Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Uncial script

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2013) |

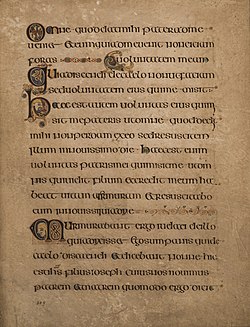

Uncial is a majuscule[1] script (written entirely in capital letters) commonly used from the 4th to 8th centuries AD by Latin and Greek scribes.[2] Uncial letters were used to write Greek and Latin, as well as Gothic, and are the current style for Coptic and Nobiin.

Development

[edit]

Early uncial script most likely developed from late rustic capitals. Early forms are characterized by broad single-stroke letters using simple round forms taking advantage of the new parchment and vellum surfaces, as opposed to the angular, multiple-stroke letters, which are more suited for rougher surfaces, such as papyrus. In the oldest examples of uncial, such as the fragment of De bellis macedonicis in the British Library, of the late 1st–early 2nd centuries,[3][4] all of the letters are disconnected from one another, and word separation is typically not used. Word separation, however, is characteristic of later uncial usage.

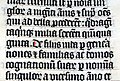

As the script evolved over the centuries, the characters became more complex. Specifically, around AD 600, flourishes and exaggerations of the basic strokes began to appear in more manuscripts. Ascenders and descenders were the first major alterations, followed by twists of the tool in the basic stroke and overlapping. By the time the more compact minuscule scripts arose circa AD 800, some of the evolved uncial styles formed the basis for these simplified, smaller scripts. There are over 500 surviving copies of uncial script; by far the larger number of these predate the Carolingian Renaissance. Uncial was still used, particularly for copies of the Bible, until around the 10th century outside of Ireland. The insular variant of uncial remained the standard script used to write the Irish language until the middle of the 20th century.[5]

Forms

[edit]

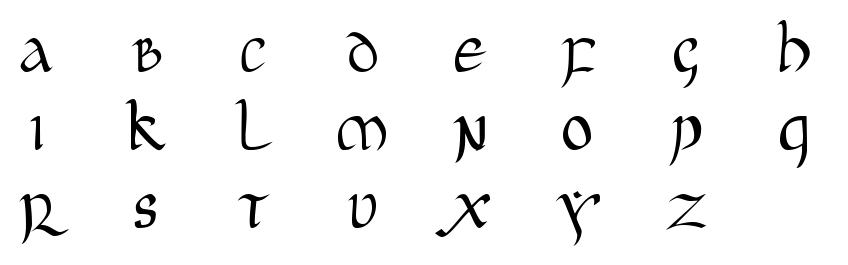

In general, there are some common features of uncial script:

- ⟨f⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨p⟩, ⟨s⟩, ⟨t⟩ are relatively narrow.

- ⟨m⟩, ⟨n⟩ and ⟨u⟩ are relatively broad; ⟨m⟩ is formed with curved strokes (although a straight first stroke may indicate an early script), and ⟨n⟩ is written as ⟨ɴ⟩ to distinguish it from ⟨r⟩ and ⟨s⟩.

- ⟨e⟩ is formed with a curved stroke, and its arm (or hasta) does not connect with the top curve; the height of the arm can also indicate the age of the script (written in a high position, the script is probably early, while an arm written closer to the middle of the curve may indicate a later script).

- ⟨l⟩ has a small base, not extending to the right to connect with the next letter.

- ⟨r⟩ has a long, curved shoulder ⟨ꞃ⟩, often connecting with the next letter.

- ⟨s⟩ resembles (and is the ancestor of) the "long s" ⟨ſ⟩; in uncial it ⟨ꞅ⟩ looks more like ⟨r⟩ than ⟨f⟩.

In later uncial scripts, the letters are sometimes drawn haphazardly; for example, ⟨ll⟩ runs together at the baseline, bows (for example in ⟨b⟩, ⟨p⟩, ⟨r⟩) do not entirely curve in to touch their stems, and the script is generally not written as cleanly as previously.

National styles

[edit]Due to its extremely widespread use, in Byzantine, African, Italian, French, Spanish, and "insular" (Irish, Welsh, and English) centres, there were many slightly different styles in use:

- African (i.e. Roman North African) uncial is more angular than other forms of uncial. In particular, the bow of the letter ⟨a⟩ is particularly sharp and pointed.

- Byzantine uncial has two variants, each with unique features: "b-d uncial" uses forms of ⟨b⟩ and ⟨d⟩ which are closer to half-uncial (see below), and was in use in the 4th and 5th centuries; "b-r" uncial, in use in the 5th and 6th centuries, has a form of ⟨b⟩ that is twice as large as the other letters, and an ⟨r⟩ with a bow resting on the baseline and the stem extending below the baseline.

- Italian uncial has flatter tops on the round letters (⟨c⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨o⟩ etc.), and a sharp bow (as in African uncial), an almost horizontal rather than vertical stem in ⟨d⟩, and forked finials (i.e., serifs in some letters such as ⟨f⟩, ⟨l⟩, ⟨t⟩ and ⟨s⟩).

- Insular uncial (not to be confused with the separate Insular script) generally has definite word separation, and accent marks over stressed syllables, probably because Irish scribes did not speak a language descended from Latin. They also use specifically Insular scribal abbreviations not found in other uncial forms, use wedge-shaped finials, connect a slightly subscript "pendant ⟨i⟩" with ⟨m⟩ or ⟨h⟩ (when at the end of a word), and decorate the script with animals and dots ("Insular dotting", often in groups of three).

- French (that is, Merovingian) uncial uses thin descenders (in ⟨g⟩, ⟨p⟩ etc.), an ⟨x⟩ with lines that cross higher than the middle, and a ⟨d⟩ with a curled stem (somewhat resembling an apple), and there are many decorations of fish, trees, and birds.

- Cyrillic manuscript developed from Greek uncial in the late ninth century (mostly replacing the Glagolitic alphabet), and was originally used to write the Old Church Slavonic liturgical language. The earlier form was called ustav (predominant in the 11–14th centuries), and later developed into semi-ustav script (or poluustav, 15–16th centuries).

Etymology

[edit]

There is some doubt about the original meaning of the word. Uncial itself probably comes from St. Jerome's preface to the Book of Job, where it is found in the form uncialibus, but it is possible that this is a misreading of inicialibus (though this makes little sense in the context), and Jerome may have been referring to the larger initial letters found at the beginning of paragraphs.[6]

- Habeant qui volunt veteres libros, vel in membranis purpureis auro argentoque descriptos, vel uncialibus ut vulgo aiunt litteris onera magis exarata quam codices.

- "Let those who so desire have old books, or books written in gold and silver on purple parchment, or burdens {rather than books} written in uncial letters, as they are popularly called."

In classical Latin uncialis could mean both "inch-high" and "weighing an ounce", and it is possible that Jerome was punning on this; he may conceivably also have been playing with the other meaning of codex, "block of wood".[6]

The term uncial in the sense of describing this script was first used by Jean Mabillon in the early 18th century. Thereafter his definition was refined by Scipione Maffei, who used it to refer to this script as distinct from Roman square capitals.

Other uses

[edit]

The word, uncial, is also sometimes used to refer to manuscripts that have been scribed in uncial, especially when differentiating from those penned with minuscule. Some of the most noteworthy Greek uncials are:

- Codex Sinaiticus

- Codex Vaticanus

- Codex Alexandrinus

- – these being three of what are often called the four great uncial codices

- Codex Bezae

- Codex Petropolitanus Purpureus

The Petropolitanus is considered by some to contain optimum uncial style. It is also an example of how large the characters were getting.

For further details on these manuscripts, see Guglielmo Cavallo Ricerche sulla Maiuscola Biblica (Florence, 1967).

Modern calligraphy usually teaches a form of evolved Latin-based uncial hand that would probably be best compared to the later 7th to 10th century examples, though admittedly, the variations in Latin uncial are much wider and less rigid than Greek. Modern uncial has borrowed heavily from some of the conventions found in more cursive scripts, using flourishes, variable width strokes, and on occasion, even center axis tilt.

In a way comparable to the continued widespread use of the blackletter typefaces for written German until well into the 20th century, Gaelic letterforms, which are similar to uncial letterforms, were conventionally used for typography in Irish until the 1950s. The script is still widely used in this way for titles of documents, inscriptions on monuments, and other 'official' uses. Strictly speaking, the Gaelic script is insular, not uncial. Uncial Greek (commonly called "Byzantine lettering" by Greeks themselves) is commonly used by the Greek Orthodox Church and various institutions and individuals in Greece to this day. The Modern Greek state has also used uncial script on several occasions in official capacity (such as on seals or government documents etc.) as did many of the Greek provisional governments during the Greek War of Independence. The height of uncial usage by the Modern Greek State was during the Greek military junta of 1967–1974, with even modern drachma coins had uncial lettering on them. Since the Metapolitefsi, the Greek State has stopped using uncial script.

Half-uncial

[edit]

The term half-uncial or semi-uncial was first deployed by Scipione Maffei, Istoria diplomatica (Mantua, 1727);[7] he used it to distinguish what seemed like a cut-down version of uncial in the famous Codex Basilicanus of Hilary, which contains sections in each of the two types of script. The terminology was continued in the mid-18th century by René-Prosper Tassin and Charles-François Toustain.

Despite the common and well-fixed usage, half-uncial is a poor name to the extent that it suggests some organic debt to regular uncial, though both types share features inherited from their ancient source, capitalis rustica.[8] According to other views, it is derived from the late Roman cursive.[9]

It was first used around the 3rd century (if its earliest example isn't considered a transitional variant of the rustic script, as Leonard Boyle did) and remained in use until the end of the 8th century. The early forms of half-uncial were used for pagan authors and Roman legal writing, while in the 6th century the script came to be used in Africa and Europe (but not as often in insular centres) to transcribe Christian texts.

Half-uncial forms

[edit]Some general forms of half-uncial letters are:

- ⟨a⟩ is usually round ⟨ɑ⟩, sometimes with a slightly open top

- ⟨b⟩ and ⟨d⟩ have vertical stems, identical to the modern letters

- ⟨g⟩ has a flat top, no bow, and a curved descender ⟨ᵹ⟩ (somewhat resembling the digit 5)

- ⟨t⟩ has a curved shaft ⟨ꞇ⟩

- ⟨n⟩, ⟨r⟩, and ⟨s⟩ are similar to their uncial counterparts (with the same differences compared to modern letters)

Half-uncial was brought to Ireland in the 5th century, and from there to England in the 7th century. In England, it was used to create the Old English Latin alphabet in the 8th century.

Letters

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Glaister, Geoffrey Ashall (1996). Encyclopedia of the Book (2nd ed.). New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press. p. 494. ISBN 1-884718-14-0. LCCN 96007274. OCLC 48110905. OL 21630251M. Retrieved 2025-03-27.

- ^ Crystal, David (1995). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. University of Cambridge Press. p. 258. ISBN 0-521-40179-8. OCLC 185322552. Retrieved 2025-03-27.

- ^ "Papyrus 745". Digitised Manuscripts. British Library. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ^ O'Hogan, Cillian (2015-06-12). "The Beginnings of the Codex". Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts Blog. British Library. Archived from the original on 2025-01-23. Retrieved 2025-03-27.

- ^ Miller, Robert M. (2005). New Hart's Rules: The Handbook of Style for Writers and Editors. Oxford, United Kingdom: OUP Oxford. p. 208. ISBN 9780198610410. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ a b "uncial, adj. & n. meanings, etymology and more | Oxford English Dictionary". www.oed.com. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Maffei, Scipione (1727). Istoria diplomatica che serve d'introduzione all'arte critica in tal materia (in Italian). Mantova: A. Tumermani.

- ^ L. E. Boyle, "'Basilicanus' of Hilary Revisited," in Integral Palaeography, with an introduction by F. Troncarelli (Turnhout, 2001), 105–17.

- ^ Bischoff, Bernhard (1990). Latin Palaeography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Translated by Ó Cróinín, transl. by Dáibhí; Ganz, David. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. P. 76.

External links

[edit]- More information at Earlier Latin Manuscripts

- 'Fonts for Latin Paleography: User's Manual. 6th edition' A manual of Latin paleography; a comprehensive PDF file containing 82 pages profusely illustrated, 4 January 2024).