Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

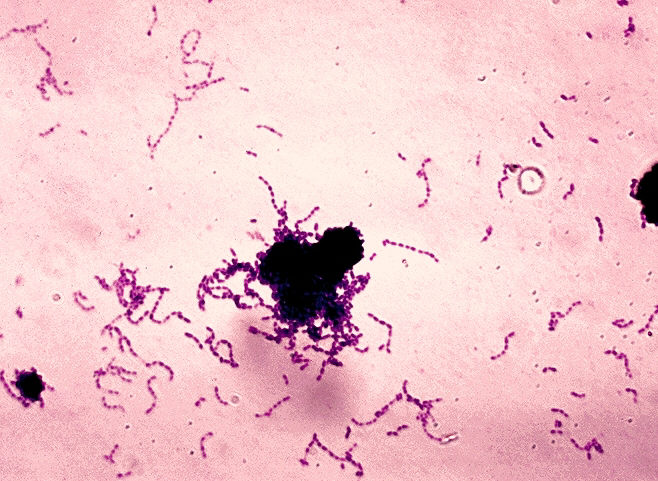

Streptococcus mutans

View on Wikipedia

| Streptococcus mutans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Stain of S. mutans in thioglycolate broth culture. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Bacillati |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Bacilli |

| Order: | Lactobacillales |

| Family: | Streptococcaceae |

| Genus: | Streptococcus |

| Species: | S. mutans

|

| Binomial name | |

| Streptococcus mutans Clarke 1924

| |

Streptococcus mutans is a facultatively anaerobic, gram-positive coccus (round bacterium) commonly found in the human oral cavity and is a significant contributor to tooth decay.[1][2] The microbe was first described by James Kilian Clarke in 1924.[3]

This bacterium, along with the closely related species Streptococcus sobrinus, can cohabit the mouth: Both contribute to oral disease, and the expense of differentiating them in laboratory testing is often not clinically necessary. Therefore, for clinical purposes they are often considered together as a group, called the mutans streptococci.[4] This grouping of similar bacteria with similar tropism can also be seen in the viridans streptococci – of which Streptococcus mutans is itself also a member.[5]

Ecology

[edit]S. mutans is naturally present in the human oral microbiota, along with at least 25 other species of oral streptococci. The taxonomy of these bacteria remains tentative.[6] Different areas of the oral cavity present different ecological niches, and each species has specific properties for colonizing different oral sites. S. mutans is most prevalent on the pits and fissures, constituting 39% of the total streptococci in the oral cavity. Fewer S. mutans bacteria are found on the buccal surface (2–9%).[7]

Bacterial-fungal co-coaggregation can help to increase the cariogenic potential of S. mutans. A symbiotic relationship with S. mutans and Candida albicans leads to increased glucan production and increased biofilm formation. This therefore amplifies the cariogenic effect of S. mutans.[8]

Oral streptococci comprise both harmless and harmful bacteria. However, under special conditions commensal streptococci can become opportunistic pathogens, initiating disease and damaging the host. Imbalances in the microbial biota can initiate oral diseases.[citation needed]

C. albicans is an opportunistic pathogenic yeast that can be found within the oral cavity.[9] Its presence in the biofilm promotes higher levels of S. mutans when looking at early childhood caries.[9] It stimulates the formation of S. mutans microcolonies.[9] This is achieved through low concentrations of cross-kingdom metabolites, such as farnesol, derived from the biofilm.[9] It has been suggested that when both microbes are present, more biofilm matrix is produced, with a greater density.[9] When farnesol is in high concentration, it inhibits the growth of both S. mutans and C. albicans.[9] This decreases the biofilm pathogenesis, and therefore its caries promoting potential.[9] This offers the potential for an anti-fungal to be used in the prevention of dental caries.[9]

Role in disease

[edit]Tooth decay

[edit]Early colonizers of the tooth surface are mainly Neisseria spp. and streptococci, including S. mutans. They must withstand the oral cleansing forces (e.g. saliva and the tongue movements) and adhere sufficiently to the dental hard tissues. The growth and metabolism of these pioneer species changes local environmental conditions (e.g., Eh, pH, coaggregation, and substrate availability), thereby enabling more fastidious organisms to further colonize after them, forming dental plaque.[10] Along with S. sobrinus, S. mutans plays a major role in tooth decay, metabolizing sucrose to lactic acid.[2][11] The acidic environment created in the mouth by this process is what causes the highly mineralized tooth enamel to be vulnerable to decay. S. mutans is one of a few specialized organisms equipped with receptors that improve adhesion to the surface of teeth. S. mutans uses the glucosyltransferase enzymes to convert the glucosyl moiety of sucrose into a sticky, extracellular, dextran-like polysaccharide that allows them to cohere, forming plaque:

- n sucrose → (glucose)n + n fructose

Sucrose is the only sugar that bacteria can use to form this sticky polysaccharide.[1]

However, other sugars—glucose, fructose, lactose—can also be digested by S. mutans, but they produce lactic acid as an end product. The combination of plaque and acid leads to dental decay.[12] Due to the role S. mutans plays in tooth decay, many attempts have been made to create a vaccine for the organism. So far, such vaccines have not been successful in humans.[13] Recently, proteins involved in the colonization of teeth by S. mutans have been shown to produce antibodies that inhibit the cariogenic process.[14] A molecule recently synthesized at Yale University and the University of Chile, called Keep 32, is supposed to be able to kill S. mutans. Another candidate is a peptide called C16G2, synthesised at UCLA.[citation needed]

It is believed that Streptococcus mutans acquired the gene that enables it to produce biofilms through horizontal gene transfer with other lactic acid bacterial species, such as Lactobacillus.[15]

Life in the oral cavity

[edit]Surviving in the oral cavity, S. mutans is the primary causal agent and the pathogenic species responsible for dental caries (tooth decay or cavities) specifically in the initiation and development stages.[16][17]

Dental plaque, typically the precursor to tooth decay, contains more than 600 different microorganisms, contributing to the oral cavity's overall dynamic environment that frequently undergoes rapid changes in pH, nutrient availability, and oxygen tension. Dental plaque adheres to the teeth and consists of bacterial cells, while plaque is the biofilm on the surfaces of the teeth. Dental plaque and S. mutans is frequently exposed to "toxic compounds" from oral healthcare products, food additives, and tobacco.[citation needed]

While S. mutans grows in the biofilm, cells maintain a balance of metabolism that involves production and detoxification. Biofilm is an aggregate of microorganisms in which cells adhere to each other or a surface. Bacteria in the biofilm community can actually generate various toxic compounds that interfere with the growth of other competing bacteria.[citation needed]

S. mutans has over time developed strategies to successfully colonize and maintain a dominant presence in the oral cavity. The oral biofilm is continuously challenged by changes in the environmental conditions. In response to such changes, the bacterial community evolved with individual members and their specific functions to survive in the oral cavity. S. mutans has been able to evolve from nutrition-limiting conditions to protect itself in extreme conditions.[18] Streptococci represent 20% of the oral bacteria and actually determine the development of the biofilms. Although S. mutans can be antagonized by pioneer colonizers, once they become dominant in oral biofilms, dental caries can develop and thrive.[18]

Cariogenic potential

[edit]The causative agent of dental caries is associated with its ability to metabolize various sugars, form a robust biofilm, produce an abundant amount of lactic acid, and thrive in the acid environment it generates.[19] A study into pH of plaque said that the critical pH for increased demineralisation of dental hard tissues (enamel and dentine) is 5.5. The Stephan curve illustrates how quickly the plaque pH can fall below 5.5 after a snack or meal.[20]

Dental caries is a dental biofilm-related oral disease associated with increased consumption of dietary sugar and fermentable carbohydrates. When dental biofilms remain on tooth surfaces, along with frequent exposure to sugars, acidogenic bacteria (members of dental biofilms) will metabolize the sugars to organic acids. Untreated dental caries is the most common disease affecting humans worldwide [21]. Persistence of this acidic condition encourages the proliferation of acidogenic and aciduric bacteria as a result of their ability to survive at a low-pH environment. The low-pH environment in the biofilm matrix erodes the surface of the teeth and begins the "initiation" of the dental caries.[19] Streptococcus mutans is a bacterium which is prevalent within the oral environment [22] and is thought to be a vital microorganism that contributes to this initiation.[23] S. mutans thrives in acidic conditions, becoming the main bacterium in cultures with permanently reduced pH [24]. If the adherence of S. mutans to the surface of teeth or the physiological ability (acidogenity and aciduricity) of S. mutans in dental biofilms can be reduced or eliminated, the acidification potential of dental biofilms and later cavity formations can be decreased.[19]

Ideally, the early various lesion is prevented via treatment from developing beyond the white spot stage. Once beyond here, the enamel surface is irreversibly damaged and cannot be biologically repaired.[25] In young children, the pain from a carious lesion can be quite distressing and restorative treatment can cause an early dental anxiety to develop.[26] Dental anxiety has knock-on effects for both dental professionals and patients. Treatment planning and therefore treatment success can be compromised. The dental staff can become stressed and frustrated when working with anxious children. This can compromise their relationship with the child and their parents.[27] Studies have shown a cycle to exist, whereby dentally anxious patients avoid caring for the health of their oral tissues. They can sometimes avoid oral hygiene and will try to avoid seeking dental care until the pain is unbearable.[28]

Susceptibility to disease varies between individuals and immunological mechanisms have been proposed to confer protection or susceptibility to the disease. These mechanisms have yet to be fully elucidated but it seems that while antigen presenting cells are activated by S. mutans in vitro, they fail to respond in vivo. Immunological tolerance to S. mutans at the mucosal surface may make individuals more prone to colonisation with S. mutans and therefore increase susceptibility to dental caries.[29]

In children

[edit]S. mutans is often acquired in the oral cavity subsequent to tooth eruption, but has also been detected in the oral cavity of predentate children. It is generally, but not exclusively, transmitted via vertical transmission from caregiver (generally the mother) to child. This can also commonly happen when the parent puts their lips to the child's bottle to taste it, or to clean the child's pacifier, then puts it into the child's mouth.[30][31]

Cardiovascular disease

[edit]S. mutans is implicated in the pathogenesis of certain cardiovascular diseases, and is the most prevalent bacterial species detected in extirpated heart valve tissues, as well as in atheromatous plaques, with an incidence of 68.6% and 74.1%, respectively.[32] Streptococcus sanguinis, closely related to S. mutans and also found in the oral cavity, has been shown to cause Infective Endocarditis.[33]

Streptococcus mutans has been associated with bacteraemia and infective endocarditis (IE). IE is divided into acute and subacute forms, and the bacterium is isolated in subacute cases. The common symptoms are: fever, chills, sweats, anorexia, weight loss, and malaise.[34]

S. mutans has been classified into four serotypes; c, e, f, and k. The classification of the serotypes is devised from the chemical composition of the serotype-specific rhamnose-glucose polymers. For example, serotype k initially found in blood isolates has a large reduction of glucose side chains attached to the rhamnose backbone. S. mutans has the following surface protein antigens: glucosyltransferases, protein antigen and glucan-binding proteins. If these surface protein antigens are not present, then the bacteria is a protein antigen-defective mutant with the least susceptibility to phagocytosis therefore causing the least harm to cells.[citation needed]

Furthermore, rat experiments showed that infection with such defective streptococcus mutants (S. mutans strains without glucosyltransferases isolated from a destroyed heart valve of an infective endocarditis patient) resulted in a longer duration of bacteraemia. The results demonstrate that the virulence of infective endocarditis caused by S. mutans is linked to the specific cell surface components present.

In addition, S. mutans DNA has been found in cardiovascular specimens at a higher ratio than other periodontal bacteria. This highlights its possible involvement in a variety of types of cardiovascular diseases, not just confined to bacteraemia and infective endocarditis.[35]

Prevention and treatment

[edit]Practice of good oral hygiene including daily brushing, flossing and the use of appropriate mouthwash can significantly reduce the number of oral bacteria, including S. mutans and inhibit their proliferation. S. mutans often live in dental plaque, hence mechanical removal of plaque is an effective way of getting rid of them.[36] The best toothbrushing technique to reduce plaque build up, decreasing caries risk, is the modified Bass technique. Brushing twice daily can help decrease the caries risk.[37] However, there are some remedies used in the treatment of oral bacterial infection, in conjunction with mechanical cleaning. These include fluoride, which has a direct inhibitory effect on the enolase enzyme, as well as chlorhexidine, which works presumably by interfering with bacterial adherence.

Furthermore, fluoride ions can be detrimental to bacterial cell metabolism. Fluoride directly inhibits glycolytic enzymes and H+ATPases. Fluoride ions also lower the pH of the cytoplasm. This means there will be less acid produced during the bacterial glycolysis.[38] Therefore, fluoride mouthwashes, toothpastes, gels and varnishes can help to reduce the prevalence of caries.[39] However, findings from investigations into the effect of fluoride-containing varnish, on the level of Streptococcus mutans in the oral environment in children suggest that the reduction of caries cannot be explained by a reduction in the level of Streptococcus mutans in saliva or dental plaque.[40] Fluoride varnish treatment with or without prior dental hygiene has no significant effect on the plaque and salivary levels of S. mutans.[41]

S. mutans secretes Glucosyltransferase on its cell wall, which allows the bacteria to produce polysaccharides from sucrose. These sticky polysaccharides are responsible for the bacteria's ability to aggregate with one another and adhere to tooth enamel, i.e. to form biofilms. Use of Anti Cell-Associated Glucosyltransferase (Anti-CA-gtf) Immunoglobulin Y disrupts S. mutans' ability to adhere to the teeth enamel, thus preventing it from reproducing. Studies have shown that Anti-CA-gtf IgY is able to effectively and specifically suppress S. mutans in the oral cavity.[42]

Other common preventative measures center on reducing sugar intake. One way this is done is with sugar replacements such as xylitol or erythritol which cannot be metabolized into sugars which normally enhance S. mutans growth. The molecule xylitol, a 5 carbon sugar, disrupts the energy production of S.mutans by forming a toxic intermediate during glycolysis.[43][44] Various other natural remedies have been suggested or studied to a degree, including deglycyrrhizinated licorice root extract,[45][46] tea tree oil,[47] macelignan (found in nutmeg),[48] curcuminoids (the main components of turmeric),[49] and eugenol (found in bay leaves, cinnamon leaves and cloves). Additionally various teas have been tested for activity against S. mutans and other dental benefits.[50][51][52][53][54] Recently, small molecule inhibitors selectively inhibit or disperse S. mutans biofilms have been identified and developed.[55][56][57][58] Additionally, structure-based drug designs have identified selective inhibitors targeting S. mutans glucosyltransferases.[59][60] These lead compounds are efficacious in preclinical animal models.[61] However, none of these remedies have been subject to clinical trials or are recommended by mainstream dental health groups to treat S. mutans.[citation needed]

The addition of bioactive glass beads to dental composites reduces penetration of S. mutans into the marginal gaps between tooth and composite.[62] They have antimicrobial properties, reducing bacterial penetration.[62] This decreases the risk of secondary caries developing, a common reason for failure of dental restorations.[62] This means that the longevity and efficacy of composite restorations may be improved.[62]

Bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) that target S. mutans have been researched. Phages have shown promise in reducing S. mutans in lab settings, potentially offering a targeted approach to caries prevention without harming the mouth's natural microbiome.[63][64][65][66] Several different phages have been found that infect S. mutans, including SMHBZ8.[65][66]

Survival under stressful conditions

[edit]Conditions in the oral cavity are diverse and complex, frequently changing from one extreme to another. Thus, to survive in the oral cavity, S. mutans must tolerate rapidly harsh environmental fluctuations and exposure to various antimicrobial agents to survive.[18] Transformation is a bacterial adaptation involving the transfer of DNA from one bacterium to another through the surrounding medium. Transformation is a primitive form of sexual reproduction. For a bacterium to bind, take up, and recombine exogenous DNA into its chromosome, it must enter a special physiological state termed "competence". In S. mutans, a peptide pheromone quorum-sensing signaling system controls genetic competence.[67] This system functions optimally when the S. mutans cells are in crowded biofilms.[68] S. mutans cells growing in a biofilm are transformed at a rate 10- to 600-fold higher than single cells growing under uncrowded conditions (planktonic cells).[67] Induction of competence appears to be an adaptation for repairing DNA damage caused by crowded, stressful conditions.[69]

Knowing about quorum-sensing gives rise to the potential development of drugs and therapies. Quorum-sensing peptides can be manipulated to cause target suicide. Furthermore, quenching quorum-sensing can lead to prevention of antibiotic resistance.[70]

Evolution

[edit]Three key traits have evolved in S. mutans and increased its virulence by enhancing its adaptability to the oral cavity: increased organic acid production, the capacity to form biofilms on the hard surfaces of teeth, and the ability to survive and thrive in a low pH environment.[71]

During its evolution, S. mutans acquired the ability to increase the amount of carbohydrates it could metabolize, and consequently more organic acid was produced as a byproduct.[72] This is significant in the formation of dental caries because increased acidity in the oral cavity amplifies the rate of demineralization of the tooth, which leads to carious lesions.[73] It is thought that the trait evolved in S. mutans via lateral gene transfer with another bacterial species present in the oral cavity. There are several genes, SMU.438 and SMU.1561, involved in carbohydrate metabolism that are up-regulated in S. mutans. These genes possibly originated from Lactococcus lactis and S. gallolyticus, respectively.[72]

Another instance of lateral gene transfer is responsible for S. mutans' acquisition of the glucosyltransferase (GTF) gene. The GTF genes found in S. mutans are most likely derived from other anaerobic bacteria found in the oral cavity, such as Lactobacillus or Leuconostoc. Additionally, the GTF genes in S. mutans display homology with similar genes found in Lactobacillus and Leuconostoc. The common ancestral gene is believed to have been used for hydrolysis and linkage of carbohydrates.[15]

The third trait that evolved in S. mutans is its ability to not only survive, but also thrive in acidic conditions. This trait gives S. mutans a selective advantage over other members of the oral microbiota. As a result, S. mutans could outcompete other species, and occupy additional regions of the mouth, such as advanced dental plaques, which can be as acidic as pH 4.0.[73] Natural selection is most likely the primary evolutionary mechanisms responsible for this trait.[citation needed]

In discussing the evolution of S. mutans, it is imperative to include the role humans have played and the co-evolution that has occurred between the two species. As humans evolved anthropologically, the bacteria evolved biologically. It is widely accepted that the advent of agriculture in early human populations provided the conditions S. mutans needed to evolve into the virulent bacterium it is today. Agriculture introduced fermented foods, as well as more carbohydrate-rich foods, into the diets of historic human populations. These new foods introduced new bacteria to the oral cavity and created new environmental conditions. For example, Lactobacillus or Leuconostoc are typically found in foods such as yogurt and wine. Also, consuming more carbohydrates increased the amount of sugars available to S. mutans for metabolism and lowered the pH of the oral cavity. This new acidic habitat would select for those bacteria that could survive and reproduce at a lower pH.[72]

Another significant change to the oral environment occurred during the Industrial Revolution. More efficient refinement and manufacturing of foodstuffs increased the availability and amount of sucrose consumed by humans. This provided S. mutans with more energy resources, and thus exacerbated an already rising rate of dental caries.[15] Refined sugar is pure sucrose, the only sugar that can be converted to sticky glucans, allowing bacteria to form a thick, strongly adhering plaque.[74]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.[page needed]

- ^ a b Loesche WJ (1996). "Ch. 99: Microbiology of Dental Decay and Periodontal Disease". In Baron S (ed.). Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. PMID 21413316.

- ^ Thomas VJ, Rose FD (1924). "Ethnic differences in the experience of pain". Social Science & Medicine. 32 (9): 1063–6. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(91)90164-8. PMC 2047899. PMID 2047899.

- ^ Newcastle University Dental School. "Streptococcus mutans and the mutans streptococci. In: The Oral Environment, online tutorial". Archived from the original on 2013-11-05. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- ^ English BK, Shenep JL (2009). "ENTEROCOCCAL AND VIRIDANS STREPTOCOCCAL INFECTIONS". Feigin and Cherry's Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Elsevier. p. 1258–1288. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4160-4044-6.50100-x. ISBN 978-1-4160-4044-6.

- ^ Nicolas GG, Lavoie MC (January 2011). "[Streptococcus mutans and oral streptococci in dental plaque]". Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 57 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1139/W10-095. PMID 21217792.

- ^ Ikeda T, Sandham HJ (October 1971). "Prevalence of Streptococcus mutans on various tooth surfaces in Negro children". Archives of Oral Biology. 16 (10): 1237–40. doi:10.1016/0003-9969(71)90053-7. PMID 5289682.

- ^ Metwalli KH, Khan SA, Krom BP, Jabra-Rizk MA (2013-10-17). "Streptococcus mutans, Candida albicans, and the human mouth: a sticky situation". PLOS Pathogens. 9 (10) e1003616. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003616. PMC 3798555. PMID 24146611.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "UTCAT3248, Found CAT view, CRITICALLY APPRAISED TOPICs". cats.uthscsa.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ Vinogradov AM, Winston M, Rupp CJ, Stoodley P (2004). "Rheology of biofilms formed from the dental plaque pathogen Streptococcus mutans". Biofilms. 1: 49–56. doi:10.1017/S1479050503001078.

- ^ "Dental Researchers to Mouth Bacteria: Don't Get too Attached". 2010-12-08.

- ^ Madigan M, Martinko J, eds. (2005). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-144329-7.[page needed]

- ^ Klein JP, Scholler M (December 1988). "Recent advances in the development of a Streptococcus mutans vaccine". European Journal of Epidemiology. 4 (4): 419–25. doi:10.1007/BF00146392. JSTOR 3521322. PMID 3060368. S2CID 33960606.

- ^ Hajishengallis G, Russell MW (2008). "Molecular Approaches to Vaccination against Oral Infections". Molecular Oral Microbiology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-24-0.

- ^ a b c Hoshino T, Fujiwara T, Kawabata S (2012). "Evolution of cariogenic character in Streptococcus mutans: horizontal transmission of glycosyl hydrolase family 70 genes". Scientific Reports. 2: 518. Bibcode:2012NatSR...2E.518H. doi:10.1038/srep00518. PMC 3399136. PMID 22816041.

- ^ Simon L (1 December 2007). "The Role of Streptococcus mutans and Oral Ecology in the Formation of Dental Caries". Journal of Young Investigators. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ Alaluusua S, Renkonen OV (December 1983). "Streptococcus mutans establishment and dental caries experience in children from 2 to 4 years old". Scandinavian Journal of Dental Research. 91 (6): 453–457. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0722.1983.tb00845.x. PMID 6581521.

- ^ a b c Biswas S, Biswas I (April 2011). "Role of VltAB, an ABC transporter complex, in viologen tolerance in Streptococcus mutans". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 55 (4): 1460–9. doi:10.1128/AAC.01094-10. PMC 3067168. PMID 21282456.

- ^ a b c Argimón S, Caufield PW (March 2011). "Distribution of putative virulence genes in Streptococcus mutans strains does not correlate with caries experience". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 49 (3): 984–92. doi:10.1128/JCM.01993-10. PMC 3067729. PMID 21209168.

- ^ "The Stephan Curve | Caries Process and Prevention Strategies: The Environment | CE Course". www.dentalcare.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2017. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- ^ Frencken JE, Sharma P, Stenhouse L, Green D, Laverty D, Dietrich T (March 2017). "Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis - a comprehensive review". Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 44 (Suppl 18): S94 – S105. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12677. PMID 28266116.

- ^ "The Role of Streptococcus mutans And Oral Ecology in the Formation of Dental Caries". Journal of Young Investigators. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ Gamboa F, Plazas L, García DA, Aristizabal F, Sarralde AL, Lamby CP, et al. (December 2018). "Presence and count of S. mutans in children with dental caries: before, during and after a process of oral health education" (PDF). Acta Odontologica Latinoamericana. 31 (3): 156–163. PMID 30829371.

- ^ Matsui R, Cvitkovitch D (March 2010). "Acid tolerance mechanisms utilized by Streptococcus mutans". Future Microbiology. 5 (3): 403–417. doi:10.2217/fmb.09.129. PMC 2937171. PMID 20210551.

- ^ Gross EL, Beall CJ, Kutsch SR, Firestone ND, Leys EJ, Griffen AL (2012-10-16). "Beyond Streptococcus mutans: dental caries onset linked to multiple species by 16S rRNA community analysis". PLOS ONE. 7 (10) e47722. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...747722G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047722. PMC 3472979. PMID 23091642.

- ^ Gao X, Hamzah SH, Yiu CK, McGrath C, King NM (February 2013). "Dental fear and anxiety in children and adolescents: qualitative study using YouTube". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 15 (2): e29. doi:10.2196/jmir.2290. PMC 3636260. PMID 23435094.

- ^ Caltabiano ML, Croker F, Page L, Sklavos A, Spiteri J, Hanrahan L, et al. (March 2018). "Dental anxiety in patients attending a student dental clinic". BMC Oral Health. 18 (1): 48. doi:10.1186/s12903-018-0507-5. PMC 5859659. PMID 29558935.

- ^ Thomson WM, Stewart JF, Carter KD, Spencer AJ (August 1996). "Dental anxiety among Australians". International Dental Journal. 46 (4): 320–4. PMID 9147119.

- ^ Butcher JP, Malcolm J, Benson RA, Deng DM, Brewer JM, Garside P, et al. (October 2011). "Effects of Streptococcus mutans on dendritic cell activation and function". Journal of Dental Research. 90 (10): 1221–7. doi:10.1177/0022034511412970. PMID 21690565. S2CID 11422268.

- ^ Berkowitz RJ (2006). "Mutans streptococci: acquisition and transmission". Pediatric Dentistry. 28 (2): 106–9, discussion 192–8. PMID 16708784.

- ^ de Abreu da Silva Bastos V, Freitas-Fernandes LB, da Silva Fidalgo TK, Martins C, Mattos CT, Ribeiro de Souza IP, et al. (February 2015). "Mother-to-child transmission of Streptococcus mutans: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Dentistry. 43 (2): 181–91. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2014.12.001. PMID 25486222.

- ^ Nakano K, Inaba H, Nomura R, Nemoto H, Takeda M, Yoshioka H, et al. (September 2006). "Detection of cariogenic Streptococcus mutans in extirpated heart valve and atheromatous plaque specimens". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 44 (9): 3313–7. doi:10.1128/JCM.00377-06. PMC 1594668. PMID 16954266.

- ^ Rao M, John G, Ganesh A, Jose J, Lalitha MK, John L (November 1990). "Infective endocarditis due to Streptococcus sanguis I occurring on a normal mitral valve". The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 38 (11): 866–8. PMID 2079476.

- ^ Heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. 1996. pp. 1723–50.

- ^ Nakano K, Nomura R, Ooshima T (2008). "Streptococcus mutans and cardiovascular diseases". Japanese Dental Science Review. 44: 29–37. doi:10.1016/j.jdsr.2007.09.001.

- ^ Finkelstein P, Yost KG, Grossman E (1990). "Mechanical devices versus antimicrobial rinses in plaque and gingivitis reduction". Clinical Preventive Dentistry. 12 (3): 8–11. PMID 2083478.

- ^ Patil SP, Patil PB, Kashetty MV (May 2014). "Effectiveness of different tooth brushing techniques on the removal of dental plaque in 6-8 year old children of Gulbarga". Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry. 4 (2): 113–6. doi:10.4103/2231-0762.138305. PMC 4170543. PMID 25254196.

- ^ Buzalaf MA, Pessan JP, Honório HM, Ten Cate JM (2011). "Mechanisms of action of fluoride for caries control". Monographs in Oral Science. 22: 97–114. doi:10.1159/000325151. ISBN 978-3-8055-9659-6. PMID 21701194.

- ^ Greig V, Conway DI (2012). "Fluoride varnish was effective at reducing caries on high caries risk school children in rural Brazil". Evidence-Based Dentistry. 13 (3): 78–79. doi:10.1038/sj.ebd.6400874. PMID 23059920.

- ^ Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Effect of a fluoride-containing varnish on Streptococcus mutans in plaque and saliva, Scandinavian journal of dental research, 1982, 90(6), 2003 Issue 3 - Zickert I, Emilson CG

- ^ Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventative Dentistry, Effect of three different compositions of topical fluoride varnishes with and without prior oral prophylaxis on Streptococcus mutans count in biofilm samples of children aged 2–8 years: A randomized controlled trial, 2019, Page: 286-291 - Sushma Yadav, Vinod Sachdev, Manvi Malik, Radhika Chopra

- ^ Nguyen SV, Icatlo FC, Nakano T, Isogai E, Hirose K, Mizugai H, et al. (August 2011). "Anti-cell-associated glucosyltransferase immunoglobulin Y suppression of salivary mutans streptococci in healthy young adults". Journal of the American Dental Association. 142 (8): 943–949. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0301. PMID 21804061.

- ^ Ly KA, Milgrom P, Rothen M (2006). "Xylitol, sweeteners, and dental caries". Pediatric Dentistry. 28 (2): 154–63, discussion 192–8. PMID 16708791.

- ^ Heinsohn T (2013). "Welchen Einfluss haben Xylit-haltige Kaugummis auf die Mundflora? Entwicklung eines quantitativen Testes zum Nachweis von Streptococcus mutans auf Basis der "Real-time"-quantitativen Polymerase-Kettenreaktion" [Xylitol-containing chewing gum and the oral bacterial flora. Development of a Quantitative Test for Streptococcus mutans on the Basis of the Real-time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction] (PDF). Junge Wissenschaft (Young Researcher) (in German). 97: 18–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ^ Ahn SJ, Cho EJ, Kim HJ, Park SN, Lim YK, Kook JK (December 2012). "The antimicrobial effects of deglycyrrhizinated licorice root extract on Streptococcus mutans UA159 in both planktonic and biofilm cultures". Anaerobe. 18 (6): 590–596. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2012.10.005. PMID 23123832.

- ^ Hu CH, He J, Eckert R, Wu XY, Li LN, Tian Y, et al. (January 2011). "Development and evaluation of a safe and effective sugar-free herbal lollipop that kills cavity-causing bacteria". International Journal of Oral Science. 3 (1): 13–20. doi:10.4248/IJOS11005. PMC 3469870. PMID 21449211.

- ^ Carson CF, Hammer KA, Riley TV (January 2006). "Melaleuca alternifolia (Tea Tree) oil: a review of antimicrobial and other medicinal properties". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 19 (1): 50–62. doi:10.1128/CMR.19.1.50-62.2006. PMC 1360273. PMID 16418522.

- ^ Rukayadi Y, Kim KH, Hwang JK (March 2008). "In vitro anti-biofilm activity of macelignan isolated from Myristica fragrans Houtt. against oral primary colonizer bacteria". Phytotherapy Research. 22 (3): 308–312. doi:10.1002/ptr.2312. PMID 17926328. S2CID 11784891.

- ^ Pandit S, Kim HJ, Kim JE, Jeon JG (June 2011). "Separation of an effective fraction from turmeric against Streptococcus mutans biofilms by the comparison of curcuminoid content and anti-acidogenic activity". Food Chemistry. 126 (4): 1565–1570. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.12.005. PMID 25213928.

- ^ Subramaniam P, Eswara U, Maheshwar Reddy KR (Jan–Feb 2012). "Effect of different types of tea on Streptococcus mutans: an in vitro study". Indian Journal of Dental Research. 23 (1): 43–48. doi:10.4103/0970-9290.99037. PMID 22842248.

- ^ Shumi W, Hossain MA, Park DJ, Park S (September 2014). "Inhibitory effects of green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) on exopolysaccharide production by Streptococcus mutans under microfluidic conditions". BioChip Journal. 8 (3): 179–86. doi:10.1007/s13206-014-8304-y. S2CID 84209221.

- ^ Manikya S, Vanishree M, Surekha R, Hunasgi S, Anila K, Manvikar V (Jan–Mar 2014). "Effect of Green Tea on Salivary Ph and Streptococcus Mutans Count in Healthy Individuals". International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 5 (1): 13–16. ISSN 2231-2250.

- ^ Awadalla HI, Ragab MH, Bassuoni MW, Fayed MT, Abbas MO (May 2011). "A pilot study of the role of green tea use on oral health". International Journal of Dental Hygiene. 9 (2): 110–116. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5037.2009.00440.x. PMID 21356006.

- ^ Stauder M, Papetti A, Daglia M, Vezzulli L, Gazzani G, Varaldo PE, et al. (November 2010). "Inhibitory activity by barley coffee components towards Streptococcus mutans biofilm". Current Microbiology. 61 (5): 417–421. doi:10.1007/s00284-010-9630-5. PMID 20361189. S2CID 19861203.

- ^ Liu C, Worthington RJ, Melander C, Wu H (June 2011). "A new small molecule specifically inhibits the cariogenic bacterium Streptococcus mutans in multispecies biofilms". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 55 (6): 2679–2687. doi:10.1128/AAC.01496-10. PMC 3101470. PMID 21402858.

- ^ Zhang Q, Ma Q, Wang Y, Wu H, Zou J (September 2021). "Molecular mechanisms of inhibiting glucosyltransferases for biofilm formation in Streptococcus mutans". International Journal of Oral Science. 13 (1): 30. doi:10.1038/s41368-021-00137-1. PMC 8481554. PMID 34588414.

- ^ Liu C, Zhang H, Peng X, Blackledge MS, Furlani RE, Li H, et al. (June 2023). "Small Molecule Attenuates Bacterial Virulence by Targeting Conserved Response Regulator". mBio. 14 (3): e0013723. doi:10.1128/mbio.00137-23. PMC 10294662. PMID 37074183.

- ^ Garcia SS, Blackledge MS, Michalek S, Su L, Ptacek T, Eipers P, et al. (July 2017). "Targeting of Streptococcus mutans Biofilms by a Novel Small Molecule Prevents Dental Caries and Preserves the Oral Microbiome". Journal of Dental Research. 96 (7): 807–814. doi:10.1177/0022034517698096. PMC 5480807. PMID 28571487.

- ^ Zhang Q, Nijampatnam B, Hua Z, Nguyen T, Zou J, Cai X, et al. (July 2017). "Structure-Based Discovery of Small Molecule Inhibitors of Cariogenic Virulence". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 5974. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.5974Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06168-1. PMC 5519559. PMID 28729722.

- ^ Nijampatnam B, Zhang H, Cai X, Michalek SM, Wu H, Velu SE (July 2018). "Inhibition of Streptococcus mutans Biofilms by the Natural Stilbene Piceatannol Through the Inhibition of Glucosyltransferases". ACS Omega. 3 (7): 8378–8385. doi:10.1021/acsomega.8b00367. PMC 6072251. PMID 30087944.

- ^ Ahirwar P, Kozlovskaya V, Nijampatnam B, Rojas EM, Pukkanasut P, Inman D, et al. (June 2023). "Hydrogel-Encapsulated Biofilm Inhibitors Abrogate the Cariogenic Activity of Streptococcus mutans". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 66 (12): 7909–7925. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00272. PMC 11188996. PMID 37285134. S2CID 259098374.

- ^ a b c d "UTCAT3251, Found CAT view, CRITICALLY APPRAISED TOPICs". cats.uthscsa.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ Fang Q, Yin X, He Y, Feng Y, Zhang L, Luo H, et al. (May 2024). "Safety and efficacy of phage application in bacterial decolonisation: a systematic review". The Lancet. Microbe. 5 (5): e489 – e499. doi:10.1016/S2666-5247(24)00002-8. PMID 38452780.

- ^ Lin Y, Zhou X, Li Y (February 2022). "Strategies for Streptococcus mutans biofilm dispersal through extracellular polymeric substances disruption". Molecular Oral Microbiology. 37 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1111/omi.12355. PMID 34727414.

- ^ a b Ben-Zaken H, Kraitman R, Coppenhagen-Glazer S, Khalifa L, Alkalay-Oren S, Gelman D, et al. (May 2021). "Isolation and Characterization of Streptococcus mutans Phage as a Possible Treatment Agent for Caries". Viruses. 13 (5): 825. doi:10.3390/v13050825. PMC 8147482. PMID 34063251.

- ^ a b Wolfoviz-Zilberman A, Kraitman R, Hazan R, Friedman M, Houri-Haddad Y, Beyth N (August 2021). "Phage Targeting Streptococcus mutans In Vitro and In Vivo as a Caries-Preventive Modality". Antibiotics. 10 (8): 1015. doi:10.3390/antibiotics10081015. PMC 8389033. PMID 34439064.

- ^ a b Li YH, Lau PC, Lee JH, Ellen RP, Cvitkovitch DG (February 2001). "Natural genetic transformation of Streptococcus mutans growing in biofilms". Journal of Bacteriology. 183 (3): 897–908. doi:10.1128/JB.183.3.897-908.2001. PMC 94956. PMID 11208787.

- ^ Aspiras MB, Ellen RP, Cvitkovitch DG (September 2004). "ComX activity of Streptococcus mutans growing in biofilms". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 238 (1): 167–74. doi:10.1016/j.femsle.2004.07.032. PMID 15336418.

- ^ Michod RE, Bernstein H, Nedelcu AM (May 2008). "Adaptive value of sex in microbial pathogens". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 267–85. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.01.002. PMID 18295550. as PDF

- ^ Leung V, Dufour D, Lévesque CM (2015-10-23). "Death and survival in Streptococcus mutans: differing outcomes of a quorum-sensing signaling peptide". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 1176. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01176. PMC 4615949. PMID 26557114.

- ^ Banas JA, Miller JD, Fuschino ME, Hazlett KR, Toyofuku W, Porter KA, et al. (January 2007). "Evidence that accumulation of mutants in a biofilm reflects natural selection rather than stress-induced adaptive mutation". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 73 (1): 357–61. Bibcode:2007ApEnM..73..357B. doi:10.1128/aem.02014-06. PMC 1797100. PMID 17085702.

- ^ a b c Cornejo OE, Lefébure T, Bitar PD, Lang P, Richards VP, Eilertson K, et al. (April 2013). "Evolutionary and population genomics of the cavity causing bacteria Streptococcus mutans". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 30 (4): 881–93. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss278. PMC 3603310. PMID 23228887.

- ^ a b Takahashi N, Nyvad B (March 2011). "The role of bacteria in the caries process: ecological perspectives". Journal of Dental Research. 90 (3): 294–303. doi:10.1177/0022034510379602. PMID 20924061. S2CID 25740861.

- ^ Darlington W (August 1979). Metabolism of sucrose by Stepococcus sanguis 804 (NCTC 10904) and its relevance to the oral environment (Ph.D Thesis). University of Glasgow.