Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sexploitation film

View on WikipediaThe examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (January 2014) |

A sexploitation film (or sex-exploitation film) is a class of independently produced, low-budget[3] feature film that is generally associated with the 1960s[4] and early 1970s, and that serves largely as a vehicle for the exhibition of non-explicit sexual situations and gratuitous nudity. The genre is a subgenre of exploitation films. The term "sexploitation" has been used since the 1940s.[5][6]

In the United States, exploitation films were generally exhibited in urban grindhouse theatres, which were the precursors to the adult movie theaters of the 1970s and 1980s that featured hardcore pornography content. In Latin America (most notably in Argentina), exploitation and sexploitation films had meandering and complex relations with both moviegoers and government institutions: they were sometimes censored by democratic (but socially conservative) administrations and/or authoritarian dictatorships (especially during the 1970s and 80s),[7][8] and at other times they enjoyed an important success at the box office.

The term soft-core is often used to designate non-explicit sexploitation films after the general legalisation of hardcore content. Nudist films are often considered to be subgenres of the sex-exploitation genre as well. "Nudie" films and "Nudie-cuties" are associated genres.[4]

In the United States

[edit]

After a series of United States Supreme Court rulings in the late 1950s and 1960s, increasingly explicit sex films were distributed.[4] In 1957, Roth v. United States established that sex and obscenity were not synonymous.[4] The genre first emerged in the U.S. around 1960.[9]

There were initially three broad types: "nudie cuties" such as The Immoral Mr. Teas (1959), films set in nudist camps like Daughter of the Sun (1962) and somewhat more "artistic" foreign pictures, such as The Twilight Girls (1961).[3] Nudie cuties were popular in the early 1960s, and were a progression from the nudist camp films of the 1950s.[10] The Supreme Court had previously ruled that films set in nudist camps were exempt from the general ban on film nudity, as they were deemed to be educational.[10] In the early 1960s, films that purported to be documentaries and were thus "educational" enabled sexploitation producers to evade the censors.[11]

Nudie cuties were soon supplanted by "roughies," which commonly featured male violence against women, including kidnapping, rape and murder.[12][13] Lorna (1964) by Russ Meyer is widely considered to be the first roughie.[13] Herschell Gordon Lewis and David F. Friedman's Scum of the Earth! (1963) is another film that is cited as among the first in this genre.[14] Other notable roughie directors include Doris Wishman.[13]

In the United States, exploitation films initially played in grindhouse theatres,[15] as well as struggling independent theaters; however, by the end of the decade they were playing in established cinema chains.[3] As the genre developed during the 1960s films began showing scenes of simulated sex.[16] The films were opposed by religious groups and by the MPAA, which was concerned that sexploitation films were cutting into the profits of major film distributors.[17] Customers who attended screenings of sexploitation films were often characterised by the mainstream media as deviant, "dirty old men" and "raincoaters."[9]

In the mid-1960s some newspapers began banning advertisements for the films.[18] By the late 1960s the films were attracting a larger and broader audience, however, including couples rather than the single males who originally made up the vast majority of patrons.[17] The genre rapidly declined in the early 1970s due to advertising bans, the closure of many grindhouses and drive-in theaters and the growth of hardcore pornography in the "Golden Age of Porn."[15] Many theaters which had screened sexploitation films either switched to hardcore pornographic films or closed down.[19]

White coaters

[edit]In the late 1960s, American obscenity laws were tested by the Swedish film I Am Curious (Yellow).[4] After the 1969 ruling by the Supreme Court that the film was not obscene[20][21] because of its educational context,[22][23][24] the late 1960s and early 1970s saw a number of sexploitation films produced following this same format. These were widely referred to as "white coaters," because, in these films, a doctor dressed in a white coat would give an introduction to the graphic content that followed, qualifying the film as "educational." The ruling led to a surge in the production of sex films.[4] Language of Love and other Swedish and American films capitalised on this idea until the laws were relaxed.[25]

In Argentina

[edit]

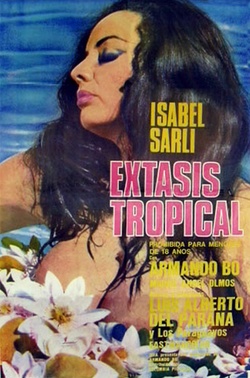

In the 1960s Argentine sexploitation films were made within a regular basis. The biggest national stars in that genre were Isabel Sarli and Libertad Leblanc. The genre rapidly declined during the 1980s, particularly with the advent of democracy in Argentina since 1983 onwards, and it disappeared completely in the 1990s, except for some low budget direct-to-video productions.

Although these movies were released in their home country, government censorship at the time (Argentina alternated between democracy and dictatorship for most of the 60s and 70s) was prone to -or had the steady habit of- heavily editing the films before their release, threatening with a full ban if the studio or the director did not comply. Armando Bó, who made several sexploitation and erotic films with his romantic partner and muse Isabel Sarli, is one of the most well-known cases in Argentina of having disputes with the censors who wanted to either put him in jail for making "obscene material" or ban his films, which were released mostly in a truncated form, and with many scenes excised from his movies at the time of their release.

One of the most notorious agents of government censorship during that period was Miguel Paulino Tato, who worked during de jure and de facto administrations as the director of the Argentine Ente de Calificación Cinematográfica (Film Rating Organization). In that capacity, Tato censored—banned or heavily edited—dozens of erotic or sexploitation films (from Argentina and from all over the world) during the 1960s and 1970s; he also banned or cut hundreds of domestic/international films of any kind and genre during the same era, always using the pretext of a righteous and moral fight against either "Marxism", "anti-catholic" or "subversive" movies who were, in his view, trying to "contaminate" the country's values and national identity. Although he exercised a mostly bureaucratic role, Tato was keen on giving interviews to the media describing his far-right authoritarian views and even boasting about being "a nazi" on several occasions. He was also a proud racist, and quite famously said on television, at the time of the Argentinian premiere of Shaft in Africa (1973): "Negros go back to Africa!" ("¡Negros, al Africa!").[26]

Rivalry between Isabel Sarli and Libertad Leblanc

[edit]

Libertad Leblanc's rivalry with Isabel Sarli – who was, and probably still is, the greatest sex symbol in Argentine cinema – was very conspicuous in the 1960s. They were the two greatest figures of erotic cinema in their home country, competing for the headlines as well as the box office success, and at the same time the contrast between the two, in appearance and in personality (on screen and off as well) couldn't be bigger: Isabel Sarli was a flashy brunette, with generous shapes and natural attributes. Libertad Leblanc was instead rather slim, reportedly had breast implants, dyed her hair platinum blonde, and maintained her distinctive white skin by constantly avoiding exposure to the sun. Sarli had a shy and somewhat innocent personality, and she always exuded a "homely and easy-going" public image; her movies were usually melodramas and comedies with a lot of nudity. In contrast, Leblanc was uninhibited and cunning, and gave a public image of a vamp or a seductress; she was dubbed as "The White Goddess" (La diosa blanca) by the media,[27] and her filmography includes police movies and thrillers.

"La Sarli", as they used to call her, was, as an actress, a product entirely created by Armando Bó, since the Argentine director was not only her longtime lover —Sarli and Bó were never legally married, but lived together as a couple until his death— but also her manager, her film producer and director, and even an authority figure, simultaneously. On the other hand, "La Leblanc", as they also used to call her, had a different background and was already used -from a young age, actually- to make her way on her own, and she was a true self-made woman of her time: she had disputes and argued as equals with producers, directors and distributors; she was her own manager and she co-produced almost all of her films -at a time when no woman did so-, as well as being almost always in charge of the distribution and promotion of her films. In this regard, a Mexican producer, with whom Leblanc made eight films, once told the media that "Libertad Leblanc, when talking about business, has a mustache".

In fact, it was Libertad Leblanc herself who installed the rivalry between her and Sarli in the media, as well as the popular conscience. In order to promote her first film, La Flor de Irupé (1962), Leblanc suggested a promotional poster with a black and white nude and a caption that read: "Libertad Leblanc, rival of Isabel Sarli". Although Isabel Sarli did not say anything at the time, Armando Bó, in a wrathful rapture, accused Leblanc of deviously using Sarli's international fame. Some time later, in a 2004 interview, Leblanc was sincere about the whole affair: “And [Bó] was right; but hey: we didn't spend a dime [on publicity] and everything came out perfectly"; in that same interview, when asked if she really believed there was a true rivalry between Sarli and her, Leblanc replied: "Not in any way. With Armando [Bó] we did have our run-ins because that fame [the publicity controversy] also circulated around the world. But she is divine; very naïve, yes, but she is a gorgeous woman...".[28]

Notable sexploitation directors

[edit]- Joe D'Amato

- Stephen C. Apostolof

- Armando Bó

- Tinto Brass

- Michael Findlay

- Jesús Franco

- David F. Friedman[4][12]

- Stanley Long

- George Harrison Marks

- Radley Metzger[29]

- Russ Meyer[30]

- Ted V. Mikels

- Andy Milligan

- Carl Monson

- Fred Olen Ray

- Jean Rollin

- Stephanie Rothman

- Joseph W. Sarno

- Andy Sidaris

- Emilio Vieyra

- Doris Wishman[31]

- Jim Wynorski

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Parish, James Robert; Stanke, Don E. (1975). The Glamour Girls. Arlington House. p. 463. ISBN 978-0870002441. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth; Zito, Stephen F. (1975). Sinema: American Pornographic Films and the People Who Make Them. New American Library. p. 66. ISBN 978-0275507701. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ a b c Sconce, p. 20

- ^ a b c d e f g Weitzer, Ronald John (2000). Sex for Sale: Prostitution, Pornography, and the Sex Industry. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 0-415-92295-X.

- ^ Clark, Randall (1995). At a Theater Or Drive-in Near You: The History, Culture, and Politics of the American Exploitation Film. Taylor & Francis. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-8153-1951-1. Retrieved September 11, 2025.

- ^ "sexploitation | Origin and meaning of sexploitation by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Fevrier, Andrés: Hollywood in Don Torcuato. The Adventures of Roger Corman and Héctor Olivera (2020, Argentina). "Hollywood en Don Torcuato. Las aventuras de Roger Corman y Héctor Olivera" is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license. 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- ^ Un Importante Preestreno (2015) Santiago Calori RaroVHS.com

- ^ a b Sconce, p. 19

- ^ a b Sconce, p. 49

- ^ Sconce, p. 60

- ^ a b Sconce, p.50

- ^ a b c Sconce, p. 52

- ^ "The Defilers/Scum of the Earth (1965/1963)". digitallyobsessed.com. February 25, 2001. Archived from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Sconce, p. 42

- ^ Sconce, p. 28

- ^ a b Sconce, p. 35

- ^ Sconce, p. 36

- ^ Piepenburg, Erik (June 2, 2016). "Sexploitation Films, Short on Good Taste, Still Have Devotees (Published 2016)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ "Byrne v. Karalexis, 396 U.S. 976 (1969)". Justia Law. Retrieved January 9, 2023. "Byrne v. Karalexis, 401 U.S. 216 (1971)". Justia Law. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ^ "Film International". filmint.nu. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ "'Barbara' Puts Emphasis on Sex". The New York Times. August 12, 1970. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ Newman, Frank (1968). Barbara. Traveller's Companion, Incorporated.

- ^ Gunn, Drewey Wayne (2016). Gay American novels, 1870–1970: a reader's guide. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7864-9905-2.

- ^ Harris, Will (August 31, 2005). "Harry Reems Interview: Harry Reems Lays It on the Table". Bullz-Eye.com.

- ^ "Miguel Tato, aquel increíble señor tijeras". La Nación (in Spanish). February 28, 1999. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ "Muere actriz argentina Libertad Leblanc". Ibercine (in Spanish). May 1, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ Dillon, Marta (January 23, 2004). "Siempre libre". Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ Sconce, p. 24

- ^ Sconce, p. 22

- ^ Sconce, p. 10

Sources

[edit]- Sconce, Jeffrey (2007). Sleaze Artists: Cinema at the Margins of Taste, Style, and Politics. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3964-9.

Further reading

[edit]- RE/Search No. 10: Incredibly Strange Films (RE/Search Publications, 1986) by V. Vale, Andrea Juno, ISBN 0-940642-09-3

- Immoral Tales: European Sex & Horror Movies 1956-1984 (1994) by Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs, ISBN 0-312-13519-X