Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Reptiliomorpha

View on Wikipedia

| Reptiliomorpha | |

|---|---|

| |

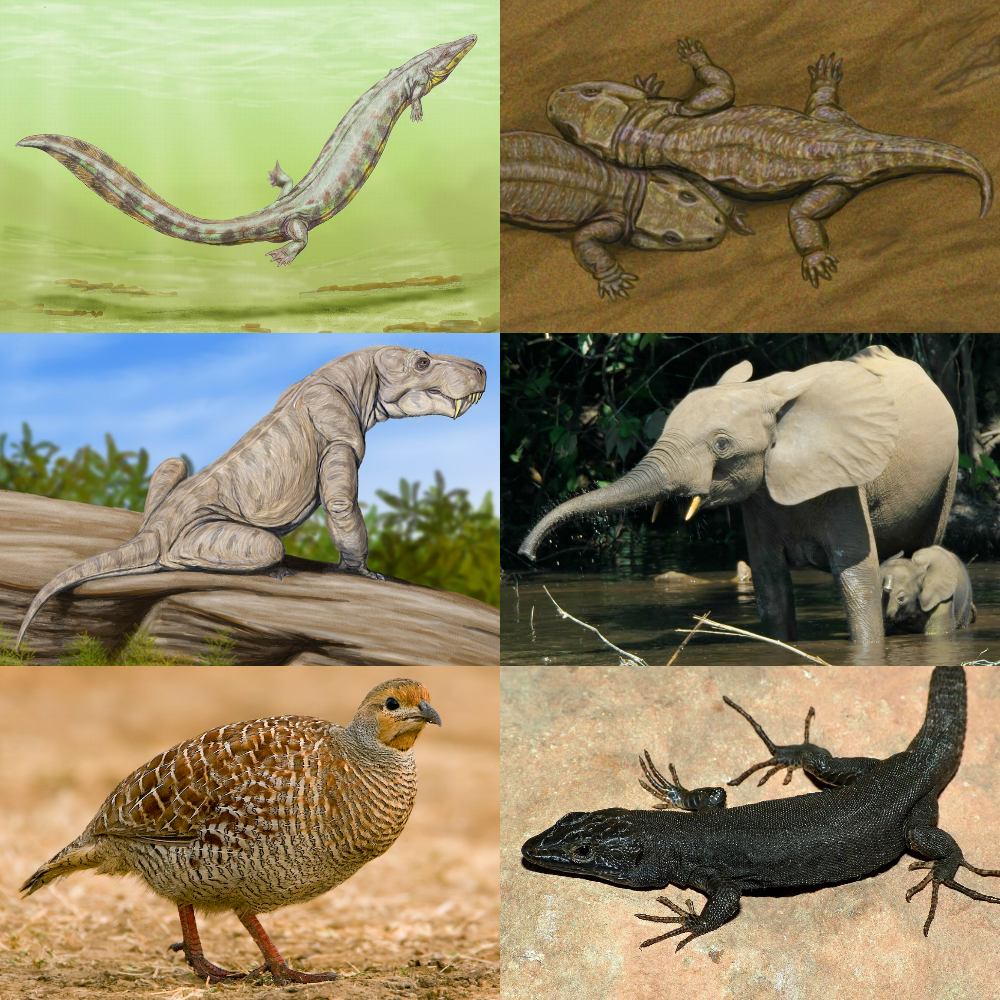

| Diversity of clade Reptiliomorpha.

1st row (stem group): Archeria crassidica, Seymouria sanjuanensis; 2nd row (Synapsida): Dinogorgon rubidgei, Loxodonta cyclotis; 3rd row (Sauropsida/Reptilia): Ortygornis pondicerianus, Podarcis muralis. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Tetrapoda |

| Clade: | Reptiliomorpha Säve-Söderbergh, 1934 |

| Subgroups | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pan-Amniota Rowe, 2004[2] | |

Reptiliomorpha (meaning reptile-shaped; in PhyloCode known as Pan-Amniota[3][4]) is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians (lissamphibians). It was defined by Michel Laurin (2001) and Vallin and Laurin (2004) as the largest clade that includes Homo sapiens, but not Ascaphus truei (tailed frog).[5][6] Laurin and Reisz (2020) defined Pan-Amniota as the largest total clade containing Homo sapiens, but not Pipa pipa, Caecilia tentaculata, and Siren lacertina.[3][4]

The informal variant of the name, "reptiliomorphs", is also occasionally used to refer to stem-amniotes, i.e. a grade of reptile-like tetrapods that are more closely related to amniotes than they are to lissamphibians, but are not amniotes themselves; the name is used in this meaning e.g. by Ruta, Coates and Quicke (2003).[7] An alternative name, "Anthracosauria", is also commonly used for the group, but is confusingly also used for a more primitive grade of reptiliomorphs (Embolomeri) by Benton.[8] While both anthracosaurs and embolomeres are suggested to be reptiliomorphs closer to amniotes, some recent studies either retain them as amphibians or argue that their relationships are still ambiguous and are more likely to be stem-tetrapods.[9][10][11]

As the exact phylogenetic position of Lissamphibia within Tetrapoda remains uncertain, it also remains controversial which fossil tetrapods are more closely related to amniotes than to lissamphibians, and thus, which ones of them were reptiliomorphs in any meaning of the word. The two major hypotheses for lissamphibian origins are that they are either descendants of dissorophoid temnospondyls or microsaurian "lepospondyls". If the former (the "temnospondyl hypothesis") is true, then Reptiliomorpha includes all tetrapod groups that are closer to amniotes than to temnospondyls. These include the diadectomorphs, seymouriamorphs, most or all "lepospondyls", gephyrostegids, and possibly the embolomeres and chroniosuchians.[7] In addition, several "anthracosaur" genera of uncertain taxonomic placement would also probably qualify as reptiliomorphs, including Solenodonsaurus, Eldeceeon, Silvanerpeton, and Casineria. However, if lissamphibians originated among the lepospondyls according to the "lepospondyl hypothesis", then Reptiliomorpha refers to groups that are closer to amniotes than to lepospondyls. Few non-amniote groups would count as reptiliomorphs under this definition, although the diadectomorphs are among those that qualify.[12]

Changing definitions

[edit]The name Reptiliomorpha was coined by Professor Gunnar Säve-Söderbergh in 1934 to designate amniotes and various types of late Paleozoic tetrapods that were more closely related to amniotes than to living amphibians. In his view, the amphibians had evolved from fish twice, with one group composed of the ancestors of modern salamanders and the other, which Säve-Söderbergh referred to as Eutetrapoda, consisting of anurans (frogs), amniotes, and their ancestors, with the origin of caecilians being uncertain. Säve-Söderbergh's Eutetrapoda consisted of two sister-groups: Batrachomorpha, containing anurans and their ancestors, and Reptiliomorpha, containing anthracosaurs and amniotes.[13] Säve-Söderbergh subsequently added Seymouriamorpha to his Reptiliomorpha as well.[14]

Alfred Sherwood Romer rejected Säve-Söderbergh's theory of a biphyletic amphibia and used the name Anthracosauria to describe the "labyrinthodont" lineage from which amniotes evolved. In 1970, the German paleontologist Alec Panchen took up Säve-Söderbergh's name for this group as having priority,[15] but Romer's terminology is still in use, e.g. by Carroll (1988 and 2002) and by Hildebrand & Goslow (2001).[16][17][18] Some writers preferring phylogenetic nomenclature use Anthracosauria.[19]

In 1956, Friedrich von Huene included both amphibians and anapsid reptiles in the Reptiliomorpha. This included the following orders: Anthracosauria, Seymouriamorpha, Microsauria, Diadectomorpha, Procolophonia, Pareiasauria, Captorhinidia, Testudinata.[20]

Michael Benton (2000, 2004) made it the sister-clade to Lepospondyli, containing "anthracosaurs" (in the strict sense, i.e. Embolomeri), seymouriamorphs, diadectomorphs and amniotes.[8] Subsequently, Benton included lepospondyls in Reptiliomorpha as well.[21] However, when considered in a Linnean framework, Reptiliomorpha is given the rank of superorder and includes only reptile-like amphibians, not their amniote descendants.[22]

Several phylogenetic studies indicate that amniotes and diadectomorphs share a more recent common ancestor with lepospondyls than with seymouriamorphs, Gephyrostegus and Embolomeri (e.g. Laurin and Reisz, 1997,[23] 1999;[12] Ruta, Coates and Quicke, 2003;[7] Vallin and Laurin, 2004;[6] Ruta and Coates, 2007[24]). Lepospondyls are one of the groups of tetrapods suggested to be ancestors of living amphibians; as such, their potential close relationship to amniotes has important implications for the content of Reptiliomorpha. Assuming that lissamphibians aren't descended from lepospondyls but from a different group of tetrapods, e.g. from temnospondyls,[7][24][25] it would mean that Lepospondyli belonged to Reptiliomorpha sensu Laurin (2001), as it would make them more closely related to amniotes than to lissamphibians. On the other hand, if lissamphibians are descended from lepospondyls,[6][23][12] then not only Lepospondyli would have to be excluded from Reptiliomorpha, but seymouriamorphs, Gephyrostegus and Embolomeri would also have to be excluded from this group, as this would make them more distantly related to amniotes than living amphibians are. In that case, the clade Reptiliomorpha sensu Laurin would contain, apart from Amniota, only diadectomorphs and possibly also Solenodonsaurus.[6]

Characteristics

[edit]Gephyrostegids, seymouriamorphs and diadectomorphs were land-based, reptile-like amphibians, while embolomeres were aquatic amphibians with long bodies and short limbs. Their anatomy falls between the mainly aquatic Devonian labyrinthodonts and the first reptiles. University of Bristol paleontologist Professor Michael J. Benton gives the following characteristics for the Reptiliomorpha (in which he includes embolomeres, seymouriamorphs and diadectomorphs):[8]

- narrow premaxillae (less than half the skull width)

- vomers taper forward

- phalangeal formulae (number of joints in each toe) of foot 2.3.4.5.4–5

Cranial morphology

[edit]The groups traditionally assigned to Reptiliomorpha, i.e. embolomeres, seymouriamorphs and diadectomorphs, differed from their contemporaries, the non-reptiliomorph temnospondyls, in having a deeper and taller skull, but retained the primitive kinesis (loose attachment) between the skull roof and the cheek (with exception of some specialized taxa, such as Seymouria, in which the cheek was solidly attached to the skull roof[26]). The deeper skull allowed for laterally placed eyes, contrary to the dorsally placed eyes commonly found in amphibians. The skulls of the group are usually found with fine radiating grooves. The quadrate bone in the back of the skull held a deep otic notch, likely holding a spiracle rather than a tympanum.[27][28]

Postcranial skeleton

[edit]

The vertebrae showed the typical multi-element construction seen in labyrinthodonts. According to Benton, in the vertebrae of "anthracosaurs" (i.e. Embolomeri) the intercentrum and pleurocentrum may be of equal size, while in the vertebrae of seymouriamorphs the pleurocentrum is the dominant element and the intercentrum is reduced to a small wedge. The intercentrum gets further reduced in the vertebrae of amniotes, where it becomes a thin plate or disappears altogether.[29] Unlike most labyrinthodonts, the body was moderately deep rather than flat, and the limbs were well-developed and ossified, indicating a predominantly terrestrial lifestyle except in secondarily aquatic groups. Each foot held five digits, the pattern seen in their amniote descendants.[30] They did, however, lack the reptilian type of ankle bone that would have allowed the use of the feet as levers for propulsion rather than as holdfasts.[31]

Physiology

[edit]

The general build was heavy in all forms, though otherwise very similar to that of early reptiles.[32] The skin, at least in the more advanced forms probably had a water-tight epidermal horny overlay, similar to the one seen in today's reptiles, though they lacked horny claws.[33][34] In chroniosuchians and some seymouriamorphs, like Discosauriscus, dermal scales are found in post-metamorphic specimens, indicating they may have had a "knobbly", if not scaly, appearance.[35] With reptiliomorph anthracosaurs having evolved small near-circular keratinous scales, their amniote descendants further covered almost their entire body with them, and also formed claws of keratin, with both scales and claws making cutaneous respiration and water absorption impossible, making them breathe through their mouths and nostrils, and drink water through mouth.

Seymouriamorphs reproduced in amphibian fashion with aquatic eggs that hatched into larvae (tadpoles) with external gills;[36] it is unknown how other tetrapods traditionally assigned to Reptiliomorpha reproduced.

Evolutionary history

[edit]Early reptiliomorphs

[edit]

During the Carboniferous and Permian periods, some tetrapods started to evolve towards a reptilian condition. Some of these tetrapods (e.g. Archeria, Eogyrinus) were elongate, eel-like aquatic forms with diminutive limbs, while others (e.g. Seymouria, Solenodonsaurus, Diadectes, Limnoscelis) were so reptile-like that until quite recently they actually had been considered to be true reptiles, and it is likely that to a modern observer they would have appeared as large to medium-sized, heavy-set lizards. Several groups however remained aquatic or semiaquatic. Some of the chroniosuchians show the build and presumably habits of modern crocodiles and were probably also similar to crocodylians in that they were river-side predators. While some other Chroniosuchians possessed elongated newt- or eel-like bodies. The two most terrestrially adapted groups were the medium-sized insectivorous or carnivorous Seymouriamorpha and the mainly herbivorous Diadectomorpha, with many large forms. The latter group has, in most analysis, the closest relatives of the Amniotes.[37]

The earliest known fossil evidence of reptiliomorphs are amniote tracks from the early Mississippian (Tournaisian) of Australia. These discoveries suggest that contrary to prior assumptions, reptiliomorphs must have diverged from amphibians almost immediately after the start of the Carboniferous, and potentially even before it (during the Devonian).[1]

From aquatic to terrestrial eggs

[edit]

Their terrestrial life style combined with the need to return to the water to lay eggs hatching to larvae (tadpoles) led to a drive to abandon the larval stage and aquatic eggs. A possible reason may have been competition for breeding ponds, to exploit drier environments with less access to open water, or to avoid predation on tadpoles by fish, a problem still plaguing modern amphibians.[38] Whatever the reason, the drive led to internal fertilization and direct development (completing the tadpole stage within the egg). A striking parallel can be seen in the frog family Leptodactylidae, which has a very diverse reproductive system, including foam nests, non-feeding terrestrial tadpoles and direct development. The Diadectomorphans generally being large animals would have had correspondingly large eggs, unable to survive on land.[39]

Fully terrestrial life was achieved with the development of the amniote egg, where a number of membranous sacks protect the embryo and facilitate gas exchange between the egg and the atmosphere. The first to evolve was probably the allantois, a sack that develops from the gut/yolk-sack. This sack contains the embryo's nitrogenous waste (urea) during development, stopping it from poisoning the embryo. A very small allantois is found in modern amphibians. Later came the amnion surrounding the fetus proper, and the chorion, encompassing the amnion, allantois, and yolk-sack.[citation needed]

Origin of amniotes

[edit]

Exactly where the border between reptile-like amphibians (non-amniote reptiliomorphs) and amniotes lies will probably never be known, as the reproductive structures involved fossilize poorly, but various small, advanced reptiliomorphs have been suggested as the first true amniotes, including Solenodonsaurus, Casineria and Westlothiana. Such small animals laid small eggs, 1 cm in diameter or less. Small eggs would have a small enough volume to surface ratio to be able to develop on land without the amnion and chorion actively affecting gas exchange, setting the stage for the evolution of true amniotic eggs.[39] Although the first true amniotes probably appeared as early as the Middle Mississippian sub-epoch, non-amniote (or amphibian) reptiliomorph lineages coexisted alongside their amniote descendants for many millions of years. By the middle Permian the non-amniote terrestrial forms had died out, but several aquatic non-amniote groups continued to the end of the Permian, and in the case of the chroniosuchians survived the end Permian mass extinction, only to die out prior to the end of the Triassic. Meanwhile, the single most successful daughter-clade of the reptiliomorphs, the amniotes, continued to flourish and evolve into a staggering diversity of tetrapods including mammals, reptiles, and birds.

Gallery

[edit]-

Proterogyrinus, an early embolomere

-

Pteroplax, an aquatic embolomere

-

Silvanerpeton, an indeterminate Carboniferous reptiliomorph

-

Eldeceeon, an indeterminate Carboniferous reptiliomorph

-

Chroniosaurus, a Permian chroniosuchian

-

Madygenerpeton, a Triassic chroniosuchian

-

Kotlassia, an aquatic seymouriamorph

-

Solenodonsaurus, an "advanced" reptiliomorph

-

Casineria, an amniote-like reptiliomorph

-

Tseajaia, a diadectomorph

-

Diasparactus, a diadectid diadectomorph

-

Thylacinus, an amniote synapsid

-

Velociraptor, an amniote sauropsid

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Long, John A.; Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz; Garvey, Jillian; Clement, Alice M.; Camens, Aaron B.; Eury, Craig A.; Eason, John; Ahlberg, Per E. (2025-05-14). "Earliest amniote tracks recalibrate the timeline of tetrapod evolution". Nature: 1–8. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-08884-5. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 12119326.

- ^ Rowe, T. (2004). "Chordate phylogeny and development". Assembling the Tree of Life. J. Cracraft and M. J. Donoghue, eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 384–409. ISBN 0-19-517234-5.

- ^ a b de Queiroz, K.; Cantino, P. D.; Gauthier, J. A., eds. (2020). "Pan-Amniota T. Rowe 2004 [M. Laurin and T. R. Smithson], converted clade name". Phylonyms: A Companion to the PhyloCode. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 789–792. ISBN 978-1-138-33293-5.

- ^ a b "Pan-Amniota". RegNum.

- ^ Laurin, M. (2001). "L'utilisation de la taxonomie phylogénétique en paléontologie: avantages et inconvénients". Biosystema. 19: 197–211.

- ^ a b c d Vallin, Grégoire; Laurin, Michel (2004). "Cranial morphology and affinities of Microbrachis, and a reappraisal of the phylogeny and lifestyle of the first amphibians". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (1): 56–72. doi:10.1671/5.1. S2CID 26700362.

- ^ a b c d Ruta, M.; Coates, M.I.; Quicke, D.L.J. (2003). "Early tetrapod relationships revisited". Biological Reviews. 78 (2): 251–345. doi:10.1017/S1464793102006103. PMID 12803423. S2CID 31298396.

- ^ a b c Benton, M. J. (2000), Vertebrate Paleontology, 2nd Ed. Blackwell Science Ltd 3rd ed. 2004 – see also taxonomic hierarchy of the vertebrates, according to Benton 2004

- ^ Hodnett, John-Paul M.; Lucas, Spencer G. (2018). "A nonmarine Late Pennsylvanian vertebrate assemblage in a marine bromalite from the Manzanita Mountains, Bernalillo County, New Mexico". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 79: 251–260.

- ^ Adams, Gabrielle R. (2020). "3. A phylogenetic analysis of NSM 994GF1.1 to determine the placement of embolomeres in the tetrapod tree". Description of Calligenethlon watsoni based on computed tomography and resulting implications for the phylogenetic placement of embolomeres (MSc thesis). Carleton University.

- ^ Pardo, J. D. (2023). "New information on the neurocranium of Archeria crassidisca and the relationships of the Embolomeri". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlad156.

- ^ a b c Laurin, M.; Reisz, R.R. (1999). "A new study of Solenodonsaurus janenschi, and a reconsideration of amniote origins and stegocephalian evolution". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 36 (8): 1239–1255. doi:10.1139/e99-036.

- ^ Säve-Söderbergh, G. (1934). "Some points of view concerning the evolution of the vertebrates and the classification of this group". Arkiv för Zoologi. 26A: 1–20.

- ^ Säve-Söderbergh, G. (1935). "On the dermal bones of the head in labyrinthodont stegocephalians and primitive Reptilia with special reference to Eotriassic stegocephalians from East Greenland". Meddelelser om Grønland. 98 (3): 1–211.

- ^ Panchen, A. L. (1970). Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie - Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology Part 5a - Batrachosauria (Anthracosauria), Gustav Fischer Verlag - Stuttgart & Portland, 83 pp., ISBN 3-89937-021-X.

- ^ Carroll, R. L., (1988): Vertebrate paleontology and evolution. W. H. Freeman and company, New York.

- ^ Carroll, R. (2002). "Palaeontology: Early land vertebrates". Nature. 418 (6893): 35–36. Bibcode:2002Natur.418...35C. doi:10.1038/418035a. PMID 12097898. S2CID 5522292.

- ^ Hildebrand, M.; Goslow, G. E. Jr (2001). Analysis of vertebrate structure. Principal ill. Viola Hildebrand. New York: Wiley. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-471-29505-1.

- ^ Gauthier, J., Kluge, A.G., & Rowe, T. (1988): "The early evolution of the Amniota". In The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods: Volume 1: Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds. Edited by M.J. Benton. Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 103–155.

- ^ Von Huene, F., (1956), Paläontologie und Phylogenie der niederen Tetrapoden, G. Fischer, Jena.

- ^ Benton, M.J. (2015). "Appendix: Classification of the Vertebrates". Vertebrate Paleontology (4th ed.). Wiley Blackwell. 433–447. ISBN 978-1-118-40684-7.

- ^ Systema Naturae (2000) / Classification Superorder Reptiliomorpha Archived 2006-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Laurin, M.; Reisz, R.R. (1997). "A new perspective on tetrapod phylogeny". In Sumida, S.S.; Martin, K.L.M. (eds.). Amniote Origins: Completing the Transition to Land. Academic Press. pp. 9–60. ISBN 978-0-12-676460-4.

- ^ a b Ruta, M.; Coates, M.I. (2007). "Dates, nodes and character conflict: addressing the lissamphibian origin problem". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (1): 69–122. doi:10.1017/S1477201906002008. S2CID 86479890.

- ^ Hillary C. Maddin, Farish A. Jenkins Jr and Jason S. Anderson (2012). "The braincase of Eocaecilia micropodia (Lissamphibia, Gymnophiona) and the origin of caecilians". PLOS ONE. 7 (12) e50743. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...750743M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050743. PMC 3515621. PMID 23227204.

- ^ Carroll, R. L., (1988): Vertebrate paleontology and evolution. W. H. Freeman and company, New York, p. 167 and 169.

- ^ Palaeos Reptilomorpha Archived April 9, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lombard, R. Eric; Bolt, John R. (1979). "Evolution of the tetrapod ear: An analysis and reinterpretation". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 11: 19–76. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1979.tb00027.x.

- ^ Chapter 4: "The early tetrapods and amphibians." In: Benton, M. J. (2004), Vertebrate Paleontology, 3rd ed. Blackwell Science Ltd.

- ^ Romer, A.S. & T.S. Parsons. 1977. The Vertebrate Body. 5th ed. Saunders, Philadelphia. (6th ed. 1985)

- ^ Palaeos Reptilomorpha: Cotylosauria Archived 2005-07-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Romer, A. S. (1946). "The primitive reptile Limnoscelis restudied". American Journal of Science. 244 (3): 149–88. Bibcode:1946AmJS..244..149R. doi:10.2475/ajs.244.3.149.

- ^ Smithson, T. R.; Paton, R. L.; Clack, J. A. (1999). "An amniote-like skeleton from the Early Carboniferous of Scotland". Nature. 398 (672 7): 508–13. Bibcode:1999Natur.398..508P. doi:10.1038/19071. S2CID 204992355.

- ^ Maddin HC, Eckhart L, Jaeger K, Russell AP, Ghannadan M (April 2009). "The anatomy and development of the claws of Xenopus laevis (Lissamphibia: Anura) reveal alternate pathways of structural evolution in the integument of tetrapods". Journal of Anatomy. 214 (4): 607–19. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01052.x. PMC 2736125. PMID 19422431.

- ^ Laurin, Michel (1996). "A reevaluation of Ariekanerpeton, a Lower Permian seymouriamorph (Vertebrata: Seymouriamorpha) from Tadzhikistan". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 16 (4): 653–65. doi:10.1080/02724634.1996.10011355. JSTOR 4523764.

- ^ Špinar, Z. V. (1952). "Revision of some Morovian Discosauriscidae". Rozpravy Ústředního ústavu Geologického. 15: 1–160. OCLC 715519162.

- ^ Laurin, M. (1996): Phylogeny of Stegocephalians, from the Tree of Life Web Project

- ^ Duellman, W.E. & Trueb, L. (1994): Biology of amphibians. The Johns Hopkins University Press

- ^ a b Carroll R.L. (1991). "The origin of reptiles". In Schultze H.-P.; Trueb L. (eds.). Origins of the higher groups of tetrapods — controversy and consensus. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 331–53.