Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Penrose tiling

View on Wikipedia

A Penrose tiling is an example of an aperiodic tiling. Here, a tiling is a covering of the plane by non-overlapping polygons or other shapes, and a tiling is aperiodic if it does not contain arbitrarily large periodic regions or patches. However, despite their lack of translational symmetry, Penrose tilings may have both reflection symmetry and fivefold rotational symmetry. Penrose tilings are named after mathematician and physicist Roger Penrose, who investigated them in the 1970s.

There are several variants of Penrose tilings with different tile shapes. The original form of Penrose tiling used tiles of four different shapes, but this was later reduced to only two shapes: either two different rhombi, or two different quadrilaterals called kites and darts. The Penrose tilings are obtained by constraining the ways in which these shapes are allowed to fit together in a way that avoids periodic tiling. This may be done in several different ways, including matching rules, substitution tiling or finite subdivision rules, cut and project schemes, and coverings. Even constrained in this manner, each variation yields infinitely many different Penrose tilings.

Penrose tilings are self-similar: they may be converted to equivalent Penrose tilings with different sizes of tiles, using processes called inflation and deflation. The pattern represented by every finite patch of tiles in a Penrose tiling occurs infinitely many times throughout the tiling. They are quasicrystals: implemented as a physical structure a Penrose tiling will produce diffraction patterns with Bragg peaks and five-fold symmetry, revealing the repeated patterns and fixed orientations of its tiles.[1] The study of these tilings has been important in the understanding of physical materials that also form quasicrystals.[2] Penrose tilings have also been applied in architecture and decoration, as in the floor tiling shown.

The 2011 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for "The Discovery of Quasicrystals." Penrose tiling was mentioned for having "'helped pave the way for the understanding of the discovery of quasicrystals.'"[3][4]

Background and history

[edit]Periodic and aperiodic tilings

[edit]

Covering a flat surface ("the plane") with some pattern of geometric shapes ("tiles"), with no overlaps or gaps, is called a tiling. The most familiar tilings, such as covering a floor with squares meeting edge-to-edge, are examples of periodic tilings. If a square tiling is shifted by the width of a tile, parallel to the sides of the tile, the result is the same pattern of tiles as before the shift. A shift (formally, a translation) that preserves the tiling in this way is called a period of the tiling. A tiling is called periodic when it has periods that shift the tiling in two different directions.[5]

The tiles in the square tiling have only one shape, and it is common for other tilings to have only a finite number of shapes. These shapes are called prototiles, and a set of prototiles is said to admit a tiling or tile the plane if there is a tiling of the plane using only these shapes. That is, each tile in the tiling must be congruent to one of these prototiles.[6]

A tiling that has no periods is non-periodic. A set of prototiles is said to be aperiodic if all of its tilings are non-periodic, and in this case its tilings are also called aperiodic tilings.[7] Penrose tilings are among the simplest known examples of aperiodic tilings of the plane by finite sets of prototiles.[5]

Earliest aperiodic tilings

[edit]

The subject of aperiodic tilings received new interest in the 1960s when logician Hao Wang noted connections between decision problems and tilings.[9] In particular, he introduced tilings by square plates with colored edges, now known as Wang dominoes or tiles, and posed the "Domino Problem": to determine whether a given set of Wang dominoes could tile the plane with matching colors on adjacent domino edges. He observed that if this problem were undecidable, then there would have to exist an aperiodic set of Wang dominoes. At the time, this seemed implausible, so Wang conjectured no such set could exist.

Wang's student Robert Berger proved that the Domino Problem was undecidable (so Wang's conjecture was incorrect) in his 1964 thesis,[10] and obtained an aperiodic set of 20,426 Wang dominoes.[11] He also described a reduction to 104 such prototiles; the latter did not appear in his published monograph,[12] but in 1968, Donald Knuth detailed a modification of Berger's set requiring only 92 dominoes.[13]

The color matching required in a tiling by Wang dominoes can easily be achieved by modifying the edges of the tiles like jigsaw puzzle pieces so that they can fit together only as prescribed by the edge colorings.[14] Raphael Robinson, in a 1971 paper[15] which simplified Berger's techniques and undecidability proof, used this technique to obtain an aperiodic set of just six prototiles.[16]

Development of the Penrose tilings

[edit]

The first Penrose tiling (tiling P1 below) is an aperiodic set of six prototiles, introduced by Roger Penrose in a 1974 paper,[18] based on pentagons rather than squares. Any attempt to tile the plane with regular pentagons necessarily leaves gaps, but Johannes Kepler showed, in his 1619 work Harmonices Mundi, that these gaps can be filled using pentagrams (star polygons), decagons and related shapes.[19] Kepler extended this tiling by five polygons and found no periodic patterns, and already conjectured that every extension would introduce a new feature[20] hence creating an aperiodic tiling. Traces of these ideas can also be found in the work of Albrecht Dürer.[21] Acknowledging inspiration from Kepler, Penrose found matching rules for these shapes, obtaining an aperiodic set. These matching rules can be imposed by decorations of the edges, as with the Wang tiles. Penrose's tiling can be viewed as a completion of Kepler's finite Aa pattern.[22]

Penrose subsequently reduced the number of prototiles to two, discovering the kite and dart tiling (tiling P2 below) and the rhombus tiling (tiling P3 below).[23] The rhombus tiling was independently discovered by Robert Ammann in 1976.[24] Penrose and John H. Conway investigated the properties of Penrose tilings, and discovered that a substitution property explained their hierarchical nature; their findings were publicized by Martin Gardner in his January 1977 "Mathematical Games" column in Scientific American.[25]

In 1981, N. G. de Bruijn provided two different methods to construct Penrose tilings. De Bruijn's "multigrid method" obtains the Penrose tilings as the dual graphs of arrangements of five families of parallel lines. In his "cut and project method", Penrose tilings are obtained as two-dimensional projections from a five-dimensional cubic structure. In these approaches, the Penrose tiling is viewed as a set of points, its vertices, while the tiles are geometrical shapes obtained by connecting vertices with edges.[26] A 1990 construction by Baake, Kramer, Schlottmann, and Zeidler derived the Penrose tiling and the related Tübingen triangle tiling in a similar manner from the four-dimensional 5-cell honeycomb.[27]

Penrose tilings

[edit]

The three types of Penrose tiling, P1–P3, are described individually below.[28] They have many common features: in each case, the tiles are constructed from shapes related to the pentagon (and hence to the golden ratio), but the basic tile shapes need to be supplemented by matching rules in order to tile aperiodically. These rules may be described using labeled vertices or edges, or patterns on the tile faces; alternatively, the edge profile can be modified (e.g. by indentations and protrusions) to obtain an aperiodic set of prototiles.[11][29]

Original pentagonal Penrose tiling (P1)

[edit]Penrose's first tiling uses pentagons and three other shapes: a five-pointed "star" (a pentagram), a "boat" (also known as a "justice cap",[30] roughly 3/5 of a star) and a "diamond" (a thin rhombus).[31] To ensure that all tilings are non-periodic, there are matching rules that specify how tiles may meet each other, and there are three different types of matching rule for the pentagonal tiles. Treating these three types as different prototiles gives a set of six prototiles overall. It is common to indicate the three different types of pentagonal tiles using three different colors, as in the figure above right.[32]

Kite and dart tiling (P2)

[edit]

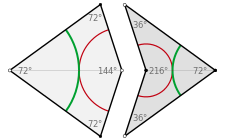

Penrose's second tiling uses quadrilaterals called the "kite" and "dart", which may be combined to make a rhombus. However, the matching rules prohibit such a combination.[33] Both the kite and dart are composed of two triangles, called Robinson triangles, after 1975 notes by Robinson.[34]

- The kite is a quadrilateral whose four interior angles are 72, 72, 72, and 144 degrees. The kite may be bisected along its axis of symmetry to form a pair of acute Robinson triangles (with angles of 36, 72 and 72 degrees).

- The dart is a non-convex quadrilateral whose four interior angles are 36, 72, 36, and 216 degrees. The dart may be bisected along its axis of symmetry to form a pair of obtuse Robinson triangles (with angles of 36, 36 and 108 degrees), which are smaller than the acute triangles.

The matching rules can be described in several ways. One approach is to color the vertices (with two colors, e.g., black and white) and require that adjacent tiles have matching vertices.[35] Another is to use a pattern of circular arcs (as shown above left in green and red) to constrain the placement of tiles: when two tiles share an edge in a tiling, the patterns must match at these edges.[23]

These rules often force the placement of certain tiles: for example, the concave vertex of any dart is necessarily filled by two kites. The corresponding figure (center of the top row in the lower image on the left) is called an "ace" by Conway; although it looks like an enlarged kite, it does not tile in the same way.[36] Similarly the concave vertex formed when two kites meet along a short edge is necessarily filled by two darts (bottom right). In fact, there are only seven possible ways for the tiles to meet at a vertex; two of these figures – namely, the "star" (top left) and the "sun" (top right) – have 5-fold dihedral symmetry (by rotations and reflections), while the remainder have a single axis of reflection (vertical in the image).[37] Apart from the ace (top middle) and the sun, all of these vertex figures force the placement of additional tiles.[38]

Rhombus tiling (P3)

[edit]

The third tiling uses a pair of rhombuses (often referred to as "rhombs" in this context) with equal sides but different angles.[11] Ordinary rhombus-shaped tiles can be used to tile the plane periodically, so restrictions must be made on how tiles can be assembled: no two tiles may form a parallelogram, as this would allow a periodic tiling, but this constraint is not sufficient to force aperiodicity, as figure 1 above shows.

There are two kinds of tile, both of which can be decomposed into Robinson triangles.[34]

- The thin rhomb t has four corners with angles of 36, 144, 36, and 144 degrees. The t rhomb may be bisected along its short diagonal to form a pair of acute Robinson triangles.

- The thick rhomb T has angles of 72, 108, 72, and 108 degrees. The T rhomb may be bisected along its long diagonal to form a pair of obtuse Robinson triangles; in contrast to the P2 tiling, these are larger than the acute triangles.

The matching rules distinguish sides of the tiles, and entail that tiles may be juxtaposed in certain particular ways but not in others. Two ways to describe these matching rules are shown in the image on the right. In one form, tiles must be assembled such that the curves on the faces match in color and position across an edge. In the other, tiles must be assembled such that the bumps on their edges fit together.[11]

There are 54 cyclically ordered combinations of such angles that add up to 360 degrees at a vertex, but the rules of the tiling allow only seven of these combinations to appear (although one of these arises in two ways).[39]

The various combinations of angles and facial curvature allow construction of arbitrarily complex tiles, such as the Penrose chickens.[40]

Features and constructions

[edit]Golden ratio and local pentagonal symmetry

[edit]Several properties and common features of the Penrose tilings involve the golden ratio (approximately 1.618).[34][35] This is the ratio of chord lengths to side lengths in a regular pentagon, and satisfies φ = 1 + 1/φ.

Consequently, the ratio of the lengths of long sides to short sides in the (isosceles) Robinson triangles is φ:1. It follows that the ratio of long side lengths to short in both kite and dart tiles is also φ:1, as are the length ratios of sides to the short diagonal in the thin rhomb t, and of long diagonal to sides in the thick rhomb T. In both the P2 and P3 tilings, the ratio of the area of the larger Robinson triangle to the smaller one is φ:1, hence so are the ratios of the areas of the kite to the dart, and of the thick rhomb to the thin rhomb. (Both larger and smaller obtuse Robinson triangles can be found in the pentagon on the left: the larger triangles at the top – the halves of the thick rhomb – have linear dimensions scaled up by φ compared to the small shaded triangle at the base, and so the ratio of areas is φ2:1.)

Any Penrose tiling has local pentagonal symmetry, in the sense that there are points in the tiling surrounded by a symmetric configuration of tiles: such configurations have fivefold rotational symmetry about the center point, as well as five mirror lines of reflection symmetry passing through the point, a dihedral symmetry group.[11] This symmetry will generally preserve only a patch of tiles around the center point, but the patch can be very large: Conway and Penrose proved that whenever the colored curves on the P2 or P3 tilings close in a loop, the region within the loop has pentagonal symmetry, and furthermore, in any tiling, there are at most two such curves of each color that do not close up.[41]

There can be at most one center point of global fivefold symmetry: if there were more than one, then rotating each about the other would yield two closer centers of fivefold symmetry, which leads to a mathematical contradiction.[42] There are only two Penrose tilings (of each type) with global pentagonal symmetry: for the P2 tiling by kites and darts, the center point is either a "sun" or "star" vertex.[43]

Inflation and deflation

[edit]

Many of the common features of Penrose tilings follow from a hierarchical pentagonal structure given by substitution rules: this is often referred to as inflation and deflation, or composition and decomposition, of tilings or (collections of) tiles.[11][25][44] The substitution rules decompose each tile into smaller tiles of the same shape as those used in the tiling (and thus allow larger tiles to be "composed" from smaller ones). This shows that the Penrose tiling has a scaling self-similarity, and so can be thought of as a fractal, using the same process as the pentaflake.[45]

Penrose originally discovered the P1 tiling in this way, by decomposing a pentagon into six smaller pentagons (one half of a net of a dodecahedron) and five half-diamonds; he then observed that when he repeated this process the gaps between pentagons could all be filled by stars, diamonds, boats (or "justice caps"[30], as he puts it) and other pentagons.[31] By iterating this process indefinitely he obtained one of the two P1 tilings with pentagonal symmetry.[11][22]

Robinson triangle decompositions

[edit]

The substitution method for both P2 and P3 tilings can be described using Robinson triangles of different sizes. The Robinson triangles arising in P2 tilings (by bisecting kites and darts) are called A-tiles, while those arising in the P3 tilings (by bisecting rhombs) are called B-tiles.[34] The smaller A-tile, denoted AS, is an obtuse Robinson triangle, while the larger A-tile, AL, is acute; in contrast, a smaller B-tile, denoted BS, is an acute Robinson triangle, while the larger B-tile, BL, is obtuse.

Concretely, if AS has side lengths (1, 1, φ), then AL has side lengths (φ, φ, 1). B-tiles can be related to such A-tiles in two ways:

- If BS has the same size as AL then BL is an enlarged version φAS of AS, with side lengths (φ, φ, φ2 = 1 + φ) – this decomposes into an AL tile and AS tile joined along a common side of length 1.

- If instead BL is identified with AS, then BS is a reduced version (1/φ)AL of AL with side lengths (1/φ,1/φ,1) – joining a BS tile and a BL tile along a common side of length 1 then yields (a decomposition of) an AL tile.

In these decompositions, there appears to be an ambiguity: Robinson triangles may be decomposed in two ways, which are mirror images of each other in the (isosceles) axis of symmetry of the triangle. In a Penrose tiling, this choice is fixed by the matching rules. Furthermore, the matching rules also determine how the smaller triangles in the tiling compose to give larger ones.[34]

It follows that the P2 and P3 tilings are mutually locally derivable: a tiling by one set of tiles can be used to generate a tiling by another. For example, a tiling by kites and darts may be subdivided into A-tiles, and these can be composed in a canonical way to form B-tiles and hence rhombs.[17] The P2 and P3 tilings are also both mutually locally derivable with the P1 tiling (see figure 2 above).[46]

The decomposition of B-tiles into A-tiles may be written

- BS = AL, BL = AL + AS

(assuming the larger size convention for the B-tiles), which can be summarized in a substitution matrix equation:[47]

Combining this with the decomposition of enlarged φA-tiles into B-tiles yields the substitution

so that the enlarged tile φAL decomposes into two AL tiles and one AS tiles. The matching rules force a particular substitution: the two AL tiles in a φAL tile must form a kite, and thus a kite decomposes into two kites and a two half-darts, and a dart decomposes into a kite and two half-darts.[48][49] Enlarged φB-tiles decompose into B-tiles in a similar way (via φA-tiles).

Composition and decomposition can be iterated, so that, for example

The number of kites and darts in the nth iteration of the construction is determined by the nth power of the substitution matrix:

where Fn is the nth Fibonacci number. The ratio of numbers of kites to darts in any sufficiently large P2 Penrose tiling pattern therefore approximates to the golden ratio φ.[50] A similar result holds for the ratio of the number of thick rhombs to thin rhombs in the P3 Penrose tiling.[48]

Deflation for P2 and P3 tilings

[edit]Starting with a collection of tiles from a given tiling (which might be a single tile, a tiling of the plane, or any other collection), deflation proceeds with a sequence of steps called generations. In one generation of deflation, each tile is replaced with two or more new tiles that are scaled-down versions of tiles used in the original tiling. The substitution rules guarantee that the new tiles will be arranged in accordance with the matching rules.[48] Repeated generations of deflation produce a tiling of the original axiom shape with smaller and smaller tiles.

This rule for dividing the tiles is a subdivision rule.

| Name | Initial tiles | Generation 1 | Generation 2 | Generation 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Half-kite |

|

|

|

|

| Half-dart |

|

|

|

|

| Sun |

|

|

|

|

| Star |

|

|

|

|

The above table should be used with caution. The half kite and half dart deflation are useful only in the context of deflating a larger pattern as shown in the sun and star deflations. They give incorrect results if applied to single kites and darts.

In addition, the simple subdivision rule generates holes near the edges of the tiling which are just visible in the top and bottom illustrations on the right. Additional forcing rules are useful.

Consequences and applications

[edit]Inflation and deflation yield a method for constructing kite and dart (P2) tilings, or rhombus (P3) tilings, known as up-down generation.[36][48][49]

The Penrose tilings, being non-periodic, have no translational symmetry – the pattern cannot be shifted to match itself over the entire plane. However, any bounded region, no matter how large, will be repeated an infinite number of times within the tiling. Therefore, no finite patch can uniquely determine a full Penrose tiling, nor even determine which position within the tiling is being shown.[51]

This shows in particular that the number of distinct Penrose tilings (of any type) is uncountably infinite. Up-down generation yields one method to parameterize the tilings, but other methods use Ammann bars, pentagrids, or cut and project schemes.[48]

Related tilings and topics

[edit]Decagonal coverings and quasicrystals

[edit]

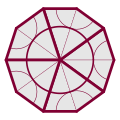

In 1996, German mathematician Petra Gummelt demonstrated that a covering (so called to distinguish it from a non-overlapping tiling) equivalent to the Penrose tiling can be constructed using a single decagonal tile if two kinds of overlapping regions are allowed.[53] The decagonal tile is decorated with colored patches, and the covering rule allows only those overlaps compatible with the coloring. A suitable decomposition of the decagonal tile into kites and darts transforms such a covering into a Penrose (P2) tiling. Similarly, a P3 tiling can be obtained by inscribing a thick rhomb into each decagon; the remaining space is filled by thin rhombs.

These coverings have been considered as a realistic model for the growth of quasicrystals: the overlapping decagons are 'quasi-unit cells' analogous to the unit cells from which crystals are constructed, and the matching rules maximize the density of certain atomic clusters.[52][54] The aperiodic nature of the coverings can make theoretical studies of physical properties, such as electronic structure, difficult due to the absence of Bloch's theorem. However, spectra of quasicrystals can still be computed with error control.[55]

Related tilings

[edit]

The three variants of the Penrose tiling are mutually locally derivable. Selecting some subsets from the vertices of a P1 tiling allows to produce other non-periodic tilings. If the corners of one pentagon in P1 are labeled in succession by 1,3,5,2,4 an unambiguous tagging in all the pentagons is established, the order being either clockwise or counterclockwise. Points with the same label define a tiling by Robinson triangles while points with the numbers 3 and 4 on them define the vertices of a Tie-and-Navette tiling.[56]

There are also other related unequivalent tilings, such as the hexagon-boat-star and Mikulla–Roth tilings. For instance, if the matching rules for the rhombus tiling are reduced to a specific restriction on the angles permitted at each vertex, a binary tiling is obtained.[57] Its underlying symmetry is also fivefold but it is not a quasicrystal. It can be obtained either by decorating the rhombs of the original tiling with smaller ones, or by applying substitution rules, but not by de Bruijn's cut-and-project method.[58]

Art and architecture

[edit]-

Pentagonal and decagonal Girih-tile pattern on a spandrel from the Darb-i Imam shrine, Isfahan, Iran (1453 C.E.)

-

Salesforce Transit Center in San Francisco. The outer "skin", made of white aluminum, is perforated in the pattern of a Penrose tiling.

-

Penrose tiling on the floor in Computer Center 3 (CC-3), IIIT Allahabad

The aesthetic value of tilings has long been appreciated, and remains a source of interest in them; hence the visual appearance (rather than the formal defining properties) of Penrose tilings has attracted attention. The similarity with certain decorative patterns used in North Africa and the Middle East has been noted;[59][60] the physicists Peter J. Lu and Paul Steinhardt have presented evidence that a Penrose tiling underlies examples of medieval Islamic geometric patterns, such as the girih (strapwork) tilings at the Darb-e Imam shrine in Isfahan.[61]

Artist Clark Richert used the same rhombs in artwork he was developing at Drop City in 1970 which he derived by projecting the rhombic triacontahedron shadow onto a plane and observing the embedded "fat" rhombi and "skinny" rhombi which tile together to produce the non-periodic tessellation, predating Penrose's discovery.[62] These geometric explorations led to the development of Steve Baer's Zome Architecture. Art historian Martin Kemp has observed that Albrecht Dürer sketched similar motifs of a rhombus tiling.[63]

In 1979, Miami University used a Penrose tiling executed in terrazzo to decorate the Bachelor Hall courtyard in their Department of Mathematics and Statistics.[64]

In Indian Institute of Information Technology, Allahabad, since the first phase of construction in 2001, academic buildings were designed on the basis of "Penrose Geometry", styled on tessellations developed by Roger Penrose. In many places in those buildings, the floor has geometric patterns composed of Penrose tiling.[65]

The floor of the atrium of the Bayliss Building at The University of Western Australia is tiled with Penrose tiles.[66]

The Andrew Wiles Building, the location of the Mathematics Department at the University of Oxford as of October 2013,[67] includes a section of Penrose tiling as the paving of its entrance.[68]

The pedestrian part of the street Keskuskatu in central Helsinki is paved using a form of Penrose tiling. The work was finished in 2014.[69]

San Francisco's 2018 Salesforce Transit Center features perforations in its exterior's undulating white metal skin in the Penrose pattern.[70]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Senechal 1996, pp. 241–244.

- ^ Radin 1996.

- ^ The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences (5 October 2011). "The Discovery of Quasicrystals" (PDF). www.nobelprize.org.

- ^ "Quasicrystals – Nobel Prize 2011 – Chemical Crystallography". www.xtl.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ a b General references for this article include Gardner 1997, pp. 1–30, Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, pp. 520–548 &, 558–579, and Senechal 1996, pp. 170–206.

- ^ Gardner 1997, pp. 20, 23

- ^ Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, p. 520

- ^ Culik & Kari 1997

- ^ Wang 1961

- ^ Robert Berger at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ a b c d e f g Austin 2005a

- ^ Berger 1966

- ^ Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, p. 584

- ^ Gardner 1997, p. 5

- ^ Robinson 1971

- ^ Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, p. 525

- ^ a b Senechal 1996, pp. 173–174

- ^ Penrose 1974

- ^ Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, section 2.5

- ^ Kepler, Johannes (1997). The harmony of the world. American Philosophical Society. p. 108. ISBN 0-87169-209-0.

- ^ Luck 2000

- ^ a b Senechal 1996, p. 171

- ^ a b Gardner 1997, p. 6

- ^ Gardner 1997, p. 19

- ^ a b Gardner 1997, chapter 1

- ^ de Bruijn 1981

- ^ Baake, M.; Kramer, P.; Schlottmann, M.; Zeidler, D. (December 1990). "Planar Patterns with Fivefold Symmetry as Sections of Periodic Structures in 4-Space". International Journal of Modern Physics B. 04 (15n16): 2217–2268. Bibcode:1990IJMPB...4.2217B. doi:10.1142/S0217979290001054.

- ^ The P1–P3 notation is taken from Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, section 10.3

- ^ Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, section 10.3

- ^ a b Veritasium (30 September 2020). The Infinite Pattern That Never Repeats. Retrieved 22 October 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b Penrose 1978, p. 32

- ^ "However, as will be explained momentarily, differently colored pentagons will be considered to be different types of tiles." Austin 2005a; Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, figure 10.3.1, shows the edge modifications needed to yield an aperiodic set of prototiles.

- ^ "The rhombus of course tiles periodically, but we are not allowed to join the pieces in this manner." Gardner 1997, pp. 6–7

- ^ a b c d e Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, pp. 537–547

- ^ a b Senechal 1996, p. 173

- ^ a b Gardner 1997, p. 8

- ^ Gardner 1997, pp. 10–11

- ^ Gardner 1997, p. 12

- ^ Senechal 1996, p. 178

- ^ "The Penrose Tiles". Murderous Maths. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ Gardner 1997, p. 9

- ^ Gardner 1997, p. 27

- ^ Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, p. 543

- ^ In Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, the term "inflation" is used where other authors would use "deflation" (followed by rescaling). The terms "composition" and "decomposition", which many authors also use, are less ambiguous.

- ^ Ramachandrarao, P (2000). "On the fractal nature of Penrose tiling" (PDF). Current Science. 79: 364.

- ^ Grünbaum & Shephard 1987, p. 546

- ^ Senechal 1996, pp. 157–158

- ^ a b c d e Austin 2005b

- ^ a b Senechal 1996, p. 183

- ^ Gardner 1997, p. 7

- ^ "... any finite patch that we choose in a tiling will lie inside a single inflated tile if we continue moving far enough up in the inflation hierarchy. This means that anywhere that tile occurs at that level in the hierarchy, our original patch must also occur in the original tiling. Therefore, the patch will occur infinitely often in the original tiling and, in fact, in every other tiling as well." Austin 2005a

- ^ a b Lord & Ranganathan 2001

- ^ Gummelt 1996

- ^ Steinhardt & Jeong 1996; see also Steinhardt, Paul J. "A New Paradigm for the Structure of Quasicrystals". Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ^ Colbrook; Roman; Hansen (2019). "How to Compute Spectra with Error Control". Physical Review Letters. 122 (25) 250201. Bibcode:2019PhRvL.122y0201C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.250201. PMID 31347861. S2CID 198463498.

- ^ Luck, R (1990). "Penrose Sublattices". Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids. 117–8 (90): 832–5. Bibcode:1990JNCS..117..832L. doi:10.1016/0022-3093(90)90657-8.

- ^ Lançon & Billard 1988

- ^ Godrèche & Lançon 1992; see also Dirk Frettlöh; F. Gähler & Edmund Harriss. "Binary". Tilings Encyclopedia. Department of Mathematics, University of Bielefeld.

- ^ Zaslavskiĭ et al. 1988; Makovicky 1992

- ^ Prange, Sebastian R.; Peter J. Lu (1 September 2009). "The Tiles of Infinity". Saudi Aramco World. Aramco Services Company. pp. 24–31. Archived from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ^ Lu & Steinhardt 2007

- ^ Rinaldi, Ray Mark (12 July 2019). "Two dueling Clark Richert exhibitions explore the career of one of Colorado's biggest painters". The Denver Post. Denver, Colorado. Retrieved 27 March 2025.

- ^ Kemp 2005

- ^ The Penrose Tiling at Miami University Archived 14 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine by David Kullman, Presented at the Mathematical Association of America Ohio Section Meeting Shawnee State University, 24 October 1997

- ^ "Indian Institute of Information Technology, Allahabad". ArchNet.

- ^ "Centenary: The University of Western Australia". www.treasures.uwa.edu.au.

- ^ "New Building Project". Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ "Roger Penrose explains the mathematics of the Penrose Paving". University of Oxford Mathematical Institute.

- ^ "Keskuskadun kävelykadusta voi tulla matemaattisen hämmästelyn kohde". Helsingin Sanomat. 6 August 2014.

- ^ Kuchar, Sally (11 July 2013). "Check Out the Proposed Skin for the Transbay Transit Center". Curbed.

References

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Berger, R. (1966). The undecidability of the domino problem. Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society. Vol. 66. ISBN 978-0-8218-1266-2..

- de Bruijn, N. G. (1981). "Algebraic theory of Penrose's non-periodic tilings of the plane, I, II" (PDF). Indagationes Mathematicae. 43 (1): 39–66. doi:10.1016/1385-7258(81)90017-2..

- Gummelt, Petra (1996). "Penrose tilings as coverings of congruent decagons". Geometriae Dedicata. 62 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1007/BF00239998. MR 1400977. Zbl 0893.52011.

- Penrose, Roger (1974). "The role of aesthetics in pure and applied mathematical research". Bulletin of the Institute of Mathematics and Its Applications. 10: 266ff..

- US 4133152, Penrose, Roger, "Set of tiles for covering a surface", published 9 January 1979.

- Robinson, R.M. (1971). "Undecidability and non-periodicity for tilings of the plane". Inventiones Mathematicae. 12 (3): 177–190. Bibcode:1971InMat..12..177R. doi:10.1007/BF01418780. S2CID 14259496..

- Schechtman, D.; Blech, I.; Gratias, D.; Cahn, J.W. (1984). "Metallic Phase with long-range orientational order and no translational symmetry". Physical Review Letters. 53 (20): 1951–1953. Bibcode:1984PhRvL..53.1951S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.1951.

- Wang, H. (1961). "Proving theorems by pattern recognition II". Bell System Technical Journal. 40: 1–42. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1961.tb03975.x..

Secondary sources

[edit]- Austin, David (2005a). "Penrose Tiles Talk Across Miles". Providence: American Mathematical Society..

- Austin, David (2005b). "Penrose Tilings Tied up in Ribbons". Providence: American Mathematical Society..

- Colbrook, Matthew; Roman, Bogdan; Hansen, Anders (2019). "How to Compute Spectra with Error Control". Physical Review Letters. 122 (25) 250201. Bibcode:2019PhRvL.122y0201C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.250201. PMID 31347861. S2CID 198463498.

- Culik, Karel; Kari, Jarkko (1997). "On aperiodic sets of Wang tiles". Foundations of Computer Science. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 1337. pp. 153–162. doi:10.1007/BFb0052084. ISBN 978-3-540-63746-2.

- Gardner, Martin (1997). Penrose Tiles to Trapdoor Ciphers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-88385-521-8.. (First published by W. H. Freeman, New York (1989), ISBN 978-0-7167-1986-1.)

- Chapter 1 (pp. 1–18) is a reprint of Gardner, Martin (January 1977). "Extraordinary non-periodic tiling that enriches the theory of tiles". Scientific American. Vol. 236, no. 1. pp. 110–121. Bibcode:1977SciAm.236a.110G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0177-110..

- Godrèche, C; Lançon, F. (1992). "A simple example of a non-Pisot tiling with five-fold symmetry". Journal de Physique I. 2 (2): 207–220. Bibcode:1992JPhy1...2..207G. doi:10.1051/jp1:1992134. S2CID 120168483..

- Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, G. C. (1987). Tilings and Patterns. New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-1193-3..

- Kemp, Martin (2005). "Science in culture: A trick of the tiles". Nature. 436 (7049): 332. Bibcode:2005Natur.436..332K. doi:10.1038/436332a..

- Lançon, Frédéric; Billard, Luc (1988). "Two-dimensional system with a quasi-crystalline ground state" (PDF). Journal de Physique. 49 (2): 249–256. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.700.3611. doi:10.1051/jphys:01988004902024900. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2009..

- Lord, E.A.; Ranganathan, S. (2001). "The Gummelt decagon as a 'quasi unit cell'" (PDF). Acta Crystallographica. A57 (5): 531–539. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.614.3786. doi:10.1107/S0108767301007504. PMID 11526302. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- Lu, Peter J.; Steinhardt, Paul J. (2007). "Decagonal and Quasi-crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture" (PDF). Science. 315 (5815): 1106–1110. Bibcode:2007Sci...315.1106L. doi:10.1126/science.1135491. PMID 17322056. S2CID 10374218..

- Luck, R. (2000). "Dürer-Kepler-Penrose: the development of pentagonal tilings". Materials Science and Engineering. 294 (6): 263–267. doi:10.1016/S0921-5093(00)01302-2..

- Makovicky, E. (1992). "800-year-old pentagonal tiling from Maragha, Iran, and the new varieties of aperiodic tiling it inspired". In I. Hargittai (ed.). Fivefold Symmetry. Singapore–London: World Scientific. pp. 67–86. ISBN 978-981-02-0600-0..

- Penrose, Roger (1978). "Pentaplexity" (PDF). Eureka. Vol. 39. pp. 16–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2021.. (Page numbers cited here are from the reproduction as Penrose, R. (1979–80). "Pentaplexity: A class of non-periodic tilings of the plane". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 2: 32–37. doi:10.1007/BF03024384. S2CID 120305260..)

- Radin, Charles (April 1996). "Book Review: Quasicrystals and geometry" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 43 (4): 416–421.

- Senechal, Marjorie (1996). Quasicrystals and geometry. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57541-6..

- Steinhardt, Paul J.; Jeong, Hyeong-Chai (1996). "A simpler approach to Penrose tiling with implications for quasicrystal formation". Nature. 382 (1 August): 431–433. Bibcode:1996Natur.382..431S. doi:10.1038/382431a0. S2CID 4354819..

- Zaslavskiĭ, G.M.; Sagdeev, Roal'd Z.; Usikov, D.A.; Chernikov, A.A. (1988). "Minimal chaos, stochastic web and structures of quasicrystal symmetry". Soviet Physics Uspekhi. 31 (10): 887–915. Bibcode:1988SvPhU..31..887Z. doi:10.1070/PU1988v031n10ABEH005632..

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Penrose Tiles". MathWorld.

- John Savard. "Penrose Tilings". quadibloc.com. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- Eric Hwang. "Penrose Tiling". intendo.net. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- F. Gähler; E. Harriss & D. Frettlöh. "Penrose Rhomb". Tilings Encyclopedia. Department of Mathematics, University of Bielefeld. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- Kevin Brown. "On de Bruijn Grids and Tilings". mathpages.com. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- David Eppstein. "Penrose Tiles". The Geometry Junkyard. ics.uci.edu/~eppstein. Retrieved 28 November 2009. This has a list of additional resources.

- William Chow. "Penrose tile in architecture". Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- "Penrose's tiles viewer".

Penrose tiling

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Tilings

Periodic Tilings

A periodic tiling is a covering of the Euclidean plane by non-overlapping tiles such that the entire pattern is invariant under translations by a discrete set of vectors forming a lattice, ensuring the design repeats indefinitely without gaps or overlaps.[7] This lattice generates the translation symmetries of the tiling, allowing any portion of the pattern to be reproduced elsewhere by shifting along basis vectors.[8] Mathematically, the symmetry group of a periodic tiling includes a discrete, rank-two abelian subgroup isomorphic to , generated by two linearly independent translation vectors that span the lattice.[7] This group acts freely on the plane, preserving the tiling's structure and ensuring uniformity across infinite repetitions.[9] Classic examples include the square grid, where unit squares form a lattice with basis vectors along the axes, creating a simple rectangular unit cell; the triangular lattice, composed of equilateral triangles meeting six at each vertex, with a rhombus or hexagon as the unit cell; and the hexagonal tiling, using regular hexagons with three meeting at each vertex, repeatable via a parallelogram unit cell.[8] These monohedral tilings, using a single tile shape, illustrate how periodic arrangements achieve complete plane coverage through modular repetition.[10] Periodic tilings have appeared in human art since antiquity, with Mesopotamian clay cone mosaics from around 3000 BCE employing repeating geometric motifs for decorative walls, and Roman floor mosaics from the 1st century BCE featuring tessellated patterns of squares and triangles.[11] In medieval Islamic architecture, such as the 14th-century decorations at the Topkapi Palace, artisans crafted intricate periodic girih tilings using interlocking stars and polygons, often based on square or hexagonal lattices, to adorn mosques and madrasas. These historical applications highlight periodic tilings' role in achieving aesthetic harmony through symmetry and repetition, contrasting with aperiodic tilings that lack such lattice-based periodicity.[11]Aperiodic Tilings

Aperiodic tilings represent a class of plane coverings where a finite set of prototiles can cover the infinite plane without gaps or overlaps, but every such covering lacks translational periodicity, meaning no non-trivial translation vector exists that maps the entire tiling onto itself.[12] This property contrasts with periodic tilings, which repeat a fundamental domain indefinitely under translation, and highlights the counterintuitive possibility that local matching rules enforced by tile edges can force global disorder. The concept emerged from efforts to understand whether finite tile sets obeying strict adjacency rules necessarily produce repeatable patterns. The theoretical foundations trace to Hao Wang's 1961 introduction of Wang tiles—unit squares with colored edges that must match when adjacent—and his conjecture that any set of such tiles capable of tiling the plane must admit a periodic tiling. This assumption aligned with the intuition that local constraints imply global order, akin to the periodicity in crystallographic structures. However, in 1966, Robert Berger refuted the conjecture by proving the undecidability of the domino problem—determining whether a given tile set tiles the plane—and, in the process, constructed the first aperiodic set consisting of 20,426 Wang tiles, demonstrating that aperiodicity could arise from computability reductions simulating Turing machine computations. Subsequent refinements reduced the size of aperiodic sets significantly. In 1971, Raphael Robinson streamlined Berger's approach and developed an aperiodic tile set of 6 prototiles, proving nonperiodicity through hierarchical structures that enforce infinite growth without repetition.[12] Independently in the early 1970s, Robert Ammann devised several smaller aperiodic sets, including one with 16 tiles using linear markings (Ammann bars) to propagate non-periodic constraints across the plane, as later formalized and proven aperiodic. These constructions, building on Wang tiles, established that aperiodicity requires only modest numbers of prototiles. The existence of aperiodic tile sets upends the classical view that finite local rules suffice for global periodicity, with profound implications for fields like quasicrystals in materials science, where atomic arrangements mimic such tilings, and computability theory, where they encode undecidable problems.[12] This challenges assumptions in pattern formation, showing that complexity can emerge inevitably from simple rules without periodic symmetry.Historical Development

Early Discoveries in Aperiodic Sets

In 1966, Robert Berger proved the undecidability of the domino problem—the question of whether a given set of Wang tiles can tile the plane—by constructing the first known aperiodic set of tiles, consisting of 20,426 Wang tiles with colored edges that enforce matching rules.[13] This set tiles the plane completely but admits no periodic tiling, demonstrating that algorithmic determination of tilability is impossible in general.[14] Berger's construction relied on simulating Turing machine computations through tile placements, where edge colors propagate information to prevent periodic arrangements.[14] Building on Berger's work, Raphael Robinson simplified the proof of aperiodicity and undecidability in 1971 by introducing a smaller aperiodic set of six prototiles, each a square with specific markings on the corners to enforce local matching rules and propagate hierarchical structures.[15] These markings create "influences" that force tiles to align in increasingly larger squares, ensuring non-periodicity while allowing infinite tilings.[16] Robinson's innovation reduced the complexity dramatically from Berger's thousands of tiles, shifting focus toward more manageable prototile sets that incorporate internal rules beyond simple edge colors.[17] Subsequent efforts in the late 1970s and 1990s further minimized aperiodic sets while refining matching mechanisms. In 1978, Robert Ammann developed an aperiodic set of 16 Wang tiles, using edge colors derived from substitutions in octagonal tilings to enforce aperiodicity through forced expansions.[18] This was followed in 1996 by Jarkko Kari's construction of a 14-tile aperiodic Wang set, based on simulating Beatty sequences via finite automata encoded in tile colors, which generate irrational rotations incompatible with periodicity.[19] Shortly thereafter, Karel Culik II refined Kari's approach to produce the smallest known Wang tile set at the time, with 13 tiles over five colors, again using automaton-based rules to simulate non-periodic dynamics.[20] In 2015, Emmanuel Jeandel and Michael Rao further reduced the minimum to 11 tiles over four colors, and proved by exhaustive search that no smaller aperiodic Wang tile set exists.[21] These reductions marked a conceptual evolution from Berger's computationally intensive rectangular tiles to prototiles with sophisticated edge or marking rules that embed aperiodic order through local constraints and global hierarchies.[18]Penrose's Innovations

Roger Penrose, a British mathematical physicist, developed his groundbreaking aperiodic tilings during the 1970s, motivated by the challenge of achieving fivefold rotational symmetry in plane tilings, which is impossible in periodic lattices due to crystallographic restrictions. His work was influenced by the intricate tessellations of artist M.C. Escher, whose prints explored impossible geometries and non-repeating patterns, inspiring Penrose to seek tile sets that enforced aperiodicity while exhibiting local fivefold symmetry.[22][23] In 1974, Penrose published his initial aperiodic tile set in the paper "The rôle of aesthetics in pure and applied mathematical research," consisting of six prototiles based on pentagonal shapes with specific markings to enforce matching rules and prevent periodic arrangements. This set represented a significant simplification over earlier abstract aperiodic constructions, such as those using large numbers of Wang tiles, by prioritizing aesthetic and symmetry-driven designs that were visually compelling yet mathematically rigorous. Penrose later refined this approach, reducing the number of prototiles while preserving aperiodicity.[24][3] A major breakthrough came in 1978 with Penrose's publication "Pentaplexity" in Eureka, where he introduced a minimal set of two rhombi (known as the P3 tiling) whose edge markings ensured only non-periodic tilings of the plane, further streamlining the construction to emphasize golden ratio proportions and fivefold symmetry. Around the same time, he independently formulated the kite and dart pair (P2 tiling), another two-tile system that achieves the same aperiodic properties through concave and convex shapes with matching rules. These innovations built on complex precursors from prior aperiodic set research but made the concept accessible through simple, symmetry-focused geometries.[25][4] Penrose's tilings gained widespread recognition through his collaboration with science writer Martin Gardner, who popularized them in Scientific American articles starting in 1977 and in the 1989 book Penrose Tiles to Trapdoor Ciphers, bridging mathematical theory with public interest. Notably, Penrose's work predated the 1982 experimental discovery of quasicrystals by Dan Shechtman—real materials exhibiting aperiodic order with fivefold symmetry—providing a theoretical framework that helped interpret these findings as projections of higher-dimensional lattices.[26]Specific Penrose Tilings

Original Pentagonal Tiling (P1)

The original pentagonal tiling, designated as P1, was developed by Roger Penrose as an early approach to constructing aperiodic tilings exhibiting fivefold symmetry. It relies on a set of six prototiles featuring specific edge markings known as junctures, which dictate compatible adjacencies to prevent periodic arrangements. These junctures consist of curved lines or arcs drawn on the edges of the prototiles, ensuring that only matching configurations can join, thereby enforcing local rules that propagate globally.[27] The prototiles consist of irregular pentagons along with derived shapes such as the boat, star (pentagram), rhombus, and additional pentagon variants, all incorporating the golden ratio in their proportions for compatibility. These six distinct prototiles arise from basic forms with rotational symmetries and specific juncture placements, allowing for precise control over tiling assembly.[1] Assembly begins with small clusters of these prototiles, where edges must align such that junctures form continuous paths without breaks or overlaps. Compatible prototiles fit together to form supertiles—larger composite units with outlines approximating regular decagons—demonstrating local pentagonal symmetry. For instance, a basic supertile might consist of five prototiles surrounding a central one, their junctures interlocking to create a star-like decagonal boundary. A small patch of such a tiling reveals radiating fivefold symmetries, with prototiles arranged in rosettes that echo the decagonal form.[27] The tiling's aperiodicity is enforced through hierarchical clustering, where supertiles serve as building blocks for even larger decagonal structures, creating an infinite regress of scales centered on decagonal stars. This self-similar hierarchy, driven by the juncture rules, precludes translational periodicity, as any periodic repetition would disrupt the required decagonal alignments at higher levels. Penrose's innovations in this tiling laid the foundation for subsequent aperiodic sets by demonstrating how local constraints could globally prohibit repetition.[1]Kite and Dart Tiling (P2)

The kite and dart tiling, designated as P2, is one of Roger Penrose's aperiodic tilings using just two prototiles: the kite and the dart. The kite is a convex quadrilateral with interior angles measuring 72°, 72°, 72°, and 144°, arranged such that the 144° angle is opposite the longest diagonal. The dart is a non-convex quadrilateral (concave at one vertex) with interior angles of 72°, 36°, 72°, and 216°, where the 216° reflex angle creates the indentation. Both prototiles feature edges of two distinct lengths, with the ratio of longer to shorter sides equal to the golden ratio φ = (1 + √5)/2 ≈ 1.618, typically normalized so short edges measure 1 and long edges measure φ; this proportion embeds fivefold symmetry locally while ensuring global aperiodicity.[28][29] To generate valid tilings, the prototiles must adhere to strict edge-matching rules that align concave and convex vertices correctly, thereby forbidding periodic configurations. These rules are commonly implemented via decorations on the tiles, such as bicolored vertices (e.g., black and white markings) that must match at shared edges or directed arrows along edges indicating orientation and type, ensuring that only compatible juxtapositions occur—such as a convex 72° vertex of a kite meeting the concave 216° vertex of a dart in specific ways. Without these enforcements, periodic tilings become possible, but the rules restrict assemblies to aperiodic ones, promoting hierarchical growth.[30][31][28] Tiling construction begins with small patches that expand hierarchically, forming characteristic supertile motifs like the "house" (a kite paired with a dart along a long edge, resembling a simple roofed structure) and the "star" (five darts converging at a central vertex, evoking a pentagram outline). These basic units combine to create larger, self-similar clusters, such as the infinite star pattern starting from five darts or the infinite sun from five kites, yielding an unending cascade of non-repeating scales that produce the illusion of fivefold rotational symmetry across the plane without true long-range order. The ratio of kites to darts in large regions approximates φ, reinforcing the tiling's intrinsic scaling properties.[3] Although the kite and dart prototiles are non-convex, the P2 tiling is topologically equivalent to Penrose's original pentagonal tiling (P1) and the rhombus tiling (P3), meaning they produce diffeomorphic coverings of the plane with identical local isomorphism classes under the matching rules, but P2's concave darts allow for smoother, more fluid boundaries in finite approximations compared to the rigid pentagons of P1.[28]Rhombus Tiling (P3)

The rhombus tiling, designated as P3 in Penrose's classification, employs two prototiles: a thin rhombus with interior angles of 36° and 144°, and a thick rhombus with angles of 72° and 108°. Both prototiles are rhombi with equal side lengths, and their diagonals stand in the golden ratio , where the longer diagonal exceeds the shorter by this irrational proportion. This geometric relation ties the tiles intrinsically to five-fold symmetry, as the angles derive from divisions of the 360° circle by 5 and 10, facilitating non-periodic arrangements.[32][31] To enforce aperiodicity, matching rules govern tile adjacency, typically implemented via directed arrows or indentations on edges that must align precisely—such as head-to-tail vector matching or compatible markings. These constraints prevent periodic repetitions and naturally generate hierarchical supertiles, including the characteristic "sun" (a central thick rhombus surrounded by five thin ones) and "star" (a five-pointed configuration of alternating rhombi) patterns, which serve as building blocks for larger structures.[33][34] The convex nature of these rhombi offers practical advantages for physical realizations, as they can be more readily fabricated from materials like wood or metal without concave cuts, unlike alternative representations. Moreover, the rhombus tiling is mutually equivalent to the kite and dart tiling (P2), achievable by subdividing each thick rhombus into a kite and a half-kite, and each thin rhombus into two half-kites and a dart, preserving the aperiodic properties under this transformation.[31][35] A notable example is finite patches of the rhombus tiling that approximate the infinite star pattern, a supertile exhibiting prominent five-fold rotational symmetry bounded by straight edges, demonstrating how local rules propagate global aperiodicity.[3]Core Mathematical Features

Golden Ratio Integration

The golden ratio, denoted φ and defined as φ = (1 + √5)/2 ≈ 1.6180339887, is a fundamental irrational number that satisfies the equations φ = 1 + 1/φ and φ² = φ + 1.[3] This self-similar property, where φ appears in its own continued fraction expansion as [1;1,1,1,...], underscores its role in generating hierarchical structures without periodic repetition, a key factor in the aperiodicity of Penrose tilings.[30] The irrationality of φ prevents commensurate ratios in tile counts or dimensions, ensuring that no translational symmetry can extend infinitely across the plane.[31] In the kite and dart prototiles (P2 tiling), the golden ratio governs the edge lengths and diagonals, with short sides normalized to length 1 and long sides to length φ.[36] The kite features two adjacent short sides and two long sides, with its long diagonal of length φ and short diagonal of length 1; the dart mirrors this but is concave, sharing the same side and diagonal ratios of 1:φ.[3] These proportions derive from subdividing a regular pentagon, where the diagonal-to-side ratio is precisely φ, enabling the tiles to approximate fivefold symmetry locally.[37] For the rhombus prototiles (P3 tiling), the thin rhombus has acute angles of 36° and obtuse angles of 144°, while the thick rhombus has 72° and 108° angles, both sets derived from divisions of the 72° central angle in a regular pentagon (360°/5 = 72°).[37] All edges are of equal length, but the diagonals follow the 1:φ ratio, with the longer diagonal spanning φ times the shorter one, mirroring the kite and dart geometry.[36] For explicit ratios in the dart, if the width (short diagonal) is set to 1, the length (long diagonal) equals φ, ensuring compatibility in assemblies.[3] The integration of φ extends to scaling in Penrose tilings, where inflation enlarges linear dimensions by a factor of φ and areas by φ² ≈ 2.618, preserving the overall structure while introducing finer hierarchical details.[38] This scaling reflects the continued fraction nature of φ, allowing infinite subdivision without periodicity.[30]Local Pentagonal Symmetry

Penrose tilings demonstrate local pentagonal symmetry through clusters of tiles that form decagonal or star-shaped patterns exhibiting fivefold rotational symmetry of 72 degrees around specific vertices, while the entire structure remains aperiodic without a repeating lattice. These local configurations arise naturally from the tile geometries and matching rules, allowing finite patches to mimic the symmetry of a regular decagon or pentagram, but such patterns cannot extend infinitely without defects in a periodic setting.[3] In the rhombus tiling variant (P3), vertex figures reveal this symmetry through 7 distinct types of local arrangements, each involving pentagonal coordination where tiles meet at angles derived from multiples of 72 degrees. These vertex types ensure that the local environment around each point maintains fivefold rotational invariance up to a finite radius, contributing to the tiling's quasiperiodic character.[39] Fivefold rotational symmetry proves incompatible with translational periodicity in the plane because the irrational rotation angles, rooted in the golden ratio, cannot align with a lattice's rational translational vectors, leading to unavoidable mismatches over large distances.[40] Diffraction patterns from Penrose tilings further highlight this local symmetry, producing discrete Bragg peaks arranged in a 10-fold symmetric array that reflects the underlying quasiperiodicity without implying long-range order.[40]Construction Techniques

Inflation Procedures

The inflation procedure for Penrose tilings is a generative method that constructs larger supertiles by subdividing each prototile into a cluster of smaller copies of the prototiles, scaled by a linear factor of the golden ratio , resulting in an area increase by per iteration.[33] This self-similar substitution rule ensures that repeated applications produce increasingly complex tilings while inherently enforcing the aperiodic structure through the geometric constraints of the prototiles.[4] In the kite and dart tiling (P2), the inflation rule specifies that each kite supertile is decomposed into two smaller kites and two smaller half-darts, while each dart supertile is decomposed into one smaller kite and two smaller half-darts. These substitutions maintain edge-to-edge matching and cover the original tile without gaps or overlaps, with the overall pattern expanding hierarchically (the half-darts pair with adjacent tiles to form full darts).[41] For the rhombus tiling (P3), which uses a thin rhombus (with angles and ) and a thick rhombus (with angles and ), the inflation proceeds as follows: the thin rhombus subdivides into two smaller thin rhombi and one smaller thick rhombus, whereas the thick rhombus subdivides into two smaller thick rhombi and one smaller thin rhombus.[33] This process similarly scales by linearly, preserving the decagonal symmetry and aperiodic ordering. The hierarchical nature of inflation allows tilings to be generated iteratively from a finite seed patch, such as a single prototile or a small valid cluster, through infinite subdivisions that fill the plane densely while prohibiting periodic arrangements due to the irrational scaling factor .[1] This method underscores the self-similarity inherent in Penrose tilings, where each level reveals patterns that mirror the whole at larger scales.[4]Deflation and Decomposition Methods

Deflation serves as the inverse process to inflation in Penrose tilings, enabling the systematic decomposition of a given tiling by identifying and grouping clusters of smaller prototiles to form larger supertiles according to the reverse of the inflation substitution rules. This method allows analysts to reduce any valid Penrose tiling iteratively, confirming its adherence to the underlying aperiodic structure by converging to the original set of prototiles, such as kites and darts or thin and thick rhombi. Unlike inflation, which builds hierarchical supertiles from basic tiles by subdivision, deflation groups tiles to verify consistency across scales, often revealing the unique prototile set regardless of the starting configuration.[3] In the kite and dart tiling (P2), deflation proceeds by identifying supertile boundaries and grouping: a larger kite is formed from two smaller kites and two smaller half-darts (pairing to one full dart), while a larger dart is formed from one smaller kite and two smaller half-darts; these groupings are scaled by the factor in area, where is the golden ratio, ensuring the areas match and the process tiles the plane without gaps or overlaps. For the rhombus tiling (P3), a similar approach applies: a larger thin rhombus is composed of two smaller thin rhombi and one smaller thick rhombus, and a larger thick rhombus of one smaller thin rhombus and two smaller thick rhombi, again scaled by , with supertile boundaries delineated by tracing edges that align with the inflation rules in reverse. Repeated application of these steps on any finite or infinite valid tiling converges to the fundamental prototile set, demonstrating the self-similar nature of the structure.[41][33] A key decomposition technique involves breaking down Penrose prototiles into Robinson triangles, named after Raphael M. Robinson, who introduced them as an auxiliary tool for analyzing aperiodic tilings. These are two types of isosceles triangles: the "acute" triangle with angles 36°, 72°, and 72°, and the "obtuse" triangle with angles 108°, 36°, and 36°. In the rhombus tiling (P3), each thin rhombus is composed of two acute triangles joined along their long edges, while each thick rhombus consists of one acute and one obtuse triangle similarly joined; for the kite and dart tiling (P2), the kite divides into two acute triangles, and the dart into one acute and one obtuse. To decompose a full tiling, one draws the short diagonals across each prototile to separate them into these triangles, then applies deflation rules to the triangles themselves—such as grouping for the reverse of subdividing the acute triangle into two acute and two obtuse smaller ones, and the obtuse into two acute and one obtuse—scaled appropriately to maintain the hierarchy. This triangular breakdown facilitates precise boundary identification and subdivision at each level.[12] The deflation and decomposition methods, particularly via Robinson triangles, provide a practical means to verify that local matching rules in Penrose tilings propagate consistently to global scales, as iterative reduction ensures no inconsistencies arise in the hierarchical structure without invoking full aperiodicity arguments. By repeatedly deflating, one can trace how edge markings or vertex constraints enforced locally extend through supertile levels, confirming the tiling's validity and uniqueness within the aperiodic family.[4]Matching Rules and Enforcement

Matching rules in Penrose tilings consist of local constraints on how tile edges or vertices must align to form valid configurations, ensuring that only aperiodic tilings can cover the plane without gaps or overlaps. These rules can be realized through several mechanisms, including edge vectors where directional arrows on tile edges must sum to zero at every vertex, color matchings requiring adjacent edges to share the same color designation, or physical notches that permit interlocking only in approved orientations.[42][4] In the kite and dart tiling (P2), matching rules are enforced by specific geometric features: the dart's concave edge fits precisely into the kite's corresponding convex edge, while additional markings—such as aligned arcs or lines on edges—dictate permissible adjacencies. These rules designate distinct vertex types, including "sun" vertices where five kites converge and "star" vertices where five darts meet, alongside mixed configurations that maintain local fivefold symmetry. Local prohibitions, such as barring two darts from adjoining along their long edges, further constrain placements.[43][44] Such local rules enforce an infinite hierarchical structure, as satisfying them at one scale necessitates consistent patterns at progressively larger scales, inherently precluding periodic arrangements. Deflation serves as a verification tool to confirm adherence by breaking down the tiling into constituent prototiles. Consequently, every valid tiling under these rules adheres to the underlying inflation framework, guaranteeing aperiodicity across all possible configurations.[45][27]Properties and Implications

Global Aperiodicity Proofs

Global aperiodicity proofs for Penrose tilings demonstrate that no valid tiling by kite and dart (P2) or thin and thick rhombi (P3) prototiles can exhibit translational periodicity, relying on the inherent role of the golden ratio and the hierarchical structure induced by inflation and deflation rules.[31] A foundational argument assumes a periodic tiling exists with some finite translation vector, implying that the entire plane can be covered by repeating a fundamental domain. However, the inflation procedure scales tile sizes by powers of , which is irrational, leading to supertile positions that cannot align periodically without contradicting the irrational scaling factors. Specifically, if a tiling were periodic, the relative frequencies of tile types (such as the ratio of thick to thin rhombi approaching ) would be rational, but the irrationality of ensures this ratio remains irrational, deriving a contradiction.[31] The hierarchy argument employs deflation, the inverse of inflation, to show infinite descent is possible only in non-periodic tilings. In a valid Penrose tiling, repeated deflation decomposes larger supertiles into smaller ones indefinitely, creating an infinite hierarchy of scales without reaching a base case that could repeat periodically.[31] If periodicity held, deflation would eventually map the fundamental domain to a finite set of prototiles that tile periodically at every level, but the scaling by (where ) disrupts this due to the irrationality, preventing closure under a finite period.[31] This infinite regress implies no finite translational symmetry can govern the entire tiling. Formal results characterize the space of all Penrose tilings as a fiber bundle over the 2-torus with Cantor set fibers, where the fiber is a compact, totally disconnected perfect metric space with no isolated points, confirming the absence of any non-trivial translational symmetries. This topological structure, arising from the matching rules and substitution dynamics, ensures that while individual tilings cover the plane with uniform density (e.g., the area proportion of tile types stabilizes to values involving ), vertex positions exhibit quasiperiodic order rather than strict periodicity.[31][46]Spectral and Diffraction Analysis

The diffraction analysis of Penrose tilings treats the tiling as a point set, typically the positions of tile vertices or centers, and computes its Fourier transform to reveal the pattern's structural order. In the infinite limit, the diffraction spectrum consists of a pure point measure, characterized by sharp Bragg peaks without diffuse scattering. These peaks occur at wavevectors belonging to a dense set forming a decagonal lattice, where the positions are generated as integer combinations of basis vectors in directions rotated by multiples of , with amplitudes scaled by powers of the golden ratio . This decagonal arrangement reflects the underlying 10-fold rotational symmetry inherent in the tiling's local pentagonal features.[47] The intensity of the diffraction pattern is formally given by the formula where are the positions in the point set, and the sum is taken in the thermodynamic limit via the autocorrelation measure. For Penrose tilings constructed as model sets from a 5-dimensional cubic lattice projection, this yields Bragg peaks whose locations and relative intensities are determined by the dual module in the physical space, ensuring a hierarchically structured spectrum with intensities decaying according to the window function's Fourier transform.[47] Spectral properties of the associated dynamical system arise from the inflation (substitution) rule governing the tiling's self-similarity. The substitution matrix for the thin and thick rhombs in the P3 Penrose tiling is , with eigenvalues and . These Pisot-Vijayaraghavan eigenvalues imply a pure point spectrum for the translation dynamics on the hull of Penrose tilings, meaning the eigenfunctions form a basis of continuous functions on the tiling space, which in turn guarantees the pure point nature of the diffraction spectrum.[49][50] This spectral and diffraction behavior demonstrates how Penrose tilings emulate the long-range order of crystals in producing discrete Bragg peaks, yet incorporate forbidden rotational symmetries, thereby providing a mathematical bridge between aperiodic geometry and physical quasicrystal phenomena.[47]Extensions and Applications

Connections to Quasicrystals

In 1982, Dan Shechtman observed a diffraction pattern with 10-fold symmetry in a rapidly solidified aluminum-manganese alloy containing 14% manganese, challenging the prevailing crystallographic dogma that crystals must exhibit translational periodicity.[51] This discovery, published in 1984, revealed an icosahedral phase with long-range orientational order but no translational symmetry, which was later interpreted through the lens of Penrose tilings as a physical manifestation of aperiodic order.[52] Quasicrystals are mathematically modeled as cut-and-project sets derived from higher-dimensional periodic lattices, where a slice of the lattice is projected onto lower-dimensional space, yielding structures that approximate the aperiodic arrangements of Penrose tilings.[53] This method, introduced shortly after Shechtman's observation, provides a rigorous framework for understanding the quasiperiodic atomic arrangements in these materials, linking the discrete, non-repeating patterns of Penrose tilings to the diffuse yet sharp diffraction patterns observed experimentally.[51] Decagonal quasicrystals, such as those in the Al-Co-Ni system, serve as direct physical analogs to the pentagonal Penrose tiling (P3), where atomic clusters arrange in a quasiperiodic fashion mimicking the tiling's fivefold symmetry and local pentagonal motifs.[54] High-resolution imaging and structural refinements of Al-Co-Ni alloys confirm this correspondence, with the material's decagonal superstructure aligning to rhombic or pentagonal Penrose frameworks, demonstrating stable aperiodic order under thermodynamic conditions.[55] In recognition of this paradigm shift, Dan Shechtman was awarded the 2011 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of quasicrystals, explicitly crediting the foundational role of Penrose tilings in providing the conceptual and mathematical basis for interpreting their aperiodic structures.[56] In 2023, researchers Zhi Li and Latham Boyle demonstrated that Penrose tilings are mathematically equivalent to a form of quantum error-correcting code, where the non-repeating patterns enable safeguarding quantum information through local indistinguishability, allowing tolerance to localized errors without revealing global structure. This connection, published on arXiv in November 2023, opens applications of Penrose tilings in quantum computing and information theory.[57]Related Aperiodic Structures

The Ammann-Beenker tiling is an aperiodic tiling of the plane featuring eightfold rotational symmetry, constructed using two prototiles: a square and a rhombus with acute angles of 45 degrees.[58] These tiles are related by the silver ratio, , analogous to the role of the golden ratio in Penrose tilings, and aperiodicity is enforced through matching rules that generate a hierarchical structure without translational periodicity.[58] The tiling can be generated via substitution rules, where larger supertiles are composed of smaller ones in a self-similar fashion, ensuring non-periodic arrangements.[59] Other variants of Penrose tilings include the sphinx tiling, which uses two prototiles—a larger sphinx-shaped hexiamond and a smaller companion tile—and relies on inflation rules to produce aperiodic coverings with fivefold symmetry.[60] Similarly, the F-tiling employs two irregular pentagonal prototiles, the F-tile and another complementary shape, also admitting only non-periodic tilings through substitution methods that build infinite hierarchies. These variants, like the standard kite-and-dart or rhombus Penrose sets, demonstrate how minimal prototile counts can force aperiodicity via geometric constraints. Generalizations to three dimensions extend Penrose principles to icosahedral symmetry, using two rhombohedral prototiles: a prolate (obtuse) rhombohedron and an acute one, whose edges correspond to projections from a five-dimensional lattice.[61] Matching rules on faces ensure that valid tilings of three-dimensional space are aperiodic, forming structures analogous to two-dimensional Penrose tilings but with icosahedral point group symmetry.[61] These 3D tilings maintain hierarchical self-similarity, with supertiles decomposing into smaller copies under inflation.[62] Substitution systems for aperiodic tilings trace back to Berger's 1966 construction of an aperiodic set with over 20,000 prototiles, which used hierarchical substitutions to simulate undecidable computations and force non-periodicity. Robinson later refined this approach in 1971, developing a set of six square prototiles with markings that enforce aperiodicity through macro-tile hierarchies, where larger squares contain smaller ones in a non-repeating pattern.[16] Kari's contributions include a 1996 aperiodic set of 14 Wang tiles, where edge colors simulate multiplication of irrational Beatty sequences via Mealy machines, ensuring only non-periodic tilings are possible.[19] These structures, including the Ammann-Beenker and Penrose variants, enforce aperiodicity through similar hierarchical substitution rules that propagate local constraints globally, preventing periodic repetitions.[58] However, they differ in underlying symmetry: Penrose tilings exhibit decagonal (fivefold) symmetry, while Ammann-Beenker features octagonal (eightfold) symmetry, and 3D extensions introduce icosahedral symmetry, each tied to distinct irrational ratios like the golden or silver mean.[59] Berger, Robinson, and Kari's systems emphasize computational undecidability via tile markings, contrasting with the geometric focus of Ammann and Penrose but sharing the core mechanism of infinite, non-repeating hierarchies.[19]Implementations in Art and Design

Penrose tilings have inspired numerous artistic works, particularly those drawing from the visual motifs of M.C. Escher, whose tessellations influenced Roger Penrose's development of aperiodic patterns in the 1970s. Escher, in turn, incorporated modified Penrose rhombi into his final tessellation artwork, creating intricate, non-repeating designs that blend mathematical precision with optical illusion.[23] This mutual influence led to exhibitions such as "Nadir and Zenith in the World of Escher," which featured Penrose tilings alongside Escher's prints to highlight their shared exploration of symmetry and infinity.[23] Digital generations of Penrose patterns have further expanded this artistic legacy, with artists using software to produce infinite, non-periodic motifs for prints and installations, as seen in works exhibited at the Bridges Conference on mathematical art.[63] In architecture, Penrose tilings offer a visually dynamic alternative to periodic patterns, often implemented using the rhombus variant for its relative ease in physical construction. Early installations appeared in the 1980s, including floor pavings in academic buildings that showcased the tilings' fivefold symmetry.[64] Notable examples include the courtyard tiling at Miami University's Bachelor Hall, completed in the late 1980s as an artistic and educational feature demonstrating aperiodic order.[64] More recent applications extend to facades and public spaces, such as the stone and clay Penrose rhombus flooring outside the Mathematical Institute at the University of Oxford, which creates an unpredictable yet harmonious surface.[65] Similarly, the entrance paving at the Simons Center for Geometry and Physics at Stony Brook University employs Penrose tiles to evoke mathematical elegance in a built environment.[66] Roger Penrose secured a patent in 1979 for a set of two rhombus-shaped tiles designed to produce non-periodic coverings, intended for applications in manufacturing, flooring, and decorative surfaces to ensure unique, non-repeating patterns that resist straightforward replication.[67] This patent, titled "Set of tiles for covering a surface," emphasized the tiles' ability to form aperiodic tilings with fivefold symmetry, influencing subsequent designs in both industrial and artistic contexts.[67] The invention's focus on practical enforcement of aperiodicity through tile shapes has been cited in discussions of intellectual property for geometric designs, underscoring its role in protecting innovative patterns.[68] Contemporary implementations leverage digital fabrication for broader accessibility, including 3D-printed sculptures and jewelry that translate Penrose patterns into tangible forms. For instance, designers like Omri Revesz created the "Penrose" jewelry collection in 2016 using 3D printing to form interlocking, aperiodic motifs from nylon, allowing for lightweight, customizable pieces that capture the tiling's infinite variety.[69] Artists such as Debora Coombs and Duane Bailey have produced 3D-printed Penrose tiling sculptures, extending the two-dimensional patterns into volumetric art that explores spatial aperiodicity.[70] Software tools facilitate these creations, with open-source projects utilizing libraries like Cairo for generating scalable vector graphics of Penrose tilings, enabling precise digital prototyping for prints, jewelry, and larger installations up to 2025.[71] These modern uses highlight the tiling's enduring appeal in blending computation, craftsmanship, and aesthetic innovation.References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/386915550_Mathematical_diffraction_of_aperiodic_structures

.svg/250px-Penrose_Tiling_(Rhombi).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Penrose_Tiling_(Rhombi).svg.png)