Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

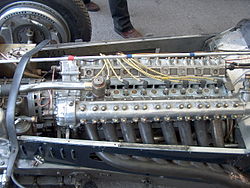

Straight-eight engine

View on Wikipedia

The straight-eight engine (also known as a inline-eight engine; abbreviated as I8) is an eight-cylinder internal combustion engine with all eight cylinders mounted in a straight line along the crankcase. The type has been produced in side-valve, IOE, overhead-valve, sleeve-valve, and overhead-cam configurations.

A straight-eight can be timed for inherent primary and secondary balance, with no unbalanced primary or secondary forces or moments. However, crankshaft torsional vibration, present to some degree in all engines, is sufficient to require the use of a harmonic damper at the accessory end of the crankshaft. Without such damping, fatigue cracking near the rear main bearing journal may occur, leading to engine failure.

Although an inline six-cylinder engine can also be timed for inherent primary and secondary balance, a straight-eight develops more power strokes per revolution and, as a result, will run more smoothly under load than an inline six. Also, due to the even number of power strokes per revolution, a straight-eight does not produce unpleasant odd-order harmonic vibration in the vehicle's driveline at low engine speeds.

The smooth running characteristics of the straight-eight made it popular in luxury and racing cars of the past. However, the engine's length demanded the use of a long engine compartment, making the basic design unacceptable in modern vehicles.[1] Also, due to the length of the engine, torsional vibration in both crankshaft and camshaft can adversely affect reliability and performance at high speeds. In particular, a phenomenon referred to as "crankshaft whip," caused by the effects of centrifugal force on the crank throws at high engine rpm, can cause physical contact between the connecting rods and crankcase walls, leading to the engine's destruction. As a result, the design has been displaced almost completely by the shorter V8 engine configuration.

Early period (1903–1918)

[edit]The first straight-eight was conceived by Charron, Girardot et Voigt (CGV) in 1903, but never built.[2][page needed] Great strides were made during World War I, as Mercedes made straight-eight aircraft engines like the Mercedes D.IV. Advantages of the straight-eight engine for aircraft applications included the aerodynamic efficiency of the long, narrow configuration, and the inherent balance of the engine making counterweights on the crankshaft unnecessary. The disadvantages of crank and camshaft twisting were not considered at this time, since aircraft engines of the time ran at low speeds to keep propeller tip speed below the speed of sound.

Unlike the V8 engine configuration, examples of which were used in De Dion-Bouton, Scripps-Booth, and Cadillac automobiles by 1914, no straight-eight engines were used in production cars before 1920.

Inter-war period (1919–1941)

[edit]Luxury automobiles

[edit]

Italy's Isotta Fraschini introduced the first production automobile straight-eight in their Tipo 8 at the Paris Salon in 1919[3] Leyland Motors introduced their OHC straight-eight powered Leyland Eight luxury car at the International Motor Exhibition at Olympia, London in 1920.[4][5] The Duesenberg brothers introduced their first production straight-eight in 1921.[6]: p48

Straight-eight engines were used in expensive luxury and performance vehicles until after World War II. Bugattis and Duesenbergs commonly used double overhead cam straight-eight engines. Other notable straight-eight-powered automobiles were built by Daimler, Mercedes-Benz, Isotta Fraschini, Alfa Romeo, Stutz, Stearns-Knight and Packard. One marketing feature of these engines was their impressive length — some of the Duesenberg engines were over 4 ft (1.2 m) long, resulting in the long hoods (bonnets) found on these automobiles.

Premium automobiles in the United States

[edit]In the United States in the 1920s, automobile manufacturers, including Hupmobile (1925), Chandler (1926), Marmon (1927), Gardner (1925), Kissel (1925), Locomobile (1925) and Auburn (1925) began using straight-eight engines in cars targeted at the middle class. Engine manufacturer Lycoming built straight-eight engines for sale to automobile manufacturers, including Gardner, Auburn, Kissel, and Locomobile. Hupmobile built their own engine. Lycoming was purchased by Auburn owner Errett Lobban Cord, who used a Lycoming straight-eight in his front-drive Cord L-29 automobile,[7] and had Lycoming build the straight-eight engine for the Duesenberg Model J, which had been designed by the Duesenberg brothers for the Cord-owned Duesenberg Inc.[8] The automobile manufacturers within the Cord Corporation, comprising Auburn, Cord, and Duesenberg, were shut down in 1937. Lycoming continues to this day as an aircraft engine manufacturer.

In the late 1920s, volume sellers Hudson and Studebaker introduced straight-eight engines for the premium vehicles in their respective lines. They were followed in the early 1930s by Nash (with a dual-ignition unit), REO, and the Buick, Oldsmobile, and Pontiac divisions of General Motors.

The Buick straight-eight was an overhead valve design, while the Oldsmobile straight-8 and Pontiac straight-8 straight-eights were flathead engines. Chevrolet, as an entry-level marque, did not have a straight-eight. Cadillac, the luxury brand of General Motors, stayed with their traditional V8 engines. In order to have engines as smooth as the straight-eights of its competitors, Cadillac introduced the crossplane crankshaft for its V8, and added V12 and V16 engines to the top of its lineup.

Ford never adopted the straight-eight; their entry-level Ford cars used flathead V8 engines until the 1950s while their Lincoln luxury cars used V8 from the 1930s to the 1980s and V12 engines in the 1930s and 1940s. Chrysler used flathead straight-eights in its premium Chrysler cars, including the Imperial luxury model.

Airships

[edit]The British R101 rigid airship was fitted with five Beardmore Tornado Mk I inline eight-cylinder diesel engines. These engines were intended to give an output of 700 bhp (520 kW) at 1,000 rpm but in practice had a continuous output rating of only 585 bhp (436 kW) at 900 rpm.[9]

Post-war

[edit]After World War II, changes in the automobile market resulted in the decline and eventual extinction of the straight-eight as an automobile engine. The primary users of the straight-eight were American luxury and premium cars that were carried over from before the war. A Flxible inter-city bus used the Buick straight-eight.

During World War II, improvements in the refinery technology used to produce aviation gasoline resulted in the availability of large amounts of inexpensive high octane gasoline. Engines could be designed with higher compression ratios to take advantage of high-octane gasoline. This led to more highly stressed engines which amplified the limitations of the long crankshaft and camshaft in the straight-eight engines.

Oldsmobile replaced their straight-eight flathead engine with its famous overhead valve Rocket V8 in 1949. Chrysler replaced its straight-eight with its famous Hemi V-8 for 1951. Hudson retired its straight-eight at the end of the 1952 model year. Buick introduced a 322 cu in (5.3 L) V8 in 1953, with similar displacement as their 320.2 cu in (5.2 L) straight-8, which was produced until the end of the 1953 model year. Pontiac maintained production on their straight-eight, as well as a L-head inline six, through the end of the 1954 model year, after which a V8 became standard. Packard ended production of their signature straight-eight at the end of 1954, replacing it with an overhead valve V8.[10][11]

By the end of the 1970s overhead valve V8s powered 80% of automobiles built in the US, and most of the rest had six-cylinder engines.[6]: pp99-103, 116–117

In Europe, many automobile factories had been destroyed during World War II, and it took many years before war-devastated economies recovered enough to make large cars popular again. The change in the design of cars from a long engine compartment between separate fenders to the modern configuration with its shorter engine compartment quickly led to the demise of the straight-8 engine. As a result of this, and of gasoline prices several times as expensive as in the U.S., four- and six-cylinder engines powered the majority of cars in Europe, and the few eight-cylinder cars produced were in the V8 configuration.[6]: pp99-113, 119–135

Military use

[edit]The British Army selected Rolls-Royce B80 series of straight-eight engines in the Alvis FV 600 armoured vehicle family. The Alvis Saladin armoured car was a 6x6 design with the engine compartment in the rear, a 76.2mm low pressure gun turret in the centre and the driver in front. The Saracen armoured personnel carrier had the engine in front with the driver in the centre and space for up to nine troops in the rear. The Stalwart amphibious logistics carrier has the driver's compartment over the front wheels, the larger B81 engine in the rear and a large load compartment over the middle and rear. The Salamander firefighting vehicle was unarmoured, and resembled the Stalwart with a conventional fire engine superstructure.

The Rolls-Royce B80 series of engines were also used in other military and civilian applications, such as the Leyland Martian military truck, the winch engine in the Centurion ARV, and various Dennis fire engines.

Performance and racing cars

[edit]

Despite the shortcomings of length, weight, bearing friction, and torsional vibrations that led to the straight-eight's post-war demise, the straight-eight was the performance engine design of choice from the late 1920s to the late 1940s, and continued to excel in motorsport until the mid-1950s. Bugatti, Duesenberg, Alfa Romeo, Mercedes-Benz, and Miller built successful racing cars with high-performance dual overhead camshaft straight-eight engines in the 1920s and 1930s.

The Duesenberg brothers introduced the first successful straight-eight racing engine in 1920, when their 3 L engine placed third, fourth, and sixth at the Indianapolis 500. The following year one of their cars won the French Grand Prix, while two others placed fourth and sixth in the race. Based on work the company had done on 16-cylinder aircraft engines during World War I, the overhead camshaft, three-valve-per-cylinder engine produced 115 brake horsepower (86 kW) at 4,250 rpm, and was capable of revving to an astonishing (at the time) 5,000 rpm. No Grand Prix engine before the war had peaked at more than 3,000 rpm.[12]: pp22–25

Bugatti experimented with straight-eight engines from 1922, and in 1924, he introduced the 2 L Bugatti Type 35, one of the most successful racing cars of all time, which eventually won over 1000 races. Like the Duesenbergs, Bugatti got his ideas from building aircraft engines during World War I, and like them, his engine was a high-revving overhead camshaft unit with three valves per cylinder. It produced 100 bhp (75 kW) at 5,000 rpm and could be revved to over 6,000 rpm. Nearly 400 of the Type 35 and its derivatives were produced, an all-time record for Grand Prix motor racing.[12]: pp26–29

Alfa Romeo were the first to react to the engineering problems of the straight-eight: in their racing car engines for the P2 and P3 and in their Alfa Romeo 8C 2300/2600/2900 sports cars of Mille Miglia and Le Mans fame the camshaft drive had been moved to the engine centre, between cylinders four and five, thus reducing the aforementioned limitations. The straight-eight was actually built as a symmetrical pair of straight-four engines joined in the middle at common gear trains for the camshafts and superchargers. It had two overhead camshafts, but only two valves per cylinder.[12]: pp34–37

The Alfa Romeo straight-eight would return after World War II to dominate the first season of Formula One racing in 1950, and to win the second season against competition from Ferrari's V12-powered car in 1951. The Alfa Romeo 158/159 Alfetta was originally designed in 1937 and won 47 of 54 Grands Prix entered between 1938 and 1951 (with a six-year gap in the middle caused by the war). By 1951, their 1.5 L supercharged engines could produce 425 bhp (317 kW) at 9,300 rpm, and could rev as high as 10,500 rpm. However, the engines were at the end of their potential, and rule changes for the 1952 season made the Alfettas obsolete.[12]: pp67–69

Mercedes-Benz would create the last notable straight-eight racing cars in 1955, with the championship-winning W196 Formula One racing car and the 300SLR sports racing car. The 300SLR was famous for Stirling Moss and Denis Jenkinson's victory in the 1955 Mille Miglia, but notorious for Pierre Levegh's deadly accident at the 1955 24 Hours of Le Mans. The 300SLR was the final development of the Alfa Romeo design of the early 1930s as not only the camshaft, but now also the gearbox was driven from the engine's centre. Engineers calculated that torsional stresses would be too high if they took power from the end of the long crankshaft, so they put a central gear train in the middle (which also ran the dual camshafts, dual magnetos, and other accessories) and ran a drive shaft to the clutch housing at the rear.[12]: pp94-97

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Moore, Stephen J. (2020). A Detailed History of the Straight-Eight Automobile Engine. Self-published on USB. ISBN 978-0-473-54810-0.

- ^ Georgano, G. N. (1985). Cars: Early and Vintage, 1886–1930. London: Grange-Universal.

- ^ Posthumus, Cyril (1977) [1977]. "War and Peace". The story of Veteran & Vintage Cars. John Wood, illustrator (Phoebus 1977 ed.). London: Hamlyn / Phoebus. p. 70. ISBN 0-600-39155-8.

- ^ Welsh Motor Sport - Cars

- ^ Histomobile: Leyland - 1920s

- ^ a b c Daniels, Jeff (2002). Driving Force: The Evolution of the Car Engine. Haynes Publishing. ISBN 1-85960-877-9.

- ^ Wise, David Burgess. "Cord: The Apex of a Triangle", in Northey, Tom, ed. World of Automobiles (London: Orbis, 1974), Vol. 4, pp.435-436.

- ^ Cheetham, Craig (2004). Vintage Cars. Motorbooks. p. 73. ISBN 9780760325728. Retrieved 2010-11-23.

- ^ "Boulton and Paul - the R101." norfolkancestors.org. Retrieved: 27 August 2010.

- ^ Hemmings Classic Car Volume 6 issue 5, February 2010 page 39

- ^ Murilee Martin (2008-04-17). "Jalopnik Engine of the Day, Apr 17, 2008: Packard Inline Eight". Jalopnik.com. Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- ^ a b c d e Ludvigsen, Karl (2001). Classic Racing Engines. Haynes Publishing. ISBN 1-85960-649-0.

Websites

[edit]- Davies, John William. "Welsh Motor Sport - Cars". John William Davies. Archived from the original on 2012-10-09. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- van Damme, Stéphane. "Histomobile: Leyland - 1920s". Stéphane van Damme. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

Straight-eight engine

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and configuration

The straight-eight engine, also known as the inline-eight, is an internal combustion engine configuration consisting of eight cylinders arranged in a single straight line along a shared crankshaft.[6] This layout allows all pistons to reciprocate parallel to one another, driving the crankshaft in a linear fashion typical of inline designs.[7] The configuration emerged in the early 20th century as an evolution from smaller inline engines, such as four- and six-cylinder variants, providing increased displacement and power for demanding applications while maintaining inherent smoothness.[8] Central to its design are a single cylinder head that covers all eight cylinders, a unified valvetrain for efficient operation across the bank, and a robust crankshaft tailored to the extended length, often supported by seven main bearings in typical automotive implementations to minimize flex and ensure durability.[1] Firing orders varied by manufacturer, but a common one for many straight-eight engines, such as those in American luxury cars, is 1-6-2-5-8-3-7-4, which delivers even 90-degree intervals between combustion events, promoting balanced power delivery and reduced vibration for refined performance.[9] Displacement in these engines ranged from compact early units around 3 liters to expansive luxury variants reaching up to 7.2 liters in prototypes, accommodating diverse power needs.[6] Compared to V8 configurations, the straight-eight's elongated form factor demands more longitudinal space in vehicle chassis.[7]Balance and performance characteristics

The straight-eight engine exhibits inherent primary and secondary balance owing to its evenly spaced cylinders and appropriate firing order, such as 1-6-2-5-8-3-7-4, which cancels out unbalanced forces and moments without requiring balance shafts.[10] This configuration results in exceptionally low vibration levels, contributing to the engine's reputation for refinement in operation.[1] The firing order also delivers smooth power pulses, with eight evenly spaced combustion events every two crankshaft revolutions, providing superior driveline smoothness and reduced torque fluctuations compared to inline-six or V8 engines of similar displacement.[11] This even delivery enhances overall engine refinement, making straight-eights particularly suitable for luxury applications where passenger comfort is paramount.[12] In terms of performance, straight-eight engines typically feature a broad torque curve with strong low-end output, ideal for steady cruising in heavy luxury vehicles; for instance, Buick's straight-eight variants were noted for their abundant low-rpm torque.[4] Peak horsepower in 1930s luxury car examples often reached 200-300 hp, as seen in the Duesenberg Model J's 420-cubic-inch straight-eight producing 265 hp at 4,200 rpm.[13] However, the long engine block presents cooling and lubrication challenges, as coolant and oil must travel greater distances to reach distant cylinders and bearings, potentially leading to uneven temperatures and pressure drops at high speeds.[14] Manufacturers addressed lubrication issues with multi-point oil delivery systems, including pressure-fed lines to main and rod bearings to ensure adequate supply across the extended crankcase.[15] To counter crankshaft flex, or "whip," resulting from the long rotating assembly, engineers employed counterweighted crankshafts and additional main bearings—often seven or nine—to stiffen the design and minimize torsional vibrations at higher rpm.[16]Historical development

Early development (1903–1918)

The straight-eight engine configuration emerged in the early 1900s as engineers sought greater power and smoother operation beyond four- and six-cylinder designs. The first known straight-eight was conceived by the French firm Charron, Girardot et Voigt (CGV) in 1903, a 7.2-litre inline-eight racing engine design without a conventional gearbox, designed for high-speed competition and marking an experimental leap in multi-cylinder automotive engineering.[17] This prototype, heavily influenced by Panhard designs, represented one of the earliest attempts to harness eight cylinders in a straight layout for enhanced torque and reduced vibration compared to contemporaries.[18] Early automotive applications remained limited to experimental trials in Europe, where manufacturers grappled with the configuration's complexity in road-going vehicles. Isotta Fraschini conducted pioneering work on straight-eight designs during this period, initially adapting multi-cylinder concepts for racing and later aircraft use, though full production automotive integration occurred post-war.[19] These efforts highlighted the engine's potential for high performance but underscored its challenges in packaging within compact chassis, often restricting it to specialized racers rather than mass-market cars. The smoothness of the straight-eight, arising from its even firing order, offered conceptual advantages over inline-sixes for luxury and speed applications, though practical adoption lagged until wartime innovations.[8] World War I accelerated straight-eight development, particularly in aviation, where the layout's narrow profile enabled slimmer fuselages for improved aerodynamics in reconnaissance aircraft. German engineers at Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft produced the Mercedes D.IV, a 220-horsepower liquid-cooled inline-eight that powered prototypes like the AEG C.V biplane reconnaissance plane, allowing for better forward visibility and stability during long-range missions.[20][21] This engine's geared propeller drive represented an advance in power delivery, though production was limited due to reliability issues in combat conditions. Similarly, the Kondor W.2C reconnaissance floatplane employed the Mercedes D.IV for its compact installation, emphasizing the configuration's role in fitting powerful engines into constrained airframe designs.[22] Overcoming technical hurdles was essential for the straight-eight's viability, especially in ensuring reliable operation across eight cylinders. Early carburetion systems struggled with even fuel distribution to distant cylinders, often leading to uneven power and incomplete combustion, while magneto-based ignition setups faced synchronization difficulties under varying loads, risking misfires in multi-cylinder arrays.[8] Innovations in manifold design and dual ignition circuits during wartime addressed these, improving reliability for aircraft applications and paving the way for postwar automotive use. Additionally, the long crankshaft prone to torsional vibration—known as "crankshaft whip"—posed structural challenges, requiring reinforced bearings and damping to maintain integrity at high revs.[8]Interwar expansion (1919–1941)

Following the end of World War I, the straight-eight engine experienced significant adoption in luxury automobiles, driven by demands for smoother operation and higher power in premium vehicles. The Bugatti Type 30, introduced in 1922, marked an early icon in this surge, featuring a 2.0-liter supercharged straight-eight engine that delivered around 90 horsepower and enabled top speeds of up to 145 km/h (90 mph), establishing Bugatti's reputation for performance engineering in the interwar era.[23] This configuration's inherent balance contributed to its appeal in high-end touring and racing applications, reflecting the postwar shift toward more sophisticated inline multi-cylinder designs. In the United States, straight-eight engines entered the premium market prominently in the mid-1920s, evolving from earlier V12 architectures to offer comparable refinement with simpler construction. Packard's 1924 Single Eight represented a key transition, replacing the prewar Twin Six V12 with a 5.9-liter straight-eight producing 85 horsepower, which powered the company's top-line models and solidified its position in luxury motoring through enhanced smoothness and reliability.[24] By 1931, Buick advanced the technology further with its overhead-valve straight-eight engines, with displacements ranging from 3.6 L (77 horsepower) to 5.7 L (104 horsepower) in various models, notable for their five main bearings and innovative valvetrain that improved efficiency and durability in mass-produced luxury sedans.[25] European manufacturers emphasized straight-eights for competitive performance and racing heritage during this period. Alfa Romeo's 8C, launched in 1931, utilized a twin-supercharged 2.3-liter straight-eight engine outputting up to 180 horsepower, powering lightweight chassis to victories at Le Mans and the Mille Miglia, and embodying Italian engineering prowess in grand prix and sports car racing.[26] Similarly, Maserati's 8C of 1933 featured a 3.0-liter supercharged straight-eight delivering approximately 260 horsepower, which competed effectively in European grands prix and contributed to the marque's legacy in high-speed circuit events.[27] The economic prosperity of the 1920s facilitated the development of high-displacement straight-eights in luxury cars, allowing for greater power outputs to match the era's opulent designs. The Duesenberg Model J, introduced in 1928, exemplified this with its 6.9-liter dual-overhead-cam straight-eight producing 265 horsepower, capable of accelerating to 100 mph and becoming a symbol of American extravagance during the boom years.[28]Postwar applications (1945–1960)

Following World War II, the straight-eight engine persisted primarily in American premium automobiles, where its inherent smoothness appealed to luxury buyers despite emerging competition from V8 designs. Pontiac continued production of its straight-eight from 1933 through 1954, evolving the engine to a displacement of 268 cubic inches (4.4 L) by 1950, delivering 108 horsepower by 1950 and up to 127 horsepower in 1954 for models like the Chieftain.[29] Buick similarly retained the configuration in its lineup until 1953, when the 263-cubic-inch (4.3 L) version powered the entry-level Special series as the final straight-eight offering before the shift to overhead-valve V8s in higher trims.[4][25] In Europe, the straight-eight experienced a rapid wind-down in automotive applications, as manufacturers prioritized more compact and efficient alternatives amid postwar reconstruction and fuel constraints. Luxury brands like Lagonda had used straight-eight engines pre-war but postwar focused on straight-six designs from 1948, with limited V12 production ending before the war.[30] Similarly, early Jaguar models post-1945 focused on the XK inline-six, sidelining any lingering straight-eight concepts from prewar SS Cars heritage.[31] Military adaptations extended the straight-eight's relevance into the late 1940s and 1950s, particularly in British armored vehicles where balance and reliability suited tracked and wheeled designs. The Rolls-Royce B80, a 5.7-liter straight-eight petrol engine producing 170 horsepower, powered the Alvis Saladin FV601 armored car, which entered service in 1958 and saw widespread use in reconnaissance roles across Commonwealth forces.[32][33] This engine, part of the Rolls-Royce B-series, also equipped related vehicles like the Saracen APC, providing a smooth power delivery for off-road operations until diesel alternatives emerged in the 1960s.[34] Experimental marine applications highlighted the straight-eight's versatility in diesel form during the late 1940s. The U.S. Navy trialed opposed-piston straight-eight diesels, such as the Fairbanks-Morse 38D8-1/8, a 1,000-horsepower inline-eight with a 38-inch stroke, in prototypes for small warships and submarines to enhance surface propulsion and reliability over earlier radial designs.[35][36] These engines proved durable in high-vibration environments, powering Balao- and Guppy-class submarines through the 1950s before nuclear propulsion reduced their role.[37] By the mid-1950s, signals of decline became evident as overhead-valve V8 engines offered superior power density and easier integration into compact chassis, exacerbating the straight-eight's packaging challenges in smaller postwar vehicles. The long crankshaft and block length demanded extended engine bays, limiting maneuverability in designs prioritizing shorter hoods for better weight distribution and aerodynamics.[7][5] This shift culminated in the configuration's automotive obsolescence by 1955, though its legacy endured in specialized military and marine roles.[8]Applications

Automotive uses

The straight-eight engine found prominent application in luxury automobiles during the interwar period, prized for its inherent balance that contributed to exceptionally smooth operation and refinement suitable for high-end road cars.[13] In the luxury segment, the Duesenberg Model SJ exemplified the pinnacle of American engineering in the 1930s, featuring a supercharged 6.9-liter straight-eight that delivered up to 400 horsepower, enabling top speeds exceeding 140 mph in a chassis designed for bespoke coachwork.[38] As an alternative to multi-cylinder configurations like Cadillac's V-16, straight-eights powered select premium chassis such as Buick's Series 80 models in the 1930s, where their overhead valve design provided reliable torque for opulent sedans and limousines.[25] Premium U.S. models further showcased the straight-eight's versatility in upscale road vehicles. Chrysler's Imperial line from the 1930s employed a robust flathead straight-eight, such as the 384-cubic-inch (6.3-liter) unit in the 1931 model producing 125 horsepower, which offered a blend of power and prestige for touring cars with LeBaron styling.[39] Oldsmobile continued using straight-eights through the 1940s, including the 257-cubic-inch (4.2-liter) version in pre-1950 Series 70 and 90 cars that generated around 100 horsepower, serving as a smooth powerplant before the marque's shift to overhead-valve V-8s.[40] European manufacturers emphasized elegance with straight-eight power for coachbuilt bodies. The Isotta Fraschini Tipo 8A, introduced in 1929, utilized a 7.4-liter overhead-valve straight-eight rated at 130 horsepower, attracting celebrities and royalty with its four-speed gearbox and customizable frames from houses like Castagna.[41] In large luxury sedans of the era, straight-eight engines typically achieved fuel economy of 10-15 miles per gallon, reflecting the trade-offs of their size and side-valve designs, though evolutions to overhead-valve configurations in the late 1930s improved efficiency and maintenance accessibility.[42] Key iconic vehicles powered by straight-eight engines include:- Duesenberg Model SJ (1932-1937): 6.9-liter supercharged, 400 horsepower, renowned for luxury speedsters.[38]

- Packard One-Twenty (1935-1940): 4.0-liter flathead, 100 horsepower, a more accessible premium sedan.[43]

- Chrysler Imperial Eight (1931): 6.3-liter, 125 horsepower, flagship for cross-country touring.[39]

- Oldsmobile Series 90 (1937-1940): 4.2-liter, 115 horsepower, emphasizing everyday refinement.[40]

- Buick Series 80 (1931-1935): 3.8-liter overhead-valve, 100 horsepower, a staple in upscale family cars.[25]

- Isotta Fraschini Tipo 8A (1929-1931): 7.4-liter, 130 horsepower, symbol of continental sophistication.[41]

- Hudson Eight (1936): 4.2-liter, 120 horsepower, blending performance with streamlined styling.[44]