Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Beta Lyrae

View on Wikipedia| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Lyra |

| Right ascension | 18h 50m 04.79525s[1] |

| Declination | +33° 21′ 45.6100″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 3.52[2] (3.25 – 4.36[3]) |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | B6-8II[4][5] + B[2] |

| U−B color index | −0.56[6] |

| B−V color index | +0.00[6] |

| Variable type | β Lyr[3] |

| Astrometry | |

| A | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −19.2[7] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 1.90[1] mas/yr Dec.: −3.53[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 3.39±0.17 mas[1] |

| Distance | 960 ± 50 ly (290 ± 10 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −3.82[8] |

| B | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −14±5[9] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 4.373±0.087[10] mas/yr Dec.: −0.982±0.098[10] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 3.0065±0.0542 mas[10] |

| Distance | 1,080 ± 20 ly (333 ± 6 pc) |

| Orbit[2] | |

| Primary | Aa1 |

| Companion | Beta Lyrae Aa2 |

| Period (P) | 12.9414 days |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 0.865±0.048 mas |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0 |

| Inclination (i) | 92.25 ± 0.82° |

| Longitude of the node (Ω) | 254.39 ± 0.83° |

| Details[11] | |

| β Lyr Aa1 | |

| Mass | 2.97 ± 0.2 M☉ |

| Radius | 15.2 ± 0.2 R☉ |

| Luminosity | 6,500 L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 2.5 ± 0.1 cgs |

| Temperature | 13,300 K |

| Age | 23 Myr |

| β Lyr Aa2 | |

| Mass | 13.16 ± 0.3 M☉ |

| Radius | 6.0 ± 0.2 R☉ |

| Luminosity | 26,300 L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.0 ± 0.1 cgs |

| Temperature | 30,000 ± 2,000 K |

| Other designations | |

| Sheliak, Shelyak, Shiliak, WDS 18501+3322[12] | |

| β Lyrae A: 10 Lyrae, AAVSO 1846+33, BD+33 3223, FK5 705, HD 174638, HIP 92420, HR 7106, SAO 67451/2 | |

| β Lyrae B: HD 174664, BD+33 3224, SAO 67453 | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | β Lyrae |

| B | |

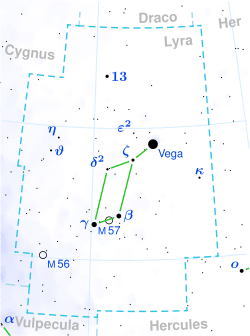

Beta Lyrae (β Lyrae, abbreviated Beta Lyr, β Lyr) officially named Sheliak (Arabic: الشلياق, Romanization: ash-Shiliyāq) (IPA: /ˈʃiːliæk/), the traditional name of the system, is a multiple star system in the constellation of Lyra. Based on parallax measurements obtained during the Hipparcos mission, it is approximately 960 light-years (290 parsecs) distant from the Sun.

Although it appears as a single point of light to the naked eye, it actually consists of six components of apparent magnitude 14.3 or brighter. The brightest component, designated Beta Lyrae A, is itself a triple star system, consisting of an eclipsing binary pair (Aa) and a single star (Ab). The binary pair's two components are designated Beta Lyrae Aa1 and Aa2. The additional five components, designated Beta Lyrae B, C, D, E, and F, are currently considered to be single stars.[12][13][14][15][16][17]

Nomenclature

[edit]β Lyrae (Latinised to Beta Lyrae) is the system's Bayer designation, established by Johann Bayer in his Uranometria of 1603, and denotes that it is the second brightest star in the Lyra constellation. WDS J18501+3322 is a designation in the Washington Double Star Catalog. The designations of the constituents as Beta Lyrae A, B and C, or alternatively WDS J18501+3322A, B and C, and additionally WDS J18501+3322D, E and F, and those of A's components - Aa1, Aa2 and Ab - derive from the convention used by the Washington Multiplicity Catalog (WMC) for multiple star systems, and adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).[18]

Beta Lyrae bore the traditional name Sheliak (occasionally Shelyak or Shiliak), derived from the Arabic الشلياق šiliyāq or Al Shilyāk, one of the names of the constellation of Lyra in Islamic astronomy.[19] Notably, in Arabic sources the Lyra constellation is primarily referred to as سِلْيَاق (Romanization: Siliyāq),[20][21] whereas شلياق (Šiliyāq) primarily is used to refer to Beta Lyrae in what might be a form of linguistic reborrowing.[22][23] Persian sources on the other hand, do refer to the Lyra constellation as شلياق (Šiliyāq), which may be the source of this confusion.[24][25]

In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[26] to catalogue and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN decided to attribute proper names to individual stars rather than entire multiple systems.[27] It approved the name Sheliak for the component Beta Lyrae Aa1 on 21 August 2016 and it is now so included in the List of IAU-approved Star Names.[28]

In Chinese astronomy, Tsan Tae (漸台 (Jiāntāi), meaning Clepsydra Terrace, refers to an asterism consisting of this star, Delta² Lyrae, Gamma Lyrae and Iota Lyrae.[29] Consequently, the Chinese name for Beta Lyrae itself is 漸台二 (Jiāntāièr, English: the Second Star of Clepsydra Terrace.)

Properties

[edit]Beta Lyrae Aa is a semidetached binary system made up of a stellar class B6-8 primary star and a secondary that is probably also a B-type star. The fainter, less massive star in the system was once the more massive member of the pair, which caused it to evolve away from the main sequence first and become a giant star. Because the pair are in a close orbit, as this star expanded into a giant it filled its Roche lobe and transferred most of its mass over to its companion.

The secondary, now more massive star is surrounded by an accretion disk from this mass transfer, with bipolar, jet-like features projecting perpendicular to the disk.[2] This accretion disk blocks humans' view of the secondary star, lowering its apparent luminosity and making it difficult for astronomers to pinpoint what its stellar type is. The amount of mass being transferred between the two stars is about 2 × 10−5 solar masses per year, or the equivalent of the Sun's mass every 50,000 years, which results in an increase in orbital period of about 19 seconds each year. The spectrum of Beta Lyrae shows emission lines produced by the accretion disc. The disc produces around 20% of the brightness of the system.[2]

In 2006, an adaptive optics survey detected a possible third companion, Beta Lyrae Ab. It was detected at 0.54" angular separation with a differential magnitude of +4.53. The difference in magnitudes suggests its spectral class is in the range B2-B5 V. This companion would make Beta Lyrae A a hierarchical triple system.[30]

Variability

[edit]

The variable luminosity of this system was discovered in 1784 by the British amateur astronomer John Goodricke.[32] In 1894, Aristarkh Belopolsky identified Beta Lyrae as an eclipsing spectroscopic binary.[33] The orbital plane of this system is nearly aligned with the line of sight from the Earth, so the two stars periodically eclipse each other. This causes Beta Lyrae to regularly change its apparent magnitude from +3.2 to +4.4 over an orbital period of 12.9414 days. It forms the prototype of a class of ellipsoidal "contact" eclipsing binaries.[3]

The two components are so close together that they cannot be resolved with optical telescopes, forming a spectroscopic binary. In 2008, the primary star and the accretion disk of the secondary star were resolved and imaged using the CHARA Array interferometer[34] and the Michigan InfraRed Combiner (MIRC)[35] in the near infrared H band (see video below), allowing the orbital elements to be computed for the first time.[2]

In addition to the regular eclipses, the system shows smaller and slower variations in brightness. These are thought to be caused by changes in the accretion disc and are accompanied by variation in the profile and strength of spectral lines, particularly the emission lines. The variations are not regular but have been characterised with a period of 282 days.[36]

The date of a primary minimum can be calculated according the following formula:

Primary_Minimum = 2436793.48 + 12.93095*n + 0.00000386*n*n

whereby n is a natural number. The calculated date is given in Julian days.

Companions

[edit]In addition to Beta Lyrae A, several other companions have been catalogued. β Lyr B, at an angular separation of 45.7", is of spectral type B7V, has an apparent magnitude of +7.2, and can easily be seen with binoculars. It is about 80 times as luminous as the Sun. In 1962 it was identified as spectroscopic binary with a period of 4.348 days,[37] but the 2004 release of the SB9 catalog of Spectroscopic Binary Orbits omitted it, so it is now considered a single star.[13]

The next two brightest components are E and F. β Lyr E is magnitude 10.1v, separation 67", and β Lyr F is magnitude 10.6v, separation 86". Both are chemically peculiar stars;[38] both are catalogued as Ap stars, although component F is sometimes thought to be an Am star.[39]

The Washington Double Star Catalog lists two fainter companions, C and D, at 47" and 64" separation, respectively.[40] Component C has been observed to vary in brightness by over a magnitude, but the type of variability is not known.[41]

Components A, B, and F are thought to be members of a group of stars around β Lyrae, at approximately the same distance and moving together. The others just happen to be in the same line of sight.[39] Analysis of Gaia Data Release 2 astrometry reveals a group of about 100 stars around β Lyrae which share its space motion and are at the same distance. This cluster has been named Gaia 8. The cluster members are all main sequence stars and the lack of a main sequence turnoff means that a precise age cannot be calculated, but the cluster age is estimated at 30 to 100 million years. The average Gaia DR2 parallax for the member stars is 3.4 mas.[4]

The Gaia spacecraft has provided these data for the stars listed in the WDS:

| Component[42] | Spectral Class | Magnitude (G) | Proper Motion | Radial Velocity (km/s) | Parallax (mas) | Simbad | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA (mas/yr) | δ (mas/yr) | ||||||

| A[43][a] | 3.25 – 4.36 | 2.045 ± 0.18 | -3.685 ± 0.2069 | 2.20 ± 0.7 | 3.5982 ± 0.1836 | [12] | |

| B[10] | B7V | 7.19 | 2.174 ± 0.09 | -1.272 ± 0.1039 | -14 ± 5 | 3.5125 ± 0.0898 | [13] |

| C[44] | B2 | 13.07 | -1.936 ± 0.01 | -1.934 ± 0.0129 | ? | 0.2884 ± 0.0104 | [14] |

| D[45] | K3V | 14.96 | 0.024 ± 0.034 | -17.781 ± 0.0409 | ? | 0.845 ± 0.0333 | [15] |

| E[46] | G5 | 9.77 | 1.841 ± 0.015 | 0.536 ± 0.0159 | 1.4 | 1.5737 ± 0.0155 | [16] |

| F[47] | G5 | 10.10 | 1.416 ± 0.013 | -3.963 ± 0.0149 | -16.83 ± 1.41 | 3.4897 ± 0.0133 | [17] |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007), "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 474 (2): 653–664, arXiv:0708.1752, Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357, S2CID 18759600.

- ^ a b c d e f Zhao, M.; et al. (September 2008), "First Resolved Images of the Eclipsing and Interacting Binary β Lyrae", The Astrophysical Journal, 684 (2): L95–L98, arXiv:0808.0932, Bibcode:2008ApJ...684L..95Z, doi:10.1086/592146, S2CID 17510817.

- ^ a b c Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; et al. (2009). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+ 2007-2013)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/GCVS. Originally Published in: 2009yCat....102025S. 1. Bibcode:2009yCat....102025S.

- ^ a b c Bastian, U. (2019). "Gaia 8: Discovery of a star cluster containing β Lyrae". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 630: L8. arXiv:1909.04612. Bibcode:2019A&A...630L...8B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201936595.

- ^ Mourard, D.; et al. (2018). "Physical properties of β Lyrae a and its opaque accretion disk". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 618: A112. arXiv:1807.04789. Bibcode:2018A&A...618A.112M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201832952. S2CID 73647379.

- ^ a b Nicolet, B. (1978), "Photoelectric photometric Catalogue of homogeneous measurements in the UBV System", Observatory, Bibcode:1978ppch.book.....N.

- ^ Wilson, Ralph Elmer (1953), "General catalogue of stellar radial velocities", Washington: 0, Bibcode:1953GCRV..C......0W.

- ^ Anderson, E.; Francis, Ch. (2012), "XHIP: An extended hipparcos compilation", Astronomy Letters, 38 (5): 331, arXiv:1108.4971, Bibcode:2012AstL...38..331A, doi:10.1134/S1063773712050015, S2CID 119257644.

- ^ Evans, D. S. (1967). "The Revision of the General Catalogue of Radial Velocities". Determination of Radial Velocities and Their Applications. 30: 57. Bibcode:1967IAUS...30...57E.

- ^ a b c d Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. A1. arXiv:1804.09365. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ Mennickent, R. E.; et al. (2006), "On the accretion disc and evolutionary stage of β Lyrae", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 432 (1): 799–809, arXiv:1303.5812, Bibcode:2013MNRAS.432..799M, doi:10.1093/mnras/stt515, S2CID 119100891.

- ^ a b c "bet Lyr -- Eclipsing binary of beta Lyr type", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ a b c "bet Lyr B -- Star", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ a b "bet Lyr C -- Star", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ a b "UCAC3 247-141831 -- Star", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ a b "BD+33 3222 -- Star", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ a b "BD+33 3225 -- Star", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ Hessman, F. V.; Dhillon, V. S.; Winget, D. E.; Schreiber, M. R.; Horne, K.; Marsh, T. R.; Guenther, E.; Schwope, A.; Heber, U. (2010). "On the naming convention used for multiple star systems and extrasolar planets". arXiv:1012.0707 [astro-ph.SR].

- ^ Allen, Richard Hinckley (1899), "Star-names and their meanings", New York: 287, Bibcode:1899sntm.book.....A.

- ^ Ghaleb, Edouard (1988). الموسوعة في علوم الطبيعة ، المجلد الثنين [Encyclopedia of Natural Sciences, vol. 2] (in Arabic) (2nd ed.). Lebanon: Dar El-Mashriq Publications. p. 806. ISBN 2-7214-2148-4.

- ^ "Al Moqatel - الظواهر الطبيعية في القرآن والسُّنة، النجوم". www.moqatel.com. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ "الكوكبات: كوكبة القيثارة" [The Lyra Constellation]. www.startimes.com. 19 August 2008. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ "النجوم الثنائية" [Binary Stars]. saaa-sy.yoo7.com (in Arabic). Syrian Astronomical Association. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ آزادگان, علی (2006-10-11). "صورتهاي فلكي فصل تابستان" [Summer Constellations] (in Persian). Archived from the original on 2014-02-04. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ "معرفی و رصد صورت فلکی شلیاق و ستاره ی نسرواقع" [Introducing and observing a loose constellation and a real star.]. موسسه علمی پژوهشی نجم شمال (in Persian). North Star Scientific Research Institute. Archived from the original on 2024-01-29. Retrieved 2024-01-29.

- ^ IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN), International Astronomical Union, archived from the original on 10 June 2016, retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "WG Triennial Report (2015-2018) - Star Names" (PDF). p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-23. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Naming Stars". IAU.org. Archived from the original on 10 March 2025. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ^ (in Chinese) AEEA (Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy) 天文教育資訊網 2006 年 7 月 3 日 Archived 2011-05-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Roberts, Lewis C. Jr.; Turner, Nils H.; ten Brummelaar, Theo A. (2006). "Adaptive Optics Photometry and Astrometry of Binary Stars. II A Multiplicity Survey of B Stars". The Astronomical Journal. 133 (2): 545–552. Bibcode:2007AJ....133..545R. doi:10.1086/510335.

- ^ "MAST: Barbara A. Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes". Space Telescope Science Institute. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Hoskin, M. (1979), "Goodricke, Pigott and the Quest for Variable Stars", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 10 (1): 23–41, Bibcode:1979JHA....10...23H, doi:10.1177/002182867901000103, S2CID 118155505.

- ^ Walter, S. (2023), "The Poincaré pear and Poincaré-Darwin fission theory in astrophysics, 1885-1901", Philosophia Scientiae, 27 (3): 159–187, arXiv:2311.02054, Bibcode:2023arXiv231102054W, doi:10.4000/philosophiascientiae.4178, S2CID 264388277.

- ^ ten Brummelaar, Theo; et al. (July 2005), "First Results from the CHARA Array. II A Description of the Instrument", The Astrophysical Journal, 628 (453): 453–465, arXiv:astro-ph/0504082, Bibcode:2005ApJ...628..453T, doi:10.1086/430729, S2CID 987223.

- ^ Monnier, John D.; et al. (2006). "Michigan Infrared Combiner (MIRC): Commissioning results at the CHARA Array". In Monnier, John D.; Schöller, Markus; Danchi, William C. (eds.). Advances in Stellar Interferometry (PDF). SPIE Proceedings. Vol. 6268. pp. 62681P. Bibcode:2006SPIE.6268E..1PM. doi:10.1117/12.671982. S2CID 21920992.

- ^ Carrier, F.; Burki, G.; Burnet, M. (2002). "Search for duplicity in periodic variable Be stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 385 (2): 488. Bibcode:2002A&A...385..488C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020174.

- ^ Abt, Helmut A.; Jeffers, Hamilton M.; Gibson, James; Sandage, Allan R. (September 20, 1961). "The Visual Multiple System Containing Beta Lyrae". The Astrophysical Journal. 135: 429. Bibcode:1962ApJ...135..429A. doi:10.1086/147282.

- ^ Skiff, B. A. (2014). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Spectral Classifications (Skiff, 2009-2016)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog. Bibcode:2014yCat....1.2023S.

- ^ a b Abt, H. A.; Levy, S. G. (1976). "Visual multiples. III. ADS 11745 (beta Lyrae group)". The Astronomical Journal. 81: 659. Bibcode:1976AJ.....81..659A. doi:10.1086/111936.

- ^ Mason, Brian D.; Wycoff, Gary L.; Hartkopf, William I.; Douglass, Geoffrey G.; Worley, Charles E. (2001). "The 2001 US Naval Observatory Double Star CD-ROM. I. The Washington Double Star Catalog". The Astronomical Journal. 122 (6): 3466. Bibcode:2001AJ....122.3466M. doi:10.1086/323920.

- ^ Proust, D.; Ochsenbein, F.; Pettersen, B. R. (1981). "A catalogue of variable-visual binary stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series. 44: 179. Bibcode:1981A&AS...44..179P.

- ^ "ADS 11745". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg.

- ^ Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. A1. arXiv:1804.09365. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. A1. arXiv:1804.09365. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. A1. arXiv:1804.09365. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. A1. arXiv:1804.09365. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. A1. arXiv:1804.09365. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

External links

[edit]- Kaler, James B. (2002), The hundred greatest stars, Copernicus Series, Springer, p. 29, ISBN 978-0-387-95436-3

- Philippe Stee's homepage: Hot and Active Stars Research

- Kaler, James B., "SHELIAK (Beta Lyrae)", Stars, University of Illinois, retrieved 2011-12-20

- Bruton, Dan; Linenschmidt, Robb; Schmude, Jr., Richard W., Watching Beta Lyrae Evolve, Texas A&M University, archived from the original on 2003-02-25, retrieved 2011-12-20

- Beck, Sara J. (July 1, 2011), Beta Lyrae, AAVSO, retrieved 2011-12-20

Beta Lyrae

View on GrokipediaNomenclature

Traditional Names

Beta Lyrae was assigned its Bayer designation, β Lyrae, by the German astronomer Johann Bayer in his 1603 star atlas Uranometria, which systematically labeled stars in each constellation using Greek letters in order of apparent brightness.[7] The star's primary traditional name, Sheliak (sometimes spelled Shelyak or Shiliak), derives from the Arabic term al-shilyāk (or similar transliterations), one of the names for the constellation Lyra as a whole in medieval Arabic astronomy; it is translated as "the tortoise" in some sources (likely alluding to the mythological tortoise whose shell Hermes used to fashion the lyre) and "the harp" in others, reflecting the constellation's lyre shape.[3][8] In Persian astronomy, the star was known as Šiliak, a direct adaptation of the Arabic name.[9] In ancient Chinese astronomy, Beta Lyrae formed part of the asterism Jiāntāi (漸台, "Clepsydra Terrace"), specifically designated as Jiāntāièr (漸台二, "Second Star of Clepsydra Terrace"), within the larger celestial palace enclosure.[2][10] The International Astronomical Union (IAU) formally approved Sheliak as the proper name for the system's primary component, Beta Lyrae Aa1, on August 21, 2016, through its Working Group on Star Names.[3] Historically, the name Sheliak has been used for the integrated system comprising multiple components.Astronomical Designations

Beta Lyrae is formally designated HD 174638 in the Henry Draper Catalogue, a comprehensive survey of stellar spectra and magnitudes conducted in the early 20th century.[11] In the Hipparcos Catalogue, which provided precise astrometric data from the 1990s satellite mission, it is listed as HIP 92420.[12] The Gaia Data Release 3, from the European Space Agency's astrometry mission, assigns the primary component the identifier Gaia DR3 2090687795056051328, enabling high-precision position, parallax, and proper motion measurements.[13] The multiple-star system follows a hierarchical naming convention, with the brightest member labeled Beta Lyrae A, comprising the close eclipsing binary pair Aa and the nearby third star Ab.[14] Surrounding this core are fainter outer companions designated B through F, resolved as visual multiples.[15] In the Washington Double Star Catalog (WDS), maintained by the U.S. Naval Observatory, the system is cataloged as WDS J18501+3322, compiling historical and modern measurements of double and multiple stars.[16] The primary visual pair AB, discovered by F. G. W. Struve and designated STFA 39, has a typical separation of about 45.7 arcseconds, while other pairs like BC and CD exhibit separations ranging from 40 to 100 arcseconds based on epoch-dependent observations.[17] For cross-referencing across databases, the SIMBAD astronomical database at the Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg (CDS) uses the primary identifier * bet Lyr, linking to numerous catalogs including HD, HIP, Gaia, and WDS entries.[18] The CDS's VizieR service provides further identifiers and metadata for comprehensive queries on the system's components.[19] The traditional name Sheliak serves as a common alias in these references.Observational History

Early Discoveries

Beta Lyrae, a prominent star in the constellation Lyra, was cataloged in ancient Greek astronomy as part of the lyre-shaped figure associated with the musician Orpheus. It appears in Ptolemy's Almagest (2nd century CE), the foundational Greek star catalog, where Lyra includes 16 stars, with Beta Lyrae noted as the second-brightest after Alpha Lyrae (Vega).[8] Arabic astronomers, building on Ptolemaic traditions during the Islamic Golden Age, referred to the star as Sheliak, derived from al-Shilyāk, a term evoking a tortoise shell or harp-like form linked to the constellation's musical theme; this name reflects observations in catalogs like those of Al-Sufi (10th century). In ancient Chinese astronomy, Beta Lyrae was known as Tsan Tae within the Tianfu asterism, part of broader stellar records dating back to the Han dynasty (circa 2nd century BCE), emphasizing its role in seasonal and calendrical systems.[2] The star's variability was first recognized in 1784 by English amateur astronomer Edward Pigott, who observed irregular brightness changes during systematic sky surveys from his York observatory.[20] Pigott's discovery was soon confirmed by his collaborator John Goodricke, a young deaf astronomer who meticulously tracked the light curve over several months, estimating an initial period of about 13 days (precisely 12 days 21 hours 41 minutes in his 1785 report).[21] Goodricke hypothesized that the variations resulted from eclipses or occultations by a companion body, marking an early insight into binary star dynamics, though the exact mechanism remained debated.[22] Advancing into the 19th century, spectroscopic observations by Italian astronomer Angelo Secchi in 1866 revealed Beta Lyrae's spectrum as belonging to his Class III (now recognized as B-type stars), characterized by strong Balmer hydrogen emission lines superimposed on absorption features—a pioneering identification of what would later be termed Be stars.[23] Secchi's work at the Vatican Observatory, using a simple slit spectroscope, highlighted the star's hot, blue-white nature and unusual spectral variability tied to its light changes.[24] In the 1880s, Harvard astronomer Edward C. Pickering advanced the binary hypothesis through detailed spectral analysis, noting cyclic shifts in emission lines that suggested orbital motion between two massive components, challenging earlier single-star pulsation models.[25] The eclipsing binary nature of Beta Lyrae received formal recognition in 1907 by German astronomer Hans Ludendorff, who analyzed light curves and radial velocity data to confirm mutual eclipses as the cause of the observed variations, establishing it as a prototype for semi-detached binary systems.[26] Beta Lyrae thus became the namesake for the Beta Lyrae variable class, characterized by continuous light modulation from close-contact eclipses.Recent Interferometric and Spectroscopic Studies

In the mid-20th century, radial velocity observations played a pivotal role in elucidating the dynamics of Beta Lyrae. Studies by Sahade and collaborators in the 1950s, including detailed spectroscopic analysis of emission and absorption lines, provided evidence for ongoing mass transfer between the binary components, marking one of the earliest confirmations of this process in close binaries.[27] These measurements revealed asymmetric velocity curves indicative of material flow from the donor to the accretor, with semi-amplitudes supporting a mass ratio consistent with semidetached evolution. Ultraviolet spectroscopy advanced this understanding during the 1970s and 1980s through observations with the International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE) satellite. IUE spectra captured strong emission lines and continuum flux variations, attributed to hot spots where the mass-transfer stream impacts the accretion disk, heating regions to temperatures exceeding 10,000 K.[28] These data highlighted phase-dependent emissions, particularly during non-eclipse phases, revealing the disk's opaque nature and the presence of extended gaseous structures illuminated by the central stars.[29] Post-2000 interferometric efforts have resolved fine-scale structures in the system. Observations with the CHARA Array in 2018 resolved the radius of the secondary gainer component at approximately 6 solar radii and mapped the extent of the optically thick accretion disk, spanning up to 30 solar radii, through near-infrared interferometry combining VEGA and MIRC instruments.[30] This work confirmed the disk's flattened geometry and its dominance in the system's visibility function, providing constraints on the mass-transfer rate. Space-based astrometry and photometry have further refined systemic parameters. The Gaia Data Release 3 (2022) parallax measurement of 3.01 ± 0.05 mas yields a distance of approximately 1080 light years (332 parsecs), refining prior Hipparcos estimates and aiding in absolute luminosity determinations. Meanwhile, Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) photometry since 2018 has delivered high-cadence light curves spanning multiple orbits, confirming the orbital period's stability at 12.9414 days with no significant deviations over short baselines.[31] Recent analyses (as of 2023) of archival light curves have further confirmed the orbital period's long-term stability at 12.9414 days, supporting models of steady mass transfer.[32] The star cluster Gaia 8, centered on Beta Lyrae with ~100 members, was discovered in 2019 using Gaia DR2 and further confirmed by Gaia DR3 (2022) data, providing evidence of co-moving companions.[33] Additionally, there is an ongoing need for infrared spectroscopy with the James Webb Space Telescope to probe the cooler outer components (B–F) and disentangle their contributions from the inner system's glare.Physical Properties

Position and Distance

Beta Lyrae is located in the constellation Lyra, positioned near the bright star Vega. Its equatorial coordinates for the epoch J2000.0 are right ascension 18h 50m 04.63s and declination +33° 21′ 45.8″.[34] The system has a proper motion of +1.90 mas/yr in right ascension and -3.53 mas/yr in declination, as determined from Gaia Data Release 3 observations.[35] The distance to Beta Lyrae is 960 ± 50 light-years (290 ± 10 pc), derived from the Gaia DR3 parallax measurement of 3.40 ± 0.17 mas; this value revises earlier estimates from the Hipparcos mission, which suggested a similar distance.[36][35] The systemic radial velocity of the Beta Lyrae system is -18.1 ± 0.5 km/s.[30] The system is visible from most locations in the northern hemisphere, reaching a maximum apparent magnitude of 3.4.Integrated System Characteristics

The Beta Lyrae system exhibits a mean apparent visual magnitude of 3.52 in the V band, varying between 3.4 and 4.3 due to its eclipsing nature.[2] Its absolute visual magnitude is approximately -3.0, reflecting the combined luminosity of the dominant inner components at a distance of about 290 pc as measured by Gaia.[37] The integrated spectral type of the system is classified as B8Ib, arising predominantly from the spectral contributions of the A subsystem's evolved supergiant and its companion.[30] The age of the Beta Lyrae system is estimated at 30–100 million years, consistent with evolutionary models of its massive binary components and supported by its membership in the young open cluster Gaia 8, which shares similar proper motions, parallax, and radial velocity.[33] The system's metallicity is solar-like, with overall chemical abundances approximating those of the Sun, though evidence from spectroscopic analysis indicates past enrichment due to mass transfer, including significant helium overabundance (up to 6 times solar) in the atmosphere of the primary component.[30]Variability

Eclipsing Binary Behavior

Beta Lyrae serves as the prototype for the Beta Lyrae variable class of eclipsing binaries, featuring short-period photometric variations driven by mutual eclipses in its inner Aa subsystem. The orbital period of this subsystem is precisely measured at 12.94129 ± 0.00007 days, reflecting the close interaction between the components.[38] This period governs the timing of the eclipses, with the equation for the orbital cycle given by days. Interferometric measurements have further constrained the semi-major axis of the relative orbit to approximately 58 R_, highlighting the compact nature of the system.[30] The light curve displays continuous variability outside of eclipse phases, arising from tidal distortion of the stellar envelopes and active mass transfer from the donor to the gainer star. These effects produce a smoothly undulating profile, with the stars' ellipsoidal shapes contributing to the overall flux modulation. The eclipses feature broad minima without flat bottoms, resulting from the extended sizes of the stars, the accretion disk, and high orbital inclination near 90 degrees.[2] The primary eclipse occurs when the cooler primary component (Aa1) is occulted by the hotter secondary (Aa2), reaching a depth of about 1.0 magnitude in visual bands and lasting roughly 1.5 days due to the extended duration of the alignment. In contrast, the secondary eclipse, where Aa2 is occulted by Aa1, is significantly shallower at 0.1 magnitude, primarily because of the asymmetric distribution of the optically thick accretion disk that partially obscures the cooler star and alters the effective eclipsing geometry.[10] This asymmetry in eclipse depths underscores the role of the disk in shaping the observed photometry, distinguishing Beta Lyrae from simpler detached eclipsing systems.[30]Long-Term Photometric Variations

The orbital period of Beta Lyrae is increasing at a rate of about 19 seconds per year, attributed to ongoing mass transfer from the primary to the secondary, which lengthens the orbit over time.[2] This secular change is monitored through timing of eclipses and contributes to the system's long-term evolution. Beta Lyrae displays long-term photometric variations superimposed on its short-term eclipsing behavior, characterized by a prominent 282-day cycle identified through extensive V-band monitoring. This periodicity was established from 2852 homogenized observations spanning 36 years, revealing a cyclic modulation in brightness that affects the overall light curve shape.[39] The cycle has an amplitude of approximately Δm ≈ 0.15 mag over the ~282 days, influencing eclipse depths and out-of-eclipse brightness levels.[40] The origin of the 282-day period remains debated but has been attributed to precession of the accretion disk or orbital apsidal motion in the inner binary system. Early models suggested disk precession could modulate the disk's orientation and visibility, leading to periodic flux changes, while apsidal motion might alter the geometry of mass transfer.[41] However, detailed analyses indicate that neither mechanism fully explains the observed stability and amplitude, with alternative explanations involving variable mass transfer rates that thicken or thin the disk over super-orbital timescales.[40] Beyond this cycle, Beta Lyrae exhibits irregular photometric fluctuations of 0.1–0.2 mag occurring over several years, indicative of instabilities in the accretion disk structure. These variations arise from episodic changes in mass transfer or disk viscosity, causing non-periodic brightenings and fadings that disrupt the regularity of the 282-day modulation. Ground-based surveys, including data from the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN) collected throughout the 2010s, document these fluctuations without evidence of strict periodicity, highlighting the dynamic nature of the disk.[42] Recent space-based observations, such as those from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) after 2020, provide high-cadence photometry but lack comprehensive analysis of cycle stability for these long-term variations. This gap limits current understanding of whether the 282-day period remains consistent or evolves amid the irregular fluctuations.[31]Stellar Components

The Inner Triple System (Beta Lyrae A)

The inner triple system of Beta Lyrae A consists of a close eclipsing binary (Aa1 and Aa2) and a more distant companion (Ab), forming a hierarchical configuration with ongoing mass transfer in the inner pair. The donor star Aa1 is a semi-detached B6-8II giant undergoing Roche lobe overflow, transferring material to the accretor Aa2 via an opaque accretion disk. This mass transfer has reversed the initial mass ratio, placing the system in a post-main-sequence evolutionary stage where the donor has expanded beyond its Roche lobe, leading to a current mass ratio q ≈ 0.23 (defined as MAa1 / MAa2). The Roche lobe geometry is highly distorted due to the close orbit and rapid rotation of Aa1, with the donor filling approximately 100% of its Roche lobe volume. The donor Aa1 has a mass of 2.97 ± 0.06 M⊙, a radius of 15.2 ± 0.2 R⊙, and an effective temperature Teff = 13,300 K, consistent with its spectral classification and photometric properties during non-eclipsing phases.[3] The accretor Aa2 is a B-type star embedded in an opaque accretion disk, with a mass of 13.16 ± 0.08 M⊙ (yielding a total binary mass of 16.13 M⊙), an effective temperature Teff ≈ 30,000 K for the central star, and a disk radius of ~20 R⊙. The disk is optically thick, contributing significantly to the system's luminosity and the observed variability from Aa eclipses, where the disk partially occults the donor during secondary eclipse. The mass transfer rate is estimated at ~10−5 M⊙ yr−1, sustaining the disk structure and jet-like outflows observed in high-resolution imaging.[43] The third component Ab is a B2-B5 V main-sequence star with an estimated mass of ~3–5 M⊙, orbiting the inner binary at an angular separation of 0.25″ (corresponding to ~85 AU at the system's distance of ~340 pc) with an orbital period of ~200 years. Ab was detected via adaptive optics imaging in 2006–2008, revealing its bound orbit and contribution to the system's dynamics without significant interaction with the inner mass transfer.[43] The triple system's stability is maintained by the wide separation of Ab, which has minimal influence on the inner binary's evolution but may affect long-term photometric variations through gravitational perturbations.Outer Companions (Beta Lyrae B–F)

The Beta Lyrae system features several fainter outer companions designated B through F, located at angular separations ranging from tens to hundreds of arcseconds from the dominant inner triple system (Beta Lyrae A), which accounts for the vast majority of the system's integrated brightness. These companions were first cataloged as part of the visual multiple ADS 11745 in early astrometric surveys, with subsequent spectroscopic and photometric studies aiming to assess their physical association through proper motions, radial velocities, and distances.[44] While Beta Lyrae A lies at a distance of approximately 340 pc based on Gaia DR3 parallax measurements, the binding status of the outer stars remains debated, with some showing consistent kinematics and others appearing unbound; potential membership in the Gaia 8 open cluster (discovered 2019, ~100 members centered on Beta Lyrae) supports association for kinematically matched components like B and F.[45] No resolved orbital parameters for these wide companions have been determined since 2019, limiting insights into their long-term dynamics.[33] Beta Lyrae B is the brightest outer companion, classified as a B7 V main-sequence star with an apparent visual magnitude of 7.2. It is separated by about 46 arcseconds from Beta Lyrae A and exhibits a radial velocity of -18.3 km/s, closely matching that of the inner system (-17.5 to -19.5 km/s), supporting potential physical association and possible Gaia 8 membership.[46] However, pre-Gaia estimates placed it at around 1,080 light-years, suggesting it could be a foreground interloper, though recent Gaia DR3 data yield a parallax corresponding to roughly 350 pc, indicating similar distance and likely membership in the Gaia 8 cluster.[44][47] At a separation of 47 arcseconds, Beta Lyrae C is a B2 spectral type star with an apparent magnitude of 13.07 and evidence of photometric variability, though its type remains unspecified.[48] It shows possible common proper motion with the inner system in older measures, but Gaia DR3 astrometry reveals a significantly larger distance of over 3,400 pc and differing proper motions (pmRA = -1.859 mas/yr, pmDEC = -1.934 mas/yr compared to the inner system's +2.045 mas/yr, -3.685 mas/yr), implying it is unbound and likely a chance alignment.[48] Its membership in the Gaia 8 cluster centered on Beta Lyrae remains unclear due to these discrepancies.[33] Beta Lyrae D, a faint K3 V red dwarf with an apparent magnitude of 14.96, orbits at 86 arcseconds from the primary. Limited spectroscopic data confirm its late-type nature, and photometric analysis suggests it is a background object not physically linked to Beta Lyrae, with no evidence of shared motion or cluster association.[44] The companions E and F form a close pair at separations of 45 and 47 arcseconds from Beta Lyrae A, respectively, with magnitudes of 10.1 and 10.6. Both are classified as G5 stars with chemical peculiarities suggestive of Am-type metallic-line anomalies, though E's classification carries uncertainty (possibly Am).[46] Radial velocity measurements for E (+10.9 km/s) disagree with the inner system's values, indicating it is probably unbound, while F's kinematics are more consistent, hinting at possible association and Gaia 8 membership.[46] Like C and D, their membership in the Gaia 8 cluster is unresolved, with no post-2019 orbital resolutions available.[33]| Component | Spectral Type | Apparent Magnitude (V) | Separation (arcsec) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | B7 V | 7.2 | ~46 | Possible bound member; radial velocity match; likely Gaia 8.[46] |

| C | B2 | 13.07 | 47 | Variable; likely unbound (distant per Gaia).[48] |

| D | K3 V | 14.96 | 86 | Faint red dwarf; background object.[44] |

| E | G5 (Am?) | 10.1 | 45 | Chemically peculiar; likely unbound.[46] |

| F | G5/Am | 10.6 | 47 | Chemically peculiar; paired with E, possible bound, Gaia 8.[46] |