Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hexagon

View on Wikipedia| Regular hexagon | |

|---|---|

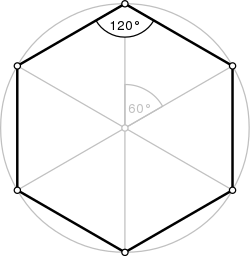

A regular hexagon | |

| Type | Regular polygon |

| Edges and vertices | 6 |

| Schläfli symbol | {6}, t{3} |

| Coxeter–Dynkin diagrams | |

| Symmetry group | Dihedral (D6), order 2×6 |

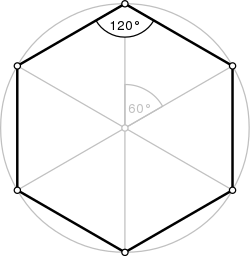

| Internal angle (degrees) | 120° |

| Properties | Convex, cyclic, equilateral, isogonal, isotoxal |

| Dual polygon | Self |

In geometry, a hexagon (from Greek ἕξ, hex, meaning "six", and γωνία, gonía, meaning "corner, angle") is a six-sided polygon.[1] The total of the internal angles of any simple (non-self-intersecting) hexagon is 720°.

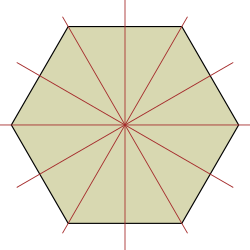

Regular hexagon

[edit]A regular hexagon is defined as a hexagon that is both equilateral and equiangular. In other words, a hexagon is said to be regular if the edges are all equal in length, and each of its internal angle is equal to 120°. The Schläfli symbol denotes this polygon as .[2] However, the regular hexagon can also be considered as the cutting off the vertices of an equilateral triangle, which can also be denoted as .

A regular hexagon is bicentric, meaning that it is both cyclic (has a circumscribed circle) and tangential (has an inscribed circle). The common length of the sides equals the radius of the circumscribed circle or circumcircle, which equals times the apothem (radius of the inscribed circle).

Measurement

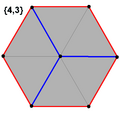

[edit]The longest diagonals of a regular hexagon, connecting diametrically opposite vertices, are twice the length of one side. From this it can be seen that a triangle with a vertex at the center of the regular hexagon and sharing one side with the hexagon is equilateral, and that the regular hexagon can be partitioned into six equilateral triangles.

The maximal diameter (which corresponds to the long diagonal of the hexagon), D, is twice the maximal radius or circumradius, R, which equals the side length, t. The minimal diameter or the diameter of the inscribed circle (separation of parallel sides, flat-to-flat distance, short diagonal or height when resting on a flat base), d, is twice the minimal radius or inradius, r. The maxima and minima are related by the same factor:

- and, similarly,

The area of a regular hexagon

For any regular polygon, the area can also be expressed in terms of the apothem a and the perimeter p. For the regular hexagon these are given by a = r, and p, so

The regular hexagon fills the fraction of its circumscribed circle.

If a regular hexagon has successive vertices A, B, C, D, E, F and if P is any point on the circumcircle between B and C, then PE + PF = PA + PB + PC + PD.

It follows from the ratio of circumradius to inradius that the height-to-width ratio of a regular hexagon is 1:1.1547005; that is, a hexagon with a long diagonal of 1.0000000 will have a distance of 0.8660254 or cos(30°) between parallel sides.

Point in plane

[edit]For an arbitrary point in the plane of a regular hexagon with circumradius , whose distances to the centroid of the regular hexagon and its six vertices are and respectively, we have[3]

If are the distances from the vertices of a regular hexagon to any point on its circumcircle, then [3]

Construction

[edit]Symmetry

[edit]

A regular hexagon has six rotational symmetries (rotational symmetry of order six) and six reflection symmetries (six lines of symmetry), making up the dihedral group D6.[4] There are 16 subgroups. There are 8 up to isomorphism: itself (D6), 2 dihedral: (D3, D2), 4 cyclic: (Z6, Z3, Z2, Z1) and the trivial (e)

These symmetries express nine distinct symmetries of a regular hexagon. John Conway labels these by a letter and group order.[5] r12 is full symmetry, and a1 is no symmetry. p6, an isogonal hexagon constructed by three mirrors can alternate long and short edges, and d6, an isotoxal hexagon constructed with equal edge lengths, but vertices alternating two different internal angles. These two forms are duals of each other and have half the symmetry order of the regular hexagon. The i4 forms are regular hexagons flattened or stretched along one symmetry direction. It can be seen as an elongated rhombus, while d2 and p2 can be seen as horizontally and vertically elongated kites. g2 hexagons, with opposite sides parallel are also called hexagonal parallelogons.

Each subgroup symmetry allows one or more degrees of freedom for irregular forms. Only the g6 subgroup has no degrees of freedom but can be seen as directed edges.

Hexagons of symmetry g2, i4, and r12, as parallelogons can tessellate the Euclidean plane by translation. Other hexagon shapes can tile the plane with different orientations.

| p6m (*632) | cmm (2*22) | p2 (2222) | p31m (3*3) | pmg (22*) | pg (××) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

r12 |

i4 |

g2 |

d2 |

d2 |

p2 |

a1 |

| Dih6 | Dih2 | Z2 | Dih1 | Z1 | ||

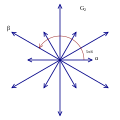

A2 group roots |

G2 group roots |

The 6 roots of the simple Lie group A2, represented by a Dynkin diagram ![]()

![]()

![]() , are in a regular hexagonal pattern. The two simple roots have a 120° angle between them.

, are in a regular hexagonal pattern. The two simple roots have a 120° angle between them.

The 12 roots of the Exceptional Lie group G2, represented by a Dynkin diagram ![]()

![]()

![]() are also in a hexagonal pattern. The two simple roots of two lengths have a 150° angle between them.

are also in a hexagonal pattern. The two simple roots of two lengths have a 150° angle between them.

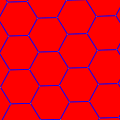

Tessellations

[edit]Like squares and equilateral triangles, regular hexagons fit together without any gaps to tile the plane (three hexagons meeting at every vertex), and so are useful for constructing tessellations.[6] The cells of a beehive honeycomb are hexagonal for this reason and because the shape makes efficient use of space and building materials. The Voronoi diagram of a regular triangular lattice is the honeycomb tessellation of hexagons.

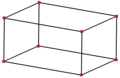

Dissection

[edit]| 6-cube projection | 12 rhomb dissection | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Coxeter states that every zonogon (a 2m-gon whose opposite sides are parallel and of equal length) can be dissected into 1⁄2m(m − 1) parallelograms.[7] In particular this is true for regular polygons with evenly many sides, in which case the parallelograms are all rhombi. This decomposition of a regular hexagon is based on a Petrie polygon projection of a cube, with 3 of 6 square faces. Other parallelogons and projective directions of the cube are dissected within rectangular cuboids.

| Dissection of hexagons into three rhombs and parallelograms | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D | Rhombs | Parallelograms | |||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||

| Regular {6} | Hexagonal parallelogons | ||||||||||

| 3D | Square faces | Rectangular faces | |||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||

| Cube | Rectangular cuboid | ||||||||||

Related polygons and tilings

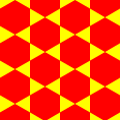

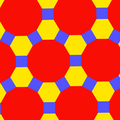

[edit]A regular hexagon has Schläfli symbol {6}. A regular hexagon is a part of the regular hexagonal tiling, {6,3}, with three hexagonal faces around each vertex.

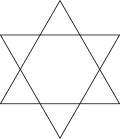

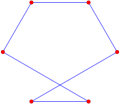

A regular hexagon can also be created as a truncated equilateral triangle, with Schläfli symbol t{3}. Seen with two types (colors) of edges, this form only has D3 symmetry.

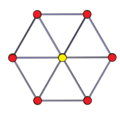

A truncated hexagon, t{6}, is a dodecagon, {12}, alternating two types (colors) of edges. An alternated hexagon, h{6}, is an equilateral triangle, {3}. A regular hexagon can be stellated with equilateral triangles on its edges, creating a hexagram. A regular hexagon can be dissected into six equilateral triangles by adding a center point. This pattern repeats within the regular triangular tiling.

A regular hexagon can be extended into a regular dodecagon by adding alternating squares and equilateral triangles around it. This pattern repeats within the rhombitrihexagonal tiling.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Regular {6} |

Truncated t{3} = {6} |

Hypertruncated triangles | Stellated Star figure 2{3} |

Truncated t{6} = {12} |

Alternated h{6} = {3} | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Crossed hexagon |

A concave hexagon | A self-intersecting hexagon (star polygon) | Extended Central {6} in {12} |

A skew hexagon, within cube | Dissected {6} | projection octahedron |

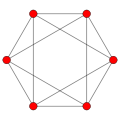

Complete graph |

|---|

Self-crossing hexagons

[edit]There are six self-crossing hexagons with the vertex arrangement of the regular hexagon:

| Dih2 | Dih1 | Dih3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Figure-eight |

Center-flip |

Unicursal |

Fish-tail |

Double-tail |

Triple-tail |

Hexagonal structures

[edit]

From bees' honeycombs to the Giant's Causeway, hexagonal patterns are prevalent in nature due to their efficiency. In a hexagonal grid each line is as short as it can possibly be if a large area is to be filled with the fewest hexagons. This means that honeycombs require less wax to construct and gain much strength under compression.

Irregular hexagons with parallel opposite edges are called parallelogons and can also tile the plane by translation. In three dimensions, hexagonal prisms with parallel opposite faces are called parallelohedrons and these can tessellate 3-space by translation.

| Form | Hexagonal tiling | Hexagonal prismatic honeycomb |

|---|---|---|

| Regular |

|

|

| Parallelogonal |

|

|

Tesselations by hexagons

[edit]In addition to the regular hexagon, which determines a unique tessellation of the plane, any irregular hexagon which satisfies the Conway criterion will tile the plane.

Hexagon inscribed in a conic section

[edit]Pascal's theorem (also known as the "Hexagrammum Mysticum Theorem") states that if an arbitrary hexagon is inscribed in any conic section, and pairs of opposite sides are extended until they meet, the three intersection points will lie on a straight line, the "Pascal line" of that configuration.

Cyclic hexagon

[edit]The Lemoine hexagon is a cyclic hexagon (one inscribed in a circle) with vertices given by the six intersections of the edges of a triangle and the three lines that are parallel to the edges that pass through its symmedian point.

If the successive sides of a cyclic hexagon are a, b, c, d, e, f, then the three main diagonals intersect in a single point if and only if ace = bdf.[8]

If, for each side of a cyclic hexagon, the adjacent sides are extended to their intersection, forming a triangle exterior to the given side, then the segments connecting the circumcenters of opposite triangles are concurrent.[9]

If a hexagon has vertices on the circumcircle of an acute triangle at the six points (including three triangle vertices) where the extended altitudes of the triangle meet the circumcircle, then the area of the hexagon is twice the area of the triangle.[10]: p. 179

Hexagon tangential to a conic section

[edit]Let ABCDEF be a hexagon formed by six tangent lines of a conic section. Then Brianchon's theorem states that the three main diagonals AD, BE, and CF intersect at a single point.

In a hexagon that is tangential to a circle and that has consecutive sides a, b, c, d, e, and f,[11]

Equilateral triangles on the sides of an arbitrary hexagon

[edit]

If an equilateral triangle is constructed externally on each side of any hexagon, then the midpoints of the segments connecting the centroids of opposite triangles form another equilateral triangle.[12]: Thm. 1

Skew hexagon

[edit]

A skew hexagon is a skew polygon with six vertices and edges but not existing on the same plane. The interior of such a hexagon is not generally defined. A skew zig-zag hexagon has vertices alternating between two parallel planes.

A regular skew hexagon is vertex-transitive with equal edge lengths. In three dimensions it will be a zig-zag skew hexagon and can be seen in the vertices and side edges of a triangular antiprism with the same D3d, [2+,6] symmetry, order 12.

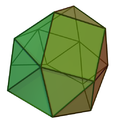

The cube and octahedron (same as triangular antiprism) have regular skew hexagons as petrie polygons.

Cube |

Octahedron |

Petrie polygons

[edit]The regular skew hexagon is the Petrie polygon for these higher dimensional regular, uniform and dual polyhedra and polytopes, shown in these skew orthogonal projections:

| 4D | 5D | |

|---|---|---|

3-3 duoprism |

3-3 duopyramid |

5-simplex |

Convex equilateral hexagon

[edit]A principal diagonal of a hexagon is a diagonal which divides the hexagon into quadrilaterals. In any convex equilateral hexagon (one with all sides equal) with common side a, there exists[13]: p.184, #286.3 a principal diagonal d1 such that

and a principal diagonal d2 such that

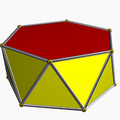

Polyhedra with hexagons

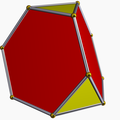

[edit]There is no Platonic solid made of only regular hexagons, because the hexagons tessellate, not allowing the result to "fold up". The Archimedean solids with some hexagonal faces are the truncated tetrahedron, truncated octahedron, truncated icosahedron (of soccer ball and fullerene fame), truncated cuboctahedron and the truncated icosidodecahedron. These hexagons can be considered truncated triangles, with Coxeter diagrams of the form ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() and

and ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

| Hexagons in Archimedean solids | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrahedral | Octahedral | Icosahedral | |||||||||

truncated tetrahedron |

truncated octahedron |

truncated cuboctahedron |

truncated icosahedron |

truncated icosidodecahedron | |||||||

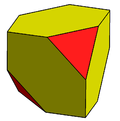

There are other symmetry polyhedra with stretched or flattened hexagons, like these Goldberg polyhedron G(2,0):

| Hexagons in Goldberg polyhedra | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrahedral | Octahedral | Icosahedral | |||||||||

Chamfered tetrahedron |

Chamfered cube |

Chamfered dodecahedron | |||||||||

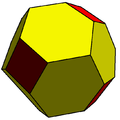

There are also 9 Johnson solids with regular hexagons:

| Prismoids with hexagons | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hexagonal prism |

Hexagonal antiprism |

Hexagonal pyramid | |||||||||

| Tilings with regular hexagons | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | 1-uniform | ||||||||||

| {6,3} |

r{6,3} |

rr{6,3} |

tr{6,3} | ||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||

| 2-uniform tilings | |||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||

Hexagon versus Sexagon

[edit]The debate over whether hexagons should be referred to as "sexagons" has its roots in the etymology of the term. The prefix "hex-" originates from the Greek word "hex," meaning six, while "sex-" comes from the Latin "sex," also signifying six. Some linguists and mathematicians argue that since many English mathematical terms derive from Latin, the use of "sexagon" would align with this tradition. Historical discussions date back to the 19th century, when mathematicians began to standardize terminology in geometry. However, the term "hexagon" has prevailed in common usage and academic literature, solidifying its place in mathematical terminology despite the historical argument for "sexagon." The consensus remains that "hexagon" is the appropriate term, reflecting its Greek origins and established usage in mathematics. (see Numeral_prefix#Occurrences).

Gallery of natural and artificial hexagons

[edit]-

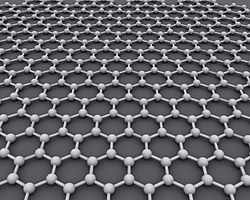

The ideal crystalline structure of graphene is a hexagonal grid.

-

Assembled E-ELT mirror segments

-

A beehive honeycomb

-

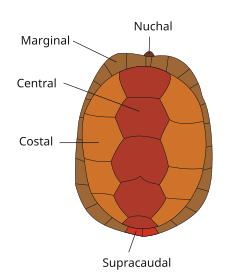

The scutes of a turtle's carapace

-

Saturn's hexagon, a hexagonal cloud pattern around the north pole of the planet

-

Micrograph of a snowflake

-

Benzene, the simplest aromatic compound with hexagonal shape.

-

Hexagonal order of bubbles in a foam.

-

Crystal structure of a molecular hexagon composed of hexagonal aromatic rings.

-

Naturally formed basalt columns from Giant's Causeway in Northern Ireland; large masses must cool slowly to form a polygonal fracture pattern

-

An aerial view of Fort Jefferson in Dry Tortugas National Park

-

The James Webb Space Telescope mirror is composed of 18 hexagonal segments.

-

In French, l'Hexagone refers to Metropolitan France for its vaguely hexagonal shape.

-

Hexagonal Hanksite crystal, one of many hexagonal crystal system minerals

-

Hexagonal barn

-

Władysław Gliński's hexagonal chess

-

Pavilion in the Taiwan Botanical Gardens

See also

[edit]- 24-cell: a four-dimensional figure which, like the hexagon, has orthoplex facets, is self-dual and tessellates Euclidean space

- Hexagonal crystal system

- Hexagonal number

- Hexagonal tiling: a regular tiling of hexagons in a plane

- Hexagram: six-sided star within a regular hexagon

- Unicursal hexagram: single path, six-sided star, within a hexagon

- Honeycomb theorem

- Havannah: abstract board game played on a six-sided hexagonal grid

- Central place theory

References

[edit]- ^ Cube picture

- ^ Wenninger, Magnus J. (1974), Polyhedron Models, Cambridge University Press, p. 9, ISBN 9780521098595, archived from the original on 2016-01-02, retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ^ a b Meskhishvili, Mamuka (2020). "Cyclic Averages of Regular Polygons and Platonic Solids". Communications in Mathematics and Applications. 11: 335–355. arXiv:2010.12340. doi:10.26713/cma.v11i3.1420 (inactive 12 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Johnston, Bernard L.; Richman, Fred (1997), Numbers and Symmetry: An Introduction to Algebra, CRC Press, p. 92, ISBN 978-0-8493-0301-2.

- ^ John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, (2008) The Symmetries of Things, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 20, Generalized Schaefli symbols, Types of symmetry of a polygon pp. 275–278)

- ^ Dunajski, Maciej (2022). Geometry: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-19-968368-0.

- ^ Coxeter, Mathematical recreations and Essays, Thirteenth edition, p.141

- ^ Cartensen, Jens, "About hexagons", Mathematical Spectrum 33(2) (2000–2001), 37–40.

- ^ Dergiades, Nikolaos (2014). "Dao's theorem on six circumcenters associated with a cyclic hexagon". Forum Geometricorum. 14: 243–246. Archived from the original on 2014-12-05. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ^ Johnson, Roger A., Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover Publications, 2007 (orig. 1960).

- ^ Gutierrez, Antonio, "Hexagon, Inscribed Circle, Tangent, Semiperimeter", [1] Archived 2012-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, Accessed 2012-04-17.

- ^ Dao Thanh Oai (2015). "Equilateral triangles and Kiepert perspectors in complex numbers". Forum Geometricorum. 15: 105–114. Archived from the original on 2015-07-05. Retrieved 2015-04-12.

- ^ Inequalities proposed in "Crux Mathematicorum", [2] Archived 2017-08-30 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

[edit]- Definition and properties of a hexagon with interactive animation and construction with compass and straightedge.

- An Introduction to Hexagonal Geometry on Hexnet a website devoted to hexagon mathematics.

- Hexagons are the Bestagons on YouTube – an animated internet video about hexagons by CGP Grey.

Hexagon

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Classification

A hexagon is a polygon consisting of six edges (sides) and six vertices, forming a closed plane figure.[6] Simple hexagons are non-self-intersecting, meaning their sides do not cross each other except at vertices, whereas complex hexagons are self-intersecting and may have overlapping edges.[7] Hexagons are classified based on their angles and side lengths. A convex hexagon has all interior angles less than 180 degrees, ensuring that the line segment between any two points inside the hexagon lies entirely within it; in contrast, a concave hexagon has at least one interior angle greater than 180 degrees, causing part of the polygon to "dent" inward.[7] Hexagons can also be equilateral, with all six sides of equal length, or equiangular, with all interior angles equal; a regular hexagon satisfies both conditions simultaneously, while irregular hexagons do not meet either criterion uniformly. For any simple hexagon, the sum of the interior angles is 720°, calculated as (6-2) × 180°.[6][8] The perimeter of a general hexagon is the sum of its six side lengths, , where denote the respective side lengths.[7] Its area can be determined by triangulating the hexagon from one vertex into four triangles—by drawing diagonals to the three non-adjacent vertices—and summing the areas of those triangles using standard triangle area formulas.[9] The term "hexagon" originates from the Greek words hex (six) and gonia (angle), referring to its six-angled structure, and was first employed in the context of Euclidean geometry.[10] The regular hexagon represents a special case in this classification, featuring equal sides and 120-degree interior angles.[6]Etymology and Terminology

The term "hexagon" derives from the Ancient Greek ἑξάγωνον (hexágōnon), a neuter form of ἑξάγωνος (hexágōnos), combining ἕξ (héz), meaning "six," with γωνία (gōnía), meaning "angle" or "corner," thus denoting a figure with six angles.[10][11] This etymology reflects the geometric emphasis on angles in Greek nomenclature for polygons. In contrast, the archaic English term "sexagon" stems from the Latin sex (meaning "six") combined with the Greek γωνία, creating a hybrid form that mixes Latin and Greek roots, which is generally avoided in classical scientific terminology for consistency.[12][13] The first systematic mathematical description of the hexagon as a plane figure appears in Euclid's Elements (c. 300 BCE), particularly in Book IV, Proposition 15, where Euclid details the construction of an equilateral and equiangular hexagon inscribed in a circle.[14] Over time, the term evolved in geometry texts, with "hexagon" becoming the standard in modern English usage by the 16th century, as seen in early translations and treatises adopting the Greek-derived form for clarity and tradition.[15] The preference for "hexagon" over "sexagon" in English arose from a desire to maintain uniformity with other polygon names like pentagon and heptagon, which use Greek prefixes, rendering "sexagon" obsolete and rarely used today.[12] There is no mathematical distinction between the two terms; both refer identically to a six-sided polygon.[16] In some languages, the word takes on unique cultural connotations; for instance, in French, "hexagone" commonly denotes metropolitan France itself, due to the country's approximate hexagonal outline on maps, a usage popularized in media and literature since the mid-20th century.[17]Regular Hexagon

Geometric Measurements

A regular hexagon, with side length denoted as , has a perimeter [18]. Each interior angle measures 120°, derived from the general formula for the interior angle of a regular -gon, , where [18]. The sum of the interior angles is [18]. The distance from the center to a vertex, known as the circumradius , equals the side length , so [18]. The apothem, or distance from the center to the midpoint of a side (also the inradius ), is [18]. These relations stem from the hexagon's decomposition into six equilateral triangles of side . The area of a regular hexagon can be calculated as , which is equivalent to six times the area of an equilateral triangle with side , or [18]. Alternatively, using the apothem and perimeter, [18]. Regular hexagons tessellate the Euclidean plane without gaps or overlaps, with three meeting at each vertex, achieving 100% coverage due to the 120° interior angle allowing precise adjacency[19].Construction and Symmetry

A regular hexagon can be constructed using a compass and straightedge by drawing a circle of arbitrary radius, which will serve as the circumcircle, and then setting the compass to this radius to mark off six equal arcs around the circumference starting from any point on the circle.[20] The intersection points of these arcs with the circle define the six vertices of the hexagon, which are then connected sequentially with the straightedge to form the polygon. This method exploits the property that the side length of a regular hexagon equals its circumradius, ensuring all sides and central angles are equal.[18] An alternative approach involves constructing two overlapping equilateral triangles to form a hexagram (Star of David), where the inner intersection region yields a regular hexagon, though the circle-division method remains the primary and most direct technique described in classical geometry.[21] The symmetry of a regular hexagon is governed by the dihedral group , which comprises 12 elements: six rotational symmetries by angles of and about its center, and six reflectional symmetries.[22] These reflections occur across six axes of symmetry passing through the center: three lines each joining a pair of opposite vertices, and three lines each joining the midpoints of a pair of opposite sides.[18]Centers and Points

In a regular hexagon with side length , the centroid, circumcenter, incenter, and orthocenter all coincide at a single geometric center due to the polygon's high degree of symmetry.[18] The centroid, defined as the intersection of the medians connecting opposite vertices, represents the balance point of the figure.[18] Similarly, the circumcenter is the center of the circumscribed circle passing through all vertices, while the incenter is the center of the inscribed circle tangent to all sides; both align precisely with the centroid.[18] The orthocenter, interpreted through the altitudes of the triangular sectors formed by the center and vertices, also converges at this point.[18] The distance from the center to any vertex, known as the circumradius , equals the side length .[18] Key points include the midpoints of the sides, which lie on the incircle and form a smaller regular hexagon when connected.[18] The intersection points of the diagonals are particularly significant: the three long diagonals, each connecting opposite vertices and measuring in length, intersect concurrently at the center.[18][23] These long diagonals divide the hexagon into six equilateral triangles, each with side length .[18] Shorter diagonals, connecting vertices separated by one intervening vertex and measuring , intersect at additional points away from the center but do not alter the central concurrence.[23] Due to the coincidence of all primary centers, the Euler line in a regular hexagon degenerates to a single point at the geometric center.[18] This alignment underscores the hexagon's uniformity. Additionally, specific points such as opposite vertices and side midpoints define a decomposition of the hexagon into a rectangle flanked by two equilateral triangles, facilitating geometric analysis.[24]Properties of Regular Hexagons

Dissections

A regular hexagon can be easily dissected into six congruent equilateral triangles by drawing lines from its center to each of the six vertices; each triangle has side length equal to that of the hexagon and shares the center as a vertex.[25] This basic dissection underscores the hexagon's geometric relationship to equilateral triangles and serves as a foundation for more complex cuttings.[26] More advanced dissections of a regular hexagon exploit its area equivalence to other polygons, as guaranteed by the Wallace–Bolyai–Gerwien theorem, which states that any two simple polygons of equal area can be dissected into each other using a finite number of polygonal pieces via straight cuts and rigid motions.[27] For instance, a regular hexagon can be dissected into a square of the same area using a minimum of 5 pieces, a solution first achieved by Paul-Jean Busschop in the 1870s.[28] Similarly, a regular hexagon can be dissected into an equilateral triangle of equal area in 5 pieces, as constructed by Harry Lindgren in 1961 using ruler-and-compass methods.[29] Although the Wallace–Bolyai–Gerwien theorem extends to irregular hexagons, enabling their dissection into other polygons of equal area, examples and minimal-piece solutions predominantly emphasize the regular hexagon owing to its high symmetry, which facilitates elegant and minimal cuttings.[27]Tessellations and Tilings

Regular hexagons tessellate the Euclidean plane in a regular pattern known as the hexagonal tiling, where exactly three hexagons meet at each vertex. This configuration arises because each internal angle measures 120 degrees, and three such angles sum to 360 degrees, allowing the polygons to fit precisely without gaps or overlaps and covering the entire plane.[30] The tiling is denoted by the Schläfli symbol {6,3}, signifying six edges per face and three faces meeting at each vertex, and is commonly referred to as the honeycomb tiling due to its resemblance to beehive structures.[31] The hexagonal tiling is the dual of the regular triangular tiling {3,6}, in which the vertices of the hexagonal tiling correspond to the centers of the triangles, and vice versa, creating a complementary arrangement of the plane.[32] This dual relationship highlights the symmetry between the two regular tessellations. The structure is prevalent in natural and material sciences, notably forming the basis of crystal lattices such as that in graphene, where carbon atoms arrange in a honeycomb pattern of interconnected hexagons, enabling unique electronic properties.[33] In hyperbolic geometry, regular hexagonal tilings extend beyond the Euclidean case, with more than three hexagons meeting at each vertex to accommodate the negative curvature, resulting in infinitely many such tilings; for instance, the order-4 hexagonal tiling {6,4} has four hexagons per vertex.[34] On the sphere, pure regular hexagonal tilings are not possible due to positive curvature, but finite configurations approximating hexagonal arrangements appear in polyhedra like the truncated icosahedron, an Archimedean solid with 20 regular hexagonal faces alongside 12 pentagonal faces to close the surface.[35] Beyond pure hexagonal tessellations, regular hexagons combine with other regular polygons in the 11 Archimedean tilings of the plane, which are vertex-transitive and use two or more polygon types. Representative examples include the trihexagonal tiling (vertex figure 3.6.3.6), alternating equilateral triangles and hexagons around each vertex, and the snub hexagonal tiling (3.3.3.3.6), a chiral pattern of four triangles and one hexagon per vertex that fills the plane with rotational symmetry.[36]Generalizations and Variants

Inscribed and Tangential Hexagons

An inscribed hexagon is a six-sided polygon whose vertices all lie on a conic section, such as an ellipse, parabola, or hyperbola. A fundamental property of such hexagons is given by Pascal's theorem, which states that if a hexagon is inscribed in a conic, the intersections of the three pairs of its opposite sides lie on a straight line.[37] This theorem holds for any conic and applies to both convex and non-convex hexagons, provided the sides can be extended appropriately. When the conic is a circle, the hexagon is cyclic, meaning it can be circumscribed by a circle passing through all vertices. For cyclic hexagons, additional relations among side lengths and diagonals emerge as generalizations of Ptolemy's theorem for quadrilaterals. Fuhrmann's theorem provides one such relation: in a convex cyclic hexagon with opposite sides , , and corresponding diagonals connecting alternate vertices, the equality holds.[38] If the cyclic hexagon is also equilateral—all sides equal—it reduces to a regular hexagon. A tangential hexagon, in contrast, has all its sides tangent to a conic section. The dual of Pascal's theorem, Brianchon's theorem, asserts that for a hexagon tangential to a conic, the three diagonals joining opposite vertices are concurrent at a single point.[39] For such a hexagon to exist around a given conic (particularly a circle as the incircle), the necessary and sufficient condition is that the sums of the lengths of every other side are equal: if the sides are in sequence, then .[40] This generalizes Pitot's theorem from quadrilaterals and ensures the tangency points divide the perimeter appropriately. When the conic is an ellipse, inscribed hexagons can be irregular, with vertices distributed unevenly along the curve. The configuration that maximizes the area of an inscribed hexagon in an ellipse is the affine transformation of a regular hexagon inscribed in a unit circle, preserving the maximum-area property under affine mappings.[41] This "regular-like" hexagon achieves an area scaled by the ellipse's semi-axes, emphasizing the role of symmetry in optimization despite the ellipse's eccentricity.Skew and Equilateral Hexagons

A skew hexagon is a non-planar polygon consisting of six vertices and edges that do not all lie in the same plane, forming a closed chain in three-dimensional space.[42] Unlike planar hexagons, its vertices typically alternate above and below a reference plane, creating a zig-zag or helical path.[42] These structures appear in uniform polyhedra, where they serve as non-planar faces or skeletal elements, maintaining regularity in edge lengths and angles despite their three-dimensional embedding.[43] Petrie polygons provide a key example of skew hexagons, defined as closed paths on a polyhedron where consecutive edges do not belong to the same face, resulting in a skew traversal of the structure.[44] In the regular octahedron, a triangular antiprism, the Petrie polygons are equilateral skew hexagons that wind around the figure, connecting vertices in a non-planar circuit and highlighting the polyhedron's symmetry.[44] Similarly, the regular dodecahedron features skew hexagons as Petrie paths, which can be oriented parallel to the faces of its dual icosahedron and contribute to compounds like triangular antiprisms.[44] In antiprisms, such skew hexagons often manifest as zig-zag chains formed by the lateral edges, linking the two parallel bases in a twisted configuration.[45] Convex equilateral hexagons are planar polygons with all six sides of equal length but varying interior angles, distinguishing them from regular hexagons where both sides and angles are uniform.[46] These hexagons lack a circumcircle in general, as their vertices do not lie on a common circle unless the angles are all 120 degrees, making them regular.[46] They can be arranged into zig-zag chains, where alternating orientations allow for flexible tiling patterns or structural formations without requiring equal angles.[46] For non-convex variants, the area can be computed using vector cross products to account for the irregular projections, providing a method to quantify enclosed space despite indentations.Self-Crossing and Related Polygons

Self-crossing hexagons are non-simple polygons whose edges intersect, creating star-like or compound forms rather than convex or concave boundaries. A canonical example is the regular star hexagon with Schläfli symbol {6/2}, commonly known as the hexagram or Star of David, which manifests as a geometric compound of two equilateral triangles interlocked at their vertices. This configuration arises because 6 and 2 share a common factor, reducing {6/2} to a degenerate star polygon equivalent to two instances of the triangle {3}. The density of {6/2}, defined as the number of times the polygon's boundary winds around its center, is 2, reflecting the overlapping structure.[47] Unlike simple polygons, self-crossing hexagons require specialized methods for area computation due to their intersecting regions. The shoelace formula, when applied to such figures, yields a signed area that accounts for winding numbers: the total is the sum of each enclosed region's area multiplied by the winding number of the boundary relative to a point inside that region. For the {6/2} hexagram, the central hexagonal region has a winding number of 2, while the six surrounding triangular points each have a winding number of 1, allowing precise delineation of the figure's effective coverage.[48] A notable variant is the unicursal hexagram, a self-intersecting hexagon drawable in one continuous line without retracing or lifting the pen, unlike the standard {6/2} compound which demands separate strokes for each triangle. This form, discovered in the 19th century, features six points but lacks full regularity, as some edges differ in length from others, resulting in a non-equilateral structure.[21] In tiling contexts, self-crossing hexagons remain uncommon, particularly in Euclidean plane coverings, but they emerge in compound forms that extend traditional tessellations and in non-Euclidean or aperiodic arrangements. For instance, star hexagons like {6/2} can integrate into compounds for hyperbolic tilings, where higher densities allow more complex intersections. They also relate to hexiamonds—figures and tilings built from six equilateral triangles forming hexagonal outlines—though hexiamonds themselves are typically non-crossing.[47]Applications and Structures

Natural and Artificial Hexagons

Hexagonal patterns appear frequently in natural formations due to their structural efficiency in packing and symmetry. In beehives, honeycombs consist of hexagonal cells that optimize space and material use, with each cell featuring interior angles of 120 degrees to facilitate stable tessellation and minimize wax consumption.[49] This configuration allows bees to construct cylindrical cells that deform into hexagons as wax cools and surface tension balances, providing mechanical strength.[50] Snowflakes exhibit six-fold hexagonal symmetry arising from the molecular structure of water ice, where hydrogen bonds form a hexagonal lattice that dictates crystal growth patterns under varying temperature and humidity conditions.[51] As water vapor deposits onto the crystal, this lattice leads to symmetrical branching into hexagonal plates or prisms.[52] Similarly, basalt columns, such as those at the Giant's Causeway in Northern Ireland, form through the cooling and contraction of molten lava, resulting in polygonal fractures predominantly hexagonal in cross-section due to tensile stress relief in the contracting material.[53] These columns, numbering over 40,000, emerged from volcanic activity about 60 million years ago.[54] In biological systems, hexagonal arrangements enhance packing density and functionality. The compound eyes of insects, such as those in Drosophila, feature a quasi-crystalline array of hexagonal facets called ommatidia, which maximize light capture and resolution through precise cell recruitment and spacing during development.[55] This hexagonal patterning ensures uniform coverage of the visual field with minimal gaps. Viral capsids, like that of adenovirus, incorporate hexagonal symmetry in their icosahedral structure, with 240 hexon trimers forming the primary shell to enclose the genome efficiently.[56] The capsid's pseudo-T=25 organization relies on these hexons for stability, with each facet comprising a network of triangularly arranged hexons.[57] Artificial designs leverage hexagonal lattices for efficiency and performance. In semiconductors, materials like graphene and gallium nitride (GaN) utilize hexagonal lattices to enable high electron mobility and epitaxial growth; for instance, graphene's honeycomb structure serves as a template for GaN layers, matching lattice symmetry to reduce defects in optoelectronic devices.[58] Architecturally, hexagonal forms inspire structures like the Interlace in Singapore, where 31 six-story blocks are stacked in hexagonal clusters to optimize ventilation, green space, and urban density.[59] Hexagonal tiling proves efficient in two-dimensional foams, minimizing perimeter for a given area according to the honeycomb theorem, as explored in the Lord Kelvin problem, though three-dimensional solutions like the Weaire-Phelan structure surpass Kelvin's tetrakaidecahedron.[60] In the 2020s, hexagonal arrays in metamaterials have advanced photonics, enabling flat lenses and absorbers; for example, dielectric metasurfaces with hexagonal meta-atoms achieve angle-insensitive resonances for compact imaging systems.[61] These applications exploit the arrays' ability to manipulate light propagation with subwavelength precision.[62]Polyhedra and Higher-Dimensional Figures

Regular hexagons serve as faces in several Archimedean solids, which are uniform polyhedra composed of regular polygons meeting in the same configuration at each vertex. The truncated tetrahedron features four regular hexagonal faces alongside four equilateral triangular faces.[63] Similarly, the truncated octahedron includes eight regular hexagonal faces and six square faces, while the truncated cuboctahedron (also known as the great rhombicuboctahedron) has eight regular hexagonal faces, twelve square faces, and six octagonal faces.[64] These structures exemplify how hexagonal faces integrate with other regular polygons to form convex, vertex-transitive polyhedra. A prominent example is the truncated icosahedron, an Archimedean solid with twenty regular hexagonal faces and twelve pentagonal faces, which defines the geometry of a traditional soccer ball.[35] This polyhedron also models the molecular structure of buckminsterfullerene (C60), a fullerene discovered in 1985, where sixty carbon atoms form a cage of fused pentagons and hexagons resembling a truncated icosahedron.[65] Among the 75 non-prismatic uniform polyhedra, hexagonal faces appear in at least four such Archimedean examples, highlighting their role in symmetric three-dimensional constructions. Additionally, Petrie polygons—skew paths tracing edges where consecutive sides lie on distinct faces—manifest as skew hexagons in polyhedra like the cube and octahedron.[66] Hexagons extend to prismatic polyhedra and space-filling structures, such as the hexagonal prism, a uniform polyhedron with two parallel hexagonal bases and six rectangular lateral faces.[67] In three dimensions, the hexagonal prismatic honeycomb tessellates Euclidean space with hexagonal prisms meeting six at each vertex, forming a uniform honeycomb.[68] Higher-dimensional analogs include prismatic uniform 4-polytopes, where products of hexagonal tilings with intervals or other polytopes incorporate hexagonal elements as cells or facets. These constructions generalize hexagonal symmetry to four dimensions, as seen in families of uniform polychora derived from prismatic symmetries. In applications, regular hexagons underpin crystal structures like the hexagonal close-packed (hcp) lattice, where atoms arrange in alternating ABAB layers of close-packed hexagonal planes, achieving a packing efficiency of 74%.[69] This structure occurs in metals such as magnesium, zinc, and cobalt, providing stability through dense, symmetric atomic coordination.[70]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/hexagon

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/sexagon

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}A&={\frac {3{\sqrt {3}}}{2}}R^{2}=3Rr=2{\sqrt {3}}r^{2}\\[3pt]&={\frac {3{\sqrt {3}}}{8}}D^{2}={\frac {3}{4}}Dd={\frac {\sqrt {3}}{2}}d^{2}\\[3pt]&\approx 2.598R^{2}\approx 3.464r^{2}\\&\approx 0.6495D^{2}\approx 0.866d^{2}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/67e6b4ae01ba9dc79d7c7dd7fa50b2613799966c)