping the first flag to the second. This is equivalent to the tiling being an edge-to-edge tiling by congruent regular polygons. There must be six equilateral triangles, four squares or three regular hexagons at a vertex, yielding the three regular tessellations.

| p6m, *632 | p4m, *442 | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

C&R: 36 GJ-H: 3/m30/r(h2) (t = 1, e = 1) |

C&R: 63 GJ-H: 6/m30/r(h1) (t = 1, e = 1) |

C&R: 44 GJ-H: 4/m45/r(h1) (t = 1, e = 1) |

C&R: Cundy & Rollet's notation

GJ-H: Notation of GomJau-Hogg

Archimedean, uniform or semiregular tilings

[edit]Vertex-transitivity means that for every pair of vertices there is a symmetry operation mapping the first vertex to the second.[5]

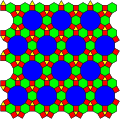

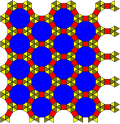

If the requirement of flag-transitivity is relaxed to one of vertex-transitivity, while the condition that the tiling is edge-to-edge is kept, there are eight additional tilings possible, known as Archimedean, uniform or semiregular tilings. Note that there are two mirror image (enantiomorphic or chiral) forms of 34.6 (snub hexagonal) tiling, only one of which is shown in the following table. All other regular and semiregular tilings are achiral.

| p6m, *632 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

C&R: 3.122 GJ-H: 12-3/m30/r(h3) (t = 2, e = 2) t{6,3} |

C&R: 3.4.6.4 GJ-H: 6-4-3/m30/r(c2) (t = 3, e = 2) rr{3,6} |

C&R: 4.6.12 GJ-H: 12-6,4/m30/r(c2) (t = 3, e = 3) tr{3,6} |

C&R: (3.6)2 GJ-H: 6-3-6/m30/r(v4) (t = 2, e = 1) r{6,3} | ||

C&R: 4.82 GJ-H: 8-4/m90/r(h4) (t = 2, e = 2) t{4,4} |

C&R: 32.4.3.4 GJ-H: 4-3-3,4/r90/r(h2) (t = 2, e = 2) s{4,4} |

C&R: 33.42 GJ-H: 4-3/m90/r(h2) (t = 2, e = 3) {3,6}:e |

C&R: 34.6 GJ-H: 6-3-3/r60/r(h5) (t = 3, e = 3) sr{3,6} | ||

C&R: Cundy & Rollet's notation

GJ-H: Notation of GomJau-Hogg

Grünbaum and Shephard distinguish the description of these tilings as Archimedean as referring only to the local property of the arrangement of tiles around each vertex being the same, and that as uniform as referring to the global property of vertex-transitivity. Though these yield the same set of tilings in the plane, in other spaces there are Archimedean tilings which are not uniform.

Plane-vertex tilings

[edit]There are 17 combinations of regular convex polygons that form 21 types of plane-vertex tilings.[6][7] Polygons in these meet at a point with no gap or overlap. Listing by their vertex figures, one has 6 polygons, three have 5 polygons, seven have 4 polygons, and ten have 3 polygons.[8]

Three of them can make regular tilings (63, 44, 36), and eight more can make semiregular or archimedean tilings, (3.12.12, 4.6.12, 4.8.8, (3.6)2, 3.4.6.4, 3.3.4.3.4, 3.3.3.4.4, 3.3.3.3.6). Four of them can exist in higher k-uniform tilings (3.3.4.12, 3.4.3.12, 3.3.6.6, 3.4.4.6), while six can not be used to completely tile the plane by regular polygons with no gaps or overlaps - they only tessellate space entirely when irregular polygons are included (3.7.42, 3.8.24, 3.9.18, 3.10.15, 4.5.20, 5.5.10).[9]

| 6 | 36 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 3.3.4.3.4 |

3.3.3.4.4 |

3.3.3.3.6 | |||||||

| 4 | 3.3.4.12 |

3.4.3.12 |

3.3.6.6 |

(3.6)2 |

3.4.4.6 |

3.4.6.4 |

44 | |||

| 3 |  3.7.42 |

3.8.24 |

3.9.18 |

3.10.15 |

3.12.12 |

4.5.20 |

4.6.12 |

4.8.8 |

5.5.10 |

63 |

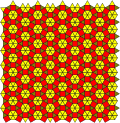

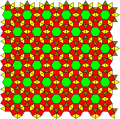

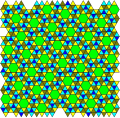

k-uniform tilings

[edit]Such periodic tilings may be classified by the number of orbits of vertices, edges and tiles. If there are k orbits of vertices, a tiling is known as k-uniform or k-isogonal; if there are t orbits of tiles, as t-isohedral; if there are e orbits of edges, as e-isotoxal.

k-uniform tilings with the same vertex figures can be further identified by their wallpaper group symmetry.

1-uniform tilings include 3 regular tilings, and 8 semiregular ones, with 2 or more types of regular polygon faces. There are 20 2-uniform tilings, 61 3-uniform tilings, 151 4-uniform tilings, 332 5-uniform tilings and 673 6-uniform tilings. Each can be grouped by the number m of distinct vertex figures, which are also called m-Archimedean tilings.[10]

Finally, if the number of types of vertices is the same as the uniformity (m = k below), then the tiling is said to be Krotenheerdt. In general, the uniformity is greater than or equal to the number of types of vertices (m ≥ k), as different types of vertices necessarily have different orbits, but not vice versa. Setting m = n = k, there are 11 such tilings for n = 1; 20 such tilings for n = 2; 39 such tilings for n = 3; 33 such tilings for n = 4; 15 such tilings for n = 5; 10 such tilings for n = 6; and 7 such tilings for n = 7.

Below is an example of a 3-unifom tiling:

by sides, yellow triangles, red squares (by polygons) |

by 4-isohedral positions, 3 shaded colors of triangles (by orbits) |

| m-Archimedean | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ≥ 15 | Total | ||

| k-uniform | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 2 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | |

| 3 | 0 | 22 | 39 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 61 | |

| 4 | 0 | 33 | 85 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 151 | |

| 5 | 0 | 74 | 149 | 94 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 332 | |

| 6 | 0 | 100 | 284 | 187 | 92 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 673 | |

| 7 | 0 | 175 | 572 | 426 | 218 | 74 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1472 | |

| 8 | 0 | 298 | 1037 | 795 | 537 | 203 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2850 | |

| 9 | 0 | 424 | 1992 | 1608 | 1278 | 570 | 80 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5960 | |

| 10 | 0 | 663 | 3772 | 2979 | 2745 | 1468 | 212 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11866 | |

| 11 | 0 | 1086 | 7171 | 5798 | 5993 | 3711 | 647 | 52 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24459 | |

| 12 | 0 | 1607 | 13762 | 11006 | 12309 | 9230 | 1736 | 129 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49794 | |

| 13 | 0 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 103082 | |

| 14 | 0 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ? | |

| ≥ 15 | 0 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 0 | ? | |

| Total | 11 | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | ∞ | 0 | ∞ | |

2-uniform tilings

[edit]There are twenty (20) 2-uniform tilings of the Euclidean plane. (also called 2-isogonal tilings or demiregular tilings) [5]: 62-67 [14][15] Vertex types are listed for each. If two tilings share the same two vertex types, they are given subscripts 1,2.

| p6m, *632 | p4m, *442 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[36; 32.4.3.4] 3-4-3/m30/r(c3) (t = 3, e = 3) |

[3.4.6.4; 32.4.3.4] 6-4-3,3/m30/r(h1) (t = 4, e = 4) |

[3.4.6.4; 33.42] 6-4-3-3/m30/r(h5) (t = 4, e = 4) |

[3.4.6.4; 3.42.6] 6-4-3,4-6/m30/r(c4) (t = 5, e = 5) |

[4.6.12; 3.4.6.4] 12-4,6-3/m30/r(c3) (t = 4, e = 4) |

[36; 32.4.12] 12-3,4-3/m30/r(c3) (t = 4, e = 4) |

[3.12.12; 3.4.3.12] 12-0,3,3-0,4/m45/m(h1) (t = 3, e = 3) |

| p6m, *632 | p6, 632 | p6, 632 | cmm, 2*22 | pmm, *2222 | cmm, 2*22 | pmm, *2222 |

[36; 32.62] 3-6/m30/r(c2) (t = 2, e = 3) |

[36; 34.6]1 6-3,3-3/m30/r(h1) (t = 3, e = 3) |

[36; 34.6]2 6-3-3,3-3/r60/r(h8) (t = 5, e = 7) |

[32.62; 34.6] 6-3/m90/r(h1) (t = 2, e = 4) |

[3.6.3.6; 32.62] 6-3,6/m90/r(h3) (t = 2, e = 3) |

[3.42.6; 3.6.3.6]2 6-3,4-6-3,4-6,4/m90/r(c6) (t = 3, e = 4) |

[3.42.6; 3.6.3.6]1 6-3,4/m90/r(h4) (t = 4, e = 4) |

| p4g, 4*2 | pgg, 22× | cmm, 2*22 | cmm, 2*22 | pmm, *2222 | cmm, 2*22 | |

[33.42; 32.4.3.4]1 4-3,3-4,3/r90/m(h3) (t = 4, e = 5) |

[33.42; 32.4.3.4]2 4-3,3,3-4,3/r(c2)/r(h13)/r(h45) (t = 3, e = 6) |

[44; 33.42]1 4-3/m(h4)/m(h3)/r(h2) (t = 2, e = 4) |

[44; 33.42]2 4-4-3-3/m90/r(h3) (t = 3, e = 5) |

[36; 33.42]1 4-3,4-3,3/m90/r(h3) (t = 3, e = 4) |

[36; 33.42]2 4-3-3-3/m90/r(h7)/r(h5) (t = 4, e = 5) | |

Higher k-uniform tilings

[edit]k-uniform tilings have been enumerated up to 6. There are 673 6-uniform tilings of the Euclidean plane. Brian Galebach's search reproduced Krotenheerdt's list of 10 6-uniform tilings with 6 distinct vertex types, as well as finding 92 of them with 5 vertex types, 187 of them with 4 vertex types, 284 of them with 3 vertex types, and 100 with 2 vertex types.

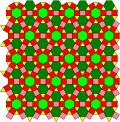

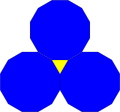

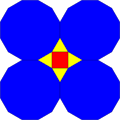

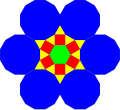

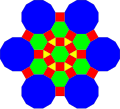

Fractalizing k-uniform tilings

[edit]There are many ways of generating new k-uniform tilings from old k-uniform tilings. For example, notice that the 2-uniform [3.12.12; 3.4.3.12] tiling has a square lattice, the 4(3-1)-uniform [343.12; (3.122)3] tiling has a snub square lattice, and the 5(3-1-1)-uniform [334.12; 343.12; (3.12.12)3] tiling has an elongated triangular lattice. These higher-order uniform tilings use the same lattice but possess greater complexity. The fractalizing basis for theses tilings is as follows:[16]

| Triangle | Square | Hexagon | Dissected Dodecagon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape |  |

|

|

|

| Fractalizing |  |

|

|

|

The side lengths are dilated by a factor of .

This can similarly be done with the truncated trihexagonal tiling as a basis, with corresponding dilation of .

| Triangle | Square | Hexagon | Dissected Dodecagon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape |  |

|

|

|

| Fractalizing |  |

|

|

|

Fractalizing examples

[edit]| Truncated Hexagonal Tiling | Truncated Trihexagonal Tiling | |

|---|---|---|

| Fractalizing |  |

|

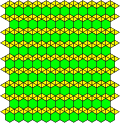

Tilings that are not edge-to-edge

[edit]Convex regular polygons can also form plane tilings that are not edge-to-edge. Such tilings can be considered edge-to-edge as nonregular polygons with adjacent colinear edges.

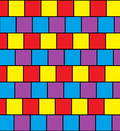

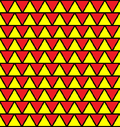

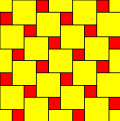

There are seven families of isogonal figures, each family having a real-valued parameter determining the overlap between sides of adjacent tiles or the ratio between the edge lengths of different tiles. Two of the families are generated from shifted square, either progressive or zig-zagging positions. Grünbaum and Shephard call these tilings uniform although it contradicts Coxeter's definition for uniformity which requires edge-to-edge regular polygons.[17] Such isogonal tilings are actually topologically identical to the uniform tilings, with different geometric proportions.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rows of squares with horizontal offsets |

Rows of triangles with horizontal offsets |

A tiling by squares |

Three hexagons surround each triangle |

Six triangles surround every hexagon. |

Three size triangles | |

| cmm (2*22) | p2 (2222) | cmm (2*22) | p4m (*442) | p6 (632) | p3 (333) | |

| Hexagonal tiling | Square tiling | Truncated square tiling | Truncated hexagonal tiling | Hexagonal tiling | Trihexagonal tiling | |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cundy, H.M.; Rollett, A.P. (1981). Mathematical Models;. Stradbroke (UK): Tarquin Publications.

- ^ a b Gomez-Jauregui, Valentin al.; Otero, Cesar; et al. (2012). "Generation and Nomenclature of Tessellations and Double-Layer Grids". Journal of Structural Engineering. 138 (7): 843–852. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)ST.1943-541X.0000532. hdl:10902/5869.

- ^ Gomez-Jauregui, Valentin; Hogg, Harrison; et al. (2021). "GomJau-Hogg's Notation for Automatic Generation of k-Uniform Tessellations with ANTWERP v3.0". Symmetry. 13 (12): 2376. Bibcode:2021Symm...13.2376G. doi:10.3390/sym13122376. hdl:10902/23907.

- ^ Hogg, Harrison; Gomez-Jauregui, Valentin. < "Antwerp 3.0".

- ^ a b Critchlow, K. (1969). Order in Space: A Design Source Book. London: Thames and Hudson. pp. 60–61.

- ^ Dallas, Elmslie William (1855), The Elements of Plane Practical Geometry, Etc, John W. Parker & Son, p. 134

- ^ Tilings and patterns, Figure 2.1.1, p.60

- ^ Tilings and patterns, p.58-69

- ^ "Pentagon-Decagon Packing". American Mathematical Society. AMS. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ^ k-uniform tilings by regular polygons Archived 2015-06-30 at the Wayback Machine Nils Lenngren, 2009

- ^ "n-Uniform Tilings". probabilitysports.com. Retrieved 2019-06-21.

- ^ Sloane, N. J. A. (ed.). "Sequence A068599 (Number of n-uniform tilings.)". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation. Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- ^ "Enumeration of n-uniform k-Archimedean tilings". zenorogue.github.io/tes-catalog/?c=. Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ Tilings and patterns, Grünbaum and Shephard 1986, pp. 65-67

- ^ "In Search of Demiregular Tilings" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-07. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- ^ Chavey, Darrah (2014). "TILINGS BY REGULAR POLYGONS III: DODECAGON-DENSE TILINGS". Symmetry-Culture and Science. 25 (3): 193–210. S2CID 33928615.

- ^ "Tilings by regular polygons" (PDF). p. 236. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03.

- Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, Geoffrey C. (1977). "Tilings by regular polygons". Math. Mag. 50 (5): 227–247. doi:10.2307/2689529. JSTOR 2689529.

- Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, G. C. (1978). "The ninety-one types of isogonal tilings in the plane". Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 252: 335–353. doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-1978-0496813-3. MR 0496813.

- Debroey, I.; Landuyt, F. (1981). "Equitransitive edge-to-edge tilings". Geometriae Dedicata. 11 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1007/BF00183189. S2CID 122636363.

- Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, G. C. (1987). Tilings and Patterns. W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-1193-1.

- Ren, Ding; Reay, John R. (1987). "The boundary characteristic and Pick's theorem in the Archimedean planar tilings". J. Comb. Theory A. 44 (1): 110–119. doi:10.1016/0097-3165(87)90063-X.

- Chavey, D. (1989). "Tilings by Regular Polygons—II: A Catalog of Tilings". Computers & Mathematics with Applications. 17: 147–165. doi:10.1016/0898-1221(89)90156-9.

- Order in Space: A design source book, Keith Critchlow, 1970 ISBN 978-0-670-52830-1

- Sommerville, Duncan MacLaren Young (1958). An Introduction to the Geometry of n Dimensions. Dover Publications. Chapter X: The Regular Polytopes

- Préa, P. (1997). "Distance sequences and percolation thresholds in Archimedean Tilings". Mathl. Comput. Modelling. 26 (8–10): 317–320. doi:10.1016/S0895-7177(97)00216-1.

- Kovic, Jurij (2011). "Symmetry-type graphs of Platonic and Archimedean solids". Math. Commun. 16 (2): 491–507.

- Pellicer, Daniel; Williams, Gordon (2012). "Minimal Covers of the Archimedean Tilings, Part 1". The Electronic Journal of Combinatorics. 19 (3): #P6. doi:10.37236/2512.

- Dale Seymour and Jill Britton, Introduction to Tessellations, 1989, ISBN 978-0866514613, pp. 50–57

External links

[edit]Euclidean and general tiling links:

- n-uniform tilings, Brian Galebach

- Dutch, Steve. "Uniform Tilings". Archived from the original on 2006-09-09. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- Mitchell, K. "Semi-Regular Tilings". Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Tessellation". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Semiregular tessellation". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Demiregular tessellation". MathWorld.

Euclidean tilings by convex regular polygons

View on GrokipediaFundamentals and Notation

Notation for Euclidean tilings

In Euclidean tilings by convex regular polygons, the arrangement of polygons meeting at each vertex is described using a symbolic notation known as the vertex configuration or Cundy-Rollett symbol. This system, introduced by H. Martyn Cundy and A. P. Rollett in their 1961 book Mathematical Models, represents the cyclic sequence of polygons around a vertex as a series of integers separated by dots, where each integer denotes the number of sides of the adjacent polygon (e.g., 3 for a triangle, 4 for a square).[4] For repeated identical polygons, a superscript indicates the count, such as 3^6 for six triangles. The sequence is arranged in counterclockwise order starting from a reference point, often chosen to begin with the smallest integer for standardization, ensuring the notation captures the full 360-degree cycle around the vertex.[4] The notation adheres to specific rules to maintain consistency and uniqueness. Polygons are listed in the order they meet at the vertex, reflecting the tiling's local geometry, and the arrangement must be cyclic, meaning rotations of the sequence represent the same configuration. To avoid redundancy, the sequence is normalized by rotating it to start with the lowest number and, if ties occur, selecting the lexicographically smallest variant among rotations and reflections. Critically, the sum of the interior angles of the polygons at the vertex must equal exactly 360 degrees to ensure a Euclidean (flat) tiling without gaps or overlaps, a condition derived from the interior angle formula for a regular n-gon: ((n-2)/n) × 180 degrees.[4] This notation applies primarily to uniform tilings, where all vertices are congruent, but can extend to describe vertex types in more general tilings. This symbolic system originated in the mid-20th century amid efforts to classify symmetric tilings, building on foundational work by H. S. M. Coxeter and others who explored regular polytopes and honeycombs in the 1940s and 1950s. Coxeter's analyses in works like Regular Polytopes (1948, third edition 1973) laid groundwork for systematic descriptions of vertex figures, influencing the adoption of integer sequences for plane tilings. Cundy and Rollett formalized and popularized the dotted notation specifically for educational models of tilings and polyhedra, making it a standard in geometric literature.[4] The 11 uniform Euclidean tilings—comprising three regular and eight Archimedean—illustrate the notation's application. Each has a unique vertex configuration satisfying the angle sum condition.| Tiling Type | Notation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Regular triangular | 3^6 | Six equilateral triangles meet at each vertex. |

| Regular square | 4^4 | Four squares meet at each vertex. |

| Regular hexagonal | 6^3 | Three regular hexagons meet at each vertex. |

| Truncated square | 4.8.8 | One square and two octagons meet at each vertex. |

| Truncated hexagonal | 3.12.12 | One triangle and two dodecagons meet at each vertex. |

| Rhombitrihexagonal | 3.4.6.4 | Alternating triangles, squares, and hexagons meet at each vertex. |

| Snub hexagonal | 3.3.3.3.6 | Four triangles and one hexagon meet at each vertex. |

| Trihexagonal | 3.6.3.6 | Alternating triangles and hexagons meet at each vertex. |

| Snub square | 3.3.4.3.4 | Three triangles and two squares meet at each vertex. |

| Elongated triangular | 3.3.3.4.4 | Three triangles and two squares meet at each vertex. |

| Truncated trihexagonal | 4.6.12 | One square, one hexagon, and one dodecagon meet at each vertex. |