Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Orpheus

View on Wikipedia| Orpheus | |

|---|---|

Orpheus, wearing a Phrygian cap, is surrounded by animals, who are charmed by his lyre-playing. Roman Orpheus mosaic from Palermo, 2nd century AD[1] | |

| Abode | Pimpleia, Pieria |

| Symbol | Lyre |

| Genealogy | |

| Born | |

| Died | |

| Parents | Oeagrus and Calliope |

| Spouse | Eurydice |

| Children | Musaeus |

In Greek mythology, Orpheus (/ˈɔːrfiːəs, ˈɔːrfjuːs/ ⓘ; Ancient Greek: Ὀρφεύς, classical pronunciation: [or.pʰeú̯s]) was a bard,[2][3][4][5] legendary musician and prophet. He was also a renowned poet and, according to legend, travelled with Jason and the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece,[6] and descended into the underworld to recover his lost wife, Eurydice.[7]

The major stories about him are centered on his ability to charm all living things and even stones with his music (the usual scene in Orpheus mosaics), his attempt to retrieve his wife Eurydice from the underworld, and his death at the hands of the maenads of Dionysus, who got tired of his mourning for his late wife Eurydice. As an archetype of the inspired singer, Orpheus is one of the most significant figures in the reception of classical mythology in Western culture, portrayed or alluded to in countless forms of art and popular culture including poetry, film, opera, music, and painting.[8]

For the Greeks, Orpheus was a founder and prophet of the so-called "Orphic" mysteries.[9] He was credited with the composition of a number of works, among which are a number of now-lost theogonies, including the theogony commented upon in the Derveni papyrus,[10] as well as extant works such the Orphic Hymns, the Orphic Argonautica, and the Lithica.[11] Shrines containing purported relics of Orpheus were regarded as oracles.[12]

Etymology

[edit]Several etymologies for the name Orpheus have been proposed. A probable suggestion is that it is derived from a hypothetical PIE root *h₃órbʰos 'orphan, servant, slave' and ultimately the verb root *h₃erbʰ- 'to change allegiance, status, ownership'.[13] Cognates could include Ancient Greek: ὄρφνη (órphnē; 'darkness')[14] and ὀρφανός (orphanós; 'fatherless, orphan')[15] from which comes English 'orphan' by way of Latin.

Fulgentius, a mythographer of the late 5th to early 6th century AD, gave the unlikely etymology meaning "best voice", "Oraia-phonos".[16]

Background

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Greek mythology |

|---|

|

| Deities |

| Heroes and heroism |

| Related |

|

Ancient Greece portal Myths portal |

Although Aristotle did not believe that Orpheus existed, all other ancient writers believed he once was a real person, though living in remote antiquity. Most of them believed that he lived several generations before Homer.[17] The earliest literary reference to Orpheus is a two-word fragment of the 6th-century BC lyric poet Ibycus: onomaklyton Orphēn ('Orpheus famous-of-name'). He is not mentioned by Homer or Hesiod.[18] Most ancient sources accept his historical existence; Aristotle is an exception.[19][20] Pindar calls Orpheus 'the father of songs'[21] and identifies him as a son of the Thracian mythological king Oeagrus[22] and the Muse Calliope.[23]

Greeks of the Classical age venerated Orpheus as the greatest of all poets and musicians; it was said that while Hermes had invented the lyre, Orpheus perfected it. Poets such as Simonides of Ceos said that Orpheus' music and singing could charm the birds, fish and wild beasts, coax the trees and rocks into dance,[24] and divert the course of rivers.

Orpheus was one of the handful of Greek heroes[25] to visit the underworld and return; his music and song had power even over Hades. The earliest known reference to this descent to the underworld is the painting by Polygnotus (5th century BCE) described by Pausanias (2nd century CE), where no mention is made of Eurydice. Euripides and Plato both refer to the story of his descent to recover his wife, but do not mention her name; a contemporary relief (about 400 BC) shows Orpheus and his wife with Hermes. The elegiac poet Hermesianax called her Agriope; and the first mention of her name in literature is in the Lament for Bion (1st century BC).[17]

Some sources credit Orpheus with further gifts to humankind: medicine, which is more usually under the auspices of Asclepius (Aesculapius) or Apollo; writing,[26] which is usually credited to Cadmus; and agriculture, where Orpheus assumes the Eleusinian role of Triptolemus as giver of Demeter's knowledge to humankind. Orpheus was an augur and seer; he practiced magical arts and astrology, founded cults to Apollo and Dionysus,[27] and prescribed the mystery rites preserved in Orphic texts. Pindar and Apollonius of Rhodes[28] place Orpheus as the harpist and companion of Jason and the Argonauts. Orpheus had a brother named Linus, who went to Thebes and became a Theban.[29] He is claimed by Aristophanes and Horace to have taught cannibals to subsist on fruit, and to have made lions and tigers obedient to him. Horace believed, however, that Orpheus had only introduced order and civilization to savages.[30]

Strabo (64 BC – c. AD 24) presents Orpheus as a mortal, who lived and died in a village close to Olympus.[31] "Some, of course, received him willingly, but others, since they suspected a plot and violence, combined against him and killed him." He made money as a musician and "wizard" – Strabo uses αγυρτεύοντα (agurteúonta),[32] also used by Sophocles in Oedipus Tyrannus to characterize Tiresias as a trickster with an excessive desire for possessions. Αγύρτης (agúrtēs) most often meant 'charlatan'[33] and always had a negative connotation. Pausanias writes of an unnamed Egyptian who considered Orpheus a μάγευσε (mágeuse), i.e., magician.[34][non-primary source needed]

"Orpheus ... is repeatedly referred to by Euripides, in whom we find the first allusion to the connection of Orpheus with Dionysus and the infernal regions: he speaks of him as related to the Muses (Rhesus 944, 946); mentions the power of his song over rocks, trees, and wild beasts (Medea 543, Iphigenia in Aulis 1211, Bacchae 561, and a jocular allusion in Cyclops 646); refers to his charming the infernal powers (Alcestis 357); connects him with Bacchanalian orgies (Hippolytus 953); ascribes to him the origin of sacred mysteries (Rhesus 943), and places the scene of his activity among the forests of Olympus (Bacchae 561.)"[35] "Euripides [also] brought Orpheus into his play Hypsipyle, which dealt with the Lemnian episode of the Argonautic voyage; Orpheus there acts as coxswain, and later as guardian in Thrace of Jason's children by Hypsipyle."[17]

"He is mentioned once only, but in an important passage, by Aristophanes (Frogs 1032), who enumerates, as the oldest poets, Orpheus, Musaeus, Hesiod, and Homer, and makes Orpheus the teacher of religious initiations and of abstinence from murder ..."[35]

"Plato (Apology, Protagoras), ... frequently refers to Orpheus, his followers, and his works. He calls him the son of Oeagrus (Symposium), mentions him as a musician and inventor (Ion and Laws bk 3.), refers to the miraculous power of his lyre (Protagoras), and gives a singular version of the story of his descent into Hades: the gods, he says, imposed upon the poet, by showing him only a phantasm of his lost wife, because he had not the courage to die, like Alcestis, but contrived to enter Hades alive, and, as a further punishment for his cowardice, he met his death at the hands of women (Symposium 179d)."[35]

"Earlier than the literary references is a sculptured representation of Orpheus with the ship Argo, found at Delphi, said to be of the sixth century BC."[17]

Mythology

[edit]

Origin

[edit]Some ancient Greek authors, such as Strabo and Plutarch, write of Orpheus as having a Thracian origin (through his father, Oeagrus).[2][3][4] Although these traditional accounts have been uncritically accepted by some historians,[2] they have been put into question by others, since it was only in the mid-/late 5th century that Orpheus acquired Thracian attributes.[36][37] Additionally, as André Boulanger notes, "the most characteristic features of Orphism—consciousness of sin, need of purification and redemption, infernal punishments—have never been found among the Thracians".[2] Indeed, the introduction of the worship of the Muses in the times of Archelaos, the genealogies featuring Apollo, Pierus and Methone, Orpheus' tomb in Leibethra and the importance of this gesture as a part of the king's cultural policy, makes the hypothesis of the Pierian, or Macedonian, roots of Orpheus, highly probable.[38][39] The testimonies referring to his death, grave and heroic worship, for example early attestations to the existence of a real, or fictitious, gravestone epigram of Orpheus, point most strongly to his Macedonian links.[38]

Early life

[edit]

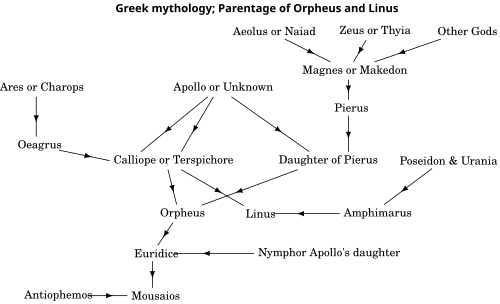

According to Apollodorus[5] and a fragment of Pindar,[40] Orpheus' father was Oeagrus, a Thracian king.[41] His mother was (1) the muse Calliope,[42] (2) her sister Polymnia,[43] (3) a daughter of Pierus,[44] son of Makednos or (4) lastly of Menippe, daughter of Thamyris.[45] Pindar, however, seems to call Orpheus the son of Apollo in his Pythian Odes,[46] and a scholium on this passage adds that the mythographer Asclepiades of Tragilus considered Orpheus to be the son of Apollo and Calliope.[47] According to Tzetzes, he was from Bisaltia.[48] His birthplace and place of residence was Pimpleia[49][50] close to the Olympus. Strabo mentions that he lived in Pimpleia.[31][50] According to the epic poem Argonautica, Pimpleia was the location of Oeagrus' and Calliope's wedding.[51] While living with his mother and her eight beautiful sisters in Parnassus, he met Apollo, who was courting the laughing muse Thalia. Apollo, as the god of music, gave Orpheus a golden lyre and taught him to play it.[52] Orpheus' mother taught him to make verses for singing. He is also said to have studied in Egypt.[53]

Orpheus is said to have established the worship of Hecate in Aegina.[54] In Laconia Orpheus is said to have brought the worship of Demeter Chthonia[55] and that of the Κόρες Σωτείρας (Kóres Sōteíras; 'Saviour Maidens').[clarification needed][56] Also in Taygetos a wooden image of Orpheus was said to have been kept by Pelasgians in the sanctuary of the Eleusinian Demeter.[57]

According to Diodorus Siculus, Musaeus of Athens was the son of Orpheus.[58]

Adventure as an Argonaut

[edit]

The Argonautica (Ἀργοναυτικά) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. Orpheus took part in this adventure and used his skills to aid his companions. Chiron told Jason that without the aid of Orpheus, the Argonauts would never be able to pass the Sirens—the same Sirens encountered by Odysseus in Homer's epic poem the Odyssey. The Sirens lived on three small, rocky islands called Sirenum scopuli and sang beautiful songs that enticed sailors to come to them, which resulted in the crashing of their ships into the islands. When Orpheus heard their voices, he drew his lyre and played music that was louder and more beautiful, drowning out the Sirens' bewitching songs. According to 3rd century BC Hellenistic elegiac poet Phanocles, Orpheus loved the young Argonaut Calais, "the son of Boreas, with all his heart, and went often in shaded groves still singing of his desire, nor was his heart at rest. But always, sleepless cares wasted his spirits as he looked at fresh Calais."[59][60]

Death of Eurydice

[edit]

The most famous story in which Orpheus figures is that of his wife Eurydice (sometimes referred to as Euridice and also known as Argiope). While walking among her people, the Cicones, in tall grass at her wedding, Eurydice was set upon by a satyr. In her efforts to escape the satyr, Eurydice fell into a nest of vipers and suffered a fatal bite on her heel. Her body was discovered by Orpheus who, overcome with grief, played such sad and mournful songs that all the nymphs and gods wept. On their advice, Orpheus traveled to the underworld. His music softened the hearts of Hades and Persephone, who agreed to allow Eurydice to return with him to earth on one condition: he should walk in front of her and not look back until they both had reached the upper world. Orpheus set off with Eurydice following; however, as soon as he had reached the upper world, he immediately turned to look at her, forgetting in his eagerness that both of them needed to be in the upper world for the condition to be met. As Eurydice had not yet crossed into the upper world, she vanished for the second time, this time forever.

The story in this form belongs to the time of Virgil, who first introduces the name of Aristaeus (by the time of Virgil's Georgics, the myth has Aristaeus chasing Eurydice when she was bitten by a serpent) and the tragic outcome.[61] Other ancient writers, however, speak of Orpheus' visit to the underworld in a more negative light; according to Phaedrus in Plato's Symposium,[62] the infernal gods only "presented an apparition" of Eurydice to him. In fact, Plato's representation of Orpheus is that of a coward, as instead of choosing to die in order to be with the one he loved, he instead mocked the gods by trying to go to Hades to bring her back alive. Since his love was not "true"—he did not want to die for love—he was actually punished by the gods, first by giving him only the apparition of his former wife in the underworld, and then by being killed by women. In Ovid's account, however, Eurydice's death by a snake bite is incurred while she was dancing with naiads on her wedding day.

Virgil wrote in his poem that Dryads wept from Epirus and Hebrus up to the land of the Getae (north east Danube valley) and even describes him wandering into Hyperborea and Tanais (ancient Greek city in the Don river delta)[64] due to his grief.

The story of Eurydice may actually be a late addition to the Orpheus myths. In particular, the name Eurudike ("she whose justice extends widely") recalls cult-titles attached to Persephone. According to the theories of poet Robert Graves, the myth may have been derived from another Orpheus legend, in which he travels to Tartarus and charms the goddess Hecate.[65]

The myth theme of not looking back, an essential precaution in Jason's raising of chthonic Brimo Hekate under Medea's guidance,[66] is reflected in the Biblical story of Lot's wife when escaping from Sodom. More directly, the story of Orpheus is similar to the ancient Greek tales of Persephone captured by Hades and similar stories of Adonis captive in the underworld. However, the developed form of the Orpheus myth was entwined with the Orphic mystery cults and, later in Rome, with the development of Mithraism and the cult of Sol Invictus.

Death

[edit]

According to a Late Antique summary of Aeschylus's lost play Bassarids, Orpheus, towards the end of his life, disdained the worship of all gods except Apollo. One early morning he went to the oracle of Dionysus at Mount Pangaion[67] to salute his god at dawn, but was ripped to shreds by Thracian Maenads for not honoring his previous patron (Dionysus) and was buried in Pieria.[27][68]

But having gone down into Hades because of his wife and seeing what sort of things were there, he did not continue to worship Dionysus, because of whom he was famous, but he thought Helios to be the greatest of the gods, Helios whom he also addressed as Apollo. Rousing himself each night toward dawn and climbing the mountain called Pangaion, he would await the Sun's rising, so that he might see it first. Therefore, Dionysus, being angry with him, sent the Bassarides, as Aeschylus the tragedian says; they tore him apart and scattered the limbs.[69]

Here his death is analogous with that of Pentheus, who was also torn to pieces by Maenads; and it has been speculated that the Orphic mystery cult regarded Orpheus as a parallel figure to or even an incarnation of Dionysus.[70] Both made similar journeys into Hades, and Dionysus-Zagreus suffered an identical death.[71] Pausanias writes that Orpheus was buried in Dion and that he met his death there.[72] He writes that the river Helicon sank underground when the women that killed Orpheus tried to wash off their blood-stained hands in its waters.[73] Other legends claim that Orpheus became a follower of Dionysus and spread his cult across the land. In this version of the legend, it is said that Orpheus was torn to shreds by the women of Thrace for his inattention.[74]

Ovid recounts that Orpheus

had abstained from the love of women, either because things ended badly for him, or because he had sworn to do so. Yet, many felt a desire to be joined with the poet, and many grieved at rejection. Indeed, he was the first of the Thracian people to transfer his affection to young boys and enjoy their brief springtime, and early flowering this side of manhood.

— Ovid, trans. A. S. Kline, Ovid: The Metamorphoses, Book X

Feeling spurned by Orpheus for taking only male lovers (eromenoi), the Ciconian women, followers of Dionysus,[75] first threw sticks and stones at him as he played, but his music was so beautiful even the rocks and branches refused to hit him. Enraged, the women tore him to pieces during the frenzy of their Bacchic orgies.[76] In Albrecht Dürer's drawing of Orpheus' death, based on an original, now lost, by Andrea Mantegna, a ribbon high in the tree above him is lettered Orfeus der erst puseran ("Orpheus, the first pederast").[77]

His head, still singing mournful songs, floated along with his lyre down the River Hebrus into the sea, after which the winds and waves carried them to the island of Lesbos,[78] at the city of Methymna; there, the inhabitants buried his head and a shrine was built in his honour near Antissa;[79] there his oracle prophesied, until it was silenced by Apollo.[80] In addition to the people of Lesbos, Greeks from Ionia and Aetolia consulted the oracle, and his reputation spread as far as Babylon.[81]

Orpheus' lyre was carried to heaven by the Muses, and was placed among the stars. The Muses also gathered up the fragments of his body and buried them at Leibethra[82] below Mount Olympus, where the nightingales sang over his grave. After the river Sys flooded[83] Leibethra, the Macedonians took his bones to Dion. Orpheus' soul returned to the underworld, to the fields of the Blessed, where he was reunited at last with his beloved Eurydice.

Another legend places his tomb at Dion,[67] near Pydna in Macedon. In another version of the myth, Orpheus travels to Aornum in Thesprotia, Epirus to an old oracle for the dead. In the end Orpheus commits suicide from his grief unable to find Eurydice.[84]

"Others said that he was the victim of a thunderbolt."[85]

Orphic poems and rites

[edit]

On the writings of Orpheus, Freeman, in the 1946 edition of The Pre- Socratic Philosophers writes:[86]

In the fifth and fourth centuries BC, there existed a collection of hexametric poems known as Orphic, which were the accepted authority of those who followed the Orphic way of life, and were by them attributed to Orpheus himself. Plato several times quotes lines from this collection; he refers in the Republic to a "mass of books of Musaeus and Orpheus", and in the Laws to the hymns of Thamyris and Orpheus, while in the Ion he groups Orpheus with Musaeus and Homer as the source of inspiration of epic poets and elocutionists. Euripides in the Hippolytus makes Theseus speak of the "turgid outpourings of many treatises", which have led his son to follow Orpheus and adopt the Bacchic religion. Alexis, the fourth century comic poet, depicting Linus offering a choice of books to Heracles, mentions "Orpheus, Hesiod, tragedies, Choerilus, Homer, Epicharmus". Aristotle did not believe that the poems were by Orpheus; he speaks of the "so-called Orphic epic", and Philoponus (seventh century AD) commenting on this expression, says that in the De Philosophia (now lost) Aristotle directly stated his opinion that the poems were not by Orpheus. Philoponus adds his own view that the doctrines were put into epic verse by Onomacritus. Aristotle when quoting the Orphic cosmological doctrines attributes them to "the theologoi", "the ancient poets", "those who first theorized about the gods".

[...]

Aelian (second century AD) gave the chief reason against believing in them: at the time when Orpheus is said to have lived, the Thracians knew nothing about writing. It came therefore to be believed that Orpheus taught, but left no writings, and that the epic poetry attributed to him was written in the sixth century BC by Onomacritus. Onomacritus was banished from Athens by Hipparchus for inserting something of his own into an oracle of Musaeus when entrusted with the editing of his poems. It may have been Aristotle who first suggested, in the lost De Philosophia, that Onomacritus also wrote the so-called Orphic epic poems. By the time when the Orphic writings began to be freely quoted by Christian and Neo-Platonist writers, the theory of the authorship of Onomacritus was accepted by many.

[...]

The Neo-Platonists quote the Orphic poems in their defence against Christianity, because Plato used poems which he believed to be Orphic. It is believed that in the collection of writings which they used there were several versions, each of which gave a slightly different account of the origin of the universe, of gods and men, and perhaps of the correct way of life, with the rewards and punishments attached thereto.

In addition to serving as a storehouse of mythological data along the lines of Hesiod's Theogony, Orphic poetry was recited in mystery-rites and purification rituals. Plato in particular tells of a class of vagrant beggar-priests who would go about offering purifications to the rich, a clatter of books by Orpheus and Musaeus in tow.[87] Those who were especially devoted to these rituals and poems often practiced vegetarianism and abstention from sex, and refrained from eating eggs and beans—which came to be known as the Orphikos bios, or "Orphic way of life".[88] W. K. C. Guthrie wrote that Orpheus was the founder of mystery religions and the first to reveal to men the meanings of the initiation rites.[89] There is also a reference, not mentioning Orpheus by name, in the pseudo-Platonic Axiochus, where it is said that the fate of the soul in Hades is described on certain bronze tablets which two seers had brought to Delos from the land of the Hyperboreans.

A number of Greek religious poems in hexameters were also attributed to Orpheus, as they were to similar miracle-working figures, like Bakis, Musaeus, Abaris, Aristeas, Epimenides, and the Sibyl. Of this vast literature, only two works survived whole: the Orphic Hymns, a set of 87 poems, possibly composed at some point in the second or third century, and the epic Orphic Argonautica, composed somewhere between the fourth and sixth centuries. Earlier Orphic literature, which may date back as far as the sixth century BC, survives only in papyrus fragments or in quotations. Some of the earliest fragments may have been composed by Onomacritus.[90]

The Derveni papyrus, found in Derveni, Macedonia (Greece) in 1962, contains a philosophical treatise that is an allegorical commentary on an Orphic poem in hexameters, a theogony concerning the birth of the gods, produced in the circle of the philosopher Anaxagoras, written in the second half of the fifth century BC.[91] The papyrus dates to around 340 BC, during the reign of Philip II of Macedon, making it Europe's oldest surviving manuscript.

Post-Classical interpretations

[edit]Classical music

[edit]

The Orpheus motif has permeated Western culture and has been used as a theme in all art forms. Early examples include the Breton lai Sir Orfeo from the early 13th century and musical interpretations like Jacopo Peri's Euridice (1600, though titled with his wife's name, the libretto is based entirely upon books X and XI of Ovid's Metamorphoses and therefore Orpheus' viewpoint is predominant).

Subsequent operatic and musical interpretations include:

- Claudio Monteverdi's L'Orfeo (1607)

- Luigi Rossi's Orfeo (1647)

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier's La descente d'Orphée aux enfers H.488 (1686). Charpentier also composed a cantata, Orphée descendant aux enfers H.471, (1683)

- Christoph Willibald Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice (1762)

- Joseph Haydn's last opera L'anima del filosofo, ossia Orfeo ed Euridice (1791)

- Franz Liszt's symphonic poem Orpheus (1854)

- Jacques Offenbach's operetta Orphée aux Enfers (1858)

- Igor Stravinsky's ballet Orpheus (1948)

- Two operas by Harrison Birtwistle: The Mask of Orpheus (1973–1984) and The Corridor (2009)

- Vladimir Genin's mono-opera (monodrama) Orpheus. Eurydike. Hermes (2017) after the text by Rainer Maria Rilke, premiered in 2023 in Pierre Boulez Saal Berlin

- Anaïs Mitchell's musical Hadestown (concept 2006 / Off-Broadway 2016 / Broadway 2019)

Literature

[edit]Rainer Maria Rilke's Sonnets to Orpheus (1922) are based on the Orpheus myth. Poul Anderson's Hugo Award-winning novelette "Goat Song", published in 1972, is a retelling of the story of Orpheus in a science fiction setting. Some feminist interpretations of the myth give Eurydice greater weight. Margaret Atwood's Orpheus and Eurydice Cycle (1976–1986) deals with the myth, and gives Eurydice a more prominent voice. Sarah Ruhl's Eurydice likewise presents the story of Orpheus' descent to the underworld from Eurydice's perspective. Ruhl removes Orpheus from the center of the story by pairing their romantic love with the paternal love of Eurydice's dead father.[92] David Almond's 2014 novel A Song for Ella Grey was inspired by the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, and won the Guardian Children's Fiction Prize in 2015.[93]

Film and stage

[edit]

Vinicius de Moraes’s play Orfeu da Conceição (1956), later adapted by Marcel Camus in the 1959 film Black Orpheus, tells the story in the modern context of a favela in Rio de Janeiro during Carnaval. Jean Cocteau's Orphic Trilogy – The Blood of a Poet (1930), Orpheus (1950) and Testament of Orpheus (1959) – was filmed over thirty years, and is based in many ways on the story. Philip Glass adapted the second film into the chamber opera Orphée (1991), part of an homage triptych to Cocteau. Anaïs Mitchell's 2010 folk opera musical Hadestown retells the tragedy of Orpheus and Eurydice with a score inspired by American blues and jazz, portraying Hades as the brutal work-boss of an underground mining city. Mitchell, together with director Rachel Chavkin, later adapted her album into a multiple Tony award-winning stage musical.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Garezou, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d Orpheus' Thracian origin, already maintained by Strabo and Plutarch, has been adopted again by E. Rohde (Psyche), by E. Mass (Orpheus), and by P. Perdrizet (Cultes et mythes du Pangée). But A. Boulanger has discerningly observed that “the most characteristic features of Orphism—consciousness of sin, need of purification and redemption, infernal punishments—have never been found among the Thracians”. For more see: Mircea Eliade (2011) History of Religious Ideas, Volume 2: From Gautama Buddha to the Triumph of Christianity, translated by Willard R. Trask, University of Chicago Press, p. 483, ISBN 022602735X.

- ^ a b Anthi Chrysanthou, Defining Orphism: The Beliefs, the ›teletae‹ and the Writings, (2020) Volume 94 of Trends in Classics - Supplementary Volumes, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3110678454: Orpheus' place of origin was Thrace and according to most ancient sources he was the son of Oeagrus and muse Kalliope.

- ^ a b Androtion, an Attidographer writing in the fourth century BCE, focused precisely on Orpheus' Thracian origin, and the well-known illiteracy of his people...For more see: Graziosi, Barbara (2018). "Still Singing: The Case of Orpheus". In Nora Goldschmidt; Barbara Graziosi (eds.). Tombs of the Ancient Poets: Between Literary Reception and Material Culture. Oxford University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0192561039.

- ^ a b Son of Oeagrus and Calliope: Apollodorus, 1.3.2 & 1.9.16

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.9.16.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark (2020). "Orpheus". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- ^ Geoffrey Miles, Classical Mythology in English Literature: A Critical Anthology (Routledge, 1999), p. 54.

- ^ Pausanias, 2.30.2

- ^ Janko, Richard (2001). "The Derveni Papyrus ("Diagoras of Melos, Apopyrgizontes Logoi?"): A New Translation". Classical Philology. 96: 1–32. doi:10.1086/449521. ISSN 0009-837X. S2CID 162191106.

- ^ Gunk, Wretch (January 1865). The Lithica -"Orpheus on Gems" taken from Natural History of Precious Stones and Gems by Charles William King.

- ^ Guthrie, William Keith (1993-10-10). Orpheus and Greek Religion: A Study of the Orphic Movement. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02499-8.

- ^ Cf. "Ὀρφανός" in: Etymological Dictionary of Greek, ed. Robert S. P. Beekes. First published online[where?] October 2010.

- ^ Cobb, Noel. Archetypal Imagination, Hudson, New York: Lindisfarne Press, p. 240. ISBN 0-940262-47-9

- ^ Freiert, William K. (1991). Pozzi, Dora Carlisky; Wickersham, John M. (eds.). "Orpheus: A Fugue on the Polis". Myth and the Polis. Cornell University Press: 46. ISBN 0-8014-2473-9.

- ^ Miles, Geoffrey. Classical Mythology in English Literature: A Critical Anthology, London: Routledge, 1999, p. 57. ISBN 0-415-14755-7

- ^ a b c d Freeman 1946, p. 1.

- ^ Ibycus, Fragments 17 (Diehl); M. Owen Lee, Virgil as Orpheus: A Study of the Georgics State University of New York Press, Albany (1996), p. 3.

- ^ Freeman 1948, p. 1.

- ^ Aristotle (1952). W. D. Ross; John Alexander Smith (eds.). The Works of Aristotle. Vol. XII–Fragments. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 80.

- ^ Pindar, Pythian Odes 4.176

- ^ Pindar, fr. 126.9

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.3.2; Argonautica 1.23 & Orphic Hymn 24.12

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.3.2; Euripides, Iphigeneia at Aulis 1212 and The Bacchae, 562; Ovid, Metamorphoses 11: "with his songs, Orpheus, the bard of Thrace, allured the trees, the savage animals, and even the insensate rocks, to follow him."

- ^ Others to brave the nekyia were Odysseus, Theseus and Heracles; Perseus also overcame Medusa in a chthonic setting.

- ^ A single literary epitaph, attributed to the sophist Alcidamas, credits Orpheus with the invention of writing. See Ivan Mortimer Linforth, "Two Notes on the Legend of Orpheus", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 62, (1931):5–17.

- ^ a b Apollodorus, 1.3.2. "Orpheus also invented the mysteries of Dionysus, and having been torn in pieces by the Maenads he is buried in Pieria."

- ^ Apollonius, Argonautica passim

- ^ Apollodorus, Library and Epitome, 2.4.9. This Linus was a brother of Orpheus; he came to Thebes and became a Theban.

- ^ Godwin, William (1876). "Lives of the Necromancers". p. 44.

- ^ a b Strabo, 7.7: "At the base of Olympus is a city Dium. And it has a village near by, Pimpleia. Here lived Orpheus, the Ciconian, it is said – a wizard who at first collected money from his music, together with his soothsaying and his celebration of the orgies connected with the mystic initiatory rites, but soon afterwards thought himself worthy of still greater things and procured for himself a throng of followers and power. Some, of course, received him willingly, but others, since they suspected a plot and violence, combined against him and killed him. And near here, also, is Leibethra."

- ^ Gregory Nagy, Archaic Period (Greek Literature, Volume 2), ISBN 0-8153-3683-7, p. 46.

- ^ Index in Eustathii commentarios in Homeri Iliadem et Odysseam by Matthaeus Devarius, p. 8.

- ^ Pausanias, 6.20.18: "A man of Egypt said that Pelops received something from Amphion the Theban and buried it where is what they call Taraxippus, adding that it was the buried thing which frightened the mares of Oenomaus, as well as those of every charioteer since. This Egyptian thought that Amphion and the Thracian Orpheus were clever magicians, and that it was through their enchantments that the beasts came to Orpheus, and the stones came to Amphion for the building of the wall. The most probable of the stories in my opinion makes Taraxippus a surname of Horse Poseidon."

- ^ a b c Smith, William (1870). Dictionary of Greek And Roman Biography And Mythology. Vol. 3. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. p. 60. ark:/13960/t23b60t0r.

- ^ Watson, Sarah Burges (2013). "Muses of Lesbos or (Aeschylean) Muses of Pieria? Orpheus' Head on a Fifth-century Hydria". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 53 (3): 441–460. ISSN 2159-3159.

- ^ Lissarague, François (1993). "«Musica e storia», II, 1994". Fondazione Ugo e Olga Levi (in Italian). pp. 273–274.

- ^ a b Mojsik, Tomasz (2020). "The "Double Orpheus": between Myth and Cult". Mythos. Rivista di Storia delle Religioni (14). doi:10.4000/mythos.1674. ISSN 1972-2516.

- ^ Mojsik, Tomasz (2022). Orpheus in Macedonia: Myth, Cult and Ideology. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 93, 137. ISBN 978-1-350-21319-7.

- ^ Kerényi, p. 280; Pindar fr. 128c Race (Threnos 3) 11–12.

- ^ compare Apollonius Rhodius, 1.23–25

- ^ Apollonius Rhodius, 1.23–25

- ^ Scholia ad Apollonius Rhodius, 1.23 with Asclepiades as the authority

- ^ In Pausanias, 9.30.4, the author claimed that "... There are many untruths believed by the Greeks, one of which is that Orpheus was a son of the Muse Calliope, and not of the daughter of Pierus."

- ^ Tzetzes, Chiliades 1.12 line 306

- ^ Gantz, p. 725; Pindar, Pythian 4.176–7.

- ^ Gantz, p. 725; BNJ 12 F6a = [Scholia on Pindar's Pythian, 4.313a].

- ^ Tzetzes, Chiliades 1.12 line 305

- ^ William Keith Guthrie and L. Alderlink, Orpheus and Greek Religion (Mythos Books), 1993, ISBN 0-691-02499-5, p. 61 f.: "[…] is a city Dion. Near it is a village called Pimpleia. It was there they say that Orpheus the Kikonian lived."

- ^ a b Jane Ellen Harrison, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion (Mythos Books), 1991, ISBN 0-691-01514-7, p. 469: "[…] near the city of Dium is a village called Pimpleia where Orpheus lived."

- ^ The Argonautica, book I (ll. 23–34), "First then let us name Orpheus whom once Calliope bare, it is said, wedded to Thracian Oeagrus, near the Pimpleian height."

- ^ Hoopes And Evslin, The Greek Gods, ISBN 0-590-44110-8, ISBN 0-590-44110-8, 1995, p. 77: "His father was a Thracian king; his mother the muse Calliope. For a while he lived on Parnassus with his mother and his eight beautiful aunts and there met Apollo who was courting the laughing muse Thalia. Apollo was taken with Orpheus, gave him his little golden lyre and taught him to play. And his mother Calliope, the muse presiding over epic poetry, taught him to make verses for singing."

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 4.25.2–4

- ^ Pausanias, Corinth, 2.30.1 [2]: "Of the gods, the Aeginetans worship most Hecate, in whose honor every year they celebrate mystic rites which, they say, Orpheus the Thracian established among them. Within the enclosure is a temple; its wooden image is the work of Myron, and it has one face and one body. It was Alcamenes, in my opinion, who first made three images of Hecate attached to one another, a figure called by the Athenians Epipurgidia (on the Tower); it stands beside the temple of the Wingless Victory."

- ^ Pausanias, Laconia, 3.14.1,[5]: "[…] but the wooden image of Thetis is guarded in secret. The cult of Demeter Chthonia (of the Lower World) the Lacedaemonians say was handed on to them by Orpheus, but in my opinion it was because of the sanctuary in Hermione that the Lacedaemonians also began to worship Demeter Chthonia. The Spartans have also a sanctuary of Serapis, the newest sanctuary in the city, and one of Zeus surnamed Olympian."

- ^ Pausanias, Laconia, 3.13.1: "Opposite the Olympian Aphrodite the Lacedaemonians have a temple of the Saviour Maid. Some say that it was made by Orpheus the Thracian, others by Abairis when he had come from the Hyperboreans."

- ^ Pausanias, Laconia, 3.20.1,[5]: "Between Taletum and Euoras is a place they name Therae, where they say Leto from the Peaks of Taygetus […] is a sanctuary of Demeter surnamed Eleusinian. Here according to the Lacedaemonian story Heracles was hidden by Asclepius while he was being healed of a wound. In the sanctuary is a wooden image of Orpheus, a work, they say, of Pelasgians."

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 4.25.1–2

- ^ Katherine Crawford (2010). The Sexual Culture of the French Renaissance. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-521-76989-1.

- ^ John Block Friedman (2000-05-01). Orpheus in the Middle Ages. Syracuse University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8156-2825-5.

- ^ M. Owen Lee, Virgil as Orpheus: A Study of the Georgics, State University of New York Press, Albany (1996), p. 9.

- ^ Symposium 179d

- ^ "Attributed to the Painter of London E 497: Bell-krater (24.97.30) – Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History – The Metropolitan Museum of Art". metmuseum.org.

- ^ "The Georgics of Virgil: Fourth Book". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ Robert Graves, The Greek Myths, Penguin Books Ltd., London (1955), Volume 1, Chapter 28, "Orpheus", p. 115.

- ^ Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, book III: "Let no footfall or barking of dogs cause you to turn around, lest you ruin everything", Medea warns Jason; after the dread rite, "The son of Aison was seized by fear, but even so he did not turn round..." (Richard Hunter, translator).

- ^ a b William Keith Guthrie and L. Alderlink, Orpheus and Greek Religion, ISBN 0-691-02499-5, p. 32

- ^ Wilson, N., Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece, Routledge, 2013, ISBN 113678800X, p. 702: "His grave and cult belong not to Thrace but to Pierian Macedonia, northeast of Mount Olympus, a region that the Thracians had once inhabited".

- ^ Homer; Bryant, William Cullen (1809). The Iliad of Homer. Ashmead.

- ^ Mark P. O. Morford, Robert J. Lenardon, Classical Mythology, p. 279.

- ^ Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, volume 88, p. 211

- ^ Pausanias, 9.30.1 A more commonly accepted death of Orpheus was that after returning from the Underworld, without Eurydice, Orpheus fell into a great depression. Orpheus would only play sad music on his lyre, and took no interest in the *Maenads, finding them a painful reminder of his past. Orpheus instead took romantic interest in men, which drove the Maenads to the point of insanity, and one day when they were drunk they tore him apart. Orpheus' head sailed down the river to distant *Lesbos where it there lived on with the gift of prophecy. Description of Greece: Boeotia], 9.30.1. The Macedonians who dwell in the district below Mount Pieria and the city of Dium say that it was here that Orpheus met his end at the hands of the women. Going from Dium along the road to the mountain, and advancing twenty stades, you come to a pillar on the right surmounted by a stone urn, which according to the natives contains the bones of Orpheus.

- ^ Pausanias, Boeotia 9.30.1. There is also a river called Helicon. After a course of seventy-five stades the stream hereupon disappears under the earth. After a gap of about twenty-two stades the water rises again, and under the name of Baphyra instead of Helicon flows into the sea as a navigable river. The people of Dium say that at first this river flowed on land throughout its course. But, they go on to say, the women who killed Orpheus wished to wash off in it the blood-stains, and thereat the river sank underground, so as not to lend its waters to cleanse manslaughter

- ^ "Orpheus". The Columbia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ Patricia Jane Johnson (2008). Ovid Before Exile: Art and Punishment in the Metamorphoses. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-299-22400-4. "by the Ciconian women".

- ^ Ovid, trans. A. S. Kline (2000). Ovid: The Metamorphoses. Book XI.

- ^ Heinrich Wölfflin (2013). Drawings of Albrecht Dürer. Courier Dover. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-486-14090-2.

- ^ Carlos Parada "His head fell into the sea and was cast by the waves upon the island of Lesbos where the Lesbians buried it, and for having done this the Lesbians have the reputation of being skilled in music."[full citation needed]

- ^ Recently[when?] a cave was identified as the oracle of Orpheus nearby the modern village of Antissa; see Harissis H. V. et al. "The Spelios of Antissa; The oracle of Orpheus in Lesvos" Archaiologia kai Technes 2002; 83:68–73 (article in Greek with English abstract)

- ^ Flavius Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana, [1]

- ^ Godwin, William (1876). "Lives of the Necromancers". p. 46.

- ^ Marcele Detienne, The Writing of Orpheus: Greek Myth in Cultural Context, ISBN 0-8018-6954-4, p. 161

- ^ Pausanias, Boeotia, 9.30.1 [11] Immediately when night came the god sent heavy rain, and the river Sys (Boar), one of the torrents about Olympus, on this occasion threw down the walls of Libethra, overturning sanctuaries of gods and houses of men, and drowning the inhabitants and all the animals in the city. When Libethra was now a city of ruin, the Macedonians in Dium, according to my friend of Larisa, carried the bones of Orpheus to their own country.

- ^ Pausanias, Boeotia, 9.30.1. Others have said that his wife died before him, and that for her sake he came to Aornum in Thesprotis, where of old was an oracle of the dead. He thought, they say, that the soul of Eurydice followed him, but turning round he lost her, and committed suicide for grief. The Thracians say that such nightingales as nest on the grave of Orpheus sing more sweetly and louder than others.

- ^ Freeman 1946, p. 3.

- ^ Freeman 1946, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Plato. The Republic 364c–d.

- ^ Moore, p. 56: "the use of eggs and beans was forbidden, for these articles were associated with the worship of the dead".

- ^ Guthrie, pp. 17–18. "As founder of mystery-religions, Orpheus was first to reveal to men the meaning of the rites of initiation (teletai). We read of this in both Plato and Aristophanes (Aristophanes, Frogs, 1032; Plato, Republic, 364e, a passage which suggests that literary authority was made to take the responsibility for the rites)". Guthrie goes on to write about "This less worthy but certainly popular side of Orphism is represented for us again by the charms or incantations of Orpheus which we may also read of as early as the fifth century. Our authority is Euripides, a reference in the Alcestis of Euripides to certain Thracian tablets which "the voice of Orpheus had inscribed" with pharmaceutical lore. The scholiast, commenting on the passage, says that there exist on Mt. Haemus certain writings of Orpheus on tablets. We have already noticed the 'charm on the Thracian tablets' in the Alcestis and in Cyclops one of the lazy and frightened Satyrs, unwilling to help Odysseus in the task of driving the burning stake into the single eye of the giant, exclaims: 'But I know a spell of Orpheus, a fine one, which will make the brand step up of its own accord to burn this one-eyed son of Earth' (Euripides, Cyclops 646 = Kern, test. 83)."

- ^ Freeman 1948, p. 1.

- ^ Janko, Richard (2006). Tsantsanoglou, K.; Parássoglou, G. M.; Kouremenos, T. (eds.). "The Derveni Papyrus". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Studi e testi per il 'Corpus dei papiri filosofici greci e latini'. 13. Florence: Olschki.

- ^ Isherwood, Charles (2007-06-19). "The Power of Memory to Triumph Over Death". The New York Times.

- ^ "David Almond wins Guardian children's fiction prize". The Guardian. 2015-11-19. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

Bibliography

[edit]- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheke I, iii, 2; ix, 16 & 25;

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica I, 23–34; IV, 891–909.

- Bernabé, Alberto (1996), Poetae epici Graeci: Testimonia et fragmenta, Pars I, Bibliotheca Teubneriana, Stuttgart and Leipzig, Teubner, 1996. ISBN 978-3-815-41706-5. Online version at De Gruyter.

- Bernabé, Alberto (2005), Poetae epici Graeci: Testimonia et fragmenta, Pars II: Orphicorum et Orphicis similium testimonia et fragmenta, Fasc 2, Bibliotheca Teubneriana, Munich and Leipzig, K. G. Saur Verlag, 2005. ISBN 978-3-598-71708-6. Online version at De Gruyter.

- Freeman, Kathleen (1946), The Pre-Socratic Philosophers: Companion to Diels, Fragmente Der Vorsokratiker, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1946. Internet Archive.

- Freeman, Kathleen (1948), Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers: A Complete Translation of the Fragments in Diels, Fragmente Der Vorsokratiker, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1948. Internet Archive.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Garezou, Maria-Xeni, "Orpheus", in Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC). VII.1: Oidipous – Theseus, Zurich and Munich, Artemis Verlag, 1994. ISBN 3760887511. Internet Archive.

- Guthrie, William Keith Chambers, Orpheus and Greek Religion: a Study of the Orphic Movement, 1935.

- Kerenyi, Karl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. New York/London: Thames and Hudson.

- Moore, Clifford H., Religious Thought of the Greeks, 1916. Kessinger Publishing (April 2003). ISBN 978-0-7661-5130-7

- Ossoli, Margaret Fuller, Orpheus, a sonnet about his trip to the underworld.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses X, 1–105; XI, 1–66;

- Pindar, Olympian Odes. Pythian Odes, edited and translated by William H. Race, Loeb Classical Library No. 56, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-674-99564-2. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Pindar, Nemean Odes. Isthmian Odes. Fragments, Edited and translated by William H. Race. Loeb Classical Library No. 485. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-674-99534-5. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Christoph Riedweg, "Orfeo", in: S. Settis (a cura di), I Greci: Storia Cultura Arte Società, volume II, 1, Turin 1996, 1251–1280.

- Christoph Riedweg, "Orpheus oder die Magie der musiké. Antike Variationen eines einflussreichen Mythos", in: Th. Fuhrer / P. Michel / P. Stotz (Hgg.), Geschichten und ihre Geschichte, Basel 2004, 37–66.

- Segal, Charles (1989). Orpheus : The Myth of the Poet. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3708-1.

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Orpheus"

- West, Martin L., The Orphic Poems, 1983. There is a sub-thesis in this work that early Greek religion was heavily influenced by Central Asian shamanistic practices. One major point of contact was the ancient Crimean city of Olbia.

- Wise, R. Todd, A Neocomparative Examination of the Orpheus Myth As Found in the Native American and European Traditions, 1998. UMI. The thesis explores Orpheus as a single mythic structure present in traditions that extend from antiquity to contemporary times and across cultural contexts.

- Wroe, Ann, Orpheus: The Song of Life, The Overlook Press, New York, 2012.

External links

[edit]- Greek Mythology Link, Orpheus

- The Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (images of Orpheus)

- Orphicorum fragmenta, Otto Kern (ed.), Berolini apud Weidmannos, 1922.

- Freese, John Henry (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 327–329.

Orpheus

View on GrokipediaName and Origins

Etymology

The name Orpheus appears in ancient Greek as Ὀρφεύς (Orpheús), with the accent on the second syllable in Attic dialect, pronounced approximately as "or-PHEU-s."[6] This form reflects the standard Ionic-Attic spelling, though variations occur in other dialects and later Latin transcriptions as Orpheus.[6] Scholars have proposed several etymological derivations for the name, often linking it to themes of loss and obscurity given Orpheus's Thracian origins. One common interpretation connects it to the Greek word ὄρφνη (orphnē), meaning "the darkness of night," suggesting associations with mystery and the underworld.[7] Alternatively, it may derive from the Indo-European root *h₃órbʰos or *orbho-, implying "orphan" or "bereft," possibly influenced by Thracian linguistic elements where similar roots denote deprivation or separation; this aligns with Thrace's cultural context, as Orpheus is consistently portrayed as a figure from that region.[8] Non-Greek influences, such as Thracian or Phrygian substrates, are suggested by the name's phonetic structure, which does not fully align with typical Hellenic patterns, though direct evidence remains speculative.[8] An ancient folk etymology appears in the work of the Roman mythographer Fulgentius, who derived Orpheus from the Greek ὀρειοφώνη (oreio-phōnē), meaning "matchless sound" or "best voice," symbolizing poetic inspiration and musical prowess.[9] Symbolically, these interpretations evoke Orpheus's role in themes of loss, as in his bereavement, and mystical connections to the underworld, where darkness and orphanhood underscore the enigmatic quality of his legendary artistry.[8]Historical and Cultural Context

Orpheus is portrayed in ancient Greek traditions as a semi-legendary figure originating from Thrace, with his earliest attestations in literature dating to the 6th century BCE, though possible roots in pre-Hellenic Thracian bardic traditions may extend to the Bronze Age; some recent scholarship proposes a historical kernel as a Thracian king-priest from the mid-2nd millennium BCE.[10][11] As a Thracian bard and musician, Orpheus embodies a blend of myth and possible historical elements, reflecting the cultural exchanges between Thracian and Greek societies in the Archaic period.[11] The figure of Orpheus draws heavily from Thracian shamanistic practices, which influenced Greek mythology through themes of ecstatic ritual, soul journeying, and communion with the divine, often intertwined with Dionysian elements such as frenzy and mystery cults.[12] These influences highlight Orpheus's role as a mediator between the human and supernatural realms, contrasting with the more structured anthropomorphic worship of Olympian gods in mainstream Greek religion. Thracian shamanism, characterized by prophetic music and initiatory experiences, contributed to the portrayal of Orpheus as a charismatic figure capable of charming nature and the underworld.[13]Mythological Biography

Birth and Early Life

In Greek mythology, Orpheus was born in the region of Thrace, near the Pimpleian height, to the Muse Calliope and the Thracian king Oeagrus.[14] Some ancient accounts alternatively identify his father as the god Apollo, emphasizing his divine musical heritage.[15] This parentage positioned Orpheus within both mortal Thracian royalty and the immortal realm of the Muses, reflecting the blend of human and divine elements in his legendary origins.[16] From an early age, Orpheus received instruction in music from Apollo, who presented him with a golden lyre and taught him its mastery, while the Muses, led by his mother Calliope, trained him in the art of song.[16] These formative experiences endowed him with unparalleled skill, enabling his lyre playing and voice to exert supernatural influence over nature, charming wild animals, taming rivers, and even moving trees and rocks to dance.[17] Such abilities marked his childhood as one of prodigious talent, rooted in divine tutelage rather than mere practice. Orpheus's early poetic gifts further distinguished him, as he composed verses and hymns that praised the gods and established foundational forms of song. The poet Pindar hailed him as the "father of songs," crediting Orpheus with originating melodic poetry that bridged mortal expression and divine inspiration.[18] These initial associations with Apollo and the Muses solidified his role as a archetypal bard, whose Thracian upbringing infused his art with the region's mystical traditions.Quest with the Argonauts

Orpheus, renowned for his musical prowess, was recruited by Jason to join the Argonauts' expedition to Colchis in search of the Golden Fleece, a quest mythically dated to around the 13th century BCE. As the son of the Muse Calliope and the Thracian king Oeagrus, Orpheus was selected for his ability to inspire and harmonize the crew through song, ensuring unity among the diverse heroes assembled at Pagasae. In Apollonius Rhodius's Argonautica, he is listed among the first heroes to board the Argo, his lyre poised to counter perilous enchantments and soothe tensions during the voyage.[17] During the journey, Orpheus's music played a crucial role in maintaining order among the Argonauts, particularly in calming disputes that arose from the crew's strong personalities, including figures like Heracles. His songs fostered concord, as seen when he led hymns that unified the group after conflicts, such as the boxing match with the Bebryces in Book 2, where his lyre accompanied celebrations and reinforced solidarity. This protective power of his music extended to navigational challenges; following the aid from the seer Phineus, whom the Argonauts had liberated from the torment of the Harpies by the Boreads, Orpheus performed a hymn to Apollo on the island of Thynias, which soothed the crew and dispelled lingering discord, allowing them to proceed with renewed harmony.[19] The most dramatic intervention came at the island of the Sirens, where Orpheus's lyre overpowered their deadly song, preventing the crew from succumbing to enchantment. In Argonautica Book 4, as the Sirens lured the Argonauts toward destruction with their irresistible melodies, Orpheus struck his lyre and sang a competing strain, drowning out their voices and compelling the creatures to silence; the crew rowed past safely, crediting his music with their deliverance. This act underscored music's capacity to shield against supernatural threats, a theme echoed in the later Orphic Argonautica, where Orpheus narrates overpowering the Sirens through his divine voice, charming them into self-destruction.[5][20]Marriage to Eurydice and Underworld Descent

Orpheus, renowned for his musical talents, married Eurydice, a beautiful nymph, in a union celebrated with song and dance.[21] However, tragedy struck on their wedding day when Eurydice, fleeing the advances of Aristaeus, stepped on a viper hidden in the grass and died from its venomous bite.[22] Overcome with grief, Orpheus vowed to retrieve her from the Underworld, descending through the gates at Taenarus with his lyre in hand.[2] In Virgil's account, as he journeyed through the realm of the dead, Orpheus's music stupefied the underworld, causing the shades to weep, the Furies to shed tears for the first time, and Cerberus to hold his three mouths gaping in awe.[22] Continuing onward, Orpheus's song culminated in the throne room of Hades and Persephone.[22] There, Orpheus pleaded eloquently, his lyre accompanying a lament of profound love and loss, which pierced even the hearts of the Underworld's rulers.[21] Moved by his artistry, Hades agreed to release Eurydice, stipulating that Orpheus must lead her back to the world above without turning to look at her until they both emerged into the light.[2] They began the ascent, Orpheus walking ahead, guided by the faint sound of her footsteps.[21] Yet, as they neared the threshold of the living world, doubt gripped Orpheus; fearing she had not followed, he glanced back. In that instant, Eurydice vanished, reclaimed by the shadows, her final words a fading "farewell."[21] This katabasis and its tragic conclusion underscore enduring themes of love's desperation and the irreversible boundaries between life and death in ancient mythology, with variants in Greek sources like Ovid emphasizing the emotional impact on Hades without detailing interactions with guardians.[22][23]Death and Aftermath

Following the loss of Eurydice, Orpheus withdrew from the company of women, devoting himself instead to the love of young boys and composing verses in their praise, which provoked the fury of the Thracian Maenads.[24] During a Dionysian rite in Thrace, the Maenads, in a state of ecstatic frenzy, assaulted Orpheus with stones and weapons, but his enchanting music caused the projectiles to fall harmlessly at his feet; undeterred, they tore him limb from limb in a ritual act of sparagmos, silencing his voice forever.[24] Orpheus's severed head, still lamenting Eurydice, and his lyre floated down the Hebrus River into the sea, carried by winds and waves to the shores of Lesbos, where they continued to emit mournful melodies.[24] The Muses gathered his scattered remains and interred them at Leibethra, a city at the foot of Mount Olympus in Pieria, establishing a tomb that became a site of reverence.[25] In the aftermath, Orpheus's head was enshrined on Lesbos, where it delivered prophecies from a cave until Apollo, fearing rivalry with his own oracle at Delphi, silenced it and relocated the head to a safer site.[26] Meanwhile, Zeus, moved by the lyre's sorrowful song, placed it among the stars as the constellation Lyra to commemorate Orpheus's musical legacy.[24] The relics at Leibethra later inspired local cults, though the city faced destruction after a Delphic oracle foretold ruin if the sun beheld Orpheus's bones, which were then relocated at night by the inhabitants to prevent further calamity.[25]Orphism and Ancient Legacy

Orphic Cults and Mysteries

The nature and extent of Orphism as a distinct religious tradition remain subjects of debate among scholars, with some viewing it as a coherent esoteric movement in ancient Greece and others as a modern scholarly construct encompassing a variety of Dionysiac and eschatological practices attributed to the mythical figure Orpheus.[27] Ideas associated with Orphism are thought to have emerged during the 6th century BCE, persisting through the 2nd century BCE and influencing later practices into the early centuries CE. They emphasized the soul's divine origin and its entrapment in the material body due to a primordial crime, often reconstructed as linked to the Titans' dismemberment of the infant Dionysus-Zagreus in certain mythic accounts, from whose ashes humanity arose bearing both Titanic elements and a spark of divinity—though this narrative and its implications for inherited guilt are not universally accepted as central to an Orphic doctrine.[27][28] Associated ideas included the immortality of the soul, its purification through ascetic practices to escape the cycle of reincarnation (metempsychosis), and ethical living to achieve liberation and a blessed afterlife.[28] This perspective contrasted with mainstream Greek polytheism by prioritizing individual salvation over civic rituals, drawing on myths attributed to Orpheus as a revealer of cosmic secrets.[29] A key tenet in reconstructions of Orphism was the purification of the soul (psychē) from bodily pollution and inherited sin, achieved through rituals and lifestyle choices that elevated the spiritual over the physical. Adherents believed the soul, imprisoned in the body as in a tomb (sōma-sēma), could be cleansed to avoid further reincarnations into lower forms, such as animals, and instead ascend to divine realms.[28][27] Vegetarianism formed a cornerstone of this purification in some accounts, prohibiting the consumption of meat to avoid the pollution of animal sacrifice and to curb passions like gluttony and violence, thereby preserving the soul's sanctity.[29][28] Plato references this "Orphic life" (bios Orphikos) in his Laws (782c), praising its abstinence from flesh as a path to moral and spiritual refinement.[29] Reincarnation was viewed as a punitive cycle for unpurified souls, with release possible only after multiple lives of atonement, as echoed in early testimonia like Pindar's fragments (fr. 133) and later philosophical adaptations.[27] Initiation rites, known as teletai, were the practical core of practices associated with Orphism, offering participants a symbolic enactment of death and rebirth to prepare for the afterlife. These private ceremonies, often conducted by itinerant specialists called orpheotelestai, involved chanting Orphic hymns to invoke deities like Dionysus and Persephone, periods of fasting to induce visionary states, and rituals simulating the soul's journey through underworld trials.[30][28] Unlike the public, agrarian-focused Eleusinian Mysteries centered on Demeter and Persephone's myth, Orphic teletai were more individualistic and eschatological, emphasizing personal atonement and esoteric knowledge over communal fertility rites.[28] Gold leaves inscribed with instructions—such as passwords like "I am a child of Earth and starry Heaven"—served as amulets buried with initiates to guide them past guardians in the afterlife, underscoring the rites' focus on mnemonic and symbolic rebirth.[29][28] Orpheus himself was mythologized as the archetypal mystagogue, a prophetic figure who descended to the underworld and returned with divine teachings on the soul's nature and cosmic order, imparting them first to the Thracians and then to broader Greek audiences. Legends portrayed him as the founder of these mysteries, using his lyre and hymns to reveal hidden truths about purification and immortality, positioning him as a bridge between humanity and the gods.[28] This role elevated Orpheus beyond a mere musician to a spiritual guide, whose myths inspired the tradition's rituals and texts.[28] Ideas associated with Orphism spread from its Thracian and Attic origins to Magna Graecia in southern Italy and Sicily by the 5th century BCE, where it intertwined with local Pythagorean communities, and later to Rome, influencing Bacchic cults suppressed in 186 BCE but persisting underground. Evidence includes the Derveni Papyrus, a 4th-century BCE commentary on an Orphic theogony discovered near Thessaloniki, which details ritual interpretations for Bacchic initiates and allegorizes myths to explain soul liberation.[30] Inscriptions on gold tablets from sites like Hipponion in Calabria (4th century BCE) provide ritual phrases for the afterlife, while bone tablets from Olbia in the Black Sea region (5th century BCE) attest to early Orphic-Dionysiac practices.[27][29] Roman-era evidence, such as a 3rd-century CE inscription edited by Cumont, further documents Orphic gods and rites in Italic contexts.[27] These artifacts confirm the adaptability and enduring appeal of ideas labeled as Orphic across the Greco-Roman world.Orphic Texts and Poetry

The corpus of Orphic literature encompasses a diverse array of texts attributed to the mythical figure Orpheus, including hymns, theogonies, and katabasis poems, which were later compiled into the Orphic Rhapsodies, a comprehensive collection dating from the Hellenistic period to the early Roman era, approximately the 3rd century BCE to the 2nd century CE.[31][32] These works, preserved primarily through quotations in later authors, form a pseudepigraphic tradition, meaning they were not composed by a historical Orpheus but ascribed to him to lend religious authority, with the earliest fragments appearing in Herodotus's Histories (c. 5th century BCE) and Plato's dialogues (c. 4th century BCE).[31] Full or extensive versions of these texts survive in the writings of Neoplatonist philosophers like Proclus (5th century CE), who extensively quoted the Orphic theogony in his Commentary on Plato's Timaeus.[31] Central to the Orphic theogonies are creation myths that diverge significantly from Hesiod's Theogony, emphasizing a primordial cosmic egg hatched by the serpent-god Chronos (Time) to birth the first divine entities, Phanes and Night, rather than the more linear succession of Titans and Olympians.[31] A pivotal narrative involves the infant Dionysus Zagreus, son of Zeus and Persephone, who is lured, dismembered, and consumed by the Titans, symbolizing humanity's dual nature as both divine (from Dionysus) and Titanic (from the ashes of the slain Titans, out of which mortals are formed).[32] These myths underscore the soul's immortality and its entrapment in a cycle of reincarnation due to this primordial crime, offering paths to purification and liberation through esoteric knowledge and ritual.[31] The Orphic hymns, a collection of 87 short invocatory poems likely composed in the 2nd or 3rd century CE, invoke deities in a structured sequence mimicking a nocturnal mystery ritual, progressing from chthonic figures like Hecate and Nyx to Olympians and culminating in Dionysus and Dawn, with themes of protection against divine madness and initiation into Bacchic ecstasy.[33] Katabasis poems, depicting descents to the underworld (often by heroes like Heracles or Theseus rather than Orpheus himself), explore cosmic geography and the soul's journey, reinforcing eschatological ideas of afterlife navigation and reincarnation without direct focus on personal salvation narratives.[34] The pseudepigraphic nature of these texts facilitated their influence on philosophical traditions, notably Pythagoreanism, which adopted Orphic doctrines of soul immortality and metempsychosis, as evidenced by shared motifs in funerary practices.[31] Neoplatonists such as Proclus and Damascius integrated Orphic theogonies into their metaphysical systems, viewing them as hieratic revelations bridging Platonic philosophy and divine hierarchies.[31] This legacy is materially attested in gold leaf amulets (lamellae aureae) from 5th century BCE to 3rd century CE graves in Magna Graecia and Thessaly, inscribed with Orphic verses guiding the soul through the afterlife, such as declarations of purity ("I come pure from the pure") and instructions to avoid polluted springs, blending Orphic theology with Dionysiac and Pythagorean elements.[35] These texts were occasionally employed in cultic settings to accompany mystery initiations, though their primary role remained theological and instructional.[31]Depictions in Art and Literature

Classical Greek and Roman Representations

In ancient Greek art, Orpheus frequently appears in vase paintings from the 5th century BCE, often depicted as a musician enchanting animals or navigating the Underworld in scenes tied to his mythological descent for Eurydice. A notable example is an Attic red-figure bell-krater from around 440 BCE, showing Orpheus seated among Thracians, playing his lyre while surrounded by attentive figures, emphasizing his role as a civilizing force through music.[36] Similarly, a hydria attributed to the Orpheus Painter, dated to circa 450 BCE, illustrates Orpheus charming beasts in a serene landscape, highlighting the transformative power of his song in early classical iconography.[37] These red-figure vessels, produced in Athens, reflect Orpheus's integration into broader heroic narratives, portraying him in pastoral or mythical contexts.[38] Roman adaptations extended these visual traditions into mosaics and sculptures, particularly in funerary and domestic settings. In Pompeii's House of Orpheus (VI.14.20), a 1st-century CE mosaic depicts Orpheus centrally positioned with his lyre, surrounded by wild animals like lions and elephants drawn to his music, symbolizing harmony and dominion over nature. Such mosaics, common in elite villas, often placed Orpheus in triclinia or atria to evoke cultural sophistication, incorporating tesserae for vivid color.[39] Apulian red-figure volute kraters from South Italy, dating to the 4th century BCE, further illustrate Orpheus in Underworld scenes, pleading before Hades and Persephone, blending Greek motifs with local funerary customs.[40] Literary representations in classical texts underscore Orpheus's prowess as a poet-musician. In Homer's Iliad (Book 18, lines 569–570), Orpheus is briefly invoked as the son of Oeagrus, a renowned singer whose lyre accompanies heroic gatherings, establishing his archetype in epic poetry.[41] The Odyssey alludes to him indirectly through shades of musicians in the Underworld (Book 11), evoking illusions of his katabasis and the soul's journey. Pindar references Orpheus in Olympian 7 and Pythian 4, portraying him as a divine bard descended from Apollo, whose songs initiate cosmic order and bridge mortal and divine realms.[42] Roman authors amplified these themes with emotional depth. Virgil's Georgics (Book 4, lines 453–527) narrates the Eurydice episode as an epyllion, where Orpheus's lyre sways infernal rulers, but his fateful glance back underscores human frailty and loss, framed within agricultural metaphors.[43] Ovid's Metamorphoses (Books 10–11) expands this into a poignant tale of love and transformation, detailing Orpheus's descent, his songs of pathos that soften Pluto and Proserpina, and his subsequent misogynistic songs leading to his dismemberment by Maenads, emphasizing music's dual power to heal and provoke.[44] Orpheus's imagery held profound symbolic value in Greek and Roman funerary art, representing hope for reunion and transcendence beyond death. On Apulian vases and Roman sarcophagi, his Underworld lyre-playing signifies safe passage for the deceased, with scenes often juxtaposing him with Hermes Psychopompos to evoke the soul's redemption.[40] Limestone reliefs, such as a 2nd-century CE fragment from the Metropolitan Museum, show Orpheus standing with a lyre, symbolizing eternal harmony amid the journey to the afterlife.[45] These motifs, prevalent from the 5th century BCE to the 2nd century CE, offered consolation, transforming personal grief into a universal promise of musical immortality.[46]Medieval and Renaissance Interpretations

In the medieval Christian tradition, Orpheus was frequently interpreted as a prefiguration of Christ, with his descent into Hades to retrieve Eurydice mirroring the Harrowing of Hell, where Christ liberates souls from the underworld. This allegorical reading, prominent among 12th-century exegetes such as Honorius Augustodunensis, portrayed Orpheus's lyre as a symbol of divine harmony that subdued chaos, akin to Christ's redemptive power over sin and death.[47] Such interpretations integrated pagan mythology into Christian theology, emphasizing Orpheus's role as a virtuous pagan prophet whose actions foreshadowed salvation.[48] Boethius further developed this allegorical framework in his Consolation of Philosophy (c. 524 CE), where the Orpheus myth symbolizes the soul's ascent toward the divine, disrupted by a backward glance representing attachment to earthly desires. Orpheus here embodies the philosopher's pursuit of eternal truth, with his music evoking the harmony of the spheres—a cosmic order governed by rational proportions that reflects divine providence.[49] Dante Alighieri extended these ideas in the Divine Comedy (c. 1320), placing Orpheus in Limbo among noble pagans and using his journey as a metaphor for the redemptive force of divine love, which guides the soul through infernal trials toward celestial union.[50] The Renaissance revived Orpheus as a humanist ideal, celebrating his poetic and musical talents as embodiments of intellectual and artistic excellence. Angelo Poliziano's Fabula di Orfeo (1480), a vernacular dramatic eclogue performed at the Medici court, reimagines the myth to highlight Orpheus as the enlightened poet who civilizes nature through eloquence, aligning with Renaissance aspirations to recover classical wisdom.[51] In visual arts, Michelangelo's chalk drawing Orpheus between Life and Death (c. 1530s) blends motifs, portraying Orpheus as a contemplative figure torn between earthly passion and spiritual transcendence, reflecting the artist's own synthesis of antique sculpture and biblical inspiration.[52] Orpheus's influence permeated Renaissance moral philosophy and emblematic literature, where his lyre taming wild beasts illustrated music's civilizing force against barbarism. In Andrea Alciato's Emblematum Liber (1531), emblems featuring Orpheus underscore ethical lessons on harmony and restraint, portraying him as a moral exemplar who elevates society through rational discourse and artistic persuasion. This motif reinforced humanist beliefs in education and culture as agents of ethical transformation.[53]Modern Cultural Influence

Literature and Poetry

In the early 20th century, Rainer Maria Rilke's Sonnets to Orpheus (1922) reimagines the myth as a meditation on fragmentation, transformation, and the creative act, portraying Orpheus as a figure who bridges life and death through song while grappling with loss and renewal.[54] Written in a burst of inspiration, the collection uses the Orphic narrative to explore existential themes, emphasizing the poet's role in weaving disparate elements into wholeness.[55] Similarly, Jean Cocteau's Orphée (1925 play, later adapted), part of his broader Orphic explorations, delves into the artist's descent into otherworldly realms, symbolizing the tension between inspiration and mortality in modern poetic identity.[56] Twentieth-century literature continued to draw on Orpheus through retellings of classical sources, such as Mary Zimmerman's Metamorphoses (1996 premiere, 1998 publication), a theatrical adaptation of Ovid that interweaves the Orpheus and Eurydice story with other myths to examine love, grief, and metamorphosis in a contemporary lens.[57] Margaret Atwood's poetic engagements, including "Orpheus (1)," "Eurydice," and "Orpheus (2)" from her collections like Selected Poems II: 1976-1986 (1986), shift focus to psychological depth, portraying Orpheus's gaze as a possessive force and Eurydice's voice as one of quiet resistance against patriarchal narratives of rescue.[58] Feminist reinterpretations in late 20th- and early 21st-century works highlight themes of gender, loss, and artistry by centering Eurydice's agency, as seen in Sarah Ruhl's Eurydice (2003), a play that reverses the myth to follow Eurydice's underworld experience, her forgetting and rediscovery of self, and the limitations of Orpheus's artistic heroism in the face of emotional disconnection.[59] This perspective critiques traditional tellings by emphasizing female autonomy and the burdens of male-centered creativity. More recent young adult literature, such as Lilliam Rivera's Never Look Back (2020), reimagines the myth in a modern Latinx context in the Bronx, where Eurydice navigates gang pressures and Orpheus's music offers escape, exploring themes of immigration, identity, and toxic relationships.[60] In contemporary fiction, Salman Rushdie's The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999) parallels the Orpheus myth with the lives of rock musicians Vina Apsara and Ormus Cama, transposing the descent into the underworld to a modern tale of fame, exile, and cultural rupture, where music becomes a conduit for crossing boundaries between worlds.[61]Music and Opera

Claudio Monteverdi's L'Orfeo, premiered in 1607, is widely regarded as the first major opera and a foundational work in the genre, directly adapting the Orpheus myth through a prologue and five acts that trace Orpheus's marriage to Eurydice, her death, his descent to the underworld, and ultimate failure to retrieve her.[62] The opera innovatively combines recitative, arias, and choruses to evoke the emotional depth of the legend, emphasizing music's power to move gods and mortals alike.[63] In the Baroque and Classical eras, composers continued to explore the myth's dramatic potential with a focus on emotional expression. Christoph Willibald Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice, first performed in 1762, reformed opera by prioritizing simplicity and naturalness, embodying emotional restraint to heighten the pathos of Orpheus's journey and loss.[64] This work, with its streamlined libretto and innovative use of dance, influenced subsequent reform operas by underscoring the myth's themes of love, grief, and restraint.[65] Joseph Haydn's L'anima del filosofo, ossia Orfeo ed Euridice, composed in 1791 but not premiered until after his death, presents a darker, more philosophical take on the story, incorporating larger choral forces inspired by English oratorio traditions to depict Orpheus's moral and emotional turmoil.[66][67] The 20th century saw Orpheus reimagined in diverse musical forms, blending neoclassicism and modernism. Igor Stravinsky's Orpheus (1947), a ballet score in three scenes, evokes the myth through sparse, elegiac instrumentation, capturing Orpheus's lament and descent with haunting lyricism for strings.[68] Philip Glass's Orphée (1993), a chamber opera in two acts, adapts Jean Cocteau's 1950 film in a minimalist style, using repetitive motifs and pulsing rhythms to explore themes of artistic obsession and mortality within the Orphic narrative.[69][70] In popular music, the Orpheus myth has inspired songs symbolizing artistic descent into personal or creative depths. Sara Bareilles's "Orpheus" (2019), from her album Amidst the Chaos, portrays the legend as a metaphor for enduring love amid grief, with lyrics invoking Orpheus's futile gaze backward to reflect on loss and resilience.[71] Similarly, Arcade Fire's "It's Never Over (Oh Orpheus)" (2010), from The Suburbs, uses the myth to address themes of inescapable regret and cyclical struggle in modern life, layering orchestral swells with urgent vocals to evoke Orpheus's eternal return.[72]Film, Theater, and Visual Media