Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

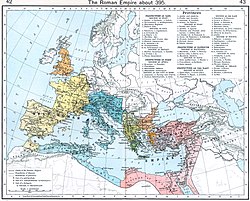

Theodosian dynasty

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

The Theodosian dynasty was a Roman imperial family that produced five Roman emperors during Late Antiquity, reigning over the Roman Empire from 379 to 457. The dynasty's patriarch was Theodosius the Elder, whose son Theodosius the Great was made Roman emperor in 379. Theodosius's two sons both became emperors, while his daughter married Constantius III, producing a daughter that became an empress and a son also became emperor. The dynasty of Theodosius married into, and reigned concurrently with, the ruling Valentinianic dynasty (r. 364–455), and was succeeded by the Leonid dynasty (r. 457–518) with the accession of Leo the Great.

History

[edit]Its founding father was Flavius Theodosius (often referred to as Count Theodosius), a great hispanic general who had saved Britannia from the Great Conspiracy. The future usurper and Western emperor, Magnus Maximus (r. 383–388), was born in his estates, and claimed to be his relative. However, this may not be true. His son, Flavius Theodosius was made emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire in 379, and briefly reunited the Roman Empire 394–395 by defeating the usurper Eugenius. Theodosius I was succeeded by his sons Honorius in the West and Arcadius in the East. The House of Theodosius was related to the Valentinianic Dynasty by marriage, since Theodosius I had married Galla, a daughter of Valentinian I. Their daughter was Galla Placidia. The last emperor in the West belonging to the dynasty was Galla Placidia's son Valentinian III. The last emperor of the dynasty in the East was Theodosius II, the son of Arcadius. Later, both in the East and in the West, the dynasty briefly continued, but only through marriages: Marcian became emperor by marrying Pulcheria, the older sister of Theodosius II, after the death of the latter, Petronius Maximus was married to Licinia Eudoxia, the daughter of Theodosius II, and Olybrius was married to Placidia, the daughter of Valentinian III. Anthemius is also sometimes counted to the dynasty as he became a son-in-law of Marcian. Descendants of the dynasty continued to be part of the East Roman nobility at Constantinople until the end of the 6th century.

According to Polemius Silvius, Theodosius the Great was born on 11 January 347 or 346.[1] The epitome de Caesaribus places his birthplace at Cauca (Coca, Segovia) in Hispania.[1] Theodosius had a brother named Honorius, a sister referred to in Aurelius Victor's De caesaribus but whose name is unknown, and a niece, Serena.[1]

In 366, Theodosius the Elder attacked and defeated the Alamanni in Gaul; the defeated prisoners were resettled in the Po Valley.[2][3] In 367 Roman Britain was threatened by the Great Conspiracy, defeated 368–369 by the magister equitum Theodosius the Elder, accompanied by his son Theodosius.[2][3][1] At this time was the unsuccessful usurpation in Britain by Valentinus.[3] Theodosius the Elder was made magister equitum in 369, and retained the post until 375.[1] The magister equitum and his son Theodosius campaigned against the Alamanni 370.[1] The two Theodosi campaigned against Sarmatians in 372/373.[1] Valentinian's rule in Roman Africa was disrupted by the revolt of Firmus in 373.[2] Theodosius the Elder defeated the usurpation.[2]

In 373/374, Theodosius the magister equitum's son, was made dux of the province of Moesia Prima.[1] At the fall of his father, Theodosius the dux of Moesia Prima retired to his estates in the Iberian Peninsula, where he married Aelia Flaccilla in 376.[1] Their first child, Arcadius, was born around 377.[1] Pulcheria, their daughter, was born in 377 or 378.[1] Theodosius had returned to the Danube frontier by 378, when he was appointed magister equitum.[1]

First generation emperor: Theodosius the Great

[edit]

After the death of his uncle Valens (r. 364–378), Gratian, now the senior augustus, sought a candidate to nominate as Valens's successor. On 19 January 379, Theodosius I was made augustus over the eastern provinces at Sirmium.[1][4] His wife, Aelia Flaccilla, was accordingly raised to augusta.[1] The new augustus's territory spanned the Roman praetorian prefecture of the East, including the Roman diocese of Thrace, and the additional dioceses of Dacia and of Macedonia. Theodosius the Elder, who had died in 375, was then deified as: Divus Theodosius Pater, lit. 'the Divine Father Theodosius'.[1] In October 379 the Council of Antioch was convened.[1] On 27 February 380 Theodosius issued the Edict of Thessalonica, making Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire.[1] In 380, Theodosius was made Roman consul for the first time and Gratian for the fifth; in September the augusti Gratian and Theodosius met, returning the Roman diocese of Dacia to Gratian's control and that of Macedonia to Valentinian II.[4][1] In autumn Theodosius fell ill, and was baptized.[1] According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Theodosius arrived at Constantinople and staged an adventus, a ritual entry to the capital, on 24 November 380.[1]

Theodosius issued a decree against Christians deemed heretics on 10 January 381.[1] According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, on the 11 January, Athanaric, king of the Gothic Thervingi arrived in Constantinople; he died and was buried in Constantinople on 25 January.[1] On 8 May 381, Theodosius issued an edict against Manichaeism.[1] In mid-May, Theodosius convened the First Council of Constantinople, the second ecumenical council after Constantine's First Council of Nicaea in 325; the Constantinopolitan council ended on 9 July.[1] According to Zosimus, Theodosius won a victory over the Carpi and the Sciri in summer 381.[1] On 21 December, Theodosius decreed the prohibition of sacrifices with the intent of divining the future.[1] On 21 February 382, the body of Theodosius's father in law Valentinian the Great was finally laid to rest in the Church of the Holy Apostles.[1] Another Council of Constantinople was held in summer 382.[1] According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, a treaty of foedus was reached with the Goths, and they were settled between the Danube and the Balkan Mountains.[1]

According to the Chronicon Paschale, Theodosius celebrated his quinquennalia on 19 January at Constantinople; on this occasion he raised his eldest son Arcadius to co-augustus.[1] Early 383 saw the acclamation of Magnus Maximus as augustus in Britain and the appointment of Themistius as praefectus urbi in Constantinople.[1] On 25 July, Theodosius issued a new edict against gatherings of Christians deemed heretics.[1] Sometime in 383, Gratian's wife Constantia died.[4] Gratian remarried, wedding Laeta, whose father was a consularis of Roman Syria.[5] On the 25 August 383, according to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Gratian was killed at Lugdunum (Lyon) by Andragathius, the magister equitum of the rebel augustus during the rebellion of Magnus Maximus (r. 383–388).[4] Constantia's body arrived in Constantinople on 12 September that year and was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles on 1 December.[4] Gratian was deified as Latin: Divus Gratianus, lit. 'the Divine Gratian'.[4]

On 21 January 384 all those deemed heretics were expelled from Constantinople.[1] According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Theodosius received in Constantinople an embassy from the Sasanian Empire in 384.[1] In summer 384, Theodosius met his co-augustus Valentinian II in northern Italy.[6][1] Theodosius brokered a peace agreement between Valentinian and Magnus Maximus which endured for several years.[7]

Theodosius's second son Honorius was born on 9 December 384 and titled nobilissimus puer (or nobilissimus iuvenis).[1] Sometime before 386 died Aelia Flaccilla, Theodosius's first wife and the mother of Arcadius, Honorius, and Pulcheria.[1] She died at Scotumis in Thrace and was buried at Constantinople, her funeral oration delivered by Gregory of Nyssa.[1][8] A statue of her was dedicated in the Byzantine Senate.[8] In 384 or 385, Theodosius's niece Serena was married to the magister militum, Stilicho.[1] On 25 May 385, Theodosius reiterated the ban on sacrifices with questions concerning the future with new legislation.[1] In the beginning of 386, Theodosius's first wife Aelia Flaccilla and his daughter Pulcheria both died.[1] That summer the Goths were defeated, together with their settlement in Phrygia.[1] According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, a Roman triumph over the Gothic Greuthungi was then celebrated at Constantinople.[1] The same year, work began on the great triumphal column in the Forum of Theodosius in Constantinople, the Column of Theodosius.[1] On 19 January 387, according to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Arcadius celebrated his quinquennalia in Constantinople.[1] By the end of the month, there was an uprising or riot in Antioch, known as Riot of the Statues.[1] Also in 387, Armenia was divided between Rome and Persia by the peace treaty known as Peace of Acilisene.[1]

The peace with Magnus Maximus was broken in 387, and Valentinian escaped the west with Justina, reaching Thessalonica (Thessaloniki) in summer or autumn 387 and appealing to Theodosius for aid; Valentinian II's sister Galla was then married to the eastern augustus at Thessalonica in late autumn.[6][1] Theodosius may still have been in Thessalonica when he celebrated his decennalia on 19 January 388.[1] Theodosius was consul for the second time in 388.[1] Galla and Theodosius's first child, a son named Gratian, was born in 388 or 389.[1]

On 10 March 388, Christians deemed heretics were forbidden from residing in cities.[1] On 14 March, Theodosius banned the intermarriage of Jews and Christians.[1] In summer 388, Theodosius recovered Italy from Magnus Maximus for Valentinian, and in June, the meeting of Christians deemed heretics was banned by Valentinian.[6][1] Around July, Magnus Maximus was defeated by Theodosius at Siscia (Sisak) and at Poetovio (Ptuj), and on 28 August, Magnus Maximus was executed by Theodosius.[1] According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Arbogast killed Flavius Victor (r. 384–388), Magnus Maximus's young son and co-augustus, in Gaul in August/September that year. Damnatio memoriae was pronounced against them, and inscriptions naming them were erased.[1]

Theodosius came into conflict with Ambrose, bishop of Mediolanum, in October 388 over the persecution of Jews at Callincium-on-the-Euphrates (Raqqa).[1] As mentioned in the Panegyrici Latini and in a panegyric of Claudian's on the sixth consulship of Honorius, Theodosius then received another embassy from the Persians in 389.[1] According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Theodosius staged an adventus on entering Rome on 13 June 389.[1] On 17 June, he issued a decree against Manichaeism.[1] Theodosius had left Valentinian under the protection of the magister militum Arbogast, who then defeated the Franks in 389.[7][6]

In spring 390, possibly in April, the Massacre of Thessalonica was perpetrated by Theodosius's army, leading to a confrontation with Ambrose.[1] Ambrose demanded that the emperor do penance for the massacre.[1] According to the 5th-century church historian Theodoret, on 25 December 390 (Christmas), Ambrose received Theodosius back into the Christian Church in his bishopric of Mediolanum.[1] According to the Chronicon Paschale, on 18 February 391, the head of John the Baptist was translated to Constantinople.[1] On the 24 February, attendance at pagan sacrifices and temples was forbidden by law.[1] In early summer 391, an uprising in Alexandria was suppressed, and the Serapeum of Alexandria was destroyed.[1] On 16 June, pagan worship was prohibited by law.[1] In 391, a delegation from the Roman Senate was snubbed in Gaul because of the reappearance of the Altar of Victory in the Curia Julia.[6]

According to Zosimus, Theodosius then campaigned against marauding barbarian bandits in Macedonia in autumn 391.[1] Eventually, he came to Constantinople, where according to Socrates Scholasticus's Historia Ecclesiastica he held an adventus, entering the city on 10 November 391.[1]

On 15 May 392, Valentinian II died at Vienna in Gaul (Vienne), either by suicide or as part of a plot by Arbogast.[6] He was deified with the consecratio: Divae Memoriae Valentinianus, lit. 'the Divine Memory of Valentinian'.[6] Theodosius was then sole adult emperor, reigning with his son Arcadius. On 22 August at the behest of the magister militum Arbogast, a magister scrinii and vir clarissimus, Eugenius, was acclaimed augustus at Lugdunum (Lyon).[1] On 8 November 392, all cult worship of the gods was forbidden by Theodosius.[1]

According to Polemius Silvius, Theodosius raised his second son Honorius to augustus on 23 January 393.[1] 393 was the year of Theodosius's third consulship.[1] On 29 September 393, Theodosius issued a decree for the protection of Jews.[1] According to Zosimus, at the end of April 394, Theodosius's wife Galla died.[1] On 1 August, a colossal statue of Theodosius was dedicated in Constantinople's Forum of Theodosius, an event recorded in the Chronicon Paschale.[1] According to Socrates Scholasticus, Theodosius defeated Eugenius at the Battle of the Frigidus on 6 September 394 and on 8 September, Arbogast killed himself.[1] According to Socrates, on 1 January 395, Honorius arrived in Mediolanum and a victory celebration was held there.[1]

According to the Consularia Constantinopolitana, Theodosius died in Mediolanum on 17 January 395.[1] His funeral was held there on 25 February, and his body transferred to Constantinople, where according to the Chronicon Paschale he was buried on 8 November 395 in the Church of the Holy Apostles.[1] He was deified as: Divus Theodosius, lit. 'the Divine Theodosius'.[1]

-

Solidi of Hoxne Hoard[c]

Second generation emperors: Arcadius and Honorius

[edit]The two surviving sons of Theodosius ruled the eastern and western halves of the empire after their father died.[1] Theodosius's second wife Galla, the daughter of Valentinian the Great by his second wife Justina, was Galla Placidia, born in 392 or 393.[1] Galla Placidia's brother Gratian, the son of Galla and Theodosius, died in 394.[1] Another son, John (Latin: Ioannes), may have been born in 394.[1] Galla Placidia married Athaulf, the King of the Visigoths in 414; he soon died and she married the patricius Constantius (later Constantius III) in 417.[1] Their children were Justa Grata Honoria and Valentinian III.[9] Constantius III was elevated to augustus in 421 by Honorius, who had no issue, and Galla Placidia was made augusta; Constantius died the same year and Galla Placidia fled to Constantinople.[9]

Third generation emperors: Theodosius II and Valentinian III

[edit]When Honorius died in 423, the primicerius notariorum Joannes (r. 423–425) succeeded as augustus in the west; thereafter Theodosius II (r. 402–450) – son and successor of Arcadius as augustus in the east – moved to install Galla Placidia's son Valentinian as emperor in the west instead, appointing him caesar on 23 October 424.[9] After the fall of Joannes, Valentinian III was made augustus on the first anniversary of his investiture as caesar; he ruled the western provinces until his death on the 16 March 455, though Galla Placidia was regent during his youth. Galla Placidia died on 25 November 450.[1]

-

Solidus of Valentinian II with Theodosius I on the reverse, each holding a mappa

-

Solidus of Galla Placidia[h]

-

Solidus of Valentinian III celebrating an imperial marriage[i]

Imperial members

[edit]In italics are members of the Valentinianic dynasty, descended from Theodosius I's second marriage to Galla, daughter of Valentinian the Great (r. 364–375).

- Theodosius I (379–395)

- Arcadius (r. 383–408)

- Magnus Maximus (r. 383-388, possible relative)

- Honorius (r. 393–423)

- Constantius III (421) through marriage to Galla Placidia

- Galla Placidia (r. 424–450)

- Pulcheria (r. 414–453)

- Theodosius II (r. 402–450)

- Valentinian III (r. 425–455)

- Petronius Maximus (455) through marriage to Licinia Eudoxia

- Marcian (r. 450–457) through marriage to Pulcheria

- Olybrius (472) through marriage to Placidia

Sometimes also counted

- Anthemius (r. 467–472) through marriage to Marcia Euphemia

Stemmata

[edit]In italics the Augusti and the Augustae.

- Sextus Iulius Caesar (Ancestor)

- Marcus Actius

- Iulius Honorius married Flavia Actia / Iulius Theodosius / Iulius Eucherius

- Count Theodosius, married Flavia Thermantia and had issue:

- Theodosius I, married firstly Aelia Flacilla and secondly Galla:

- From marriage between Theodosius I and Aelia Flaccilla:

- Arcadius, married Aelia Eudoxia and had issue:

- Theodosius II, married Aelia Eudocia and had issue:

- Licinia Eudoxia, married firstly Valentinian III (cousin of her father) and secondly Petronius Maximus.

- Flaccilla.

- Arcadius (possibly).

- Flaccilla.

- Pulcheria. Married Marcian.

- The marriage of Pulcheria and Marcian was childless. However it brought into the dynasty a daughter of Marcian from a previous marriage.

- Marcia Euphemia. Married Anthemius.

- From marriage between Marcia Euphemia and Anthemius:

- Anthemiolus.

- Marcianus. Usurper emperor. Married Leontia, a daughter of Leo I and Verina.

- Procopius Anthemius.

- Romulus.

- Alypia. Married Ricimer.

- Arcadia.

- Marina.

- Theodosius II, married Aelia Eudocia and had issue:

- Honorius. Married first Maria and secondly Thermantia. They were sisters, daughters of Stilicho and Serena. From marriage of Honorius and Maria:

- Didymus

- Lagodius

- Theodiosolus

- Verenarius

- Thermantia

- Serena

- Pulcheria.

- Arcadius, married Aelia Eudoxia and had issue:

- From marriage between Theodosius I and Galla, d daughter of Valentinian I and Justina:

- Gratianus.

- Johannes.

- Galla Placidia. Married first Ataulf and secondly Constantius III.

- From marriage between Galla Placidia and Ataulf:

- Theodosius.

- From marriage between Galla Placidia and Constantius III:

- Justa Grata Honoria. Granted the title Augusta. Proposed marriage to Attila the Hun, treaty never concluded. Married Flavius Bassus Herculanus.

- Valentinian III, married Licinia Eudoxia (daughter of his cousin) and had issue:

- Eudocia, married first Palladius, son of Petronius Maximus, and secondly Huneric. From marriage of Eudocia and Huneric king of Vandals:

- Hilderic king of Vandals in North Africa.

- Placidia, married Olybrius and had issue:

- Anicia Juliana, married Areobindus and had issue:

- Olybrius, married Irene, a niece of Anastasius I and had issue:

- Proba. Married Anicius Probus Iunior and had issue:

- Juliana, married Anastasius and had issue:

- Areobindus.

- Placidia.

- Proba.

- Juliana, married Anastasius and had issue:

- Proba. Married Anicius Probus Iunior and had issue:

- Olybrius, married Irene, a niece of Anastasius I and had issue:

- Anicia Juliana, married Areobindus and had issue:

- Eudocia, married first Palladius, son of Petronius Maximus, and secondly Huneric. From marriage of Eudocia and Huneric king of Vandals:

Family tree

[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Notes:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Culture

[edit]-

The Favourites of the Emperor Honorius, John William Waterhouse, c. 1883

(Art Gallery of South Australia)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Probably Theodosius the Great and his sons Arcadius and Honorius

- ^ Inscription reads:

Florentib· d·d· [n·n· H]onorio [et]

Theodosio inc[lyti]s semper augg·

Iunius Valerius [Bellici]us v·c· p[r]aef· u[rb·]

vice sac·iud port[icum cum sc]r[i]ni[is]

Tellurensis secr[etarii tribunalibus]

adherentem red[integravit et] urbanae

sedi vetustatis h[o]nor[em resti]tuit - ^ Theodosius I (top), Arcadius (left), and Honorius (right)

- ^ d·d·d·n·n·n·auggg· ("Our Lords the Augusti") : Theodosius (centre), Arcadius (left), Honorius (right)

- ^ d·n· arcadius p·f· aug· ("Our Lord Arcadius, Pious Happy Augustus")

- ^ Inscription: ael· eudoxia aug· ("Aelia Eudocia Augusta")

- ^ Inscription: d·n· honorius p·f· aug· ("Our Lord Arcadius, Pious Happy Augustus"), from Hoxne hoard

- ^ Inscription:d·n· galla placidia p·f· aug· ("Our Lady Galla Placidia, Pious Happy Augusta") The reverse shows Victory and a crux gemmata

- ^ Theodosius II (centre) blessing Valentinian III (left) and Theodosius' daughter Licinia Eudoxia (right)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci Kienast, Dietmar (2017) [1990]. "Theodosius I". Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. pp. 323–326. ISBN 978-3-534-26724-8.

- ^ a b c d Bond, Sarah; Darley, Rebecca (2018a). "Valentinian I (321–75)". pp. 1546–1547. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8. Retrieved 2020-10-24, in Nicholson (2018)

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c Kienast, Dietmar (2017) [1990]. "Valentinianus". Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. pp. 313–315. ISBN 978-3-534-26724-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Kienast, Dietmar (2017) [1990]. "Gratianus". Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. pp. 319–320. ISBN 978-3-534-26724-8.

- ^ Bond, Sarah; Nicholson, Oliver (2018a). "Gratian (359–83)". pp. 677–678. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8. Retrieved 2020-10-25, in Nicholson (2018)

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Kienast, Dietmar (2017) [1990]. "Valentinianus II". Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. pp. 321–322. ISBN 978-3-534-26724-8.

- ^ a b Bond, Sarah (2018a). "Valentinian II (371–92)". p. 1547. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8. Retrieved 2020-10-25, in Nicholson (2018)

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b Groß-Albenhausen, Kirsten (2006). "Flacilla". Brill's New Pauly.

- ^ a b c Nathan, Geoffrey (2018a). "Galla Placidia, Aelia (c. 388–450)". p. 637. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8. Retrieved 2020-10-24, in Nicholson (2018)

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)

Bibliography

[edit]Books and theses

[edit]- Cameron, Averil; Garnsey, Peter, eds. (1998). The Cambridge Ancient History XIII: The Late Empire, A.D. 337–425. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30200-5. (see Cambridge Ancient History CAH)

- Blockley, R. C. (1998). The dynasty of Theodosius. pp. 111–137., in Cameron & Garnsey (1998)

- Curran, John (1998). From Jovian to Theodosius. pp. 78–110., in Cameron & Garnsey (1998)

- Cameron, Averil; Ward-Perkins, Bryan; Whitby, Michael, eds. (2000). The Cambridge Ancient History XIV: Late antiquity. Empire and successors, A.D. 425–600. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-32591-2.

- Kienast, Dietmar; Eck, Werner; Heil, Matthäus (2017) [1990]. Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie (in German) (6 ed.). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-534-26724-8.{{link note|note=excerpts at

- Frakes, Robert M (2006). "The dynasty of Constantine down to 363". In Lenski, Noel Emmanuel (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine. Cambridge University Press. pp. 91–108. ISBN 978-0-521-52157-4.

- Humphries, Mark (2019). "Family, Dynasty, and the Construction of Legitimacy from Augustus to the Theodosians". In Tougher, Shaun (ed.). The Emperor in the Byzantine World: Papers from the Forty-Seventh Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies. Taylor & Francis. pp. 13–27. ISBN 978-0-429-59046-7.

- Kulikowski, Michael (2006). Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45809-2.

- Kulikowski, Michael (2019). The Tragedy of Empire: From Constantine to the Destruction of Roman Italy. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-66013-7.

- Lee, A. D. (2013). From Rome to Byzantium AD 363 to 565. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-6835-9.

- McEvoy, Meaghan (2013). Child Emperor Rule in the Late Roman West, AD 367-455. OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-966481-8.

- McLynn, Neil B. (2014) [1994]. Ambrose of Milan: Church and Court in a Christian Capital. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-28388-6.

- Nicholson, Oliver, ed. (2018). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8. E-book: ISBN 978-0-19-256246-3. (see The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity)

- Bond, Sarah E (2018a). "Valentinian II". Valentinian II (371–92). Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 1547. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8., in Nicholson (2018)

- Bond, Sarah E; Darley, Rebecca (2018a). "Valentinian I". Valentinian I (321–75). Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 1546–1547. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8., in Nicholson (2018)

- Bond, Sarah E; Darley, Rebecca (2018b). "Valens". Valens (328–78). Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 1546. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8., in Nicholson (2018)

- Bond, Sarah E; Nicholson, Oliver (2018a). "Gratian". Gratian (359–83). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 677–678. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8., in Nicholson (2018)

- Nathan, Geoffrey S (2018a). "Galla Placidia, Aelia". Galla Placidia, Aelia (c. 388–450). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 637. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8., in Nicholson (2018)

- Nicholson, Oliver (2018a). Pannonian emperors. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 637. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8., in Nicholson (2018)

- Washington, Belinda (2015). The roles of imperial women in the Later Roman Empire (AD 306-455) (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh.

Articles and websites

[edit]- Johnson, Mark J. (1991). "On the Burial Places of the Valentinian Dynasty". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 40 (4): 501–506. JSTOR 4436217.

- Kulikowski, Michael (1 January 2016). "Henning Börm, Westrom. Von Honorius bis Justinian". Klio. 98 (1): 393–396. doi:10.1515/klio-2016-0033. S2CID 193005098.

- McEvoy, Meaghan (2016). "Constantia: The Last Constantinian". Antichthon. 50: 154–179. doi:10.1017/ann.2016.10. S2CID 151430655.

- Lendering, Jona (10 August 2020). "Valentinian Dynasty". Livius. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

External links

[edit]Theodosian dynasty

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Establishment

Rise of Theodosius I

Flavius Theodosius was born circa 346 in Cauca, within the Roman province of Gallaecia in Hispania.[5] He was the son of Theodosius the Elder, a high-ranking military officer who served as magister equitum praesentalis under Emperor Valentinian I from late 368 to early 375, and Thermantia, whose background remains obscure.[5] The elder Theodosius had distinguished himself in campaigns suppressing the Great Conspiracy in Britain around 367–369, restoring Roman control against Pictish, Scottish, and Saxon incursions, and later quelling revolts in Africa.[5] Theodosius began his military career accompanying his father, gaining experience in Britain during the 367/368 operations.[5] By late 374, he held the command of dux Moesiae Primae along the Danube frontier.[5] Following a Sarmatian defeat in Valeria province around 375/376, where he faced accusations of cowardice, Theodosius was compelled into retirement, withdrawing to his familial estates in Spain for nearly three years (circa 376–378); concurrently, his father was executed under unclear circumstances circa 375, likely tied to the political purges after Valentinian I's death on 17 November 375.[5] After Valentinian's passing and the ensuing instability, Theodosius was recalled to service, initially as dux Valeriae and then elevated to magister militum per Illyricum from 376 to 379, rebuilding Roman forces amid frontier threats.[5] The catastrophic Roman defeat at the Battle of Adrianople on 9 August 378, where Emperor Valens perished against the Goths, created a power vacuum in the East; Gratian, ruling the West, selected Theodosius—deemed the most capable senior Roman-born officer available—as his successor.[5] On 19 January 379, at Sirmium, Gratian proclaimed Theodosius emperor (Augustus) of the Eastern provinces, tasking him with stabilizing the Gothic crisis; on 1 September 379, Gratian ceded the vital dioceses of Illyricum to Theodosius's authority to bolster recruitment and logistics.[5] This appointment marked the culmination of Theodosius's ascent from provincial soldier to imperial ruler, leveraging his proven administrative and martial skills in a moment of existential peril for the empire.[5]Consolidation of Power (379–395)

Theodosius I, a general of Hispanic origin, was elevated to the rank of Augustus in the East by Western Emperor Gratian on 19 January 379, tasked with restoring order after the catastrophic Roman defeat at the Battle of Adrianople in 378, which had left the Balkans vulnerable to Gothic incursions.[5] Drawing on his experience from prior service under Valentinian I, Theodosius rapidly assembled a new army incorporating Gothic and other barbarian recruits, achieving a significant victory over Gothic forces in the summer of 380 near Constantinople.[5] This success enabled him to enter the city in November 380, suppressing remnants of Valens' Arian supporters and consolidating control over the eastern provinces through a combination of military enforcement and administrative appointments loyal to his regime.[5] Religious policy formed a cornerstone of Theodosius' consolidation efforts, as he sought to unify the empire ideologically amid doctrinal divisions. On 27 February 380, Theodosius, alongside Gratian and Valentinian II, issued the Edict of Thessalonica from the city where he had recently recovered from a near-fatal illness and been baptized into Nicene Christianity; the edict declared the Nicene faith—upholding the Trinity as defined by the Council of Nicaea in 325—the sole orthodox doctrine, threatening divine and imperial punishment against heretics, particularly Arians, while tolerating pagans temporarily.[6][7] This measure, enforced through councils like that of Constantinople in 381 which reaffirmed Nicene orthodoxy and expanded its creed, marginalized Arianism within the eastern church and military, reducing internal factionalism that had weakened Valens' rule.[8] By 391–392, further edicts banned pagan sacrifices and temple rituals, though enforcement varied regionally, prioritizing Christian cohesion as a bulwark against barbarian threats.[5] Military campaigns against usurpers further solidified Theodosius' authority over the undivided empire. In 383, Magnus Maximus, proclaimed emperor by British legions, invaded Gaul, defeating and killing Gratian; by 387, Maximus had seized control from young Valentinian II in Italy, prompting Theodosius to intervene.[5] Launching a joint expedition with Valentinian in summer 388, Theodosius' forces triumphed at the Battle of Siscia and decisively at Poetovio (modern Ptuj) in Pannonia, capturing Aquileia where Maximus was executed on 28 August 388, restoring Valentinian II and affirming Theodosius' dominance across both halves of the empire.[5] A brief Gothic treaty in 382 had earlier settled federate groups in Thrace as a pragmatic buffer, providing recruits but sowing long-term tensions; Theodosius exploited these in 394 against the Western usurper Eugenius, backed by Arbogast after Valentinian II's murder in 392.[5] At the Battle of the Frigidus on 5–6 September 394, Theodosius' army, despite heavy losses from wind and terrain, routed Eugenius' forces, killing him and Arbogast, thus eliminating internal rivals and securing nominal unity under Theodosian rule.[5] To ensure dynastic continuity, Theodosius elevated his sons: Arcadius, born circa 377 to first wife Aelia Flaccilla, was proclaimed Augustus on 19 January 383, positioning him as heir in the East; Honorius, born 384, received the same honor on 23 January 393 at the age of nine, groomed for the West amid ongoing instability.[5] These appointments, accompanied by marriages like Theodosius' to Galla (Valentinian I's daughter) in 387, intertwined Theodosian and Valentinian lines, fostering legitimacy through blood ties while decentralizing authority; by his death on 17 January 395 at Milan, Theodosius had transformed a fractured imperium into a dynastically anchored entity, though reliant on barbarian generals like Stilicho and Rufinus for execution.[5] Administrative measures, including tax reforms and senatorial promotions, supported this framework, but causal pressures from migration and fiscal strain presaged future divisions.[5]Division and Parallel Reigns

Arcadius in the East (395–408)

Upon the death of Theodosius I on 17 January 395, the Roman Empire was partitioned, with Arcadius, born circa 377 and thus approximately 18 years old, receiving the eastern provinces centered on Constantinople, while his younger brother Honorius took the west.[9] Initial authority rested with the praetorian prefect Rufinus, who had orchestrated Arcadius' proclamation as Augustus in 383 and effectively controlled the young emperor amid Gothic incursions led by Alaric, which devastated Thrace and Greece in 395.[9] [10] Rufinus faced accusations of complicity with Alaric, possibly to weaken western influence under Stilicho; on 27 November 395, he was assassinated by Gothic troops under Gainas during a parade outside Constantinople, an act likely instigated by Stilicho's agents.[9] Eutropius, a palace eunuch and chamberlain, swiftly consolidated power, eliminating Rufinus' allies and arranging Arcadius' marriage to Aelia Eudoxia, daughter of a Frankish general, on 27 April 395 to secure his position against potential rivals.[9] [10] Eutropius repelled a Hunnic incursion into the Balkans in 397–398, earning the consulate in 399 as the first eunuch to hold it, but his favor toward Persians and perceived failures alienated Gothic federates.[9] In 399, the Gothic commander Tribigild revolted in Asia Minor, demanding Eutropius' dismissal; Gainas, magister militum per Thracias, was dispatched against him but defected, marching on Constantinople and forcing Eutropius' exile and execution in autumn 399.[9] [11] Gainas entered Constantinople in early 400, securing appointment as magister militum praesentalis and demanding Gothic churches and quartering rights, but popular unrest erupted in July 400 when citizens, fearing Gothic dominance, massacred around 7,000 Germanic troops and civilians.[9] Gainas fled across the Danube, where Hunnic forces under Uldin defeated and killed him later in 400, restoring stability but eroding trust in Germanic officers.[9] Eudoxia, elevated to Augusta on 9 January 400, exerted growing influence, bearing Arcadius' heir Theodosius on 10 April 401—who was proclaimed Augustus at eight months—and other children, including Flaccilla, Pulcheria, Marina, and Arcadia.[9] [12] Eudoxia's prominence fueled tensions with Patriarch John Chrysostom, whose sermons against clerical and imperial excess, including a pointed oration on the biblical Jezebel after Eudoxia's silver statue was erected near his church in 403, were perceived as personal attacks.[9] [12] A synod at the Oak in 403 deposed Chrysostom on charges of insubordination and heresy, prompting riots; briefly reinstated, he was permanently exiled in 404 after fires damaged the city, attributed by his supporters to imperial intrigue.[9] Eudoxia died on 6 October 404, possibly from complications of a miscarriage.[9] From 404, praetorian prefect Anthemius stabilized administration, fortifying Constantinople's walls and fostering reconciliation with the west through a joint consulship with Stilicho in 405.[9] Arcadius, described by contemporaries as pious yet indolent and detached from governance, maintained nominal orthodoxy, including edicts suppressing paganism and heresy.[9] He died on 1 May 408 at age 31, likely from natural causes, succeeded seamlessly by the seven-year-old Theodosius II under Anthemius' regency.[9]Honorius in the West (395–423)

Following the death of Theodosius I on 17 January 395, the Roman Empire was partitioned, with the ten-year-old Honorius assuming rule over the Western provinces while his brother Arcadius governed the East.[13] The regency fell to Flavius Stilicho, a half-Vandal general who had risen under Theodosius and married his niece Serena, granting Stilicho de facto control as magister militum praesentalis.[13] In 398, Honorius wed Stilicho's daughter Maria to solidify the alliance, though she died childless around 407; he later married her sister Thermantia in 408, yielding no heirs.[13] Stilicho prioritized defending Italy against barbarian incursions, notably repelling Alaric's Visigoths who invaded in 401–402.[13] At the Battle of Pollentia on Easter Sunday 402, Stilicho's forces surprised and defeated Alaric, capturing his baggage train and family, though Alaric escaped; a subsequent victory at Verona forced the Visigoths northward.[13] For security, Honorius relocated the court from Milan to marsh-girded Ravenna in 402.[13] Stilicho then crushed Radagaisus' Gothic-Alan-Sarmatian host of perhaps 400,000 near Florence in 406, selling many captives into slavery, but this diverted troops, enabling Vandal, Alan, and Suebi crossings of the frozen Rhine on 31 December 406, fracturing Gaul's defenses.[13] http://www.plekos.uni-muenchen.de/2019/r-doyle.pdf Stilicho's downfall came amid court intrigues fueled by Eastern influences and fears of his ambitions.[14] In 408, after negotiations with Alaric stalled, eunuch Olympius orchestrated a coup; Stilicho fled to a church but was executed on 22 August on Honorius' orders, with his followers' families massacred.[13] Chaos ensued: Alaric invaded Italy again in 408, extorting 5,000 pounds of gold and 30,000 pounds of silver from a Senate coerced into recognizing puppet emperor Priscus Attalus in 409.[14] Alaric deposed Attalus, besieged Ravenna unsuccessfully, then Rome thrice before sacking it on 24 August 410— the first such breach in eight centuries—though restrained looting spared major destruction.[13] http://www.plekos.uni-muenchen.de/2019/r-doyle.pdf Alaric died soon after, and his successor Ataulf led the Visigoths to Gaul in 412.[13] Honorius' reign saw eight major usurpations, including Constantine III in Britain and Gaul (407–411), Jovinus in Gaul (413), and Maximus in Spain (409, 420–422), reflecting provincial fragmentation and weak central authority.[14] In 417, general Constantius III, who suppressed Attalus and Alaric's remnants, married Honorius' sister Galla Placidia and became co-emperor in February 421 before dying in September.[13] Honorius himself succumbed to dropsy (edema) on 15 August 423 at age 38, leaving no successor and prompting the primicerius notariorum Joannes' brief usurpation until Eastern intervention installed Valentinian III in 425.[13] Despite crises like Britain's loss and Danube ungovernability, Honorius' 28-year tenure endured, sustained by loyal generals amid systemic military and administrative strains.[14]Continuation and Decline

Theodosius II's Reign (408–450)

Theodosius II ascended to the throne of the Eastern Roman Empire on May 1, 408, at the age of seven, following the death of his father, Arcadius.[15] The initial regency was managed by Anthemius, the praetorian prefect of the East, who supervised military and administrative affairs while a palace eunuch named Antiochus handled the young emperor's personal care. Under Anthemius's direction, the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople were constructed between approximately 408 and 413, forming a double line of fortifications with a moat that significantly enhanced the city's defenses against invasions.[16] In 414, Anthemius transferred the regency to Theodosius's elder sister, Aelia Pulcheria, then aged fifteen, who was proclaimed Augusta and exerted profound influence over the court.[17] Pulcheria, a devout Christian who had vowed perpetual virginity along with her sisters, fostered an austere, pious atmosphere at the palace, emphasizing religious orthodoxy and moral discipline.[15] Despite her dominance, Theodosius married Athenais (later Aelia Eudocia), a Greek scholar and daughter of an Athenian philosopher, in 421; Eudocia's intellectual inclinations reportedly encouraged cultural initiatives, though Pulcheria retained substantial sway.[18] Administrative reforms marked the reign's intellectual achievements. On February 27, 425, Theodosius established the University of Constantinople, endowing it with 31 professorial chairs—fifteen in Latin and sixteen in Greek—covering law, philosophy, medicine, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music, and rhetoric, thereby promoting higher learning amid the empire's Christian framework.[18] In 429, he commissioned a panel of jurists to compile imperial constitutions from the time of Constantine I onward, resulting in the Codex Theodosianus, a systematic legal code promulgated on February 15, 438, and extended to the Western Empire, which standardized jurisprudence and reinforced state authority over pagan practices and heresies.[19] Religiously, Theodosius II convened the Council of Ephesus in 431 to adjudicate Christological disputes, particularly the teachings of Nestorius, patriarch of Constantinople, who emphasized the distinction between Christ's divine and human natures.[20] The council, dominated by Cyril of Alexandria's faction, deposed Nestorius and affirmed the title Theotokos ("Mother of God") for Mary, though procedural irregularities and imperial vacillation—reflecting Theodosius's initial hesitation to condemn Nestorius—prolonged divisions, as evidenced by the subsequent Nestorian schism and Persian support for the exiles.[21] Militarily, the reign faced persistent threats. Relations with Sassanid Persia soured in 420 over the persecution of Christians in Persian territories, escalating into border conflicts from 421 to 422, which ended in a fragile peace allowing Roman forces to redirect attention elsewhere.[22] Hunnic incursions under Rugila and later Attila proved more devastating; after raids in the 420s, a 435 treaty ceded Roman territory north of the Danube and imposed annual tribute of 350 pounds of gold, revised upward to 2,100 pounds by 443 following Attila's invasions of the Balkans in 441–447, which sacked over 70 cities and extracted further concessions despite the Theodosian Walls' resilience at Constantinople. These payments, justified in Roman sources as pragmatic to preserve resources, strained finances but averted total collapse, with Pulcheria advocating defensive strategies over offensive campaigns. Theodosius II died on July 28, 450, after falling from his horse during a hunting accident near Constantinople, leaving no direct male heir.[15] Pulcheria swiftly arranged the marriage of the new emperor, Marcian, to herself, ensuring dynastic continuity while prioritizing fiscal restraint and orthodoxy in the ensuing transition.[15]Valentinian III and the West's Fall (425–455)

Valentinian III, born on 2 July 419 as the son of Galla Placidia (daughter of Theodosius I) and Constantius III, was proclaimed Western Roman emperor on 23 October 425 at age six, following the execution of usurper Joannes with military aid from his cousin, Eastern emperor Theodosius II.[23] Effective governance during his minority fell to Galla Placidia as regent from 425 until 437, a period marked by her efforts to consolidate Theodosian legitimacy amid factional strife.[24] This regency saw the relocation of the court to Ravenna and initial administrative reforms, including educational reorganizations, but was undermined by rivalries among military leaders that exacerbated territorial erosion.[23] A central conflict arose between generals Flavius Aetius and Count Boniface, whom Aetius deceived into defying imperial orders, prompting Boniface to invite Vandal forces under Gaiseric into Africa in 429 as allies. This miscalculation enabled the Vandals to overrun North Africa, capturing Carthage on 19 October 439 and severing a vital grain supply and revenue source that comprised roughly half of the Western treasury, directly contributing to fiscal collapse and inability to maintain field armies.[23] The ensuing civil war in 432 pitted Boniface against Aetius; Boniface won at the Battle of Rimini but succumbed to wounds, allowing Aetius—bolstered by Hunnic mercenaries—to dominate as magister militum and patrician, effectively controlling policy through Valentinian's adulthood.[24][25] Under Aetius' command, Roman forces achieved temporary successes, such as defeating the Burgundians in 436 and repelling Hunnic invasions at the Catalaunian Plains on 20 June 451 in coalition with Visigoths, halting Attila's advance into Gaul.[23] Yet, systemic weaknesses persisted: Britain was abandoned by 410 with no reclamation; Gaul fragmented among Franks, Visigoths, and Alans; Spain fell to Suebi and Vandals by the 430s; and Vandal raids devastated Sicily and Italy's coasts.[24] Valentinian's personal rule after 437 emphasized theological disputes—such as the 445 edict enforcing orthodoxy against Pelagians and Manichaeans—over military revitalization, compounded by his marriage to Theodosius II's daughter Licinia Eudoxia on 29 October 437, which aimed to reinforce dynastic ties but yielded no strategic gains.[23] The Hunnic threat peaked in 452 with Attila's incursion into Italy, sacking Aquileia and reaching the Po Valley before papal negotiations prompted withdrawal, exposing reliance on diplomacy absent robust legions.[23] On 21 September 454, Valentinian personally struck down Aetius during a budgetary review in the Palace of Rome, motivated by accumulated resentments and fears of overreach, depriving the empire of its last capable defender.[24] Without Aetius, vulnerabilities mounted; Valentinian's assassination on 16 March 455 by Aetius' disgruntled bodyguards Optila and Trausta, while practicing archery on the Campus Martius, ended Theodosian rule in the West, triggering Petronius Maximus' brief usurpation and the Vandal sack of Rome from 2 to 16 June 455, after which imperial authority contracted to Italy amid unchecked barbarian federates.[23] This sequence of internal purges and external predation underscored causal failures in central fiscal-military integration, rendering the Western Empire indefensible beyond nominal suzerainty.[24]Dynastic Composition

Core Imperial Emperors

The core imperial emperors of the Theodosian dynasty were Theodosius I, his sons Arcadius and Honorius, and grandson Theodosius II, who collectively ruled the Roman Empire from 379 to 450, spanning both Eastern and Western halves after the division in 395.[2][1] This patrilineal line originated with Theodosius I, son of the general Theodosius the Elder, and emphasized dynastic continuity amid barbarian pressures and internal administrative challenges.[2] Theodosius I (379–395) ascended as emperor in the East on January 19, 379, following the defeat at Adrianople, and extended his authority over the West from 388 after defeating usurpers Magnus Maximus and Eugenius.[1] His reign unified the empire temporarily, suppressed pagan practices through edicts like the 391 ban on sacrifices, and promoted Nicene Christianity as the state religion via the 380 Edict of Thessalonica.[26] He died on January 17, 395, dividing the realm between Arcadius in the East and Honorius in the West to secure familial rule.[2] Arcadius (395–408) governed the Eastern Empire as senior Augustus, though effective power often rested with ministers like Rufinus and Eutropius amid Gothic threats under Alaric.[1] His rule maintained relative stability in the wealthier East, fostering urban development in Constantinople, but saw tensions with the Western court under Stilicho. Arcadius died on May 25, 408, succeeded by his son Theodosius II.[2] Honorius (395–423) held the Western Empire, relying heavily on generals like Stilicho until his execution in 408, during which Rome endured sacks by Alaric's Visigoths in 410. His reign marked accelerating territorial losses, including Britain and Gaul provinces, yet preserved nominal imperial authority until his death on August 15, 423.[1][2] Theodosius II (408–450), proclaimed co-emperor in 402 as an infant, assumed sole rule in the East after Arcadius, overseeing the compilation of the Theodosian Code in 438 to systematize imperial legislation from Constantine onward.[27] His long reign fortified Constantinople with walls bearing his name and navigated theological disputes, though military setbacks included the 441 loss of North African territories to Vandals.[26] He died on July 28, 450, from a riding accident, ending direct male-line rule in the East.[2]Empresses and Female Influencers

Aelia Flaccilla, first wife of Theodosius I, bore him three children who survived infancy: Arcadius, Honorius, and Pulcheria, thereby securing the dynastic line's core male heirs.[28] Of Spanish Roman aristocratic descent, she died in 386 and was commemorated for her charitable acts toward the poor and her advocacy for Nicene orthodoxy, as recorded by church historian Sozomen, who noted her intervention to prevent Theodosius from meeting the heretic Eunomius.[29] Her influence extended to religious policy, aligning with Theodosius's eventual enforcement of Trinitarian Christianity, though primary agency in state affairs remained with the emperor.[28] Galla, daughter of Valentinian I and second wife of Theodosius I, married him in 387 following Flaccilla's death and gave birth to Galla Placidia around 392–393, linking the Theodosian line to the prior Valentinian dynasty through intermarriage.[30] She died in 394 shortly after childbirth, exerting limited recorded political influence but contributing to dynastic continuity via her offspring.[31]Aelia Eudoxia, daughter of the Frankish Roman general Bauto (consul in 385), married Arcadius in 395 and was elevated to Augusta in 400, wielding significant influence over eastern court politics during his reign.[32] She bore Arcadius five children, including Theodosius II, Flaccilla, Pulcheria, Marina, and Arcadia, with four reaching adulthood, thus propagating the dynasty eastward.[33] Her rivalry with Patriarch John Chrysostom led to his exile in 404, prompted by his criticism of her ostentatious lifestyle and alleged role in the violence against protesting monks, reflecting her assertive defense of imperial prerogatives against ecclesiastical challenges.[33] Eudoxia died on October 6, 404, from complications of a miscarriage, curtailing her direct sway but leaving a legacy of coins depicting her crowned by the divine hand, symbolizing her augmented public role.[32] Aelia Pulcheria, eldest daughter of Arcadius and Eudoxia (born c. 398–399), assumed de facto regency over her brother Theodosius II from 414 at age 15, after vowing perpetual virginity with her sisters to prioritize imperial governance over personal unions.[34] Proclaimed Augusta that year, she directed administrative and religious policies, including the promotion of Marian devotion and orthodoxy, countering Nestorianism at the Council of Ephesus in 431 through her orchestration of Cyril of Alexandria's support.[35] Her influence persisted into Theodosius II's adulthood, shaping palace eunuchs' roles and foreign diplomacy, until she married Marcian in 450 following Theodosius's death, briefly co-ruling before her own death in 453; contemporaries credited her with stabilizing the eastern empire amid weak male leadership.[34] Aelia Eudocia (born Athenais c. 401), daughter of the Athenian philosopher Leontius, converted from paganism and married Theodosius II in 421, adopting her name to signify imperial favor.[36] As Augusta, she bore Licinia Eudoxia (future wife of Valentinian III) and possibly two other daughters, while patronizing literature and construction, including churches and walls in Jerusalem and Antioch during her pilgrimage c. 438–439.[37] Tensions with Pulcheria escalated, leading to Eudocia's exile to Jerusalem c. 443 amid accusations of adultery (later dismissed as court intrigue), where she continued charitable works until her death c. 460; her literary output, including a Homeric centos on biblical themes, underscored her intellectual influence in a dynasty increasingly intertwined with Christian theology.[36][37] Galla Placidia, daughter of Theodosius I and Galla (c. 392–450), emerged as the dynasty's pivotal western influencer after her captivity by Alaric during the 410 sack of Rome and marriage to Visigoth king Ataulf in 414, which briefly allied barbarian and Roman interests before his assassination.[30] Remarried to Constantius III in 417, she bore Valentinian III (born 419), securing Theodosian succession in the West, and served as regent from 425 to 437 during his minority, directing military campaigns against usurpers like John and negotiating Hunnic treaties while residing in Ravenna.[30] Her theological interventions supported Leo I against Eutychianism, commissioning churches like Santa Croce in Ravenna; despite criticisms of extravagance in sources like Olympiodorus, her regency preserved dynastic legitimacy amid barbarian incursions until her death in 450.

![Missorium of Theodosius with three Theodosian emperors[a] of Theodosian](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/54/Disco_de_Teodosio.jpg/250px-Disco_de_Teodosio.jpg)