Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Scientific Linux

View on Wikipedia

| Scientific Linux | |

|---|---|

| |

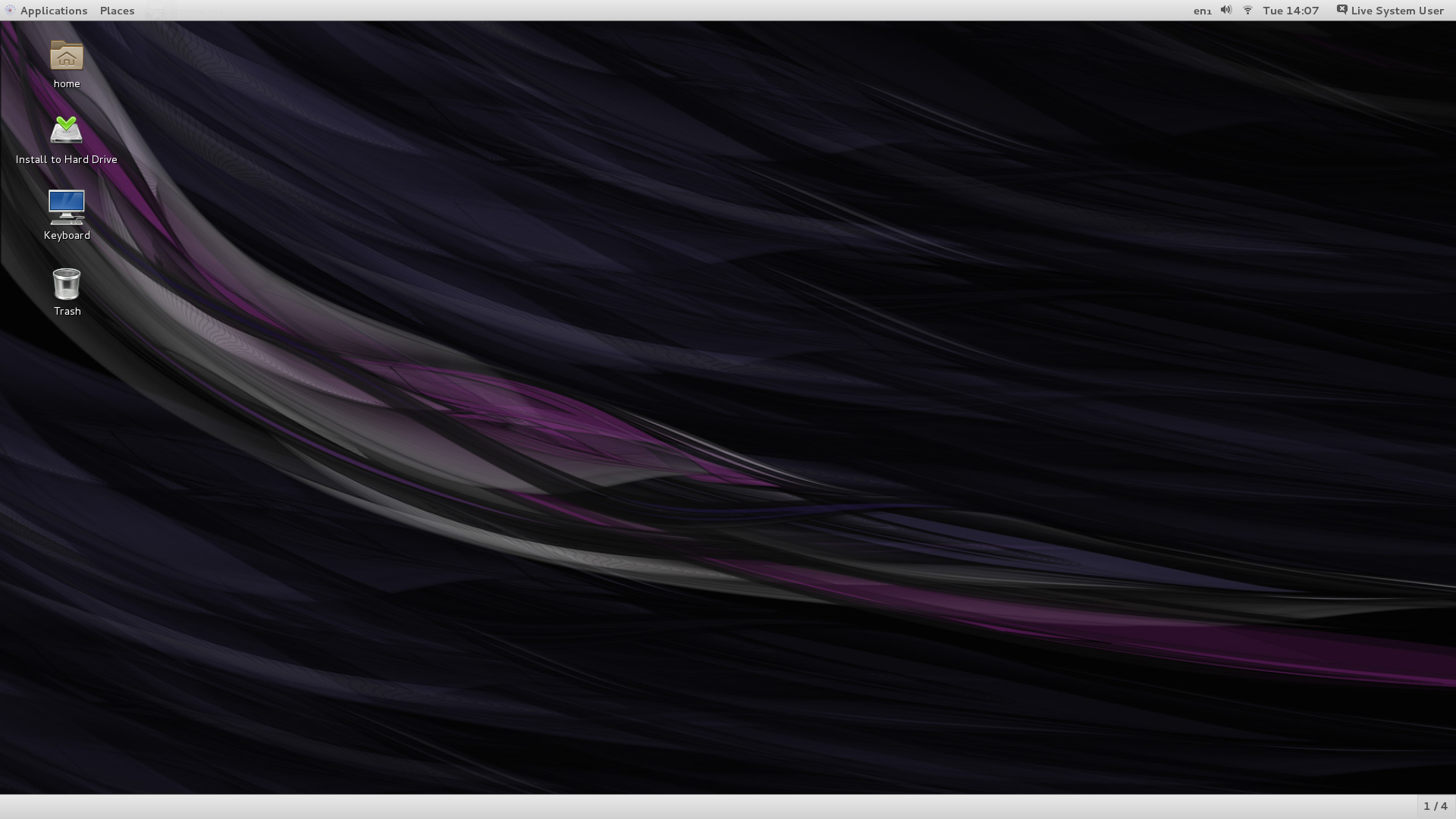

Scientific Linux 7.0 with GNOME | |

| Developer | Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) / European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) |

| OS family | Linux (Unix-like) |

| Working state | Discontinued |

| Source model | Open source |

| Initial release | May 10, 2004 |

| Final release | 7.9[1] / 20 October 2020 |

| Marketing target | Scientific purpose / High Performance Computing / Servers / Desktops[2] |

| Update method | Yum (PackageKit) |

| Package manager | RPM Package Manager |

| Supported platforms | x86, x86-64 |

| Kernel type | Monolithic (Linux) |

| Default user interface | GNOME |

| License | GNU GPL & Various others. |

| Official website | www |

Scientific Linux (SL) is a discontinued Linux distribution produced by Fermilab, CERN, DESY and by ETH Zurich. It is a free and open-source operating system based on Red Hat Enterprise Linux.[3]

This product is derived from the free and open-source software made available by Red Hat, but is not produced, maintained or supported by them.

In April 2019, it was announced that feature development for Scientific Linux would be discontinued, but that maintenance will continue to be provided for the 6.x and 7.x releases through the end of their life cycles. Fermilab and CERN will utilize CentOS Stream[4] and AlmaLinux[5][6][7] for their deployment of 8.x release instead.

History

[edit]Fermilab already had a Linux distribution known as Fermi Linux, a long-term support release based on Red Hat Enterprise Linux. CERN was creating their next version of CERN Linux, also based on RHEL. CERN contacted Fermilab about doing a collaborative release. Connie Sieh was the main developer and driver behind the first prototypes and initial release.[2] The first official release of Scientific Linux was version 3.0.1, released on May 10, 2004.

In 2012 Scientific Linux was maintained by a cooperative of science labs and universities. Fermilab was its primary sponsor.[2]

In 2015, CERN began migrating away from Scientific Linux to CentOS.[8][9]

Design philosophy

[edit]The primary purpose of Scientific Linux is to produce a common Linux distribution for various labs and universities around the world, thus reducing duplicated effort. The main goals are to have everything compatible with Red Hat Enterprise Linux with only minor additions and changes, and to allow easy customization for a site, without disturbing the Linux base.[10] Unlike other distributions such as Poseidon Linux, it does not contain a large collection of scientific software as its name may suggest.[3][11] However, it provides good compatibility to install such software.

Features

[edit]Scientific Linux is derived from Red Hat Enterprise Linux without protected components such as Red Hat trademarks, thus making it freely available.[12] New releases are typically produced about two months after each Red Hat release.[2] As well as a full distribution equal to two DVDs, Scientific Linux is also available in LiveCD and LiveDVD versions.[12]

Scientific Linux offers wireless and Bluetooth out of the box, and it comes with a comprehensive range of software, such as multimedia codecs, Samba, and Compiz,[11] as well as servers and clients, storage clients, networking, and system administration tools.[2]

It also contains a set of tools for making custom versions, thus allowing institutions and individuals to create their own variant.[2]

Release history

[edit]Historical releases of Scientific Linux are the following.[13][14] Each release is subjected to a period of public testing before it is considered 'released'.

| Scientific Linux release | Codename | Architectures | RHEL base | Scientific Linux release date | Red Hat Enterprise Linux release date | Delay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0.1 | Lithium | i386, x86-64 | 3.1 | 2004-05-10 | 2004-01-16 | 106d |

| 4[2] | Beryllium | 4 | 2005-04-20 | 2005-02-14 | 65d | |

| 5[15][16] | Boron | 5 | 2007-05-14 | 2007-03-14 | 61d | |

| 6[17][18][19][20] | Carbon | 6 | 2011-03-03 | 2010-11-10 | 113d | |

| 7[21][22] | Nitrogen | x86-64 | 7 | 2014-10-13 | 2014-06-10 | 125d |

Support

[edit]Security updates are provided for as long as Red Hat continues to release updates and patches for their versions.[23]

| Scientific Linux release | Full updates | Maintenance updates |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2006-07-20 | 2010-10-31 |

| 4 | 2009-03-31 | 2012-02-29 |

| 5 | Q1 2014 | 2017-03-31 |

| 6 | Q2 2017 | 2020-11-30 |

| 7 | Q4 2019 | 2024-06-30 |

See also

[edit]- Fermi Linux, Fermilab's own custom version of Scientific Linux

- CentOS, another distribution based on Red Hat Enterprise Linux

- AlmaLinux, the recommended replacement distribution

- Rocks Cluster Distribution, a Linux distribution intended for high-performance computing clusters

References

[edit]- ^ "Scientific Linux 7.9 x86_64 is now available". October 20, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carla Schroder (March 23, 2012). "Scientific Linux, the Great Distro With the Wrong Name". Linux.com.

- ^ a b "General Questions about Scientific Linux (Community)". Scientific Linux.

- ^ Cooper, Glenn (October 25, 2021). "Fermilab/CERN recommendation for Linux distribution". listserv.fnal.gov. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Fermilab/CERN recommendation for Linux distribution". news.fnal.gov. December 7, 2022. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ "Fermilab/CERN recommendation for Linux distribution". December 7, 2022.

- ^ "Which distribution should I use?". Retrieved June 6, 2025.

- ^ "Scientific Linux @ CERN: Next Version". CERN. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "CC7: CERN CentOS 7". CERN. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Welcome to Scientific Linux (SL)". Scientifix Linux.

- ^ a b "Scientific Linux – It blinded me with science!". Dedoimedo. February 3, 2010.

- ^ a b "Scientific Linux 5.6 Live released". The H. July 11, 2011. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013.

- ^ "News Archives". Scientifix Linux. Archived from the original on March 3, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

- ^ "S.L. Distribution Roadmap". Scientifix Linux. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ Scientific Linux – It blinded me with science!, Dedoimedo

- ^ DistroWatch Weekly, Issue 351, 26 April 2010

- ^ Scientific Linux 6 – Another great distro, but, Dedoimedo

- ^ DistroWatch Weekly, Issue 419, 22 August 2011

- ^ Scientific Linux 6.1 Carbon review – Almost there, Dedoimedo

- ^ Scientific Linux 6.5 Carbon – Fast and dubious, Dedoimedo

- ^ Scientific Linux 7.1 review – More fiasco, Dedoimedo

- ^ Download Scientific Linux 7.5, Softpedia Linux

- ^ "End of life dates for SL versions". Scientifix Linux. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

External links

[edit]Scientific Linux

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Development

Historical Background

Scientific Linux originated as a collaborative effort to address the specific computing needs of high-energy physics research communities. The project was initiated in 2003 at the HEPiX conference by Fermilab, with CERN joining shortly thereafter to sponsor builds for additional architectures like Itanium. On May 10, 2004, Fermilab and CERN announced the initial release of Scientific Linux, a custom rebuild of Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) 3.1, aimed at providing a stable, binary-compatible platform for scientific workloads without proprietary restrictions. This distribution was developed to unify disparate Linux environments across laboratories, enabling seamless collaboration on computationally intensive tasks such as particle physics simulations.[6] The project quickly expanded in the mid-2000s, incorporating contributions from additional institutions to broaden its applicability and maintenance base. By 2005–2006, DESY (Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron) and ETH Zurich joined the effort, providing expertise in areas like package customization and hardware support, which solidified Scientific Linux as a multi-institutional collaboration focused on long-term stability for global scientific computing. This growth ensured the distribution's adaptability to diverse research environments while maintaining compatibility with upstream RHEL updates.[3] In 2015, CERN began migrating away from Scientific Linux toward CentOS, influenced by Red Hat's evolving policies on source code distribution and the acquisition of CentOS in 2014, which aligned more closely with CERN's operational needs for upstream integration. Fermilab continued as the primary maintainer, sustaining development and security updates for existing versions to support ongoing high-energy physics experiments. However, on April 22, 2019, Fermilab announced the cessation of new feature development for Scientific Linux, shifting focus to maintenance only while recommending collaboration with the CentOS community for future enhancements.[7][8] Maintenance efforts persisted until the official end-of-life for Scientific Linux 7 was declared on June 30, 2024, after which no further updates would be issued, marking the full discontinuation of the distribution. In response to this EOL, Fermilab and CERN recommended transitioning to alternatives such as CentOS Stream for development previews or AlmaLinux for stable, RHEL-compatible environments, with a joint endorsement of AlmaLinux as the standard for experiments announced in December 2022. This shift reflects the broader evolution of open-source Linux ecosystems tailored to scientific computing demands.[9]Sponsoring Organizations and Collaborations

Scientific Linux was primarily sponsored by Fermilab, the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory operated by the U.S. Department of Energy, and CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, with the project initiated in 2003 to provide a reliable platform for particle physics simulations and large-scale data analysis in high-energy physics experiments.[2][10] These organizations recognized the need for a consistent operating system across international collaborations, such as those involving the Large Hadron Collider at CERN and accelerator experiments at Fermilab.[11] Additional contributions came from DESY, the Deutsches Elektronensynchrotron in Germany, which supported adaptations for accelerator physics research, and ETH Zurich, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, focusing on enhancements for broader computational science applications in scientific workflows.[3] This involvement extended the distribution's utility beyond particle physics to other domains requiring high-performance computing stability.[12] The collaborative model centered on an open-source rebuild of Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL), leveraging the publicly available RHEL source code under the GNU General Public License (GPL) to create a freely distributable variant without proprietary elements.[1] Development relied on shared code repositories hosted by Fermilab and CERN, along with public mailing lists for coordinating bug reports, feature requests, and synchronized updates to maintain compatibility across user sites.[13] This approach fostered a decentralized yet cohesive effort among global contributors. The core motivations for these organizations were to deliver a cost-free, enterprise-grade alternative to commercial RHEL, eliminating licensing expenses for resource-intensive scientific deployments while prioritizing long-term stability and reproducibility essential for validating experimental results in physics research.[2][11] By rebuilding from official sources, the project ensured binary compatibility with RHEL ecosystems used in laboratories worldwide, supporting reproducible computations without vendor lock-in. Over time, the collaborations evolved; in 2015, CERN began transitioning from Scientific Linux to CentOS 7 as its primary distribution due to internal policy changes favoring broader community-supported options, while continuing limited support for existing Scientific Linux installations.[14] Fermilab assumed primary maintenance responsibilities thereafter, guiding the project until announcing its wind-down in 2019 to align with shifting priorities in high-energy physics computing infrastructure.[15]Design and Philosophy

Core Principles

Scientific Linux was fundamentally designed around the principle of binary compatibility with its upstream distribution, Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL), ensuring that applications compiled for one could execute seamlessly on the other without requiring recompilation.[1][11] This approach allowed Scientific Linux to inherit RHEL's robust ecosystem while providing a free alternative tailored for scientific environments, minimizing disruptions in software deployment across high-energy physics laboratories.[2] Adhering to minimalism, the project made only essential modifications to the RHEL base, focusing on enhancements that improved usability for scientific workflows without compromising core stability. For instance, it incorporated support for wireless networking and multimedia codecs, which were often excluded from RHEL due to enterprise licensing constraints, thereby enabling broader hardware compatibility and data handling in research settings. These changes were limited to preserve the integrity of the upstream codebase, with all alterations publicly documented to facilitate transparency and potential upstream integration.[16] Stability took precedence over introducing novel features, with Scientific Linux aligning its release and support cycles directly to RHEL's long-term phases—typically spanning a decade—to safeguard computational reproducibility in long-running scientific simulations and experiments.[2][11] This philosophy avoided frequent updates that might introduce regressions, prioritizing a predictable environment where researchers could rely on consistent system behavior over years of data analysis. Embodying an open-source ethos, Scientific Linux was freely redistributable under the GNU General Public License (GPL) for its kernel and key components, encouraging community contributions while all project modifications were shared publicly and, where feasible, fed back to upstream projects.[1] However, it did not position itself as a comprehensive repository for software; instead, it served as a reliable foundational operating system upon which users could install specialized tools, such as ROOT for data analysis or GEANT4 for particle simulation, without pre-bundled domain-specific applications that might bloat the base system.[2][11]Compatibility and Customization Approach

Scientific Linux maintained high interoperability with Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) through a rebuild process that utilized RHEL's publicly available source RPMs (SRPMs) to generate binary packages, ensuring functional equivalence while adhering to open-source licensing requirements.[1][17] This approach involved compiling the SRPMs in a controlled build environment, applying minimal modifications primarily to remove branding elements or resolve specific compatibility issues, such as integrating open-source alternatives for certain proprietary components where necessary to preserve GPL compliance.[16] The resulting binaries were designed to be bit-for-bit identical to RHEL where possible, minimizing divergence and facilitating seamless use of RHEL documentation, drivers, and applications in scientific workflows.[5] Customization in Scientific Linux emphasized stability and user flexibility without compromising core RHEL parity, achieved via provided scripts and repository configurations that allowed tailored installations. For instance, the distribution included yum configuration scripts (accessible viayum search yum-conf) to enable third-party repositories, enabling users to add scientific libraries like those for high-performance computing or data analysis while maintaining the base system's integrity.[18] These tools supported modular extensions, such as integrating EPEL or other community repositories, ensuring that adaptations did not introduce instability to the underlying RHEL-compatible foundation.[18]

Each Scientific Linux release strictly mirrored a corresponding RHEL point release—for example, Scientific Linux 7 (SL7) aligned with RHEL 7—allowing shared access to errata, security patches, and updates through dedicated SL channels that propagated RHEL fixes with minimal delay.[5] This alignment extended to handling upstream changes, where the project relied on community-maintained mirrors of RHEL sources to ensure continued GPL-compliant access, particularly in response to evolving distribution policies from Red Hat.[17][16]

To support deployment in research-oriented environments like computational clusters, Scientific Linux offered user-centric adaptations including LiveCD and LiveDVD builds, which provided a bootable environment for system recovery, testing, or diskless booting over NFS without requiring a full installation.[19] These rescue modes facilitated rapid troubleshooting and configuration in lab settings, such as mounting images for cluster nodes, enhancing accessibility for scientific users while preserving RHEL compatibility.[20]