Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vertebra

View on Wikipedia| Vertebra | |

|---|---|

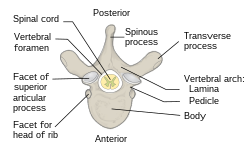

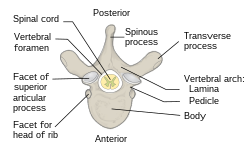

A typical vertebra, superior view | |

A section of the human vertebral column, showing multiple vertebrae in a left posterolateral view. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Spinal column |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vertebra |

| TA98 | A02.2.01.001 |

| TA2 | 1011 |

| FMA | 9914 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

Each vertebra (pl.: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal segment and the particular species.

The basic configuration of a vertebra varies; the vertebral body (also centrum) is of bone and bears the load of the vertebral column. The upper and lower surfaces of the vertebra body give attachment to the intervertebral discs. The posterior part of a vertebra forms a vertebral arch, in eleven parts, consisting of two pedicles (pedicle of vertebral arch), two laminae, and seven processes. The laminae give attachment to the ligamenta flava (ligaments of the spine). There are vertebral notches formed from the shape of the pedicles, which form the intervertebral foramina when the vertebrae articulate. These foramina are the entry and exit conduits for the spinal nerves. The body of the vertebra and the vertebral arch form the vertebral foramen; the larger, central opening that accommodates the spinal canal, which encloses and protects the spinal cord.

Vertebrae articulate with each other to give strength and flexibility to the spinal column and the shape at their back and front aspects determines the range of movement. Structurally, vertebrae are essentially alike across the vertebrate species, with the greatest difference seen between an aquatic animal and other vertebrate animals. As such, vertebrates take their name from the vertebrae that compose the vertebral column.

Structure

[edit]In the human vertebral column, the size of the vertebrae varies according to placement in the vertebral column, spinal loading, posture and pathology. Along the length of the spine, the vertebrae change to accommodate different needs related to stress and mobility.[1] Each vertebra is an irregular bone.

A typical vertebra has a body (vertebral body), also known as the centrum, which consists of a large anterior middle portion, and a posterior vertebral arch,[2] also called a neural arch.[3] The body is composed of cancellous bone, which is the spongy type of osseous tissue, whose microanatomy has been specifically studied within the pedicle bones.[4] This cancellous bone is in turn, covered by a thin coating of cortical bone (or compact bone), the hard and dense type of osseous tissue. The vertebral arch and processes have thicker coverings of cortical bone. The upper and lower surfaces of the body of the vertebra are flattened and rough in order to give attachment to the intervertebral discs. These surfaces are the vertebral endplates which are in direct contact with the intervertebral discs and form the joint. The endplates are formed from a thickened layer of the cancellous bone of the vertebral body, the top layer being more dense. The endplates function to contain the adjacent discs, to evenly spread the applied loads, and to provide anchorage for the collagen fibers of the disc. They also act as a semi-permeable interface for the exchange of water and solutes.[5]

The vertebral arch is formed by pedicles and laminae. Two pedicles extend from the sides of the vertebral body to join the body to the arch. The pedicles are short thick processes that extend, one from each side, posteriorly, from the junctions of the posteriolateral surfaces of the centrum, on its upper surface. From each pedicle a broad plate, a lamina, projects backward and medially to join and complete the vertebral arch and form the posterior border of the vertebral foramen, which completes the triangle of the vertebral foramen.[6] The upper surfaces of the laminae are rough to give attachment to the ligamenta flava. These ligaments connect the laminae of adjacent vertebra along the length of the spine from the level of the second cervical vertebra. Above and below the pedicles are shallow depressions called vertebral notches (superior and inferior). When the vertebrae articulate the notches align with those on adjacent vertebrae and these form the openings of the intervertebral foramina. The foramina allow the entry and exit of the spinal nerves from each vertebra, together with associated blood vessels. The articulating vertebrae provide a strong pillar of support for the body.

Processes

[edit]There are seven processes projecting from the vertebra:

- one spinous process

- two transverse processes

- four articular processes

A major part of a vertebra is a backward extending spinous process (sometimes called the neural spine) which projects centrally.[7] This process points dorsally and caudally from the junction of the laminae.[7] The spinous process serves to attach muscles and ligaments.

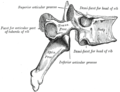

The two transverse processes, one on each side of the vertebral body, project laterally from either side at the point where the lamina joins the pedicle, between the superior and inferior articular processes.[7] They also serve for the attachment of muscles and ligaments, in particular the intertransverse ligaments. There is a facet on each of the transverse processes of thoracic vertebrae which articulates with the tubercle of the rib.[8] A facet on each side of the thoracic vertebral body articulates with the head of the rib. The transverse process of a lumbar vertebra is also sometimes called the costal[9][10] or costiform process[11] because it corresponds to a rudimentary rib (costa) which, as opposed to the thorax, is not developed in the lumbar region.[11][12]

There are superior and inferior articular facet joints on each side of the vertebra, which serve to restrict the range of movement possible. These facets are joined by a thin portion of the vertebral arch called the pars interarticularis.

Regional variation

[edit]

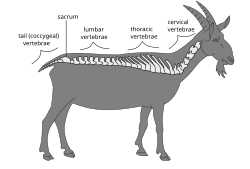

Vertebrae take their names from the regions of the vertebral column that they occupy. There are usually thirty-three vertebrae in the human vertebral column — seven cervical vertebrae, twelve thoracic vertebrae, five lumbar vertebrae, five fused sacral vertebrae forming the sacrum and four coccygeal vertebrae, forming the coccyx. Excluding rare deviations, the total number of vertebrae ranges from 32 to 35.[13] In about 10% of people, both the total number of pre-sacral vertebrae and the number of vertebrae in individual parts of the spine can vary.[14][15] The most frequent deviations are eleven (rarely thirteen) thoracic vertebrae, four or six lumbar vertebrae and three or five coccygeal vertebrae (rarely up to seven).[15]

The regional vertebrae increase in size as they progress downward but become smaller in the coccyx.

Cervical

[edit]

There are seven cervical vertebrae (but eight cervical spinal nerves), designated C1 through C7. These bones are, in general, small and delicate. Their spinous processes are short (with the exception of C2 and C7, which have palpable spinous processes). C1 is also called the atlas, and C2 is also called the axis. The structure of these vertebrae is the reason why the neck and head have a large range of motion. The atlanto-occipital joint allows the skull to move up and down, while the atlanto-axial joint allows the upper neck to twist left and right. The axis also sits upon the first intervertebral disc of the spinal column.

Cervical vertebrae possess transverse foramina to allow for the vertebral arteries to pass through on their way to the foramen magnum to end in the circle of Willis. These are the smallest, lightest vertebrae and the vertebral foramina are triangular in shape. The spinous processes are short and often bifurcated (the spinous process of C7 is not bifurcated, and is substantially longer than that of the other cervical spinous processes).[16]

The atlas differs from the other vertebrae in that it has no body and no spinous process. It has instead a ring-like form, having an anterior and a posterior arch and two lateral masses. At the outside centre points of both arches there is a tubercle, an anterior tubercle and a posterior tubercle, for the attachment of muscles. The front surface of the anterior arch is convex and its anterior tubercle gives attachment to the longus colli muscle. The posterior tubercle is a rudimentary spinous process and gives attachment to the rectus capitis posterior minor muscle. The spinous process is small so as not to interfere with the movement between the atlas and the skull. On the under surface is a facet for articulation with the dens of the axis.

Specific to the cervical vertebra is the transverse foramen (also known as foramen transversarium). This is an opening on each of the transverse processes which gives passage to the vertebral artery and vein and a sympathetic nerve plexus. On the cervical vertebrae other than the atlas, the anterior and posterior tubercles are on either side of the transverse foramen on each transverse process. The anterior tubercle on the sixth cervical vertebra is called the carotid tubercle because it separates the carotid artery from the vertebral artery.

There is a hook-shaped uncinate process on the side edges of the top surface of the bodies of the third to the seventh cervical vertebrae and of the first thoracic vertebra. Together with the vertebral disc, this uncinate process prevents a vertebra from sliding backward off the vertebra below it and limits lateral flexion (side-bending). Luschka's joints involve the vertebral uncinate processes.

The spinous process on C7 is distinctively long and gives the name vertebra prominens to this vertebra. Also a cervical rib can develop from C7 as an anatomical variation.

The term cervicothoracic is often used to refer to the cervical and thoracic vertebrae together, and sometimes also their surrounding areas.

Thoracic

[edit]

The twelve thoracic vertebrae and their transverse processes have surfaces that articulate with the ribs. Some rotation can occur between the thoracic vertebrae, but their connection with the rib cage prevents much flexion or other movement. They may also be known as "dorsal vertebrae" in the human context.

The vertebral bodies are roughly heart-shaped and are about as wide anterio-posteriorly as they are in the transverse dimension. Vertebral foramina are roughly circular in shape.

The top surface of the first thoracic vertebra has a hook-shaped uncinate process, just like the cervical vertebrae.

The thoracolumbar spine or thoracolumbar division refers to the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae together, and sometimes also their surrounding areas.

The thoracic vertebrae attach to ribs and so have articular facets specific to them; these are the superior, transverse and inferior costal facets. As the vertebrae progress down the spine they increase in size to match up with the adjoining lumbar section.

Lumbar

[edit]

The five lumbar vertebrae are the largest of the vertebrae, their robust construction being necessary for supporting greater weight than the other vertebrae. They allow significant flexion, extension and moderate lateral flexion (side-bending). The discs between these vertebrae create a natural lumbar lordosis (a spinal curvature that is concave posteriorly).[citation needed] This is due to the difference in thickness between the front and back parts of the intervertebral discs.

The lumbar vertebrae are located between the ribcage and the pelvis and are the largest of the vertebrae. The pedicles are strong, as are the laminae, and the spinous process is thick and broad. The vertebral foramen is large and triangular. The transverse processes are long and narrow and three tubercles can be seen on them. These are a lateral costiform process, a mammillary process and an accessory process.[17] The superior, or upper tubercle is the mammillary process which connects with the superior articular process. The multifidus muscle attaches to the mammillary process and this muscle extends through the length of the vertebral column, giving support. The inferior, or lower tubercle is the accessory process and this is found at the back part of the base of the transverse process. The term lumbosacral is often used to refer to the lumbar and sacral vertebrae together, and sometimes includes their surrounding areas.

Sacral

[edit]

There are five sacral vertebrae (S1–S5) which are fused in maturity, into one large bone, the sacrum, with no intervertebral discs.[18] The sacrum with the ilium forms a sacroiliac joint on each side of the pelvis, which articulates with the hips.

Coccygeal

[edit]The last three to five coccygeal vertebrae (but usually four) (Co1–Co5) make up the tailbone or coccyx.[19] There are no intervertebral discs.

Development

[edit]

Somites form in the early embryo and some of these develop into sclerotomes. The sclerotomes form the vertebrae as well as the rib cartilage and part of the occipital bone. From their initial location within the somite, the sclerotome cells migrate medially toward the notochord. These cells meet the sclerotome cells from the other side of the paraxial mesoderm. The lower half of one sclerotome fuses with the upper half of the adjacent one to form each vertebral body.[20] From this vertebral body, sclerotome cells move dorsally and surround the developing spinal cord, forming the vertebral arch. Other cells move distally to the costal processes of thoracic vertebrae to form the ribs.[20]

Function

[edit]Functions of vertebrae include:

- Support of the vertebrae function in the skeletomuscular system by forming the vertebral column to support the body

- Protection. Vertebrae contain a vertebral foramen for the passage of the spinal canal and its enclosed spinal cord and covering meninges. They also afford sturdy protection for the spinal cord. The upper and lower surfaces of the centrum are flattened and rough in order to give attachment to the intervertebral discs.

- Movement. The vertebrae also provide the openings, the intervertebral foramina which allow the entry and exit of the spinal nerves. Similarly to the surfaces of the centrum, the upper and lower surfaces of the fronts of the laminae are flattened and rough to give attachment to the ligamenta flava. Working together in the vertebral column their sections provide controlled movement and flexibility.

- Feeding of the intervertebral discs through the reflex (hyaline ligament) plate that separates the cancellous bone of the vertebral body from each disk

-

The spinal cord nested in the vertebral column.

-

Vertebral joint

-

A facet joint between the superior and inferior articular processes (labeled at top and bottom).

Clinical significance

[edit]There are a number of congenital vertebral anomalies, mostly involving variations in the shape or number of vertebrae, and many of which are unproblematic. Others though can cause compression of the spinal cord. Wedge-shaped vertebrae, called hemivertebrae can cause an angle to form in the spine which can result in the spinal curvature diseases of kyphosis, scoliosis and lordosis. Severe cases can cause spinal cord compression. Block vertebrae where some vertebrae have become fused can cause problems. Spina bifida can result from the incomplete formation of the vertebral arch.

Spondylolysis is a defect in the pars interarticularis of the vertebral arch. In most cases this occurs in the lowest of the lumbar vertebrae (L5), but may also occur in the other lumbar vertebrae, as well as in the thoracic vertebrae.

Spinal disc herniation, more commonly called a slipped disc, is the result of a tear in the outer ring (anulus fibrosus) of the intervertebral disc, which lets some of the soft gel-like material, the nucleus pulposus, bulge out in a hernia. This may be treated by a minimally-invasive endoscopic procedure called Tessys method.

A laminectomy is a surgical operation to remove the laminae in order to access the spinal canal.[21] The removal of just part of a lamina is called a laminotomy.

A pinched nerve caused by pressure from a disc, vertebra or scar tissue might be remedied by a foraminotomy to broaden the intervertebral foramina and relieve pressure. It can also be caused by a foramina stenosis, a narrowing of the nerve opening, as a result of arthritis.

Another condition is spondylolisthesis when one vertebra slips forward onto another. The reverse of this condition is retrolisthesis where one vertebra slips backward onto another.

The vertebral pedicle is often used as a radiographic marker and entry point in vertebroplasty, kyphoplasty, and spinal fusion procedures.

The arcuate foramen is a common anatomical variation more frequently seen in females. It is a bony bridge found on the first cervical vertebra, the atlas where it covers the groove for the vertebral artery.[22]

Degenerative disc disease is a condition usually associated with ageing in which one or more discs degenerate. This can often be a painfree condition but can also be very painful.

Other animals

[edit]

In other animals, the vertebrae take the same regional names except for the coccygeal – in animals with tails, the separate vertebrae are usually called the caudal vertebrae.[19] Because of the different types of locomotion and support needed between the aquatic and other vertebrates, the vertebrae between them show the most variation, though basic features are shared. The spinous processes which are backward extending are directed upward in animals without an erect stance. These processes can be very large in the larger animals since they attach to the muscles and ligaments of the body. In the elephant, the vertebrae are connected by tight joints, which limit the backbone's flexibility. Spinous processes are exaggerated in some animals, such as the extinct Dimetrodon and Spinosaurus, where they form a sailback or finback.

Vertebrae with saddle-shaped articular surfaces on their bodies, called "heterocoelous", allow vertebrae to flex both vertically and horizontally while preventing twisting motions. Such vertebrae are found in the necks of birds and some turtles.[23]

"Procoelous" vertebrae feature a spherical protrusion extending from the caudal end of the centrum of one vertebra that fits into a concave socket on the cranial end of the centrum of an adjacent vertebra.[24] These vertebrae are most often found in reptiles,[25][26] but are found in some amphibians such as frogs.[27] The vertebrae fit together in a ball-and-socket articulation, in which the convex articular feature of an anterior vertebra acts as the ball to the socket of a caudal vertebra.[25] This type of connection permits a wide range of motion in most directions, while still protecting the underlying nerve cord. The central point of rotation is located at the midline of each centrum, and therefore flexion of the muscle surrounding the vertebral column does not lead to an opening between vertebrae.[27]

In many species, though not in mammals, the cervical vertebrae bear ribs. In many groups, such as lizards and saurischian dinosaurs, the cervical ribs are large; in birds, they are small and completely fused to the vertebrae. The transverse processes of mammals are homologous to the cervical ribs of other amniotes. In the whale, the cervical vertebrae are typically fused, an adaptation trading flexibility for stability during swimming.[28][29] All mammals except manatees and sloths have seven cervical vertebrae, whatever the length of the neck.[30] This includes seemingly unlikely animals such as the giraffe, the camel, and the blue whale, for example. Birds usually have more cervical vertebrae with most having a highly flexible neck consisting of 13–25 vertebrae.

In all mammals, the thoracic vertebrae are connected to ribs and their bodies differ from the other regional vertebrae due to the presence of facets. Each vertebra has a facet on each side of the vertebral body, which articulates with the head of a rib. There is also a facet on each of the transverse processes which articulates with the tubercle of a rib. The number of thoracic vertebrae varies considerably across the species.[31] Most marsupials have thirteen, but koalas only have eleven.[32] The usual number is twelve to fifteen in mammals, (twelve in the human), though there are from eighteen to twenty in the horse, tapir, rhinoceros and elephant. In certain sloths, there is an extreme number of twenty-five and at the other end only nine in the cetacean.[33]

There are fewer lumbar vertebrae in chimpanzees and gorillas, which have three in contrast to the five in the genus Homo. This reduction in number gives an inability of the lumbar spine to lordose but gives an anatomy that favours vertical climbing, and hanging ability more suited to feeding locations in high-canopied regions.[34] The bonobo differs by having four lumbar vertebrae.

Caudal vertebrae are the bones that make up the tails of vertebrates.[35] They range in number from a few to fifty, depending on the length of the animal's tail. In humans and other tailless primates, they are called the coccygeal vertebrae, number from three to five and are fused into the coccyx.[36]

Additional images

[edit]-

Vertebral arches of three thoracic vertebrae

-

Costovertebral joints seen from the front

-

Lower thoracic and upper lumbar vertebrae seen from the side

-

Cervical vertebrae seen from the back

-

Vertebrae anatomy

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 96 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 96 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ McGraw-Hill Science and Technology[full citation needed]

- ^ O'Rahilly, Ronan. Swenson, Rand; Müller, Fabiola; Carpenter, Stanley (eds.). "Chapter 39: The vertebral column". Basic Human Anatomy. Dartmouth College.

- ^ Dorland's (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 329. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ Gdyczynski, C.M.; Manbachi, A.; et al. (2014). "On estimating the directionality distribution in pedicle trabecular bone from micro-CT images". Physiological Measurement. 35 (12): 2415–2428. Bibcode:2014PhyM...35.2415G. doi:10.1088/0967-3334/35/12/2415. PMID 25391037. S2CID 206078730.

- ^ Muller-Gerbl, M; et al. (Mar 2008). "The distribution of mineral density in the cervical vertebral endplates". Eur Spine J. 17 (3): 432–438. doi:10.1007/s00586-008-0601-5. PMC 2270387. PMID 18193299.

- ^ Taylor, Tim. "Lumbar Vertebrae". InnerBody. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ a b c Cramer, Gregory D. (2014). "General Characteristics of the Spine". Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans. pp. 15–64. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-07954-9.00002-5. ISBN 978-0-323-07954-9.

- ^ Standring, Susan (2008). "Thoracic vertebrae". Gray's Anatomy. p. 746.

- ^ Platzer (2004), pp 42–43

- ^ Latin costa refers to either a "rib" or "side" of the body. (Diab (1999), p 76)

- ^ a b Tweedie, A. The library of medicine p. 31

- ^ Heinz Feneis, Wolfgang Dauber (2000) Pocket Atlas of Human Anatomy: Based on the International Nomenclature p. 2

- ^ Watson, Charles; Kayalioglu, Gulgun (2009). "The Organization of the Spinal Cord". The Spinal Cord. pp. 1–7. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-374247-6.50005-5. ISBN 978-0-12-374247-6.

- ^ Hu, Zongshan; Zhang, Zhen; Zhao, Zhihui; Zhu, Zezhang; Liu, Zhen; Qiu, Yong (August 2016). "A neglected point in surgical treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Variations in the number of vertebrae". Medicine. 95 (34) e4682. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000004682. PMC 5400342. PMID 27559975.

- ^ a b Ying-zhao, Yan; et al. (February 2022). "Variation in Global Spinal Sagittal Parameters in Asymptomatic Adults with 11 Thoracic Vertebrae, four Lumbar Vertebrae, and six Lumbar Vertebrae". Orthopaedic Surgery. 14 (2). John Wiley & Sons: 341–348. doi:10.1111/os.13185. PMC 8867438. PMID 34935276.

- ^ Cramer, Gregory D. (2014). "The Cervical Region". Clinical Anatomy of the Spine, Spinal Cord, and Ans. pp. 135–209. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-07954-9.00005-0. ISBN 978-0-323-07954-9.

- ^ Postacchini, Franco (1999) Lumbar Disc Herniation p. 19

- ^ Drake et al, Gray's Anatomy for Students, Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier (2010), 2nd edition, chapter 2

- ^ a b Weisberger, Mindy (March 23, 2024). "Why don't humans have tails? Scientists find answers in an unlikely place". CNN. Archived from the original on March 24, 2024. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ a b Walker, Warren F., Jr. (1987) Functional Anatomy of the Vertebrate San Francisco: Saunders College Publishing.

- ^ Dorland's (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 1003. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ Cakmak, O; et al. (Sep 2005). "Arcuate foramen its clinical significance". Saudi Med J. 26 (9): 1409–13. PMID 16155658.

- ^ Kardong, Kenneth V. (2002). Vertebrates: comparative anatomy, function, evolution. McGraw-Hill. pp. 288–289. ISBN 978-0-07-290956-2.

- ^ Romer, Alfred (1962). The Vertebrate Body (3 ed.). Philadelphia, Pa; London, W.C.I.: W.B. Saunders Company.

- ^ a b Parker, W. K. (1881). "Abstract Of Lectures On The Structure Of The Skeleton In The Sauropsida". The British Medical Journal. 1 (1053): 329–330. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1053.329. JSTOR 25256369. PMC 2263429.

- ^ Romer, Alfred (1956). Osteology of the Reptiles. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company. pp. 0–89464–985–X.

- ^ a b Kardong, Kenneth V. (2015). Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution (7 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-802302-6.

- ^ "Beluga Whale". Yellowmagpie.com. 2012-06-27. Retrieved 2012-08-12.

- ^ "About Whales". Whalesalive.org.au. 2009-06-26. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- ^ Dierauf, Leslie; Gulland, Frances M. D. (June 27, 2001). CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine: Health, Disease, and Rehabilitation, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-4163-7. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ^ Hyman, Libbie (1922). Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 123.

- ^ "Physical Characteristics of the Koala". Australian Koala Foundation. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ Hyman (1922), p. 124

- ^ Lovejoy, C.O and McCullum, M.A. (2010). "Spinopelvic pathways to bipedality:why no hominids ever relied on a bent-hip-bent-knee gait". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 365 (1556): 3289–99. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0112. PMC 2981964. PMID 20855303.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kardong, Kenneth V. (2002). Vertebrates: comparative anatomy, function, evolution. McGraw-Hill. pp. 287–288. ISBN 978-0-07-290956-2.

- ^ Hyman, Libbie (1922). Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 125.

External links

[edit]- Atlas image: back_bone13 at the University of Michigan Health System – Axis & Atlas Articulated, Posterior View

- Anatomy image: skel/atlas2 at Human Anatomy Lecture (Biology 129), Pennsylvania State University

- Anatomy photo:26:os-0110 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Anatomy figure: 02:01-10 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Anatomy figure: 18:02-01 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Vertebra[permanent dead link] - BlueLink Anatomy - University of Michigan Medical School

- Atlas image: back_bone28 at the University of Michigan Health System

- Anatomy figure: 02:02-08 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- The shapes of the articulating ends of vertebrae Archived 2015-05-03 at the Wayback Machine – University of the Cumberlands