Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Arjuna

View on Wikipedia

| Arjuna | |

|---|---|

| Member of Pandavas | |

A statue of Arjuna in Bali | |

| Other names |

|

| Affiliation | |

| Weapon | Gandiva (bow) and arrows |

| Battles | Virata War, Kurukshetra War |

| Texts | |

| Gender | Male |

| Genealogy | |

| Born | Shatashringa forest |

| Died | |

| Parents | |

| Siblings | (half-brothers) |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Dynasty | Lunar dynasty |

Arjuna (Sanskrit: अर्जुन, IAST: Arjuna) is one of the central characters of the ancient Hindu epic Mahabharata. He is the third oldest of the five Pandava brothers and is widely recognised as the most distinguished among them. He is the son of Indra, the king of the gods, and Kunti, wife of King Pandu of Kuru dynasty—making him a divine-born hero. Arjuna is famed for his extraordinary prowess in archery and mastery over celestial weapons. Throughout the epic, Arjuna sustains a close friendship with his maternal cousin, Krishna, who serves as his spiritual guide.[1]

Arjuna is celebrated for numerous heroic exploits throughout the epic. From an early age, he distinguishes himself as an exceptional student under the tutelage of the revered warrior-sage Drona. In his youth, Arjuna secured the hand of Draupadi, the princess of Panchala, by excelling in an archery competition. Subsequently, during a period of temporary exile prompted by a breach of a fraternal agreement, Arjuna embarked on a journey during which he entered into matrimonial alliances with three princesses: Ulupi, Chitrangada, and Subhadra. From these unions, he fathered four sons: Shrutakarma, Iravan, Babhruvahana and Abhimanyu. Arjuna plays a major role in establishing his elder brother Yudhishthira’s sovereignty, subduing numerous kingdoms and setting fire to the forest of Khandavaprastha. When the Pandavas are deceitfully exiled after being tricked into forfeiting their kingdom by their jealous cousins, the Kauravas, Arjuna vows to kill Karna—a key Kaurava ally and Arjuna's main rival who is later revealed to be his elder half-brother. During exile, Arjuna undertakes a journey to acquire divine weapons and earns the favour of the god Shiva. Beyond his martial prowess, Arjuna was also skilled in music and dance, which enabled him to disguise himself as a eunuch teacher of princess Uttarā of Matsya during his final year of exile. During this period, he also defeats the entire Kuru army.

Before the Kurukshetra War, Arjuna—despite his valour—becomes deeply demoralised upon seeing his own relatives and revered teachers aligned with the opposing Kaurava side and struggled with the idea of killing them. Faced with a profound moral dilemma, he turns to Krishna, who serves as his charioteer. Krishna imparts him the knowledge of the Bhagavad Gita, counseling him on his duty (dharma) as a warrior, karma and liberation through devotion. In this moment of spiritual revelation, Arjuna is granted a vision of Krishna’s cosmic divine form, known as the Vishvarupa.[2] During the war, Arjuna—wielding the celestial bow Gandiva—emerges as a key warrior, responsible for the fall and death of several formidable foes, including Bhishma and Karna. After the war, he assists Yudhishthira in consolidating his empire through Ashvamedha. In this episode, Arjuna is slain by his own son, Babruvahana, but is revived through the intervention of Ulupi. Before the onset of the Kali Yuga, Arjuna performs the last rites of Krishna and other Yadavas. He, along with brothers and Draupadi, then undertakes his final journey to the Himalayas, where he ultimately succumbs. The Kuru dynasty continues through Arjuna's grandson, Parikshit.

Arjuna remains as an epitome of heroism, chivalry, and devotion in the Hindu tradition. He particularly holds a prominent place within the Krishna-centric Vaishnava sect of Hinduism, further elevated by his pivotal role in Bhagavad Gita, which becomes a central scripture of Hindu philosophy. Beyond the Mahabharata, Arjuna is mentioned in early works such as the Aṣṭādhyāyī (likely composed in the 5th or 6th century BCE), which mentions his worship alongside Vasudeva-Krishna,[3] as well as in the Puranas and a multitude of regional and folk traditions across India and Indonesia. His story has been an inspiration for various arts, performances and secondary literature.

Etymology and epithets

[edit]According to Monier Monier-Williams, the word Arjuna means white, clear or silver.[4] But Arjuna is known by many other names, such as:[5][6]

- Dhanañjaya (धनञ्जय) – one who conquered wealth and gold

- Guḍākesha (गुडाकेश) – one who has conquered sleep (the lord of sleep, Gudaka+isha) or one who has abundant hair (Guda-kesha).

- Vijaya (विजय) – always victorious, invincible and undefeatable

- Savyasāchī (सव्यसाची)– one who can shoot arrows using the right and the left hand with equal activity; Ambidextrous.[7]

- Shvetavāhana (श्वेतवाहन) – one with milky white horses mounted to his pure white chariot[8]

- Bībhatsu (बीभत्सु) – one who always fights wars in a fair, stylish and terrific manner and never does anything horrible in the war

- Kirīṭī (किरीटी) – one who wears the celestial diadem presented by the King of Gods, Indra[9]

- Jiṣṇu (जिष्णु) – triumphant, conqueror of enemies[10]

- Phālguṇa (फाल्गुण) – born under the star Uttara Phalguni (Denebola in Leo)[11]

- Mahābāhu (महाबाहु) – one with large and strong arms

- Gāṇḍīvadhārī (गाण्डीवधारी) – holder of a bow named Gandiva

- Pārtha (पार्थ) – son of Pritha (or Kunti) – after his mother

- Kaunteya (कौन्तेय) – son of Kunti – after his mother

- Pāṇḍuputra (पाण्डुपुत्र) – son of Pandu – after his father

- Pāṇḍava (पाण्डव) – son of Pandu – after his father

- Kṛṣṇa (कृष्ण) – He who is of dark complexion and conducts great purity.[11]

- Bṛhannalā (बृहन्नला) – another name assumed by Arjuna for the 13th year in exile

Literary background

[edit]The story of Arjuna is told in the Mahabharata, one of the Sanskrit epics from the Indian subcontinent. The work is written in Classical Sanskrit and is a composite work of revisions, editing and interpolations over many centuries. The oldest parts in the surviving version of the text may date to near 400 BCE.[12]

The Mahabharata manuscripts exist in numerous versions, wherein the specifics and details of major characters and episodes vary, often significantly. Except for the sections containing the Bhagavad Gita which is remarkably consistent between the numerous manuscripts, the rest of the epic exists in many versions.[13] The differences between the Northern and Southern recensions are particularly significant, with the Southern manuscripts more profuse and longer. Scholars have attempted to construct a critical edition, relying mostly on a study of the "Bombay" edition, the "Poona" edition, the "Calcutta" edition and the "south Indian" editions of the manuscripts. The most accepted version is one prepared by scholars led by Vishnu Sukthankar at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, preserved at Kyoto University, Cambridge University and various Indian universities.[14]

Biography

[edit]Birth and early life

[edit]Arjuna is half-divine by birth, being the son of a human queen and the king of devas (gods).[15] He is one of the five Pandava brothers, who are recognized as the sons of Pandu. However, the Pandavas were each fathered by different devas through the practice of niyoga, a custom in which a revered man may father a child on behalf of another who is deceased or incapable of procreation. Although Pandu was of royal lineage, belonging to the Lunar dynasty and having once ruled as king of the Kuru kingdom, he was rendered impotent due to a curse that would result in his death were he to engage in sexual relations.[16][note 1] To circumvent this curse, Pandu's wife Kunti utilized a sacred mantra granted to her by the sage Durvasa during her maidenhood. This mantra enabled her to invoke various gods to beget children. At Pandu’s behest, she first summoned Dharma and Vayu, resulting in the births of Yudhishthira and Bhima respectively. Each child was born a year apart. Arjuna was the third son, conceived through the invocation of the god Indra, with whom he remains connected throughout his life.[19][20]

The Adi Parva, the first book of the Mahabharata, narrates Arjuna's birth. Prior to Arjuna’s birth, Pandu deduces that he would get the best son from Indra, the Vedic storm-sky god and king of the gods, and performs intense austerities to propitiate, desiring that the king of the gods father his third. Pleased by Pandu's devotion, Indra appears before him and promises to grant a son who will achieve fame across the three worlds. When Kunti invokes Indra through the mantra, Indra, assuming human form, approaches her and begets a son. His birth is marked by the appearance of a significantly greater number of sages and celestial beings—including adityas, rudras, saptarishis, gandharvas, apsaras, etc.—compared to those present at the births of his elder brothers, indicating his far-superior prominence in the narrative. A divine voice praises him and prophesizes his future heroic deeds and names him Arjuna, while drums are heard, and flowers fall from the sky.[21][22][23] Arjuna is born under the auspicious lunar constellation of Phalguna.[24]

Arjuna, along with his two elder brothers and two younger half-brothers, is raised in the forests of Shatashringa (lit. 'hundred peaked mountain') under the care of the resident sages.[25] Following the deaths of Pandu and his second wife, Madri, Kunti returns to Hastinapura—the capital of the Kuru Kingdom—with all five sons. According to the Southern Recension of the Mahabharata, Pandu dies on Arjuna’s birthday.

Education and training

[edit]

In Hastinapura, Arjuna and his brothers are brought up alongside their paternal cousins, the Kauravas. Their early education in archery is entrusted to Kripacharya, the royal preceptor,[26] under the overall supervision of Bhishma, the grand patriarch of the Kuru dynasty.[27] Soon after, the Brahmin warrior Drona is appointed to instruct the princes in the arts of warfare and martial discipline. Upon his first encounter with them, Drona asks that they repay him a favour in the future. While the other princes remain silent, Arjuna alone gives his assent, which deeply pleases Drona. Arjuna quickly distinguishes himself as the most skilled and devoted among Drona’s pupils, eventually becoming his favourite and favoured student.[28] When Arjuna's preeminence is seemingly challenged by a tribal boy Ekalavya, Drona takes steps to ensure that Arjuna remains the greatest of his students.[29][30]

The Mahabharata presents several episodes that affirm Arjuna’s distinction as Drona’s most accomplished and devoted disciple. On one occasion, Drona is seemingly attacked by a crocodile, but Arjuna reacts the fastest, rescuing his teacher. Impressed by his presence of mind and alacrity, Drona rewards him with the Brahmashira, a powerful celestial weapon (astra). This marks the beginning of Arjuna’s acquisition of divine armaments, and it is at this moment that Drona declares, “No other man in the world will be an archer like you”.[31][28] In another episode, Drona tests the perceptiveness and concentration of his pupils through an archery trial. He places an artificial bird atop a tree and asks each student what they perceive. The princes respond by describing both the target and its surroundings, but Drona is dissatisfied with their answers. When Arjuna is questioned, he replies that he sees only the bird’s head—demonstrating absolute focus and singular vision. Drona is pleased, and this refined capacity for perception and precision becomes emblematic of Arjuna’s unique abilities.[32][note 2]

Once Drona is satisfied with the progress of his pupils, he organises a public exhibition of martial skills, attended by members of the royal court, the Kuru clan, and the citizens of Hastinapura. Arjuna makes a dramatic entrance, and Drona publicly proclaims him his favourite disciple. The crowd responds with enthusiastic acclaim, celebrating Arjuna, who demonstrates his command over divine weaponry, manipulating elemental forces such as fire, wind, water, and rain.[28] It is during this event that Karna, who later becomes Arjuna’s principal rival, first challenges him. From this moment onward, the two figures are consistently portrayed as adversaries within the epic’s narrative structure.[34][35][note 3]

The culmination of Arjuna's education is marked by his fulfilment of the teacher’s customary fee (gurudakshina), in accordance with Indian tradition. Drona requests as payment the defeat of his longstanding rival, King Drupada of Panchala. This task is accomplished collectively by the Pandavas—or, in some versions, by all of Drona's pupils. However, the Mahabharata underscores Arjuna’s central role in this achievement, also reminding that he alone, among Drona’s disciples, had pledged in advance to deliver the fee.[35][36]

Youth

[edit]Following their victory over Drupada, the Adi Parva turns to the episode of The Lacquer House Fire, a decisive moment in a series of escalating efforts by the eldest Kaurava, Duryodhana, to eliminate the Pandavas, whose talents and growing influence provoke deep resentment. In this instance, Yudhishthira discerns a veiled warning from their uncle Vidura, alerting him to a murderous plot. When the house is set ablaze, Bhima takes the lead in ensuring their survival by carrying his brothers and mother to safety through a hidden passage. Author Ruth Cecily Katz notes that Arjuna plays no notable role in this sequence, which stands in contrast to the heroism he displays elsewhere. Nevertheless, the event acts as a narrative pivot: it compels the Pandavas into exile, living in concealment under the guise of ascetic Brahmins, and paves the way for Arjuna's forthcoming feats in bride-winning that dominate the later portions of the first book.[37][38]

The Pandava brothers and their mother, Kunti, reside in concealment in a village named Ekachakra disguised as Brahmins, and lead a quiet life in exile. Upon the advice of the sage Vyasa, they decide to go to the capital of Panchala. Arjuna’s first significant challenge as a fully initiated warrior occurs during this journey when he confronts Chitraratha, a hostile gandharva—a celestial being—who poses a threat to the Pandavas. In the course of this battle, Arjuna employs the Agneyastra, the divine missile associated with fire, to destroy his opponent’s chariot. This marks the first display of Arjuna’s martial prowess in his adult life. In recognition of his defeat, the subdued gandharva offers gifts to the five brothers, bestowing upon Arjuna the particular boon of visionary insight—a faculty in which Arjuna has already shown distinction.[39]

Svayamvara and marriage to Draupadi

[edit]

Arjuna is central in the episode of svayamvara—or “bridegroom choice”—of Draupadi, the epic's heroine. Of all Arjuna’s marriages, his union with Draupadi is the most consequential for the heroic structure of the epic. It is not only the first among his four marriages but also foundational to the epic’s central conflict. The event also features first encounter between Arjuna and Krishna, who is the son of Vasudeva, Kunti's brother, making him the maternal cousin of the Pandavas.[40][41]

King Drupada, Draupadi’s father, designs the challenge for the syavamvara specifically with Arjuna in mind, having developed a strong admiration for the warrior after being defeated by him in battle. Determined to obtain Arjuna as a son-in-law, Drupada tailors the test to suit his extraordinary skills. The svayamvara features a ceremonial archery contest in which barons must perform a feat of bow-bending, a trial commonly found in Indo-European heroic marriage traditions.[40] Although the details of the contest vary across different recensions, all versions feature a target, often described as a suspended toy fish, which the suitor must strike. In more elaborate versions, which add a further degree of difficulty, the suitor is required to hit the eye of a rotating toy fish, while aiming only at its reflection in a vessel of water (or mirror) below.[42] The Pandavas attend Draupadi’s svayamvara still in disguise. Arjuna, like the other assembled nobles, is instantly captivated by the divine beauty of Draupadi at first sight. Krishna, who is present at the event as a spectator and sympathetic to the Pandavas, recognizes Arjuna. Arjuna, still in his assumed guise, successfully completes the archery challenge by striking the target with five arrows—an accomplishment in which all other princes, including renowned warriors like Duryodhana and Karna, had failed.[41][40]

This outcome provokes anger among the assembled princes, particularly the Kshatriyas who perceive the svayamvara to have been won by an unassuming brahmana. Despite his disguise, Arjuna’s exceptional skill makes it evident that he is no ordinary Brahmin. When challenged and asked to reveal his identity, Arjuna responds ambiguously, declaring only that he is “the best among fighters”. Karna, upon realizing that the victor is a Brahmin—or so he believes—chooses not to engage him further, stating that it would be improper to fight a Brahmin.[41] When Arjuna returns with Draupadi, Kunti—unaware of what exactly he has brought—unintentionally instructs her sons to share whatever has been obtained. Though spoken in ignorance, her words are interpreted as a binding directive. The situation is further complicated by Arjuna’s own refusal to marry Draupadi before his elder brother. Although Yudhishthira insists that Arjuna, having won her in the svayamvara, ought to be her husband, Arjuna declines on the grounds of seniority. This deference to fraternal hierarchy reinforces the Arjuna’ ethos of respect. Yudhishthira finally decides that she shall become the wife of all five brothers, to which they all agree. Later at the palace, Drupada joyfully welcomes the Pandavas, Kunti, and Draupadi, delighted that Arjuna has won her hand and promptly begins wedding preparations. However, upon learning she is to marry all five brothers, he vehemently objects. Vyasa intervenes, revealing that the Pandavas are partial incarnations of five Indras—Indra here being a divine office—and Draupadi is the incarnation of Shri, destined to be their common wife. After much reasoning, Drupada finally agrees, and Draupadi's wedding with each of the Pandavas is performed on successive days, with Arjuna's taking place on the third day.[43][44]

Although Draupadi becomes the wife of all five Pandava brothers, Arjuna occupies a distinct position as her principal husband. This status is supported by textual references within the Mahābhārata that suggest Draupadi favours Arjuna and holds a particular affection for him. From their union, Arjuna fathers a son—named in various sources as either Shrutakriti or Shrutakarman—who is one of the five sons Draupadi bears, one by each of the Pandavas.[45]

Pilgrimage

[edit]After their marriage to Draupadi and their survival revealed, the Pandavas are granted half the kingdom by the Kuru King Dhritarashtra.[17][18] They then establish themselves at Khandavaprastha, where they oversee the construction of a great fortified city. This settlement is subsequently identified as Indraprastha, named in honour of Arjuna’s divine father, Indra. The brothers agree upon a code of conduct concerning Draupadi: none may intrude when she is alone with another. If this rule is breached, the offender must undergo a period of exile lasting one year—or twelve years, according to certain translations[46]—during which he is required to remain celibate. Arjuna is the one who ultimately violates the agreement—unintentionally and for a justifiable cause. He enters his brother’s chamber to retrieve weapons, intending to defend the cattle of a Brahmin under threat. Although Yudhishthira offers to exempt him from the exile, Arjuna declines, choosing instead to honour the commitment. However, this vow of celibacy is broken as Arjuna marries three women during the course of his journey.[47]

Encounter with Ulupi

[edit]

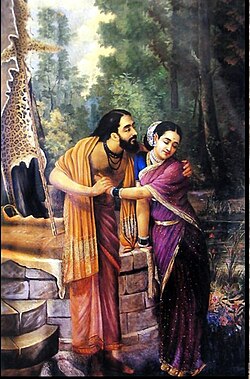

Upon leaving, Arjuna goes into pilgrimage, narrated in the Adi Parva. He eventually settles at a sacred site, Ganga-dvara, on the banks of river Ganga, where he makes offerings to his ancestors. While preparing to perform a fire ritual on the riverbank, he is suddenly seized during a bath and drawn beneath the waters by a Nāga (serpentine divine being) woman named Ulupi, who has developed a strong infatuation upon seeing him bathing in the river. In the enchanted underwater realm, Arjuna discovers a palace complete with a consecrated space where sacred fires are maintained, and it is here that he conducts a fire ceremony, or agnikarya. Ulupi, taking her human form, introduces herself as the daughter of the Nāga king Kauravya and expresses her longing for Arjuna, imploring him to have sex with her. Arjuna initially hesitates, determined to honour his vow of celibacy and explains his condition. However, Ulupi contends that his vow pertains solely to Draupadi, and declares that she would rather die than be refused. Invoking his role as protector of those in distress, Arjuna consents. Arjuna remains with Ulupi for a single night, fulfilling her desires, before continuing on his journey. Although no child is mentioned at the time of their encounter, it is later revealed that Ulupi had conceived and given birth to a son, Iravat, after Arjuna's departure. Further, Ulupi is later revealed to be a widow, when she sees first encounters Arjuna.[48][46][49]

Ulupi is not called Arjuna's "wife" until the fourteenth book of the epic, Ashvamedhika Parva, due to which few consider it as a paramour affair.[50] However, scholars state that their union is legitimised through what is traditionally identified as a gandharva marriage—a private, mutual agreement without formal rituals.[48]

Marriage to Chitrangada and tour to the south

[edit]Arjuna continues his journey eastward, undertaking a pilgrimage to various sacred sites. In the course of his travels, he arrives at Manipura (also called Manalura), the capital of King Chitravahana. There, he becomes captivated by Chitrangada, the king’s only child. As a putrika—a daughter designated to carry forward the royal lineage through her own offspring—she is raised in the manner of a son. Arjuna formally approaches King Chitravahana to request her hand in marriage. The king consents, but only on the condition that any son born of the union must remain in Manipura to succeed the throne and preserve the matrilineal succession. This stipulation, whereby the offspring is effectively offered as the bride-price, renders the marriage an asura-type. Arjuna accepts the condition without protest. He resides in Manipura for a period described as three months—or, in the versions of the twelve-year exile narrative, three years—before continuing his journey southwards.[48][51][52]

During his journey to the south, Arjuna encounters five sacred waters inhabited by cursed crocodiles that frighten away ascetics. Ignoring warnings, he enters one of the waters, and is attacked by a crocodile, which he overpowers and drags to the shore. The creature transforms into Varga, an apsara (celestial nymph), who reveals that she and four other apsaras—Saurabhi, Samichi, Budabuda and Lata—had been cursed to become crocodiles for attempting to seduce a young ascetic. Grateful for her release, Varga asks Arjuna to free her companions. He obliges, defeating the remaining crocodiles and liberating the Apsaras.[52] He then revisits Manipura and is reunited with Chitrangada and their son, Babhruvahana. However, he neither attempts to settle there permanently nor seeks to take Chitrangada with him upon his departure.[48][51][52]

Marriage to Subhadra

[edit]

Arjuna's pilgrimage goes westwards, eventually reaching the site of Prabhasa. Krishna, upon learning of Arjuna’s arrival, travels to Prabhasa to meet him. The two companions develop a strong bond.[53] Krishna then invites Arjuna to his capital Dvaraka. During a festival at Mount Raivataka, Arjuna sees Subhadra, the princess of the Vrishnis (a clan of Yadava lineage) who is also Krishna’s sister, and falls in love at first sight. Sensing his feelings, Krishna offers to intercede with their father but ultimately suggests abduction, arguing that a svayamvara would be uncertain in outcome. With Yudhishthira’s consent through messengers, Arjuna feigns a hunting trip on a chariot, seizes Subhadra on the Dwaraka–Raivataka road, and drives towards Indraprastha.[48][51][52][note 4] The Vrishnis convene in response. Balarama advocates war, but Krishna defends Arjuna’s conduct, emphasising the honour shown to their family and the political advantages of the alliance. He argues that Arjuna, recognising both the Vrishnis’ lack of greed for bride-price and the unpredictability of a bridegroom-choice ceremony, chose the most respectful course available. Krishna’s reasoning prevails, and Arjuna is invited back to Dvaraka for a formal wedding ceremony.[51][52]

The marriage with Subhadra is categorised as a rakshasa or capture-marriage—a form associated with heroic traditions across Indo-European literature. Arjuna spends the remaining period of his exile at Dvaraka, following which he returns to Indraprastha. While his brothers welcome him with his new bride, Draupadi reacts with jealousy. A reconciliation is achieved when Subhadra, on Arjuna's advice, wins over her with humility. Abhimanyu, described as Arjuna's favourite son, is born to Subhadra at Indraprastha. Although not central to the heroic arc in the way his marriage to Draupadi is, Arjuna’s union with Subhadra is of lasting importance, providing a key genealogical link in the epic’s structure, as the Kuru dynasty survives through Abhimanyu's descendants.[48]

Burning of Khandava Forest

[edit]

One of the most enigmatic and controversial episodes in Arjuna's life is the burning of the Khandava Forest, recounted at the end of the Adi Parva. By this time, Arjuna and Krishna are close companions, often referred to collectively as "the two Krishnas". While resting along the Yamuna in the company of their wives, they are approached by a brahmin who is later revealed to be Agni, the god of fire, in disguise. Agni seeks their aid in consuming the Khandava Forest—a task he has repeatedly failed to complete due to the interference of Indra, who extinguishes the flames with rain, as the forest is inhabited by Takshaka, a Naga chieftain and Indra’s close ally. Bound by the kshatriya code to honour a brahmin's request, Arjuna and Krishna agree to help Agni regardless of the consequences. As a reward, Agni instructs the water-god Varuna to bestow upon Arjuna the celestial bow Gandiva, twin quivers of inexhaustible arrows, a divine chariot, and celestial steeds. Once committed, the two proceed with ruthless efficiency. As Agni sets the forest alight, Arjuna and Krishna slaughter all fleeing creatures, including demons, Asuras, Nagas, birds and other animals, ensuring none escape the inferno. Takshaka is notably absent during the massacre, but his wife is killed and his son, Ashvasena, narrowly escapes—vowing vengeance against Arjuna. When Indra arrives, joined by other Vedic deities, Arjuna repels them all, including his own divine father. The gods retreat—having been commanded by a mysterious celestial voice to stand down and observe, while also revealing that Arjuna and Krishna are incarnations of Nara and Narayana. After six days of relentless destruction, Indra promises Arjuna further divine weaponry in gratitude.[55]

Alf Hiltebeitel describes the episode as "one of the strangest scenes of the epic".[53] Katz notes its deep ethical dissonance with the overarching philosophy of the Mahabharata. The indiscriminate slaughter of innocents, and the blatant disregard for ahimsa (nonviolence) and the rules of war, sharply contrast with the epic’s didactic tone. Krishna and Arjuna, laughing as they destroy every creature in their path, evoke a frenzied, berserker-like ideal more aligned with archaic heroism than with the dharma-centred values often upheld elsewhere in the text. The episode is thought to preserve an older stratum of mythic storytelling—parallel to traditions found in the Iliad or the Epic of Gilgamesh—where absolute, even terrifying violence is valorised when enacted in service of a divine or cosmic imperative.

The game of dice

[edit]As heir to the lordship of Kurukshetra, Yudhishthira had attracted the unwelcome attention of his Kaurava cousin, Duryodhana, who sought the throne.[56] The royal consecration involved an elaborate Vedic ceremony called rajasuya which extended over several years and included the playing of a ritualised game of dice.[57] This particular game, described as "Indian literature's most notorious dice game" by Williams,[58] was rigged by Duryodhana, causing Yudhishthira to gamble and lose everything, including his kingdom and his shared wife Draupadi.[59][60] He and his brothers only obtained their freedom because Draupadi offered herself to the Kauravas in exchange. She was then humiliated by them so much that revenge for her treatment became a further motivation for the Pandavas in the rivalry with their cousins.[59] During her humiliation, Karna called her an unchaste for marrying five men. This led Arjuna to take a vow of killing Karna.[61] The brothers, including Arjuna, were forced into a 12-year exile, to be followed by a year living incognito if Yudhishthira was to regain his kingdom.[60]

Exile of the Pandavas

[edit]While in this exile, Arjuna visited the Himalayas to get celestial weapons that he would be able to use against the Kauravas. Thereafter, he honed his battle skills with a visit to Swarga, the heaven of Indra, where he emerged victorious in a battle with the Daityas and also fought for Indra, his spiritual father, with the Gandiva.[19]

After the battle at Khandava, Indra had promised Arjuna to give him all his weapons as a boon for matching him in battle with the requirement that Shiva is pleased with him. During the exile, following the advice of Krishna to go on meditation or tapasya to attain this divine weapon, Arjuna left his brothers for a penance on Indrakeeladri Hill (Vijayawada, Andhra Pradesh).[62]

When Arjuna was in deep meditation, a wild boar ran towards him. He realized it and took out an arrow and shot it at the boar. But, another arrow had already pierced the boar. Arjuna was furious and he saw a hunter there. He confronted the hunter and they engaged in a fight. After hours of fighting, Arjuna was not able to defeat him and realized that the hunter was Shiva. Shiva was pleased and took his real form. He gave him Pashupatastra and told that the boar was Indra as he wanted to test Arjuna. After gaining the weapon, Indra took him to heaven and gave him many weapons.[62][63]

During his exile, Arjuna was invited to the palace of Indra, his father. An apsara named Urvashi was impressed and attracted to Arjuna's look and talent so she expresses her love in front of him. But Arjuna did not have any intentions of making love to Urvashi. Instead, he called her "mother". Because once Urvashi was the wife of King Pururavas the ancestor of Kuru dynasty. Urvashi felt insulted and cursed Arjuna that he will be a eunuch for the rest of his life. Later on Indra's request, Urvashi curtailed the curse to a period of one year.[64][65]

At Matsya Kingdom

[edit]

Arjuna spent the last year of exile as a eunuch named Brihannala at King Virata’s Matsya Kingdom. He taught singing and dancing to the princess Uttarā. After Kichaka humiliated and tried to molest Draupadi, Arjuna consoled her and Bhima killed Kichaka. When Duryodhana and his army attacked Matsya, Uttara, Uttarā's brother, with Brihannala as his charioteer went to the army. Later that day, the year of Agyatavasa was over. Arjuna took Uttara away from the army to the forest where he had kept his divine bow, Gandiva, and revealed his identity to Uttara. He then fought Kaurava army and single-handedly defeated them including warriors like Bheeshma, Drona, Ashwatthama, Karna, Duryodhana etc. When Arjuna's identity was revealed to the court, Uttarā was married to Arjuna's son Abhimanyu.[64][66]

Kurukshetra War

[edit]Bhagavat Gita

[edit]The Bhagavad Gita is a book within the Mahabharata that depicts a dialogue between Arjuna and Krishna immediately prior to the commencement of the Kurukshetra War between the Pandavas and Kauravas. According to Richard H. Davis,

The conversation deals with the moral propriety of the war and much else as well. The Gita begins with Arjuna in confusion and despair, dropping his weapons; it ends with Arjuna picking up his bow, all doubts resolved and ready for battle.[67]

In the war

[edit]Arjuna was a key warrior in Pandava's victory in the Kurukshetra. Arjuna's prowess as an archer was demonstrated by his success in slaying numerous warriors, including his own elder brother Karna and grandfather Bhishma.

- Fall of Bheeshma: On the 10th day of battle, Arjuna accompanied Shikhandi on the latter's chariot and they faced Bheeshma who did not fire arrows at Shikhandi but battles Arjuna. He was then felled in battle by Arjuna, pierced by innumerable arrows, piercing his entire body.[64][68]

- Death of Bhagadatta: On the 12th day of the war, Arjuna killed the powerful king of Pragjyotisha Bhagadatta, along with his mighty elephant Supratika.[69]

- Death of Jayadratha: Arjuna learns that Jayadratha blocked the other four Pandavas, at the entrance of Chakravyuha, due to which Abhimanyu entered alone and was killed unfairly by multiple Kaurava warriors on the 13th day of the war. Arjuna vowed to kill him the very next day before sunset, failing which he would kill himself by jumping into a fire. Arjuna pierced into the Kaurava army on the 14th day, killing seven akshouhinis of their army, and finally beheaded Jayadratha on the 14th day of the war.

- Death of Sudakshina: He killed Sudakshina the king of Kambojas on the 14th day using Indrastra killing him and a large part of his army. He also killed Shrutayu, Ashrutayu, Niyutayu, Dirghayu, Vinda, and Anuvinda during his quest to kill Jayadratha.

- Death of Susharma: Arjuna on the 18th day killed King Susharma of Trigarta Kingdom, the main Kaurava ally.

- Death of Karna: The much anticipated battle between Arjuna and Karna took place on the 17th day of war. The battle continued fiercely and Arjuna killed Karna by using Anjalikastra.[64][70]

Later life and death

[edit]After the Kurukshetra War, Yudhishthira appointed Arjuna as the Prime Minister of Hastinapur. Yudhishthira performed Ashvamedha. Arjuna followed the horse to the land of Manipura and encountered Babhruvahana, one of his sons. None of them knew one another. Babhruvahana asked Arjuna to fight and injured his father during the battle. Chitrāngadā came to the battlefield and revealed that Arjuna was her husband and Babhruvahana's father. Ulupi, the second wife of Arjuna, revived Arjuna using a celestial gem called Nagamani.[71]

After Krishna left his mortal body, Arjuna took the remaining citizens of Dwaraka to Indraprastha. On the way, they were attacked by a group of bandits. Arjuna desisted from fighting seeing the law of time.

Upon the onset of the Kali Yuga, and acting on the advice of Vyasa, Arjuna and other Pandavas retired, leaving the throne to Parikshit (Arjuna's grandson and Abhimanyu's son). Giving up all their belongings and ties, the Pandavas, accompanied by a dog, made their final journey of pilgrimage to the Himalayas. The listener of the Mahabharata is Janamejaya, Parikshit's son and Arjuna's great-grandson.[72]

Outside Indian subcontinent

[edit]Indonesia

[edit]

In the Indonesian archipelago, the figure of Arjuna is also known and has been famous for a long time. Arjuna especially became popular in the areas of Java, Bali, Madura and Lombok. In Java and later in Bali, Arjuna became the main character in several kakawin, such as Kakawin Arjunawiwāha, Kakawin Pārthayajña, and Kakawin Pārthāyana (also known as Kakawin Subhadrawiwāha. In addition, Arjuna is also found in several temple reliefs on the island of Java, for example the Surawana temple.

Wayang story

[edit]

Arjuna is a well-known figure in the world of wayang (Indonesian puppetry) in Javanese culture. Some of the characteristics of the wayang version of Arjuna may be different from that of Arjuna in the Indian version of the Mahābhārata book in Sanskrit. In the world of puppetry, Arjuna is described as a knight who likes to travel, meditate, and learn. Apart from being a student of Resi Drona at Padepokan Sukalima, he is also a student of Resi Padmanaba from the Untarayana Hermitage. Arjuna was a Brahman in Goa Mintaraga, with the title Bagawan Ciptaning. He was made the superior knight of the gods to destroy Prabu Niwatakawaca, the giant king of the Manimantaka country. For his services, Arjuna was crowned king in Dewa Indra's heaven, with the title King Karitin and get the gift of magical heirlooms from the gods, including: Gendewa (from Bhatara Indra), Ardadadali Arrow (from Bhatara Kuwera), Cundamanik Arrow (from Bhatara Narada). After the Bharatayuddha war, Arjuna became king in Banakeling State, the former Jayadrata kingdom.

Arjuna has a smart and clever nature, is quiet, conscientious, polite, brave and likes to protect the weak. He leads the Madukara Duchy, within the territory of the state of Amarta. For the older generation of Java, he was the embodiment of a whole man. Very different from Yudhisthira, he really enjoyed life in the world. His love adventures always amaze the Javanese, but he is different from Don Juan who always chases women. It is said that Arjuna was so refined and handsome that princesses, as well as the ladies-in-waiting, would immediately offer themselves. They are the ones who get the honor, not Arjuna. He is very different from Wrekudara. He displayed a graceful body and a gentleness that was appreciated by the Javanese of all generations.

Arjuna also has other powerful heirlooms, among others: The Kiai Kalanadah Keris was given to Gatotkaca when he married Dewi Gowa (Arjuna's son), Sangkali Arrow (from Resi Drona), Candranila Arrow, Sirsha Arrow, Sarotama Kiai Arrow, Pasupati Arrow (from Batara Guru), Panah Naracabala, Arrow Ardhadhedhali, Keris Kiai Baruna, Keris Pulanggeni (given to Abhimanyu), Terompet Dewanata, Cupu filled with Jayengkaton oil (given by Bagawan Wilawuk from Pringcendani hermitage) and Ciptawilaha Horse with Kiai Pamuk's whip. Arjuna also has clothes that symbolize greatness, namely Kampuh or Limarsawo Cloth, Limarkatanggi Belt, Minangkara Gelung, Candrakanta Necklace and Mustika Ampal Ring (formerly belonging to King Ekalaya, the king of the Paranggelung state).[73][74]

In popular culture

[edit]- The American astronomer Tom Gehrels named a class of asteroids with low inclination, low eccentricity and earth-like orbital period as Arjuna asteroids.[75]

- The Arjuna Award is presented every year in India to one talented sportsperson in every national sport.

- Arjun is a third generation main battle tank developed for the Indian Army.[76]

- Mayilpeeli Thookkam is a ritual art of dance performed in the temples of Kerala. It is also known as Arjuna Nrithyam ('Arjuna's dance') as a tribute to his dancing abilities. [citation needed]

- Arjuna is also an Archer class Servant in the mobile game Fate/Grand Order. He is a minor antagonist in the "E Pluribus Unum" story chapter, where he wishes to fight Karna again.[77] Arjuna also appears as a rogue Archer servant in the game Fate/Samurai Remnant as one of servants recruitable by the protagonist Iori.

- The protagonist in Steven Pressfield's 1995 book The Legend of Bagger Vance and its 2000 film adaptation, Rannulph Junuh, is based in part on Arjuna (R. Junuh).[78]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Despite being the younger brother of Dhritarashtra, it was Pandu who succeeded their father as king of Bharata. This was because Dhritarashtra was blind, a disability that caused him to forfeit his right to the royal succession. Dhritarashtra fathered 100 sons, known as the Kaurava brothers, and ascended the throne after Pandu went on self imposed exile to forest.[17][18]

- ^ The Southern and other vulgate recensions include additional episodes. In one, Drona begins advanced lessons for his son Ashvatthama while sending others to fetch water. Perceiving this, Arjuna returns early with Ashvatthama to receive the same training. Impressed by his insight and dedication, Drona instructs both students in specialised techniques. Another episode recounts that one day, a gust of wind extinguishes the lamp while Arjuna is eating, yet he continues instinctively. Realising that archery, too, can be mastered in darkness, he begins practising at night.[33]

- ^ According to scholar Kevin McGrath, while both Arjuna and Karna are depicted as supreme warriors, the Mahabharata characterises Arjuna as possessing supernatural qualities, whereas Karna, though formidable, remains within the bounds of the merely superhuman.[26]

- ^ In the southern recension, the narrative adopts a more romantic tone: at Krishna’s suggestion, Arjuna disguises himself as an ascetic and stays as a guest in royal palace after the festival, while Subhadra is tasked with caring for him. In this version, Arjuna discovers that Subhadra has long harboured feelings for him, having heard of his deeds. Their affection grows, and Arjuna eventually reveals his identity before the abduction—or elopement in this case.[54]

Citations

- ^ "Arjuna | Mahabharata, Pandava, Warrior | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 14 April 2025. Retrieved 3 June 2025.

- ^ Davis, Richard H. (26 October 2014). The Bhagavad Gita. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13996-8. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Sunil K. (1996). Krishna-cult in Indian art (1. publ ed.). New Delhi: M. D. Publ. ISBN 978-81-7533-001-6.

- ^ Monier-Williams, Monier (1872). A Sanskṛit-English Dictionary Etymologically and Philologically Arranged: With Special Reference to Greek, Latin, Gothic, German, Anglo-Saxon, and Other Cognate Indo-European Languages. Clarendon Press. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ "Arjuna's Many Names". The Hindu. 14 August 2018. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ "Reasons for the names". The Hindu. 8 July 2018. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 1: Adi Parva: Vaivahika Parva: Section CLXLIX". Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 3: Vana Parva: Markandeya-Samasya Parva: Section CCXXX". Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 3: Vana Parva: Tirtha-yatra Parva: Section CLXIV". Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ "Rig Veda: Rig-Veda, Book 7: HYMN XXXV. Viśvedevas". Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ a b "The Mahabharata, Book 4: Virata Parva: Go-harana Parva: Section XLIV". Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ Brockington, J. L. (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. Brill Academic. p. 26. ISBN 978-9-00410-260-6.

- ^ Minor, Robert N. (1982). Bhagavad Gita: An Exegetical Commentary. South Asia Books. pp. l–li. ISBN 978-0-8364-0862-1. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ McGrath, Kevin (2004). The Sanskrit Hero: Karna in Epic Mahabharata. Brill Academic. pp. 19–26. ISBN 978-9-00413-729-5. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ McGrath 2016, p. 22.

- ^ Johnson, W. J. (1 January 2009), "Pandu", A Dictionary of Hinduism, doi:10.1093/ACREF/9780198610250.001.0001, OL 3219675W, Wikidata Q55879169

- ^ a b Narlikar, Amrita; Narlikar, Aruna (2014). Bargaining with a Rising India: Lessons from the Mahabharata. Oxford University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-19161-205-3. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ a b Flood, Gavin; Martin, Charles (2012). The Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-39308-385-9. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ a b Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (4 July 2013). "Arjuna". Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-13596-390-3.

- ^ Johnson, W. J. (1 January 2009), "Pandavas", A Dictionary of Hinduism, doi:10.1093/ACREF/9780198610250.001.0001, OL 3219675W, Wikidata Q55879169

- ^ McGrath 2016, p. 26-27.

- ^ Katz 1990, p. 29-30.

- ^ Brodbeck 2017, p. 183.

- ^ Katz 1990, p. 283.

- ^ Katz 1990, p. 42.

- ^ a b McGrath 2016, p. 29.

- ^ Johnson, W. J. (1 January 2009), "Bisma", A Dictionary of Hinduism, doi:10.1093/ACREF/9780198610250.001.0001, OL 3219675W, Wikidata Q55879169

- ^ a b c Katz 1990, p. 43.

- ^ McGrath 2016, p. 25-26.

- ^ Johnson, W. J. (1 January 2009), "Drona", A Dictionary of Hinduism, doi:10.1093/ACREF/9780198610250.001.0001, OL 3219675W, Wikidata Q55879169

- ^ McGrath 2016, p. 28.

- ^ McGrath 2016, p. 30.

- ^ Mani 2015, p. 49.

- ^ McGrath 2016, p. 28-30.

- ^ a b Katz 1990, p. 45.

- ^ Mani, Vettam (1 January 2015). Puranic Encyclopedia: A Comprehensive Work with Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0597-2. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Katz 1990, p. 46.

- ^ McGrath 2016, p. 33.

- ^ McGrath 2016, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Katz 1990, p. 56-8.

- ^ a b c McGrath 2016, p. 33-35.

- ^ Hiltebeitel, Alf (1991). Mythologies: From Gingee to Kurukṣetra. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. pp. 207–8. ISBN 978-81-208-1000-6.

- ^ Katz 1990, p. 58-59.

- ^ Brodbeck 2017, p. 182.

- ^ Katz 1990, p. 60.

- ^ a b McGrath 2016, p. 36.

- ^ Katz 1990, p. 60-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Katz 1990, p. 62.

- ^ Brodbeck 2017, p. 183-6.

- ^ Katz 1990, p. 69.

- ^ a b c d McGrath 2016, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e Brodbeck 2017, p. 186-7.

- ^ a b Hiltebeitel, Alf (5 July 1990). The Ritual of Battle: Krishna in the Mahabharata. SUNY Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-79140-250-4. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ Mani 2015, p. 746.

- ^ Framarin, Christopher G. (2014). Hinduism and Environmental Ethics: Law, Literature and Philosophy. Routledge. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-1-31791-894-3. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ Johnson, W. J. (1 January 2009), "Yudhisthira", A Dictionary of Hinduism, doi:10.1093/ACREF/9780198610250.001.0001, OL 3219675W, Wikidata Q55879169

- ^ Johnson, W. J. (1 January 2009), "Rajasuya", A Dictionary of Hinduism, doi:10.1093/ACREF/9780198610250.001.0001, OL 3219675W, Wikidata Q55879169

- ^ Williams, George M. (2008). "Arjuna". Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-19533-261-2. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ a b Johnson, W. J. (1 January 2009), "Draupadi", A Dictionary of Hinduism, doi:10.1093/ACREF/9780198610250.001.0001, OL 3219675W, Wikidata Q55879169

- ^ a b Johnson, W. J. (1 January 2009), "Mahabharata", A Dictionary of Hinduism, doi:10.1093/ACREF/9780198610250.001.0001, OL 3219675W, Wikidata Q55879169

- ^ McGrath, Kevin (1 January 2004). The Sanskrit Hero: Karṇa in Epic Mahābhārata. BRILL. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-90-04-13729-5. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ a b Sharma, Arvind; Khanna, Madhu (15 February 2013). Asian Perspectives on the World's Religions after September 11. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37897-3. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Sharma, Mahesh; Chaturvedi, B. K. (2006). Tales From the Mahabharat. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. ISBN 978-81-288-1228-6. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Chandramouli, Anuja (15 December 2012). ARJUNA: Saga Of A Pandava Warrior-Prince. Leadstart Publishing Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-81576-39-7. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Bhanot, T. R. (1990). The Mahabharata. New Delhi: Dreamland Publications. p. 19. ISBN 9788173010453.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 80.

- ^ Davis, Richard H. (2014). The "Bhagavad Gita": A Biography. Princeton University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-69113-996-8.

- ^ Debroy, Bibek (1 September 2012). The Mahabharata: Volume 5 (Volume 5 ed.). India: Penguin Books India. pp. 500–656. ISBN 978-0143100201.

- ^ Barpujari, H. K. (1990). The Comprehensive History of Assam: Ancient period. Publication Board, Assam. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Debroy, Bibek (2015). The Mahabharata: Volume (Volume 7 ed.). Haryana: Penguin Books India (published 1 June 2015). ISBN 978-0143425205.

- ^ Krishna & Human Relations. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. 2001. ISBN 9788172762391. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Bowker, John (2000). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780192800947.001.0001. ISBN 9780192800947.[clarification needed]

- ^ Ensiklopedia tokoh-tokoh wayang dan silsilahnya. Penerbit Narasi. 2010. ISBN 9789791681896. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Enneagram dalam Wayang Purwa. Gramedia Pustaka Utama. 27 May 2013. ISBN 9789792293562. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, C.; de la Fuente Marcos, R. (12 February 2015). "Geometric characterization of the Arjuna orbital domain". Astronomische Nachrichten. 336 (1): 5–22. arXiv:1410.4104. Bibcode:2015AN....336....5D. doi:10.1002/asna.201412133.

- ^ "Arjun Main Battle Tank". Army Technology. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Lynn, David. "Archers in the Fate Universe Who ACTUALLY Use Bows". Crunchyroll. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Rosen, Steven (30 May 2002). Gita on the Green: The Mystical Tradition Behind Bagger Vance – Steven Rosen – Google Boeken. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780826413659. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Katz, Ruth Cecily (1 January 1990). Arjuna in the Mahabharata: Where Krishna Is, There Is Victory. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0744-0.

- McGrath, Kevin (2016). Arjuna Pandava: The Double Hero in Epic Mahabharata. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-8-12506-309-4.

- Brodbeck, Simon Pearse (2 March 2017). The Mahabharata Patriline: Gender, Culture, and the Royal Hereditary. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-88630-7.

- Brodbeck, Simon; Black, Brian (2007). Gender and Narrative in the Mahabharata. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-11994-3.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (28 July 2011). Dharma: Its Early History in Law, Religion, and Narrative. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-987524-5.

- Buitenen, Johannes Adrianus Bernardus (1973). The Mahābhārata. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-84663-7.

- Brockington, J. L. (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. Brill Academic. p. 26. ISBN 978-9-00410-260-6.

- Minor, Robert N. (1982). Bhagavad Gita: An Exegetical Commentary. South Asia Books. pp. l–l1. ISBN 978-0-8364-0862-1. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Doniger, Wendy (March 2014). On Hinduism. OUP USA. ISBN 978-0-19-936007-9.

- McGrath, Kevin (2004). The Sanskrit Hero: Karna in Epic Mahabharata. Brill Academic. pp. 19–26. ISBN 978-9-00413-729-5. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Chakrabarti, Arindam; Bandyopadhyay, Sibaji (2017). Mahabharata Now: Narration, Aesthetics, Ethics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-34213-7.

- Dikshitar, V R Ramachandra (1952). The Purana Index (from T To M) Vol-II.

- Sharma, Arvind (2007). Essays on the Mahābhārata. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-2738-7.

External links

[edit]Arjuna at the Encyclopædia Britannica

Arjuna

View on GrokipediaBackground

Etymology and epithets

The name Arjuna derives from the Sanskrit adjective arjuna, which means "white," "clear," or "shining," as defined in classical lexicons, and is often linked to the character's fair complexion and symbolic purity in epic narratives.[4] This etymology underscores Arjuna's portrayal as a luminous and unblemished hero, reflecting ideals of moral clarity and divine favor in ancient Indian literature.[5] Arjuna bears numerous epithets that encapsulate his lineage, prowess, and attributes, each rooted in specific Sanskrit terms and tied to his exploits. Partha, meaning "son of Pritha" (his mother Kunti's maiden name), highlights his maternal heritage and Pandava identity. Dhananjaya, from dhana (wealth) and jaya (victory), signifies his role as a conqueror of riches, particularly during campaigns like the Rajasuya sacrifice where he subdued kingdoms to amass tributes. Kiriti, derived from kirita (diadem or crown), refers to the celestial crown bestowed upon him by Indra, symbolizing his exalted warrior status and divine endorsements. Shvetavahana, combining shveta (white) and vahana (chariot or horses), denotes his chariot drawn by white horses, a distinctive feature that marked his battlefield presence and agility.[6] Among these, epithets like Gudakesha—from gudaka (sleep or ignorance) and isha (lord or conqueror)—emphasize Arjuna's vigilance and spiritual discipline, portraying him as one who masters drowsiness and delusion through unwavering focus and yogic practice. This title, frequently used in the Bhagavad Gita, ties to his ability to remain alert amid trials, reinforcing themes of self-control and enlightenment in his character arc. Such descriptors collectively illustrate how Arjuna's names function as multifaceted symbols, blending personal traits with narrative achievements to deepen his heroic archetype.[6][7]Literary background

Arjuna is primarily depicted in the ancient Indian epic Mahabharata as the third of the five Pandava brothers, renowned for his unparalleled archery skills and as the intimate companion of Krishna, who serves as his charioteer and philosophical guide during the Kurukshetra war.[8] This portrayal establishes Arjuna as a central heroic figure whose exploits drive much of the narrative, emphasizing themes of duty, valor, and divine intervention. In the Harivamsa, an appendix to the Mahabharata, Arjuna's role expands through his connections to Krishna's divine lineage, portraying him as part of the broader cosmic drama involving the Yadavas and Pandavas. Similarly, the Bhagavata Purana references Arjuna within the context of the Pandavas' lineage from the lunar dynasty, highlighting his involvement in key events tied to Krishna's earthly manifestations.[9] In Puranic literature, such as the Vishnu Purana, Arjuna is explicitly identified as the human incarnation of Nara, the eternal ascetic companion of Narayana (Vishnu's form as Krishna), underscoring their inseparable bond as predestined allies in upholding dharma. This divine linkage elevates Arjuna beyond a mere warrior, positioning him as a partial avatar in the cosmic order. The Mahabharata's critical edition reveals Arjuna's character development from a formidable warrior driven by prowess and ambition to a reflective devotee seeking spiritual wisdom, particularly through his existential crisis on the battlefield resolved by Krishna's teachings in the Bhagavad Gita. This evolution reflects an integration of martial excellence with ethical introspection, where Arjuna grapples with moral dilemmas, transitioning from doubt and inaction to resolute devotion.[8] Scholars note that certain passages enhancing this philosophical arc, such as expanded dialogues on devotion, may stem from later interpolations added during the epic's textual growth, as identified in the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute's edition. Epithets like Phalguna serve as narrative devices to invoke these multifaceted traits, reinforcing his heroic yet humble persona.[10] Composed over centuries from circa 400 BCE to 400 CE, the Mahabharata and associated texts like the Harivamsa originated in oral bardic traditions, allowing Arjuna's persona to evolve through regional retellings that blended heroic lore with emerging Vaishnava theology. This multifaceted portrayal, influenced by pre-existing Vedic motifs of divine companionship, transformed Arjuna into a philosophical archetype embodying the tension between action and surrender.[11]Early Life

Birth and early life

Arjuna was conceived through the invocation of the storm god Indra by his mother Kunti, utilizing a divine boon granted to her by the sage Durvasa, as her husband King Pandu was unable to sire children due to a curse from sage Kindama.[12] This made Arjuna the divine son of Indra and the third Pandava brother, following Yudhishthira (son of Dharma) and Bhima (son of Vayu).[1] Born in a secluded forest hermitage on the slopes of the Satasringa mountain, his arrival was marked by celestial portents, including the sounds of divine music and a heavenly voice proclaiming his future prowess as a warrior unmatched in battle and capable of performing the Ashvamedha sacrifice.[12] Kunti named him Arjuna, meaning "bright" or "shining," reflecting his radiant complexion and innate vigor from birth.[13] Following the death of Pandu and Madri—Kunti's co-wife and mother to the twins Nakula and Sahadeva—the young Pandavas, including the infant Arjuna, were brought from the forest to the royal palace in Hastinapura by Kunti, under the protection of their grandfather Bhishma and uncle Dhritarashtra.[12] There, amid the Kuru dynasty's growing internal rivalries between the Pandavas and their hundred step-cousins, the Kauravas sired by Dhritarashtra and Gandhari, Arjuna grew up in a harmonious bond with his four brothers, sharing in their upbringing under Kunti's vigilant care.[1] The family dynamics were tense from the outset, as the Kauravas, led by the envious Duryodhana, viewed the Pandavas' exceptional qualities with jealousy, fostering an atmosphere of subtle antagonism within the palace.[12] Madri's absence after her sati left Kunti as the primary maternal figure, guiding the brothers through these early years marked by the dynasty's power struggles. In his early childhood, Arjuna displayed initial signs of extraordinary talent, particularly an innate aptitude for archery that set him apart even before formal instruction, often playing with toy bows alongside his brothers in the palace gardens.[12] The Pandavas' survival was threatened early on by Kaurava schemes, including an attempt to poison Bhima during a river outing, where Duryodhana administered a potent toxin in his food; Bhima not only survived by digesting the poison but gained enhanced strength after being revived by Naga serpents in the Ganges.[12] This incident underscored the perilous environment of their upbringing, yet the brothers remained united, their close sibling ties providing resilience against the Kuru court's intrigues. Arjuna's divine parentage from Indra later influenced boons such as access to celestial weapons.[1]Education and training

Arjuna's formal education in martial arts began under the tutelage of Kripacharya in Hastinapura, where the Pandava and Kaurava princes received instruction in archery, swordsmanship, and chariot warfare. Kripacharya, a skilled warrior of divine origin, emphasized discipline and basic combat techniques, and Arjuna quickly distinguished himself through his natural aptitude and dedication, surpassing many of his peers in precision and agility. Following this foundational training, Arjuna apprenticed under Drona, the renowned Brahmin warrior invited by Bhishma to elevate the princes' skills. Drona provided advanced lessons in celestial and earthly weapons, including mounted combat, multi-weapon handling, and strategies for engaging multiple foes.[14] A defining moment came during a test of focus, where Drona suspended a wooden bird from a tree and instructed his pupils to aim at its eye while describing what they saw; Arjuna alone perceived only the target, declaring, "I see the bird, and only the bird," before striking it flawlessly with an arrow.[15] This feat earned him Drona's highest regard, establishing him as the preceptor's favorite disciple and affirming his unparalleled concentration.[16] Under Drona's guidance, Arjuna acquired potent divine astras, such as the Brahmastra, a weapon of immense destructive power invoked through sacred mantras. Drona imparted the knowledge of its invocation and retraction exclusively to Arjuna, along with strict ethical directives: it was not to be used against ordinary humans or inferior warriors, as its misuse could devastate the world, and Arjuna vowed to wield it responsibly.[15] These teachings underscored the balance between martial prowess and moral restraint.[17] During the grand tournament showcasing the princes' skills, Arjuna's rivalry with Karna emerged prominently, foreshadowing their lifelong enmity. As Arjuna demonstrated extraordinary feats with divine weapons, Karna, a skilled outsider, interrupted to match him arrow for arrow, challenging Arjuna to a duel that highlighted their equal prowess but was halted by protocol, igniting tensions among the assembly.[18] This confrontation during training intensified Karna's resentment toward Arjuna, rooted in perceived favoritism and social barriers.Youth and early adventures

Following the completion of his training under Drona, Arjuna participated in a grand tournament organized by his guru in Hastinapura to demonstrate the martial prowess of the Kuru princes.[19] The event, held on an auspicious day in a specially prepared arena adorned with gold and jewels, drew King Dhritarashtra, Bhishma, Kripa, and crowds of citizens. Arjuna, as the preeminent archer among the Pandavas, showcased unparalleled skills in wielding various weapons, including feats of archery that left spectators in awe, with exclamations of admiration echoing through the assembly.[19] His demonstrations highlighted his superiority over his peers, including the Kauravas, establishing his reputation as an exceptional warrior from a young age.[19] During the tournament, Karna, a skilled archer of unknown royal lineage who had trained under Parashurama, entered the arena and directly challenged Arjuna to a duel after the latter's display.[20] Eager to prove himself, Karna matched Arjuna's feats with equal dexterity, creating a tense rivalry that captivated the onlookers.[20] However, Kripa intervened, stipulating that Karna must declare his lineage and bring a suitable challenger, as only equals could compete, which temporarily halted the confrontation and underscored the protocols of Kshatriya combat.[20] This encounter marked the beginning of a lifelong antagonism between Arjuna and Karna, while affirming Arjuna's preeminence among the youth.[20] In these early years, Arjuna also began forging key familial bonds that would shape his future alliances, notably with his cousin Krishna, son of Vasudeva and thus related through Arjuna's mother Kunti, who was Vasudeva's sister. As cousins from the Yadava and Kuru lineages, their relationship provided Arjuna with an early foundation of support and mutual respect, laying the groundwork for Krishna's role as a trusted advisor and ally. These connections, combined with his protective instincts toward his mother Kunti and brothers during their subsequent trials, demonstrated Arjuna's emerging leadership and commitment to family honor.Marriages and Family

Svayamvara and marriage to Draupadi

The swayamvara of Draupadi, the princess of Panchala, was organized by her father, King Drupada, in an elaborate amphitheatre near his capital to select a suitable husband from among the assembled kings and princes.[21] Draupadi, also known as Krishnaa or Yajnaseni, had been born miraculously from the sacrificial fire during one of Drupada's yajnas, emerging fully formed without a human mother, symbolizing her divine origin and exceptional status.[22] The contest required participants to string a exceptionally stiff bow and then shoot arrows to hit a specific mark suspended above, a task designed to test superior archery skills.[23] The Pandava brothers, living incognito after their escape from the lac house, attended the event disguised as Brahmins, with Arjuna particularly drawn to the challenge due to his renowned prowess in archery honed from youth.[23] Numerous suitors, including prominent warriors like Karna and Duryodhana, attempted the feat but failed; Karna successfully strung the bow but was publicly rejected by Draupadi, who declared she would not marry the son of a charioteer, prompting him to withdraw.[23] Arjuna, rising from among the Brahmins, effortlessly strung the bow and accurately struck the target with five arrows, securing victory amid astonishment from the assembly and winning Draupadi's hand.[23] When his identity as a Kshatriya was revealed through the ensuing chaos and inquiries by Drupada's court, the king accepted the match, having long desired an alliance with the Pandavas, though initially wary of the disguise.[24] Upon returning to their abode with Draupadi, the brothers announced their success to their mother Kunti, who, without turning to see, habitually instructed them from her routine of alms-sharing: "Whatever it may be, share it equally among yourselves, as per dharma." Realizing the import— that the "alms" was the bride Draupadi—Kunti was distraught, but the brothers, bound by filial obedience and the irrevocability of her word, resolved to uphold the polyandrous marriage, with Draupadi becoming the common wife of all five Pandavas, starting with the eldest Yudhishthira. This unusual arrangement, justified by Vyasa's counsel as fulfilling a divine prophecy linking Draupadi to the five Indras, established the controversial practice of polyandry within the family. Following the wedding ceremonies, the Pandavas relocated to Indraprastha, where they established their capital with Draupadi as the chief empress, overseeing the household and embodying the prosperity of their emerging kingdom. Her fire-born purity and grace elevated her role, fostering unity among the brothers during their initial years of governance and expansion.[22]Pilgrimage and encounters

During the Pandavas' forest exile, Arjuna undertook a self-imposed journey of atonement after inadvertently violating a fraternal vow by entering a chamber where Yudhishthira and Draupadi were together, necessitated by the need to retrieve his weapons to aid a distressed Brahmana. This incident, occurring amid their collective banishment, prompted Arjuna to embark on a dedicated pilgrimage lasting approximately one year, aimed at acquiring celestial weapons essential for upholding dharma in the impending conflict. Directed by Yudhishthira, Arjuna departed from the Kamyaka forest, vowing rigorous austerities to seek boons from the gods, thereby reinforcing his commitment to kshatriya duties of protection and righteousness.[25][26] Arjuna's pilgrimage took him to sacred sites, including the northern extremities of the Himalayas, where he engaged in intense penances amid encounters with revered sages. Clad in bark garments and surviving on sparse sustenance—such as fruit every three days initially, progressing to air alone—he stood on tiptoes with arms raised for months, his body emaciated yet resolute. These interactions with rishis, who observed his devotion shaking the earth, underscored his spiritual discipline and deepened his understanding of isolation as a path to inner strength and moral clarity. The sages' guidance highlighted the warrior's code, emphasizing self-control and devotion as prerequisites for divine favor.[27] A pivotal encounter occurred when Arjuna, in deep meditation on Mount Himavat, faced a disguised Shiva in the form of a hunter (Kirata) during a hunt for a demonic boar. Mistaking the god for a rival, Arjuna engaged in a fierce battle, unleashing arrows and celestial missiles that proved ineffective against the hunter's invulnerability. Overpowered in hand-to-hand combat, Arjuna prostrated himself, invoking worship; Shiva then revealed his true form as Mahadeva, pleased by Arjuna's valor and tapasya. Granting the invincible Pashupatastra—a weapon capable of unparalleled destruction—Shiva instructed its ethical use, only in dire necessity to preserve cosmic balance, thereby imparting lessons on dharma's restraint amid martial prowess.[28][29] Following this boon, Arjuna continued to Indra's celestial realm, transported by the charioteer Matali in a divine vehicle adorned with thunderbolts and serpents. There, he received further astras from Indra, Varuna, Yama, and Kubera, including divine armor and illusions, after demonstrations of humility and further austerities. Indra, as Arjuna's divine father, revealed visions of the cosmic order, showcasing heavenly assemblies, virtuous souls, and the interplay of fate and action. These experiences prompted Arjuna's profound reflections on dharma, contemplating the warrior's role in maintaining universal harmony through selfless duty, free from attachment to outcomes, and the isolation of the path as a forge for ethical resolve.[30][26]Additional marriages

During his exile, Arjuna's pilgrimage along the sacred rivers led to his encounter with Ulupi, daughter of the Naga king Kauravya, while he bathed in the Ganges. Overcome by passion, Ulupi drew the reluctant warrior into her underwater palace and implored him to unite with her, citing her distress and his duty to protect a supplicant despite his vow of celibacy toward Draupadi. Arjuna acquiesced, and they spent the night together; Ulupi then granted him a boon ensuring invincibility against all aquatic creatures in battle. Their union produced a son, Iravan (also called Iravat), who was raised among the Nagas and later joined the Pandavas in the Kurukshetra War. This marriage cemented an alliance between the Pandavas and the powerful Naga realms, providing supernatural support.[31][32] Proceeding southward to the kingdom of Manipur, Arjuna arrived at the court of King Chitravahana and became enamored with his daughter, the princess Chitrangada, renowned for her beauty and grace. Seeking her hand, Arjuna received the king's consent under a strict condition dictated by a divine boon from Shiva: any son born to them would remain in Manipur to perpetuate Chitravahana's lineage, as he was fated to have only one male heir. Arjuna agreed, married Chitrangada, and resided with her for three years, during which she bore a son named Babhruvahana, who was groomed as the future ruler of Manipur. This union forged a vital political tie with the eastern kingdom, enhancing the Pandavas' regional influence.[33] Arjuna's travels eventually brought him to Dwaraka, where he took refuge incognito in Krishna's temple. At a grand festival on Raivataka Hill, he glimpsed Subhadra, Krishna's cherished sister, and was instantly captivated by her poise and charm. Consulting Krishna, who approved and devised a plan, Arjuna— with Yudhishthira's blessing—abducted Subhadra in a rakshasa-style marriage traditional for Kshatriya warriors, as she willingly mounted his chariot. Though the Yadavas pursued in outrage, Krishna intervened to affirm the union. Returning to Indraprastha, Subhadra gave birth to Abhimanyu, a prodigious warrior trained in arms by Arjuna and Krishna. Celebrated as a love match orchestrated by divine kinship, this marriage profoundly strengthened the Pandava-Yadava alliance, uniting two formidable clans against common foes.[34][35] These additional marriages not only expanded Arjuna's lineage but also wove strategic webs of kinship: with the Nagas for mystical aid, Manipur for territorial leverage, and the Yadavas for military prowess, all pivotal to the Pandavas' eventual triumph.Pre-War Events

Burning of Khandava Forest

The Burning of Khandava Forest episode marks a pivotal alliance between Arjuna and Krishna, undertaken at the behest of Agni, the god of fire, who sought to cure his indigestion caused by excessive consumption of sacrificial offerings.[36] Disguised as a Brahmana, Agni approached the two warriors while they rested by the Yamuna River near Indraprastha, requesting their aid to burn the demon-infested Khandava forest, which he intended to devour as remedy.[36] The forest, a vast woodland teeming with nagas, asuras, and other creatures, had long been protected by Indra, the king of gods, due to his friendship with the naga Takshaka who resided there.[36] Arjuna, drawing on his prior training in celestial weaponry under gurus like Drona, agreed to assist but stipulated the need for superior arms to counter Indra's inevitable intervention.[37] Agni, pleased with their resolve, summoned Varuna, the god of water, who bestowed upon Arjuna the invincible Gandiva bow—crafted by Brahma, passed through Vishnu and Soma, and capable of summoning divine astras—along with two inexhaustible quivers of arrows.[38] Indra, though initially opposed, later granted Arjuna a celestial chariot yoked to white horses of divine speed, adorned with a banner bearing the image of Hanuman, ensuring its indestructibility in battle.[38] With these divine endowments, Arjuna and Krishna positioned themselves on opposite sides of the forest; Agni then entered Khandava in a blazing form, igniting the trees and consuming the woodland in a purifying inferno meant to eradicate the demonic inhabitants.[39] The fire raged for fifteen days, its flames reaching the heavens and filling the air with smoke, heat, and the cries of fleeing creatures including birds, beasts, and aquatic life in boiling ponds.[40] Indra, enraged by the destruction of his protected domain, summoned massive clouds to unleash torrential rains, aiming to quench the blaze and rescue the survivors.[39] However, Arjuna countered this by unleashing a barrage of arrows that formed an impenetrable canopy, evaporating the downpour through Agni's intensifying heat, while Krishna wielded his Sudarshana discus to repel the godly forces dispatched by Indra, including the wind god and other devas.[39] This fierce confrontation turned the burning into a cosmic battle, with Arjuna's Gandiva resounding like thunder as he slew thousands of escaping denizens—birds pierced mid-flight, serpents charred, and asuras vanquished—ensuring Agni's feast proceeded unhindered.[39] The ethical tensions arose as not all inhabitants perished; Arjuna spared the asura architect Maya, who sought refuge in the waters, at Krishna's urging, recognizing his potential utility.[40] Further dilemmas emerged with the naga Ashvasena, son of Takshaka, who hid within his mother's burning body to escape; Arjuna severed her head with an arrow, but Indra's whirlwind aided Ashvasena's flight to safety, an act that Arjuna, Krishna, and Agni later cursed for its deceit.[41] Takshaka himself evaded the fire, having been absent in the Himalayas, though the forest's purge was partly aimed at his kin.[41] Four young sarngaka birds also attempted escape with their eggs, but only one succeeded after the others' heroic but fatal efforts to shield their young from the flames.[40] These mercies amid widespread annihilation foreshadowed lingering enmities, particularly with the nagas. Upon the forest's complete consumption, Agni was cured and departed in satisfaction, leaving the scorched expanse cleared for habitation.[41] In gratitude, Maya, the spared asura, offered his services to the Pandavas and constructed the magnificent assembly hall and palace of Indraprastha, transforming the site into their flourishing capital and symbol of prosperity.[40] This event not only armed Arjuna with tools central to his future exploits but also solidified the Pandavas' territorial foundation, blending destruction with renewal.[42]The game of dice