Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Signified and signifier

View on WikipediaThis article may be too technical for most readers to understand. (September 2022) |

| Semiotics |

|---|

| General concepts |

| Fields |

| Applications |

| Methods |

| Semioticians |

|

| Related topics |

In semiotics, signified and signifier (French: signifié and signifiant) are the two main components of a sign, where signified is what the sign represents or refers to, known as the "plane of content", and signifier which is the "plane of expression" or the observable aspects of the sign itself. The idea was first proposed in the work of Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, one of the two founders of semiotics.

Concept of signs

[edit]The concept of signs has been around for a long time, having been studied by many classic philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, William of Ockham, and Francis Bacon, among others.[1] The term semiotics derives from the Greek root seme, as in semeiotikos (an 'interpreter of signs').[2]: 4 It was not until the early part of the 20th century, however, that Saussure and American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce brought the term into more common use.[3]

While both Saussure and Peirce contributed greatly to the concept of signs, it is important to note that each differed in their approach to the study. It was Saussure who created the terms signifier and signified in order to break down what a sign was. He diverged from the previous studies on language as he focused on the present in relation to the act of communication, rather than the history and development of words and language over time.[3]

Succeeding these founders were numerous philosophers and linguists who defined themselves as semioticians. These semioticians have each brought their own concerns to the study of signs. Umberto Eco (1976), a distinguished Italian semiotician, came to the conclusion that "if signs can be used to tell the truth, they can also be used to lie."[2]: 14 Postmodernist social theorist Jean Baudrillard spoke of hyperreality, referring to a copy becoming more real than reality, the signifier becoming more important than the signified.[4] French semiotician Roland Barthes used signs to explain the concept of connotation—cultural meanings attached to words—and denotation—literal or explicit meanings of words.[2] Without Saussure's breakdown of signs into signified and signifier, however, these semioticians would not have had anything to base their concepts on.

Relation between signifier and signified

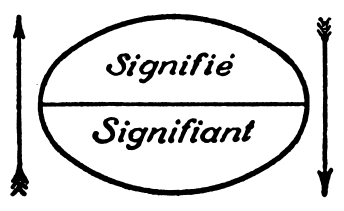

[edit]Saussure, in his 1916 Course in General Linguistics, divides the sign into two distinct components: the signifier ('sound-image') and the signified ('concept').[2]: 2 For Saussure, the signified and signifier are purely psychological: they are form rather than substance.[5]: 22

Today, the signifier is often interpreted as the conceptual material form, i.e. something which can be seen, heard, touched, smelled or tasted; and the signified as the conceptual ideal form.[6]: 14 In other words, "contemporary commentators tend to describe the signifier as the form that the sign takes and the signified as the concept to which it refers."[7] The relationship between the signifier and signified is an arbitrary relationship: "there is no logical connection" between them.[2]: 9 This differs from a symbol, which is "never wholly arbitrary."[2]: 9 The idea that both the signifier and the signified are inseparable is explained by Saussure's diagram, which shows how both components coincide to create the sign.

In order to understand how the signifier and signified relate to each other, one must be able to interpret signs. "The only reason that the signifier does entail the signified is because there is a conventional relationship at play."[8]: 4 That is, a sign can only be understood when the relationship between the two components that make up the sign are agreed upon. Saussure argued that the meaning of a sign "depends on its relation to other words within the system;" for example, to understand an individual word such as "tree," one must also understand the word "bush" and how the two relate to each other.[7]

It is this difference from other signs that allows the possibility of a speech community.[8]: 4 However, we need to remember that signifiers and their significance change all the time, becoming "dated." It is in this way that we are all "practicing semioticians who pay a great deal of attention to signs … even though we may never have heard them before."[2]: 10 Moreover, while words are the most familiar form signs take, they stand for many things within life, such as advertisement, objects, body language, music, and so on. Therefore, the use of signs, and the two components that make up a sign, can be and are—whether consciously or not—applied to everyday life.

Depth psychology and philosophy

[edit]| Part of a series of articles on |

| Psychoanalysis |

|---|

|

Lacanianism

[edit]Jacques Lacan presented formulas for the ideas of the signified and the signifier in his texts and seminars, specifically repurposing Freud's ideas to describe the roles that the signified and the signifier serve as follows:

There is a 'barrier' of repression between Signifiers (the unconscious mind: 'discourse of the Other') and the signified […] a 'chain' of signifiers is analogous to the 'rings of a necklace that is a ring in another necklace made of rings' […] 'The signifier is that which represents a subject (fantasy-construct) for another signifier'.[9][10][11]

— Lacan, paraphrased

Floating signifier

[edit]Originating in an idea from Lévi-Strauss, the concept of floating signifiers, or empty signifiers, has since been repurposed in Lacanian theory as the concept of signifiers that are not linked to tangible things by any specific reference for them, and are "floating" or "empty" because of this separation. Slavoj Žižek defines this in The Sublime Object of Ideology as follows:

[T]he multitude of 'floating signifiers' […] is structured into a unified field through the intervention of a certain 'nodal point' (Lacanian point de capiton) which 'quilts' them [to] […] the 'rigid designator', which totalizes an ideology by bringing to a halt the metonymic sliding of its signified […] it is a signifier without the signified'.[12]

Signified

[edit]The signified is [an untranslatable, atmospheric irreducibility of the-chain-of-signifiers-abstracted]; the disclosed barrier (between the-chain-of-signifiers qua signified) is a metaphor-repression-transference journey through place.[20]

Schizoanalysis

[edit]In their theory of schizoanalysis, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari made radical uses of the ideas of the signified and the signifier following Lacan. In A Thousand Plateaus, extending from their ideas of deterritorialization and reterritorialization, they developed the idea of "faciality" to refer to the interplay of signifiers in the process of subjectification and the production of subjectivity. The "face" in faciality is a system that "brings together a despotic wall of interconnected signifiers and passional black holes of subjective absorption".[21] Black holes, fixed on white walls which antagonized flows bounce off of, are the active destruction, or deterritorialization, of signs.[22] What makes the power exerted by the face of a subject possible is that, creating an intense initial confusion of meaning, it continues to signify through its persistent refusal to signify.[23]

Significance is never without a white wall upon which it inscribes its signs and redundancies. Subjectification is never without a black hole in which it lodges its consciousness, passion, and redundancies. Since all semiotics are mixed and strata come at least in twos, it should come as no surprise that a very special mechanism is situated at their intersection. Oddly enough, it is a face: the white wall/black hole system. […] The gaze is but secondary in relation to the gazeless eyes, to the black hole of faciality. The mirror is but secondary in relation to the white wall of faciality.[24]

What distinguishes this radical use and systemization of the signified and the signifier as interplaying in subjectivity from Lacan and Sartre as well as their philosophical predecessors in general is that, beyond a resolution with the oppressive forces of faciality and the dominance of the face, Deleuze and Guattari reproach the preservation of the face as a system of a tight regulation of signifiers and destruction of signs, declaring that "if human beings have a destiny, it is rather to escape the face, to dismantle the face and facializations".[25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (March 2025) |

- ^ Kalelioğlu, Murat (2018). A Literary Semiotics Approach to the Semantic Universe of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-1527520189.

- ^ a b c d e f g Berger, Arthur Asa. 2012. Media Analysis Techniques. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

- ^ a b Davis, Meredith; Hunt, Jamer (2017). Visual Communication Design: An Introduction to Design Concepts in Everyday Experience. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 135. ISBN 9781474221573.

- ^ Berger, Arthur Asa (2005). Media Analysis Techniques, Third Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. p. 14. ISBN 1412906830.

- ^ Berger, Arthur Asa. 2013. "Semiotics and Society." Soc 51(1):22–26.

- ^ Chandler, Daniel. 2017. Semiotics: The Basics. New York: Routledge.

- ^ a b Chandler, 2002, p. 18.

- ^ a b Cobley, Paul and Litza, Jansz. 1997. Introducing Semiotics, Maryland: National Bookworm Inc.

- ^ Smith, Joseph H.; Kerrigan, William, eds. (1983). Interpreting Lacan. Psychiatry and the Humanities. Vol. 6. Yale University Press. pp. 54, 168, 173, 199, 202, 219. ISBN 978-0-300-13581-7.

- ^ Bailly, Lionel (2020). "Real, Symbolic, Imaginary". Lacan: A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld Beginner’s Guides. Oneworld. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-85168-637-7.

For Lacan, there are no signifieds in the unconscious, only signifiers.

- ^ Boothby, Richard (2001). Freud as Philosopher: metapsychology after Lacan. Routledge. pp. 13, 14. ISBN 0-415-92590-8.

The Lacanian subject is 'strung along' by the unfolding of the chain of signifiers; its very being is conditioned by the organization of a linguistic code. ... For Lacan, the unconscious is 'the discourse of the Other.' Human desire is 'the desire of the Other.'

- ^ Žižek, Slavoj (1989). "Part II: Lack in the Other; Che Vuoi?". The Sublime Object of Ideology. Verso. pp. 95, 109. ISBN 978-1-84467-300-1.

- ^ Barthes, Roland; Duisit, Lionel (1975). "An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative". New Literary History. 6 (2): 237–272. doi:10.2307/468419. JSTOR 468419. Retrieved 2022-01-18.

A lyrical poem, for instance, is a vast metaphor possessing a single signified; to sum it up means to reveal the signified, an operation so drastic that it causes the identity of the poem to evaporate[.]

- ^ Deleuze, Gilles; Guattari, Félix (1987). "587 B.C.-A.D. 70: On Several Regimes of Signs". A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Massumi, Brian. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 112, 114. ISBN 978-1-85168-637-7.

It is this amorphous ['atmospheric'] continuum that for the moment plays the role of the 'signified,' but it continually glides beneath the signifier, for which it serves only as a medium or wall; the specific forms of all contents dissolve in it. The atmospherization or mundanization of contents. Contents are abstracted. ... The signified constantly reimparts signifier, recharges it or produces more of it. The form always comes from the signifier. The ultimate signified is therefore the signifier itself, in its redundancy or 'excess.' ... communication and interpretation are what always serve to reproduce and produce signifier[s].

- ^ Ricoeur, Paul (1970). "Book III: Dialectic: A Philosophical Interpretation of Freud: 1. Epistemology: Between Psychology and Phenomenology: Psychoanalysis is not Phenomenology". Terry Lectures: Freud & Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation. Translated by Savage, Denis. Yale University Press. p. 402. ISBN 978-0-300-02189-9.

[Leplanche and Leclaire] use the bar to express the double nature of repression: it is a barrier that separates the systems, and a relating that ties together the relations of signifier to signified...Metaphor is nothing other than repression, and vice versa[.]

- ^ Morris, Humphrey (1980). "The Need to Connect: Representations of Freud's Psychical Apparatus". In Smith, Joseph H. (ed.). The Literary Freud: Mechanisms of Defense and the Poetic Will. Psychiatry and the Humanities. Vol. 4. Yale University Press. p. 312. ISBN 0-300-02405-3.

Übertragen and metapherein are synonyms, both meaning to transfer, to carry over or beyond, and I. A. Richards pointed out a long time ago in The Philosophy of Rhetoric that what psychoanalysts call transference is another name for metaphor.

- ^ Fouad, Jehan Farouk; Alwakeel, Saeed (2013). "Representations of the Desert in Silko's 'Ceremony' and Al-Koni's 'The Bleeding of the Stone'". Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics. 33 (The Desert: Human Geography and Symbolic Economy): 36–62. JSTOR 24487181. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

The connection between 'place' and 'metaphor' is evident. Paul Ricœur remarks that 'as figure, metaphor constitutes a displacement and an extension of the meaning of words; its explanation is grounded in the theory of substitution ' (The Rule of Metaphor 3; italics added).

- ^ Cambray, Joseph; Carter, Linda (2004). "Analytic methods revisited". Analytical Psychology: Contemporary Perspectives in Jungian Analysis. Advancing Theory in Therapy. Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-58391-999-6.

Metaphors in analysis are woven into narratives, which offer a creative domain for playful interaction and allow multiple strands of life to be interwoven. Psychoanalyst Arnold Modell (1997) argues that linguists, neurobiologists, and psychoanalysts can share a common paradigm through metaphor.

- ^ Guattari, Félix (2011) [1979]. The Machinic Unconscious: Essays in Schizoanalysis. Semiotext(e) Foreign Agents Series. Translated by Adkins, Taylor. Semiotext(e). p. 338. ISBN 978-1-58435-088-0.

Paul Ricoeur [states...'T]hus, the signified is untranslatable[.']...From 'Signe et Sens,' Encyclopedia Universalis, 1975.

- ^ [13][14][15][16][17][18][19]

- ^ Bogue, Ronald (2003). Deleuze on Music, Painting and the Arts. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-415-96608-5.

- ^ Morrione, Deems D. (2006). "When Signifiers Collide: Doubling, Semiotic Black Holes, and the Destructive Remainder of the American Un/Real". Cultural Critique (63): 157–173. JSTOR 4489250. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

The semiotic black hole is...the destruction of the whole sign...that radically transforms the socius, possessing a gravitational pull that has the power to massively reshape and remotivate ... the semiotic black hole...[leaves] little or no trace of its influence. ... a collision of a fatal event and a perfect object[.] ... Temporality is constant motion; to mark a point in time is to freeze only that moment, to celebrate impression and deny expression.

- ^ Gilbert-Rolfe, Jeremy (1997). "Blankness as a Signifier". Critical Inquiry. 24 (1): 159–175. doi:10.1086/448870. JSTOR 1344162. S2CID 161209057. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

The face signifies by refusing to signify. ... [Deleuze's] Bergsonianism...predicated on the idea of the surface—the plane and the point—as opposed to the form—the shape and its interior. ... The passage from Victorian horror vacui to the present is that passage, the passage from potentiality to instantaneity. If in the former blankness was not a sign, but rather the place for the sign, in the latter it has become signally characteristic of the surface of all the signs which exclude it with recognizability and narrative...[l]ying outside of art it would have to be art's subject.

- ^ Deleuze, Gilles; Guattari, Félix (1987). "Year Zero: Faciality". A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Massumi, Brian. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 167, 171. ISBN 978-1-85168-637-7.

- ^ ibid., pp. 171.

Sources

[edit]- Ferdinand de Saussure (1959). Course in General Linguistics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

External links

[edit]Signified and signifier

View on GrokipediaOrigins in Semiotics

Ferdinand de Saussure's Course in General Linguistics

The Course in General Linguistics (Cours de linguistique générale), published in 1916, consists of notes compiled by Ferdinand de Saussure's students Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye from lectures delivered at the University of Geneva between 1906 and 1911.[2] In this work, Saussure formulates the linguistic sign as a two-sided psychological entity, comprising the signifier (signifiant) and the signified (signifié), marking a foundational shift in understanding language as a system of arbitrary relations rather than direct naming of objects.[1] This dyadic model posits that signs do not link words to things but unite a sensory form with a conceptual content within the mind.[8] The signifier refers to the acoustic image, defined as the imprint of the sound pattern in the speaker's psyche, such as the sequence of sounds forming the word "tree" without regard to its physical utterance.[1] For instance, Saussure illustrates this with the French term arbre, where the signifier is the mental trace of its phonetic form. The signified, conversely, is the concept or idea evoked, like the abstract notion of a tree, independent of any specific sensory perception of actual trees.[9] This distinction underscores that linguistic value arises from the association within the sign itself, not from extrinsic references.[8] Saussure advocates a synchronic approach to linguistics, prioritizing the study of language as a functional system at a single point in time over diachronic analysis of its historical changes.[2] He proposes linguistics as the central discipline within semiology, a broader science of signs embedded in social phenomena, arguing that understanding sign systems requires examining their internal structures and relational differences.[1] This framework laid the groundwork for structural linguistics by treating language as a self-contained entity governed by conventions.[10]Historical Precursors and Influences

The concept of distinguishing between a sign's form and its conceptual content traces back to ancient Greek philosophy, where debates on the nature of language anticipated key elements of later semiotic theory. In Plato's Cratylus (circa 360 BCE), the dialogue examines whether names inherently mimic the essence of things (a "natural" view advocated by Cratylus) or arise from social convention (as argued by Hermogenes and ultimately favored by Socrates), highlighting an early tension between motivation and arbitrariness in signification without formalizing a dyadic structure.[11] Aristotle, in On Interpretation (circa 350 BCE), advanced this by positing that spoken words serve as "symbols" or signs of "affections" or impressions in the soul, which themselves are likenesses of actual things in the world, thus introducing a rudimentary separation between the audible signifier and the mental signified while maintaining a referential link to external reality.[12] These ancient ideas influenced subsequent Western thought on signs, particularly through empiricist philosophy in the early modern period. John Locke, in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690, Book III), described words as arbitrary signs standing for ideas in the mind rather than directly for objects, emphasizing their role in communication while critiquing inadequate signification that leads to philosophical error; this instrumental view of signs as conveyors of internal concepts prefigured semiotic doctrines but retained a triadic orientation toward referents, differing from purely relational models. Locke's coinage of "semiotike" as the doctrine of signs in 1690 further established the field, bridging philosophy and emerging linguistics. In the 19th century, comparative linguistics provided methodological precursors amid a shift toward systematic language study. August Schleicher, in his Compendium of the Comparative Grammar of the Indo-European, Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin Languages (1861), treated languages as evolving organisms amenable to reconstruction via sound correspondences, influencing Saussure's early training in historical philology; however, Schleicher's focus on diachronic evolution and external genetic classification contrasted with the emphasis on synchronic, internal sign relations that marked Saussure's departure.[13] This progression from referential and historical frameworks culminated in Saussure's innovation of prioritizing the dyadic bond within the sign itself, detached from direct object-reference, as a self-contained system of differences.[14]Fundamental Definitions

The Dyadic Sign: Signifier and Signified

In Ferdinand de Saussure's framework, as outlined in his Course in General Linguistics compiled from lectures delivered between 1906 and 1911, the linguistic sign is conceived as a dyadic entity comprising two indissociable elements: the signifier and the signified.[2] The signifier refers to the perceptual or material form of the sign, such as the sequence of sounds in spoken language (the "sound-image" or image acoustique) or the visual marks in written language, representing the sensible aspect that enters consciousness through sensory channels.[1] This form is not the physical sound waves or ink on paper but the mental impression they evoke, emphasizing its psychological rather than material nature.[3] The signified, by contrast, denotes the conceptual content or mental idea associated with the signifier, constituting the "plane of content" within the sign.[15] It is the abstract notion or image of the thing evoked by the signifier, such as the idea of a tree rather than any specific empirical tree.[9] Saussure stresses that the signifier and signified are like the two sides of a single sheet of paper, inherently linked yet analytically distinguishable; their union forms the complete sign, which exists solely in the social realm of language as a system of differences.[1] This dyadic model abstracts the sign from direct reference to external reality, focusing instead on the internal relations within language itself, where meaning arises from oppositions rather than resemblance to objects.[3] For instance, the French word ouvrir, pronounced as a sequence of phonetic elements, serves as the signifier that evokes the signified concept of the action of opening—such as parting doors or lids—without any intrinsic or natural connection between the auditory form and the idea.[16] Similarly, the English term "tree" functions as a signifier triggering the mental image of an arboreal form, independent of any particular tree in the physical world; the sign's value derives from its differentiation from other signs like "bush" or "flower" within the linguistic system.[9] This separation underscores Saussure's view that signs operate in a closed, self-referential domain, prioritizing systemic structure over empirical correspondence.[1]Arbitrariness and Conventionality

Ferdinand de Saussure posited the arbitrariness of the linguistic sign as a foundational principle, asserting that the bond between the signifier—a sound-image or form—and the signified—the concept it represents—is not determined by any natural or intrinsic necessity.[1] This arbitrariness implies that the choice of a particular signifier to denote a given signified lacks motivation from the properties of either element, rendering the association contingent rather than inherent.[17] Saussure emphasized that "the linguistic sign is arbitrary," underscoring that language operates without reliance on pre-existing resemblances or causal links between form and meaning.[1] Cross-linguistic variations exemplify this principle: the English signifier "dog" links to the signified concept of a domesticated canine, while French employs "chien" and German "Hund" for the identical notion, demonstrating that no universal phonetic form corresponds naturally to the idea.[18] Similarly, Saussure illustrated with "sister," noting its arbitrary linkage to the French sequence s-o-r, which could equally attach to s-i-s-t-e-r in English without altering the signified.[19] These differences arise not from the essence of the concepts but from historical and systemic contingencies within each language, challenging assumptions of mimetic representation where words echo the objects or ideas they denote.[4] The conventionality of signs stems from their establishment and maintenance through collective social agreement within a speech community, where meaning persists via habitual usage rather than individual invention or fixed essence.[19] Saussure argued that linguistic expression relies on "collective behavior or...convention," enabling the system's coherence while permitting evolution through communal shifts, such as lexical innovations or borrowings.[1] This social foundation positions language as an autonomous, self-regulating entity, insulated from external referents, wherein systemic interdependencies among signs—rather than isolated links to reality—govern functionality and variation across idioms.[11]Relationship Dynamics

The Arbitrary Bond Between Signifier and Signified

In Ferdinand de Saussure's framework, the bond linking the signifier—the acoustic image or form—and the signified—the conceptual content—is fundamentally arbitrary, lacking any necessary or innate correspondence between the two.[3] This arbitrariness posits that the association arises not from resemblance or causation but from collective habit and social convention within a linguistic community.[2] The union forms a single, indissoluble entity, the sign, yet remains asymmetrical in evocation: the signifier typically prompts the signified through repeated usage, while the reverse lacks direct efficacy outside the systemic context.[20] The linkage is inherently psychological, residing in the associative faculties of speakers rather than referencing external objects or realities.[2] Meaning emerges relationally from contrasts within the language system, known as langue—the abstract, collective structure of signs—rather than from isolated denotation.[21] For instance, the French words chat (cat) and chapeau (hat) derive their distinct values not from inherent properties but from minimal phonetic differences (*ch- vs. *ch- with vowel shift) and oppositional positioning against other terms like chien (dog), illustrating how signification depends on systemic differentials rather than substantive links to the world.[2] This relationality operates primarily in langue, the normative code shared socially, distinct from parole, the individualized acts of speech where variations occur but do not alter core associations.[21] Saussure maintains that no sign directly mirrors or refers to extralinguistic reality; instead, the signified is a mental construct delimited by linguistic boundaries, precluding unmediated access to things-in-themselves.[20] Even apparent motivations, such as onomatopoeic words imitating sounds (e.g., bang for an explosion), fail to constitute exceptions, as these are stylized and conventionalized within the language's phonological inventory, varying cross-linguistically—English meow for a cat versus French miaou—and thus subordinated to arbitrary systemic constraints rather than pure imitation.[22] This reinforces the bond's conventional character, immune to claims of natural necessity.[23]Instances of Motivation and Iconicity

Saussure recognized that while the linguistic sign is fundamentally arbitrary, instances of relative motivation exist within language systems, where the connection between signifier and signified arises not from direct resemblance but from internal linguistic relations such as compositionality or analogy.[24] Relative motivation operates through syntagmatic and paradigmatic associations, as seen in compound forms like the French word dix-neuf ("nineteen"), which motivates its form by combining the signifiers dix ("ten") and neuf ("nine"), both of which are individually arbitrary but yield a partially predictable whole within the system's conventions.[22] Similarly, derivational morphology provides relative motivation, as in philosophie deriving from philosophe via suffixation, linking form to conceptual extension without absolute necessity.[4] These cases of relative motivation do not challenge the overarching arbitrariness of the sign, as they depend on pre-existing arbitrary elements within the language, forming a chain of conventions rather than inherent links to the signified.[25] Saussure emphasized that no language lacks some degree of such motivation, yet it remains subordinate to the system's arbitrary foundation, ensuring linguistic flexibility and historical change.[24] Iconicity, involving direct perceptual resemblance between signifier and signified, appears marginally in language through onomatopoeia, where words imitate sounds, such as English meow for a cat's cry.[26] However, Saussure subordinated these to arbitrariness, noting cross-linguistic variations—like German miau or French miaou—demonstrate cultural and phonetic shaping over natural mimicry, rendering even onomatopoeic forms conventionally arbitrary rather than universally motivated.[27] Beyond language proper, purely iconic signs occur in non-linguistic domains, such as diagrams where spatial arrangement mirrors conceptual relations, but Saussure viewed these as extrinsic to the linguistic sign's dyadic structure.[28] Thus, iconicity supplements rather than supplants the arbitrary bond, preserving the sign's systemic conventionality.[29]Philosophical and Theoretical Extensions

Structuralism and Post-Structuralism

Structuralism adapted Ferdinand de Saussure's dyadic model of the sign to interpret cultural and social systems as underlying structures of interrelated signs, often organized through binary oppositions that generate meaning. Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, in his 1958 book Structural Anthropology, analyzed myths across cultures by identifying invariant binary structures, such as nature versus culture or raw versus cooked, which he posited as universal cognitive frameworks underlying diverse narratives.[30] This approach treated myths not as historical accounts but as semiotic systems where signifiers and signifieds form oppositional networks revealing deep cultural logics. Literary theorist Roland Barthes extended this framework in his 1957 Mythologies, conceptualizing contemporary cultural artifacts like advertisements and wrestling as second-order semiotic systems. In these, the full sign from Saussure's primary dyad serves as the signifier for a mythical signified, masking ideological content under the guise of naturalness—for instance, a Black soldier saluting the French flag as a signifier of false imperial harmony.[30] Barthes' method decoded how such signs perpetuate bourgeois myths by emptying historical signifieds of contingency, enabling a systemic critique of ideology through the interplay of signifiers and signifieds.[31] Post-structuralism, emerging in the late 1960s, challenged the structuralist presumption of stable signifieds tied to fixed structures, emphasizing instead the instability and relational deferral of meaning. Philosopher Jacques Derrida, in his 1967 Of Grammatology, critiqued Saussure's model by introducing différance—a neologism blending difference and deferral—to argue that signification relies on endless chains of differing signifiers without a ultimate signified anchor, rendering meaning perpetually postponed and context-dependent.[32] This deconstructive strategy influenced literary criticism by dismantling binary oppositions as hierarchical illusions, promoting readings that trace textual traces and absences rather than coherent wholes.[33] The dyad's extension in these movements facilitated applications in literary analysis, where structuralism sought universal patterns akin to linguistic grammars, while post-structuralism's focus on deferral encouraged interpretive multiplicity that often dissolved referential stability into flux, impacting fields like cultural studies through deconstructive practices.[30]Psychoanalytic Interpretations

Jacques Lacan reinterpreted Saussure's dyadic model by inverting its priorities, emphasizing the dominance of the signifier over the signified in psychic processes. In Lacanian theory, the unconscious operates through chains of signifiers that represent the subject for one another, rather than stable links to signified concepts, reflecting Freudian primary processes as senseless enchainings.[34] Lacan famously asserted that "the unconscious is structured like a language," positioning signifiers as the fundamental weave of the psyche, detached from Saussure's balanced dyad where the signified holds conceptual precedence.[35][36] The signified in this framework appears elusive or "barred," denoted as , symbolizing a fundamental lack or absence that drives desire, with meaning sliding along signifier chains without fixed anchorage. The phallus functions as a privileged "master signifier," an empty or unary term that orients the symbolic order but signifies nothing in itself, instead structuring lack and difference across the psyche.[34][37] Such floating or master signifiers, like the phallus, acquire contingent content through ideological or desirous investments, inverting Saussure's arbitrariness into a metaphoric and metonymic play where the signified perpetually defers. These constructs, while influential in clinical psychoanalysis, prioritize interpretive speculation over empirical linguistic data, aligning with broader critiques of Freudian models for lacking falsifiable predictions in cognitive science.[34] In contrast, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari's schizoanalysis, developed in works like Anti-Oedipus (1972), rejects Lacanian Oedipal hierarchies and signifier primacy as repressive codings, favoring "rhizomatic" flows of desiring-machines that bypass fixed signifieds for multiplicities of signs in productive assemblages. Schizoanalysis critiques the dyad's retention in Lacan as perpetuating familial triangulation, instead promoting decoding of flows without interpretive centering on barred signifieds or master signifiers, aiming to liberate libido from psychoanalytic structures. This approach, while theoretically provocative, similarly eschews empirical testing, relying on philosophical reconfiguration rather than causal evidence from neurology or developmental psychology.[38][39]Criticisms and Empirical Challenges

Philosophical Objections to Relativism

Saussure's dyadic model of the sign confines meaning to the arbitrary relation between signifier and signified within a self-contained linguistic system, thereby promoting relativism by excluding direct reference to external objects or causal structures in the world.[40] This internalist approach treats the signified as a purely conceptual entity defined relationally through differences from other signs, rather than through correspondence to objective referents. Jacques Derrida extended this framework through deconstruction, rejecting the notion of a "transcendental signified" as an illusory foundation for meaning and emphasizing différance—an endless play of deferral among signifiers without ultimate grounding.[42] Critics argue that this undermines any stable signified, resulting in an infinite regress of traces where meaning perpetually evades fixation, lacking anchor in verifiable reality.[42] Derrida's assertion that "there is nothing outside the text" further detaches signification from empirical reference, rendering truth conditions indeterminate.[42] Philosophers like John Searle charge that such views embody idealism by prioritizing systemic differences over intentional reference to the world, treating language as a closed loop disconnected from causal efficacy.[42] Searle contends this ignores how speech acts derive conditions of satisfaction from real-world states, not mere internal oppositions, thus Saussurean-inspired theories fail to account for language's referential function.[42] This detachment fosters skepticism toward objective truth, privileging cultural constructs over empirical validation. The dyad's relativism contributed to postmodern currents that equate meaning with interpretive contingency, enabling constructivist epistemologies that downplay realist constraints on knowledge.[43] Such positions, by severing signs from worldly causation, undermine pursuits of universal truth claims grounded in observation and logic.[43]Cognitive and Linguistic Counter-Evidence

Embodiment theories in cognitive linguistics challenge the Saussurean claim of arbitrariness by positing that signified concepts are systematically linked to signifiers through sensorimotor grounding in human physiology. George Lakoff's framework of conceptual metaphor theory, elaborated in works from the 1980s onward, demonstrates that linguistic expressions often reflect embodied experiences, such as mapping verticality onto valence (e.g., "happy is up" correlating with postural cues in infants as young as three months).[44] This motivation arises from neural simulations of bodily states during conceptualization, evidenced by fMRI studies showing activation of sensory-motor cortices during abstract metaphor processing, rather than detached symbolic association.[45] Psycholinguistic research further reveals non-arbitrary phonetic-conceptual mappings via priming and sound symbolism effects. In the bouba-kiki paradigm, originally observed by Wolfgang Köhler in 1929 among African populations and replicated cross-culturally, over 90% of participants in diverse language groups (including English, Tamil, and Japanese speakers) pair spiky shapes with high-frequency, plosive sounds ("kiki") and rounded shapes with low-frequency, voiced sounds ("bouba"), suggesting an innate audiovisual congruence independent of learned convention.[46] Semantic priming experiments extend this, showing facilitated lexical access for pseudowords with consistent form-meaning alignments (e.g., rounded vowels evoking softness), with reaction time reductions of 20-50 milliseconds compared to inconsistent pairings, as measured in event-related potentials.[47] Evolutionary perspectives underscore innate constraints on language structure, countering the dyad's emphasis on social convention. Noam Chomsky's universal grammar hypothesis, formalized in 1965, posits a genetically endowed language faculty with parametric settings activated by minimal input, enabling children to converge on recursive syntax across unrelated languages within 3-4 years despite poverty of stimulus (e.g., mastering long-distance dependencies absent in primary data).[48] This biological endowment implies motivated universals, such as hierarchical phrase structure over linear sequencing, evidenced by consistent typological patterns in 7,000+ documented languages, where only a fraction of logically possible grammars occur due to innate biases rather than arbitrary cultural selection.[49]Alternative Frameworks

Peircean Triadism and Realism

Charles Sanders Peirce developed a triadic model of the sign, comprising the representamen (the sign vehicle analogous to a signifier), the object (the real-world referent), and the interpretant (the mental or behavioral effect produced in an interpreter).[50] This structure posits that a sign functions through a triadic relation where the representamen stands for the object only insofar as it generates an interpretant, which itself may become a new representamen in an ongoing process of semiosis.[50] Unlike Saussure's dyadic pairing, which confines meaning to an internal relation between signifier and signified, Peirce's triad incorporates external reference to an independent object, grounding semiosis in reality rather than a closed linguistic system.[51] Peirce's framework emphasizes realism by allowing signs to index actual causal connections in the world, such as smoke serving as an indexical sign of fire through physical contiguity and shared origin, rather than mere convention or arbitrary linkage.[50] Indices, as a class of signs, depend on existential relations to their objects, enabling representation to track verifiable causes without collapsing into subjective projection.[52] This contrasts with dyadic models' tendency toward self-referential loops, where signified concepts lack mandatory anchorage to empirical objects, potentially fostering relativism detached from causal efficacy.[51] The interpretant's role further supports realism, as it evolves through habits of inquiry that test signs against experiential outcomes, aligning interpretation with objective constraints.[50] The triad's advantages lie in its capacity to accommodate truth conditions and pragmatic validation, where successful semiosis correlates with accurate reference to objects, as evidenced in scientific inference where signs predict real effects.[53] Unlimited semiosis—the chain of interpretants—does not devolve into infinite regress because each link remains tethered to the object's dynamical reality, permitting cumulative refinement toward truth.[50] In critiquing dyadic abstraction, Peirce's model avoids insulating signs from falsification, as interpretants must confront the object's resistance to misinterpretation, fostering a semiotics oriented toward empirical adequacy over structural autonomy.[54] This realism underpins Peirce's broader logic of inquiry, where signs mediate between mind and world to yield actionable knowledge.[55]Pragmatic and Biosemiotic Perspectives

Charles Morris, in his 1938 work Foundations of the Theory of Signs, extended semiotic analysis beyond Saussure's dyadic model by incorporating a pragmatic dimension that emphasizes the behavioral context of signs.[56] Morris defined pragmatics as the study of the relation between signs and their interpreters, introducing a triadic structure involving the sign vehicle (analogous to the signifier), the designatum (akin to the signified), and the interpreter who effects a response.[57] This framework, influenced by behaviorism and pragmatism, posits that signs function not in isolation but through their impact on users' actions and orientations, such as in stimulus-response cycles where the signified gains causal efficacy via observable behaviors rather than abstract linguistic convention alone.[58] In contrast to Saussure's emphasis on arbitrary, system-internal relations within human language, Morris's approach critiques the dyad for neglecting the empirical role of interpreters, arguing that semiosis requires accounting for how signs mediate environmental interactions and adaptive responses.[59] For instance, in pragmatic terms, a sign's meaning emerges from its disposition to evoke specific interpretations and uses in context, grounding the signified in verifiable behavioral outcomes rather than purely mental concepts divorced from causation.[60] This triadic extension highlights the limitations of anthropocentric dualism, as it applies to non-linguistic domains where signs influence survival-oriented actions without relying on verbal systems. Biosemiotics further develops this pragmatic grounding by applying sign processes to biological systems, positing that semiosis pervades nature beyond human cognition. Jesper Hoffmeyer, a key proponent since the 1990s, argued in works like Signs of Meaning in the Universe (1996) that living organisms engage in sign interpretation tied to evolutionary fitness, such as alarm pheromones in ants functioning as signifiers whose signified effects—evasive behaviors—directly link to survival probabilities.[61] In this view, the signified is not arbitrarily decoupled but causally anchored in ecological functions, where cellular or organismal responses to molecular signals demonstrate proto-semiosis observable through empirical biology.[62] Hoffmeyer's framework critiques Saussure's dyad as insufficient for non-anthropocentric semiosis, favoring instead models that integrate pragmatic interpretation with biosocial realities, such as animal communication where signals correlate predictably with environmental threats rather than conventional arbitrariness.[63] Empirical studies of phenomena like bee dances or bacterial quorum sensing provide evidence for these sign processes, revealing causal chains from signifier emission to adaptive signified responses that predate and underpin linguistic evolution.[64] This perspective underscores a realist ontology of signs, where biological efficacy trumps abstract dualism, supported by interdisciplinary data from ethology and molecular biology over purely theoretical linguistics.[65]Contemporary Applications and Impact

In Cognitive Science and AI

In cognitive science, the signified-signifier dyad has been adapted within cognitive semiotics to model meaning as emerging from perceptual and conceptual processes, where signifiers arise from sensory inputs and signifieds from internalized categories. This framework intersects with prototype theory, pioneered by Eleanor Rosch in her 1975 study on semantic categories, which demonstrates that human concepts are organized around fuzzy prototypes—central, typical exemplars—rather than rigid definitions, rendering signifieds probabilistic and context-dependent rather than fixed abstractions. Empirical evidence from Rosch's experiments, involving category verification tasks with objects like birds or furniture, showed faster recognition for prototypes (e.g., robin over penguin), supporting graded membership that challenges Saussure's binary linkage by emphasizing experiential variability in signified formation. In artificial intelligence, particularly natural language processing, the dyad informs the mapping of signifiers (text tokens) to signified approximations via embeddings in transformer architectures, introduced by Vaswani et al. in 2017, where attention mechanisms learn contextual relations among words to generate vector representations encoding latent meanings. These models process signifiers sequentially but encounter the symbol grounding problem, formalized by Stevan Harnad in 1990, which posits that purely symbolic systems cannot intrinsically derive meaning without anchoring to non-symbolic, sensorimotor experiences in the environment—mirroring critiques of Saussure's ungrounded dyad in lacking causal ties to referents. Harnad argued for hybrid approaches, combining symbolic manipulation with robotic interaction to ground symbols, a limitation evident in large language models' hallucinations, where ungrounded signifieds produce disconnected outputs despite pattern-matching proficiency. The dyad's limitations in overlooking embodiment— the role of physical interaction in shaping meaning—have prompted shifts toward multimodal AI systems. For instance, OpenAI's CLIP model, released in 2021, trains on 400 million image-text pairs to align visual and linguistic representations, effectively grounding textual signifiers in perceptual signifieds via contrastive learning, enabling zero-shot tasks like image classification from descriptions. This addresses Harnad's grounding challenge by incorporating embodied referents, though empirical evaluations show persistent gaps in abstract or causal reasoning, underscoring the dyad's insufficiency for full semantic realism without broader sensorimotor integration.Cultural and Media Analysis

In Roland Barthes' 1957 collection Mythologies, the signified-signifier dyad is extended to dissect contemporary cultural "myths" as second-order semiotic systems, wherein a primary sign (combining linguistic or visual signifier with its denotative signified) serves as a new signifier for ideological connotations that naturalize dominant social orders. Barthes posits that these myths depoliticize history by presenting contingent bourgeois values as eternal truths; for example, professional wrestling's theatrical excess—marked by wrestlers' prolonged suffering and unambiguous villainy—signifies a spectacle of justice and retribution, evoking collective catharsis while obscuring real-world power imbalances.[66][67] Media studies have similarly employed this framework to unpack advertisements as chains of signifiers evoking desired signifieds, thereby shaping consumer ideologies. A perfume ad's visual signifier of a scantily clad model in an exotic locale connotes signifieds of liberation and sensuality, linking product acquisition to aspirational lifestyles and bypassing rational evaluation of utility. This approach reveals how media manipulates associative links to foster brand loyalty, with empirical studies showing correlations between semiotic cues and increased purchase intent in controlled experiments.[68][69] Critiques highlight how such analyses, prevalent in institutionally left-leaning cultural studies, promote interpretive relativism that detaches from causal evidence, enabling unsubstantiated claims of pervasive ideological manipulation akin to conspiratorial narratives. By treating all media as myth-laden sign systems without falsifiable metrics, these methods risk conflating subjective connotation with objective intent, as seen in overreadings where empirical audience reception data contradicts assumed decodings; for instance, viewer surveys often reveal literal rather than ideological interpretations of ads. This echoes broader concerns that semiotic deconstruction favors hermeneutic skepticism over verifiable mechanisms, potentially amplifying bias toward viewing culture through a lens of perpetual subversion.[70][71]Recent Developments and Debates

In recent years, scholars have explored analogies between Saussurean semiotics and quantum mechanics, positing that meanings can exist in superposition akin to quantum states, where a signifier potentially evokes multiple signifieds until contextual "measurement" resolves ambiguity.[72][73] These proposals, appearing in 2024 publications, draw on principles like Schrödinger's cat to examine the arbitrary link between signifier and signified under quantum uncertainty, but remain largely theoretical without empirical validation in linguistic data.[74] In medical semiotics, post-2000 applications have emphasized causal linkages in diagnostics, treating observable symptoms as signifiers reliably indicating underlying diseases as signifieds through pathophysiological mechanisms rather than arbitrary convention. A 2024 analysis expands this framework to include diverse bodily phenomena as signs, integrating anthropological perspectives on symptom perception while grounding interpretations in clinical causation to enhance diagnostic accuracy.[75][76] This approach counters purely relativistic views by prioritizing verifiable causal chains, as evidenced in studies reconstructing historical diagnostic strategies that infer disease from symptom patterns via etiological reasoning.[77] Ongoing debates highlight a resurgence of realist semiotics, drawing on Peircean triadic models to challenge Saussurean dyadic relativism amid concerns over "post-truth" erosion of referential stability. Proponents argue for hybrid frameworks that retain the signifier-signified dyad but incorporate a third element—such as a real-world referent or interpretant—to restore causal grounding and mitigate interpretive indeterminacy.[78] This shift, evident in 2023 metaphysical inquiries, critiques dyadic arbitrariness for fostering unchecked subjectivity, advocating instead for semiotic systems aligned with empirical inquiry and truth-tracking.[51] Such integrations aim to blend structuralist precision with pragmatic realism, particularly in countering relativist excesses in cultural analysis.[79]References

- https://www.[jstor](/page/JSTOR).org/stable/40246264