Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cervical vertebrae

View on Wikipedia| Cervical vertebrae | |

|---|---|

| |

A human cervical vertebra | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vertebrae cervicales |

| MeSH | D002574 |

| TA98 | A02.2.02.001 |

| TA2 | 1032 |

| FMA | 9915 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (sg.: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae.[1] In sauropsid species, the cervical vertebrae bear cervical ribs. In lizards and saurischian dinosaurs, the cervical ribs are large; in birds, they are small and completely fused to the vertebrae. The vertebral transverse processes of mammals are homologous to the cervical ribs of other amniotes.[citation needed] Most mammals have seven cervical vertebrae, with the only three known exceptions being the manatee with six, the two-toed sloth with five or six, and the three-toed sloth with nine.[2][3]

In humans, cervical vertebrae are the smallest of the true vertebrae and can be readily distinguished from those of the thoracic or lumbar regions by the presence of a transverse foramen, an opening in each transverse process, through which the vertebral artery, vertebral veins, and inferior cervical ganglion pass. The remainder of this article focuses on human anatomy.

Structure

[edit]

By convention, the cervical vertebrae are numbered, with the first one (C1) closest to the skull and higher numbered vertebrae (C2–C7) proceeding away from the skull and down the spine. The general characteristics of the third through sixth cervical vertebrae are described here. The first, second, and seventh vertebrae are extraordinary, and are detailed later.

- The bodies of these four vertebrae are small, and broader from side to side than from front to back.

- The anterior and posterior surfaces are flattened and of equal depth; the former is placed on a lower level than the latter, and its inferior border is prolonged downward, so as to overlap the upper and forepart of the vertebra below.

- The upper surface is concave transversely, and presents a projecting lip on either side.

- The lower surface is concave from front to back, convex from side to side, and presents laterally shallow concavities that receive the corresponding projecting lips of the underlying vertebra.

- The pedicles are directed laterally and backward, and attach to the body midway between its upper and lower borders, so that the superior vertebral notch is as deep as the inferior, but it is, at the same time, narrower.

- The laminae are narrow and thinner above than below; the vertebral foramen is large and of a triangular form.

- The spinous process is short and bifid, the two divisions being often of unequal size. Because the spinous processes are so short, certain superficial muscles (the trapezius and splenius capitis) attach to the nuchal ligament rather than directly to the vertebrae; the nuchal ligament itself attaching to the spinous processes of C2–C7 and to the posterior tubercle of the atlas.

- The superior and inferior articular processes of cervical vertebrae have fused on either or both sides to form articular pillars, columns of bone that project laterally from the junction of the pedicle and lamina.

- The articular facets are flat and of an oval form:

- the superior face backward, upward, and slightly medially.

- the inferior face forward, downward, and slightly laterally.

- The transverse processes are each pierced by the transverse foramen also known as the foramen transversarium, which, in the upper six vertebrae, gives passage to the vertebral artery and vein, as well as a plexus of sympathetic nerves. Each process consists of an anterior and a posterior part. These two parts are joined, outside the foramen, by a bar of bone that exhibits a deep sulcus on its upper surface for the passage of the corresponding spinal nerve.

- The anterior portion is the homologue of the rib in the thoracic region, and is therefore named the costal process or costal element. It arises from the side of the body, is directed laterally in front of the foramen, and ends in a tubercle, the anterior tubercle.

- The posterior part, the true transverse process, springs from the vertebral arch behind the foramen and is directed forward and laterally; it ends in a flattened vertical tubercle, the posterior tubercle.

The anterior tubercle of the sixth cervical vertebra is known as the carotid tubercle or Chassaignac tubercle (for Édouard Chassaignac). This separates the carotid artery from the vertebral artery and the carotid artery can be massaged against this tubercle to relieve the symptoms of supraventricular tachycardia. The carotid tubercle is also used as a landmark for anaesthesia of the brachial plexus and cervical plexus.

The cervical spinal nerves emerge from above the cervical vertebrae. For example, the cervical spinal nerve 3 (C3) passes above C3.

Atlas and axis

[edit]The atlas (C1) and axis (C2) are the two topmost vertebrae.

The atlas (C1) is the topmost vertebra and along with the axis forms the joint connecting the skull and spine. It lacks a vertebral body, spinous process, and discs either superior or inferior to it. It is ring-like and consists of an anterior arch, posterior arch, and two lateral masses.

The axis (C2) forms the pivot on which the atlas rotates. The most distinctive characteristic of this bone is the strong odontoid process (dens) that rises perpendicularly from the upper surface of the body and articulates with C1. The body is deeper in front than behind, and prolonged downward anteriorly so as to overlap the upper and front part of the third vertebra.

Vertebra prominens

[edit]

The vertebra prominens, or C7, has a distinctive long and prominent spinous process, which is palpable from the skin surface. Sometimes, the seventh cervical vertebra is associated with an abnormal extra rib, known as a cervical rib, which develops from the anterior root of the transverse process. These ribs are usually small, but may occasionally compress blood vessels (such as the subclavian artery or subclavian vein) or nerves in the brachial plexus, causing pain, numbness, tingling, and weakness in the upper limb, a condition known as thoracic outlet syndrome. Very rarely, this rib occurs in a pair.

The long spinous process of C7 is thick and nearly horizontal in direction. It is not bifurcated, and ends in a tubercle that the ligamentum nuchae attaches to. This process is not always the most prominent of the spinous processes, being found only about 70% of the time, C6 or T1 can sometimes be the most prominent.

The transverse processes are of considerable size; their posterior roots are large and prominent, while the anterior are small and faintly marked. The upper surface of each usually has a shallow sulcus for the eighth spinal nerve, and its extremity seldom presents more than a trace of bifurcation.

The transverse foramen may be as large as that in the other cervical vertebrae, but it is generally smaller on one or both sides; occasionally, it is double, and sometimes it is absent.

On the left side, it occasionally gives passage to the vertebral artery; more frequently, the vertebral vein traverses it on both sides, but the usual arrangement is for both artery and vein to pass in front of the transverse process, not through the foramen.

Function

[edit]The movement of nodding the head takes place predominantly through flexion and extension at the atlanto-occipital joint between the atlas and the occipital bone. However, the cervical spine is comparatively mobile, and some component of this movement is due to flexion and extension of the vertebral column itself. This movement between the atlas and occipital bone is often referred to as the "yes joint", owing to its nature of being able to move the head in an up-and-down fashion.

The movement of shaking or rotating the head left and right happens almost entirely at the joint between the atlas and the axis, the atlanto-axial joint. A small amount of rotation of the vertebral column itself contributes to the movement. This movement between the atlas and axis is often referred to as the "no joint", owing to its nature of being able to rotate the head in a side-to-side fashion.

Clinical significance

[edit]Cervical degenerative changes arise from conditions such as spondylosis, stenosis of intervertebral discs, and the formation of osteophytes. The changes are seen on radiographs, which are used in a grading system from 0–4 ranging from no changes (0) to early with minimal development of osteophytes (1) to mild with definite osteophytes (2) to moderate with additional disc space stenosis or narrowing (3) to the stage of many large osteophytes, severe narrowing of the disc space, and more severe vertebral end plate sclerosis (4).[5][6][7]

Injuries to the cervical spine are common at the level of the second cervical vertebrae, but neurological injury is uncommon. C4 and C5 are the areas that see the highest amount of cervical spine trauma.[8]

If it does occur, however, it may cause death or profound disability, including paralysis of the arms, legs, and diaphragm, which leads to respiratory failure.

Common patterns of injury include the odontoid fracture and the hangman's fracture, both of which are often treated with immobilization in a cervical collar or halo brace.

A common practice is to immobilize a patient's cervical spine to prevent further damage during transport to hospital. This practice has come under review recently as incidence rates of unstable spinal trauma can be as low as 2% in immobilized patients. In clearing the cervical spine, Canadian studies have developed the Canadian C-Spine Rule (CCR) for physicians to decide who should receive radiological imaging.[9]

Landmarks

[edit]The vertebral column is often used as a marker of human anatomy. This includes:

- At C1, base of the nose and the hard palate

- At C2, the teeth of a closed mouth

- At C3, the mandible and hyoid bone

- At C4, the common carotid artery bifurcates.

- From C4–5, the thyroid cartilage[10]

- From C6–7, the cricoid cartilage[10]

- At C6, the oesophagus becomes continuous with the laryngopharynx and also where the larynx becomes continuous with the trachea. It is also the level where the carotid pulse can be palpated against the transverse process of the C6 vertebrae.

Additional images

[edit]-

Position of cervical vertebrae (shown in red). Animation.

-

Illustration of cervical vertebrae

-

Shape of cervical vertebrae (shown in blue and yellow). Animation.

-

3D image

-

Cervical vertebrae, lateral view (shown in blue and yellow)

-

Vertebral column

-

Vertebral column

-

X-ray of cervical vertebrae

-

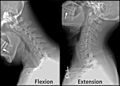

X-ray of cervical spine in flexion and extension

-

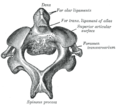

First cervical vertebra, or atlas

-

Second cervical vertebra, or epistropheus, from above

-

Second cervical vertebra, epistropheus, or axis, from the side

-

Seventh cervical vertebra

-

Posterior atlanto-occipital membrane and atlantoaxial ligament

-

Median sagittal section through the occipital bone and first three cervical vertebrae

-

Section of the neck at about the level of the sixth cervical vertebra

-

Anterior view of cervical spine showing the vertebral arteries along with the spinal nerves. See this in 3d here.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 97 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 97 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Schilling, N (10 February 2011). "Evolution of the axial system in craniates: morphology and function of the perivertebral musculature". Frontiers in Zoology. 8 (4): 3–4. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-8-4. PMC 3041741. PMID 21306656.

- ^ Varela-Lasheras, Irma; Bakker, Alexander J; Van Der Mije, Steven D; Metz, Johan AJ; Van Alphen, Joris; Galis, Frietson (2011). "Breaking evolutionary and pleiotropic constraints in mammals: On sloths, manatees and homeotic mutations". EvoDevo. 2: 11. doi:10.1186/2041-9139-2-11. PMC 3120709. PMID 21548920.

- "Sticking their necks out for evolution: Why sloths and manatees have unusually long (or short) necks". ScienceDaily (Press release). May 6, 2011.

- ^ Galis, Frietson (1999). "Why do almost all mammals have seven cervical vertebrae? Developmental constraints, Hox genes, and cancer". J. Exp. Zool. 285 (1): 19–26. Bibcode:1999JEZ...285...19G. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19990415)285:1<19::AID-JEZ3>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10327647.

- ^ Hillis, David M. (May 2011). Principles of Life. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 280–. ISBN 978-1-4641-6298-5. Archived from the original on 2018-05-06.

- ^ Ofiram, Elisha; Garvey, Timothy A; Schwender, James D; Denis, Francis; Perra, Joseph H; Transfeldt, Ensor E; Winter, Robert B; Wroblewski, Jill M (2009). "Cervical degenerative index: a new quantitative radiographic scoring system for cervical spondylosis with interobserver and intraobserver reliability testing". Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 10 (1): 21–26. doi:10.1007/s10195-008-0041-3. PMC 2657349. PMID 19384631.

- ^ Garfin, Steven R; Bono, Christopher M. "Degenerative Cervical Spine Disorders". spineuniverse. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- ^ Christie, A; Läubli, R; Guzman, R; Berlemann, U; Moore, R J; Schroth, G; Vock, P; Lövblad, K O (2005). "Degeneration of the cervical disc: histology compared with radiography and magnetic resonance imaging" (PDF). Neuroradiology. 47 (10): 721–729. doi:10.1007/s00234-005-1412-6. PMID 16136264. S2CID 10970503.

- ^ 2012 Annual Report Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine, Table 64, page 66

- ^ "Canadian C-Spine Rule - Emergency Medicine Research - Ottawa Hospital Research Institute". www.ohri.ca. Archived from the original on 14 May 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ a b MedicalMnemonics.com: 3548

External links

[edit]- Diagram at kenyon.edu

- Cervical Spine Anatomy

- Mnemonic for Landmarks

- Cervical vertebra quiz

- Cervical vertebrae[permanent dead link] - BlueLink Anatomy - University of Michigan Medical School