Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

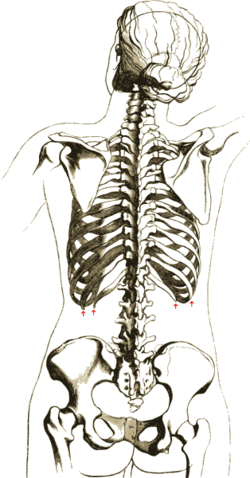

Rib cage

View on Wikipedia| Rib cage | |

|---|---|

Human rib cage | |

Animation of the rib cage | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cavea thoracis |

| MeSH | D000070602 |

| TA98 | A02.3.04.001 |

| TA2 | 1096 |

| FMA | 7480 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The rib cage or thoracic cage is an endoskeletal enclosure in the thorax of most vertebrates that comprises the ribs, vertebral column and sternum, which protect the vital organs of the thoracic cavity, such as the heart, lungs and great vessels and support the shoulder girdle to form the core part of the axial skeleton.

A typical human thoracic cage consists of 12 pairs of ribs and the adjoining costal cartilages, the sternum (along with the manubrium and xiphoid process), and the 12 thoracic vertebrae articulating with the ribs. The thoracic cage also provides attachments for extrinsic skeletal muscles of the neck, upper limbs, upper abdomen and back, and together with the overlying skin and associated fascia and muscles, makes up the thoracic wall.

In tetrapods, the rib cage intrinsically holds the muscles of respiration (diaphragm, intercostal muscles, etc.) that are crucial for active inhalation and forced exhalation, and therefore has a major ventilatory function in the respiratory system.

Structure

[edit]There are thirty-three vertebrae in the human vertebral column. The rib cage is associated with TH1−TH12. Ribs are described based on their location and connection with the sternum. All ribs are attached posteriorly to the thoracic vertebrae and are numbered accordingly one to twelve. Ribs that articulate directly with the sternum are called true ribs, whereas those that do not articulate directly are termed false ribs. The false ribs include the floating ribs (eleven and twelve) that are not attached to the sternum at all.

Attachment

[edit]The terms true ribs and false ribs describe rib pairs that are directly or indirectly attached to the sternum respectively. The first seven rib pairs known as the fixed or vertebrosternal ribs are the true ribs (Latin: costae verae) as they connect directly to the sternum via their own individual costal cartilages. The next five pairs (eighth to twelfth) are the false ribs (Latin: costae spuriae) or vertebrochondral ribs, which do not connect directly to the sternum. The first three pairs of vertebrochondral ribs (eighth to tenth) connect indirectly to the sternum via the costal cartilages of the ribs above them,[1][2] and the overall elasticity of their articulations allows the bucket handle movements of the rib cage essential for respiratory activity.

The phrase floating rib (Latin: costae fluctuantes) or vertebral rib refers to the two lowermost (the eleventh and twelfth) rib pairs; so-called because they are attached only to the vertebrae and not to the sternum or any of the costal cartilages. These ribs are relatively small and delicate, and include a cartilaginous tip.[3]

The spaces between the ribs are known as intercostal spaces; they contain the instrinsic intercostal muscles and the neurovascular bundles containing intercostal nerves, arteries and veins.[4] The superficial surface of the rib cage is covered by the thoracolumbar fascia, which provides external attachments for the neck, back, pectoral and abdominal muscles.

-

Human rib cage - CT scan (parallel projection (left) and perspective projection (right))

-

true / fixed ribsfalse ribsfalse and floating ribs

Parts of rib

[edit]

Each rib consists of a head, neck, and a shaft. All ribs are attached posteriorly to the thoracic vertebrae. They are numbered to match the vertebrae they attach to – one to twelve, from top (T1) to bottom. The head of the rib is the end part closest to the vertebra with which it articulates. It is marked by a kidney-shaped articular surface which is divided by a horizontal crest into two articulating regions. The upper region articulates with the inferior costal facet on the vertebra above, and the larger region articulates with the superior costal facet on the vertebra with the same number. The transverse process of a thoracic vertebra also articulates at the transverse costal facet with the tubercle of the rib of the same number. The crest gives attachment to the intra-articular ligament.[5]

The neck of the rib is the flattened part that extends laterally from the head. The neck is about 3 cm long. Its anterior surface is flat and smooth, whilst its posterior is perforated by numerous foramina and its surface rough, to give attachment to the ligament of the neck. Its upper border presents a rough crest (crista colli costae) for the attachment of the anterior costotransverse ligament; its lower border is rounded.

On the posterior surface at the neck, is an eminence—the tubercle that consists of an articular and a non-articular portion. The articular portion is the lower and more medial of the two and presents a small, oval surface for articulation with the transverse costal facet on the end of the transverse process of the lower of the two vertebrae to which the head is connected. The non-articular portion is a rough elevation and affords attachment to the ligament of the tubercle. The tubercle is much more prominent in the upper ribs than in the lower ribs.

The angle of a rib (costal angle) may both refer to the bending part of it, and a prominent line in this area, a little in front of the tubercle. This line is directed downward and laterally; this gives attachment to a tendon of the iliocostalis muscle. At this point, the rib is bent in two directions, and at the same time twisted on its long axis.

The distance between the angle and the tubercle is progressively greater from the second to the tenth ribs. The area between the angle and the tubercle is rounded, rough, and irregular, and serves for the attachment of the longissimus dorsi muscle.

Bones

[edit]Ribs and vertebrae

[edit]The first rib (the topmost one) is the most curved and usually the shortest of all the ribs; it is broad and flat, its surfaces looking upward and downward, and its borders inward and outward.

-

First rib seen from above

-

Costal groove position on a central rib

The head is small and rounded, and possesses only a single articular facet, for articulation with the body of the first thoracic vertebra. The neck is narrow and rounded. The tubercle, thick and prominent, is placed on the outer border. It bears a small facet for articulation with the transverse costal facet on the transverse process of T1. There is no angle, but at the tubercle, the rib is slightly bent, with the convexity upward, so that the head of the bone is directed downward. The upper surface of the body is marked by two shallow grooves, separated from each other by a slight ridge prolonged internally into a tubercle, the scalene tubercle, for the attachment of the anterior scalene; the anterior groove transmits the subclavian vein, the posterior the subclavian artery and the lowest trunk of the brachial plexus. Behind the posterior groove is a rough area for the attachment of the medial scalene. The under surface is smooth and without a costal groove. The outer border is convex, thick, and rounded, and at its posterior part gives attachment to the first digitation of the serratus anterior. The inner border is concave, thin, and sharp, and marked about its center by the scalene tubercle. The anterior extremity is larger and thicker than that of any of the other ribs.

The second rib is the second uppermost rib in humans or second most frontal in animals that walk on four limbs. In humans, the second rib is defined as a true rib since it connects with the sternum through the intervention of the costal cartilage anteriorly (at the front). Posteriorly, the second rib is connected with the vertebral column by the second thoracic vertebra. The second rib is much longer than the first rib, but has a very similar curvature. The non-articular portion of the tubercle is occasionally only feebly marked. The angle is slight and situated close to the tubercle. The body is not twisted so that both ends touch any plane surface upon which it may be laid; but there is a bend, with its convexity upward, similar to, though smaller than that found in the first rib. The body is not flattened horizontally like that of the first rib. Its external surface is convex, and looks upward and a little outward; near the middle of it is a rough eminence for the origin of the lower part of the first and the whole of the second digitation of the serratus anterior; behind and above this is attached the posterior scalene. The internal surface, smooth, and concave, is directed downward and a little inward: on its posterior part there is a short costal groove between the ridge of the internal surface of the rib and the inferior border. It protects the intercostal space containing the intercostal veins, intercostal arteries, and intercostal nerves.[6][4]

The ninth rib has a frontal part at the same level as the first lumbar vertebra. This level is called the transpyloric plane, since the pylorus is also at this level.[7]

The tenth rib attaches directly to the body of vertebra T10 instead of between vertebrae like the second through ninth ribs. Due to this direct attachment, vertebra T10 has a complete costal facet on its body.[3]

The eleventh and twelfth ribs, the floating ribs, have a single articular facet on the head, which is of rather large size. They have no necks or tubercles, and are pointed at their anterior ends. The eleventh has a slight angle and a shallow costal groove, whereas the twelfth does not. The twelfth rib is much shorter than the eleventh rib, and only has a one articular facet.[8]

Sternum

[edit]The sternum is a long, flat bone that forms the front of the rib cage. The cartilages of the top seven ribs (the true ribs) join with the sternum at the sternocostal joints. The costal cartilage of the second rib articulates with the sternum at the sternal angle making it easy to locate.[9]

The manubrium is the wider, superior portion of the sternum. The top of the manubrium has a shallow, U-shaped border called the jugular (suprasternal) notch. The clavicular notch is the shallow depression located on either side at the superior-lateral margins of the manubrium. This is the site of the sternoclavicular joint, between the sternum and clavicle. The first ribs also attach to the manubrium.[10]

The transversus thoracis muscle is innervated by one of the intercostal nerves and superiorly attaches at the posterior surface of the lower sternum. Its inferior attachment is the internal surface of costal cartilages two through six and works to depress the ribs.[11]

Development

[edit]Expansion of the rib cage in males is caused by the effects of testosterone during puberty.[12] Thus, males generally have broad shoulders and expanded chests, allowing them to inhale more air to supply their muscles with oxygen.

The development of the rib cage is influenced by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, as well as specific stages of embryonic growth. Genetic factors play a critical role, with specific genes regulating the formation of bones and cartilage to ensure the proper development and alignment of the ribs and sternum. During the embryonic stage, the rib cage begins to form from the mesoderm, one of the three primary germ layers. Ribs develop from structures called somites, which later segment into vertebrae and ribs. Initially, the ribs are composed of cartilage, which gradually ossifies into bone through a process known as endochondral ossification.

As the embryo grows, the ribs elongate and differentiate into three types: true ribs, which attach directly to the sternum; false ribs, which connect to the sternum via cartilage; and floating ribs, which do not attach to the sternum. Additionally, environmental factors such as maternal health, nutrition, and exposure to certain substances can impact rib cage development. For instance, deficiencies in essential nutrients like calcium and vitamin D may hinder proper bone growth and development. Together, these genetic, developmental, and environmental influences ensure the formation of a functional rib cage.

Variation

[edit]Variations in the number of ribs occur. About 1 in 200–500 people have an additional cervical rib, and there is a female predominance.[13] Intrathoracic supernumerary ribs are extremely rare.[14] The rib remnant of the 7th cervical vertebra on one or both sides is occasionally replaced by a free extra rib called a cervical rib, which can mechanically interfere with the nerves (brachial plexus) going to the arm.

In several ethnic groups, most significantly the Japanese, the tenth rib is sometimes a floating rib, as it lacks a cartilaginous connection to the seventh rib.[3]

Function

[edit]

The human rib cage is a component of the human respiratory system. It encloses the thoracic cavity, which contains the lungs. An inhalation is accomplished when the muscular diaphragm, at the floor of the thoracic cavity, contracts and flattens, while the contraction of intercostal muscles lift the rib cage up and out.

Expansion of the thoracic cavity is driven in three planes; the vertical, the anteroposterior and the transverse. The vertical plane is extended by the help of the diaphragm contracting and the abdominal muscles relaxing to accommodate the downward pressure that is supplied to the abdominal viscera by the diaphragm contracting. A greater extension can be achieved by the diaphragm itself moving down, rather than simply the domes flattening. The second plane is the anteroposterior and this is expanded by a movement known as the 'pump handle'. The downward sloping nature of the upper ribs are as such because they enable this to occur. When the external intercostal muscles contract and lift the ribs, the upper ribs are able also to push the sternum up and out. This movement increases the anteroposterior diameter of the thoracic cavity, and hence aids breathing further. The third, transverse, plane is primarily expanded by the lower ribs (some say it is the 7th to 10th ribs in particular), with the diaphragm's central tendon acting as a fixed point. When the diaphragm contracts, the ribs are able to evert (meaning turn outwards or inside out) and produce what is known as the bucket handle movement, facilitated by gliding at the costovertebral joints. In this way, the transverse diameter is expanded and the lungs can fill.

The circumference of the normal adult human rib cage expands by 3 to 5 cm during inhalation.[15]

Clinical significance

[edit]Rib fractures are the most common injury to the rib cage. These most frequently affect the middle ribs. When several adjacent ribs incur two or more fractures each, this can result in a flail chest which is a life-threatening condition.

A dislocated rib can be painful and can be caused simply by coughing, or for example by trauma or lifting heavy weights.[16]

One or more costal cartilages can become inflamed – a condition known as costochondritis; the resulting pain is similar to that of a heart attack.

Abnormalities of the rib cage include pectus excavatum ("sunken chest") and pectus carinatum ("pigeon chest"). A bifid rib is a bifurcated rib, split towards the sternal end, and usually just affecting one of the ribs of a pair. It is a congenital defect affecting about 1.2% of the population. It is often without symptoms though respiratory difficulties and other problems can arise.

Rib removal is the surgical removal of one or more ribs for therapeutic or cosmetic reasons.

Rib resection is the removal of part of a rib.

Regeneration

[edit]The ability of the human rib to regenerate itself has been appreciated for some time.[2][5] However, the repair has only been described in a few case reports. The phenomenon has been appreciated particularly by craniofacial surgeons, who use both cartilage and bone material from the rib for ear, jaw, face, and skull reconstruction.[6][8]

The perichondrium and periosteum are fibrous sheaths of vascular connective tissue surrounding the rib cartilage and bone respectively. These tissues containing a source of progenitor stem cells that drive regeneration.[1][17][18]

Society and culture

[edit]The position of ribs can be permanently altered by a form of body modification called tightlacing, which uses a corset to compress and move the ribs.

The ribs, particularly their sternal ends, are used as a way of estimating age in forensic pathology due to their progressive ossification.[19]

Biblical story

[edit]The number of ribs as 24 (12 pairs) was noted by the Flemish anatomist Vesalius in his key work of anatomy De humani corporis fabrica in 1543, setting off a wave of controversy, as it was traditionally assumed from the Biblical story of Adam and Eve that men's ribs would number one fewer than women's.[20][21] However, thirteenth or "cervical ribs" occur in 1% of humans[12] and this is more common in females than in males.[13]

Other animals

[edit]

In herpetology, costal grooves refer to lateral indents along the integument of salamanders. The grooves run between the axilla to the groin. Each groove overlies the myotomal septa to mark the position of the internal rib.[22][23]

Birds and reptiles have bony uncinate processes on their ribs that project caudally from the vertical section of each rib.[24] These serve to attach sacral muscles and also aid in allowing greater inspiration. Crocodiles have cartilaginous uncinate processes.

Additional images

[edit]-

Anterior surface of sternum and costal cartilages

-

X-ray image of a human chest, with ribs labelled

-

3D model of rib cage

-

Surface projections of the trunk, including each rib, and the costal margin

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ a b "The Thoracic Cage · Anatomy and Physiology". Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ a b Hyman, Libbie Henrietta (1992). Hyman's Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. University of Chicago Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Saladin, Kenneth (2010). Anatomy and Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. p. 485. ISBN 978-0-07-352569-3.

- ^ a b Smith, Sarah (25 June 2015). "Intercostal spaces | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". radiopaedia.org.

- ^ a b "Osteology of the Thorax". TeachMeAnatomy. 2013-05-02. Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2024-05-28.

- ^ a b Moore, Dalley & Agur. 2009. Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 6th Edition. 90 Pp. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, ISBN 0-7817-7525-6, ISBN 978-0-7817-7525-0

- ^ Bålens ytanatomi (surface anatomy). Godfried Roomans, Mats Hjortberg and Anca Dragomir. Institution for Anatomy, Uppsala. 2008.

- ^ a b Jung, Jaewoong; Lee, Misoon; Choi, Dasom (2020-09-04). "Twelfth rib syndrome: a case report". The Journal of International Medical Research. 48 (9) 0300060520952651. doi:10.1177/0300060520952651. ISSN 0300-0605. PMC 7479855. PMID 32883133.

- ^ Agur, Anne M.R.; Dalley, Arthur F. II (2009). Grant's Atlas of Anatomy, Twelfth Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7817-7055-2.

- ^

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (May 14, 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 7.4 The Thoracic Cage. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Betts, J Gordon; Desaix, Peter; Johnson, Eddie; Johnson, Jody E; Korol, Oksana; Kruse, Dean; Poe, Brandon; Wise, James; Womble, Mark D; Young, Kelly A (May 14, 2023). Anatomy & Physiology. Houston: OpenStax CNX. 7.4 The Thoracic Cage. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3.

- ^ Agur, Anne M.R.; Dalley, Arthur F. II (2009). Grant's Atlas of Anatomy, Twelfth Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7817-7055-2.

- ^ a b Testosterone causes expansion of rib cage during puberty as one of secondary sex characteristics."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-09-11. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Kurihara Y; Yakushiji YK; Matsumoto J; Ishikawa T; Hirata K (Jan–Feb 1999). "The Ribs: Anatomic and Radiologic Considerations" (PDF). RadioGraphics. 19 (1). Radiological Society of North America: 105–119. doi:10.1148/radiographics.19.1.g99ja02105. ISSN 1527-1323. PMID 9925395. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ Kamano H; Ishihama T; Ishihama H; Kubota Y; Tanaka T; Satoh K (June 1, 2006). "Bifid intrathoracic rib: a case report and classification of intrathoracic ribs". Internal Medicine. 45 (9). The Japanese Society of Internal Medicine: 627–630. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1502. PMID 16755094.

- ^ Respiratory system examination Archived 2012-03-23 at the Wayback Machine citing: Health & Physical Assessment, Mosby-Year Book, inc. School of Nursing, Peking University, 2003

- ^ "Anatomy of the Human ribs - Dislocated Rib". Dislocated Rib. 2 February 2016. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016.

- ^ Srour, MK; Fogel, Jl; Yamaguchi, KT; Montgomery, AP; Izuhara, AK; Misakian, AL; Lam, S; Lakeland, DL; Urata, MM; Lee, JS; Mariani, FV (2015). "Natural large-scale regeneration of rib cartilage in a mouse model". JBMR. 30 (2): 297–308. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2326. PMC 8253918. PMID 25142306.

- ^ Kuwahara, ST; Serowoky, MA; Vakhshori, V; Tripuraneni, N; Hegde, NV; Lieberman, JR; Crump, JG; Mariani, FV (2019). "Sox9+ messenger cells orchestrate large-scale skeletal regeneration in the mammalian rib". eLife. 8. doi:10.7554/eLife.40715. PMC 6464605. PMID 30983567.

- ^ Franklin, D (Jan 2010). "Forensic age estimation in human skeletal remains: current concepts and future directions". Legal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 12 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.09.001. PMID 19853490.

- ^ "Chapter 19 On the Bones of the Thorax". Archived from the original on 2007-07-06. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ Dresden, Danielle (2020-03-12). "How many ribs do humans have? Men, women, and anatomy". Medical News Today. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

Although many people might think that males have fewer ribs than females—most likely sparked by the biblical story of Adam and Eve—there is no factual evidence.

- ^ Duellman, W.E., Trueb, L. (1986). Biology of Amphibians. 670 Pp. McGraw - Hill Book Company, New York, New York, ISBN 0-8018-4780-X, 9780801847806

- ^ J. W. Petranka. 1998. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. 587 Pp. Smithsonian Institution Press, ISBN 1-56098-828-2, ISBN 978-1-56098-828-1

- ^ Kardong, Kenneth V. (1995). Vertebrates: comparative anatomy, function, evolution. McGraw-Hill. pp. 55, 57. ISBN 0-697-21991-7.

References

[edit]- Orientation of the intercostal muscle fibers in the human rib cage, Subit D., Glacet A., Hamzah M., Crandall J., Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering, 2015, 18, pp. 2064–2065

- Clinically Oriented Anatomy, 4th ed. Keith L. Moore and Robert F. Dalley. pp. 62–64

- Principles of Anatomy Physiology, Tortora GJ and Derrickson B. 11th ED. John Wiley and Sons, 2006. ISBN 0-471-68934-3

- De Humani Corporis Fabrica: online English translation of Vesalius' books on human anatomy.