Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Agonist

View on Wikipedia

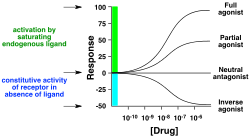

An agonist is a chemical that activates a receptor to produce a biological response. Receptors are cellular proteins whose activation causes the cell to modify what it is currently doing. In contrast, an antagonist blocks the action of the agonist, while an inverse agonist causes an action opposite to that of the agonist.

Etymology

[edit]The word originates from the Greek word ἀγωνιστής (agōnistēs), "contestant; champion; rival" < ἀγών (agōn), "contest, combat; exertion, struggle" < ἄγω (agō), "I lead, lead towards, conduct; drive."

Types of agonists

[edit]Receptors can be activated by either endogenous agonists (such as hormones and neurotransmitters) or exogenous agonists (such as drugs), resulting in a biological response. A physiological agonist is a substance that creates the same bodily responses but does not bind to the same receptor.

- An endogenous agonist for a particular receptor is a compound naturally produced by the body that binds to and activates that receptor. For example, the endogenous agonist for serotonin receptors is serotonin, and the endogenous agonist for dopamine receptors is dopamine.[1]

- Full agonists bind to and activate a receptor with the maximum response that an agonist can elicit at the receptor. One example of a drug that can act as a full agonist is isoproterenol, which mimics the action of adrenaline at β adrenoreceptors. Another example is morphine, which mimics the actions of endorphins at μ-opioid receptors throughout the central nervous system. However, a drug can act as a full agonist in some tissues and as a partial agonist in other tissues, depending upon the relative numbers of receptors and differences in receptor coupling.[medical citation needed]

- A co-agonist works with other co-agonists to produce the desired effect together. NMDA receptor activation requires the binding of both glutamate, glycine and D-serine co-agonists. Calcium can also act as a co-agonist at the IP3 receptor.

- A selective agonist is selective for a specific type of receptor. E.g. buspirone is a selective agonist for serotonin 5-HT1A.

- Partial agonists (such as buspirone, aripiprazole, buprenorphine, or norclozapine) also bind and activate a given receptor, but have only partial efficacy at the receptor relative to a full agonist, even at maximal receptor occupancy. Agents like buprenorphine are used to treat opiate dependence for this reason, as they produce milder effects on the opioid receptor with lower dependence and abuse potential.

- An inverse agonist is an agent that binds to the same receptor binding-site as an agonist for that receptor and inhibits the constitutive activity of the receptor. Inverse agonists exert the opposite pharmacological effect of a receptor agonist, not merely an absence of the agonist effect as seen with an antagonist. An example is the cannabinoid inverse agonist rimonabant.

- A superagonist is a term used by some to identify a compound that is capable of producing a greater response than the endogenous agonist for the target receptor. It might be argued that the endogenous agonist is simply a partial agonist in that tissue.

- An irreversible agonist is a type of agonist that binds permanently to a receptor through the formation of covalent bonds.[2][3]

- A biased agonist is an agent that binds to a receptor without affecting the same signal transduction pathway. Oliceridine is a μ-opioid receptor agonist that has been described to be functionally selective towards G protein and away from β-arrestin2 pathways.[4]

New findings that broaden the conventional definition of pharmacology demonstrate that ligands can concurrently behave as agonist and antagonists at the same receptor, depending on effector pathways or tissue type. Terms that describe this phenomenon are "functional selectivity", "protean agonism",[5][6][7] or selective receptor modulators.[8]

Mechanism of action

[edit]As mentioned above, agonists have the potential to bind in different locations and in different ways depending on the type of agonist and the type of receptor.[9] The process of binding is unique to the receptor-agonist relationship, but binding induces a conformational change and activates the receptor.[9][10] This conformational change is often the result of small changes in charge or changes in protein folding when the agonist is bound.[10][11] Two examples that demonstrate this process are the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor and NMDA receptor and their respective agonists.

For the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, which is a G protein-coupled receptor[10](GPCR), the endogenous agonist is acetylcholine. The binding of this neurotransmitter causes the conformational changes that propagate a signal into the cell.[10] The conformational changes are the primary effect of the agonist, and are related to the agonist's binding affinity and agonist efficacy.[9][12] Other agonists that bind to this receptor will fall under one of the different categories of agonist mentioned above based on their specific binding affinity and efficacy.

The NMDA receptor is an example of an alternate mechanism of action, as the NMDA receptor requires co-agonists for activation. Rather than simply requiring a single specific agonist, the NMDA receptor requires both the endogenous agonists, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and glycine.[11] These co-agonists are both required to induce the conformational change needed for the NMDA receptor to allow flow through the ion channel, in this case calcium.[11] An aspect demonstrated by the NMDA receptor is that the mechanism or response of agonists can be blocked by a variety of chemical and biological factors.[11] NMDA receptors specifically are blocked by a magnesium ion unless the cell is also experiencing depolarization.[11]

These differences show that agonists have unique mechanisms of action depending on the receptor activated and the response needed.[9][10] The goal and process remains generally consistent however, with the primary mechanism of action requiring the binding of the agonist and the subsequent changes in conformation to cause the desired response at the receptor.[9][12] This response as discussed above can vary from allowing flow of ions to activating a GPCR and transmitting a signal into the cell.[9][10]

Activity

[edit]

Potency

[edit]Potency is the amount of agonist needed to elicit a desired response. The potency of an agonist is inversely related to its half maximal effective concentration (EC50) value. The EC50 can be measured for a given agonist by determining the concentration of agonist needed to elicit half of the maximum biological response of the agonist. The EC50 value is useful for comparing the potency of drugs with similar efficacies producing physiologically similar effects. The smaller the EC50 value, the greater the potency of the agonist, the lower the concentration of drug that is required to elicit the maximum biological response.

Therapeutic index

[edit]Therapeutic index is a meaure of a drug's safety margin. When a drug is used therapeutically, it is important to understand the margin of safety that exists between the dose needed for the desired effect and the dose that produces unwanted and possibly dangerous side-effects (measured by the TD50, the dose that produces toxicity in 50% of individuals). This relationship, termed the therapeutic index, is defined as the ratio TD50:ED50. In general, the narrower this margin, the more likely it is that the drug will produce unwanted effects. The therapeutic index emphasizes the importance of the margin of safety, as distinct from the potency, in determining the usefulness of a drug.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Goodman and Gilman's Manual of Pharmacology and Therapeutics. (11th edition, 2008). p14. ISBN 0-07-144343-6

- ^ De Mey JG, Compeer MG, Meens MJ (2009). "Endothelin-1, an Endogenous Irreversible Agonist in Search of an Allosteric Inhibitor". Mol Cell Pharmacol. 1 (5): 246–257.

- ^ Rosenbaum DM, Zhang C, Lyons JA, Holl R, Aragao D, Arlow DH, et al. (January 2011). "Structure and function of an irreversible agonist-β(2) adrenoceptor complex". Nature. 469 (7329): 236–240. Bibcode:2011Natur.469..236R. doi:10.1038/nature09665. PMC 3074335. PMID 21228876.

- ^ DeWire SM, Yamashita DS, Rominger DH, Liu G, Cowan CL, Graczyk TM, et al. (March 2013). "A G protein-biased ligand at the μ-opioid receptor is potently analgesic with reduced gastrointestinal and respiratory dysfunction compared with morphine". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 344 (3): 708–717. doi:10.1124/jpet.112.201616. PMID 23300227. S2CID 8785003.

- ^ Kenakin T (March 2001). "Inverse, protean, and ligand-selective agonism: matters of receptor conformation". FASEB Journal. 15 (3): 598–611. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.334.8525. doi:10.1096/fj.00-0438rev. PMID 11259378. S2CID 18260817.

- ^ Urban JD, Clarke WP, von Zastrow M, Nichols DE, Kobilka B, Weinstein H, et al. (January 2007). "Functional selectivity and classical concepts of quantitative pharmacology". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 320 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.104463. PMID 16803859. S2CID 447937.

- ^ De Min A, Matera C, Bock A, Holze J, Kloeckner J, Muth M, et al. (April 2017). "A New Molecular Mechanism To Engineer Protean Agonism at a G Protein-Coupled Receptor". Molecular Pharmacology. 91 (4): 348–356. doi:10.1124/mol.116.107276. PMID 28167741.

- ^ Smith CL, O'Malley BW (February 2004). "Coregulator function: a key to understanding tissue specificity of selective receptor modulators". Endocrine Reviews. 25 (1): 45–71. doi:10.1210/er.2003-0023. PMID 14769827.

- ^ a b c d e f Colquhoun D (January 2006). "Agonist-activated ion channels". British Journal of Pharmacology. 147 (S1): S17 – S26. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706502. PMC 1760748. PMID 16402101.

- ^ a b c d e f Kruse AC, Ring AM, Manglik A, Hu J, Hu K, Eitel K, et al. (December 2013). "Activation and allosteric modulation of a muscarinic acetylcholine receptor". Nature. 504 (7478): 101–106. Bibcode:2013Natur.504..101K. doi:10.1038/nature12735. PMC 4020789. PMID 24256733.

- ^ a b c d e Zhu S, Stein RA, Yoshioka C, Lee CH, Goehring A, Mchaourab HS, Gouaux E (April 2016). "Mechanism of NMDA Receptor Inhibition and Activation". Cell. 165 (3): 704–714. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.028. PMC 4914038. PMID 27062927.

- ^ a b Strange PG (April 2008). "Agonist binding, agonist affinity and agonist efficacy at G protein-coupled receptors". British Journal of Pharmacology. 153 (7): 1353–1363. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707672. PMC 2437915. PMID 18223670.