Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Classifications of snow

View on Wikipedia

Classifications of snow describe and categorize the attributes of snow-generating weather events, including the individual crystals both in the air and on the ground, and the deposited snow pack as it changes over time. Snow can be classified by describing the weather event that is producing it, the shape of its ice crystals or flakes, how it collects on the ground, and thereafter how it changes form and composition. Depending on the status of the snow in the air or on the ground, a different classification applies.

Snowfall arises from a variety of events that vary in intensity and cause, subject to classification by weather bureaus. Some snowstorms are part of a larger weather pattern. Other snowfall occurs from lake effects or atmospheric instability near mountains. Falling snow takes many different forms, depending on atmospheric conditions, especially vapor content and temperature, as it falls to the ground. Once on the ground, snow crystals metamorphose into different shapes, influenced by wind, freeze-thaw and sublimation. Snow on the ground forms a variety of shapes, formed by wind and thermal processes, all subject to formal classifications both by scientists and by ski resorts. Those who work and play in snowy landscapes have informal classifications, as well.

There is a long history of northern and alpine cultures describing snow in their different languages, including Inupiat, Russian and Finnish.[1] However, the lore about the multiplicity of Eskimo words for snow originates from controversial scholarship on a topic that is difficult to define, because of the structures of the languages involved.[2]

Classification of snow events

[edit]Snow events reflect the type of storm that generates them and the type of precipitation that results. Classification systems use rates of deposition, types of precipitation, visibility, duration and wind speed to characterize such events.

Snow-producing events

[edit]

The following terms are consistent with the classifications of United States National Weather Service and the Meteorological Service of Canada:[3]

- Blizzard – Characterized by sustained wind or frequent gusts of 56 kilometres per hour (35 mph) or greater and falling or blowing snow that frequently lowers visibility to less than 400 metres (0.25 mi) over a period of 3 hours or longer.[4]

- Cold front – The leading edge of unstable cold air, replacing warmer, circulating around an extratropical cyclone, which may cause instability snow showers or squalls.[5]

- Extratropical cyclone (also nor'easter when in the North Atlantic) – May cause snow in the winter, especially in its northwest quadrant (in the Northern Hemisphere) where the wind comes from the northeast.[5]

- Lake-effect snow (also ocean-effect snow) – Occurs when relatively cold air flows over warm lake (or ocean) water to cause localized, convective snow bands.[6][7]

- Mountain snow – Orographic lift causes moist air to rise upslope on mountains to where freezing temperatures cause orographic snow.

- Snow flurry – An intermittent, light snowfall event of short duration with only a trace level of accumulation.[8]

- Snowsquall – A brief but intense period of moderate to heavy snowfall with strong, gusty surface winds and measurable snowfall.[9]

- Thundersnow – Occurs when a snowstorm generates lightning and thunder. It may occur in areas that are prone to a combination of wind and moisture triggers that promote instability, often downwind of lakes or in mountainous terrain. It may occur with intensifying extratropical cyclones. Such events are often associated with intense snowfall.[10]

- Warm front – Snow may fall as warm air initially over-rides cold in a warm front, circulating around an extratropical cyclone.[5]

- Winter storm – May constitute any combination of sleet, snow, ice, and wind that accumulates 18 centimetres (7 in) or more of snow in 12 hours or less; or 23 centimetres (9 in) or more in 24 hours or 1.3 centimetres (0.5 in) of ice.[11]

Precipitation

[edit]

Precipitation may be characterized by type and intensity.

Type

[edit]Frozen precipitation includes snow, snow pellets, snow grains, ice crystals, ice pellets, and hail.[12] Falling snow comprises ice crystals, growing in a hexagonal pattern and combining as snowflakes.[13] Ice crystals may be "any one of a number of macroscopic, crystalline forms in which ice appears, including hexagonal columns, hexagonal platelets, dendritic crystals, ice needles, and combinations of these forms".[14] Terms that refer to falling snow particles include:

- Ice crystals (also diamond dust) – Suspended in the atmosphere as needles, columns or plates at very low temperatures in a stable atmosphere.[15]

- Ice pellets – Two manifestations, sleet and small hail, that result in irregular spherical particles, which typically bounce upon impact. Sleet comprises grains of ice that form from refreezing of largely melted snowflakes when falling through into a frozen layer of air near the surface. Small hail forms from snow pellets encased in a thin layer of ice caused either by accretion of droplets or by refreezing of each particle's surface.[16]

- Hail – Forms in cumulonimbus clouds as irregular spheres of ice (hailstones) with a diameter of 5 mm or more.

- Snowflake – Grows from a single ice crystal and may have agglomerated with other crystals as it falls.[17]

- Snow grain (also granular snow) – Flattened and elongated agglomerations of crystals, typically less than 1 mm diameter, that include a range of crystal sizes and complexities to include a rime core and glaze coating. They typically originate in stratus clouds or from fog and fall in small quantities, not in showers.[18]

- Snow pellets (also soft hail, graupel, tapioca snow) – Spherical or conical ice particles, based on a snowlike structure, with diameters between 2 mm and 5 mm. They form by accretion of supercooled droplets near or slightly below the freezing point and rebound off hard surfaces upon landing.[19]

Intensity

[edit]In the US, the intensity of snowfall is characterized by visibility through the falling precipitation, as follows:[13]

- Light snow: visibility of 1 kilometre (1,100 yd) or greater

- Moderate snow: visibility between 1 kilometre (1,100 yd) and 0.5 kilometres (550 yd)

- Heavy snow: visibility of less than 0.5 kilometres (550 yd)

Snow crystal classification

[edit]

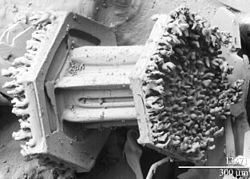

Ice approximates hexagonal symmetry in most of its atmospheric manifestations of a crystal lattice as snow. Temperature and vapor pressure determine the growth of the hexagonal crystal lattice in different forms that include columnar growth in the axis perpendicular to the hexagonal plane to form snow crystals.[14] Ukichiro Nakaya developed a crystal morphology diagram, relating crystal shape to the temperature and moisture conditions under which they formed.[21] Magono and Lee devised a classification of freshly formed snow crystals that includes 80 distinct shapes. They are summarized in the following principal snow crystal categories (with symbol):[22]

- Needle (N): Snow crystals may be simple or a combination of needles.

- Column (C): Snow crystals may be simple or a combination of columns.

- Plate (P): Snow crystals may be a regular crystal in one plane, a plane crystal with extensions (dendrites), a crystal with irregular number of branches, crystal with 12 branches, malformed crystal, radiating assemblage of plane branches.

- Column and plate combination (CP): Snow crystals may be a column with plane crystal at both ends, a bullet with plane crystals, a plane crystal with spatial extensions at ends.

- Side plane (S): Snow crystals may have extended side planes, some scalelike side planes, and some a combination of side planes, bullets, and columns.

- Rime (R): Rimed crystals may be densely rimed crystals, graupel-like crystals, or graupel.

- Irregular (I): Snow crystals include ice particles, rimed particles, broken pieces from a crystal, and miscellaneous crystals.

- Germ (G): Crystals may be a minute column, hexagonal plate, stellar crystal, assemblage of plates, irregular germ, or other skeletal form.

Classifications of snow on the ground

[edit]Classification of snow on the ground comes from two sources: the science community and the community of those who encounter it in their daily lives. Snow on the ground exists both as a material with varying properties and as a variety of structures, shaped by wind, sun, temperature, and precipitation.

Classification of snowpack material properties

[edit]The International Classification for Seasonal Snow on the Ground describes snow crystal classification, once it is deposited on the ground, that include grain shape and grain size. The system also characterizes the snowpack, as the individual crystals metamorphize and coalesce.[23] It uses the following characteristics (with units) to describe deposited snow: microstructure, grain shape, grain size (mm), snow density (kg/m3), snow hardness, liquid water content, snow temperature (°C), impurities (mass fraction), and layer thickness (cm). The grain shape is further characterized, using the following categories (with code): precipitation particles (PP), machine-made snow (MM), decomposing and fragmented precipitation particles (DF), rounded grains (RG), faceted crystals (FC), depth hoar (DH), surface hoar (SH), melt forms (MF), and ice formations (IF). Other measurements and characteristics are used as well, including a snow profile of a vertical section of the snowpack.[23] Some snowpack features include:

- Crust – A variety of processes can create a crust, a layer of snow on the surface of the snowpack that is stronger than the snow below, which may be powder snow. Crusts often result from partial melting of the snow surface by direct sunlight or warm air followed by re-freezing, but can also be created by wind or by surface water.[24] Snow travelers consider the thickness and resulting strength of a crust to determine whether it is "unbreakable", meaning that they will support the weight of the traveler or "breakable", meaning that it will not.[25]

- Depth hoar – Depth hoar comprises faceted snow crystals, usually poorly or completely unbonded (unsintered) to adjacent crystals, creating a weak zone in the snowpack. Depth hoar forms from metamorphism of the snowpack in response to a large temperature gradient between the warmer ground beneath the snowpack and the surface. The relatively high porosity (percentage of air space), relatively warm temperature (usually near freezing point), and unbonded weak snow in this layer can allow various organisms to live in it.[23]

- Machine-made – Machine-made artificial snow has two classifications: round, polycrystalline particles, which are produced by the freezing of water droplets expelled from a snow cannon, and shard-like ice plates, which are produced by the shaving of ice.[23]

- Surface hoar – Surface hoar is manifest as striated, usually flat, sometimes needle-like crystals, usually deposited as frost on a snow surface that is colder than the air. Crystals grow rapidly by transfer of moisture from the atmosphere onto the snow surface, which is cooled below ambient temperature by radiational cooling.[23] Subsequent snowfall can bury layers of surface hoar, incorporating them into the snowpack where they can form a weak layer.[26]

Classifications of snowpack surface and structure

[edit]In addition to having material properties, snowpacks have structure which can be characterized. These properties are primarily determined through the actions of wind, sun, and temperature. Such structures have been described by mountaineers and others encountering frozen landscapes, as follows:[26]

Wind-induced

[edit]- Cornice – Wind blowing over a ridge can create a compacted snowdrift with an overhanging top, called a cornice. Cornices present a hazard to mountaineers, because they are prone to break off.[26]

- Finger drift – A finger drift is a narrow snow drift (30 cm to 1 metre in width) crossing a roadway. Several finger drifts in succession resemble the fingers of a hand.[27]

- Pillow drift – A pillow drift is a snow drift crossing a roadway and usually 3 to 4.5 metres (10–15 feet) in width and 30 cm to 90 cm (1–3 feet) in depth.[28]

- Sastrugi – Sastrugi are snow surface features sculpted by wind into ridges and grooves up to 3 meters high,[29] with the ridges facing into the prevailing wind.[30]

- Snowdrift – Snowdrifts are wind-driven accumulations of snow deposited downwind of obstructions.[31]

- Wind crust – A layer of relatively stiff, hard snow formed by deposition of wind blown snow on the windward side of a ridge or other sheltered area. Wind crusts generally bond better to snowpack layers below and above them than wind slabs.[32]

- Wind slab – A layer of relatively stiff, hard snow formed by deposition of wind blown snow on the leeward side of a ridge or other sheltered area. Wind slabs can form over weaker, softer freshly fallen powder snow, creating an avalanche hazard on steep slopes.[32]

Sun or temperature-induced

[edit]- Firn – Firn is dense, granular snow, which has been in place for multiple years but which has not yet consolidated into glacial ice.[33]

- Névé – Névé is a young, granular type of snow which has been partially melted, refrozen and compacted, yet precedes the form of ice. This type of snow is associated with glacier formation through the process of nivation.[34] Névé that survives a full season of ablation turns into firn, which is both older and slightly denser.[33]

- Penitentes – Penitentes are snow formations, found at high elevations, which form of elongated, thin blades of hardened snow or ice up to 5 meters in height, closely spaced and pointing towards the general direction of the sun. They are evolved suncups.[35]

- Suncups – Suncups are polygonal depressions in a snow surface that form patterns with sharp narrow ridges separating smoothly concave quasi-periodic hollows. They form during the ablation (melting away) of snow from incident solar radiation in bright sunny conditions, sometimes enhanced by the insulating presence of dirt along the ridges.[36]

- Yukimarimo – Yukimarimo are balls of fine frost, formed at low temperatures on the Antarctic Plateau during light or calm winds.[37]

Ski resort classification

[edit]Ski resorts use standardized terminology to describe their snow conditions. In North America terms include:[38]

- Base snow – Snow that has been thoroughly consolidated.

- Frozen granular – Snow whose granules have frozen together.

- Loose granular – Snow with incohesive granules.

- Machine-made – Produced by snow cannons, and typically denser than natural snow.

- New snow – Snow that has fallen since the previous day's report.

- Packed powder – Powder snow that has been compressed by grooming or by ski traffic.

- Powder – Freshly fallen, uncompacted snow. The density and moisture content of powder snow can vary widely; snowfall in coastal regions and areas with higher humidity is usually heavier than a similar depth of snowfall in an arid or continental region. Light, dry (low moisture content, typically 4–7% water content) powder snow is prized by skiers and snowboarders.[38] It is often found in the Rocky Mountains of North America and in most regions in Japan.[26]

- Spring conditions – A variety of melting snow surfaces, including mushy powder or granular snow, which refreeze at night.

- Wet – Warm snow with a high moisture content.

Informal classification

[edit]Skiers and others living with snow provide informal terms for snow conditions that they encounter.

- Corn snow – Corn snow is coarse, granular snow, subject to freeze-thaw.[26]

- Crud – Crud covers varieties of snow that all but advanced skiers find impassable. Subtypes are (a) windblown powder with irregularly shaped crust patches and ridges, (b) heavy tracked spring snow re-frozen to leave a deeply rutted surface strewn with loose blocks, (c) a deep layer of heavy snow saturated by rain (although this may go by another term).[39]

- Packing snow – Packing snow is at or near the melting point, so that it can easily be packed into snowballs and thrown or used in the construction of a snowman, or a snow fort.[40]

- Slush – Slush is substantially melted snow with visible water in it.[41]

- Snirt – Snirt is an informal term for snow covered with dirt, especially where strong winds pick up topsoil from uncovered farm fields and blow it into nearby snowy areas. Also, dirty snow left over from plowing operations.[42]

- Spring snow – Spring snow describes a variety of temperature and moisture conditions with corn snow.[38]

- Watermelon snow – Watermelon snow is reddish pink, caused by a red-colored green algae called Chlamydomonas nivalis.[43]

In various cultures

[edit]Not surprisingly, in languages and cultures where snow is common, having different words for distinct weather conditions and types of snowfall is desirable for efficient communication.[44] Finnish,[45] Icelandic,[46] Norwegian,[47] Russian,[48][49] and Swedish[50] have multiple words and phrases relating to snow and snowfall, in some cases dozens or even hundreds, depending upon how one counts.

Studies of the Sámi languages of Norway, Sweden and Finland, conclude that the languages have anywhere from 180 snow- and ice-related words and as many as 300 different words for types of snow, tracks in snow, and conditions of the use of snow.[51][52]

The claim that Eskimo–Aleut languages (specifically, Yupik and Inuit) have an unusually large number of words for "snow", has been attributed to the work of anthropologist Franz Boas. Boas, who lived among Baffin islanders and learnt their language, reportedly included "only words representing meaningful distinctions" in his account.[53] A 2010 study follows the sometimes questionable scholarship regarding the question whether these languages have many more root words for "snow" than the English language.[54][53]

See also

[edit]- Glacier – Persistent body of ice that moves downhill under its own weight

- Ice – Frozen water; the solid state of water

- METAR – Format for weather reports used in aviation – a format for reporting weather information

- The wrong type of snow – Byword for euphemistic and pointless excuses

References

[edit]- ^ Pruitt, William O. Jr. (2005). "Why and how to study a snowcover" (PDF). Canadian Field-Naturalist. 119 (1): 118–128. doi:10.22621/cfn.v119i1.90.

- ^ Kaplan, Larry (2003). "Inuit Snow Terms: How Many and What Does It Mean?". Building Capacity in Arctic Societies: Dynamics and Shifting Perspectives. Proceedings from the 2nd IPSSAS Seminar. Nunavut, Canada: May 26-June 6, 2003. Montreal: Alaska Native Language Center. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ Environment, Canada (10 March 2010). "Skywatchers weather glossary". aem. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ National Weather Service, NOAA. "Glossary: Blizzard". w1.weather.gov. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Ahrens, C. Donald (2007). Meteorology today: an introduction to weather, climate, and the environment (8th ed.). Belmont, Calif.: Thomson/Brooks/Cole. pp. 298–300, 352. ISBN 978-0-495-01162-0. OCLC 66911677.

- ^ "Lake-effect snow - AMS Glossary". glossary.ametsoc.org. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ National Weather Service, NOAA. "Glossary - Lake effect snow". w1.weather.gov. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ National Weather Service, NOAA. "Glossary - Snow flurry". w1.weather.gov. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ National Weather Service, NOAA. "Glossary - Snow squall". w1.weather.gov. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Thundersnow - AMS Glossary". glossary.ametsoc.org. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "National Weather Service Expanded Winter Weather Terminology". www.weather.gov. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Frozen precipitation - AMS Glossary". glossary.ametsoc.org. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Snow - AMS Glossary". glossary.ametsoc.org. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Ice crystal - AMS Glossary". glossary.ametsoc.org. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ National Weather Service, NOAA. "Glossary - ice crystal". w1.weather.gov. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Ice pellets - AMS Glossary". glossary.ametsoc.org. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ Knight, C.; Knight, N. (1973). Snow crystals. Scientific American, vol. 228, no. 1, pp. 100–107.

- ^ "Snow grains - AMS Glossary". glossary.ametsoc.org. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Snow pellets - AMS Glossary". glossary.ametsoc.org. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ Warren, Israel Perkins (1863). Snowflakes: a chapter from the book of nature. Boston: American Tract Society. p. 164. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ Bishop, Michael P.; Björnsson, Helgi; Haeberli, Wilfried; Oerlemans, Johannes; Shroder, John F.; Tranter, Martyn (2011). Singh, Vijay P.; Singh, Pratap; Haritashya, Umesh K. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Snow, Ice and Glaciers. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1253. ISBN 978-90-481-2641-5.

- ^ Magono, Choji; Lee, Chung Woo (1966). "Meteorological Classification of Natural Snow Crystals". Journal of the Faculty of Science. 7. 3 (4) (Geophysics ed.). Hokkaido: 321–335. hdl:2115/8672.

- ^ a b c d e Fierz, C.; Armstrong, R.L.; Durand, Y.; Etchevers, P.; Greene, E.; et al. (2009), The International Classification for Seasonal Snow on the Ground (PDF), IHP-VII Technical Documents in Hydrology, vol. 83, Paris: UNESCO, p. 80, archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2016, retrieved 25 November 2016

- ^ "Snow crust - AMS Glossary". glossary.ametsoc.org. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ Tejada-Flores, Lito (December 1982). Become a backcountry expert. Backpacker. pp. 28–34.

- ^ a b c d e The Mountaineers (25 August 2010). Eng, Ronald C. (ed.). Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills. Seattle: Mountaineers Books. pp. 540–8. ISBN 978-1-59485-408-8.

- ^ Lopez, Barry; Gwartney, Debra (14 April 2011). Home Ground: Language for an American Landscape. Trinity University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-59534-088-7.

- ^ Avery, Martin (2 February 2016). Canada, I Love You: The Canadian Dream. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-329-87486-2.

- ^ Hince, Bernadette (2000). The Antarctic Dictionary: A Complete Guide to Antarctic English. Csiro Publishing. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-9577471-1-1.

- ^ Leonard, K. C.; Tremblay, B. (December 2006). "Depositional origin of snow sastrugi". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2006: C21C–1170. Bibcode:2006AGUFM.C21C1170L. #C21C-1170.

- ^ Bartelt, P.; Adams, E.; Christen, M.; Sack, R.; Sato, A. (15 June 2004). Snow Engineering V: Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Snow Engineering, 5-8 July 2004, Davos, Switzerland. CRC Press. pp. 193–8. ISBN 978-90-5809-634-0.

- ^ a b Daffern, Tony (14 September 2009). Backcountry Avalanche Safety: Skiers, Climbers, Boarders, Snowshoers. Rocky Mountain Books Ltd. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-897522-54-7.

- ^ a b Paterson, W. S. B. (31 January 2017). The Physics of Glaciers. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4832-9373-8.

- ^ "Geol 33 Environmental Geomorphology". Hofstra University. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ Lliboutry, L. (1954b). "The origin of penitentes". Journal of Glaciology. 2 (15): 331–338. Bibcode:1954JGlac...2..331L. doi:10.1017/S0022143000025181.

- ^ Knight, Peter (13 May 2013). Glaciers. Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-134-98224-0.

- ^ T. Kameda (2007). "Discovery and reunion with yukimarimo" (PDF). Seppyo (Journal of Japanese Society of Snow and Ice). 69 (3): 403–407. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Staff (January 1975). Handy Facts. Ski. p. 42.

- ^ Delaney, Brian (January 1998). Crud: Stay light and centered on the edge. Snow Country. p. 106.

- ^ Yankielun, Norbert (2007). How to build an igloo: And other snow shelters. W. W. Norton & Company.

- ^ Yacenda, John; Ross, Tim (1998). High-performance Skiing. Human Kinetics. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-0-88011-713-5.

- ^ Higgs, Liz Curtis (1998). Help! I'm Laughing and I Can't Get Up. HarperCollins Christian Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4185-5875-8.

- ^ William E. Williams; Holly L. Gorton & Thomas C. Vogelmann (21 January 2003). "Surface gas-exchange processes of snow algae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (2): 562–566. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100..562W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0235560100. PMC 141035. PMID 12518048.

- ^ Regier, Terry; Carstensen, Alexandra; Kemp, Charles (13 April 2016). "Languages Support Efficient Communication about the Environment: Words for Snow Revisited". PLOS ONE. 11 (4) e0151138. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1151138R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0151138. PMC 4830456. PMID 27073981.

- ^ Brune, Vanessa (18 March 2018). "Snow in Kuusamo or Why the Finnish language has countless words for snow". Nordic Wanders: Wandering Scandinavia & the Nordics. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Lella Erludóttir (13 September 2020). "Icelandic oddities: 85 words for snow". Hey Iceland. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Ertesvåg, Ivar S. (19 November 1998). "Norske ord for/om snø" [Norwegian words for/about snow] (in Norwegian). Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Trube, L.L. (1978). "The Various Russian Words for Snowstorm". Soviet Geography. 19 (8): 572–575. doi:10.1080/00385417.1978.10640252.

- ^ Kazimianec, Jelena (2013). "Snow in the Russian Language Picture of the World". Respectus Philologicus. 24 (29): 121–130. doi:10.15388/RESPECTUS.2013.24.29.10.

- ^ Shipley, Neil (28 February 2018). "50 Words for Snow!". Watching the Swedes. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Magga, Ole Henrik (March 2006). "Diversity in Saami terminology for reindeer, snow, and ice". International Social Science Journal. 58 (187): 25–34. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2451.2006.00594.x.

- ^ Berit, Inga; Öje, Danell (2013). "Traditional ecological knowledge among Sami reindeer herders in northern Sweden about vascular plants grazed by reindeer". Rangifer. 32 (1): 1–17. doi:10.7557/2.32.1.2233.

- ^ a b Robson, David. "Are there really 50 Eskimo words for snow?". New Scientist. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ Krupnik, Igor; Müller-Wille, Ludger (2010), "Franz Boas and Inuktitut Terminology for Ice and Snow: From the Emergence of the Field to the "Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax"", in Krupnik, Igor; Aporta, Claudio; Gearheard, Shari; Laidler, Gita J.; Holm, Lene Kielsen (eds.), SIKU: Knowing Our Ice: Documenting Inuit Sea Ice Knowledge and Use, Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media, pp. 377–99, ISBN 978-90-481-8587-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Why and How to Study a Snowcover – contains an extensive taxonomy of show terminology borrowed from Inuit and some other languages

- Fierz, C., Armstrong, R.L., Durand, Y., Etchevers, P., Greene, E., McClung, D.M., Nishimura, K., Satyawali, P.K. and Sokratov, S.A.; The International Classification for Seasonal Snow on the Ground. IHP-VII Technical Documents in Hydrology N°83, IACS Contribution N°1, UNESCO-IHP, Paris, 2009.