Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Equiangular polygon

View on Wikipedia| Direct | Indirect | Skew |

|---|---|---|

A rectangle, ⟨4⟩, is a convex direct equiangular polygon, containing four 90° internal angles. |

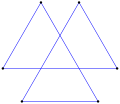

A concave indirect equiangular polygon, ⟨6-2⟩, like this hexagon, counterclockwise, has five left turns and one right turn, like this tetromino. |

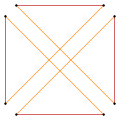

A skew polygon has equal angles off a plane, like this skew octagon alternating red and blue edges on a cube. |

| Direct | Indirect | Counter-turned |

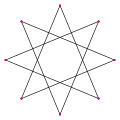

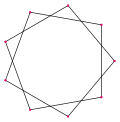

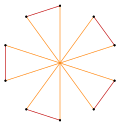

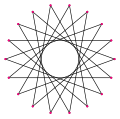

A multi-turning equiangular polygon can be direct, like this octagon, ⟨8/2⟩, has 8 90° turns, totaling 720°. |

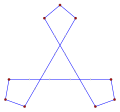

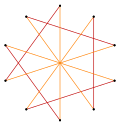

A concave indirect equiangular polygon, ⟨5-2⟩, counterclockwise has 4 left turns and one right turn. (-1.2.4.3.2)60° |

An indirect equiangular hexagon, ⟨6-6⟩90° with 3 left turns, 3 right turns, totaling 0°. |

In Euclidean geometry, an equiangular polygon is a polygon whose vertex angles are equal. If the lengths of the sides are also equal (that is, if it is also equilateral) then it is a regular polygon. Isogonal polygons are equiangular polygons which alternate two edge lengths.

For clarity, a planar equiangular polygon can be called direct or indirect. A direct equiangular polygon has all angles turning in the same direction in a plane and can include multiple turns. Convex equiangular polygons are always direct. An indirect equiangular polygon can include angles turning right or left in any combination. A skew equiangular polygon may be isogonal, but can't be considered direct since it is nonplanar.

A spirolateral nθ is a special case of an equiangular polygon with a set of n integer edge lengths repeating sequence until returning to the start, with vertex internal angles θ.

Construction

[edit]An equiangular polygon can be constructed from a regular polygon or regular star polygon where edges are extended as infinite lines. Each edges can be independently moved perpendicular to the line's direction. Vertices represent the intersection point between pairs of neighboring line. Each moved line adjusts its edge-length and the lengths of its two neighboring edges.[1] If edges are reduced to zero length, the polygon becomes degenerate, or if reduced to negative lengths, this will reverse the internal and external angles.

For an even-sided direct equiangular polygon, with internal angles θ°, moving alternate edges can invert all vertices into supplementary angles, 180-θ°. Odd-sided direct equiangular polygons can only be partially inverted, leaving a mixture of supplementary angles.

Every equiangular polygon can be adjusted in proportions by this construction and still preserve equiangular status.

This convex direct equiangular hexagon, ⟨6⟩, is bounded by 6 lines with 60° angle between. Each line can be moved perpendicular to its direction. |

This concave indirect equiangular hexagon, ⟨6-2⟩, is also bounded by 6 lines with 90° angle between, each line moved independently, moving vertices as new intersections. |

Equiangular polygon theorem

[edit]For a convex equiangular p-gon, each internal angle is 180(1−2/p)°; this is the equiangular polygon theorem.

For a direct equiangular p/q star polygon, density q, each internal angle is 180(1−2q/p)°, with 1 < 2q < p. For w = gcd(p,q) > 1, this represents a w-wound p/w/q/w star polygon, which is degenerate for the regular case.

A concave indirect equiangular (pr+pl)-gon, with pr right turn vertices and pl left turn vertices, will have internal angles of 180(1−2/|pr−pl|))°, regardless of their sequence. An indirect star equiangular (pr+pl)-gon, with pr right turn vertices and pl left turn vertices and q total turns, will have internal angles of 180(1−2q/|pr−pl|))°, regardless of their sequence. An equiangular polygon with the same number of right and left turns has zero total turns, and has no constraints on its angles.

Notation

[edit]Every direct equiangular p-gon can be given a notation ⟨p⟩ or ⟨p/q⟩, like regular polygons {p} and regular star polygons {p/q}, containing p vertices, and stars having density q.

Convex equiangular p-gons ⟨p⟩ have internal angles 180(1−2/p)°, while direct star equiangular polygons, ⟨p/q⟩, have internal angles 180(1−2q/p)°.

A concave indirect equiangular p-gon can be given the notation ⟨p−2c⟩, with c counter-turn vertices. For example, ⟨6−2⟩ is a hexagon with 90° internal angles of the difference, ⟨4⟩, 1 counter-turned vertex. A multiturn indirect equilateral p-gon can be given the notation ⟨p−2c/q⟩ with c counter turn vertices, and q total turns. An equiangular polygon <p−p> is a p-gon with undefined internal angles θ, but can be expressed explicitly as ⟨p−p⟩θ.

Other properties

[edit]Viviani's theorem holds for equiangular polygons:[2]

- The sum of distances from an interior point to the sides of an equiangular polygon does not depend on the location of the point, and is that polygon's invariant.

A cyclic polygon is equiangular if and only if the alternate sides are equal (that is, sides 1, 3, 5, ... are equal and sides 2, 4, ... are equal). Thus if n is odd, a cyclic polygon is equiangular if and only if it is regular.[3]

For prime p, every integer-sided equiangular p-gon is regular. Moreover, every integer-sided equiangular pk-gon has p-fold rotational symmetry.[4]

An ordered set of side lengths gives rise to an equiangular n-gon if and only if either of two equivalent conditions holds for the polynomial it equals zero at the complex value it is divisible by [5]

Direct equiangular polygons by sides

[edit]Direct equiangular polygons can be regular, isogonal, or lower symmetries. Examples for <p/q> are grouped into sections by p and subgrouped by density q.

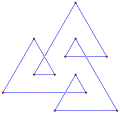

Equiangular triangles

[edit]Equiangular triangles must be convex and have 60° internal angles. It is an equilateral triangle and a regular triangle, ⟨3⟩={3}. The only degree of freedom is edge-length.

-

Regular, {3}, r6

Equiangular quadrilaterals

[edit]

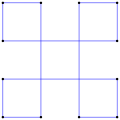

Direct equiangular quadrilaterals have 90° internal angles. The only equiangular quadrilaterals are rectangles, ⟨4⟩, and squares, {4}.

An equiangular quadrilateral with integer side lengths may be tiled by unit squares.[6]

-

Regular, {4}, r8

-

Spirolateral 290°, p4

Equiangular pentagons

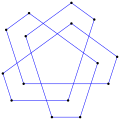

[edit]Direct equiangular pentagons, ⟨5⟩ and ⟨5/2⟩, have 108° and 36° internal angles respectively.

- 108° internal angle from an equiangular pentagon, ⟨5⟩

Equiangular pentagons can be regular, have bilateral symmetry, or no symmetry.

-

Regular, r10

-

Bilateral symmetry, i2

-

No symmetry, a1

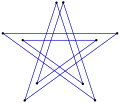

- 36° internal angles from an equiangular pentagram, ⟨5/2⟩

-

Regular pentagram, r10

-

Irregular, d2

Equiangular hexagons

[edit]

Direct equiangular hexagons, ⟨6⟩ and ⟨6/2⟩, have 120° and 60° internal angles respectively.

- 120° internal angles of an equiangular hexagon, ⟨6⟩

An equiangular hexagon with integer side lengths may be tiled by unit equilateral triangles.[6]

-

Regular, {6}, r12

-

Spirolateral (1,2)120°, p6

-

Spirolateral (1…3)120°, g2

-

Spirolateral (1,2,2)120°, i4

-

Spirolateral (1,2,2,2,1,3)120°, p2

- 60° internal angles of an equiangular double-wound triangle, ⟨6/2⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r6

-

Spirolateral (1,3)60°, p6

-

Spirolateral (1,2)60°, p6

-

Spirolateral (2,3)60°, p6

-

Spirolateral (1,2,3,4,3,2)60°, p2

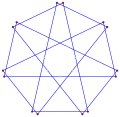

Equiangular heptagons

[edit]Direct equiangular heptagons, ⟨7⟩, ⟨7/2⟩, and ⟨7/3⟩ have 128 4/7°, 77 1/7° and 25 5/7° internal angles respectively.

- 128.57° internal angles of an equiangular heptagon, ⟨7⟩

-

Regular, {7}, r14

-

Irregular, i2

- 77.14° internal angles of an equiangular heptagram, ⟨7/2⟩

-

Regular, r14

-

Irregular, i2

- 25.71° internal angles of an equiangular heptagram, ⟨7/3⟩

-

Regular, r14

-

Irregular, i2

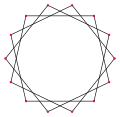

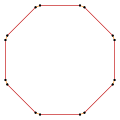

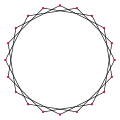

Equiangular octagons

[edit]Direct equiangular octagons, ⟨8⟩, ⟨8/2⟩ and ⟨8/3⟩, have 135°, 90° and 45° internal angles respectively.

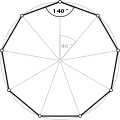

- 135° internal angles from an equiangular octagon, ⟨8⟩

-

Regular, r16

-

Spirolateral (1,2)135°, p8

-

Spirolateral (1…4)135°, g2

-

Unequal truncated square, p2

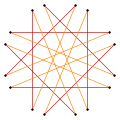

- 90° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound square, ⟨8/2⟩

-

Regular degenerate, r8

-

Spirolateral (1,2,2,3,3,2,2,1)90°, d2

-

Spirolateral (2,1,3,2,2,3,1,2)90°, d2

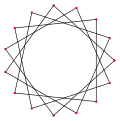

- 45° internal angles from an equiangular octagram, ⟨8/3⟩

-

Regular, r16

-

Isogonal, p8

-

Isogonal, p8

-

Spirolateral, (1,2)45°, p8

-

Isogonal, p8

-

Spirolateral (1…4)45°, g2

Equiangular enneagons

[edit]Direct equiangular enneagons, ⟨9⟩, ⟨9/2⟩, ⟨9/3⟩, and ⟨9/4⟩ have 140°, 100°, 60° and 20° internal angles respectively.

- 140° internal angles from an equiangular enneagon ⟨9⟩

-

Regular, r18

-

Spirolateral (1,1,3)140°, i6

- 100° internal angles from an equiangular enneagram, ⟨9/2⟩

-

Regular {9/2}, p9

-

Spirolateral (1,1,5)100°, i6

-

Spirolateral 3100°, g3

- 60° internal angles from an equiangular triple-wound triangle, ⟨9/3⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r6

-

Irregular, a1

-

Irregular, a1

-

Irregular, a1

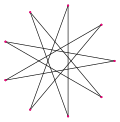

- 20° internal angles from an equiangular enneagram, ⟨9/4⟩

-

Regular {9/4}, r18

-

Spirolateral 320°, g3

-

Irregular, i2

Equiangular decagons

[edit]Direct equiangular decagons, ⟨10⟩, ⟨10/2⟩, ⟨10/3⟩, ⟨10/4⟩, have 144°, 108°, 72° and 36° internal angles respectively.

- 144° internal angles from an equiangular decagon ⟨10⟩

-

Regular, r20

-

Spirolateral (1,2)144°, p10

-

Spirolateral (1…5)144°, g2

- 108° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound pentagon ⟨10/2⟩

-

Regular, degenerate

-

Spirolateral (1,2)108°, p10

-

Irregular, p2

- 72° internal angles from an equiangular decagram ⟨10/3⟩

-

Regular {10/3}, r20

-

Isogonal, p10

-

Spirolateral (1,2)72°, p10

-

Irregular, i4

-

Spirolateral (1…5)72°, g2

- 36° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound pentagram ⟨10/4⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r10

-

Spirolateral (1,2)36°, p10

-

Isogonal, p10

-

Isogonal, p10

-

Irregular, p2

-

Irregular, p2

-

Irregular, p2

Equiangular hendecagons

[edit]Direct equiangular hendecagons, ⟨11⟩, ⟨11/2⟩, ⟨11/3⟩, ⟨11/4⟩, and ⟨11/5⟩ have 147 3/11°, 114 6/11°, 81 9/11°, 49 1/11°, and 16 4/11° internal angles respectively.

- 147° internal angles from an equiangular hendecagon, ⟨11⟩

-

Regular, {11}, r22

- 114° internal angles from an equiangular hendecagram, ⟨11/2⟩

-

Regular {11/2}, r22

- 81° internal angles from an equiangular hendecagram, ⟨11/3⟩

-

Regular {11/3}, r22

- 49° internal angles from an equiangular hendecagram, ⟨11/4⟩

-

Regular {11/4}, r22

- 16° internal angles from an equiangular hendecagram, ⟨11/5⟩

-

Regular {11/5}, r22

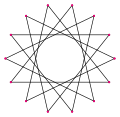

Equiangular dodecagons

[edit]Direct equiangular dodecagons, ⟨12⟩, ⟨12/2⟩, ⟨12/3⟩, ⟨12/4⟩, and ⟨12/5⟩ have 150°, 120°, 90°, 60°, and 30° internal angles respectively.

- 150° internal angles from an equiangular dodecagon, ⟨12⟩

Convex solutions with integer edge lengths may be tiled by pattern blocks, squares, equilateral triangles, and 30° rhombi.[6]

-

Regular, {12}, r24

-

Isogonal, p12

-

Spirolateral (1,2)150°, p12

-

Spirolateral (1…3)150°, g4

-

Spirolateral (1…4)150°, g3

-

Spirolateral (1…6)150°, g2

- 120° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound hexagon, ⟨12/2⟩

-

Regular degenerate, r12

-

Spirolateral, (1…4)120°, g3

-

Irregular, d2

-

Irregular, d2

- 90° internal angles from an equiangular triple-wound square, ⟨12/3⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r8

-

Spirolateral (1…3)90°, g2

-

Spirolateral (2…4)90°, g4

-

Spirolateral (1,1,3)90°, i8

-

Spirolateral (1,2,2)90°, i8

-

Spirolateral (1…6)90°, g2

-

Irregular, a1

- 60° internal angles from an equiangular quadruple-wound triangle, ⟨12/4⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r6

-

Spirolateral (1,3,5,1)60°, p6

-

Spirolateral (1…4)60°, g3

-

Irregular, a1

- 30° internal angles from an equiangular dodecagram, ⟨12/5⟩

-

Regular {12/5}, r24

-

Isogonal, p12

-

Spirolateral (1,2)30°, p12

-

Spirolateral (1…3)30°, g4

-

Spirolateral (1…4)30°, g3

-

Spirolateral (1…6)30°, g2

Equiangular tetradecagons

[edit]Direct equiangular tetradecagons, ⟨14⟩, ⟨14/2⟩, ⟨14/3⟩, ⟨14/4⟩, and ⟨14/5⟩, ⟨14/6⟩, have 154 2/7°, 128 4/7°, 102 6/7°, 77 1/7°, 51 3/7° and 25 5/7° internal angles respectively.

- 154.28° internal angles from an equiangular tetradecagon, ⟨14⟩

-

Regular {14}, r28

-

Isogonal, t{7}, p14

- 128.57° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound regular heptagon, ⟨14/2⟩

-

Regular degenerate, r14

-

Isogonal, t{7/2}, p14

-

Spirolateral 2128.57°

- 102.85° internal angles from an equiangular tetradecagram, ⟨14/3⟩

-

Regular {14/3}, r28

-

Isogonal t{7/3}, p14

- 77.14° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound heptagram ⟨14/4⟩

-

Regular degenerate, r14

-

Isogonal, p14

-

Isogonal, p14

-

Spirolateral 277.14°

- 51.43° internal angles from an equiangular tetradecagram, ⟨14/5⟩

-

Regular {14/5}, r28

-

Isogonal, p14

-

Isogonal, p14

- 25.71° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound heptagram, ⟨14/6⟩

-

Regular degenerate, r14

-

Isogonal, p14

-

Isogonal, p14

-

Isogonal, p14

-

Irregular, d2

Equiangular pentadecagons

[edit]Direct equiangular pentadecagons, ⟨15⟩, ⟨15/2⟩, ⟨15/3⟩, ⟨15/4⟩, ⟨15/5⟩, ⟨15/6⟩, and ⟨15/7⟩, have 156°, 132°, 108°, 84°, 60° and 12° internal angles respectively.

- 156° internal angles from an equiangular pentadecagon, ⟨15⟩

-

Regular, {15}, r30

- 132° internal angles from an equiangular pentadecagram, ⟨15/2⟩

-

Regular, {15/2}, r30

- 108° internal angles from an equiangular triple-wound pentagon, ⟨15/3⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r10

-

spirolateral (1…3)108°, g5

- 84° internal angles from an equiangular pentadecagram, ⟨15/4⟩

-

Regular, {15/4}, r30

- 60° internal angles from an equiangular 5-wound triangle, ⟨15/5⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r6

-

Irregular, a1

- 36° internal angles from an equiangular triple-wound pentagram, ⟨15/6⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r10

-

Irregular, a1

-

Spirolateral (1…4)36°, g5

- 12° internal angles from an equiangular pentadecagram, ⟨15/7⟩

-

Regular, {15/7}, r30

Equiangular hexadecagons

[edit]Direct equiangular hexadecagons, ⟨16⟩, ⟨16/2⟩, ⟨16/3⟩, ⟨16/4⟩, ⟨16/5⟩, ⟨16/6⟩, and ⟨16/7⟩, have 157.5°, 135°, 112.5°, 90°, 67.5° 45° and 22.5° internal angles respectively.

- 157.5° internal angles from an equiangular hexadecagon, ⟨16⟩

-

Regular, {16}, r32

-

Isogonal, t{8}, p16

-

Spirolateral (1…4)157.5°, g4

- 135° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound octagon, ⟨16/2⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r16

-

Irregular, p16

- 112.5° internal angles from an equiangular hexadecagram, ⟨16/3⟩

-

Regular, {16/3}, r32

- 90° internal angles from an equiangular 4-wound square, ⟨16/4⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r8

-

Irregular, a1

- 67.5° internal angles from an equiangular hexadecagram, ⟨16/5⟩

-

Regular, {16/5}, r32

- 45° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound regular octagram, ⟨16/6⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r16

-

spirolateral (1…3)45°, g8

- 22.5° internal angles from an equiangular hexadecagram, ⟨16/7⟩

-

Regular, {16/7}, r32

-

Isogonal, p16

Equiangular octadecagons

[edit]Direct equiangular octadecagons, <18}, ⟨18/2⟩, ⟨18/3⟩, ⟨18/4⟩, ⟨18/5⟩, ⟨18/6⟩, ⟨18/7⟩, and ⟨18/8⟩, have 160°, 140°, 120°, 100°, 80°, 60°, 40° and 20° internal angles respectively.

- 160° internal angles from an equiangular octadecagon, ⟨18⟩

-

Regular, {18}, r36

-

Isogonal, t{9}, p18

- 140° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound enneagon, ⟨18/2⟩

-

Regular, degenerate

-

Spirolateral 2140°, p18

- 120° internal angles of an equiangular 3-wound hexagon ⟨18/3⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r18

-

irregular, a1

- 100° internal angles of an equiangular double-wound enneagram ⟨18/4⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r18

-

Spirolateral 2100°, g3

- 80° internal angles of an equiangular octadecagram {18/5}

-

Regular, {18/5}, r36

- 60° internal angles of an equiangular 6-wound triangle ⟨18/6⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r6

-

irregular, a1

- 40° internal angles of an equiangular octadecagram ⟨18/7⟩

-

Regular, {18/7}, r36

-

Isogonal, p18

-

Isogonal, p18

-

Isogonal, p18

- 20° internal angles of an equiangular double-wound enneagram ⟨18/8⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r18

-

Isogonal, p18

-

Isogonal, p18

-

Isogonal, p18

-

Isogonal, p18

-

Spirolateral 220°, p18

-

Spirolateral 620°, g3

Equiangular icosagons

[edit]Direct equiangular icosagon, ⟨20⟩, ⟨20/3⟩, ⟨20/4⟩, ⟨20/5⟩, ⟨20/6⟩, ⟨20/7⟩, and ⟨20/9⟩, have 162°, 126°, 108°, 90°, 72°, 54° and 18° internal angles respectively.

- 162° internal angles from an equiangular icosagon, ⟨20⟩

-

Regular, {20}, r40

-

Spirolateral (1,3)162°, p20

- 144° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound decagon, ⟨20/2⟩

-

Regular, degenerate, r20

-

Spirolateral (1…4)144°, g5

- 126° internal angles from an equiangular icosagram, ⟨20/3⟩

-

Regular {20/3}, p40

-

Spirolateral (1,3)126°, p20

- 108° internal angles from an equiangular 4-wound pentagon, ⟨20/4⟩

-

Regular degenerate, r10

-

Spirolateral (1…4)108°, g5

-

Irregular, a1

- 90° internal angles from an equiangular 5-wound square, ⟨20/5⟩

-

Regular degenerate, r8

-

Spirolateral (1…5)90°, g4

-

Spirolateral (1,2,3,2,1)90°, i8

- 72° internal angles from an equiangular double-wound decagram, ⟨20/6⟩

-

Regular degenerate, r20

-

Spirolateral (1,2)72°, p10

-

Spirolateral (1…4)72°, g5

- 54° internal angles from an equiangular icosagram, ⟨20/7⟩

-

Regular {20/7}, r40

-

Isogonal, p20

-

Isogonal, p20

-

Isogonal, p20

- 36° internal angles from an equiangular quadruple-wound pentagram, ⟨20/8⟩

-

Regular degenerate, r10

-

Spirolateral (1…4)36°, g5

-

irregular, a1

- 18° internal angles from an equiangular icosagram, ⟨20/9⟩

-

Regular {20/9}, r40

-

Isogonal, p20

-

Isogonal, p20

-

Isogonal, p20

-

Isogonal, p20

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Marius Munteanu, Laura Munteanu, Rational Equiangular Polygons Applied Mathematics, Vol.4 No.10, October 2013

- ^ Abboud, Elias (2010). "Viviani's Theorem and Its Extension". The College Mathematics Journal. 41 (3): 203–211. doi:10.4169/074683410x488683.

- ^ De Villiers, Michael, "Equiangular cyclic and equilateral circumscribed polygons", Mathematical Gazette 95, March 2011, 102-107.

- ^ McLean, K. Robin (2004). "A powerful algebraic tool for equiangular polygons". Mathematical Gazette (88): 513–514. doi:10.1017/S002555720017617X.

- ^ Bras-Amorós, M.; Pujol, M. (2015). "Side Lengths of Equiangular Polygons (as seen by a coding theorist)". The American Mathematical Monthly. 122 (5): 476–478. doi:10.4169/amer.math.monthly.122.5.476.

- ^ a b c d e Ball, Derek (2002), "Equiangular polygons", The Mathematical Gazette, 86 (507): 396–407, doi:10.2307/3621131, JSTOR 3621131, S2CID 233358516.

- Williams, R. The Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure: A Source Book of Design. New York: Dover Publications, 1979. p. 32

External links

[edit]- A Property of Equiangular Polygons: What Is It About? a discussion of Viviani's theorem at Cut-the-knot.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Equiangular Polygon". MathWorld.