Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tumed

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

The Tümed (Mongolian: Түмэд; Chinese: 土默特部; "The many or ten thousands" derived from Tumen) are a Mongol subgroup. They live in Tumed Left Banner, district of Hohhot and Tumed Right Banner, district of Baotou in China. Most engage in sedentary agriculture, living in mixed communities in the suburbs of Hohhot. Parts of them live along Chaoyang, Liaoning.[1] There are the Tumeds in the soums of Mandal-Ovoo, Bulgan, Tsogt-Ovoo, Tsogttsetsii, Manlai, Khurmen, Bayandalai and Sevrei of Ömnögovi Aimag, Mongolia.

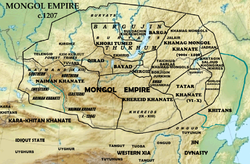

From the beginning of the 9th century to the beginning of the 13th century, the Khori-Tumed lived near the western side of Lake Baikal. They lived in what is now southern Irkutsk Oblast, in some parts of Tuva and in southwestern Buryatia.[2] In 1207, Genghis Khan, after conquering the Khori-Tumed, decided to move some of these groups south and these people eventually settled in the southern parts of the Great Gobi Desert. But it seems that the Tumed people had no strong connection with those forest people in Siberia.

The Tumeds first appeared as the tribe of the Mongolian warlord Dogolon, who was taishi in the mid-15th century. In Mongolian chronicles, they were called seven Tumeds or twelve Tumeds. Because the Kharchin and other Mongol clans joined their league, they were probably called 12 Tumeds later on. Under Dayan Khan (1464-1517/1543) and his successors, the Tumeds formed the right wing of the eastern Mongols. The Tumeds reached their peak under the rule of Altan Khan (1507–1582) in the mid-16th century. They raided the Ming dynasty and attacked the Four Oirats. The Tumeds under Altan Khan recaptured Karakorum from the hands of the Oirats but the outcome of the war was not decisive in the 16th century. They are also famous for being the first of the Mongol tribes converted to Buddhism.

They submitted to the Qing dynasty and allied against the Chahar Mongols in the early 17th century. They were included in Josotu league of the Qing.

The Tumed were Sinicized linguistically in the late 19th century, and by the early 20th century. Many of their leaders rose to the very top government, party, and military positions in the newly founded IMAR, and some attained leading national posts in Beijing and elsewhere. Ulanhu (1906–1988), a Tumed Mongol born near Huhhot, the capital of Inner Mongolia, who dominated the politics of the region until his death in 1989, and was the highest-ranking Mongol in the Chinese Communist Party. After the 1920s, as the Tumed began to interact with other Mongols, they began to feel an acute sense of inadequacy regarding their Mongolian language skills.[3] In the 1950s, they set up many nationality (mínzú) primary schools and middle schools that recruited only Mongolian students. In these schools, Mongolian was taught as a subject, one considered of equal importance to Chinese, though all other subjects were taught in Chinese. During the Cultural Revolution years, 1966–1976, Mongolian instruction was largely abolished. A new attempt to provide a Mongol education began in September 1979.

The Tumed banner built a "Mongolian Nationality Primary School" in October 1982 in the banner center. The school had eight classes divided into three grades, with 201 boarding pupils, all taught in Mongolian, while Chinese was taught only starting from grade 5.[4][5]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Eastern Tumed Right Banner". CHRISTIE'S. 1907.

- ^ History of Mongolia, Volume II, 2003

- ^ Huhehaote 2000

- ^ Tumote 1987:634-659

- ^ Perry, Elizabeth J.; Selden, Mark (2010). Chinese society : change, conflict and resistance (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 273–274. ISBN 9780415560733. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

External links

[edit]- Монгол угсаатны хэлний бүрэлдэхүүн in Mongolian