Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

French Grand Prix

View on Wikipedia

| Circuit Paul Ricard | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 90 |

| First held | 1906 |

| Last held | 2022 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Circuit length | 5.842 km (3.630 miles) |

| Race length | 309.690 km (192.432 miles) |

| Laps | 53 |

| Last race (2022) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

The French Grand Prix (French: Grand Prix de France), formerly known as the Grand Prix de l'ACF (Automobile Club de France), is an auto race held as part of the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile's annual Formula One World Championship. It is one of the oldest motor races in the world as well as the first "Grand Prix". It ceased, shortly after its centenary, in 2008 with 86 races having been held, due to unfavourable financial circumstances and venues. The race returned to the Formula One calendar in 2018 with Circuit Paul Ricard hosting the race, but was removed from the calendar after 2022.

Unusually even for a race of such longevity, the location of the Grand Prix has moved frequently with 16 different venues having been used over its life, a number only eclipsed by the 23 venues used for the Australian Grand Prix since its 1928 start. It is also one of four races (along with the Belgian, Italian and Spanish Grands Prix) to have been held as part of the three distinct Grand Prix championships (the World Manufacturers' Championship in the late 1920s, the European Championship in the 1930s and the Formula One World Championship since 1950).

The Grand Prix de l'ACF was tremendously influential in the early years of Grand Prix racing, leading the establishment of the rules and regulations of racing as well as setting trends in the evolution of racing. The power of the original organiser, the Automobile Club de France, established France as the home of motor racing organisation.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]France was one of the first countries to hold motor racing events of any kind. The first competitive motor race, the Paris to Rouen Horseless Carriages Contest was held on 22 July 1894, and was organized by the Automobile Club de France (ACF). The race was 126 km (78 mi) long and was won by Count Jules-Albert de Dion in his De Dion Bouton steam powered car in just under 7 hours. This race was followed by races starting in Paris to various towns and cities around France such as Bordeaux, Marseille, Lyon and Dieppe, and also to various other European cities such as Amsterdam, Berlin, Innsbruck and Vienna. The 1901 Paris-Berlin race was noteworthy as the race winner, Henri Fournier averaged an astonishing 57 mph (93 km/h) in his Mors, but there were details of other incidents. A competitor driving a 40H.P. Panhard suddenly found the road blocked by a tram in the village of Metternich, and he deliberately ran into the vehicle to avoid the crowd of spectators. The tram was knocked off the rails; the car was hardly damaged. And in Reims, a future location of many French Grands Prix, another competitor in a Mors hit and killed a child who wandered onto the road.

But these races, held on public dirt roads that were not all closed to the public came to a halt in 1903. The Paris-Madrid race, a 1,307 km (812 mi) long competition from the French capital to the Spanish capital held in May of that year had over 300 entrants. Some of the cars were doing 140 km/h (87 mph)- an astonishingly fast speed for the time- not even rail locomotives were capable of hitting these speeds. It was not known at the time how safe these races would be or how these cars- made mostly of wood would perform, and development of the car had improved significantly over 9 years. The race was a disaster, with 8 people killed and over 15 injured in multiple accidents- and all of this happened before any of the competitors reached the Spanish border. Crowds of onlookers would stand right on the edge of the track, and children were wandering into the roads which became very dusty, and visibility was limited at best. The most notable fatality of this race was one Marcel Renault, one of the 3 brothers who founded the Renault car company, a manufacturer that would go on to have lots of success in Grand Prix racing many decades later and be a huge influence on French motorsport. When Renault reached the village of Payré just south of Grand Poitiers he lost control of his 16HP Renault in poor visibility caused by excess dust. The car went into a gutter and crashed into a tree, and Renault sustained a horrific wound in the side of his head and dislocated his shoulder. Fellow competitor Leon Théry stopped his Decauville in order to help Renault and his riding-mechanic Vauthier, still trapped in their car. No doctors were on hand, but Théry found one at the next village and sent him to the place of accident- the doctor rode a bicycle to get to the accident. The doctor conveyed Renault back to the nearest hospital in Grand Poitiers, where Renault succumbed to his injuries two days later, while Vauthier survived with minor injuries. Accidents continued throughout the day; cars hit trees and disintegrated, they overturned and caught fire, axles broke and inexperienced drivers crashed on the rough roads. The race was eventually called off by the French government and there was no declared winner. The cars were impounded by the French authorities, towed to the nearest rail stations by horses and transported back to Paris by train. The race created a political uproar in France, and a French magazine did their own investigation into the race. Speed, dust created by the cars, poor organization and lack of crowd control were to blame for these tragedies and even French Prime Minister Émile Combes was held partially responsible because he was the ultimate authority on allowing the race to proceed.

Other races were organized by American newspaper publisher James Gordon Bennett called the Gordon Bennett Cup, 4 of which were in France. 3 city-to-city races in 1900, 1901 and 1902, all starting in Paris were organized by Bennett and they attracted top racers from the United States and Western Europe. But after the 1903 Paris-Madrid race, the French government banned point-to-point car races on open public roads, so Bennett moved the 1903 race to Ireland on a closed circuit 2 months after Paris-Madrid, the first of its kind. This race was won by Belgian Camille Jenatzy in a Mercedes, who was one of the bravest and most fearless racing drivers of his time. The 1904 race was held in western Germany while the last Gordon Bennett Cup race was held in an 137 km (85 mi) circuit in Auvergne in south-central France. The race started in Clermont-Ferrand, and was run over 4 laps, and was won by Théry in a Brasier.

The world's oldest Grand Prix

[edit]Closed public road courses

[edit]

The French Grand Prix, open to international competition was first run on 26 June 1906 under the auspices of the Automobile Club de France in Sarthe with a starting field of 32 automobiles. The Grand Prix name ("Great Prize") referred to the prize of 45,000 French francs to the race winner.[1] The franc was pegged to gold at 0.290 grams per franc, which meant that the prize was worth 13 kg of gold, or US$210,700 adjusted for inflation. The earliest French Grands Prix were held on circuits consisting of public roads near towns through northern and central France, and they usually were held at different towns each year, such as Le Mans, Dieppe, Amiens, Lyon, Strasbourg, and Tours. Dieppe in particular was an extremely dangerous circuit – 9 people (5 drivers, 2 riding mechanics, and 2 spectators) in total were killed at the three French Grands Prix held at the 79 km (49-mile) circuit.

The 1906 race was the first ever national race named "Grand Prix" (the "Grand Prix" mention appeared in France in 1900 as a sub-category name for entries for the Circuit du Sud-Ouest in Pau, where the word "Grand Prix" was initially used for horse racing competitions, the name Grand Prix was then used to describe the whole race in 1901); other, later, international events in the 1900s and 1910s in Europe and the United States had their own names with the term "Prize" in them, such as Grand Prize in America or Kaiserpreis (English: Emperor's Prize) in Germany. The French Grand Prix race was run on a very fast 66-mile (106 km) one-off anti-clockwise closed public road circuit east of the small western French city of Le Mans, starting in the village of Saint-Mars-la-Briere. It then went down the Route D323 and turned a hard left onto Route D357 near the commune of Yvre-l-Eveque onto a 4-mile straight towards the village of La Butte, then down a 15-mile straight through Bouloire and then into a twisty section in Saint-Calais. The circuit then went north on Route D1 through Berfay and then entered a purpose-built twisty section made of wooden logging track in a forest before Vibraye and then went north again, entering a series of fast corners in and near Lamnay, and then turned west at La Ferte-Bernard. The circuit then went down Route D323 again and down multiple straights 3 to 6 miles long with a few fast corners at Sceaux-sur-Huisne and Conerre, before returning to the pits at Saint-Mars-la-Briere. Circuits in Europe that went through multiple rural towns like this one became ever more common on public road circuits in France and other European countries. Long straights also became a staple of circuits in France, particularly at future iterations of the relocated Sarthe circuit at Le Mans- a city that would host another race that would become a fixed staple in motor racing circles. The Hungarian Ferenc Szisz won this very long 12‑hour race on a Renault from Italian Felice Nazzaro in a Fiat, where laps on this circuit took just under an hour and the horse carriage road surface was made of dirt; even so this did not stop the fastest lap average speed being 73.37 mph (118.09 km/h)- an astonishingly fast speed for the time. The 1908 race saw Mercedes humiliating the French organizers and finishing 1-2-3 at the lethal circuit at Dieppe, where no less than 4 people were killed during the weekend. The 1913 race was won by Georges Boillot on a one-off 19-mile (31 km) circuit near Amiens in northern France. Amiens was another deadly circuit – it had a 7.1 mile straight and 5 people were killed during its use during pre-race testing and the race weekend itself.

The 1914 race, run on a 23‑mile circuit near Lyon is perhaps the most legendary and dramatic Grand Prix of the pre‑WWI racing era. This circuit, which was popular with drivers and spectators had a twisty and demanding section down to the town of Le Madeline and then an 8.3 mile straight interrupted by a hairpin which returned to the pits. This race was a hard-fought battle between the French Peugeots and the German Mercedes. Although the Peugeots were fast and Boillot ended up leading for 12 of the 20 laps after Max Sailer in a Mercedes unexpectedly dropped out with engine failure on Lap 6, the Dunlop tyres they used wore out badly compared to the Continentials that the Mercedes cars were using. Boillot's four-minute lead was wiped out by Christian Lautenschlager in a Mercedes while Boillot stopped an incredible eight times for tyres. Although Boillot drove very hard to try to catch Lautenschlager, he had to retire on the last lap due to engine failure, and for the second time in 6 years Mercedes finished 1–2–3; a humiliating result for the organizers and Peugeot.

Because of World War I and the amount of damage it did to France, the Grand Prix was not brought back until 1921, and that race was won by American Jimmy Murphy with a Duesenberg at the Sarthe circuit at Le Mans, which was the now legendary circuit's first year of operation. Bugatti made its debut at the 1922 race at an 8.3‑mile (13 km) one-off public road circuit near Strasbourg near the French-German border – which was very close to Bugatti's headquarters in Molsheim. It rained, and the muddy semi-rectangular circuit, made up of long straights, 90 degree corners, a fast kink and a hairpin was in a dreadful condition. This race became a duel between Bugatti and Fiat – and Felice Nazzaro won in a Fiat, although his nephew and fellow competitor Biagio Nazzaro was killed after the axle on his Fiat broke, threw a wheel and hit a tree; the 32-year old and his riding mechanic both suffered fatal head injuries. The 1923 race at another one-off circuit near Tours featured another new Bugatti – the Type 32. This car was insultingly dubbed the "Tank", owing to its streamlined shape and very short wheelbase. This car was quick on the long straights of this very fast 14 mile (23 km) public road circuit – but it handled badly and was outpaced by Briton Henry Segrave in a supercharged Sunbeam, supercharging being a common feature of Grand Prix cars during this period. Segrave won the race, and the Sunbeam would be the last British car to win an official Grand Prix until Stirling Moss's victory with a Vanwall at the 1957 British Grand Prix. Segrave, a known teetotaler was given a glass of champagne after his victory, because apparently there wasn't any water available in the pits area. The 1924 race was held again at Lyon, but this time on a shortened 14‑mile variant of the circuit used in 1914. Two of the most successful Grand Prix cars of all time, the Bugatti Type 35 and the Alfa Romeo P2 both made their debuts at this race. The Bugattis, with their advanced alloy wheels suffered tyre failure, and Italian Giuseppe Campari won in his Alfa P2.

France's first permanent circuit and other public road circuits

[edit]

In 1925, the first permanent autodrome in France was built, it was called Autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry, located 20 miles south of the centre of Paris. The 7.7‑mile (12.3 km) circuit included a 51‑degree concrete banking, an asphalt road course and then-modern facilities, including pit garages and grandstands. Purpose-built autodromes like Montlhéry were often built near the country's largest cities (with the exception of Indianapolis and the Nürburgring). After the construction of Brooklands near London in England in 1907, and Indianapolis in the United States in 1908 and after World War I, Monza near Milan in Italy was opened in 1922, and Sitges–Terramar near Barcelona in Spain was also opened in 1923. The French were then prompted to construct a purpose-built racing circuit at Montlhéry in the north and then Miramas in the south. The Nürburgring in western Germany followed in 1927, to complement eastern Germany's AVUS street circuit. Montlhery first held the Grand Prix de l'ACF in 1925 as part of the inaugural World Manufacturers' Championship, the first time Grands Prix were grouped together to form a championship. The circuit drew huge crowds and they were witnesses to the spectacular sight of fast cars racing on Montlhéry's steep banking and asphalt road course, which had many fast corners and long straights, and was located in a forest. The first race at Montlhéry was marred by the fatal accident of Antonio Ascari in an Alfa P2, when he crashed at a very fast left-hand kink returning to the oval portion. Miramas, a high-banked concrete oval track like Brooklands and part of Montlhéry was completed in 1926, and it played host to the Grand Prix that year. This race saw only three cars compete, all Bugattis, and was won by Frenchman Jules Goux, who had also won the Indianapolis 500 in 1913.

The 1927 race at Montlhéry was won by Frenchman Robert Benoist in a Delage. 1929 saw a brief return to Le Mans, which was won by William Grover-Williams in a Bugatti; this was the man who had won the first ever Monaco Grand Prix earlier in the year; Grover-Williams had also won the 1928 race in a Bugatti at the 17-mile (28 km) Saint-Gaudens circuit in the south, not far from Toulouse. The 1930 French Grand Prix, held at Pau back down in the south was one of the more memorable French Grands Prix of the pre-World War II period. This race, held in September on a one-off triangular 9.8‑mile (15.8 -km) public road circuit just a few kilometres away from the current Pau Grand Prix track saw a special supercharged version of the famous Bentley 4½ Litre called the Blower Bentley compete in the race with Briton and "Bentley Boy" Tim Birkin driving. The Bentley team had been dominating the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and this Blower Bentley had its headlights and mudguards removed, as these were not needed for this race, giving it the appearance of an open-wheel car. The Bentley, which was much larger and heavier than the small Bugattis around it performed well – at this very fast circuit which was made up of very long straights and tight hairpins actually suited the powerful Blower Bentley, and it enabled Birkin to pass the pits at 130 mph (208 km/h) (very fast for that time), and he overtook car after car – to the amazement of the crowd. But he finished second to Frenchman Philippe Étancelin in a Bugatti.

Montlhéry would also be part of the second Grand Prix championship era; the European Championship when it began in 1931. Other public road circuits also played host to French Grand Prix, such as the fast, straight and slow corner-dominated 4.8‑mile Reims-Gueux circuit in the Champagne wine region of Northern France 144 km (90 mi) east of Paris for 1932, where Italian legend Tazio Nuvolari won in an Alfa Romeo. But from 1933 to 1937 Montlhéry would become the sole host of the event. The 1934 French Grand Prix marked the return of Mercedes-Benz to Grand Prix racing after 20 years, with an all-new car, team, management, and drivers, headed by Alfred Neubauer. 1934 was the year where the German Silver Arrows debuted (an effort heavily funded by Hitler's Third Reich), with Auto Union having already debuted its powerful mid-engined Type–A car for a race at AVUS in Germany. Although the Monégasque driver Louis Chiron won in an Alfa, the Silver Arrows dominated the race. The high-tech German cars seemed to float over the rough concrete banking at Montlhéry where all the other cars seemed to be visibly affected by the concrete surface. Makeshift chicanes were placed at certain points on the high-speed circuit in an effort by the French to slow the very fast German cars down for the 1935 race, but this effort came to nothing as Mercedes superstar Rudolf Caracciola won that year's race. The French Grand Prix then became a sportscar race for 1936 and 1937.

Reims, Rouen and Charade

[edit]

The French Grand Prix returned to the Reims-Gueux circuit for 1938 and 1939, where the Silver Arrows continued their domination of Grand Prix racing. The Reims-Gueux circuit had its straights widened and facilities updated for the 1938 race. It was around this time that the French Grand Prix had some of its prestige transferred after 2 years of being a sportscar race- the Monaco Grand Prix had gained a huge amount of prestige and would become the premier French-related Grand Prix event, taking place in a tiny principality surrounded by France; but the French Grand Prix was still an important race now held traditionally on the first weekend of July. But when World War II began, the French Grand Prix did not come back until 1947, where it was held at the one-time Parilly circuit near Lyon, a race that was marred by an accident involving Pierre Levegh crashing into and killing 3 spectators. After that, Grand Prix racing returned to Reims-Gueux, where another manufacturer – Alfa Romeo – would dominate the event for 4 years. 1950 was the first year of the Formula One World Championship, but all the Formula One-regulated races were held in Europe. The race was won by Argentine Juan Manuel Fangio, who also won the next year's race – the longest Formula One race ever held in terms of distance covered, totalling 373 miles.

The prestigious French event was held for the first time at the Rouen-Les-Essarts public road circuit in 1952, where it would be held four more times over the next 16 years. Rouen was a very high speed circuit located in the northern part of the country, that was made up mostly of high speed bends. But the race returned to Reims in 1953, where the triangular circuit, which was originally made up of three long straights (with a few slight kinks) two tight 90 degree right hand corners and a very slow right hand hairpin had been modified to bypass the town of Gueux, making what was already regarded as a very fast circuit even faster. Reims now had two straights (including the even longer back straight), three very fast bends and two very slow and tight hairpins. This race was a classic, with Fangio in a Maserati and Briton Mike Hawthorn in a Ferrari having a race-long battle for the lead, with Hawthorn taking the checkered flag. 1954 was another special event, and this marked Mercedes's return to top-flight road racing led by Alfred Neubauer, 20 years after their first return to Grand Prix racing – in France. After two wins for the works Maserati team that year at Buenos Aires and Spa, Fangio was now driving for Mercedes and he and teammate Karl Kling effectively dominated the race from start to finish with their advanced W196's. It was not a popular win – Mercedes, a German car manufacturer, had won on French soil – only 9 years after the German occupation of France had ended. The French Grand Prix was cancelled in 1955 because of the Le Mans disaster, and Mercedes withdrew from all racing at the end of that year. The race continued to be held at Reims in 1956, another spell at a lengthened Rouen-Les-Essarts in 1957 and back to Reims again from 1958 to 1961, 1963 and one last event in 1966 at this circuit, located where champagne is made. The 1956 race saw a one-off appearance by Bugatti- they entered a new mid-engined Grand Prix car (which was a novelty at the time, and only the second Grand Prix car ever to be designed this way after the 1930s Auto Unions) designed by renowned Italian engineer Colombo and driven by Maurice Trintignant, but the car was underpowered, overweight, and over-complicated, and it proved to be very difficult to drive; it retired early in the race. The 1958 race was marred by the fatal accident of Italian Luigi Musso, driving a works Ferrari, and it was also Fangio's last Formula One race. Hawthorn, who like many other F1 drivers at the time, held Fangio in very high regard; and was about to lap Fangio (driving in an outdated Maserati) on the last lap on the pit straight when he slowed down and let Fangio cross the line before him so the respected Argentine driver could complete the whole race distance. Hawthorn won, and Fangio finished fourth. 1961 saw the race being held in 100 °F (38 °C) weather, and the track broke up at the hairpins. The race came down to a slipstreaming battle between American Dan Gurney in a Porsche and Italian Giancarlo Baghetti in the sharknose Ferrari. Baghetti won the race- which astonishingly was his first ever championship Grand Prix by less than a car's length from Gurney.

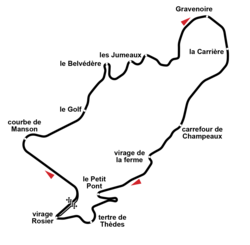

Rouen-Les-Essarts hosted the event in 1962 and 1964, and Gurney won both these events, one in a Porsche and another in a Brabham. In 1965 the race was held at the 5.1 mile Charade Circuit in the hills surrounding Michelin's hometown of Clermont-Ferrand in central France. Unlike the long straights that made up Reims and the fast curves that made up Rouen, Charade was known as a mini-Nürburgring and was twisty, undulating and very demanding. In 1966, 34 years after first hosting this prestigious event Reims staged its last French Grand Prix, with Australian Jack Brabham winning in a car bearing his name. The short Bugatti Circuit at Le Mans held the race in 1967, but the circuit was not liked by the Formula One circus, and it never returned. Rouen-Les-Essarts hosted the event in 1968, and it was a disastrous event; Frenchman Jo Schlesser crashed and was killed at the very fast Six Frères corner in his burning Honda, and Formula One did not return to the public-road circuit. Charade hosted two more events, and then Formula One moved to the newly built, modern Circuit Paul Ricard on the French riviera for 1971. Paul Ricard Circuit, located in Le Castellet, just outside Marseille and not far from Monaco, was a new type of modern facility, much like Montlhéry had been in the 1920s. It had run-off areas, a wide track and ample viewing areas for spectators. Charade hosted the event one last time in 1972; Formula One cars had become too fast for public road circuits; the circuit was littered with rocks and Austrian Helmut Marko was hit in the eye by a rock thrown up from Brazilian Emerson Fittipaldi's Lotus which ended his racing career.

Le Castellet and Dijon-Prenois

[edit]

Formula One returned to Paul Ricard in 1973; the French Grand Prix was never run on public road circuits like Reims, Rouen and Charade ever again. Paul Ricard circuit also had a driving school, the École de Pilotage Winfield, run by the Knight brothers and Simon Delatour, that honed the talents of people such as France's first (and so far only) Formula One World Champion Alain Prost, and Grand Prix winners Didier Pironi and Jacques Laffite. The event was run at the new fast, up-and-down Prenois circuit near Dijon in 1974, before returning to Ricard in 1975 and 1976. The race was originally scheduled to be run at Clermont-Ferrand for 1974 and 1975, but the circuit was deemed too dangerous for Formula One. The two venues alternated the venue until 1984, with Ricard getting the race in even-numbered years and Dijon in odd-numbered years (except 1983). 1977 saw a new part of the Dijon circuit built called the "Parabolique". This was done to increase lap times which had been very nearly below a minute in 1974, and the race featured a battle between American Mario Andretti and Briton John Watson; Andretti came out on top to win. Lotus teammates Andretti and Swede Ronnie Peterson dominated the race in 1978 with their dominant 79s, a car that dominated the field in a way not seen since the dominating Alfa Romeo and domineering Ferrari in the early 1950s. The 1979 race was another classic, with the famous end-of-race duel for second place between Frenchman René Arnoux in a 1.5-liter turbocharged V6 Renault and Canadian Gilles Villeneuve in a 3-liter Flat-12 Ferrari. It is considered to be one of the all-time great duels in motorsports, with Arnoux and Villeneuve banging wheels and cars around the fast Dijon circuit before Villeneuve came out on top. The race was won by Arnoux's French teammate Jean-Pierre Jabouille, which was the first race ever won by a Formula One car with a turbo-charged engine. 1980 saw rookie Prost qualify his slower McLaren seventh and Australian Alan Jones beat French Ligier drivers Laffite and Pironi on their home soil, and the 1981 race was the first of 51 victories by future 4-time world champion Prost; driving a Renault, the French marque won the next three French Grands Prix. The 1982 event at Ricard was a memorable one for France – it was a turbo-charged engine/French walkover and 4 French drivers finished in the top 4 positions – each of them driving a car with a turbo-charged engine. Renault driver René Arnoux won from his teammate Prost and Ferrari drivers Pironi and Patrick Tambay finished 3rd and 4th. But this French triumph was internally sour: Arnoux violated an agreement that if he was in front of Prost, he would let him by because Prost was better placed in the championship. Much to the chagrin of Prost and the French Renault team's management Arnoux did not do this, despite the management holding out pit boards ordering him to let Prost past. Prost won the next year at the same place, beating out Nelson Piquet in a Brabham with a turbocharged BMW engine; Piquet had led the previous year's race but retired with engine failure.

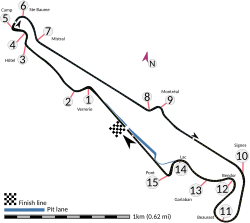

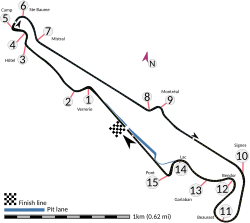

Dijon was last used in 1984, and by then turbo-charged engines were almost ubiquitous, save the Tyrrell team who were still using the Cosworth V8 engine. The international motorsports governing body at the time, FISA, had instituted a policy of long-term contracts with only one circuit per Grand Prix. The choice was between Dijon and Ricard – the small Prenois circuit had cars lapping in the 1 minute 1 second range, and Ricard was the main testing facility for Formula One at the time. So it was Ricard that was chosen, and it hosted the race from 1985 to 1990. From 1986 onwards Formula One used a shortened version of the circuit, after Elio de Angelis's fatal crash at the fast Verriere bends. De Angelis was not injured by the crash, however his car caught fire and there were no marshals to help him as it was a test session, and he died of smoke inhalation in hospital the next day. These two fast corners and the whole top section of the circuit was not used for the last five races. Prost won the final three races there, the 1988 one being a particularly dramatic win; he overtook his teammate Ayrton Senna at the Curbe de Signes at the end of the ultra fast Mistral Straight and held onto the lead all the way to the finish, and the 1990 (by which time turbo-charged engines had been banned) event was led for more than 60 laps by Italian Ivan Capelli and Brazilian Maurício Gugelmin in underfunded, Adrian Newey designed Leyton-House cars – two cars that had failed to qualify at the previous event in Mexico. Prost, now driving for Ferrari after driving for McLaren from 1984 to 1989, made a late-race charge and passed Capelli to take the victory; Gugelmin had retired earlier.

Magny-Cours (1991–2008)

[edit]

In 1991, the race moved to the Circuit de Nevers Magny-Cours, where it stayed for another 17 years. Magny-Cours was the seventh venue to host the French Grand Prix as a part of the Formula One World Championship,[2] and the sixteenth in total.[3] The move to Magny-Cours was an attempt to stimulate the economy of the area, but many within Formula One complained about the remote nature of the circuit. Highlights of Magny-Cours's time hosting the French Grand Prix include Prost's final of six wins on home soil in 1993, and Michael Schumacher's securing of the 2002 championship after only 11 races. The 2004 and 2005 races were in doubt because of financial problems and the addition of new circuits to the Formula One calendar. These races went ahead as planned, but it still had an uncertain future.

In 2007 it was announced by the FFSA, the race promoter, that the 2008 French Grand Prix was put on an indefinite "pause". This suspension was due to the financial situation of the circuit, known to be disliked by many in F1 due to the circuit's location.[4] Then Bernie Ecclestone confirmed (at the time) that the 2007 French Grand Prix would be the last to be held at Magny-Cours.[5] This turned out not to be true, because funding for the 2008 race was found, and this race at Magny-Cours was the last French Grand Prix for 10 years.

Absence (2009-2017)

[edit]After various negotiations, the future of the race at Magny-Cours took another turn, with increased speculation that the 2008 French Grand Prix would return, with Ecclestone himself stating "We're going to maybe resurrect it for a year, or something like that".[6] On 24 July, Ecclestone and the French Prime Minister met and agreed to possibly maintain the race at Magny Cours for 2008 and 2009.[7] The change in fortune was completed on July, when the FIA published the 2008 calendar with a 2008 French Grand Prix scheduled at Magny-Cours once again.[8] The 2009 race, however, was again cancelled on 15 October 2008, with the official website citing "economic reasons".[9] A huge makeover of Magny-Cours ("2.0") was planned,[10][11] but cancelled in the end. The race's promoter FFSA then started looking for an alternative host. There were five different proposals for a new circuit: in Rouen with 3 possible layouts (a street circuit, in the dock area, or a permanent circuit near the airport),[12][13] a street circuit located near Disneyland Resort Paris,[14][15] Versailles,[16][17] and in Sarcelles (Val de France),[18] but all were cancelled. A final location in Flins-Les Mureaux, near the Flins Renault Factory was being considered[19] however that was cancelled as well on 1 December 2009.[20] In 2010 and 2011, there was no French Grand Prix on the Formula 1 calendar, although the Circuit Paul Ricard was a candidate for 2012.[21]

10 French drivers have won the French Grand Prix; 7 before World War I and II and 3 during the Formula One championship. French driver Alain Prost won the race six times at three different circuits; however German driver Michael Schumacher has won eight times – the joint most anybody has ever won any Grand Prix (Lewis Hamilton has since won the British and Hungarian Grands Prix eight times). Monégasque driver Louis Chiron won it five times, and the Argentine driver Juan Manuel Fangio and British driver Nigel Mansell both won four times.

Return to Le Castellet (2018-2019, 2021-2022)

[edit]In December 2016, it was confirmed that the French Grand Prix would return in 2018 at the Circuit Paul Ricard and it held a contract to host the French Grand Prix until 2022.[22][23][24] In an announcement to the nation on 13 April 2020, Emmanuel Macron, the French president, said that restrictions on public events as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic would continue until mid-July, putting the 2020 French Grand Prix, scheduled for 28 June, at risk of postponement.[25] The race was later cancelled with no intention to reschedule for the 2020 championship.[26] The race returned for the 2021 season.

The promoters of the French Grand Prix confirmed that the race was not going to be on the 2023 calendar, stating that they aim for a rotational race deal, sharing its slot with other Grands Prix.[27]

Winners of the French Grand Prix

[edit]Repeat winners (drivers)

[edit]Drivers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in 2026.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship or any of the above mentioned championships.

| Wins | Driver | Years |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | 1994, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2006 | |

| 6 | 1981, 1983, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1993 | |

| 5 | 1931,[2] 1934, 1937, 1947, 1949 | |

| 4 | 1950, 1951[3], 1954, 1957 | |

| 1986, 1987, 1991, 1992 | ||

| 3 | 1960, 1966, 1967 | |

| 1969, 1971, 1972 | ||

| 2 | 1912, 1913 | |

| 1908, 1914 | ||

| 1907, 1922 | ||

| 1925, 1927 | ||

| 1928, 1929 | ||

| 1924, 1933 | ||

| 1936, 1948 | ||

| 1953, 1958 | ||

| 1962, 1964 | ||

| 1963, 1965 | ||

| 1973, 1974 | ||

| 1975, 1984 | ||

| 1977, 1978 | ||

| 2018, 2019 | ||

| 2021, 2022 | ||

| Sources:[28][29] | ||

^ Louis Chiron won the 1931 race, but shared the win with Achille Varzi.

^ Juan Manuel Fangio won the 1951 race, but shared the win with Luigi Fagioli.

Repeat winners (constructors)

[edit]Teams in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in 2026.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship or any of the above mentioned championships.

| Wins | Constructor | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | 1952, 1953, 1956, 1958, 1959, 1961, 1968, 1975, 1990, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008 | |

| 8 | 1980, 1986, 1987, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1996, 2003 | |

| 7 | 1963, 1965, 1970, 1973, 1974, 1977, 1978 | |

| 1908, 1914, 1935, 1938, 1954, 2018, 2019 | ||

| 6 | 1926, 1928, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1936 | |

| 1924, 1932, 1934, 1948, 1950, 1951 | ||

| 1906, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1983, 2005 | ||

| 5 | 1976, 1984, 1988, 1989, 2000 | |

| 4 | 1964, 1966, 1967, 1985 | |

| 2 | 1912, 1913 | |

| 1907, 1922 | ||

| 1925, 1927 | ||

| 1947, 1949 | ||

| 1933, 1957 | ||

| 1971, 1972 | ||

| 1994, 1995 | ||

| 2021, 2022 | ||

| Sources:[28][29] | ||

Repeat winners (engine manufacturers)

[edit]Manufacturers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in 2026.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship or any of the above mentioned championships.

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 17 | 1952, 1953, 1956, 1958, 1959, 1961, 1968, 1975, 1990, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008 | |

| 11 | 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1980, 1994 | |

| 1906, 1979, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1995, 1996, 2005 | ||

| 8 | 1908, 1914, 1935, 1938, 1954, 2000, 2018, 2019 | |

| 6 | 1926, 1928, 1929, 1930, 1931, 1936 | |

| 1924, 1932, 1934, 1948, 1950, 1951 | ||

| 5 | 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 2021 | |

| 4 | 1960, 1963, 1964, 1965 | |

| 2 | 1912, 1913 | |

| 1907, 1922 | ||

| 1925, 1927 | ||

| 1947, 1949 | ||

| 1933, 1957 | ||

| 1966, 1967 | ||

| 1985, 2003 | ||

| Sources:[28][29] | ||

* Built by Cosworth, funded by Ford.

** Built by Ilmor in 2000, funded by Mercedes.

By year

[edit]

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship or any of the above mentioned championships.

- ^ Two races which can be considered to be French Grand Prix were held in 1949. The race at Saint-Gaudens was organised by the ACF like all other French Grands Prix up to 1967, but was held for Sports Cars, whereas the race at Reims was organised as an alternative, and featured a much stronger grid.

Races sometimes considered to be French Grand Prix

[edit]Beginning in the early 1920s, French media represented eight races held in France before 1906 as being Grands Prix de l'Automobile Club de France, leading to the first French Grand Prix being known as the ninth Grand Prix de l'ACF. This was done to give the Grand Prix the appearance of being the world's oldest motor race.[31] The winners of these races, along with their original titles, are listed here.

References

[edit]- ^ Grand Prix century – The Telegraph, 10 June 2006

- ^ Smith, Damien (25 June 2018). "The 7 post‑war French Grand Prix venues". Goodwood Road & Racing Club. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "French Grand Prix: Adding To The History Of F1's Oldest Race". Pirelli. 15 June 2021. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ ITV-F1.com Archived 11 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine 2008 French Grand Prix "Pause"

- ^ ITV-F1.com Archived 2 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine Ecclestone Confirms Magny Cours Departure

- ^ ITV-F1.com Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine Magny-Cours set for reprieve

- ^ BBC Sport Formula One hope for French Grand Prix

- ^ "FIA reveals 18-race calendar for 2008". formula1.com. 27 July 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ^ "Grand Prix de France – Formule 1 : 28 juin 2009". Gpfrancef1.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "19 June 2008". Grandprix.com. 19 June 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "automobilsport.comautomobilsport.com 20 June 2008". Automobilsport.com. Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "20 June 2008". Motorlegend.com. 20 June 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ [1] grandprix.com 19 June 2008

- ^ "Euro Disney the next venue for French GP?". Asiaone.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ Noah Joseph (21 November 2008). "Disney Grand Prix plans shelved". Autoblog.com. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Versailles possible for French GP". Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ^ "december 11 2007". Grandprix.com. 11 December 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Sarcelles bidding for a Grand Prix". Grandprix.com. 17 September 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ "More details emerge from Flins-Mureaux". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 16 March 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ^ Noble, Jonathan (1 December 2009). "French GP plans suffer fresh blow". autosport.com. Haymarket Publications. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ "Paul Ricard Confirme sa Candidature pour 2011". Autonewsinfo.com. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ Billiotte, Julien (5 December 2016). "Le Grand Prix de France confirmé au Ricard – F1i.com". F1i.com (in French). Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Benson, Andrew (5 December 2016). "French Grand Prix returns for 2018 after 10-year absence". BBC Sport. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ Balfour, Andrew (1 February 2019). "Race Facts - French Grand Prix". F1Destinations.com. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Formula 1: French Grand Prix set to be postponed because of the coronavirus crisis". BBC Sport. 13 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ "Formula 1 plan to start season in Austria as French GP called off". BBC Sport. 27 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "French GP promoter aims for F1 return after 2023 on "rotation" deal". Racefans. 25 August 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d "French GP". ChicaneF1. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

"ACF GP". ChicaneF1. Retrieved 9 December 2021. - ^ a b c d Higham, Peter (1995). "French Grand Prix". The Guinness Guide to International Motor Racing. London, England: Motorbooks International. pp. 367–368. ISBN 978-0-7603-0152-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ de Menezes, Jack (27 April 2020). "French Grand Prix the 10th F1 race to be called off". The Independent. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ Hodges, David (1967). The French Grand Prix.

- ^ Diepraam, Mattijs; Muelas, Felix. "Grand Prix winners 1894–2019". Forix. Autosport. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

External links

[edit]French Grand Prix

View on GrokipediaThe French Grand Prix (Grand Prix de France) is a motor racing event first held on 26 and 27 June 1906 over a 103-kilometer triangular course on public roads near Le Mans, organized by the Automobile Club de France and recognized as the inaugural automobile Grand Prix.[1][2] Won by Ferenc Szisz driving a Renault AK, the race covered 1,238 kilometers across two days and established benchmarks for endurance, speed, and engineering in motorsport.[3] Incorporated into the Formula One World Championship from its debut season in 1950, the French Grand Prix featured in 70 editions until its exclusion after the 2022 race at Circuit Paul Ricard, having rotated among seven primary circuits including Reims-Gueux's high-speed layout and Magny-Cours's flowing design.[4][5] This nomadic history reflected France's diverse racing heritage, from pre-war road races to post-war permanent facilities, fostering advancements like aerodynamic testing and turbocharger introductions in the 1970s.[5][6] Key achievements include six pre-championship victories for Bugatti and Renault each, alongside Formula One triumphs by French icons like Alain Prost, who secured four wins, and Renault's team successes amid the turbo era.[7] Controversies arose from fatal accidents, such as those at Rouen-Les-Essarts prompting safety reforms, underscoring causal links between track configurations and driver risks that drove FIA regulations.[8] The event's intermittent modern absences, including a decade-long gap from 2009 to 2018, highlight economic and logistical challenges in sustaining European races amid global expansion.[9]

Origins and Early Development

Inception and First Edition (1906)

The inaugural Grand Prix de l'Automobile Club de France, organized by the Automobile Club de France (ACF) to promote automotive innovation and establish a definitive international racing standard surpassing events like the Gordon Bennett Cup, took place on June 26 and 27, 1906, on a closed public road circuit near Le Mans.[10][11] The event attracted 32 entries from leading manufacturers, including Renault, FIAT, Mercedes, and Darracq, reflecting France's dominant position in early automobile production with no initial restrictions on engine size or power to encourage technological competition.[12][13] The triangular circuit measured 103.18 kilometers per lap, consisting of tarred dirt roads with wooden sections in short areas, requiring competitors to complete six laps daily for a total distance of 1,238 kilometers over the two days; vehicles started at 1.5-minute intervals to manage traffic on the unpaved surface prone to dust clouds that impaired visibility.[3][10] Rules emphasized reliability and practicality, mandating a minimum vehicle weight of 1,100 kilograms, fuel consumption not exceeding 15 kilometers per liter, and designs deemed "not dangerous, easy to drive, and cheap to operate," though enforcement focused on post-race verification amid the era's rudimentary safety standards.[14][2] Hungarian driver Ferenc Szisz, a mechanic for Renault, secured victory in a Type AK model featuring a 12,986 cc inline-four engine producing approximately 105 horsepower, finishing after 12 hours and 14 minutes with an average speed of 101.53 km/h despite frequent tire failures from sharp stones and intense heat melting rubber compounds.[15][16][17] FIAT's Felice Nazzaro placed second, while only 11 cars completed the grueling event, highlighting prevalent mechanical breakdowns, overheating engines, and tire changes—issues exacerbated by the dusty terrain and lack of modern pit infrastructure.[1][11] This debut underscored the nascent risks of high-speed road racing, with no fatalities but numerous retirements due to component failures under prolonged strain.[18]Establishment as the Premier Grand Prix Event

The inaugural Grand Prix de l'Automobile Club de France, held on 26–27 June 1906 on public roads near Le Mans, established the template for premier motorsport events by prioritizing technical innovation over unrestricted power. Organized by the Automobile Club de France (ACF) as a successor to the Gordon Bennett Cup, the two-day race covered 1,238 kilometers across 12 laps of a 103-kilometer circuit, testing vehicle durability and efficiency. Regulations imposed a minimum vehicle weight of 1,000 kilograms and a fuel consumption cap of 30 liters per 100 kilometers, compelling manufacturers to optimize lightweight materials and combustion efficiency rather than relying on large engines. This formula shifted racing from endurance spectacles to engineered competitions, influencing global standards by demonstrating that constrained parameters could drive automotive progress.[13][2][19] Hungarian driver Ferenc Szisz secured victory for Renault, the event's sole French winner in 1906, highlighting the marque's engineering edge amid international entries from Fiat and Mercedes. Subsequent editions reinforced French leadership, with Peugeot claiming triumphs in 1912 and 1913 through Georges Boillot's performances, underscoring national dominance in early Grand Prix racing. These successes stemmed from investments in overhead camshaft technology and robust chassis designs, which not only yielded wins but also translated to commercial advancements, as Renault's post-1906 sales surge illustrated racing's role as a proving ground for roadworthy innovations. The ACF's rule evolution, incorporating stricter fuel and oil limits by the 1920s—such as 14 kilograms combined per 100 kilometers in select events—further professionalized the discipline, balancing speed with resource efficiency to sustain spectator interest and manufacturer participation.[19][20] The French Grand Prix's prestige solidified through its role in standardizing international racing protocols, as ACF guidelines informed the 1920s AIACR formulas that capped engine displacements at around 3 liters to curb escalating costs and speeds. Extensive media documentation and the event's annual recurrence positioned it as the archetype of Grand Prix competition, eclipsing ad-hoc international cups by fostering consistent venues, entry qualifications, and technical benchmarks. This causal framework—rooted in regulatory constraints promoting ingenuity—elevated the race as motorsport's vanguard, where empirical testing of components like magnetos and low-compression engines directly advanced broader automotive reliability.[20]Circuits and Hosting Venues

Early Public Road Circuits

The inaugural French Grand Prix in 1906 utilized a temporary circuit comprising public roads near Le Mans, forming a 103.18-kilometer loop primarily consisting of dust roads sealed with tar, which competitors lapped 12 times over two days for a total distance of 1,238.16 kilometers.[11] This layout, traversing rural areas around the Sarthe River, necessitated extensive road closures that disrupted local traffic and commerce, highlighting the logistical burdens of adapting public infrastructure for high-speed racing.[1] The event's reliance on unsealed surfaces contributed to empirical risks, including reduced visibility from dust clouds and tire damage from debris, though no major spectator incidents were recorded, underscoring the causal vulnerabilities of road racing without dedicated barriers or runoffs.[10] Subsequent editions shifted to Dieppe in 1907 and 1908, employing a 76.9-kilometer public road course that circled the coastal town, demanding 10 laps for the full race distance and attracting approximately 200,000 spectators in 1907, demonstrating the spectacle's draw despite inherent perils.[21][22] Road conditions exacerbated dangers, with tar-particles in the dust causing eye injuries and numerous tire punctures, while testing sessions saw fatalities such as British driver Ernest Hall Watt's death on July 3, 1908, from a crash into a ditch, illustrating the direct causal links between inadequate roadside protections and severe outcomes.[23][24] Critics noted the inefficiency of such elongated public circuits, which strained organizational resources for crowd control and emergency response amid frequent mechanical failures and off-road excursions.[25] The 1914 French Grand Prix returned to public roads near Lyon on a 37.631-kilometer hilly and tortuous triangular layout south of the city, covered 20 times clockwise, further emphasizing the pattern of venue rotation to accommodate subsidies while exposing participants to variable gradients and narrow passages ill-suited for racing velocities exceeding 100 km/h.[26] These early road-based events, while fostering motorsport's growth through massive attendance, revealed systemic safety shortcomings—such as proximity to unyielding obstacles and spectator encroachments—that prompted incremental improvements like rudimentary barriers in later iterations, driven by accumulating evidence of crashes and injuries rather than preemptive design.[27] The disruptions from prolonged closures and the high incidence of retirements due to road imperfections underscored the tension between spectacle and practicality in pre-permanent circuit eras.[28]Permanent Circuits: Reims, Rouen-Les-Essarts, and Charade

The Reims-Gueux circuit, located west of Reims in the Champagne region, marked the debut of a permanent venue for the French Grand Prix in 1932, utilizing a triangular layout of rural public roads spanning approximately 7.8 km initially.[29] Extensions completed in 1953 formed the classic 8.35 km configuration, featuring long straights like the Thillois straight where speeds exceeded 320 km/h, emphasizing high-velocity racing that tested engine power and driver bravery.[30] Further modifications in 1954 added chicanes and banking at the Garenne curve to manage speeds, though the track's public road base led to ongoing resurfacing challenges and vulnerability to weather.[31] The circuit hosted the Grand Prix intermittently from 1932 to 1966, with its flat, fast profile providing empirical advantages in lap times—such as Lorenzo Bandini's 1966 Formula One record of 2:11.3—but also exposing causal risks in wet conditions, as seen in the 1966 race where sudden heavy rain and lightning triggered aquaplaning, multiple spins, and a red-flagged restart after 21 laps, ultimately won by Jack Brabham amid deteriorating grip on the asphalt.[32] Rouen-Les-Essarts, near Orival in Normandy, entered the French Grand Prix calendar in 1957 on a 6.54 km layout incorporating urban and rural roads with pronounced elevation shifts up to 40 meters and tight, flowing corners like the Esses sequence, demanding precise handling over raw speed.[33] Opened in 1950 and shortened from an initial 5.1 km variant used briefly in 1952, the track underwent minimal major alterations but suffered from narrow widths and tree-lined edges that amplified crash severities, as evidenced by Jo Schlesser's fatal 1968 Honda fire on lap two, prompting its final Grand Prix that year.[34] Lap records reflected its technical demands, with Jack Brabham setting 2:11.4 in 1964 using a Brabham-Climax, averaging 179 km/h, though maintenance burdens from road wear and seasonal closures highlighted trade-offs between natural thrill and sustainable operations.[35] Charade, carved into the volcanic Puy-de-Dôme terrain near Clermont-Ferrand and opened in 1958, spanned an original 8 km path mimicking the Nürburgring's undulations with steep climbs, descents exceeding 100 meters total elevation, and blind crests over lava-strewn surfaces, fostering a compact yet punishing test of car balance and tire adhesion.[36] It hosted the French Grand Prix from 1965 to 1972, shortened to 3.98 km post-1974 for safety, with its abrasive basalt aggregate accelerating tire degradation—Chris Amon's 1972 Formula One lap averaged 167 km/h—while the layout's isolation and weather exposure, including frequent fog and rain, underscored causal engineering limits in adapting natural roads for elite competition without purpose-built infrastructure.[37] These circuits prioritized unfiltered speed and terrain realism, yielding empirical excitement like Reims' straight-line duels, but incurred high costs for resurfacing public asphalt prone to cracking and poor drainage, as rain chaos at Reims 1966 demonstrated how unchecked hydroplaning at 300 km/h amplified fatality risks, driving mid-1960s shifts toward safer, dedicated facilities while preserving competitive edges through data-informed modifications rather than blanket restrictions.[38]Later Circuits: Dijon-Prenois, Paul Ricard, and Magny-Cours

The Dijon-Prenois circuit, a purpose-built track opened in 1972 near Dijon, France, featured a 3.8 km layout characterized by fast sweeping corners, a long front straight, and significant elevation changes that created a roller-coaster effect.[39] [40] These elements provided a demanding test for Formula 1 cars, with average lap speeds reaching 144 km/h and top speeds up to 266 km/h in later configurations.[39] [41] The circuit's design emphasized high-speed stability and braking zones conducive to overtaking, though its relatively short length limited overall race variability compared to longer road courses.[39] Circuit Paul Ricard, constructed in 1969 at Le Castellet, introduced a 5.8 km Grand Prix configuration with the prominent 1.8 km Mistral straight, enabling extreme top speeds and serving as a high-velocity testing ground during the turbocharged engine era of the 1980s.[42] [43] The layout's long straights and subsequent high-speed corners like Signes allowed teams to push aerodynamic and power limits, with average speeds exceeding 160 km/h on the full straight.[44] However, the track's flat profile and expansive run-offs were critiqued for reducing the inherent risks and driver precision demanded by traditional public road venues, contributing to a perception of sterility in the F1 calendar.[45] The Circuit de Nevers Magny-Cours, redeveloped in 1991 in rural central France, hosted events on a 4.4 km flowing circuit with medium- to high-speed turns but drew persistent criticism for its remote location, which hampered accessibility via limited transport links and sparse nearby accommodations.[46] [47] This isolation led to consistently low attendance figures relative to the venue's capacity, undermining the event's atmosphere and economic viability despite the track's technical merits for overtaking in sectors like the Adelaide hairpin and tight chicanes.[7] The flat, purpose-built design further amplified complaints of monotony, as it lacked the topographic drama and variable grip of earlier French road circuits, making it less adaptable to F1's evolving emphasis on spectacle and fan engagement.[46]Absences and Interruptions

1955 Cancellation Due to Le Mans Disaster

The 1955 Le Mans disaster occurred on June 11 during the 24 Hours of Le Mans at Circuit de la Sarthe, when Pierre Levegh's Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR sports car, traveling at approximately 150 mph (240 km/h), collided with the rear of Lance Macklin's slower Austin-Healey 100, causing the Mercedes to become airborne after striking an earth bank.[48] The lightweight magnesium-alloy bodywork disintegrated on impact with protective barriers, scattering burning debris—including the engine block and other heavy components—directly into a crowded spectator area adjacent to the track, resulting in the deaths of Levegh and at least 83 spectators, with nearly 180 others injured.[49] This causal sequence, driven by the combination of high closing speeds, aerodynamic lift from the car's shape, and the use of flammable materials without adequate fragmentation containment or spectator distancing, marked the deadliest incident in motorsport history up to that point.[50] In the immediate aftermath, French authorities, citing public safety imperatives amid widespread outrage, suspended all motor racing events nationwide pending the development of new international safety regulations, effectively halting road-based competitions like the French Grand Prix scheduled for July 3 at the Reims-Gueux circuit.[51] The Automobile Club de France (ACF), organizer of the Grand Prix, initially postponed the event to September but ultimately cancelled it entirely due to the ongoing ban on public-road racing and insufficient time to implement required safeguards.[52] This decision reflected a precautionary prioritization of averting further mass-casualty risks on circuits utilizing closed public roads with minimal barriers, contrasting with the continuation of races elsewhere—such as the British Grand Prix two weeks later—where organizers conducted localized risk assessments without blanket prohibitions.[50] The French response exemplified a causal overreaction rooted in emotional public sentiment rather than calibrated empirical evaluation of racing's inherent risks versus benefits, as evidenced by the sport's subsequent safety evolutions—including improved barriers, debris containment, and track designs—that reduced per-participant fatality rates without necessitating outright bans.[49] While the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) endorsed the temporary halt and supported broader scrutiny of event protocols, no immediate global reforms were mandated; instead, the incident spurred incremental changes like enhanced spectator protections, underscoring how localized political pressures in France uniquely derailed the mid-season calendar absent comparable disruptions in less reactive jurisdictions.[51] This sole mid-calendar French Grand Prix cancellation highlighted tensions between short-term hazard aversion and long-term innovation in risk management, with data from ensuing decades affirming motorsport's capacity for safer conduct through engineering and procedural advancements rather than prohibition.[50]2009-2017 Hiatus and Underlying Causes

The French Grand Prix was absent from the Formula One calendar from 2009 to 2017 primarily due to chronic financial shortfalls at the Circuit de Nevers Magny-Cours, where the event had been held since 1991. Organizers, led by the French Automobile Sport Federation (FFSA), cited economic difficulties as the decisive factor in canceling the 2009 edition, including insufficient revenue from ticket sales and sponsorships amid declining spectator interest. Attendance at the 2008 race, the final one at Magny-Cours, drew approximately 78,000 spectators on race day, reflecting a broader trend of underwhelming turnouts that failed to cover operational expenses estimated at around €20-30 million per event, inclusive of track upgrades, security, and promoter fees to Formula One Management (FOM).[53][54][55] Underlying these issues was Magny-Cours' remote location in central France, which deterred fans and limited ancillary economic benefits, exacerbating dependency on government subsidies that averaged €2 million annually plus additional guarantees. Bernie Ecclestone, then-F1 commercial rights holder, repeatedly highlighted French disinterest, noting poor crowds and lack of commercial viability as reasons to drop the race, rather than attributing fault to F1's scheduling or fees. Post-2008 global financial crisis amplified fiscal conservatism in France, with successive governments reluctant to extend public funding for an event yielding minimal return on investment, as evidenced by low tourism spillovers and negligible boosts to local GDP relative to costs.[56][57][58] Proponents of subsidies argued the Grand Prix conferred national prestige and supported motorsport infrastructure, potentially fostering long-term industry growth in a country with significant automotive heritage. However, critics, including Ecclestone and independent analysts, countered that such arguments ignored empirical data on revenue shortfalls, with taxpayer burdens outweighing prestige absent demonstrable ROI, as private investment failed to materialize despite overtures. This organizational inertia, rather than external pressures from F1, directly precipitated the hiatus, underscoring causal failures in audience engagement and cost management over narratives blaming global circuit competition.[59][60]Post-2022 Removal from Calendar

The French Grand Prix was absent from the Formula 1 calendar starting in 2023, following the conclusion of its contract after the 2022 event at Circuit Paul Ricard. Formula 1 CEO Stefano Domenicali confirmed the removal on August 25, 2022, citing the need to prioritize calendar sustainability amid expanding global races.[61][62] The organizing body, Groupement d'Intérêt Public (GIP), accumulated debts exceeding €27 million from the 2022 race, leading to postponed dissolution proceedings in December 2022 as authorities assessed liabilities.[63] This financial shortfall, including a remaining €12 million reimbursement obligation, stemmed from operational costs outpacing revenues despite public funding.[64] Total debts reached €32 million by 2024 estimates, highlighting chronic underperformance.[65] In September 2023, the Marseille public prosecutor's office launched a probe into the GIP for alleged favoritism, misappropriation of public funds, and embezzlement, with investigations ongoing into 2024.[66] These inquiries focused on exorbitant expenditures and governance lapses under former leadership, exacerbating the event's viability issues.[67] Attendance at Paul Ricard peaked at approximately 200,000 over three days in 2022, averaging around 66,000 daily—figures deemed insufficient relative to global benchmarks for retention amid F1's shift toward high-revenue markets like the United States and Middle East.[68] Domestic factors included waning French fan engagement, compounded by the Renault Group's decision to cease in-house F1 engine production after 2025, diminishing national manufacturer leverage for hosting subsidies.[69][70] Critics, including former driver Jean Alesi, attributed deeper roots to political interference rather than circuit quality, underscoring systemic barriers to sustained interest.[71]Revivals and Modern Era

Initial Return to Paul Ricard (2018)

The French Grand Prix returned to the Formula One World Championship calendar on June 24, 2018, at Circuit Paul Ricard in Le Castellet after a 10-year hiatus, secured through a five-year hosting agreement announced on December 5, 2016.[72][73] The deal, negotiated amid Formula One's transition to Liberty Media ownership, reflected efforts to reinvigorate the sport's footprint in established European markets with strong historical fan bases, including France, where prior absences were deemed a strategic oversight by promoters.[74][75] Paul Ricard, last hosting an F1 event in 1990, implemented a hybrid circuit configuration spanning 5.842 km, blending classic sections like the 1.8 km Mistral Straight with modern safety features and over 100 possible layouts adapted for grand prix standards.[76] This setup prioritized high-speed sections but introduced challenges from newly patched asphalt areas described as "like sandpaper" for their high initial grip, contributing to variable tire behavior under load.[77] The event drew an estimated 150,000 spectators over the weekend, signaling renewed national interest and economic uplift for the Provence region, though hosting fees and infrastructure upgrades—encompassing grandstand expansions to 52,000 seats and track resurfacing—imposed significant upfront costs on organizers, balanced against intangible prestige gains and promotional tie-ins like Pirelli's title sponsorship.[78][79][80] Race conditions featured air temperatures exceeding 30°C with gusty winds up to 30 mph, prompting one-stop strategies focused on tire conservation; the smooth base asphalt generally limited degradation, but heat amplified wear in traction zones, favoring teams adept at thermal management.[81][82] Mercedes' Lewis Hamilton converted pole position into victory, completing 53 laps ahead of Red Bull's Max Verstappen, with strategic flexibility proving decisive over raw pace amid the demanding layout's low-overtaking nature.[83][84] This debut revival underscored causal trade-offs in F1's global expansion: while Liberty Media's endorsement facilitated the return to affirm France's motorsport heritage, empirical outcomes revealed setup expenses yielding short-term visibility and local pride but exposing vulnerabilities like the circuit's abrasive runoff influences on strategy, without immediate resolution to broader calendar overcrowding pressures.[75][85]Events from 2018 to 2022 and Key Outcomes

The French Grand Prix returned to the Formula 1 calendar in 2018 at Circuit Paul Ricard, marking the first event there since 1990, with approximately 150,000 spectators attending over the weekend despite organizational challenges including severe traffic congestion that prompted over 2,000 fan complaints and promises of organizer response.[78][86] In 2019, the race highlighted tyre management issues, with blistering on front tyres affecting multiple drivers under virtual safety car periods, leading to debates on pit strategies and compound durability amid high track temperatures.[87][88] The 2020 edition was cancelled on April 27 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as French government restrictions on public gatherings extended until mid-July, rendering the June 26-28 dates unfeasible.[89][90] Capacity limits in 2021 restricted crowds to 15,000 per day across three zones, totaling around 45,000 for the weekend, reflecting ongoing pandemic protocols while the event proceeded without major disruptions.[91][92] The 2022 race saw Max Verstappen secure victory following Charles Leclerc's lap 18 crash from the lead, with attendance reaching a record 200,000 over the weekend amid reports of persistent financial deficits and organizational strains that contributed to the event's mounting operational challenges.[93][94][66]Factors Leading to 2023 Onward Suspension

The suspension of the French Grand Prix from the Formula One calendar starting in 2023 stemmed primarily from the financial insolvency of its organizing body, the Groupement d'Intérêt Public (GIP), which managed events at Circuit Paul Ricard from 2018 to 2022. The five-year contract with Formula One Management expired after the 2022 race without renewal, as cumulative public subsidies totaling €101.5 million across four editions—averaging over €25 million annually—failed to offset escalating operational costs, sponsor revenue shortfalls, and a reported €27 million debt accumulated by the GIP. This debt, tied to hosting fees and infrastructure demands, prompted the postponement of the GIP's planned dissolution from December 2022 and led to the withdrawal of municipal partners, such as the city of Nice, after settling related obligations. Contributing to the revenue deficits were metrics indicating diminished national interest, including a sharp decline in television viewership from approximately 8 million on free-to-air broadcaster TF1 in prior eras to 750,000 on pay-TV channel Canal+ by 2020, reflecting broader audience fragmentation and reduced commercial appeal. Weekend attendance at Paul Ricard, reaching around 200,000 for the 2022 event, proved insufficient relative to Formula One's rising hosting fees, which collectively exceeded $700 million annually across the calendar by that year. An ongoing French government investigation into the GIP's management has highlighted operational inefficiencies, further eroding viability. Perspectives on causation vary: organizers and defenders have cited Formula One's aggressive fee increases as a key barrier, paralleling strains on other European races amid competition from higher-paying emerging markets in Asia and the Middle East. Critics, however, emphasize internal mismanagement and lack of sustained national commitment, as articulated by former driver Jean Alesi, who attributed the outcome to insufficient "national will" for annual organization despite France's motorsport heritage. These factors collectively rendered continuation economically untenable without substantial restructuring.Winners and Statistical Records

Comprehensive List by Year

The French Grand Prix formed part of the Formula One World Championship calendar from 1950 to 2008, with revivals from 2018 to 2022, excluding the 1955 cancellation and 2009–2017 hiatus.[95][96] The event rotated among circuits including Reims-Gueux, Rouen-Les-Essarts, Charade (Clermont-Ferrand), Bugatti Circuit (Le Mans), Paul Ricard (Le Castellet), Dijon-Prenois, and Magny-Cours.[95] Key results for each championship edition are detailed in the table below, encompassing date, circuit, pole position holder, winner, constructor, lap count, and finishing time or margin to second place. Data draws from official race records.| Year | Date | Circuit | Pole Position | Winner | Constructor | Laps | Winning Time/Margin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 2 July | Reims-Gueux | Juan Manuel Fangio | Juan Manuel Fangio | Alfa Romeo | 64 | 2:44:16.3 |

| 1951 | 1 July | Reims-Gueux | José Froilán González | Luigi Fagioli | Alfa Romeo | 72 | 3:00:45.2 |

| 1952 | 6 July | Rouen-Les-Essarts | Alberto Ascari | Alberto Ascari | Ferrari | 40 | 2:29:27.0 |

| 1953 | 5 July | Reims-Gueux | Mike Hawthorn | Mike Hawthorn | Ferrari | 60 | 2:44:41.0 |

| 1954 | 4 July | Reims-Gueux | José Froilán González | José Froilán González | Maserati | 64 | 2:22:32.3 |

| 1956 | 1 July | Reims-Gueux | Juan Manuel Fangio | Peter Collins | Ferrari | 64 | 2:18:36.6 |

| 1957 | 7 July | Rouen-Les-Essarts | Jean Behra | Jean Behra | Maserati | 44 | 2:14:13.6 |

| 1958 | 6 July | Reims-Gueux | Mike Hawthorn | Mike Hawthorn | Ferrari | 50 | 2:10:12.2 |

| 1959 | 5 July | Reims-Gueux | Juan Manuel Fangio | Tony Brooks | Ferrari | 50 | 2:06:15.3 |

| 1960 | 3 July | Reims-Gueux | Jack Brabham | Jack Brabham | Cooper-Climax | 50 | 2:12:30.7 |

| 1961 | 2 July | Reims-Gueux | Wolfgang von Trips | Giancarlo Baghetti | Ferrari | 52 | 2:14:30.6 |

| 1962 | 8 July | Rouen-Les-Essarts | Graham Hill | Dan Gurney | Porsche | 40 | 1:56:32.6 |

| 1963 | 30 June | Reims-Gueux | Jim Clark | Jim Clark | Lotus-Climax | 53 | 2:20:13.7 |

| 1964 | 28 June | Rouen-Les-Essarts | Dan Gurney | Dan Gurney | Brabham-Climax | 40 | 1:49:42.3 |

| 1965 | 4 July | Charade | Jim Clark | Jim Clark | Lotus-Climax | 34 | 1:59:14.0 |

| 1966 | 3 July | Reims-Gueux | Jack Brabham | Jack Brabham | Brabham-Repco | 55 | 1:55:13.1 |

| 1967 | 2 July | Charade (Bugatti) | Jack Brabham | Jack Brabham | Brabham-Repco | 34 | 1:59:09.1 |

| 1968 | 7 July | Rouen-Les-Essarts | Jacky Ickx | Jacky Ickx | Ferrari | 40 | 1:45:00.1 |

| 1969 | 6 July | Charade | Jacky Ickx | Jackie Stewart | Matra-Ford | 39 | 1:55:54.7 |

| 1970 | 5 July | Charade | Jochen Rindt | Jochen Rindt | Lotus-Ford | 38 | 1:49:09.1 |

| 1971 | 4 July | Paul Ricard | Jackie Stewart | Jackie Stewart | Tyrrell-Ford | 55 | 1:42:02.3 |

| 1972 | 2 July | Charade | Jackie Stewart | Jackie Stewart | Tyrrell-Ford | 37 | 1:38:06.3 |

| 1973 | 1 July | Paul Ricard | Ronnie Peterson | Ronnie Peterson | Lotus-Ford | 54 | 1:42:15.3 |

| 1974 | 7 July | Dijon-Prenois | Niki Lauda | Ronnie Peterson | Lotus-Ford | 52 | 1:31:43.7 |

| 1975 | 6 July | Paul Ricard | Niki Lauda | Niki Lauda | Ferrari | 54 | 1:40:29.5 |

| 1976 | 4 July | Paul Ricard | Niki Lauda | James Hunt | McLaren-Ford | 54 | 1:41:23.8 |

| 1977 | 3 July | Dijon-Prenois | Mario Andretti | Mario Andretti | Lotus-Ford | 53 | 1:33:20.0 |

| 1978 | 2 July | Paul Ricard | Mario Andretti | Jean-Pierre Jabouille | Renault | 54 | 1:40:28.7 |

| 1979 | 1 July | Dijon-Prenois | Jean-Pierre Jabouille | Jean-Pierre Jabouille | Renault | 80 | 1:28:23.73 |

| 1980 | 29 June | Paul Ricard | René Arnoux | Alan Jones | Williams-Ford | 54 | 1:39:25.94 |

| 1981 | 5 July | Dijon-Prenois | Alain Prost | Alain Prost | Renault | 54 | 1:24:19.10 |

| 1982 | 25 July | Paul Ricard | Didier Pironi | René Arnoux | Ferrari | 53 | 1:35:07.87 |

| 1983 | 17 April | Paul Ricard | Alain Prost | Alain Prost | Renault | 53 | 1:35:25.19 |

| 1984 | 20 May | Dijon-Prenois | Keke Rosberg | Niki Lauda | McLaren-TAG | 52 | 1:22:18.88 |

| 1985 | 7 July | Paul Ricard | Nelson Piquet | Nelson Piquet | Brabham-BMW | 53 | 1:34:18.338 |

| 1986 | 6 July | Paul Ricard | Nigel Mansell | Nigel Mansell | Williams-Honda | 80 | 1:42:14.941 |

| 1987 | 5 July | Paul Ricard | Nigel Mansell | Nigel Mansell | Williams-Honda | 65 | 1:36:10.313 |

| 1988 | 3 July | Paul Ricard | Ayrton Senna | Alain Prost | McLaren-Honda | 65 | 1:34:56.422 |

| 1989 | 9 July | Paul Ricard | Nigel Mansell | Alain Prost | McLaren-Honda | 65 | 1:34:54.808 |

| 1990 | 8 July | Paul Ricard | Ayrton Senna | Alain Prost | Ferrari | 67 | 1:34:36.259 |

| 1991 | 7 July | Magny-Cours | Ayrton Senna | Nigel Mansell | Williams-Renault | 72 | 1:25:26.513 |

| 1992 | 5 July | Magny-Cours | Nigel Mansell | Nigel Mansell | Williams-Renault | 72 | 1:28:28.147 |

| 1993 | 4 July | Magny-Cours | Michael Schumacher | Alain Prost | Williams-Renault | 72 | 1:29:24.774 |

| 1994 | 3 July | Magny-Cours | Michael Schumacher | Michael Schumacher | Benetton-Ford | 72 | 1:30:03.610 |

| 1995 | 2 July | Magny-Cours | Damon Hill | Michael Schumacher | Benetton-Renault | 72 | 1:29:07.913 |

| 1996 | 30 June | Magny-Cours | Jacques Villeneuve | Damon Hill | Williams-Renault | 72 | 1:31:31.213 |

| 1997 | 29 June | Magny-Cours | Heinz-Harald Frentzen | Michael Schumacher | Ferrari | 72 | 1:38:50.492 |

| 1998 | 28 June | Magny-Cours | Michael Schumacher | Michael Schumacher | Ferrari | 72 | 1:30:33.660 |

| 1999 | 27 June | Magny-Cours | Heinz-Harald Frentzen | Heinz-Harald Frentzen | Jordan-Mugen-Honda | 72 | 1:34:44.049 |

| 2000 | 2 July | Magny-Cours | Michael Schumacher | David Coulthard | McLaren-Mercedes | 72 | 1:25:44.515 |

| 2001 | 1 July | Magny-Cours | Michael Schumacher | Michael Schumacher | Ferrari | 72 | 1:33:38.228 |

| 2002 | 30 June | Magny-Cours | Juan Pablo Montoya | Michael Schumacher | Ferrari | 72 | 1:25:52.979 |

| 2003 | 6 July | Magny-Cours | Kimi Räikkönen | Ralf Schumacher | Williams-BMW | 70 | 1:24:38.999 |

| 2004 | 4 July | Magny-Cours | Michael Schumacher | Michael Schumacher | Ferrari | 70 | 1:28:17.170 |

| 2005 | 3 July | Magny-Cours | Fernando Alonso | Fernando Alonso | Renault | 70 | 1:22:16.637 |

| 2006 | 2 July | Magny-Cours | Michael Schumacher | Fernando Alonso | Renault | 70 | 1:23:24.644 |

| 2007 | 1 July | Magny-Cours | Kimi Räikkönen | Kimi Räikkönen | Ferrari | 70 | 1:22:21.582 |

| 2008 | 29 June | Magny-Cours | Felipe Massa | Felipe Massa | Ferrari | 70 | 1:26:54.161 |

| 2018 | 24 June | Paul Ricard | Sebastian Vettel | Lewis Hamilton | Mercedes | 53 | 1:28:01.360 |

| 2019 | 23 June | Paul Ricard | Lewis Hamilton | Lewis Hamilton | Mercedes | 53 | 1:30:15.910 |

| 2021 | 4 July | Paul Ricard | Lewis Hamilton | Max Verstappen | Red Bull-Honda | 53 | 1:28:54.812 |

| 2022 | 24 July | Paul Ricard | Charles Leclerc | Max Verstappen | Red Bull-RBPT | 53 | 1:18:25.841 |

The table omits non-championship or disputed precursor events prior to 1950, as they lack consensus inclusion in World Championship statistics.[95] Lap counts reflect full-distance races unless shortened by weather or incidents; times include aggregate or elapsed durations per official timing.

Repeat Victors: Drivers, Constructors, and Engine Manufacturers

Michael Schumacher secured the most victories at the French Grand Prix with eight wins, spanning from 1994 to 2006, primarily during Ferrari's dominant mid-1990s to early 2000s era driven by advanced aerodynamics and engine reliability.[105] Alain Prost follows with six wins between 1981 and 1991, leveraging Renault and McLaren chassis superiority in turbocharged and aspirated engine phases.[105] Other repeat winners include Juan Manuel Fangio (three, 1950-1957), Stirling Moss (three, 1950s sports cars adapted to F1 rules), and Lewis Hamilton (three, 2018-2020), illustrating eras of technological edges rather than random variance, as repeat success correlated with constructors' overall championship contention rates exceeding 70% in those periods.[7]| Driver | Wins | Primary Eras |

|---|---|---|

| Michael Schumacher | 8 | 1994-2006 |

| Alain Prost | 6 | 1981-1991 |