Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Takshaka

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

| Takshaka | |

|---|---|

Idol of Takshaka at Taxakeshwar temple | |

| Devanagari | तक्षक |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Takṣaka |

| Affiliation | Nāga |

| Abode | Indrapuri |

| Genealogy | |

| Consort | Unnamed Nāgini |

| Children | Ashvasena |

Takshaka (Sanskrit: तक्षक, Takṣaka) is a Nagaraja in Hinduism and Buddhism. He is mentioned in the Hindu epic Mahabharata as well as in the Bhagavata Purana. He is described to be a king of the Nagas.

Takshaka are also known in Chinese and Japanese mythology as being one of the "eight Great Dragon Kings" (八大龍王 Hachi-dai Ryuu-ou),[1] they are the only snakes which can fly and also mentioned as the most venomous snakes, amongst Nanda (Nagaraja), Upananda, Sagara (Shakara), Vasuki, Balavan, Anavatapta and Utpala.

Hinduism

[edit]The King of the Nagas

[edit]Takshaka is mentioned as a King of the Nagas at (1,3).

Takshaka is mentioned as the friend of Indra, the king of gods, at (1-225,227,230). Takshaka, formerly dwelt in Kurukshetra and the forest of Khandava (modern-day Delhi) (1,3). Takshaka and Ashvasena were constant companions who lived in Kurukshetra on the banks of the Ikshumati (1,3). Srutasena, the younger brother of Takshaka, resided at the holy place called Mahadyumna with a view to obtaining the chiefship of the serpents (1,3). He was 4th king of Kamyaka.

Legend

[edit]According to the Shrimad Bhagavatam, Takshaka belonged to the Ikshvaku dynasty. He was a descendant of Rama. The name of Takshaka's son was Brihadbala, who was killed in battle by Abhimanyu, the son of Arjuna.

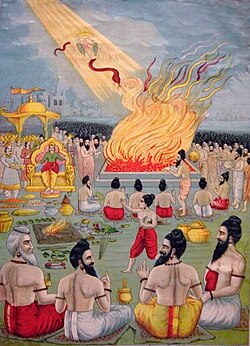

Takshaka lived in the Khandava forest (1,225). Nagas lived there with other tribes like the Pisachas, Rakshasas and Daityas and Danavas (clans of Asuras) (1,227). Arjuna burned that forest at the behest of Agni. At that time the Naga chief Takshaka was not there, having gone to Kurukshetra. But Ashvasena, the mighty son of Takshaka, was there. Arjuna slew Takshaka's wife, the mother of Ashvasena. But Ashvasena escaped (1-229,230) (4,2). To revenge upon the slaughter of his mother, Ashvasena attacked Arjuna during Kurukshetra War (8,90) (9,61), while he was battling with Karna. Ashvasena is mentioned here as born in the race of Airavata (8,90). The asura architect Mayasura who came there after Shiva warned him of the fall of Tripura is mentioned as escaping from the abode of Takshaka when Khandava Forest was burned (1,230) though some stories portray him as coming out to bow before Krishna and then guiding the Pandavas to a cave where an ancient treasure horde that also had the gandiva bow in it.

Revenge on Pandavas

[edit]

When Parikshit was cursed by a sage's son to die by a snake bite for insulting his father, Takshaka came to fulfil the curse. Takshaka did the deed by approaching in disguise (1,50) and biting Parikshit, the grandson of Arjuna and thus slaying him, while he was meditating on Lord Vishnu. He also prevented the possibility of getting any medical aid to the king, by bribing a priest in the Kasyapa clan, who was an expert in curing people from snake-poisoning (1,43).

Later King Janamejaya, the son of Parikshit, fought a war at Takshasila (1,3) and expelled the Nagas headed by Takshaka from there too.

Utanka soon became another victim while he was passing through the domain of Takshaka. By visiting Janamejaya, Utanka invoked the ire of that Kuru king, which was directed at its full force, towards Takshaka and the Naga race. Janamejaya started a campaign at Takshasila where he massacred the Nagas, with the intent of exterminating the Naga race (1,52). Takshaka left his territory and escaped to the Deva territory where he sought protection from Deva king Indra (1,53). But Janamejaya's men traced him and brought him as a prisoner in order to execute him along with the other Naga chiefs (1,56). At that time, a learned sage named Astika, a boy in age, came and interfered. His mother Manasa was a Naga and father was a Brahmin. Janamejaya had to listen to the words of the learned Astika and set Takshaka free. He also stopped the massacre of the Nagas and ended all the enmity with them (1,56). From then on, the Nagas and Kurus lived in peace. Janamejaya became a peace-loving king as well.

Other references

[edit]Takshaka, disguised as a beggar, stole the earrings of Paushya king's queen, which she had given as a gift to a Brahmin named Uttanka. Uttanka managed to get it back with the help of others. He wished to revenge on Takshaka and proceeded towards Hastinapura, the capital of Kuru king Janamejaya, the great-grandson of Arjuna. Uttanka then waited upon King Janamejaya who had some time before returned victorious from Takshashila. Uttanka reminded the king of his father Parikshit's death, at the hands of Takshaka (1,3).

In the chapters (14-53 to 58) Uttanka's history is repeated where the ear-rings were mentioned to be of queen Madayanti, the wife of king Saudasa (an Ikshwaku king) (14,57). A Naga in the race of Airavata is said to steal away the ear-rings (14,58).

- A king named Riksha in the race of Puru (a branch of Lunar Dynasty) is mentioned as marrying the daughter of a Naga in the race of Takshaka (1,95).

- Bhishma is compared in prowess to Naga Takshaka at (6,108).

- Takshaka snake means gliding snake in Hindi and Sanskrit languages.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ "Eight great dragon kings - Tibetan Buddhist Encyclopedia".

- ^ "Takshak-the flying snake". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-14. Retrieved 17 August 2014.