Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tridecagon

View on Wikipedia| Regular tridecagon | |

|---|---|

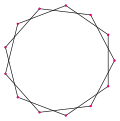

A regular tridecagon | |

| Type | Regular polygon |

| Edges and vertices | 13 |

| Schläfli symbol | {13} |

| Coxeter–Dynkin diagrams | |

| Symmetry group | Dihedral (D13), order 2×13 |

| Internal angle (degrees) | ≈152.308° |

| Properties | Convex, cyclic, equilateral, isogonal, isotoxal |

| Dual polygon | Self |

In geometry, a tridecagon or triskaidecagon or 13-gon is a thirteen-sided polygon.

Regular tridecagon

[edit]A regular tridecagon is represented by Schläfli symbol {13}.

The measure of each internal angle of a regular tridecagon is approximately 152.308 degrees, and the area with side length a is given by

Construction

[edit]As 13 is a Pierpont prime but not a Fermat prime, the regular tridecagon cannot be constructed using a compass and straightedge. However, it is constructible using neusis, or angle trisection.

The following is an animation from a neusis construction of a regular tridecagon with radius of circumcircle according to Andrew M. Gleason,[1] based on the angle trisection by means of the Tomahawk (light blue).

Symmetry

[edit]

The regular tridecagon has Dih13 symmetry, order 26. Since 13 is a prime number there is one subgroup with dihedral symmetry: Dih1, and 2 cyclic group symmetries: Z13, and Z1.

These 4 symmetries can be seen in 4 distinct symmetries on the tridecagon. John Conway labels these by a letter and group order.[2] Full symmetry of the regular form is r26 and no symmetry is labeled a1. The dihedral symmetries are divided depending on whether they pass through vertices (d for diagonal) or edges (p for perpendiculars), and i when reflection lines path through both edges and vertices. Cyclic symmetries in the middle column are labeled as g for their central gyration orders.

Each subgroup symmetry allows one or more degrees of freedom for irregular forms. Only the g13 subgroup has no degrees of freedom but can be seen as directed edges.

Numismatic use

[edit]The regular tridecagon is used as the shape of the Czech 20 korun coin.[3]

Related polygons

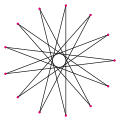

[edit]A tridecagram is a 13-sided star polygon. There are 5 regular forms given by Schläfli symbols: {13/2}, {13/3}, {13/4}, {13/5}, and {13/6}. Since 13 is prime, none of the tridecagrams are compound figures.

| Tridecagrams | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Picture |  {13/2} |

{13/3} |

{13/4} |

{13/5} |

{13/6} | ||||||

| Internal angle | ≈124.615° | ≈96.9231° | ≈69.2308° | ≈41.5385° | ≈13.8462° | ||||||

Although 13-sided stars appear in the Topkapı Scroll, they are not of these regular forms.[4]

Petrie polygons

[edit]The regular tridecagon is the Petrie polygon of the 12-simplex:

| A12 |

|---|

12-simplex |

References

[edit]- ^ Gleason, Andrew Mattei (March 1988). "Angle trisection, the heptagon, and the triskaidecagon p. 192–194 (p. 193 Fig.4)" (PDF). The American Mathematical Monthly. 95 (3): 186–194. doi:10.2307/2323624. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-19. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, (2008) The Symmetries of Things, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 20, Generalized Schaefli symbols, Types of symmetry of a polygon pp. 275–278)

- ^ Colin R. Bruce, II, George Cuhaj, and Thomas Michael, 2007 Standard Catalog of World Coins, Krause Publications, 2006, ISBN 0896894290, p. 81.

- ^ Cromwell, Peter R. (2010). "Islamic geometric designs from the Topkapı Scroll I: unusual arrangements of stars". Journal of Mathematics and the Arts. 4 (2): 73–85. doi:10.1080/17513470903311669. MR 2786387.

External links

[edit]Tridecagon

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Basic Properties

Definition

A tridecagon is a polygon consisting of exactly 13 sides and 13 vertices, forming a closed plane figure.[1][5] The name "tridecagon" is derived from Greek roots, with "trideka" meaning thirteen and "gonia" meaning angle, reflecting its 13-sided structure.[6][7] Tridecagons may be classified as simple or complex; simple tridecagons do not self-intersect and can be either convex, where all interior angles are less than 180 degrees, or concave, with at least one interior angle greater than 180 degrees, whereas complex tridecagons feature self-intersections.[8] In general, tridecagons are not required to have equal sides or angles, though a regular tridecagon possesses both equilateral and equiangular properties.[8]Fundamental Properties

A tridecagon is a polygon with exactly 13 sides and 13 vertices, where the number of sides equals the number of vertices by definition.[8] The sum of the interior angles of any simple tridecagon is given by the general formula for an -gon, , which for yields . In radians, this sum is . This result holds for any simple polygon regardless of regularity or convexity, derived from triangulating the polygon into triangles, each contributing or radians to the total.[8] For simple tridecagons, each interior angle measures greater than and less than . In convex tridecagons, all interior angles are less than , while concave variants have at least one reflex interior angle between and . These bounds ensure the polygon remains simple without self-intersections.[9][10] The perimeter of a tridecagon is the sum of its 13 side lengths, with no assumptions of equality among the sides. In the special case of a regular tridecagon, all sides are equal, as detailed in the geometric features section.[8]Regular Tridecagon

Geometric Features

A regular tridecagon is a 13-sided polygon where all sides are of equal length and all interior angles are equal, making it equilateral and equiangular.[4] This uniformity results in a highly symmetric figure that appears nearly circular due to the large number of sides, yet retains distinct polygonal characteristics.[4] The Schläfli symbol for the regular tridecagon is {13}, denoting its regular polygonal nature with 13 sides.[11] As a convex polygon, it lies entirely on one side of each of its edges, ensuring no internal angles exceed 180 degrees.[4] It is cyclic, meaning all vertices lie on a common circumscribed circle, and tangential, as it possesses an incircle tangent to all sides, a property true for all regular polygons.[4] For a regular tridecagon with unit side length , the circumradius (distance from center to a vertex) is given by and the apothem (distance from center to the midpoint of a side) by These relations highlight the proportional geometry, where the circumradius exceeds the apothem by a factor related to the central angle of approximately 27.692 degrees per sector.[4] Visually, the regular tridecagon cannot tile the Euclidean plane without gaps or overlaps, as its interior angles do not divide 360 degrees evenly, preventing seamless adjacency of multiple copies around a point.[12] This contrasts with triangular, square, and hexagonal tilings, underscoring the tridecagon's role in more complex or non-periodic arrangements.[12]Angle and Side Calculations

The interior angle of a regular tridecagon is calculated using the formula for the interior angle of a regular -gon: , where . Substituting the value gives .[4] The exterior angle, which is the angle through which the polygon turns at each vertex, is .[4] This value also represents the central angle subtended by each side at the center of the tridecagon, or radians when considering the polygon inscribed in a unit circle.[4] For a regular tridecagon inscribed in a unit circle (circumradius ), the side length is the chord length corresponding to the central angle, given by .[4] The area of a regular tridecagon with side length is . Alternatively, in terms of the circumradius , the area is .[4]Construction Methods

Theoretical Limitations

The construction of a regular tridecagon using only a straightedge and compass is theoretically impossible, a result stemming from the fact that 13 is a prime number whose associated central angle is not a constructible angle.[13] According to the Gauss-Wantzel theorem, a regular -gon is constructible if and only if , where the are distinct Fermat primes; since 13 is prime but not a Fermat prime (the known Fermat primes being 3, 5, 17, 257, and 65537), the tridecagon falls outside this criterion.[13] This theorem, articulated by Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1801 for sufficient conditions and rigorously completed by Pierre Wantzel in 1837 for necessity, relies on field theory to show that constructible lengths correspond to field extensions of degree a power of 2 over the rationals.[14] The core obstruction lies in the minimal polynomial of , which is irreducible over the rationals and has degree 6.[15] This degree arises because the real subfield of the 13th cyclotomic field has degree , where is Euler's totient function, and 6 is not a power of 2, preventing the coordinates of the tridecagon's vertices from being obtained through quadratic extensions alone.[15] The 13th cyclotomic polynomial is , an irreducible polynomial of degree 12 that generates the cyclotomic field , where .[16] Solving for the roots requires extensions beyond those achievable with straightedge and compass operations. This impossibility was established in the 19th century, paralleling the case of the regular heptagon (n=7), which also cannot be constructed exactly for similar reasons involving a degree-3 minimal polynomial for .[14] However, while some non-constructible regular polygons admit constructible star variants under relaxed conditions, the prime nature of 13 ensures that star tridecagons, such as {13/3} or {13/5}, share the same field-theoretic barriers and are likewise impossible with classical tools.[13]Practical Approximations

One practical method for approximating a regular tridecagon involves placing its vertices on the unit circle using parametric coordinates. The vertices are located at points for to , which can be computed numerically and plotted for visualization or further geometric analysis. In modern drawing applications, a regular tridecagon can be approximated with high precision using tools like protractors for manual sketching or computer-aided design (CAD) software for digital rendering. For instance, software such as AutoCAD allows users to draw regular polygons with up to 1024 sides via the POLYGON command, specifying 13 sides and the circumradius or inscribed circle, yielding near-exact results limited only by computational precision.[17] Historical approximations of the tridecagon have employed alternative tools beyond the compass and straightedge, such as the marked ruler (neusis construction) and origami folding, which enable greater accuracy for non-constructible polygons. Using a marked ruler, the tridecagon can be constructed exactly through angle trisection techniques, as detailed in methods based on solving the associated cubic equations for the vertex angles.[18] Similarly, origami methods allow for the folding of a regular tridecagon by simultaneously creasing multiple layers to achieve the required 360°/13 ≈ 27.692° central angle divisions, offering practical accuracy superior to iterative compass divisions alone.[19] Attempts to approximate a tridecagon using only a compass and straightedge, such as by iteratively marking arcs to divide the circle into 13 parts, introduce cumulative angular errors due to the inability to exactly trisect angles or solve the minimal polynomial of degree 6 over the rationals. For example, a common approximation method involves setting the compass to a fraction of the radius (e.g., approximately 13/(2×13 + 1) = 0.46 times the radius) and stepping around the circumference; this yields central angle deviations of about 0.25° per step, resulting in a total misalignment of roughly 3.25° after 13 steps, sufficient for visual but not precise applications.[20]Symmetry

Dihedral Symmetry Group

The dihedral symmetry group of the regular tridecagon is the dihedral group , which consists of all isometries that map the tridecagon to itself and has order 26.[21] This group is generated by a rotation by the central angle and a reflection , encompassing 13 rotations and 13 reflections.[21] The rotations are given by for , forming the cyclic subgroup of order 13.[21] Since 13 is prime, the rotation subgroup is cyclic of prime order, possessing only the trivial subgroups and itself, which underscores its simple algebraic structure.[21] The full dihedral group includes the reflections for , each corresponding to a reflection across one of the 13 axes of symmetry.[21] For the odd-sided tridecagon, these axes each pass through one vertex and the midpoint of the opposite side, alternating in their geometric placement around the polygon.[21] The abstract structure of is captured by its group presentation , where the relation encodes how reflections conjugate rotations to their inverses.[21] This presentation highlights the non-abelian nature of the group, as the rotations and reflections do not commute in general.[21]Visual Representations

Visual representations of the regular tridecagon often include diagrams that label its vertices and illustrate the 13 axes of reflection symmetry, each passing through one vertex and the midpoint of the opposite side due to the odd number of sides.[22] These diagrams highlight how the symmetries align the polygon onto itself under reflections, emphasizing the dihedral group elements briefly referenced in symmetry discussions. Animations of the tridecagon typically depict continuous or discrete rotations by multiples of , demonstrating the 13 distinct rotational positions before returning to the original orientation. The dual polygon of a regular tridecagon is another regular tridecagon, rendering it self-dual among regular polygons with an odd number of sides. This self-duality is visually evident when the original polygon's vertices correspond to the dual's edge midpoints, producing an identical form rotated by half the central angle. For edge-coloring visualizations, the tridecagon requires three colors to properly color its edges without adjacent edges sharing the same color, as it forms an odd-length cycle graph with chromatic index 3.[23] Diagrams often show alternating colors with a third introduced to resolve the odd-cycle conflict, using patterns like two colors for 12 edges and the third for the closing edge.Applications

Numismatic Designs

The tridecagon has been incorporated into modern numismatic designs primarily as the overall shape of coins, leveraging its distinctive 13-sided form for visual identification and symbolic purposes. The Czech Republic's 20 korun circulating coin, introduced in 1993 by the Czech National Bank, is a prominent example of a regular tridecagon in everyday currency. Made of brass-plated steel with a diameter of 26 mm and weight of 8.43 g, the coin features the crowned Czech lion on the obverse and Saint Wenceslas on horseback on the reverse, aiding in its differentiation from other denominations through the non-circular profile.[24] Another notable instance is the Royal Canadian Mint's 2019 $50 fine silver commemorative coin honoring the Centennial Flame monument on Parliament Hill. This 3 oz. pure silver piece (99.99% fineness) adopts a tridecagon shape to mirror the monument's 13-sided basin, which was updated in 2017 to include symbols for all 13 provinces and territories of Canada after Nunavut's addition. The coin's ultra-high relief design captures the eternal flame in an antique finish, emphasizing national unity and the 1967 centennial of Confederation. With a limited mintage of 2,500, it represents a deliberate choice to evoke the monument's geometry while highlighting Canada's federal structure.[25][26] The design rationale for these tridecagon coins often ties into the number 13's broader symbolism, such as the approximate 13 lunar cycles in a solar year, which has historical roots in calendrical systems across cultures. In the Canadian example, the 13 sides specifically symbolize the completeness of Canada's provincial and territorial federation, promoting themes of unity and inclusivity rather than superstition. Although 13 is viewed as unlucky in some Western traditions—stemming from associations with events like the Last Supper or Norse mythology—these coin designs repurpose it positively for national identity.[27] Minting tridecagon-shaped coins presents technical challenges due to the regular tridecagon's non-constructibility with classical compass and straightedge tools, as established by Pierre Wantzel in 1837, since 13 is a prime not of the form 2^k + 1. As a result, modern mints employ numerical approximations—such as solving for vertex coordinates using trigonometric functions or computer-aided design—to achieve near-regular sides and angles, ensuring uniformity in production via high-precision dies. This approach, briefly referencing practical approximation methods like iterative angle divisions, allows for accurate replication despite the geometric limitations.Architectural and Artistic Uses

The tridecagon, owing to its non-constructibility with compass and straightedge, appears rarely in precise form within architecture but features in complex geometric designs through approximations or related star patterns. In Islamic architecture, 13-point girih tiles—interlaced strapwork incorporating tridecagonal symmetry—were employed as early as the 11th century, as seen in the mihrab of the Barsian Mosque in Iran, where sweeping 13-point patterns contribute to the intricate ornamental scheme.[28] These designs highlight the tridecagon's role in evoking infinite repetition and cosmic order, a hallmark of Seljuk-era aesthetics. In artistic contexts beyond architecture, tridecagonal motifs emerge in sacred geometry and modern digital creations, symbolizing cycles and transformation due to the prime number 13's association with completeness and rarity. For instance, the tridecagram (a 13-pointed star polygon derived from the tridecagon) represents thresholds and fundamental patterns in esoteric art traditions.[29] Digital artists leverage D_{13} dihedral symmetry—the tridecagon's rotational and reflectional group—to generate fractal-like kaleidoscopic visuals, producing non-repeating patterns that explore chaos and harmony in computational media.[30] Such applications underscore the shape's conceptual appeal in contemporary design, where software enables exact renderings unattainable in traditional media.Related Polygons

Star Variants

A star tridecagon, also known as a tridecagram, is a non-convex isogonal polygon consisting of 13 equal sides and angles, formed by connecting every k-th vertex of 13 equally spaced points on a circle.[31] These are denoted by the Schläfli symbol {13/k}, where k is an integer from 2 to 6, as k=1 yields the convex tridecagon and higher k values produce enantiomorphs (mirror images).[31] The parameter k represents the step or density, dictating the winding number—the number of full rotations the path makes around the center—and the pattern of vertex connections, resulting in self-intersecting edges that create a star-shaped figure.[31] The five distinct star variants are {13/2}, {13/3}, {13/4}, {13/5}, and {13/6}, each with increasing density from 2 to 6, which measures the number of enclosed regions or the winding multiplicity of the boundary relative to the center.[31] For a regular star polygon {n/k}, the density is simply k when k < n/2 and gcd(n, k)=1, as is the case here since 13 is prime.[31] This density arises from the topological winding of the edges, where each increment in k adds more intersections and interior layers without altering the overall 13-fold rotational symmetry.[31] Visually, these star tridecagons differ markedly from the simple convex outline of the regular tridecagon by featuring dense interlacing paths of edges that cross multiple times, forming a complex, petal-like or spiky enclosure rather than a smooth boundary.[31] For instance, {13/2} produces a sparsely intersecting star with two layers of winding, while {13/6} exhibits the most intricate overlaps, approaching a near-circular form filled with six internal densities.[31]Petrie and Compound Forms

The regular tridecagon appears as the Petrie polygon in several regular higher-dimensional polytopes, most notably the 12-simplex. A Petrie polygon is defined as a closed skew polygon on the surface of a polytope such that every pair of consecutive edges lies on a distinct face, but no three consecutive edges do. For the 12-simplex, this results in a regular 13-sided skew polygon that cycles through all 13 vertices of the polytope in a non-planar path, providing a key projection for visualizing its structure.[32] This property extends to other polytopes where the tridecagon serves as a Petrie polygon in their orthogonal projections, highlighting the role of odd-sided polygons in higher-dimensional geometry. The construction of such Petrie polygons for simplices follows from the symmetry of the Coxeter group A_{12}, where the path alternates between facets in a manner that yields the 13-gon boundary. Regarding compound forms, the prime number of sides in the tridecagon (13) precludes non-trivial regular compounds in the plane, as regular polygonal compounds require the density parameter to allow decomposition into multiple isomorphic components sharing the same vertex set, which is impossible for prime-sided polygons without reducing to a single component. Unlike composite-sided polygons such as the enneagon {9/3}, which decomposes into three equilateral triangles, no such regular interweaving exists for tridecagons. In higher dimensions, tridecagons may participate in compounds as faces or sections of uniform polytopes, but these are not direct compounds of multiple tridecagons.References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tridecagon