Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Iñupiaq language

View on Wikipedia| Iñupiaq | |

|---|---|

| Uqausiq/Uqausriq Iñupiatun, Qanġuziq/Qaġnuziq/Qanġusiq Inupiatun | |

| Native to | United States, formerly Russia; Northwest Territories of Canada |

| Region | Alaska; formerly Big Diomede Island |

| Ethnicity | 20,709 Iñupiat (2015) |

Native speakers | 1,250 fully fluent speakers (2023)[1] |

Early forms | |

| Latin (Iñupiaq alphabet) Iñupiaq Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Alaska,[2] Northwest Territories (as Uummarmiutun dialect) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ik |

| ISO 639-2 | ipk |

| ISO 639-3 | ipk – inclusive codeIndividual codes: esi – North Alaskan Iñupiatunesk – Northwest Alaska Iñupiatun |

| Glottolog | inup1234 |

| ELP | Inupiaq |

| |

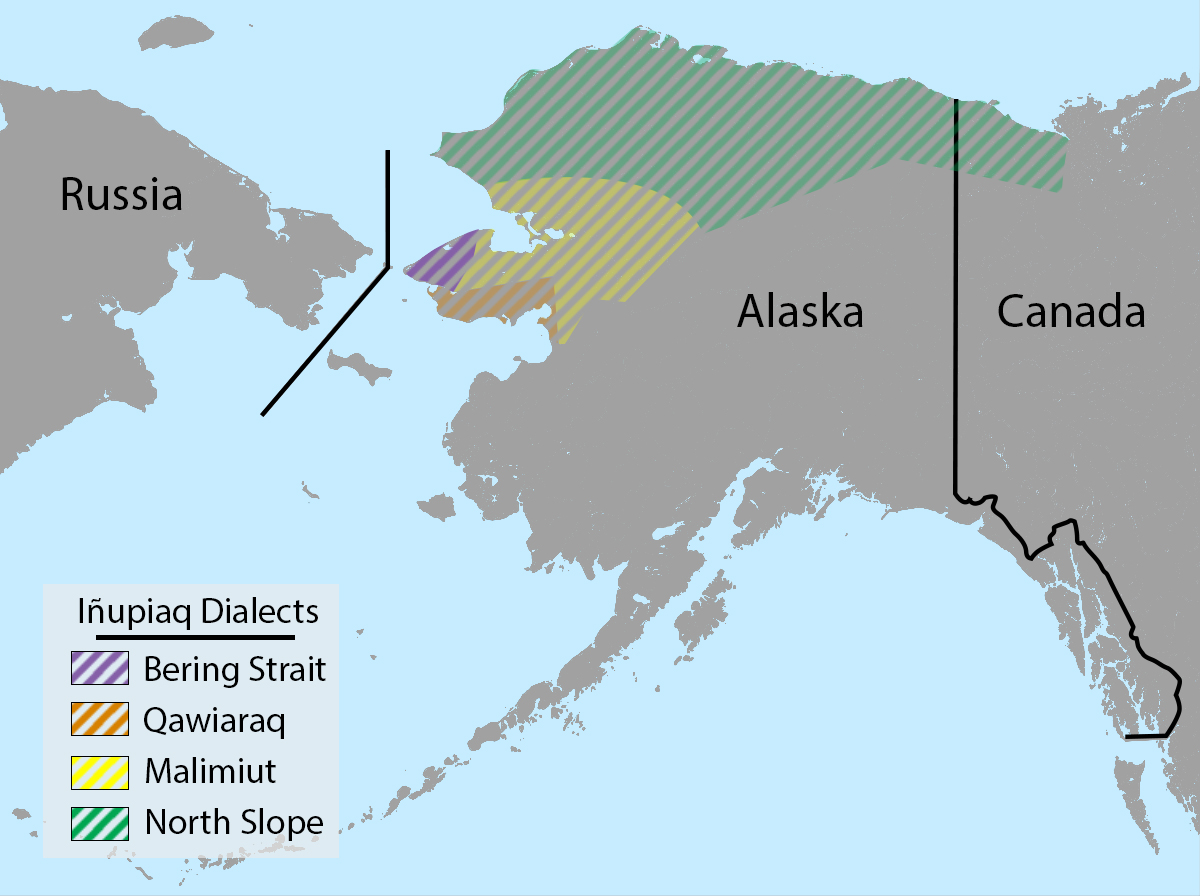

Iñupiaq dialects and speech communities | |

| iñuk / nuna "person" / "land" | |

|---|---|

| Person | Iñupiaq Dual: Iñupiak |

| People | Iñupiat |

| Language | Iñupiatun |

| Country | Iñupiat Nunaat |

Iñupiaq or Inupiaq (/ɪ.ˈnuː.pi.æk/ ih-NOO-pee-ak, Inupiaq: [iɲupiaq]), also known as Iñupiat, Inupiat (/ɪ.ˈnuː.pi.æt/ ih-NOO-pee-at), Iñupiatun or Alaskan Inuit, is an Inuit language, or perhaps group of languages, spoken by the Iñupiat people in northern and northwestern Alaska, as well as a small adjacent part of the Northwest Territories of Canada. The Iñupiat language is a member of the Inuit–Yupik–Unangan language family, and is closely related and, to varying degrees, mutually intelligible with other Inuit languages of Canada and Greenland. There are roughly 2,000 speakers.[3] Iñupiaq is considered to be a threatened language, with most speakers at or above the age of 40.[4] Iñupiaq is an official language of the State of Alaska, along with several other indigenous languages.[5]

The major varieties of the Iñupiaq language are the North Slope Iñupiaq and Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq dialects.

The Iñupiaq language has been in decline since contact with English in the late 19th century. American territorial acquisition and the legacy of boarding schools have created a situation today where a small minority of Iñupiat speak the Iñupiaq language. There is, however, revitalization work underway today in several communities.

History

[edit]The Iñupiaq language is an Inuit language, the ancestors of which may have been spoken in the northern regions of Alaska for as long as 5,000 years. Between 1,000 and 800 years ago, Inuit migrated east from Alaska to Canada and Greenland, eventually occupying the entire Arctic coast and much of the surrounding inland areas. The Iñupiaq dialects are the most conservative forms of the Inuit language, with less linguistic change than the other Inuit languages.[citation needed]

In the mid to late 19th century, Russian, British, and American colonists made contact with Iñupiat people. In 1885, the American territorial government appointed Rev. Sheldon Jackson as General Agent of Education.[6] Under his administration, Iñupiat people (and all Alaska Natives) were educated in English-only environments, forbidding the use of Iñupiaq and other indigenous languages of Alaska. After decades of English-only education, with strict punishment if heard speaking Iñupiaq, after the 1970s, most Iñupiat did not pass the Iñupiaq language on to their children, for fear of them being punished for speaking their language.

In 1972, the Alaska Legislature passed legislation mandating that if "a [school is attended] by at least 15 pupils whose primary language is other than English, [then the school] shall have at least one teacher who is fluent in the native language".[7]

Today, the University of Alaska Fairbanks offers bachelor's degrees in Iñupiaq language and culture, while a preschool/kindergarten-level Iñupiaq immersion school named Nikaitchuat Iḷisaġviat teaches grades PreK–1st grade in Kotzebue.

In 2014, Iñupiaq became an official language of the State of Alaska, alongside English and nineteen other indigenous languages.[5] In the same year, Iñupiat linguist and educator Edna Ahgeak MacLean published an Iñupiaq - English grammar and dictionary with over 19,000 entries. An online version was later released by her.[8]

In 2018, Facebook added Iñupiaq as a language option on their website.[9] In 2022, an Iñupiaq version of Wordle was created.[10][11]

Dialects

[edit]There are four main dialect divisions and these can be organized within two larger dialect collections:[12]

- Iñupiaq

- Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq is spoken on the Seward Peninsula. It has a possible Yupik substrate and is divergent from other Inuit languages.

- Qawiaraq

- Bering Strait

- Northern Alaskan Iñupiaq is spoken from the Northwest Arctic and North Slope regions of Alaska to the Mackenzie Delta in Northwest Territories, Canada.

- Malimiut

- North Slope Iñupiaq

- Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq is spoken on the Seward Peninsula. It has a possible Yupik substrate and is divergent from other Inuit languages.

| Dialect collection[12][13] | Dialect[12][13] | Subdialect[12][13] | Tribal nation(s) | Populated areas[13] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq | Bering Strait | Diomede | Iŋalit | Little Diomede Island, Big Diomede Island until the late 1940s |

| Wales | Kiŋikmiut, Tapqaġmiut | Wales, Shishmaref, Brevig Mission | ||

| King Island | Ugiuvaŋmiut | King Island until the early 1960s, Nome | ||

| Qawiaraq | Teller | Siñiġaġmiut, Qawiaraġmiut | Teller, Shaktoolik | |

| Fish River | Iġałuiŋmiut | White Mountain, Golovin | ||

| Northern Alaskan Iñupiaq | Malimiutun | Kobuk | Kuuŋmiut, Kiitaaŋmiut [Kiitaaġmiut], Siilim Kaŋianiġmiut, Nuurviŋmiut, Kuuvaum Kaŋiaġmiut, Akuniġmiut, Nuataaġmiut, Napaaqtuġmiut, Kivalliñiġmiut[14] | Kobuk River Valley, Selawik |

| Coastal | Pittaġmiut, Kaŋiġmiut, Qikiqtaġruŋmiut[14] | Kotzebue, Noatak | ||

| North Slope / Siḷaliñiġmiutun | Common North Slope | Utuqqaġmiut, Siliñaġmiut [Kukparuŋmiut and Kuuŋmiut], Kakligmiut [Sitarumiut, Utqiaġvigmiut and Nuvugmiut], Kuulugruaġmiut, Ikpikpagmiut, Kuukpigmiut [Kañianermiut, Killinermiut and Kagmalirmiut][14][15] | ||

| Point Hope[16] | Tikiġaġmiut | Point Hope[16] | ||

| Point Barrow | Nuvuŋmiut | |||

| Anaktuvuk Pass | Nunamiut | Anaktuvuk Pass | ||

| Uummarmiutun (Uummaġmiutun) | Uummarmiut (Uummaġmiut) | Aklavik (Canada), Inuvik (Canada) |

Extra geographical information:

Bering Strait dialect:

The Native population of the Big Diomede Island was moved to the Siberian mainland after World War II. The following generation of the population spoke Central Siberian Yupik or Russian.[13] The entire population of King Island moved to Nome in the early 1960s.[13] The Bering Strait dialect might also be spoken in Teller on the Seward Peninsula.[16]

Qawiaraq dialect:

A dialect of Qawiaraq is spoken in Nome.[16][13] A dialect of Qawariaq may also be spoken in Koyuk,[13] Mary's Igloo, Council, and Elim.[16] The Teller sub-dialect may be spoken in Unalakleet.[16][13]

Malimiutun dialect:

Both sub-dialects can be found in Buckland, Koyuk, Shaktoolik, and Unalakleet.[16][13] A dialect of Malimiutun may be spoken in Deering, Kiana, Noorvik, Shungnak, and Ambler.[16] The Malimiutun sub-dialects have also been classified as "Southern Malimiut" (found in Koyuk, Shaktoolik, and Unalakleet) and "Northern Malimiut" found in "other villages".[16]

North Slope dialect:

Common North Slope is "a mix of the various speech forms formerly used in the area".[13] The Point Barrow dialect was "spoken only by a few elders" in 2010.[13] A dialect of North Slope is also spoken in Kivalina, Point Lay, Wainwright, Atqasuk, Utqiaġvik, Nuiqsut, and Barter Island.[16]

Phonology

[edit]Iñupiaq dialects differ widely between consonants used. However, consonant clusters of more than two consonants in a row do not occur. A word may not begin nor end with a consonant cluster.[16]

All Iñupiaq dialects have three basic vowel qualities: /a i u/.[16][13] There is currently no instrumental work to determine what allophones may be linked to these vowels. All three vowels can be long or short, giving rise to a system of six phonemic vowels /a aː i iː u uː/. Long vowels are represented by double letters in the orthography: ⟨aa⟩, ⟨ii⟩, ⟨uu⟩.[16] The following diphthongs occur: /ai ia au ua iu ui/.[16][17] No more than two vowels occur in a sequence in Iñupiaq.[16]

The Bering strait dialect has a fourth vowel /e/, which preserves the fourth proto-Eskimo vowel reconstructed as */ə/.[16][13] In the other dialects, proto-Eskimo */e/ has merged with the closed front vowel /i/. The merged /i/ is referred to as the "strong /i/", which causes palatalization when preceding consonant clusters in the North Slope dialect (see section on palatalization below). The other /i/ is referred to as "the weak /i/". Weak and strong /i/s are not differentiated in orthography,[16] making it impossible to tell which ⟨i⟩ represents palatalization "short of looking at other processes which depend on the distinction between two i's or else examining data from other Eskimo languages".[18] However, it can be assumed that, within a word, if a palatal consonant is preceded by an ⟨i⟩, it is strong. If an alveolar consonant is preceded by an ⟨i⟩, it is weak.[18]

Words begin with a stop (with the exception of the palatal stop /c/), the fricative /s/, nasals /m n/, with a vowel, or the semivowel /j/. Loanwords, proper names, and exclamations may begin with any segment in both the Seward Peninsula dialects and the North Slope dialects.[16] In the Uummarmiutun dialect words can also begin with /h/. For example, the word for "ear" in North Slope and Little Diomede Island dialects is siun whereas in Uummarmiutun it is hiun.

A word may end in any nasal sound (except for the /ɴ/ found in North Slope), in the stops /t k q/ or in a vowel. In the North Slope dialect if a word ends with an m, and the next word begins with a stop, the m is pronounced /p/, as in aġnam tupiŋa, pronounced /aʁnap tupiŋa/[16]

Very little information of the prosody of Iñupiaq has been collected. However, "fundamental frequency (Hz), intensity (dB), loudness (sones), and spectral tilt (phons - dB) may be important" in Malimiutun.[19] Likewise, "duration is not likely to be important in Malimiut Iñupiaq stress/syllable prominence".[19]

North Slope Iñupiaq

[edit]For North Slope Iñupiaq[12][16][20]

| Labial | Alveolar | Retroflex / Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ɴ | ||

| Stops | p | t | c [19] | k | q | ʔ[a] | |

| Fricatives | voiceless | f | s | ʂ | x | χ | h |

| voiced | v | ʐ[b] | ɣ | ʁ | |||

| Lateral | voiceless | ɬ | 𝼆[c] | ||||

| voiced | l | ʎ | |||||

| Approximant | j | ||||||

The voiceless stops /p/ /t/ /k/ and /q/ are not aspirated.[16] This may or may not be true for other dialects as well.

/c/ is derived from a palatalized and unreleased /t/.[16]

Assimilation

[edit]Source:[16]

Two consonants cannot appear together unless they share the manner of articulation (in this case treating the lateral and approximant consonants as fricatives). The only exception to this rule is having a voiced fricative consonant appear with a nasal consonant. Since all stops in North Slope are voiceless, a lot of needed assimilation arises from having to assimilate a voiceless stop to a voiced consonant.

This process is realized by assimilating the first consonant in the cluster to a consonant that: 1) has the same (or closest possible) area of articulation as the consonant being assimilated to; and 2) has the same manner of articulation as the second consonant that it is assimilating to. If the second consonant is a lateral or approximant, the first consonant will assimilate to a lateral or approximant if possible. If not the first consonant will assimilate to a fricative. Therefore:

| IPA | Example |

|---|---|

| /kn/ → /ɣn/ or → /ŋn/ |

Kamik "to put boots on" + + niaq "will" + + te "he" → → kamigniaqtuq or kamiŋniaqtuq he will put the boots on |

| /qn/ → /ʁn/ or → /ɴ/ * |

iḷisaq "to study" + + niaq "will" + + tuq "he" → → iḷisaġniaqtuq he will study |

| /tn/ → /nn/ | aqpat "to run" + + niaq "will" + + tuq "he" → → aqpanniaqtuq he will run |

| /tm/ → /nm/ | makit "to stand up" + + man "when he" → → makinman When he stood up |

| /tɬ/ → /ɬɬ/ | makit "to stand" + + łuni "by ---ing" → → makiłłuni standing up, he ... |

- * The sound /ɴ/ is not represented in the orthography. Therefore the spelling ġn can be pronounced as /ʁn/ or /ɴn/. In both examples 1 and 2, since voiced fricatives can appear with nasal consonants, both consonant clusters are possible.

The stops /t̚ʲ/ and /t/ do not have a corresponding voiced fricative, therefore they will assimilate to the closest possible area of articulation. In this case, the /t̚ʲ/ will assimilate to the voiced approximant /j/. The /t/ will assimilate into a /ʐ/. Therefore:

| IPA | Example |

|---|---|

| /t̚ʲɣ/ → /jɣ/ | siksriit "squirrels" + + guuq "it is said that" → → siksriiyguuq it is said that squirrels |

| /tv/ → /ʐv/ | aqpat "to run" + + vik "place" → → aqparvik race track |

(In the first example above note that <sr> denotes a single consonant, as shown in the alphabet section below, so the constraint of at most two consonants in a cluster, as mentioned above, is not violated.)

In the case of the second consonant being a lateral, the lateral will again be treated as a fricative. Therefore:

| IPA | Example |

|---|---|

| /ml/ → /ml/ or → /vl/ |

aġnam "(of) the woman" + + lu "and" → → aġnamlu or aġnavlu and (of) the woman |

| /nl/ → /nl/ or → /ll/ |

aŋun "the man" + + lu "and" → → aŋunlu or aŋullu and the man |

Since voiced fricatives can appear with nasal consonants, both consonant clusters are possible.

The sounds /f/ /x/ and /χ/ are not represented in the orthography (unless they occur alone between vowels). Therefore, like the /ɴn/ example shown above, assimilation still occurs while the spelling remains the same. Therefore:

| IPA (pronunciation) | Example |

|---|---|

| /qɬ/ → /χɬ/ | miqłiqtuq child |

| /kʂ/ → /xʂ/ | siksrik squirrel |

| /vs/ → /fs/ | tavsi belt |

These general features of assimilation are not shared with Uummarmiut, Malimiutun, or the Seward Peninsula dialects. Malimiutun and the Seward Peninsula dialects "preserve voiceless stops (k, p, q, t) when they are etymological (i.e. when they belong to the original word-base)".[13] Compare:

| North Slope | Malimiutun | Seward Peninsula dialects | Uummarmiut | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nivliqsuq | nipliqsuq | nivliraqtuq | makes a sound | |

| igniq | ikniq | ikniq | fire | |

| annuġaak | atnuġaak | atar̂aaq | garment |

Palatalization

[edit]Source:[16]

The following patterns of palatalization can occur in North Slope Iñupiaq: /t/ → /t̚ʲ/, /tʃ/ or /s/; /ɬ/ → /ʎ̥/; /l/ → /ʎ/; and /n/ → /ɲ/. Palatalization only occurs when one of these four alveolars is preceded by a strong i. Compare:

| Type of I | Example |

|---|---|

| strong | qimmiq /qimːiq/ dog → → → qimmit /qimːit̚ʲ/ dogs |

| weak | tumi /tumi/ footprint → → → tumit /tumit/ footprints |

| strong | iġġi /iʁːi/ mountain → → → iġġiḷu /iʁːiʎu/ and a mountain |

| weak | tumi /tumi/ footprint → → → tumilu /tumilu/ and a footprint |

- Please note that the sound /t̚ʲ/ does not have its own letter, and is simply spelled with a T t. The IPA transcription of the above vowels may be incorrect.

If a t that precedes a vowel is palatalized, it will become an /s/. The strong i affects the entire consonant cluster, palatalizing all consonants that can be palatalized within the cluster. Therefore:

| Type of I | Example |

|---|---|

| strong | qimmiq /qimmiq/ dog + + + tigun /tiɣun/ amongst the plural things → → → qimmisigun /qimːisiɣun/ amongst, in the midst of dogs |

| strong | puqik /puqik/ to be smart + + + tuq /tuq/ she/he/it → → → puqiksuq /puqiksuq/ she/he/it is smart |

- Note in the first example, due to the nature of the suffix, the /q/ is dropped. Like the first set of examples, the IPA transcriptions of above vowels may be incorrect.

If a strong i precedes geminate consonant, the entire elongated consonant becomes palatalized. For Example: niġḷḷaturuq and tikiññiaqtuq.

Further strong versus weak i processes

[edit]Source:[16]

The strong i can be paired with a vowel. The weak i on the other hand cannot.[18] The weak i will become an a if it is paired with another vowel, or if the consonant before the i becomes geminate. This rule may or may not apply to other dialects. Therefore:

| Type of I | Example |

|---|---|

| weak | tumi /tumi/ footprint → → → tumaa /tumaː/ her/his footprint |

| strong | qimmiq /qimːiq/ dog → → → qimmia /qimːia/ her/his dog |

| weak | kamik /kamik/ boot → → → kammak /kamːak/ two boots |

Like the first two sets of examples, the IPA transcriptions of above vowels may not be correct.

Uummarmiutun sub-dialect

[edit]For the Uummarmiutun sub-dialect:[17]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Retroflex | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||||

| Stops | voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k | q | ʔ[a] | |

| voiced | dʒ | |||||||

| Fricatives | voiceless | f | x | χ | h | |||

| voiced | v | ʐ | ɣ | ʁ | ||||

| Lateral | voiceless | ɬ | ||||||

| voiced | l | |||||||

| Approximant | j | |||||||

- ^ Ambiguities: This sound might exist in the Uummarmiutun sub dialect.

Phonological rules

[edit]The following are the phonological rules:[17] The /f/ is always found as a geminate.

The /j/ cannot be geminated, and is always found between vowels or preceded by /v/. In rare cases it can be found at the beginning of a word.

The /h/ is never geminate, and can appear as the first letter of the word, between vowels, or preceded by /k/ /ɬ/ or /q/.

The /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ are always geminate or preceded by a /t/.

The /ʐ/ can appear between vowels, preceded by consonants /ɣ/ /k/ /q/ /ʁ/ /t/ or /v/, or it can be followed by /ɣ/, /v/, /ʁ/.

Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq

[edit]For Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq:[12]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Retroflex | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | |||||

| Stops | voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k | q | ʔ | |

| voiced | b | |||||||

| Fricatives | voiceless | s | ʂ | h | ||||

| voiced | v | z | ʐ | ɣ | ʁ | |||

| Lateral | voiceless | ɬ | ||||||

| voiced | l | |||||||

| Approximant | w | j | ɻ | |||||

Unlike the other Iñupiaq dialects, the Seward Peninsula dialect has a mid central vowel e (see the beginning of the phonology section for more information).

Gemination

[edit]In North Slope Iñupiaq, all consonants represented by orthography can be geminated, except for the sounds /tʃ/ /s/ /h/ and /ʂ/.[16] Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq (using vocabulary from the Little Diomede Island as a representative sample) likewise can have all consonants represented by orthography appear as geminates, except for /b/ /h/ /ŋ/ /ʂ/ /w/ /z/ and /ʐ/. Gemination is caused by suffixes being added to a consonant, so that the consonant is found between two vowels.[16]

Writing systems

[edit]Iñupiaq was first written when explorers first arrived in Alaska and began recording words in the native languages. They wrote by adapting the letters of their own language to writing the sounds they were recording. Spelling was often inconsistent, since the writers invented it as they wrote. Unfamiliar sounds were often confused with other sounds, so that, for example, 'q' was often not distinguished from 'k' and long consonants or vowels were not distinguished from short ones.

Along with the Alaskan and Siberian Yupik, the Iñupiat eventually adopted the Latin script that Moravian missionaries developed in Greenland and Labrador. Native Alaskans also developed a system of pictographs,[which?] which, however, died with its creators.[21]

In 1946, Roy Ahmaogak, an Iñupiaq Presbyterian minister from Utqiaġvik, worked with Eugene Nida, a member of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, to develop the current Iñupiaq alphabet based on the Latin script. Although some changes have been made since its origin—most notably the change from 'ḳ' to 'q'—the essential system was accurate and is still in use.

| A a | Ch ch | G g | Ġ ġ | H h | I i | K k | L l | Ḷ ḷ | Ł ł | Ł̣ ł̣ | M m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | cha | ga | ġa | ha | i | ka | la | ḷa | ła | ł̣a | ma |

| /a/ | /tʃ/ | /ɣ/ | /ʁ/ | /h/ | /i/ | /k/ | /l/ | /ʎ/ | /ɬ/ | /𝼆/ | /m/ |

| N n | Ñ ñ | Ŋ ŋ | P p | Q q | R r | S s | Sr sr | T t | U u | V v | Y y |

| na | ña | ŋa | pa | qa | ra | sa | sra | ta | u | va | ya |

| /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | /p/ | /q/ | /ɹ/ | /s/ | /ʂ/ | /t/ | /u/ | /v/ | /j/ |

Extra letter for Kobuk dialect: ʼ /ʔ/

| A a | B b | G g | Ġ ġ | H h | I i | K k | L l | Ł ł | M m | N n | Ŋ ŋ | P p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | ba | ga | ġa | ha | i | ka | la | ła | ma | na | ŋa | pa |

| /a/ | /b/ | /ɣ/ | /ʁ/ | /h/ | /i/ | /k/ | /l/ | /ɬ/ | /m/ | /n/ | /ŋ/ | /p/ |

| Q q | R r | S s | Sr sr | T t | U u | V v | W w | Y y | Z z | Zr zr | ʼ | |

| qa | ra | sa | sra | ta | u | va | wa | ya | za | zra | ||

| /q/ | /ɹ/ | /s/ | /ʂ/ | /t/ | /u/ | /v/ | /w/ | /j/ | /z/ | /ʐ/ | /ʔ/ |

Extra letters for specific dialects:

| A a | Ch ch | F f | G g | H h | Dj dj | I i | K k | L l | Ł ł | M m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | cha | fa | ga | ha | dja | i | ka | la | ła | ma |

| /a/ | /tʃ/ | /f/ | /ɣ/ | /h/ | /dʒ/ | /i/ | /k/ | /l/ | /ɬ/ | /m/ |

| N n | Ñ ñ | Ng ng | P p | Q q | R r | R̂ r̂ | T t | U u | V v | Y y |

| na | ña | ŋa | pa | qa | ra | r̂a | ta | u | va | ya |

| /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | /p/ | /q/ | /ʁ/ | /ʐ/ | /t/ | /u/ | /v/ | /j/ |

Morphosyntax

[edit]Due to the number of dialects and complexity of Iñupiaq morphosyntax, the following section discusses Malimiutun morphosyntax as a representative. Any examples from other dialects will be marked as such.

Iñupiaq is a polysynthetic language, meaning that words can be extremely long, consisting of one of three stems (verb stem, noun stem, and demonstrative stem) along with one or more of three endings (postbases, (grammatical) endings, and enclitics).[16] The stem gives meaning to the word, whereas endings give information regarding case, mood, tense, person, plurality, etc. The stem can appear as simple (having no postbases) or complex (having one or more postbases). In Iñupiaq a "postbase serves somewhat the same functions that adverbs, adjectives, prefixes, and suffixes do in English" along with marking various types of tenses.[16] There are six word classes in Malimiut Inñupiaq: nouns (see Nominal Morphology), verbs (see Verbal Morphology), adverbs, pronouns, conjunctions, and interjections. All demonstratives are classified as either adverbs or pronouns.[19]

Nominal morphology

[edit]The Iñupiaq category of number distinguishes singular, dual, and plural. The language works on an Ergative–Absolutive system, where nouns are inflected for number, several cases, and possession.[16] Iñupiaq (Malimiutun) has nine cases, two core cases (ergative and absolutive) and seven oblique cases (instrumental, allative, ablative, locative, perlative, similative and vocative).[19] North Slope Iñupiaq does not have the vocative case.[16] Iñupiaq does not have a category of gender and articles.[citation needed]

Iñupiaq nouns can likewise be classified by Wolf A. Seiler's seven noun classes.[19][23] These noun classes are "based on morphological behavior. [They] ... have no semantic basis but are useful for case formation ... stems of various classes interact with suffixes differently".[19]

Due to the nature of the morphology, a single case can take on up to 12 endings (ignoring the fact that realization of these endings can change depending on noun class). For example, the possessed ergative ending for a class 1a noun can take on the endings: -ma, ‑mnuk, ‑pta, ‑vich, ‑ptik, -psi, -mi, -mik, -miŋ, -ŋan, -ŋaknik, and ‑ŋata. Therefore, only general features will be described below. For an extensive list on case endings, please see Seiler 2012, Appendix 4, 6, and 7.[23]

Absolutive case/noun stems

[edit]The subject of an intransitive sentence or the object of a transitive sentence take on the absolutive case. This case is likewise used to mark the basic form of a noun. Therefore, all the singular, dual, and plural absolutive forms serve as stems for the other oblique cases.[16] The following chart is verified of both Malimiutun and North Slope Iñupiaq.

| Endings | |

|---|---|

| singular | -q, -k, -n, or any vowel |

| dual | -k |

| plural | -t |

If the singular absolutive form ends with -n, it has the underlying form of -ti /tə/. This form will show in the absolutive dual and plural forms. Therefore:

tiŋmisuun

airplane

→

tiŋmisuutik

two airplanes

&

tiŋmisuutit

multiple airplanes

Regarding nouns that have an underlying /ə/ (weak i), the i will change to an a and the previous consonant will be geminated in the dual form. Therefore:

Kamik

boot

→

kammak

two boots

If the singular form of the noun ends with -k, the preceding vowel will be elongated. Therefore:

savik

knife

→

saviik

two knives

On occasion, the consonant preceding the final vowel is also geminated, though exact phonological reasoning is unclear.[19]

Ergative case

[edit]The ergative case is often referred to as the Relative Case in Iñupiaq sources.[16] This case marks the subject of a transitive sentence or a genitive (possessive) noun phrase. For non-possessed noun phrases, the noun is marked only if it is a third person singular. The unmarked nouns leave ambiguity as to who/what is the subject and object. This can be resolved only through context.[16][19] Possessed noun phrases and noun phrases expressing genitive are marked in ergative for all persons.[19]

| Endings | Allophones |

|---|---|

| -m | -um, -im |

This suffix applies to all singular unpossessed nouns in the ergative case.

| Example | English |

|---|---|

| aŋun → aŋutim | man → man (ergative) |

| aŋatchiaq → aŋatchiaŋma | uncle → my two uncles (ergative) |

Please note the underlying /tə/ form in the first example.

Instrumental case

[edit]This case is also referred to as the modalis case. This case has a wide range of uses described below:

| Usage of instrumental[19] | Example |

|---|---|

| Marks nouns that are means by which the subject achieves something (see instrumental) | Aŋuniaqtim hunter.ERG aġviġluaq gray wale-ABS tuqutkaa kill-IND-3SG.SBJ-3SG.OBJ nauligamik. harpoon-INS

(using it as a tool to) The hunter killed the gray whale with a harpoon. |

| Marks the apparent patient (grammatical object upon which the action was carried out) of syntactically intransitive verbs | Miñułiqtugut paint-IND-3SG.OBJ umiamik. boat-INS

(having the previous verb being done to it) We're painting a boat. |

| Marks information new to the narrative (when the noun is first mentioned in a narrative)

Marks indefinite objects of some transitive verbs |

Tuyuġaat send-IND-3PL.SBJ-3SG.OBJ tuyuutimik. letter-INS

(new piece of information) They sent him a letter. |

| Marks the specification of a noun's meaning to incorporate the meaning of another noun (without incorporating both nouns into a single word) (Modalis of specification)[16] | Niġiqaqtuguk food—have-IND-1DU.SBJ tuttumik. caribou-INS

(specifying that the caribou is food by referring to the previous noun) We (dual) have (food) caribou for food. |

Qavsiñik how many-INS paniqaqpit? daughter—have

(of the following noun) How many daughters do you have? |

| Endings | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| singular | -mik | Kamik boot → → kamiŋmik (with a) boot |

| dual | [dual absolutive stem] -nik | kammak (two) boots → → kammaŋnik (with two) boots |

| plural | [singular absolutive stem] -nik | kamik boot → → kamiŋnik (with multiple) boots |

Since the ending is the same for both dual and plural, different stems are used. In all the examples the k is assimilated to an ŋ.

Allative case

[edit]The allative case is also referred to as the terminalis case. The uses of this case are described below:[19]

| Usage of Allative[19] | Example |

|---|---|

| Used to signify motion or an action directed towards a goal[16] | Qaliŋaum Qaliŋak-ERG quppiġaaq coat-ABS atauksritchaa lend-IND-3SG.SBJ-3SG.OBJ Nauyamun. Nauyaq-ALL

(towards his direction/to him) Qaliŋak lent a coat to Nauyaq |

Isiqtuq enter-IND-3SG iglumun. house-ALL

(into) He went into the house | |

| Signifies that the statement is for the purpose of the marked noun | Niġiqpaŋmun feast-ALL niqiłiuġñiaqtugut. prepare.a.meal-FUT-IND-3PL.SBJ

(for the purpose of) We will prepare a meal for the feast. |

| Signifies the beneficiary of the statement | Piquum Piquk-ERG uligruat blanket-ABS-PL paipiuranun baby-PL-ALL qiḷaŋniqsuq. knit-IND-3SG

(for) Evidently Piquk knits blankets for babies. |

| Marks the noun that is being addressed to | Qaliŋaŋmun Qaliŋaŋmun-ALL uqautirut tell-IND-3PL.SBJ

(to) They (plural) told Qaliŋak. |

| Endings | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| singular | -mun | aġnauraq girl → → aġnauramun (to the) girl |

| dual | [dual absolutive stem] -nun | aġnaurak (two) girls → → aġnauraŋ* (with two) girls |

| plural | [singular absolutive stem] -nun | aġnauraq girl → → aġnauranun (to the two) girls |

*It is unclear as to whether this example is regular for the dual form or not.

Numerals

[edit]Iñupiaq numerals are base-20 with a sub-base of 5. The numbers 1 to 20 are:[24]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| atausiq | malġuk | piŋasut | sisamat | tallimat |

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| itchaksrat | tallimat malġuk | tallimat piŋasut | quliŋŋuġutaiḷaq | qulit |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| qulit atausiq | qulit malġuk | qulit piŋasut | akimiaġutaiḷaq | akimiaq |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| akimiaq atausiq | akimiaq malġuk | akimiaq piŋasut | iñuiññaġutaiḷaq | iñuiññaq |

The sub-base of five shows in the words for 5, tallimat, and 15, akimiaq, to which the numbers 1 to 3 are added to create the words for 7, 8, 16, 17 and 18, etc. (itchaksrat '6' being irregular). Apart from sisamat '4', numbers before a multiple of five are indicated with the subtractive element -utaiḷaq: quliŋŋuġutaiḷaq '9' from qulit '10', akimiaġutaiḷaq '14' from akimiaq '15', iñuiññaġutaiḷaq '19' from iñuiññaq '20'.[25]

Scores are created with the element -kipiaq, and numbers between the scores are composed by adding 1 through 19 to these. Multiples of 400 are created with -agliaq and 8000's with -pak. Note that these words will vary between singular -q and plural -t, depending on the speaker and whether they are being used for counting or for modifying a noun.

| # | Number | Semantics |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | iñuiññaq | 20 |

| 25 | iñuiññaq tallimat | 20 + 5 |

| 29 | iñuiññaq quliŋŋuġutaiḷaq | 20 + 10 − 1 |

| 30 | iñuiññaq qulit | 20 + 10 |

| 35 | iñuiññaq akimiaq | 20 + 15 |

| 39 | malġukipiaġutaiḷaq | 2×20 − 1 |

| 40 | malġukipiaq | 2×20 |

| 45 | malġukipiaq tallimat | 2×20 + 5 |

| 50 | malġukipiaq qulit | 2×20 + 10 |

| 55 | malġukipiaq akimiaq | 2×20 + 15 |

| 60 | piŋasukipiaq | 3×20 |

| 70 | piŋasukipiaq qulit | 3×20 + 10 |

| 80 | sisamakipiaq | 4×20 |

| 90 | sisamakipiaq qulit | 4×20 + 10 |

| 99 | tallimakipiaġutaiḷaq | 5×20 − 1 |

| 100 | tallimakipiaq | 5×20 |

| 110 | tallimakipiaq qulit | 5×20 + 10 |

| 120 | tallimakipiaq iñuiññaq | 5×20 + 20 |

| 140 | tallimakipiaq malġukipiaq | 5×20 + 2×20 |

| 160 | tallimakipiaq piŋasukipiaq | 5×20 + 3×20 |

| 180 | tallimakipiaq sisamakipiaq | 5×20 + 4×20 |

| 200 | qulikipiaq | 10×20 |

| 300 | akimiakipiaq | 15×20 |

| 400 | iñuiññakipiaq (in reindeer herding and math, iḷagiññaq) | 20×20 |

| 800 | malġuagliaq | 2×400 |

| 1200 | piŋasuagliaq | 3×400 |

| 1600 | sisamaagliaq | 4×400 |

| 2000 | tallimaagliaq | 5×400 |

| 2400 | tallimaagliaq iḷagiññaq | 5×400 + 400 |

| 2800 | tallimaagliaq malġuagliaq | 5×400 + 2×400 |

| 4000 | quliagliaq | 10×400 |

| 6000 | akimiagliaq | 15×400 |

| 7999 | atausiqpautaiḷaq | 8000 − 1 |

| 8000 | atausiqpak | 8000 |

| 16,000 | malġuqpak | 2×8000 |

| 24,000 | piŋasuqpak | 3×8000 |

| 32,000 | sisamaqpak | 4×8000 |

| 40,000 | tallimaqpak | 5×8000 |

| 48,000 | tallimaqpak atausiqpak | 5×8000 + 8000 |

| 72,000 | tallimaqpak sisamaqpak | 5×8000 + 4×8000 |

| 80,000 | quliqpak | 10×8000 |

| 120,000 | akimiaqpak | 15×8000 |

| 160,000 | iñuiññaqpak | 20×8000 |

| 320,000 | malġukipiaqpak | 2×20×8000 |

| 480,000 | piŋasukipiaqpak | 3×20×8000 |

| 640,000 | sisamakipiaqpak | 4×20×8000 |

| 800,000 | tallimakipiaqpak | 5×20×8000 |

| 1,600,000 | qulikipiaqpak | 10×20×8000 |

| 2,400,000 | akimiakipiaqpak | 15×20×8000 |

| 3,200,000 | iḷagiññaqpak | 400×8000 |

| 6,400,000 | malġuagliaqpak | 2×400×8000 |

| 9,600,000 | piŋasuagliaqpak | 3×400×8000 |

| 12,800,000 | sisamaagliaqpak | 4×400×8000 |

| 16 million | tallimaagliaqpak | 5x400×8000 |

| 32 million | quliagliaqpak | 10×400×8000 |

| 48 million | akimiagliaqpak | 15×400×8000 |

The system continues through compounding suffixes to a maximum of iñuiññagliaqpakpiŋatchaq (20×400×80003, ≈ 4 quadrillion), e.g.

| # | Number | Semantics |

|---|---|---|

| 64 million | atausiqpakaippaq | 1×80002 |

| 1,280 million | iñuiññaqpakaippaq | 20×80002 |

| 25.6 billion | iḷagiññaqpakaippaq | 400×80002 |

| 511,999,999,999 | atausiqpakpiŋatchaġutaiḷaq | 1×80003 − 1 |

| 512 billion | atausiqpakpiŋatchaq | 1×80003 |

| 10.24 trillion | iñuiññaqpakpiŋatchaq | 20×80003 |

| 204.8 trillion | iḷagiññaqpakpiŋatchaq | 400×80003 |

| 2.048 quadrillion | quliagliaqpakpiŋatchaq | 10×400×80003 |

There is also a decimal system for the hundreds and thousands, with the numerals qavluun for 100 and kavluutit for 1000, thus malġuk qavluun 200, malġuk kavluutit 2000, etc.[26]

Etymology

[edit]The numeral five, tallimat, is derived from the word for hand/arm. The word for 10, qulit, is derived from the word for "top", meaning the ten digits on the top part of the body. The numeral for 15, akimiaq, means something like "it goes across", and the numeral for 20, iñuiññaq means something like "entire person" or "complete person", indicating the 20 digits of all extremities.[25]

Verbal morphology

[edit]Again, Malimiutun Iñupiaq is used as a representative example in this section. The basic structure of the verb is [(verb) + (derivational suffix) + (inflectional suffix) + (enclitic)], although Lanz (2010) argues that this approach is insufficient since it "forces one to analyze ... optional ... suffixes".[19] Every verb has an obligatory inflection for person, number, and mood (all marked by a single suffix), and can have other inflectional suffixes such as tense, aspect, modality, and various suffixes carrying adverbial functions.[19]

Tense

[edit]Tense marking is always optional. The only explicitly marked tense is the future tense. Past and present tense cannot be marked and are always implied. All verbs can be marked through adverbs to show relative time (using words such as "yesterday" or "tomorrow"). If neither of these markings is present, the verb can imply a past, present, or future tense.[19]

| Tense | Example |

|---|---|

| Present | Uqaqsiitigun telephone uqaqtuguk. we-DU-talk We (two) talk on the phone. |

| Future | Uqaqsiitigun telephone uqaġisiruguk. we-DU-FUT-talk We (two) will talk on the phone. |

| Future (implied) | Iġñivaluktuq give birth probably aakauraġa my sister uvlaakun. tomorrow My sister (will) give(s) birth tomorrow. (the future tense "will" is implied by the word tomorrow) |

Aspect

[edit]Marking aspect is optional in Iñupiaq verbs. Both North Slope and Malimiut Iñupiaq have a perfective versus imperfective distinction in aspect, along with other distinctions such as: frequentative (-ataq; "to repeatedly verb"), habitual (-suu; "to always, habitually verb"), inchoative (-łhiñaaq; "about to verb"), and intentional (-saġuma; "intend to verb"). The aspect suffix can be found after the verb root and before or within the obligatory person-number-mood suffix.[19]

Mood

[edit]Iñupiaq has the following moods: Indicative, Interrogative, Imperative (positive, negative), Coordinative, and Conditional.[19][23] Participles are sometimes classified as a mood.[19]

| Mood | Usage | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicative | Declarative statements | aŋuniaqtit hunt-NZ-PL siñiktut. sleep-3-IND The hunters are sleeping. |

|

| Participles | Creating relative clauses | Putu Putu aŋutauruq young-man umiaqaqtuaq. boat-have-3-PTCP Putu is a man who owns a boat. |

"who owns a boat" is one word, where the meaning of the English "who" is implied through the case. |

| Interrogative | Formation of yes/no questions and content questions | Puuvratlavich. swim-POT-2-INTERR Can you (singular) swim? |

Yes/no question |

Suvisik? what-2DU-INTERR What are you two doing? |

Content question (this is a single word) | ||

| Imperative | A command | Naalaġiñ! listen-2SG-IMP Listen! |

|

| Conditionals | Conditional and hypothetical statements | Kakkama hungry-1SG-COND-PFV niġiŋaruŋa. eat-PFV-1SG-IND When I got hungry, I ate. |

Conditional statement. The verb "eat" is in the indicative mood because it is simply a declarative statement. |

Kaakkumi hungry-1SG-COND-IPFV niġiñiaqtuŋa. eat-FUT-1SG-IND If I get hungry, I will eat. |

Hypothetical statement. The verb "eat" is in the indicative mood because it is simply a statement. | ||

| Coordinative | Formation of dependent clauses that function as modifiers of independent clauses | Agliqiłuŋa read-1SG-COORD niġiruŋa. eat-1SG-IND [While] reading, I eat. |

The coordinative case on the verb "read" signifies that the verb is happening at the same time as the main clause ("eat" - marked by indicative because it is simply a declarative statement). |

Indicative mood endings can be transitive or intransitive, as seen in the table below.

| Indicative intransitive endings | Indicative transitive endings | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OBJECT | |||||||||||||||

| Mood marker | 3s | 3d | 3p | 2s | 2d | 2p | 1s | 1d | 1p | ||||||

| +t/ru | ŋa

guk gut |

1S

1D 1P |

S

U B J E C T |

+kI/gI | ga

kpuk kput |

kka

← ← |

tka

vuk vut |

kpiñ

↓ visigiñ |

vsik

↓ ↓ |

vsI

↓ ↓ |

1S

1D 1P |

S

U B J E C T | |||

| tin

sik sI |

2S

2D 2P |

n

ksik ksi |

kkiñ

← ← |

tin

sik si |

ŋma

vsiŋŋa vsiñŋa |

vsiguk

↓ ↓ |

vsigut

↓ ↓ |

2S

2D 2P | |||||||

| q

k t |

3S

SD 3P |

+ka/ga | a

ak at |

ik

↓← ↓← |

I

↓ It |

atin

↓ ↓ |

asik

↓ ↓ |

asI

↓ ↓ |

aŋa

aŋŋa aŋŋa |

atiguk

↓ ↓ |

atigut

↓ ↓ |

3S

3D 3P | |||

Syntax

[edit]Nearly all syntactic operations in the Malimiut dialect of Iñiupiaq—and Inuit languages and dialects in general—are carried out via morphological means.[19]

The language aligns to an ergative-absolutive case system, which is mainly shown through nominal case markings and verb agreement (see above).[19]

The basic word order is subject-object-verb. However, word order is flexible and both subject and/or object can be omitted. There is a tendency for the subject of a transitive verb (marked by the ergative case) to precede the object of the clause (marked by the absolutive case). There is likewise a tendency for the subject of an intransitive verb (marked by the absolutive case) to precede the verb. The subject of an intransitive verb and the object of a clause (both marked by the absolutive case) are usually found right before the verb. However, "this is [all] merely a tendency."[19]

Iñupiaq grammar also includes morphological passive, antipassive, causative and applicative.

Noun incorporation

[edit]Noun incorporation is a common phenomenon in Malimiutun Iñupiaq. The first type of noun incorporation is lexical compounding. Within this subset of noun incorporation, the noun, which represents an instrument, location, or patient in relation to the verb, is attached to the front of the verb stem, creating a new intransitive verb. The second type is manipulation of case. It is argued whether this form of noun incorporation is present as noun incorporation in Iñupiaq, or "semantically transitive noun incorporation"—since with this kind of noun incorporation the verb remains transitive. The noun phrase subjects are incorporated not syntactically into the verb but rather as objects marked by the instrumental case. The third type of incorporation, manipulation of discourse structure, is supported by Mithun (1984) and argued against by Lanz (2010). See Lanz's paper for further discussion.[19] The final type of incorporation is classificatory noun incorporation, whereby a "general [noun] is incorporated into the [verb], while a more specific [noun] narrows the scope".[19] With this type of incorporation, the external noun can take on external modifiers and, like the other incorporations, the verb becomes intransitive. See Nominal Morphology (Instrumental Case, Usage of Instrumental table, row four) on this page for an example.

Switch-references

[edit]Switch-references occur in dependent clauses only with third person subjects. The verb must be marked as reflexive if the third person subject of the dependent clause matches the subject of the main clause (more specifically matrix clause).[19] Compare:

| Example | Notes |

|---|---|

Kaakkama hungry-3-REFL-COND niġiŋaruq. eat-3-IND When he/she got hungry, he/she ate. |

The verb in the matrix clause (to eat) refers to the same person because the verb in the dependent clause (To get hungry) is reflexive. Therefore, a single person got hungry and ate. |

Kaaŋman hungry-3-NREFL-COND niġiŋaruq. eat-3-IND When he/she got hungry, (someone else) ate. |

The verb in the matrix clause (to eat) refers to a different singular person because the verb in the dependent clause (To get hungry) is non-reflexive. |

Text sample

[edit]This is a sample of the Iñupiaq language of the Kivalina variety from Kivalina Reader, published in 1975.

Aaŋŋaayiña aniñiqsuq Qikiqtami. Aasii iñuguġuni. Tikiġaġmi Kivaliñiġmiḷu. Tuvaaqatiniguni Aivayuamik. Qulit atautchimik qitunġivḷutik. Itchaksrat iñuuvlutiŋ. Iḷaŋat Qitunġaisa taamna Qiñuġana.

This is the English translation, from the same source:

Aaŋŋaayiña was born in Shishmaref. He grew up in Point Hope and Kivalina. He marries Aivayuaq. They had eleven children. Six of them are alive. One of the children is Qiñuġana.

Vocabulary comparison

[edit]The comparison of various vocabulary in four different dialects:

| North Slope Iñupiaq[27] | Northwest Alaska Iñupiaq[27] (Kobuk Malimiut) |

King Island Iñupiaq[28] | Qawiaraq dialect[29] | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| atausiq | atausriq | atausiq | atauchiq | 1 |

| malġuk | malġuk | maġluuk | malġuk | 2 |

| piŋasut | piñasrut | piŋasut | piŋachut | 3 |

| sisamat | sisamat | sitamat | chitamat | 4 |

| tallimat | tallimat | tallimat | tallimat | 5 |

| itchaksrat | itchaksrat | aġvinikłit | alvinilġit | 6 |

| tallimat malġuk | tallimat malġuk | tallimat maġluuk | mulġunilġit | 7 |

| tallimat piŋasut | tallimat piñasrut | tallimat piŋasut | piŋachuŋilgit | 8 |

| quliŋuġutaiḷaq | quliŋŋuutaiḷaq | qulinŋutailat | quluŋŋuġutailat | 9 |

| qulit | qulit | qulit | qulit | 10 |

| qulit atausiq | qulit atausriq | qulit atausiq | qulit atauchiq | 11 |

| akimiaġutaiḷaq | akimiaŋŋutaiḷaq | agimiaġutailaq | . | 14 |

| akimiaq | akimiaq | agimiaq | akimiaq | 15 |

| iñuiññaŋŋutaiḷaq | iñuiñaġutaiḷaq | inuinaġutailat | . | 19 |

| iñuiññaq | iñuiñaq | inuinnaq | . | 20 |

| iñuiññaq qulit | iñuiñaq qulit | inuinaq qulit | . | 30 |

| malġukipiaq | malġukipiaq | maġluutiviaq | . | 40 |

| tallimakipiaq | tallimakipiaq | tallimativiaq | . | 100 |

| kavluutit, malġuagliaq qulikipiaq | kavluutit | kabluutit | . | 1000 |

| nanuq | nanuq | taġukaq | nanuq | polar bear |

| ilisaurri | ilisautri | iskuuqti | ilichausrirri | teacher |

| miŋuaqtuġvik | aglagvik | iskuuġvik | naaqiwik | school |

| aġnaq | aġnaq | aġnaq | aŋnaq | woman |

| aŋun | aŋun | aŋun | aŋun | man |

| aġnaiyaaq | aġnauraq | niaqsaaġruk | niaqchiġruk | girl |

| aŋutaiyaaq | aŋugauraq | ilagaaġruk | ilagaaġruk | boy |

| Tanik | Naluaġmiu | Naluaġmiu | Naluaŋmiu | white person |

| ui | ui | ui | ui | husband |

| nuliaq | nuliaq | nuliaq | nuliaq | wife |

| panik | panik | panik | panik | daughter |

| iġñiq | iġñiq | qituġnaq | . | son |

| iglu | tupiq | ini | ini | house |

| tupiq | palapkaaq | palatkaaq, tuviq | tupiq | tent |

| qimmiq | qipmiq | qimugin | qimmuqti | dog |

| qavvik | qapvik | qappik | qaffik | wolverine |

| tuttu | tuttu | tuttu | tuttupiaq | caribou |

| tuttuvak | tiniikaq | tuttuvak, muusaq | . | moose |

| tulugaq | tulugaq | tiŋmiaġruaq | anaqtuyuuq | raven |

| ukpik | ukpik | ukpik | ukpik | snowy owl |

| tatqiq | tatqiq | taqqiq | taqqiq | moon/month |

| uvluġiaq | uvluġiaq | ubluġiaq | ubluġiaq | star |

| siqiñiq | siqiñiq | mazaq | machaq | sun |

| niġġivik | tiivlu, niġġivik | tiivuq, niġġuik | niġġiwik | table |

| uqautitaun | uqaqsiun | qaniqsuun | qaniqchuun | telephone |

| mitchaaġvik | mirvik | mizrvik | mirvik | airport |

| tiŋŋun | tiŋmisuun | silakuaqsuun | chilakuaqchuun | airplane |

| qai- | mauŋaq- | qai- | qai- | to come |

| pisuaq- | pisruk- | aġui- | aġui- | to walk |

| savak- | savak- | sawit- | chuli- | to work |

| nakuu- | nakuu- | naguu- | nakuu- | to be good |

| maŋaqtaaq | taaqtaaq | taaqtaaq | maŋaqtaaq, taaqtaaq | black |

| uvaŋa | uvaŋa | uaŋa | uaŋa, waaŋa | I, me |

| ilviñ | ilvich | iblin | ilvit | you (singular) |

| kiña | kiña | kina | kina | who |

| sumi | nani, sumi | nani | chumi | where |

| qanuq | qanuq | qanuġuuq | . | how |

| qakugu | qakugu | qagun | . | when (future) |

| ii | ii | ii'ii | ii, i'i | yes |

| naumi | naagga | naumi | naumi | no |

| paniqtaq | paniqtaq | paniqtuq | pipchiraq | dried fish or meat |

| saiyu | saigu | saayuq | chaiyu | tea |

| kuuppiaq | kuukpiaq | kuupiaq | kuupiaq | coffee |

See also

[edit]- Inuit languages

- Inuit-Yupik-Unangan languages

- Edna Ahgeak MacLean, a well-known Iñupiaq linguist

- Iñupiat people

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ www.kipigniutit.org/. Kipiġniuqtit Iñupiuraallanikun https://www.kipigniutit.org/_files/ugd/622f90_b56e79dff4164f3ca875ea2fbb1a9ef5.pdf. Retrieved 2023-09-11.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Chappell, Bill (21 April 2014). "Alaska OKs Bill Making Native Languages Official". NPR.

- ^ "Populations and Speakers | Alaska Native Language Center". Archived from the original on 2017-04-28. Retrieved 2016-08-11.

- ^ "Iñupiatun, North Alaskan". Ethnologue.

- ^ a b "Alaska's indigenous languages now official along with English". Reuters. 2016-10-24. Retrieved 2017-02-19.

- ^ "Sheldon Jackson in Historical Perspective". www.alaskool.org. Retrieved 2016-08-11.

- ^ Krauss, Michael E. 1974. Alaska Native language legislation. International Journal of American Linguistics 40(2).150-52.

- ^ Naiden, Alena. "Alaska Native linguists create a digital Inupiaq dictionary, combining technology, accessibility and language preservation". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved 2025-10-09.

- ^ D'oro, Rachel (2 September 2018). "Facebook adds Alaska's Inupiaq as language option". PBS NewsHour. NewsHour Productions LLC. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ "Alaskan doctoral student creates Iñupiaq Wordle version". 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Wordle takes off — this time, in Iñupiaq". Anchorage Daily News.

- ^ a b c d e f "Iñupiaq/Inupiaq". languagegeek.com. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Dorais, Louis-Jacques (2010). The Language of the Inuit: Syntax, Semantics, and Society in the Arctic. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7735-3646-3.

- ^ a b c Burch 1980 Ernest S. Burch, Jr., Traditional Eskimo Societies in Northwest Alaska. Senri Ethnological Studies 4:253-304

- ^ Spencer 1959 Robert F. Spencer, The North Alaskan Eskimo: A study in ecology and society, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, 171 : 1-490

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak MacLean, Edna Ahgeak (1986). North Slope Iñupiaq Grammar: First Year. Alaska Native Language Center, College of Liberal Arts; University of Alaska, Fairbanks. ISBN 1-55500-026-6.

- ^ a b c Lowe, Ronald (1984). Uummarmiut Uqalungiha Mumikhitchiȓutingit: Basic Uummarmiut Eskimo Dictionary. Inuvik, Northwest Territories, Canada: Committee for Original Peoples Entitlement. pp. xix–xxii. ISBN 0-9691597-1-4.

- ^ a b c Kaplan, Lawrence (1981). Phonological Issues In North Alaska Iñupiaq. Alaska Native Language Center, University of Fairbanks. p. 85. ISBN 0-933769-36-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Lanz, Linda A. (2010). A grammar of Iñupiaq morphosyntax (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). Rice University. hdl:1911/62097.

- ^ Kaplan, Larry (1981). North Slope Iñupiaq Literacy Manual. Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks.

- ^ Project Naming Archived 2006-10-28 at the Wayback Machine, the identification of Inuit portrayed in photographic collections at Library and Archives Canada

- ^ Kaplan, Lawrence (2000). "L'Iñupiaq et les contacts linguistiques en Alaska". In Tersis, Nicole and Michèle Therrien (eds.), Les langues eskaléoutes: Sibérie, Alaska, Canada, Groënland, pages 91-108. Paris: CNRS Éditions. For an overview of Iñupiaq phonology, see pages 92-94.

- ^ a b c Seiler, Wolf A. (2012). Iñupiatun Eskimo Dictionary (PDF). Sil Language and Culture Documentation and Descriptions. SIL International. pp. Appendix 7. ISSN 1939-0785. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-28.

- ^ MacLean (2014) Iñupiatun Uqaluit Taniktun Sivuninit / Iñupiaq to English Dictionary, p. 840 ff

- ^ a b Clark, Bartley William (2014). Iñupiatun Uqaluit Taniktun Sivuninit/Iñupiaq to English Dictionary (11 ed.). Fairbanks: University of Alaska. pp. 831–841. ISBN 9781602232334.

- ^ Ulrich, Alexis. "Inupiaq numbers". Of Languages and Numbers.

- ^ a b "Interactive IñupiaQ Dictionary". Alaskool.org. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ^ "Ugiuvaŋmiuraaqtuaksrat / Future King Island Speakers". Ankn.uaf.edu. 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ^ Agloinga, Roy (2013). Iġałuiŋmiutullu Qawairaġmiutullu Aglait Nalaunaitkataat. Atuun Publishing Company.

Print resources

[edit]- Barnum, Francis. Grammatical Fundamentals of the Innuit Language As Spoken by the Eskimo of the Western Coast of Alaska. Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1970.

- Blatchford, DJ. Just Like That!: Legends and Such, English to Iñupiaq Alphabet. Kasilof, AK: Just Like That!, 2003. ISBN 0-9723303-1-3

- Bodfish, Emma, and David Baumgartner. Iñupiat Grammar. Utqiaġvigmi: Utqiaġvium minuaqtuġviata Iñupiatun savagvianni, 1979.

- Kaplan, Lawrence D. Phonological Issues in North Alaskan Iñupiaq. Alaska Native Language Center research papers, no. 6. Fairbanks, Alaska (Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, Fairbanks 99701): Alaska Native Language Center, 1981.

- Kaplan, Lawrence. Iñupiaq Phrases and Conversations. Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, 2000. ISBN 1-55500-073-8

- MacLean, Edna Ahgeak. Iñupiallu Tanņiḷḷu Uqaluņisa Iḷaņich = Abridged Iñupiaq and English Dictionary. Fairbanks, Alaska: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, 1980.

- Lanz, Linda A. A Grammar of Iñupiaq Morphosyntax. Houston, Texas: Rice University, 2010.

- MacLean, Edna Ahgeak. Beginning North Slope Iñupiaq Grammar. Fairbanks, Alaska: Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska, 1979.

- Seiler, Wolf A. Iñupiatun Eskimo Dictionary. Kotzebue, Alaska: NANA Regional Corporation, 2005.

- Seiler, Wolf. The Modalis Case in Iñupiat: (Eskimo of North West Alaska). Giessener Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, Bd. 14. Grossen-Linden: Hoffmann, 1978. ISBN 3-88098-019-5

- Webster, Donald Humphry, and Wilfried Zibell. Iñupiat Eskimo Dictionary. 1970.

External links and language resources

[edit]There are a number of online resources that can provide a sense of the language and information for second language learners.

- Atchagat Pronunciation Video by Aqukkasuk

- Alaskool Iñupiaq Language Resources

- Animal Names in Brevig Mission Dialect

- Atchagat App by Grant and Reid Magdanz—Allows you to text using Iñupiaq characters. (For all Alaska Native languages, including Iñupiaq, see updated Chert app by the same developers.)

- Dictionary of Iñupiaq, 1970 University of Fairbanks PDF by Webster

- Endangered Alaskan Language Goes Digital from National Public Radio

- Iñupiaq Handbook for Teachers (A story of the Iñupiaq language and further resources)

- University of Alaska Fairbanks Iñupiat Language Community Site

- North Slope Grammar Second Year by Dr. Edna MacLean PDF

- Online Iñupiaq morphological analyser

- Storybook—The Teller Reader, A Collection of Stories in the Brevig Mission Dialect

- Storybook—Quliaqtuat Mumiaksrat by Alaska Native Language Program, UAF and Dr. Edna MacLean

- The dialects of Iñupiaq- From Languagegeek.com, includes Northern Alaskan Consonants (US alphabet), Northern Alaskan Vowels, Seward Peninsula Consonants, Seward Peninsula Vowels

- InupiaqWords YouTube account

- https://scholarship.rice.edu/bitstream/handle/1911/62097/3421210.PDF?sequence=1 — Linda A. Lanz's Grammar of Iñupiaq (Malimiutun) Morphosyntax. The majority of grammar introduced on this Wikipedia page is cited from this grammar. Lanz's explanations are very detailed and thorough—a great source for gaining a more in-depth understanding of Iñupiaq grammar.

| Item | Label/en | native label | Code | distribution map | number of speakers, writers, or signers | UNESCO language status | Ethnologue language status | ?itemwiki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q36806 | Southern Quechua | qu:Urin Qichwa qu:Qhichwa qu:Qichwa |

qu |  |

6000000 | 2 vulnerable | Quechua Wikipedia | |

| Q35876 | Guarani | gn:Avañe'ẽ | gn |  |

4850000 | 1 safe | 1 National | Guarani Wikipedia |

| Q4627 | Aymara | ay:Aymar aru | ay |  |

4000000 | 2 vulnerable | Aymara Wikipedia | |

| Q13300 | Nahuatl | nah:Nawatlahtolli nah:nawatl nah:mexkatl |

nah |  |

1925620 | 2 vulnerable | Nahuatl Wikipedia | |

| Q891085 | Wayuu | guc:Wayuunaiki | guc |  |

300000 | 2 vulnerable | 5 Developing | Wayuu Wikipedia |

| Q33730 | Mapudungun | arn:Mapudungun | arn |  |

300000 | 3 definitely endangered | 6b Threatened | Mapuche Wikipedia |

| Q13310 | Navajo | nv:Diné bizaad nv:Diné |

nv |  |

169369 | 2 vulnerable | 6b Threatened | Navajo Wikipedia |

| Q25355 | Greenlandic | kl:Kalaallisut | kl |  |

56200 | 2 vulnerable | 1 National | Greenlandic Wikipedia |

| Q29921 | Inuktitut | ike-cans:ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᑦ iu:Inuktitut |

iu |  |

39770 | 2 vulnerable | Inuktitut Wikipedia | |

| Q33388 | Cherokee | chr:ᏣᎳᎩ ᎧᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ chr:ᏣᎳᎩ |

chr |  |

12300 | 4 severely endangered | 8a Moribund | Cherokee Wikipedia |

| Q33390 | Cree | cr:ᐃᔨᔨᐤ ᐊᔨᒧᐎᓐ' cr:nēhiyawēwin |

cr |  |

10875 8040 |

Cree Wikipedia | ||

| Q32979 | Choctaw | cho:Chahta anumpa cho:Chahta |

cho |  |

9200 | 2 vulnerable | 6b Threatened | Choctaw Wikipedia |

| Q56590 | Atikamekw | atj:Atikamekw Nehiromowin atj:Atikamekw |

atj |  |

6160 | 2 vulnerable | 5 Developing | Atikamekw Wikipedia |

| Q27183 | Iñupiaq | ik:Iñupiatun | ik |  |

5580 | 4 severely endangered | Inupiat Wikipedia | |

| Q523014 | Muscogee | mus:Mvskoke | mus |  |

4300 | 3 definitely endangered | 7 Shifting | Muscogee Wikipedia |

| Q33265 | Cheyenne | chy:Tsêhesenêstsestôtse | chy |  |

2400 | 3 definitely endangered | 8a Moribund | Cheyenne Wikipedia |

Iñupiaq language

View on GrokipediaClassification and Geographic Distribution

Linguistic Affiliation

The Iñupiaq language belongs to the Eskimo-Aleut language family, which encompasses languages spoken across the Arctic regions of North America, Siberia, and the Aleutian Islands.[3] This family divides into two primary branches: the Eskimo languages and the Aleut languages, with Iñupiaq situated within the Eskimo branch.[4] The Eskimo branch further splits into the Yupik languages of southwestern Alaska and Siberia and the Inuit languages of northern Alaska, Canada, and Greenland.[5] Iñupiaq specifically affiliates with the Inuit subgroup, descending from Proto-Inuit, and exhibits close genetic ties to other Inuit varieties such as Inuktitut in Canada and Kalaallisut in Greenland.[1][6] These relationships stem from shared phonological, morphological, and syntactic features typical of Inuit languages, including polysynthetic word formation and ergative-absolutive alignment.[2] While mutually intelligible to varying degrees with neighboring Inuit dialects, Iñupiaq maintains distinct lexical and phonological traits adapted to its Alaskan context.[1]Speaker Population and Regions

The Iñupiaq language is primarily spoken in northern Alaska, with communities concentrated in the North Slope Borough and Northwest Arctic Borough. Smaller numbers of speakers reside in villages along the Bering Strait and Kobuk River regions. While historically extending toward the Mackenzie Delta in Canada's Northwest Territories, contemporary fluent usage is negligible there, with the language's core distribution remaining within Alaska.[1][2] As of a 2023 survey conducted in northwest Alaska communities, the number of fluent Iñupiaq speakers stands at approximately 1,250, marking a decline from 2,144 recorded in a prior assessment around 2010. This figure represents proficient adult speakers, predominantly over the age of 40, amid broader intergenerational transmission challenges. Ethnic Iñupiat population in Alaska, estimated at 13,500 to 15,700 individuals per linguistic surveys, provides a potential speaker base, though self-reported language use in the 2020 U.S. Census indicates limited proficiency among younger cohorts.[7][2][8] Regional speaker densities vary by dialect area, with higher concentrations in remote Arctic villages like Utqiaġvik (Barrow), Point Hope, and Noatak, where cultural immersion supports retention. Urban migration to Anchorage and Fairbanks has diluted usage among diaspora populations, contributing to vitality concerns documented in Alaska Native language assessments.[1][7]Historical Development

Prehistoric Origins and Proto-Inuit Roots

The Iñupiaq language descends from Proto-Inuit, the reconstructed common ancestor of the Inuit languages spoken across northern Alaska, Canada, and Greenland.[4] Linguistic evidence places the timeframe for Proto-Inuit around 1,000 years ago, coinciding with the predecessors of the Thule culture in the Bering Strait region of Alaska.[4] [9] This proto-language emerged from earlier Proto-Eskimoan forms, following the divergence of the Eskimoan branch from Aleut within the Eskimo-Aleut family, estimated at 4,000 to 2,000 BCE based on comparative phonological and lexical studies.[10] [11] Prehistoric roots of Iñupiaq trace to Eskimoan-speaking populations who entered northern Alaska around 2,500 to 3,000 years ago, linked to archaeological cultures such as Old Bering Sea (circa 500 BCE to 200 CE) and Punuk (circa 200 to 900 CE). These groups adapted linguistic structures to Arctic subsistence patterns, including whaling and caribou hunting, which influenced vocabulary for environmental and technological terms retained in Iñupiaq.[10] The subsequent Birnirk culture (circa 500 to 900 CE) in northwest Alaska represents a direct precursor, with Proto-Inuit speakers transitioning to more specialized bow-and-arrow technologies and umiak boating, facilitating coastal mobility. By approximately 1,000 years ago, Proto-Inuit had stabilized, showing minimal change until regional dialectal diversification in the early second millennium CE.[9] Comparative reconstructions of Proto-Inuit phonology reveal a consonant inventory with uvulars and pharyngeals, alongside vowel harmony systems partially preserved in Iñupiaq dialects, distinguishing it from Yupik branches that diverged earlier from shared Proto-Eskimoan around 2,000 to 1,000 years ago.[9] Lexical evidence, such as cognates for kinship and sea-mammal hunting (e.g., reconstructed *qilaq "beluga" across Inuit varieties), supports continuity from Proto-Inuit, underscoring causal links between linguistic evolution and prehistoric migrations from Siberia via the Bering Strait.[10] These origins reflect isolation in Arctic refugia, limiting external substrate influences compared to southern Alaskan languages, with genetic-linguistic correlations affirming Eskimoan peopling of the region independent of earlier Paleo-Eskimo groups like Dorset, whose languages left no trace in modern Inuit forms.[12]European Contact and Initial Documentation (19th Century)

European contact with Iñupiaq-speaking communities along Alaska's Arctic coast intensified in the mid-19th century, primarily through American whaling ships and trading vessels that ventured into the region following the discovery of bowhead whale populations. These interactions, beginning around the 1840s, introduced rudimentary exchanges in trade goods and basic vocabulary, though systematic linguistic recording remained limited until scientific expeditions arrived.[13] Initial documentation efforts were spearheaded by U.S. government personnel during the International Polar Year of 1882–1883, when a meteorological station was established at Point Barrow, home to North Slope Iñupiaq speakers. John Murdoch, a sergeant with the U.S. Signal Corps serving as the station's observer and de facto ethnographer from 1881 to 1883, compiled the earliest substantial linguistic records of the Point Barrow dialect, including a vocabulary list of approximately 1,000 terms covering daily life, environment, and kinship.[14] His fieldwork involved direct elicitation from local informants, resulting in notes on numerals, measurements, and basic grammatical structures, which highlighted the language's polysynthetic nature.[15] Murdoch's materials were formalized in the 1892 publication Ethnological Results of the Point Barrow Expedition, part of the Ninth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, providing the first printed comparative data on Iñupiaq phonology and lexicon for non-local scholars.[16] Concurrently, in the Bering Strait region encompassing Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq dialects, Edward William Nelson, a Signal Corps weather observer stationed from 1877 to 1881, gathered ethnographic and linguistic data on local Eskimo varieties, including vocabularies and narratives that bridged Iñupiaq and adjacent Yup'ik forms.[17] Nelson's collections, later detailed in his 1899 report The Eskimo about Bering Strait, emphasized practical terminology related to subsistence and material culture, though his primary focus was broader ethnology rather than dedicated grammar.[18] These 19th-century records, derived from extended immersion by military personnel rather than professional linguists, established foundational datasets but were constrained by orthographic inconsistencies and the observers' limited training in indigenous language analysis. No formal grammars emerged until later, and early efforts prioritized utilitarian vocabularies over comprehensive description, reflecting the exploratory priorities of polar science over philology.[16]Modern Era: Suppression, Standardization, and Policy Impacts (20th-21st Centuries)

During the 20th century, U.S. assimilation policies significantly suppressed the Iñupiaq language through mandatory boarding schools operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, where children were forcibly removed from families and punished—often physically—for speaking indigenous languages.[19] Survivors reported suppressing Iñupiaq after witnessing beatings and humiliation for inadvertent use, leading to widespread language loss across generations.[20] This era's educational mandates prioritized English, contributing to a sharp decline in fluent speakers; by the late 20th century, intergenerational transmission had eroded, with younger cohorts rarely acquiring proficiency. Standardization efforts began in 1946 with the development of a Roman-based orthography for the North Slope dialect by Iñupiaq minister Roy Ahmaogak and linguist Eugene Nida, introducing letters to represent distinct sounds like geminated consonants.[21] By the 1970s, this system expanded as the accepted standard across northern Alaskan varieties, facilitated by the Alaska Native Language Center established in 1972 for documentation and unification.[16] These initiatives aimed to enable literacy and media production, though dialectal variations persisted, limiting full unification.[22] In the 21st century, policy shifts supported revitalization, including Alaska's 2014 recognition of Iñupiaq among 20 Native languages as co-official with English via House Bill 216, alongside the creation of the Alaska Native Language Preservation and Advisory Council in 2012.[23] Programs at institutions like Iḷisaġvik College have produced grammar resources, apps, and immersion curricula with federal funding, while the 2024 Ayaruq Action Plan targets speaker growth through education.[24][25] Despite increased interest and university-level teaching, fluent Iñupiaq speakers dropped from 2,144 in 2010 to 1,250 by 2023, reflecting ongoing challenges from historical suppression.[26]Dialectal Variation

Primary Dialect Groups

The Iñupiaq language, spoken across northern and northwestern Alaska, is classified into two primary dialect groups: North Alaskan Iñupiaq and Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq. These groups reflect geographic and historical divisions among Iñupiaq communities, with North Alaskan encompassing coastal and interior varieties along the Arctic slope and river valleys, while Seward Peninsula varieties are concentrated on the peninsula's coastal and island communities.[1][2] North Alaskan Iñupiaq includes the North Slope dialect, spoken in Arctic coastal villages such as Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow), Nuiqsut, Kaktovik, Atqasuk, Wainwright, Point Lay, Point Hope, and Kivalina, extending from Barter Island eastward to Kivalina westward. This dialect features conservative phonological traits, including retention of certain Proto-Inuit sounds. The Malimiut dialect, part of the same group, is used in interior areas like the Kobuk River valley, Noatak, and Selawik, showing influences from adjacent regions but maintaining mutual intelligibility with North Slope varieties.[1][3][27] Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq comprises the Bering Strait dialect, spoken in villages including Shishmaref, Wales, Teller, and Marys Igloo, characterized by innovations such as vowel shifts and lexical borrowings from neighboring languages. The Qawiaraq (or Qawairaq) dialect, also within this group, is associated with King Island and nearby coastal areas, though it faces endangerment with few fluent speakers remaining as of the early 21st century. These peninsula dialects exhibit greater divergence from North Alaskan forms, particularly in prosody and certain morphological patterns.[2][28][1]Inter-Dialectal Differences and Mutual Intelligibility

Iñupiaq exhibits notable dialectal variation across its primary groups: North Alaskan Iñupiaq, encompassing the North Slope and Malimiut dialects, and Seward Peninsula Iñupiaq, including Qawiaraq and Bering Strait varieties.[1] These differences manifest in phonology, lexicon, and morphology, with phonological variations often involving palatalization, consonant gemination, and the presence of glottal stops or fricatives in certain regions.[29] [1] For instance, Northern varieties like North Slope employ palatalized sounds such as ch and ñ, contrasting with t and s or n in Seward Peninsula dialects; similarly, double consonants are more prevalent in North Slope (e.g., alla) compared to forms like ałła in Ugiuvaŋmiutun.[29] Lexical distinctions are evident in core vocabulary, where semantic shifts occur between dialects. In North Slope Iñupiaq, tupiq denotes a 'tent' and iglu a 'house', whereas in Malimiut, tupiq refers to a 'house'.[1] Other examples include 'dog' as qimmiq in North Slope versus qipmiq in Malimiut, and negation or gratitude terms varying widely: 'no' is naumi in North Slope and Qawiaraq but naagga in Malimiutun, while 'thank you' ranges from quyanaq in North Slope to taikuu in Malimiutun.[1] [29] Morphological differences appear in suffixes and verb stems, such as 'they are cooking' rendered as iarut in Seward Peninsula dialects versus igarut in North Alaskan ones, and 'talk' as qaniqtut in the former group compared to uqaqtut in the latter.[1] Mutual intelligibility is high between closely related dialects, such as North Slope and Malimiut, where speakers can readily comprehend each other despite lexical and phonological variances.[1] However, comprehension decreases between North Alaskan and Seward Peninsula varieties due to accumulated phonological, lexical, and morphological divergences, often requiring prior exposure or adaptation for effective communication.[1] Adjacent dialects within the broader Inuit continuum generally maintain intelligibility, but greater geographic separation correlates with reduced mutual understanding, reflecting the gradual dialect chain characteristic of Inuit languages.[30]Phonological Features

Consonant and Vowel Inventory

The Iñupiaq language exhibits a relatively simple vowel system consisting of three phonemes: /a/, /i/, and /u/. These vowels occur in short and long forms (/aː/, /iː/, /uː/), with length contrastive in most positions, and form diphthongs such as /ai/, /au/, /ia/, /iu/, /ua/, and /ui/.[22][27] Some analyses posit an underlying schwa-like vowel /ə/ (or weak /i/), which alternates with surface /a/ or /u/ in certain morphological contexts and may delete, but the surface phonemic inventory remains three vowels across dialects.[22] The vowel /i/ notably triggers palatalization of preceding coronal or velar consonants in many dialects.[22] The consonant inventory is richer, typically comprising 18 to 24 phonemes depending on dialect and analysis, with stops, fricatives, nasals, approximants, and glides represented across bilabial, alveolar, palatal, velar, uvular, and glottal places of articulation.[31][22] Long (geminate) consonants arise phonologically, often via suffixation or truncation, but are not underlying phonemes. Consonant clusters are limited, generally to two members medially, and words do not begin or end with clusters.[22] Dialectal variation affects realizations, such as stronger palatalization in Kobuk versus North Slope dialects, and alternations like stops to fricatives intervocalically (e.g., /q/ to [ɣ, ʁ, β]).[31][22] The following table presents a representative inventory for North Alaskan Iñupiaq dialects, using IPA symbols with common orthographic equivalents in parentheses where standardized (e.g., North Slope orthography).[22][27]| Manner/Place | Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | p (p) | t (t) | t͡ʃ (ch) | k (k) | q (q) | ʔ (') |

| Fricatives | β/v (v) | s (s) | ʃ (sr) | x (kh) | χ (qh/ġ) | h (h) |

| Nasals | m (m) | n (n) | ɲ (ñ) | ŋ (ŋ) | ɴ (ŋ/ƾ) | |

| Approximants/Liquids | l (l)/ɬ (ḷ) | j (y) | ɣ (g) | ʁ (r/ġ) |

Dialect-Specific Phonological Processes

North Alaskan Iñupiaq dialects, including the North Slope (Barrow) and Kobuk sub-dialects, feature consonant weakening that targets stops in alternate syllables, converting them to voiced fricatives (e.g., /k/ → [ɣ], /q/ → [ʁ]) intervocalically after the initial vowel mora, with exceptions for roots marked underlyingly or before high vowels. Barrow exhibits more regressive assimilation in clusters, as in utkusik → ukkusik 'cooking pot', while Kobuk shows reduced assimilation due to penultimate /i/ syncope blocking it, yielding forms like anutmun 'to the man' from */anuti + mun/ instead of full coalescence. Intervocalic continuants like /ɣ/ or /ɬ/ undergo deletion, especially in geminates, but are blocked by long vowels or /i/, a process more consistent in Barrow than in Kobuk where cluster restructuring prevails.[22] Palatalization distinguishes North Alaskan varieties through a "strong i" (from Proto-Inuit */i/) versus "weak i" (from */ə/) contrast, preserved after schwa merger with /i/. In North Slope and Malimiutun (NANA) sub-dialects, strong /i/ productively palatalizes preceding alveolars—/t/ → [č], /l/ → [ł], /n/ → [ɲ]—as in ikit- 'to come' → ikičɲik (possessive), but weak /i/ does not trigger it, e.g., ini- 'life' → ininik. Malimiutun uniquely extends palatalization to /ð/ → , yielding niðisuk 'want to eat' from niði-. Seward Peninsula dialects lack this robust strong/weak distinction and palatalization productivity, aligning more with three-vowel Inuit systems.[32]| Process | North Slope (Barrow) | Kobuk (NANA) | Seward Peninsula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consonant Lenition | Extensive intervocalic stops → fricatives; full cluster assimilation (e.g., qavvik → [qavviɣ]). | Similar lenition but syncope blocks assimilation (e.g., mayugnak retains stop). | Reduced lenition; retains more stops, with /b/ insertion before /l/ (e.g., baluk 'whale' vs. North valuk).[29][22] |

| Vowel Cluster Reduction | Retains distinctions (e.g., ai → [aj]); partial leveling to [e:] in some (e.g., taimma → [te:mma]). | Merges clusters like ai/ia → [e:], au/ua → long vowels; reduces to [ui] phonetic cluster. | Greater merger into monophthongs; differs from North Alaskan in avoidance of certain diphthongs.[22] |

| Epenthesis in Plurals | Vowel insertion post-deletion (e.g., savik + t → savi:ič 'knives' via velar drop). | Similar, but syncope alters outcomes (e.g., less gemination). | Less dependent on lenition; unique suffix alternations.[22] |

Orthography

Historical Writing Attempts

The earliest documented efforts to transcribe Iñupiaq occurred during Russian and early American exploration of Alaska, with records dating to the late 1700s and early 1800s, primarily consisting of vocabulary lists and short phrases captured for ethnographic or navigational purposes.[16] These initial writings employed inconsistent adaptations of the Latin or Cyrillic alphabets, reflecting the explorers' native scripts rather than systematic phonetic representation suited to Iñupiaq's phonological structure, such as its uvular consonants and vowel harmony.[28] Russian expeditions, including Lavrentiy Zagoskin's 1842–1843 survey of interior regions like the Selawik area, produced some of the first lexical notations in Iñupiaq-speaking territories, though these prioritized utility over standardization and did not foster native literacy.[33] In the mid-to-late 19th century, following the U.S. acquisition of Alaska in 1867, American whalers, traders, and Presbyterian missionaries like Sheldon Jackson expanded contact but contributed only sporadic, non-uniform transcriptions, often in personal journals or basic educational materials.[34] These attempts lacked a unified orthographic framework, as priorities centered on English instruction in mission schools rather than developing a Iñupiaq script; for instance, no comprehensive missionary-led system emerged comparable to those for neighboring Yupik languages.[35] Native speakers occasionally devised pictographic notations in the early 1900s as informal aids for personal or communal records, known as Alaskan Picture Writing, but these were ideographic rather than alphabetic and did not evolve into broader writing systems.[36] Overall, pre-20th-century writing efforts remained fragmented and externally driven, yielding no enduring orthography due to the language's oral tradition, geographic isolation, and the dominance of English in colonial administration and education; full standardization awaited linguistic fieldwork in the mid-20th century.[16]Contemporary Roman-Based System and Standardization Efforts