Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Histamine

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2-(1H-Imidazol-4-yl)ethanamine

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.092 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Histamine |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H9N3 | |

| Molar mass | 111.148 g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 83.5 °C (182.3 °F; 356.6 K) |

| Boiling point | 209.5 °C (409.1 °F; 482.6 K) |

| Easily soluble in cold water, hot water[1] | |

| Solubility in other solvents | Easily soluble in methanol. Very slightly soluble in diethyl ether.[1] Easily soluble in ethanol. |

| log P | −0.7[2] |

| Acidity (pKa) | Imidazole: 6.04 Terminal NH2: 9.75[2] |

| Pharmacology | |

| L03AX14 (WHO) V04CG03 (WHO) (phosphate) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

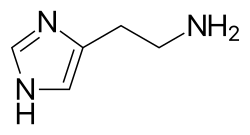

Histamine is an organic nitrogenous compound involved in local immune responses communication, as well as regulating physiological functions in the gut and acting as a neurotransmitter for the brain, spinal cord, and uterus.[3][4] Discovered in 1910, histamine has been considered a local hormone (autocoid) because it is produced without involvement of the classic endocrine glands; however, in recent years, histamine has been recognized as a central neurotransmitter.[5] Histamine is involved in the inflammatory response and has a central role as a mediator of itching.[6] As part of an immune response to foreign pathogens, histamine is produced by basophils and by mast cells found in nearby connective tissues. Histamine increases the permeability of the capillaries to white blood cells and some proteins, to allow them to engage pathogens in the infected tissues.[7] It consists of an imidazole ring attached to an ethylamine chain; under physiological conditions, the amino group of the side-chain is protonated.

Properties

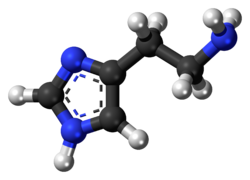

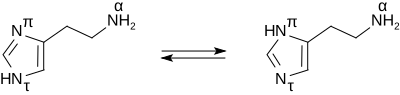

[edit]Histamine base, obtained as a mineral oil mull, melts at 83–84 °C.[8] Hydrochloride[9] and phosphorus[10] salts form white hygroscopic crystals and are easily dissolved in water or ethanol, but not in ether. In aqueous solution, the imidazole ring of histamine exists in two tautomeric forms, identified by which of the two nitrogen atoms is protonated. The nitrogen farther away from the side chain is the 'tele' nitrogen and is denoted by a lowercase tau sign and the nitrogen closer to the side chain is the 'pros' nitrogen and is denoted by the pi sign. The tele tautomer, Nτ-H-histamine, is preferred in solution as compared to the pros tautomer, Nπ-H-histamine.

Histamine has two basic centres, namely the aliphatic amino group and whichever nitrogen atom of the imidazole ring does not already have a proton. Under physiological conditions, the aliphatic amino group (having a pKa around 9.4) will be protonated, whereas the second nitrogen of the imidazole ring (pKa ≈ 5.8) will not be protonated.[11] Thus, histamine is normally protonated to a singly charged cation. Since human blood is slightly basic (with a normal pH range of 7.35 to 7.45) therefore the predominant form of histamine present in human blood is monoprotic at the aliphatic nitrogen. Histamine is a monoamine neurotransmitter.

Synthesis and metabolism

[edit]Histamine is derived from the decarboxylation of the amino acid histidine, a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme L-histidine decarboxylase. It is a hydrophilic vasoactive amine.

Once formed, histamine is either stored or rapidly inactivated by its primary degradative enzymes, histamine-N-methyltransferase or diamine oxidase. In the central nervous system, histamine released into the synapses is primarily broken down by histamine-N-methyltransferase, while in other tissues both enzymes may play a role. Several other enzymes, including MAO-B and ALDH2, further process the immediate metabolites of histamine for excretion or recycling.

Bacteria also are capable of producing histamine using histidine decarboxylase enzymes unrelated to those found in animals. A non-infectious form of foodborne disease, scombroid poisoning, is due to histamine production by bacteria in spoiled food, particularly fish. Fermented foods and beverages naturally contain small quantities of histamine due to a similar conversion performed by fermenting bacteria or yeasts. Sake contains histamine in the 20–40 mg/L range; wines contain it in the 2–10 mg/L range.[12]

Storage and release

[edit]

Most histamine in the body is generated in granules in mast cells and in white blood cells (leukocytes) called basophils. Mast cells are especially numerous at sites of potential injury – the nose, mouth, and feet, internal body surfaces, and blood vessels. Non-mast cell histamine is found in several tissues, including the hypothalamus region of the brain, where it functions as a neurotransmitter. Another important site of histamine storage and release is the enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cell of the stomach.

The most important pathophysiologic mechanism of mast cell and basophil histamine release is immunologic. These cells, if sensitized by IgE antibodies attached to their membranes, degranulate when exposed to the appropriate antigen. Certain amines and alkaloids, including such drugs as morphine, and curare alkaloids, can displace histamine in granules and cause its release. Antibiotics like polymyxin are also found to stimulate histamine release.

Histamine release occurs when allergens bind to mast-cell-bound IgE antibodies. Reduction of IgE overproduction may lower the likelihood of allergens finding sufficient free IgE to trigger a mast-cell-release of histamine.

Degradation

[edit]Histamine is released by mast cells as an immune response and is later degraded primarily by two enzymes: diamine oxidase (DAO), coded by AOC1 genes, and histamine-N-methyltransferase (HNMT), coded by the HNMT gene. The presence of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at these genes are associated with a wide variety of disorders, from ulcerative colitis to autism spectrum disorder (ASD).[13] Histamine degradation is crucial to the prevention of allergic reactions to otherwise harmless substances.

DAO is typically expressed in epithelial cells at the tip of the villus of the small intestine mucosa.[14] Reduced DAO activity is associated with gastrointestinal disorders and widespread food intolerances. This is due to an increase in histamine absorption through enterocytes, which increases histamine concentration in the bloodstream.[15] One study found that migraine patients with gluten sensitivity were positively correlated with having lower DAO serum levels.[16] Low DAO activity can have more severe consequences as mutations in the ABP1 alleles of the AOC1 gene have been associated with ulcerative colitis.[17] Heterozygous or homozygous recessive genotypes at the rs2052129, rs2268999, rs10156191 and rs1049742 alleles increased the risk for reduced DAO activity.[18] People with genotypes for reduced DAO activity can avoid foods high in histamine, such as alcohol, fermented foods, and aged foods, to attenuate any allergic reactions. Additionally, they should be aware whether any probiotics they are taking contain any histamine-producing strains and consult with their doctor to receive proper support [citation needed].

HNMT is expressed in the central nervous system, where deficiencies have been shown to lead to aggressive behavior and abnormal sleep-wake cycles in mice.[19] Since brain histamine as a neurotransmitter regulates a number of neurophysiological functions, emphasis has been placed on the development of drugs to target histamine regulation. Yoshikawa et al. explores how the C314T, A939G, G179A, and T632C polymorphisms all impact HNMT enzymatic activity and the pathogenesis of various neurological disorders.[15] These mutations can have either a positive or negative impact. Some patients with ADHD have been shown to exhibit exacerbated symptoms in response to food additives and preservatives, due in part to histamine release. In a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial, children with ADHD who responded with aggravated symptoms after consuming a challenge beverage were more likely to have HNMT polymorphisms at T939C and Thr105Ile.[20] Histamine's role in neuroinflammation and cognition has made it a target of study for many neurological disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD). De novo deletions in the HNMT gene have also been associated with ASD.[13]

Mast cells serve an important immunological role by defending the body from antigens and maintaining homeostasis in the gut microbiome. They act as an alarm to trigger inflammatory responses by the immune system. Their presence in the digestive system enables them to serve as an early barrier to pathogens entering the body. People who suffer from widespread sensitivities and allergic reactions may have mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), in which excessive amounts of histamine are released from mast cells, and cannot be properly degraded. The abnormal release of histamine can be caused by either dysfunctional internal signals from defective mast cells or by the development of clonal mast cell populations through mutations occurring in the tyrosine kinase Kit.[21] In such cases, the body may not be able to produce sufficient degradative enzymes to properly eliminate the excess histamine. Since MCAS is symptomatically characterized as such a broad disorder, it is difficult to diagnose and can be mislabeled as a variety of diseases, including irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia.[21]

Histamine is often explored as a potential cause for diseases related to hyper-responsiveness of the immune system. In patients with asthma, abnormal histamine receptor activation in the lungs is associated with bronchospasm, airway obstruction, and production of excess mucus. Mutations in histamine degradation are more common in patients with a combination of asthma and allergen hypersensitivity than in those with just asthma. The HNMT-464 TT and HNMT-1639 TT polymorphisms are significantly more common among children with allergic asthma, the latter of which is overrepresented in African-American children.[22]

Mechanism of action

[edit]In humans, histamine exerts its effects primarily by binding to G protein-coupled histamine receptors, designated H1 through H4.[23] As of 2015[update], histamine is believed to activate ligand-gated chloride channels in the brain and intestinal epithelium.[23][24]

| G-protein coupled receptor | Location | Function | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histamine H1 receptor |

• CNS: Expressed on the dendrites of the output neurons of the histaminergic tuberomammillary nucleus, which projects to the dorsal raphe, locus coeruleus, and additional structures. |

• CNS: Sleep-wake cycle (promotes wakefulness), body temperature, nociception, endocrine homeostasis, regulates appetite, involved in cognition |

[23][24][25][26][27] |

| Histamine H2 receptor |

• CNS: Dorsal striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen), cerebral cortex (external layers), hippocampal formation, dentate nucleus of the cerebellum |

• CNS: Not established (note: most known H2 receptor ligands are unable to cross the blood–brain barrier in sufficient concentrations to allow for neuropsychological and behavioral testing) |

[23][24][28][27] |

| Histamine H3 receptor | Located in the central nervous system and to a lesser extent peripheral nervous system tissue | Autoreceptor and heteroreceptor functions: decreased neurotransmitter release of histamine, acetylcholine, norepinephrine, serotonin. Modulates nociception, gastric acid secretion, and food intake. | [23] |

| Histamine H4 receptor | Located primarily on basophils and in the bone marrow. It is also expressed in the thymus, small intestine, spleen, and colon. | Plays a role in mast cell chemotaxis, itch perception, cytokine production and secretion, and visceral hypersensitivity. Other putative functions (e.g., inflammation, allergy, cognition, etc.) have not been fully characterized. | [23] |

| Ligand-gated ion channel | Location | Function | Sources |

| Histamine-gated chloride channel | Putatively: CNS (hypothalamus, thalamus) and intestinal epithelium | Brain: Produces fast inhibitory postsynaptic potentials Intestinal epithelium: chloride secretion (associated with secretory diarrhea) |

[23][24] |

Roles in the body

[edit]Although histamine is small compared to other biological molecules (containing only 17 atoms), it plays an important role in the body. It is known to be involved in 23 different physiological functions. Histamine is known to be involved in many physiological functions because of its chemical properties that allow it to be versatile in binding. It is Coulombic (able to carry a charge), conformational, and flexible. This allows it to interact and bind more easily.[29]

Vasodilation and fall in blood pressure

[edit]It has been known for more than one hundred years that an intravenous injection of histamine causes a fall in the blood pressure.[30] The underlying mechanism concerns both vascular hyperpermeability and vasodilation. Histamine binding to endothelial cells causes them to contract, thus increasing vascular leak. It also stimulates synthesis and release of various vascular smooth muscle cell relaxants, such as nitric oxide, endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors and other compounds, resulting in blood vessel dilation.[31] These two mechanisms play a key role in the pathophysiology of anaphylaxis.

Effects on nasal mucous membrane

[edit]Increased vascular permeability causes fluid to escape from capillaries into the tissues, which leads to the classic symptoms of washing out a poison: a runny nose and watery eyes. Poisons can bind to IgE-loaded mast cells in the nasal cavity's mucous membranes. This can lead to three clinical responses:[32]

- sneezing due to histamine-associated sensory neural stimulation

- hyper-secretion from glandular tissue

- nasal congestion due to vascular engorgement associated with vasodilation and increased capillary permeability

Sleep-wake regulation

[edit]Histamine is a neurotransmitter that is released from histaminergic neurons which project out of the mammalian hypothalamus. The cell bodies of these neurons are located in a portion of the posterior hypothalamus known as the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN). The histamine neurons in this region comprise the brain's histamine system, which projects widely throughout the brain and includes axonal projections to the cortex, medial forebrain bundle, other hypothalamic nuclei, medial septum, the nucleus of the diagonal band, ventral tegmental area, amygdala, striatum, substantia nigra, hippocampus, thalamus and elsewhere.[33] The histamine neurons in the TMN are involved in regulating the sleep-wake cycle and promote arousal when activated.[34] The neural firing rate of histamine neurons in the TMN is strongly positively correlated with an individual's state of arousal. These neurons fire rapidly during periods of wakefulness, fire more slowly during periods of relaxation/tiredness, and stop firing altogether during REM and NREM (non-REM) sleep.[35]

First-generation H1 antihistamines (i.e., antagonists of histamine receptor H1) are capable of crossing the blood–brain barrier and produce drowsiness by antagonizing histamine H1 receptors in the tuberomammillary nucleus. The newer class of second-generation H1 antihistamines do not readily permeate the blood–brain barrier and thus are less likely to cause sedation, although individual reactions, concomitant medications and dosage may increase the likelihood of a sedating effect. In contrast, histamine H3 receptor antagonists increase wakefulness. Similar to the sedative effect of first-generation H1 antihistamines, an inability to maintain vigilance can occur from the inhibition of histamine biosynthesis or the loss (i.e., degeneration or destruction) of histamine-releasing neurons in the TMN.

Gastric acid release

[edit]Enterochromaffin-like cells in the stomach release histamine, stimulating parietal cells via H2 receptors. This triggers carbon dioxide and water uptake from the blood, converted to carbonic acid by carbonic anhydrase. The acid dissociates into hydrogen and bicarbonate ions within the parietal cell. Bicarbonate returns to the bloodstream, while hydrogen ions are pumped into the stomach lumen. Histamine release ceases as stomach pH decreases.[medical citation needed] Antagonist molecules, such as ranitidine or famotidine, block the H2 receptor and prevent histamine from binding, causing decreased hydrogen ion secretion.[medical citation needed]

Protective effects

[edit]While histamine has stimulatory effects upon neurons, it also has suppressive ones that protect against the susceptibility to convulsion, drug sensitization, denervation supersensitivity, ischemic lesions and stress.[36] It has also been suggested that histamine controls the mechanisms by which memories and learning are forgotten.[37]

Erection and sexual function

[edit]This section is missing information about sexual dysfunction in females. (October 2023) |

Loss of libido and erectile dysfunction can occur during treatment with histamine H2 receptor antagonists such as cimetidine, ranitidine, and risperidone.[38] The injection of histamine into the corpus cavernosum in males with psychogenic impotence produces full or partial erections in 74% of them.[39] It has been suggested that H2 antagonists may cause sexual dysfunction by reducing the functional binding of testosterone to its androgen receptors.[38]

Schizophrenia

[edit]Metabolites of histamine are increased in the cerebrospinal fluid of people with schizophrenia, while the efficiency of H1 receptor binding sites is decreased. Many atypical antipsychotic medications have the effect of increasing histamine production.[40][medical citation needed]

Multiple sclerosis

[edit]Histamine therapy for treatment of multiple sclerosis is currently being studied. The different H receptors have been known to have different effects on the treatment of this disease. The H1 and H4 receptors, in one study, have been shown to be counterproductive in the treatment of MS. The H1 and H4 receptors are thought to increase permeability in the blood-brain barrier, thus increasing infiltration of unwanted cells in the central nervous system. This can cause inflammation, and MS symptom worsening. The H2 and H3 receptors are thought to be helpful when treating MS patients. Histamine has been shown to help with T-cell differentiation. This is important because in MS, the body's immune system attacks its own myelin sheaths on nerve cells (which causes loss of signaling function and eventual nerve degeneration). By helping T cells to differentiate, the T cells will be less likely to attack the body's own cells, and instead, attack invaders.[41]

Disorders

[edit]As an integral part of the immune system, histamine may be involved in immune system disorders[42] and allergies. Mastocytosis is a rare disease in which there is a proliferation of mast cells that produce excess histamine.[43]

Histamine intolerance is a presumed set of adverse reactions (such as flush, itching, rhinitis, etc.) to ingested histamine in food. The mainstream theory accepts that there may exist adverse reactions to ingested histamine, but does not recognize histamine intolerance as a separate condition that can be diagnosed.[44]

The role of histamine in health and disease is an area of ongoing research. For example, histamine is researched in its potential link with migraine episodes, when there is a noted elevation in the plasma concentrations of both histamine and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). These two substances are potent vasodilators, and have been demonstrated to mutually stimulate each other's release within the trigeminovascular system, a mechanism that could potentially instigate the onset of migraines. In patients with a deficiency in histamine degradation due to variants in the AOC1 gene that encodes diamine oxidase enzyme, a diet high in histamine has been observed to trigger migraines, that suggests a potential functional relationship between exogenous histamine and CGRP, which could be instrumental in understanding the genesis of diet-induced migraines, so that the role of histamine, particularly in relation to CGRP, is a promising area of research for elucidating the mechanisms underlying migraine development and aggravation, especially relevant in the context of dietary triggers and genetic predispositions related to histamine metabolism.[45]

Measurement

[edit]Histamine, a biogenic amine, involves many physiological functions, including the immune response, gastric acid secretion, and neuromodulation. However, its rapid metabolism makes it challenging to measure histamine levels directly in plasma.[46]

As a solution for the rapid metabolism of histamine, the measurement of histamine and its metabolites, particularly the 1,4-methyl-imidazolacetic acid, in a 24-hour urine sample, provides an efficient alternative to histamine measurement because the values of these metabolites remain elevated for a much longer period than the histamine itself.[47]

Commercial laboratories provide a 24-hour urine sample test for 1,4-methyl-imidazolacetic acid, the metabolite of histamine. This test is a valuable tool in assessing the metabolism of histamine in the body, as direct measurement of histamine in the serum has low diagnostic value due to the specificities of histamine metabolism.[48][49][50]

The urine test involves collecting all urine produced in a 24-hour period, which is then analyzed for the presence of 1,4-methyl-imidazolacetic acid. This comprehensive approach ensures a more accurate reflection of histamine metabolism over an extended period; as such, the 1,4-methyl-imidazolacetic acid urine test offered by commercial labs is currently the most reliable method to determine the rate of histamine metabolism, which may be helpful for the health care practitioners to assess individual's health status,[51][52] such as to diagnose interstitial cystitis.[53]

History

[edit]The properties of histamine, then called β-imidazolylethylamine, were first described in 1910 by the British scientists Henry H. Dale and P.P. Laidlaw.[54] By 1913 the name histamine was in use, using combining forms of histo- + amine, yielding "tissue amine".

"H substance" or "substance H" are occasionally used in medical literature for histamine or a hypothetical histamine-like diffusible substance released in allergic reactions of skin and in the responses of tissue to inflammation.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Histamine Material Safety Data Sheet (Technical report). sciencelab.com. 2013-05-21. Archived from the original on 2012-03-24.

- ^ a b Vuckovic D, Pawliszyn J (March 2011). "Systematic evaluation of solid-phase microextraction coatings for untargeted metabolomic profiling of biological fluids by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry". Analytical Chemistry. 83 (6): 1944–54. doi:10.1021/ac102614v. PMID 21332182.

- ^ Marieb E (2001). Human anatomy & physiology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. pp. 414. ISBN 0-8053-4989-8.

- ^ Nieto-Alamilla G, Márquez-Gómez R, García-Gálvez AM, Morales-Figueroa GE, Arias-Montaño JA (November 2016). "The Histamine H3 Receptor: Structure, Pharmacology, and Function". Molecular Pharmacology. 90 (5): 649–673. doi:10.1124/mol.116.104752. PMID 27563055.

- ^ Keppel Hesselink JM (December 2015). "The terms 'autacoid', 'hormone' and 'chalone' and how they have shifted with time". Autonomic & Autacoid Pharmacology. 35 (4): 51–8. doi:10.1111/aap.12037. PMID 27028114.

- ^ Andersen HH, Elberling J, Arendt-Nielsen L (September 2015). "Human surrogate models of histaminergic and non-histaminergic itch" (PDF). Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 95 (7): 771–7. doi:10.2340/00015555-2146. PMID 26015312. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ^ Di Giuseppe M, Fraser D (2003). Nelson Biology 12. Toronto: Thomson Canada. p. 473. ISBN 0-17-625987-2.

- ^ "Histamine". webbook.nist.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- ^ "Histamine dihydrochloride H7250". Sigma-Aldrich. Archived from the original on 2015-08-09.

- ^ "Histamine phosphate" (PDF). European Pharmacopoeia (5th ed.). ISBN 92-871-5281-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-04. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- ^ Paiva TB, Tominaga M, Paiva AC (July 1970). "Ionization of histamine, N-acetylhistamine, and their iodinated derivatives". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 13 (4): 689–92. doi:10.1021/jm00298a025. PMID 5452432.

- ^ Jayarajah CN, Skelley AM, Fortner AD, Mathies RA (November 2007). "Analysis of neuroactive amines in fermented beverages using a portable microchip capillary electrophoresis system" (PDF). Analytical Chemistry. 79 (21): 8162–9. doi:10.1021/ac071306s. PMID 17892274. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011.

- ^ a b Wright C, Shin JH, Rajpurohit A, Deep-Soboslay A, Collado-Torres L, Brandon NJ, et al. (May 2017). "Altered expression of histamine signaling genes in autism spectrum disorder". Translational Psychiatry. 7 (5): e1126. doi:10.1038/tp.2017.87. PMC 5534955. PMID 28485729.

- ^ Thompson JS (1990). "Significance of the intestinal gradient of diamine oxidase activity". Digestive Diseases. 8 (3): 163–8. doi:10.1159/000171249. PMID 2110876.

- ^ a b Yoshikawa T, Nakamura T, Yanai K (February 2019). "Histamine N-Methyltransferase in the Brain". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20 (3): 737. doi:10.3390/ijms20030737. PMC 6386932. PMID 30744146.

- ^ Griauzdaitė K, Maselis K, Žvirblienė A, Vaitkus A, Jančiauskas D, Banaitytė-Baleišienė I, et al. (September 2020). "Associations between migraine, celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity and activity of diamine oxidase". Medical Hypotheses. 142 109738. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109738. PMID 32416409. S2CID 216303896.

- ^ García-Martin E, Mendoza JL, Martínez C, Taxonera C, Urcelay E, Ladero JM, et al. (January 2006). "Severity of ulcerative colitis is associated with a polymorphism at diamine oxidase gene but not at histamine N-methyltransferase gene". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 12 (4): 615–20. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.615. PMC 4066097. PMID 16489678.

- ^ Maintz L, Yu CF, Rodríguez E, Baurecht H, Bieber T, Illig T, et al. (July 2011). "Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the diamine oxidase gene with diamine oxidase serum activities" (PDF). Allergy. 66 (7): 893–902. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02548.x. PMID 21488903. S2CID 205405463.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Branco AC, Yoshikawa FS, Pietrobon AJ, Sato MN (2018-08-27). "Role of Histamine in Modulating the Immune Response and Inflammation". Mediators of Inflammation. 2018 9524075. doi:10.1155/2018/9524075. PMC 6129797. PMID 30224900.

- ^ Stevenson J, Sonuga-Barke E, McCann D, Grimshaw K, Parker KM, Rose-Zerilli MJ, et al. (September 2010). "The role of histamine degradation gene polymorphisms in moderating the effects of food additives on children's ADHD symptoms". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 167 (9): 1108–15. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101529. PMID 20551163.

- ^ a b Haenisch B, Nöthen MM, Molderings GJ (November 2012). "Systemic mast cell activation disease: the role of molecular genetic alterations in pathogenesis, heritability and diagnostics". Immunology. 137 (3): 197–205. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03627.x. PMC 3482677. PMID 22957768.

- ^ Anvari S, Vyhlidal CA, Dai H, Jones BL (December 2015). "Genetic Variation along the Histamine Pathway in Children with Allergic versus Nonallergic Asthma". American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 53 (6): 802–9. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2014-0493OC. PMC 4742940. PMID 25909280.

- ^ a b c d e f g Panula P, Chazot PL, Cowart M, Gutzmer R, Leurs R, Liu WL, et al. (July 2015). "International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XCVIII. Histamine Receptors". Pharmacological Reviews. 67 (3): 601–55. doi:10.1124/pr.114.010249. PMC 4485016. PMID 26084539.

- ^ a b c d Wouters MM, Vicario M, Santos J (January 2016). "The role of mast cells in functional GI disorders". Gut. 65 (1): 155–68. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309151. PMID 26194403.

- ^ Blandina P, Munari L, Provensi G, Passani MB (2012). "Histamine neurons in the tuberomamillary nucleus: a whole center or distinct subpopulations?". Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 6: 33. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2012.00033. PMC 3343474. PMID 22586376.

- ^ Stromberga Z, Chess-Williams R, Moro C (March 2019). "Histamine modulation of urinary bladder urothelium, lamina propria and detrusor contractile activity via H1 and H2 receptors". Scientific Reports. 9 (1) 3899. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.3899S. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-40384-1. PMC 6405771. PMID 30846750.

- ^ a b Pal S, Gasheva OY, Zawieja DC, Meininger CM, Gashev AA J (January 2020). "Histamine mediated autocrine signalling in mesenteric perilymphatic mast cells". Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 318 (3): 590–604. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00255.2019. PMC 7099465. PMID 31913658. S2CID 210119438.

- ^ Maguire JJ, Davenport AP (29 November 2016). "H2 receptor". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ^ Noszal B, Kraszni M, Racz A (2004). "Histamine: fundamentals of biological chemistry". In Falus A, Grosman N, Darvas Z (eds.). Histamine: Biology and Medical Aspects. Budapest: SpringMed. pp. 15–28. ISBN 3-8055-7715-X.

- ^ Dale HH, Laidlaw PP (December 1910). "The physiological action of beta-iminazolylethylamine". The Journal of Physiology. 41 (5): 318–44. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1910.sp001406. PMC 1512903. PMID 16993030.

- ^ Abbas A (2018). Cellular and molecular immunology. Elsevier. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-323-47978-3.

- ^ Monroe EW, Daly AF, Shalhoub RF (February 1997). "Appraisal of the validity of histamine-induced wheal and flare to predict the clinical efficacy of antihistamines". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 99 (2): S798-806. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70128-3. PMID 9042073.

- ^ Brady S (2012). Basic Neurochemistry - Principles of Molecular, Cellular and Medical Neurobiology. Waltham, USA: Elsevier. p. 337. ISBN 978-0-12-374947-5.

- ^ Brown RE, Stevens DR, Haas HL (April 2001). "The physiology of brain histamine". Progress in Neurobiology. 63 (6): 637–72. doi:10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00039-3. PMID 11164999. S2CID 10170830.

- ^ Takahashi K, Lin JS, Sakai K (October 2006). "Neuronal activity of histaminergic tuberomammillary neurons during wake-sleep states in the mouse". The Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (40): 10292–10298. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2341-06.2006. PMC 6674640. PMID 17021184.

- ^ Yanai K, Tashiro M (January 2007). "The physiological and pathophysiological roles of neuronal histamine: an insight from human positron emission tomography studies". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 113 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.06.008. PMID 16890992.

- ^ Alvarez EO (May 2009). "The role of histamine on cognition". Behavioural Brain Research. 199 (2): 183–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.010. hdl:11336/80375. PMID 19126417. S2CID 205879131.

- ^ a b White JM, Rumbold GR (1988). "Behavioural effects of histamine and its antagonists: a review". Psychopharmacology. 95 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1007/bf00212757. PMID 3133686. S2CID 23148946.

- ^ Cará AM, Lopes-Martins RA, Antunes E, Nahoum CR, De Nucci G (February 1995). "The role of histamine in human penile erection". British Journal of Urology. 75 (2): 220–4. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1995.tb07315.x. PMID 7850330.

- ^ Ito C (2004). "The role of the central histaminergic system on schizophrenia". Drug News & Perspectives. 17 (6): 383–7. doi:10.1358/dnp.2004.17.6.829029 (inactive 11 October 2025). PMID 15334189.

Many atypical antipsychotics also increased histamine turnovers.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2025 (link) - ^ Jadidi-Niaragh F, Mirshafiey A (September 2010). "Histamine and histamine receptors in pathogenesis and treatment of multiple sclerosis". Neuropharmacology. 59 (3): 180–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.05.005. PMID 20493888. S2CID 7852375.

- ^ Zampeli E, Tiligada E (May 2009). "The role of histamine H4 receptor in immune and inflammatory disorders". British Journal of Pharmacology. 157 (1): 24–33. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00151.x. PMC 2697784. PMID 19309354.

- ^ Valent P, Horny HP, Escribano L, Longley BJ, Li CY, Schwartz LB, et al. (July 2001). "Diagnostic criteria and classification of mastocytosis: a consensus proposal". Leukemia Research. 25 (7): 603–25. doi:10.1016/S0145-2126(01)00038-8. PMID 11377686.

- ^ Reese I, Ballmer-Weber B, Beyer K, Dölle-Bierke S, Kleine-Tebbe J, Klimek L, Lämmel S, Lepp U, Saloga J, Schäfer C, Szepfalusi Z, Treudler R, Werfel T, Zuberbier T, Worm M (2021). "Guideline on management of suspected adverse reactions to ingested histamine: Guideline of the German Society for Allergology and Clinical Immunology (DGAKI), the Society for Pediatric Allergology and Environmental Medicine (GPA), the Medical Association of German Allergologists (AeDA) as well as the Swiss Society for Allergology and Immunology (SGAI) and the Austrian Society for Allergology and Immunology (ÖGAI)". Allergol Select. 5: 305–314. doi:10.5414/ALX02269E. PMC 8511827. PMID 34651098.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ De Mora F, Messlinger K (2024). "Is calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) the missing link in food histamine-induced migraine? A review of functional gut-to-trigeminovascular system connections". Drug Discovery Today. 29 (4) 103941. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2024.103941. PMID 38447930.

- ^ Comas-Basté O, Latorre-Moratalla M, Bernacchia R, Veciana-Nogués M, Vidal-Carou M (2017). "New approach for the diagnosis of histamine intolerance based on the determination of histamine and methylhistamine in urine". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 145: 379–385. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2017.06.029. hdl:2445/163026. PMID 28715791.

- ^ Tham R (1966). "Gas chromatographic analysis of histamine metabolites in urine". Journal of Chromatography A. 23 (2): 207–216. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(01)98675-3. PMID 4165374.

- ^ Nelis M, Decraecker L, Boeckxstaens G, Augustijns P, Cabooter D (2020). "Development of a HILIC-MS/MS method for the quantification of histamine and its main metabolites in human urine samples". Talanta. 220 121328. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121328. PMID 32928382.

- ^ "2-(1-methyl-1H-imidazol-4-yl)acetic acid". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 18 August 2024. Retrieved 2024-08-18.

- ^ Bähre H, Kaever V (2017). "Analytical Methods for the Quantification of Histamine and Histamine Metabolites". Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 241: 3–19. doi:10.1007/164_2017_22. ISBN 978-3-319-58192-7. PMID 28321587.

- ^ Comas-Basté O, Latorre-Moratalla M, Bernacchia R, Veciana-Nogués M, Vidal-Carou M (2017). "New approach for the diagnosis of histamine intolerance based on the determination of histamine and methylhistamine in urine". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 145: 379–385. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2017.06.029. hdl:2445/163026. PMID 28715791.

- ^ Yun SK, Laub DJ, Weese DL, Lad PM, Leach GE, Zimmern PE (1992). "Stimulated Release of Urine Histamine in Interstitial Cystitis". Journal of Urology. 148 (4): 1145–1148. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)36844-1. PMID 1404625.

- ^ El-Mansoury M, Boucher W, Sant G, Theoharides T (1994). "Increased Urine Histamine and Methylhistamine in Interstitial Cystitis". Journal of Urology. 152 (2 Part 1): 350–353. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)32737-4. PMID 8015069.

- ^ Dale HH, Laidlaw PP (December 1910). "The physiological action of beta-iminazolylethylamine". The Journal of Physiology. 41 (5): 318–44. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1910.sp001406. PMC 1512903. PMID 16993030.[permanent dead link]

External links

[edit]Histamine

View on GrokipediaChemical Properties

Molecular Structure

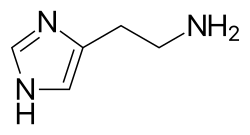

Histamine possesses the molecular formula C5H9N3 and consists of an imidazole ring linked to an ethylamine side chain at the 4-position of the ring.[4] Its systematic IUPAC name is 2-(1H-imidazol-4-yl)ethanamine, reflecting the substitution pattern where the ethylamine chain (-CH2CH2NH2) extends from the imidazole core.[4] The imidazole ring in histamine is a five-membered heterocyclic structure containing two nitrogen atoms, which enables prototropic tautomerism. This involves the reversible migration of a proton between the N1 and N3 positions, resulting in two equivalent tautomeric forms that interconvert rapidly in solution.[5] Such tautomerism contributes to the molecule's flexibility and influences its interactions in biological contexts. As a biogenic amine, histamine is formed via the decarboxylation of the amino acid histidine, setting it apart structurally from other biogenic amines like the catecholamines (e.g., dopamine and norepinephrine), which are based on a benzene ring with catechol substituents, and serotonin, which features an indole ring system.[6][7] The distinct imidazole ring imparts unique chemical properties to histamine compared to these counterparts. Key acid dissociation constants (pKa values) for histamine are 9.68 for the aliphatic amine group and 5.88 for the imidazole ring, with the latter's protonation at physiological pH serving as a critical site for interactions such as receptor binding.[4]Physical and Chemical Characteristics

Histamine appears as a colorless to white crystalline solid at room temperature, often in the form of long prismatic crystals that are odorless and deliquescent.[4] Its molecular weight is 111.15 g/mol.[4] The compound exhibits high solubility in water, approximately 1 g dissolving in 4 mL, and is freely soluble in ethanol and hot chloroform, but sparingly soluble or insoluble in non-polar solvents such as diethyl ether.[4] This solubility profile arises from its polar imidazole ring and primary amine group, which facilitate interactions with polar solvents.[4] Histamine demonstrates sensitivity to light and oxidation, with solutions degrading upon exposure to fluorescent light unless protected, and it is also hygroscopic and affected by air.[8][9] It melts at 83–84 °C and boils at approximately 209–210 °C under reduced pressure (18 mm Hg), decomposing above 200 °C.[10][4] Stability in aqueous solution is pH-dependent, with optimal preservation under neutral to slightly acidic conditions when shielded from light and oxidants.[8] As a basic amine, histamine readily forms salts such as histamine dihydrochloride and phosphate, which are commonly used for its handling and storage due to improved stability compared to the free base.[4]Biosynthesis and Metabolism

Synthesis in the Body

Histamine is primarily synthesized in the body through the decarboxylation of the amino acid L-histidine, a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme histidine decarboxylase (HDC).[11] This process removes the carboxyl group from L-histidine, yielding histamine and carbon dioxide as byproducts.[12] HDC is a pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzyme, relying on this vitamin B6-derived cofactor for its activity.[13] The biochemical reaction can be represented as: This one-step pathway is the sole mechanism for endogenous histamine production, with no alternative enzymatic routes identified in mammals.[14] Synthesis occurs predominantly in specific cell types, including mast cells and basophils in the immune system, enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells in the gastric mucosa, and histaminergic neurons in the central nervous system.[15] The expression of the HDC gene is tightly regulated at the transcriptional level, influenced by factors such as cytokine signaling and transcriptional activators that bind to promoter regions.[6] HDC activity and gene expression are upregulated during inflammatory responses and allergic conditions, leading to increased histamine production to modulate immune functions.[16] For instance, pro-inflammatory stimuli like lipopolysaccharide can expand HDC-expressing cell populations in tissues.[17] In contrast, dietary histamine from food sources contributes minimally to systemic levels in healthy individuals, as it is rapidly degraded by enzymes such as diamine oxidase and histamine N-methyltransferase upon absorption.[18] Thus, de novo synthesis via HDC remains the dominant source for physiological histamine needs. The synthesized histamine is subsequently stored in intracellular granules for regulated release.[19]Enzymatic Degradation

Histamine is primarily inactivated through two enzymatic pathways that ensure its rapid clearance from tissues, preventing excessive accumulation and prolonged physiological effects. The primary extracellular pathway involves diamine oxidase (DAO), a copper-containing enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative deamination of histamine. This process converts histamine to imidazole-4-acetaldehyde, ammonia, and hydrogen peroxide, with the aldehyde intermediate subsequently oxidized to imidazole-4-acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase.[20] The reaction can be represented as: DAO is predominantly expressed in the intestinal mucosa, kidneys, and placenta, where it plays a crucial role in degrading dietary histamine and preventing its systemic absorption.[21] The alternative intracellular pathway is mediated by histamine N-methyltransferase (HNMT), which transfers a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to the imidazole ring of histamine, yielding Nτ-methylhistamine and S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH). This methylated product is then oxidatively deaminated by monoamine oxidase (MAO), primarily MAO-B, to N-methylimidazole-4-acetaldehyde, which is further metabolized to N-methylimidazole-4-acetic acid.[22] The initial methylation step is depicted as: HNMT is widely distributed, with high expression in the brain, liver, and kidneys, making it essential for regulating histamine levels in neural and hepatic tissues.[21] Genetic variations in the DAO gene (AOC1) can lead to reduced enzyme activity, impairing histamine breakdown and contributing to elevated histamine levels in affected individuals.[21] Similarly, polymorphisms in the HNMT gene have been associated with altered methylation efficiency, though DAO variants are more commonly linked to metabolic deficiencies.[21]Cellular Handling

Storage Mechanisms

Histamine is primarily stored in secretory granules within mast cells and basophils, where it constitutes a significant portion of the granule content.[23] In these immune cells, histamine levels can reach 1–3 μg per 10^6 cells, reflecting their role as major reservoirs. Additionally, in histaminergic neurons located in the tuberomammillary nucleus of the hypothalamus, histamine is packaged into synaptic vesicles via the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) for regulated neurotransmission. In enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells of the gastric mucosa, histamine is stored in cytoplasmic granules, synthesized locally from L-histidine and accumulated through proton-histamine countertransport mediated by VMAT2.[26] Within the acidic environment of mast cell and basophil granules (pH ≈5.5), histamine becomes protonated, enabling stable electrostatic binding to negatively charged proteoglycans such as heparin and chondroitin sulfate, which form an anionic matrix essential for mediator retention.[27] This pH-dependent interaction, facilitated by serglycin core proteins, prevents premature leakage and maintains high intragranular concentrations.[28] Uptake of newly synthesized or exogenous histamine into these storage compartments is regulated by organic cation transporters (OCTs), particularly OCT3 (encoded by SLC22A3), which mediates bidirectional transport across the plasma membrane in mast cells.[29] In contrast to granular storage in immune and neural cells, histamine in enterocytes is synthesized on demand for localized paracrine signaling in the gastrointestinal tract, without packaging into storage vesicles.[30]Release Triggers

Histamine release primarily occurs from mast cells and basophils in the periphery, as well as from histaminergic neurons in the central nervous system, through distinct stimulus-dependent mechanisms.[31] Immunological triggers involve IgE-mediated degranulation in mast cells, where allergens crosslink IgE antibodies bound to the high-affinity receptor FcεRI on the cell surface, initiating intracellular signaling cascades that lead to rapid histamine efflux.[31] This process is central to type I hypersensitivity reactions and requires antigen-specific IgE for activation.[32] Non-immunological triggers bypass IgE and directly stimulate mast cell degranulation through diverse physical, chemical, or pharmacological agents. Physical stimuli, such as heat or mechanical pressure, can provoke histamine release by altering membrane integrity or activating sensory pathways that indirectly engage mast cells.[33] Chemical agents like certain venoms from insects or snakes induce degranulation via toxin-mediated membrane perturbation or receptor activation, leading to mediator discharge.[34] Pharmacological compounds, including opioids such as morphine and synthetic agents like compound 48/80, cause direct mast cell activation independent of immune pathways, often through G-protein-coupled receptor interactions or membrane disruption.[35][36] In the central nervous system, histamine is released from neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus of the posterior hypothalamus via calcium-dependent exocytosis, triggered by action potentials that open voltage-gated calcium channels, allowing vesicular fusion with the plasma membrane. Feedback regulation of neuronal histamine release occurs through presynaptic H3 receptors on histaminergic neurons, which mediate autoinhibition to prevent excessive transmitter output; activation of these autoreceptors reduces calcium influx and suppresses further exocytosis.[37] Histamine release from storage granules in mast cells can follow quantal patterns, including full granule exocytosis where entire granules fuse with the membrane to discharge contents en masse, or piecemeal degranulation involving selective, partial emptying of vesicles without complete fusion, allowing graded mediator output.[38]Receptors and Signaling

Types of Histamine Receptors

Histamine mediates its physiological effects by binding to four distinct subtypes of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), known as H₁, H₂, H₃, and H₄ receptors. These receptors are encoded by separate genes and exhibit tissue-specific expression patterns, with histamine acting as the endogenous agonist for all subtypes through interactions involving its imidazole ring and ethylamine side chain. The binding affinity of histamine varies among the receptors, with H₃ and H₄ subtypes displaying higher potency (lower dissociation constants) compared to H₁ and H₂.[39][40] The H₁ receptor is coupled to the Gq/11 protein family, leading to activation of phospholipase C and subsequent increases in intracellular calcium and inositol phosphates. It is widely distributed in smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, neurons, and the central nervous system (CNS), as well as in peripheral tissues such as the airways and vasculature. This receptor is prominently involved in mediating classic allergic responses, including bronchoconstriction and vasodilation.[1][3][39] In contrast, the H₂ receptor couples to the stimulatory G protein (Gs), which activates adenylyl cyclase to increase cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels. It is primarily expressed in gastric parietal cells, cardiac tissue, vascular smooth muscle, and certain immune cells like mast cells and lymphocytes. The H₂ receptor plays a key role in gastric acid secretion and cardiac function regulation.[1][3][39] The H₃ receptor is coupled to inhibitory G proteins (Gi/o), resulting in decreased cAMP production and modulation of other signaling pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). It functions mainly as a presynaptic autoreceptor on histaminergic neurons in the CNS, particularly in the tuberomamillary nucleus of the hypothalamus, and is also found in peripheral neurons. This receptor inhibits the release of histamine and other neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin.[1][3][39] The H₄ receptor, like H₃, couples to Gi/o proteins, inhibiting adenylyl cyclase and also mobilizing intracellular calcium in some contexts. It is predominantly expressed in hematopoietic and immune cells, including eosinophils, mast cells, dendritic cells, and T-cells, with lower levels in the gastrointestinal tract and spleen. The H₄ receptor contributes to immune cell chemotaxis and recruitment during inflammatory processes.[1][3][39]Intracellular Signaling Pathways

Histamine receptors, as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), initiate diverse intracellular signaling cascades upon ligand binding, primarily through G-protein activation that modulates second messenger systems and downstream kinases. These pathways vary by receptor subtype and contribute to histamine's multifaceted physiological effects, with key mechanisms involving phospholipase C (PLC), adenylyl cyclase (AC), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways.[41] The H1 receptor couples to Gαq/11 proteins, activating PLC to hydrolyze phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 binds to receptors on the endoplasmic reticulum, triggering Ca²⁺ release into the cytosol, while DAG recruits and activates protein kinase C (PKC), which phosphorylates target proteins to amplify signaling. This Ca²⁺-PKC axis is central to H1-mediated responses such as smooth muscle contraction and increased vascular permeability.[41] In contrast, the H2 receptor engages Gαs proteins to stimulate AC, elevating cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels, which in turn activates protein kinase A (PKA). PKA phosphorylates substrates involved in processes like gastric acid secretion and vasodilation, providing a counter-regulatory influence to H1 signaling in certain contexts.[41] The H3 and H4 receptors couple to inhibitory Gαi/o proteins, suppressing AC activity and thereby reducing cAMP production and PKA activation, which modulates neurotransmitter release and immune cell function, respectively. Additionally, both subtypes can engage MAPK/ERK pathways; for instance, H4 activation rapidly phosphorylates ERK1/2 in mast cells, enhancing cytokine production such as IL-6, while H3 stimulation transiently activates ERK in striatal neurons, influencing synaptic plasticity.[41][42][43] To prevent prolonged signaling, histamine receptors undergo desensitization via phosphorylation by G-protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs), particularly GRK2/3/5/6 for H1, followed by β-arrestin recruitment, which uncouples the receptor from G-proteins and promotes clathrin-mediated internalization. For H1, β-arrestin binding facilitates receptor endocytosis, with recovery occurring through de novo synthesis or recycling, thereby regulating the duration of Ca²⁺ mobilization and downstream effects.[44] Histamine receptor signaling exhibits cross-talk with other GPCRs, such as bradykinin receptors, where their activations lead to synergistic amplification of endothelial permeability through shared pathways like Ca²⁺ signaling and actin cytoskeleton rearrangement to promote vascular leakage.[45]Physiological Functions

Immune and Inflammatory Roles

Histamine plays a central role in modulating immune responses and inflammation, primarily through its release from mast cells and basophils during degranulation triggered by IgE-mediated activation or pathogen recognition. As a key mediator, it promotes vascular permeability to facilitate leukocyte recruitment and influences cytokine production, thereby bridging innate and adaptive immunity.[46] In allergic reactions, histamine binds to H1 receptors on sensory nerves and endothelial cells, inducing itch and the characteristic wheal-and-flare response via phospholipase C activation, which increases intracellular calcium and promotes smooth muscle contraction and vasodilation.[47] Additionally, H4 receptor activation enhances eosinophil chemotaxis and adhesion, recruiting these cells to amplify type 2 immune responses in tissues like the airways and skin.[46] In inflammatory processes, histamine increases vascular permeability through H1 receptor signaling, enabling leukocyte extravasation by loosening endothelial junctions and upregulating adhesion molecules such as P-selectin and ICAM-1.[47] H2 receptors on macrophages modulate cytokine release, elevating anti-inflammatory IL-10 while suppressing pro-inflammatory TNF-α and IL-12 via cAMP-dependent protein kinase A pathways, thus fine-tuning the inflammatory milieu to prevent excessive tissue damage.[47] This dual regulation helps balance acute inflammation for pathogen clearance. Regarding innate immunity, mast cell degranulation in response to pathogens occurs via pattern recognition receptors like TLR2, releasing histamine to enhance antimicrobial defenses.[48] Histamine's effects on immune cells, mediated by H1 and H4 receptors, further support early defense by promoting chemotaxis of innate effectors like monocytes.[46] In chronic inflammation, sustained H1 and H4 signaling contributes to conditions like asthma and atopic dermatitis by perpetuating Th2-dominated responses, including IL-5-driven eosinophilia and IL-31-mediated pruritus, which recruit natural killer cells and sustain tissue remodeling.[47]Cardiovascular and Vascular Effects

Histamine exerts profound effects on the cardiovascular system primarily through its interactions with H1 and H2 receptors, leading to vasodilation and alterations in blood pressure. Activation of H1 receptors on vascular endothelial cells stimulates the release of nitric oxide (NO), which diffuses to adjacent smooth muscle cells, promoting relaxation and subsequent vasodilation. This mechanism is evidenced by histamine's upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression and activity in human vascular endothelial cells, resulting in increased NO production that supports vasoprotective effects under normal conditions.[49] In systemic circulation, this H1-mediated vasodilation, particularly of venules, contributes to hypotension by reducing peripheral resistance and venous return.[50] A hallmark of histamine's vascular action is the triple response observed in skin upon intradermal injection, first described by Lewis, consisting of localized reddening due to capillary dilation, a surrounding flare from arteriolar dilation, and wheal formation from edema. This response is mediated by H1 receptors and exemplifies histamine's role in acute inflammatory vasodilation and permeability changes. Systemically, similar venodilation exacerbates hypotension during conditions like anaphylaxis, where histamine release from mast cells triggers widespread vascular effects.[51][50] Histamine also influences cardiac function predominantly via H2 receptors, which couple to Gs proteins and elevate cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels in atrial and ventricular myocytes. This leads to positive chronotropic effects by increasing the heart rate through enhanced funny current (If) in pacemaker cells and positive inotropic effects by boosting contractility via phosphorylation of L-type calcium channels and phospholamban. These actions are prominent in atrial preparations, where H2 stimulation increases beating rate and force of contraction, as demonstrated in human and guinea pig models.[52] Increased capillary permeability is another key vascular effect of histamine, driven by H1 receptor activation that induces endothelial cell contraction and disruption of adherens junctions, allowing plasma extravasation and edema formation. This process is amplified by NO-dependent vasodilation, which elevates blood flow and shear stress on the endothelium, further promoting leakage in postcapillary venules.[53] In response to histamine-induced hypotension, counter-regulatory mechanisms activate, including reflex tachycardia mediated by baroreceptor stimulation and sympathetic outflow, which helps maintain cardiac output despite reduced vascular tone.[50] Presynaptic H3 receptors on sympathetic nerve endings in blood vessels and the heart provide autoregulatory modulation by inhibiting norepinephrine release, thereby attenuating neurogenic vasoconstriction and cardiostimulation. This H3-mediated inhibition is activated by endogenous histamine and may play a role in regulating basal blood pressure and responses in conditions like hypertension, where vascular H3 receptors interact with alpha-2 adrenoceptors to fine-tune autoregulation.[54]Gastrointestinal Regulation

Histamine plays a central role in gastric acid secretion by binding to H2 receptors on parietal cells in the stomach lining. This binding activates adenylate cyclase via G-protein-coupled signaling, leading to increased intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels, which in turn stimulate the H+/K+ ATPase proton pump to secrete hydrochloric acid into the gastric lumen.[55] This process is essential for digestion and pathogen defense in the stomach.[56] Enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells in the gastric mucosa serve as the primary source of histamine for acid secretion, releasing it in response to gastrin stimulation from G cells in the antrum. Gastrin binds to cholecystokinin B receptors on ECL cells, triggering rapid histamine release that amplifies parietal cell activation and maximizes acid output, acting as a key intermediary in the gastrin-histamine axis.[26] This ECL-mediated mechanism ensures coordinated regulation of gastric acidity during meals.[57] In the intestines, histamine modulates smooth muscle contractility and motility through H1 and H2 receptors, influencing peristalsis and transit. Activation of H1 receptors promotes contraction of longitudinal smooth muscle, while H2 receptors can induce relaxation in circular muscle layers, contributing to balanced propulsion of contents.[58] At physiological concentrations, histamine also enhances the protective mucosal barrier by inhibiting bacterial translocation across epithelial cells and supporting tissue repair, thereby maintaining gut integrity.[59] Mast cell-derived histamine is implicated in gut hypersensitivity during food allergies, where IgE-mediated degranulation leads to increased release and heightened visceral sensitivity, manifesting as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and altered motility.[60] In allergic individuals, this histamine surge exacerbates epithelial permeability and inflammatory responses in the intestinal mucosa.[61] Emerging research highlights histamine's interaction with the gut microbiome via H4 receptors, where bacterial production of histamine recruits mast cells and influences microbial composition, potentially contributing to dysbiosis and visceral hyperalgesia in disorders like irritable bowel syndrome.[62]Neurological and Behavioral Effects

Histamine serves as a key neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, primarily synthesized and released by neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) of the posterior hypothalamus. These histaminergic neurons project widely to brain regions including the cortex and hippocampus, where histamine promotes wakefulness through activation of postsynaptic H1 receptors, which excite target neurons via Gq-protein-coupled signaling leading to phospholipase C activation and increased neuronal excitability. Additionally, presynaptic H3 receptors on TMN neurons act as autoreceptors to inhibit histamine release, and their blockade by inverse agonists enhances histaminergic tone, further supporting arousal states.[63][64][63] In sleep regulation, histamine exerts a wake-promoting effect that antagonizes sleep induction; blockade of central H1 receptors by first-generation antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine, crosses the blood-brain barrier and induces sedation by reducing histaminergic excitation in arousal centers like the cortex and thalamus. This mechanism underlies the drowsiness associated with these drugs, contrasting with second-generation antihistamines that minimally penetrate the brain and thus cause less sedation. Histamine also modulates circadian rhythms, with TMN neuronal activity peaking during wake periods and influencing suprachiasmatic nucleus function to align sleep-wake cycles.[65][66][63] Regarding cognition, histamine facilitates attention and memory processes through H3 receptor modulation; H3 inverse agonists, such as pitolisant, enhance acetylcholine and dopamine release in prefrontal and hippocampal circuits by blocking presynaptic autoinhibition, thereby improving attentional performance in preclinical models of cognitive impairment. In the context of motion sickness, histamine contributes to nausea and emesis by activating H1 receptors in the area postrema, a circumventricular organ lacking a blood-brain barrier that serves as a chemoreceptor trigger zone for vestibular inputs.[67][68][69] In neuropsychiatric conditions, altered histamine signaling interacts with dopamine pathways in schizophrenia, where elevated brain histamine levels and H3 receptor dysregulation may exacerbate dopaminergic hyperactivity in mesolimbic circuits, contributing to positive symptoms; H3 antagonists have shown potential to normalize this interplay by modulating dopamine release in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. In multiple sclerosis, histamine influences demyelination processes, with H1 and H2 receptor activation promoting inflammation and oligodendrocyte damage in active lesions, while H3 receptor blockade enhances remyelination by supporting oligodendrocyte precursor differentiation and myelin repair in preclinical studies.[70][71][72][73]Clinical and Pathological Aspects

Allergic and Hypersensitivity Disorders

Histamine plays a central role in type I hypersensitivity reactions, which are IgE-mediated immune responses triggered by allergens binding to IgE antibodies on the surface of mast cells and basophils. Upon re-exposure to the allergen, cross-linking of IgE-FcεRI complexes leads to rapid degranulation, releasing histamine and other mediators that initiate immediate allergic symptoms. This IgE-mast cell axis is fundamental to conditions such as anaphylaxis, urticaria, and allergic rhinitis, where histamine's effects predominate in the early phase of the response.[74] In anaphylaxis, a severe systemic type I reaction, histamine induces widespread vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and smooth muscle contraction, resulting in hypotension, tissue edema, and potentially life-threatening respiratory compromise. Approximately 90% of anaphylactic episodes involve cutaneous or mucosal manifestations like urticaria, while 85% feature respiratory symptoms due to histamine-driven effects. Urticaria, or hives, arises from localized histamine release causing dermal vasodilation and fluid extravasation, leading to transient, pruritic wheals that typically resolve within 24 hours. Allergic rhinitis, affecting about 25.7% of adults and 18.9% of children, involves histamine-mediated nasal mucosal inflammation, promoting sneezing, congestion, and rhinorrhea through similar vascular and glandular mechanisms.[74][74][74] The hallmark symptoms of these histamine-mediated reactions—pruritus, edema, and bronchoconstriction—are primarily driven by activation of H1 receptors. Pruritus results from H1 receptor stimulation on sensory nerve endings, eliciting intense itching in affected skin or mucosa. Edema forms due to H1-mediated increases in vascular permeability, allowing plasma leakage into tissues and causing swelling in areas like the airways or dermis. Bronchoconstriction occurs via H1 receptors on bronchial smooth muscle, narrowing airways and contributing to wheezing or dyspnea, particularly in anaphylaxis or rhinitis. These effects stem from H1 receptor signaling through Gq proteins, which activate phospholipase C and elevate intracellular calcium, promoting the physiological responses.[1][1][1] Diagnosis of type I hypersensitivity often relies on skin prick tests (SPTs), which assess IgE sensitization by introducing allergens into the skin and observing the wheal-and-flare response mediated by histamine release from mast cells. A positive histamine control (typically 10 mg/mL histamine phosphate) produces a wheal of at least 3 mm to confirm skin reactivity, while allergen-induced wheals ≥3 mm larger than the negative saline control indicate allergy, measured at 15-20 minutes post-application. This method's sensitivity and specificity make it a cornerstone for identifying triggers in anaphylaxis, urticaria, and rhinitis.[75][75] The prevalence of allergic and hypersensitivity disorders has risen globally over recent decades, attributed to environmental factors such as climate change, air pollution, and altered microbiota. Global warming has increased pollen seasons and concentrations, exacerbating rhinitis and asthma, while pollutants like ozone and particulate matter heighten sensitization and symptom severity. Reduced microbial diversity from urbanization, antibiotic overuse, and cesarean deliveries further promotes Th2-skewed immune responses underlying these conditions. In children, atopic dermatitis and asthma incidence has surged since the 1990s.[76][76][76] Emerging research highlights the potential of H4 receptor-targeted therapies to address limitations in current H1-focused treatments for allergic disorders. The H4 receptor, expressed on mast cells and immune cells, amplifies inflammation, chemotaxis, and pruritus in conditions like atopic dermatitis and asthma. Selective H4 antagonists, such as JNJ 39758979 and toreforant (JNJ 38518168), have shown efficacy in preclinical models and early clinical trials, reducing pruritus and eosinophilia when combined with H1 antagonists. Post-2015 developments include phase 2 trials for toreforant in asthma and psoriasis, but results were mixed—the asthma trial showed no significant benefit, while the psoriasis trial indicated modest improvements without meeting primary endpoints—positioning H4 modulation as a promising but challenging adjunct for refractory hypersensitivity.[77][77][78][79]Histamine-Related Diseases

Histamine intolerance arises from an impaired capacity to degrade histamine, primarily due to deficiencies in the enzymes diamine oxidase (DAO) and histamine N-methyltransferase (HNMT), leading to accumulation following dietary exposure to histamine-rich foods. Histamine in these foods forms naturally through bacterial decarboxylation of the amino acid histidine, particularly in fermented, aged, or spoiled products such as cheese, wine, cured meats, and certain fish.[80][21] Common symptoms include flushing, migraines (reported in up to 87% of affected individuals with low DAO levels), triggered by foods like aged cheese or fermented products that elevate histamine intake.[21] Gastrointestinal manifestations, such as dyspepsia characterized by postprandial fullness, bloating, and abdominal discomfort, affect 55-73% of patients and stem from histamine's stimulation of smooth muscle contraction and secretion in the digestive tract.[60] Mast cell disorders, particularly systemic mastocytosis, involve clonal proliferation of mast cells leading to excessive histamine release and subsequent dysregulation.[81] In indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM), elevated mast cell burdens in bone marrow and tissues result in anaphylactoid reactions, which may include episodic flushing due to histamine-mediated vasodilation, occurring in up to 86% of cases with bone marrow involvement.[82] Anaphylactoid reactions, mimicking anaphylaxis without IgE mediation, arise from sudden degranulation releasing high histamine levels, causing hypotension and gastrointestinal distress like dyspepsia from hypersecretion.[83] These events are often triggered by non-immunologic factors such as physical stress or certain medications, highlighting histamine's central role in the disorder's morbidity.[84] In neurological conditions, histamine dysregulation contributes to pathophysiology through receptor-mediated effects. Schizophrenia is associated with hyperactivity of histaminergic neurons, evidenced by elevated levels of the histamine metabolite tele-methylhistamine in cerebrospinal fluid, suggesting increased turnover and release.[85] Deficits in H2 receptors on glutamatergic neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex lead to schizophrenia-like phenotypes, including hyperactivity, social withdrawal, and cognitive impairments, by enhancing hyperpolarization-activated currents that reduce neuronal firing.[86] In multiple sclerosis (MS), elevated histamine in cerebrospinal fluid promotes inflammation via H1 and H2 receptors, which exacerbate blood-brain barrier permeability and Th1/Th17 immune responses in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis models.[87] Blocking H1 and H2 receptors reduces disease severity by limiting cytokine production like IFN-γ and IL-17, positioning them as propathogenic targets distinct from the protective roles of H3 and H4 receptors.[88] Beyond these, histamine plays a detrimental role in other systemic conditions. In sepsis-induced shock, endogenous histamine aggravates end-organ injury in the lungs, liver, and kidneys by activating H1 and H2 receptors, leading to enhanced NF-κB-driven inflammation and cytokine storms like IL-6 and TNF-α elevation.[89] Histidine decarboxylase knockout models demonstrate reduced tissue injury and improved survival, underscoring histamine's contribution to septic pathophysiology.[89] For gastric ulcers, overactivity of H2 receptors on parietal cells drives excessive hydrochloric acid secretion, promoting mucosal erosion, particularly under stress or with aspirin co-exposure, as evidenced by H2 antagonists like metiamide preventing ulceration in rodent models.[90] This hypersecretion mechanism links histamine directly to peptic ulcer formation.[91] Emerging 2020s research indicates histamine dysregulation in long COVID symptoms, with antihistamine therapy alleviating manifestations like fatigue, dysautonomia, and cardiovascular issues by blocking H1 and H2 receptors. As of 2025, studies continue to explore antihistamine therapies, including intranasal H1 antagonists, for preventing infections and alleviating persistent symptoms.[92][93][94] In post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, elevated histamine contributes to persistent inflammation, as H2 antagonists have shown benefits in halting symptom progression in critically ill cohorts.[95] These findings highlight histamine's role in the chronic phase, though mechanisms remain under investigation.[92]Therapeutic Modulation

Therapeutic modulation of histamine involves pharmacological agents that target its receptors, synthesis, release, or degradation to manage various conditions. Antihistamines, the most common class, competitively inhibit histamine binding to specific receptors, thereby attenuating its physiological effects. These agents are classified based on the histamine receptor subtypes they target, with H1 and H2 antagonists being clinically established, while H3 and H4 modulators represent emerging therapies.[96][97] H1 receptor antagonists, or H1 blockers, are widely used to alleviate allergic responses by blocking histamine's actions on H1 receptors in smooth muscle, endothelium, and sensory nerves. First-generation agents like diphenhydramine cross the blood-brain barrier, providing rapid relief from symptoms such as itching and rhinitis but often causing sedation. Second-generation H1 blockers, including cetirizine and loratadine, are non-sedating and preferred for chronic use in allergic rhinitis and urticaria due to their selectivity and longer half-life.[96][98][99] H2 receptor antagonists inhibit gastric acid secretion by competitively blocking H2 receptors on parietal cells, making them effective for treating peptic ulcers and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ranitidine, a prototypical H2 blocker, reduces basal and nocturnal acid output, promoting ulcer healing with fewer side effects than earlier agents like cimetidine. Although ranitidine was withdrawn in some markets due to safety concerns, alternatives like famotidine continue to be used for similar indications.[97][100][101] For H3 receptors, primarily located in the central nervous system, inverse agonists like pitolisant enhance histamine release by blocking autoreceptors, increasing wakefulness. Pitolisant is approved for treating excessive daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy, with clinical trials demonstrating reduced sleepiness and cataplexy at doses up to 36 mg/day. H4 receptor antagonists, targeting immune cells, show promise in preclinical and early clinical studies for inflammatory conditions by modulating eosinophil recruitment and cytokine release, although several candidates underwent phase II trials in the 2010s, development has not progressed significantly, with ongoing research primarily in preclinical stages as of 2025.[102][103] Mast cell stabilizers, such as cromolyn sodium, prevent histamine release by inhibiting degranulation triggered by allergens or other stimuli, without directly affecting receptor binding. Cromolyn is administered prophylactically for asthma and allergic conjunctivitis, stabilizing mast cell membranes and reducing mediator release like histamine and leukotrienes.[104][105] Diamine oxidase (DAO) supplements address histamine intolerance by augmenting the enzyme responsible for degrading dietary histamine in the gut. Oral DAO supplementation has been shown to improve symptoms like headaches and gastrointestinal distress in patients with low endogenous DAO activity, particularly when combined with a low-histamine diet.[106][107]Detection and Analysis

Biochemical Measurement Techniques

Biochemical measurement techniques for histamine primarily involve sensitive analytical methods to quantify the amine in biological samples such as tissues, plasma, and urine, where concentrations are typically low (picograms to nanograms per milliliter). These methods address histamine's chemical properties, including its basic nature and reactivity, while mitigating interference from structurally similar biogenic amines like putrescine or cadaverine. Common approaches include spectrofluorometric, radioenzymatic, and chromatographic techniques, each offering distinct advantages in sensitivity, specificity, and applicability to different sample types. The spectrofluorometric assay, first described in 1959, relies on the condensation of histamine with o-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) under alkaline conditions to form a highly fluorescent isoindole derivative, which is then excited at approximately 360 nm and emits at 450-500 nm for detection. This method involves extraction of histamine from acidified samples (e.g., using perchloric acid) into butanol to separate it from proteins and interfering substances, followed by re-extraction into an acidic aqueous phase before derivatization. It achieves a sensitivity of about 1 ng/mL, making it suitable for tissue homogenates, though it requires careful pH control to avoid non-specific fluorescence from other amines. Enzymatic methods, particularly radioenzymatic assays, utilize histamine N-methyltransferase (HNMT) to catalyze the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl-L-[methyl-³H]methionine to histamine, producing radiolabeled 3H-Nτ-methylhistamine, which is then extracted and quantified by liquid scintillation counting. Developed in the early 1970s, this assay offers high sensitivity (down to 10-50 pg) and specificity, as HNMT selectively methylates histamine; samples are typically pretreated with acid to inactivate endogenous enzymes. It is widely used for plasma and urine analysis but involves handling radioactive materials, necessitating specialized facilities.[108] High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with electrochemical detection (ECD) separates histamine from biological matrices using reversed-phase columns (e.g., C18) under ion-pair conditions, with detection based on histamine's oxidation at a glassy carbon electrode poised at +0.65 V versus Ag/AgCl. This technique is particularly effective for plasma and urine, where histamine levels are sub-nanomolar, achieving limits of detection around 0.1-0.5 ng/mL after solid-phase extraction cleanup; it provides baseline resolution from metabolites and avoids derivatization steps common in fluorometric methods.[109][110] Sample preparation is critical across these techniques to prevent histamine degradation by endogenous enzymes like diamine oxidase or HNMT, often involving immediate homogenization in cold acid (0.1-0.4 M perchloric or trichloroacetic acid) to denature proteins and stabilize the amine, followed by centrifugation, filtration, or organic solvent extraction. For tissues, mechanical disruption or sonication in acid extracts histamine efficiently while minimizing artifactual release from mast cells.[111] A key limitation of these methods is histamine's short plasma half-life of 1-2 minutes due to rapid uptake and metabolism, necessitating immediate sample processing (within seconds to minutes) on ice and addition of preservatives like EDTA to inhibit further degradation during collection and storage. Often, stable metabolites such as N-methylhistamine are measured as proxies for histamine turnover.[112][113]Clinical and Research Assays