Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Varina Davis

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

Varina Anne Banks Davis (née Howell; May 7, 1826 – October 16, 1906) was the only First Lady of the Confederate States of America, and the longtime second wife of President Jefferson Davis.[1] She moved to the presidential mansion in Richmond, Virginia, in mid-1861, and lived there for the remainder of the Civil War. Born and raised in the Southern United States and educated in Philadelphia, she had family on both sides of the conflict and unconventional views for a woman in her public role. She did not support the Confederacy's position on slavery, and was ambivalent about the war.

Key Information

Davis became a writer after the war, completing her husband's memoir. She was recruited by Kate (Davis) Pulitzer, a purportedly distant cousin of Varina’s husband and wife of publisher Joseph Pulitzer, to write articles and eventually a regular column for the New York World. Widowed in 1889, Davis moved to New York with her youngest daughter Winnie in 1891 to work at writing. She enjoyed urban life. In her old age, she attempted to reconcile prominent figures of the North and South.

Early life and education

[edit]Varina Anne Banks Howell was born in 1826 at Natchez, Mississippi, the daughter of William Burr Howell and Margaret Louisa Kempe. Her father was from a distinguished family in New Jersey: His father, Richard Howell, served several terms as governor of New Jersey and died when William was a boy. William inherited little money and used family connections to become a clerk in the Bank of the United States.[citation needed]

William Howell relocated to Mississippi, when new cotton plantations were being rapidly developed. There he met and married Margaret Louisa Kempe (1806–1867), born in Prince William County, Virginia. Her wealthy planter family had moved to Mississippi before 1816.[2] She was the daughter of Colonel James Kempe (sometimes spelled Kemp), a Scots-Irish immigrant from Ulster who became a successful planter and major landowner in Virginia and Mississippi, and Margaret Graham, born in Prince William County. Margaret Graham was illegitimate as her parents, George Graham, a Scots immigrant, and Susanna McAllister (1783–1816) of Virginia, never officially married.[3][4]

After moving his family from Virginia to Mississippi, James Kempe also bought land in Louisiana, continuing to increase his holdings and productive capacity. When his daughter married Howell, he gave her a dowry of 60 slaves and 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) of land in Mississippi.[5] William Howell worked as a planter, merchant, politician, postmaster, cotton broker, banker, and military commissary manager, but never secured long-term financial success. He lost the majority of Margaret's sizable dowry and inheritance through bad investments and their expensive lifestyle. They suffered intermittent serious financial problems throughout their lives.[6]

Varina was born in Natchez, Mississippi, as the second Howell child of eleven, seven of whom survived to adulthood. She was later described as tall and thin, with an olive complexion attributed to Welsh ancestors.[7] Later, when she was living in Richmond as the unpopular First Lady of the Confederacy, critics described her as looking like a mulatto or Indian "squaw".[8]

When Varina was thirteen, her father declared bankruptcy. The Howell family home, furnishings and slaves were seized by creditors to be sold at public auction.[9]

Her wealthy maternal relatives intervened to redeem the family's property. It was one of several sharp changes in fortune that Varina encountered in her life. She grew to adulthood in a house called The Briars, when Natchez was a thriving city, but she learned her family was dependent on the wealthy Kempe relatives of her mother's family to avoid poverty.[citation needed]

Varina Howell was sent to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for her education, where she studied at Madame Deborah Grelaud's French School, a prestigious academy for young ladies.[10] Grelaud, a Huguenot, was a refugee from the French Revolution and had founded her school in the 1790s.[10] One of Varina's classmates was Sarah Anne Ellis, later known as Sarah Anne Dorsey, the daughter of extremely wealthy Mississippi planters. (After the Civil War, Dorsey, by then a wealthy widow, provided financial support to the Davises.)[citation needed]

While at school in Philadelphia, Varina got to know many of her northern Howell relatives; she carried on a lifelong correspondence with some, and called herself a "half-breed" for her connections in both regions.[11] After a year, she returned to Natchez, where she was privately tutored by Judge George Winchester, a Harvard graduate and family friend. She was intelligent and better educated than many of her peers, which led to tensions with Southern expectations for women.[9] In her later years, Varina referred fondly to Madame Grelaud and Judge Winchester; she sacrificed to provide the highest quality of education for her two daughters in their turn.[citation needed]

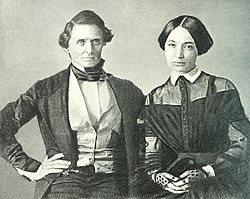

In 1843, at age 17, Howell was invited to spend the Christmas season at Hurricane Plantation, the 5,000 acres (20 km2) property of family friends Joseph Emory Davis and Eliza Van Benthuysen Davis. Her parents had named their oldest child after Joseph Davis. Located at Davis Bend, Mississippi, Hurricane was 20 miles south of Vicksburg. Davis was planning a gala housewarming with many guests and entertainers to inaugurate his lavish new mansion on the cotton plantation. (Varina described the house in detail in her memoirs.) During her stay, she met her host's much younger brother Jefferson Davis. Then thirty-five years old, Davis was a West Point graduate, former Army officer, and widower. He worked as a planter, having developed Brierfield Plantation on land his brother allowed him to use, although Joseph Davis still retained possession of the land. [citation needed]

Marriage and family

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

Jefferson Davis was a 35-year-old widower when he and Varina met. His first wife, Sarah Knox Taylor, daughter of his commanding officer Zachary Taylor while he was in the Army, had died of malaria three months after their wedding in 1835. Davis mourned her and had been reclusive in the ensuing eight years. He was beginning to be active in politics.

Shortly after first meeting him, Howell wrote to her mother:

I do not know whether this Mr. Jefferson Davis is young or old. He looks both at times; but I believe he is old, for from what I hear he is only two years younger than you are [the rumor was correct]. He impresses me as a remarkable kind of man, but of uncertain temper, and has a way of taking for granted that everybody agrees with him when he expresses an opinion, which offends me; yet he is most agreeable and has a peculiarly sweet voice and a winning manner of asserting himself. The fact is, he is the kind of person I should expect to rescue one from a mad dog at any risk, but to insist upon a stoical indifference to the fright afterward.[12]

In keeping with custom, Davis sought the permission of Howell's parents before beginning a formal courtship. They initially disapproved of him due to the many differences in background, age, and politics. Davis was a Democrat and the Howells, including Varina, were Whigs. In her memoir, Varina Howell Davis wrote that her mother was concerned about Jefferson Davis's excessive devotion to his relatives (particularly his older brother Joseph, who had largely raised him and upon whom he was financially dependent) and his near worship of his deceased first wife. The Howells ultimately consented to the courtship, and the couple became engaged shortly thereafter.[citation needed]

Their wedding was planned as a grand affair to be held at Hurricane Plantation during Christmas of 1844, but the wedding and engagement were cancelled shortly beforehand, for unknown reasons. In January 1845, while Howell was ill with a fever, Davis visited her frequently. They became engaged again. When they married on February 26, 1845, at her parents' house, a few relatives and friends of the bride attended, and none of the groom's family.

Their short honeymoon included a visit to Davis's aged mother, Jane Davis, and a visit to the grave of his first wife in Louisiana. The newlyweds took up residence at Brierfield, the plantation Davis had developed on 1,000 acres (4.0 km2) loaned to him for his use by his brother Joseph Davis. Their first residence was a two-room cottage on the property and they started construction of a main house. It became a source of contention.

Soon after their marriage, Davis's widowed and penniless sister, Amanda (Davis) Bradford, came to live on the Brierfield property along with her seven youngest children. Her brothers decided that she should share the large house which the Davises were building, but they had not consulted Varina Davis. It was an example of what she would later call interference from the Davis family in her life with her husband. Additionally, her brother-in-law Joseph Davis proved controlling, both of his brother, who was 23 years younger, and the even younger Varina – especially during her husband's absences. At the same time, her parents became more financially dependent on the Davises, to her embarrassment and resentment. Their youngest son, born after her own marriage, was named Jefferson Davis Howell in her husband's honor.

The couple had long periods of separation from early in their marriage, first as Jefferson Davis gave campaign speeches and "politicked" (or campaigned) for himself and for other Democratic candidates in the elections of 1846. He was also gone for extended periods during the Mexican War (1846–1848). Varina Davis was put under the guardianship of Joseph Davis, whom she had come to dislike intensely. Her correspondence with her husband during this time demonstrated her growing discontent, to which Jefferson was not particularly sympathetic.

Urban life in Washington, DC

[edit]

Jefferson Davis was elected in 1846 to the U.S. House of Representatives and Varina accompanied him to Washington, D.C., which she loved. She was stimulated by the social life with intelligent people and was known for making "unorthodox observations". Among them were that "slaves were human beings with their frailties" and that "everyone was a 'half breed' of one kind or another." She referred to herself as one because of her strong family connections in both North and South.[13] The Davises lived in Washington, DC, for most of the next fifteen years before the American Civil War, which gave Varina Howell Davis a broader outlook than many Southerners. It was her favorite place to live. But, as an example of their many differences, her husband preferred life on their Mississippi plantation.[14]

Soon he took leave from his Congressional position to serve as an officer in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). Varina Davis returned for a time to Briarfield, where she chafed under the supervision of her brother-in-law, Joseph. The surviving correspondence between the Davises from this period expresses their difficulties and mutual resentments. After her husband's return from the war, Varina Davis did not immediately accompany him to Washington when the Mississippi legislature appointed him to fill a Senate seat.

Ultimately, the couple reconciled. She rejoined her husband in Washington. He had unusual visibility for a freshman senator because of his connections as the son-in-law (by his late wife) and former junior officer of President Zachary Taylor. Varina Davis enjoyed the social life of the capital and quickly established herself as one of the city's most popular (and, in her early 20s, one of the youngest) hostesses and party guests. The 1904 memoir of her contemporary, Virginia Clay-Clopton, described the lively parties of the Southern families in this period with other Congressional delegations, as well as international representatives of the diplomatic corps.[15][16]

After seven childless years, in 1852, Varina Davis gave birth to a son, Samuel. Her letters from this period express her happiness and portray Jefferson as a doting father. The couple had a total of six children:

- Samuel Emory Davis, born July 30, 1852, named after his paternal grandfather; he died June 30, 1854, of an undiagnosed disease.[17]

- Margaret Howell Davis, born February 25, 1855.[18] She married Joel Addison Hayes, Jr. (1848–1919), and they lived first in Memphis, Tennessee; later they moved to Colorado Springs, Colorado. They had five children, including a daughter named after her mother; Margaret was the only Davis child to marry and raise a family. She married Joel Addison Hayes in Memphis on New Year's Day, 1876. She, her husband, and family moved to Colorado Springs in 1885, where they soon became leading members of local society. Many of J. Addison and Margaret Hayes' descendants still reside in the area. She died on July 18, 1909, at the age of 54 and is buried with the Davis family at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.[19]

- Jefferson Davis, Jr., born January 16, 1857. He died in Memphis, Tennessee, of yellow fever at age 21 on October 16, 1878, during an epidemic in the Mississippi River Valley that caused 20,000 deaths.[20]

- Joseph Evan Davis, born on April 18, 1859, died at the age of five due to an accidental fall on April 30, 1864.[21]

- William Howell Davis, born on December 6, 1861, was named for Varina's father; he died of diphtheria on October 16, 1872.[22]

- Varina Anne "Winnie" Davis was born on June 27, 1864, two months after Joseph's death. Known as the "Daughter of the Confederacy", she died at age 34 on September 18, 1898, of gastritis. After her parents had opposed her marriage in the late 1880s to a man from a Northern, abolitionist family, she never married.[23]

The Davises were devastated in 1854 when their first child died before the age of two. Varina Davis largely withdrew from social life for a time. In 1855, she gave birth to a healthy daughter, Margaret (1855–1909); followed by two sons, Jefferson, Jr., (1857–1878) and Joseph (1859–1864), during her husband's remaining tenure in Washington, D.C. The early losses of all four of their sons caused enormous grief to both the Davises.[citation needed]

During the Pierce Administration, Davis was appointed to the post of Secretary of War. He and President Franklin Pierce also formed a personal friendship that would last for the rest of Pierce's life. Their wives developed a strong respect, as well. The Pierces lost their last surviving child, Benny, shortly before his father's inauguration. They both suffered; Pierce became dependent on alcohol and Jane Appleton Pierce had health problems, including depression. At the request of the Pierces, the Davises, both individually and as a couple, often served as official hosts at White House functions in place of the President and his wife.

According to diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut, in 1860 Mrs. Davis "sadly" told a friend "The South will secede if Lincoln is made president. They will make Mr. Davis President of the Southern side. And the whole thing is bound to be a failure."[24]

Confederate First Lady

[edit]

Jefferson Davis resigned from the U.S. Senate in 1861 when Mississippi seceded. Varina Davis returned with their children to Brierfield, expecting him to be commissioned as a general in the Confederate army. He was elected as President of the Confederate States of America by the new Confederate Congress. She did not accompany him when he traveled to Montgomery, Alabama (then capital of the new country) to be inaugurated. A few weeks later, she followed and assumed official duties as the First Lady of the Confederacy.

Davis greeted the war with dread, supporting the Confederacy but not slavery. She was known to have said that:

the South did not have the material resources to win the war and white Southerners did not have the qualities necessary to win it; that her husband was unsuited for political life; that maybe women were not the inferior sex; and that perhaps it was a mistake to deny women the suffrage before the war.[13]

In the summer of 1861, Davis and her husband moved to Richmond, Virginia, the new capital of the Confederacy. They lived in a house which would come to be known as the White House of the Confederacy for the remainder of war (1861–1865). "She tried intermittently to do what was expected of her, but she never convinced people that her heart was in it, and her tenure as First Lady was for the most part a disaster," as the people picked up on her ambivalence.[25] White residents of Richmond criticized Varina Davis freely; some described her appearance as resembling "a mulatto or an Indian 'squaw'."[8]

In December 1861, she gave birth to their fifth child, William. Due to her husband's influence, her father William Howell received several low-level appointments in the Confederate bureaucracy which helped support him. The social turbulence of the war years reached the Presidential mansion; in 1864, several of the Davises' domestic slaves escaped. James Dennison and his wife, Betsey, who had served as Varina's maid, used saved back pay of 80 gold dollars to finance their escape. Henry, a butler, left one night after allegedly building a fire in the mansion's basement to divert attention.[citation needed]

In spring 1864, five-year-old Joseph Davis died in a fall from the porch at the Presidential mansion in Richmond. A few weeks later, Varina gave birth to their last child, a girl named Varina Anne Davis, who was called "Winnie". The girl became known to the public as "the Daughter of the Confederacy;" stories about and likenesses of her were distributed throughout the Confederacy during the last year of the war to raise morale. She retained the nickname for the rest of her life.[citation needed]

Postwar

[edit]When the war ended, the Davises fled South seeking to escape to Europe. They were captured by federal troops and Jefferson Davis was imprisoned at Fort Monroe in Phoebus, Virginia, for two years. Left indigent, Varina Davis was restricted to residing in the state of Georgia, where her husband had been arrested. Fearing for the safety of their older children, she sent them to friends in Canada under the care of relatives and a family servant. Initially forbidden to have any contact with her husband, Davis worked tirelessly to secure his release. She tried to raise awareness of and sympathy for what she perceived as his unjust incarceration.

After a few months Varina Davis was allowed to correspond with him. Articles and a book on his confinement helped turn public opinion in his favor. Davis and young Winnie were allowed to join Jefferson in his prison cell. The family was eventually given a more comfortable apartment in the officers' quarters of the fort.

Although released on bail and never tried for treason, Jefferson Davis had temporarily lost his home in Mississippi, most of his wealth, and his U.S. citizenship. In the late 20th century, his citizenship was posthumously restored by then President Carter. The small Davis family traveled constantly in Europe and Canada as he sought work to rebuild his fortunes.[citation needed] Davis accepted the presidency of an insurance agency headquartered in Memphis. The family began to regain some financial comfort until the Panic of 1873, when his company was one of many that went bankrupt. In 1872 their son William Davis died of typhoid fever, adding to their emotional burdens.[citation needed]

While visiting their daughters enrolled in boarding schools in Europe, Jefferson Davis received a commission as an agent for an English consortium seeking to purchase cotton from the southern United States. He returned to the US for this work. Varina Davis remained in England to visit her sister who had recently moved there, and stayed for several months. The surviving correspondence suggests her stay may have been prompted by renewed marital difficulties. Both the Davises suffered from depression due to the loss of their sons and their fortunes.[26]

She resented his attentions to other women, particularly Virginia Clay. Clay was the wife of their friend, former senator Clement Clay, a fellow political prisoner at Fort Monroe. During this period, Davis exchanged passionate letters with Virginia Clay for three years and is believed to have loved her. In 1871 Davis was reported as having been seen on a train "with a woman not his wife", and it made national newspapers.[26] Still in England, Varina was outraged.

For several years, the Davises lived apart far more than they lived together. Davis was unemployed for most of the years after the war. In 1877 he was ill and nearly bankrupt. Advised to take a home near the sea for his health, he accepted an invitation from Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey, a widowed heiress, to visit her summer cottage Beauvoir on the Mississippi Sound in Biloxi. A classmate of Varina in Philadelphia, Dorsey had become a respected novelist and historian, and had traveled extensively. She arranged for Davis to use a cottage on the grounds of her plantation. There she helped him organize and write his memoir of the Confederacy, in part by her active encouragement. She also invited Varina Davis to stay with her.[27]

Davis and her eldest daughter, Margaret Howell Hayes, disapproved of her husband's friendship with Dorsey. After Varina Davis returned to the United States, she lived in Memphis with Margaret and her family for a time.[citation needed] Gradually she began a reconciliation with her husband. She was with him at Beauvoir in 1878 when they learned that their last surviving son, Jefferson Davis, Jr., had died during a yellow fever epidemic in Memphis. That year 20,000 people died throughout the South in the epidemic. During her grieving, Varina became friends again with Dorsey.[citation needed]

Sarah Dorsey was determined to help support the former president; she offered to sell him her house for a reasonable price. Learning she had breast cancer, Dorsey made over her will to leave Jefferson Davis free title to the home, as well as much of the remainder of her financial estate. Her Percy relatives were unsuccessful in challenging the will.[27]

Her bequest provided Davis with enough financial security to provide for Varina and Winnie, and to enjoy some comfort with them in his final years.[27] When Winnie Davis completed her education, she joined her parents at Beauvoir. She had fallen in love when at college, but her parents disapproved. Her father objected to his being from "a prominent Yankee and abolitionist family" and her mother to his lack of money and being burdened by many debts. Forced to reject this man, Winnie never married.[28]

Dorsey's bequest made Winnie Davis the heiress after Jefferson Davis died in 1889. In 1891, Varina and Winnie moved to New York City. After Winnie died in 1898, she was buried next to her father in Richmond, Virginia. Varina Davis inherited Beauvoir.[29]

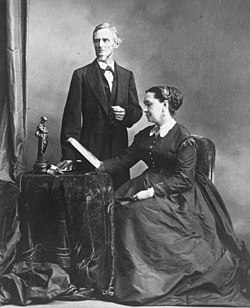

Widow

[edit]After her husband died, Varina Howell Davis completed his autobiography, publishing it in 1890 as Jefferson Davis, A Memoir.[30] At first the book sold few copies, dashing her hopes of earning some income.

Kate Davis Pulitzer, a distant cousin of Jefferson Davis and the wife of Joseph Pulitzer, a major newspaper publisher in New York, had met Varina Davis during a visit to the South. She solicited short articles from her for her husband's newspaper, the New York World. In 1891 Varina Davis accepted the Pulitzers' offer to become a full-time columnist and moved to New York City with her daughter Winnie. They enjoyed the busy life of the city. White Southerners attacked Davis for this move to the North, as she was considered a public figure of the Confederacy whom they claimed for their own.[31]

As Davis and her daughter each worked at literary careers, they lived in a series of residential hotels in New York City. (Their longest residency was at the Hotel Gerard at 123 W. 44th Street.) Varina Davis wrote many articles for the newspaper, and Winnie Davis published several novels.[citation needed]

After Winnie died in 1898, Varina Davis inherited Beauvoir. In October 1902, she sold the plantation to the Mississippi Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans for $10,000 (~$292,494 in 2024). She stipulated the facility was to be used as a Confederate veterans' home and later as a memorial to her husband. The SCV built barracks on the site, and housed thousands of veterans and their families. The plantation was used for years as a veterans' home.

Since 1953 the house has been operated as a museum to Davis. Beauvoir has been designated a National Historic Landmark. The main house has been restored and a museum built there, housing the Jefferson Davis Presidential Library.[citation needed]

Varina Howell Davis was one of numerous influential Southerners who moved to the North for work after the war; they were nicknamed "Confederate carpetbaggers".[citation needed]

In the postwar years of reconciliation, Davis became friends with Julia Dent Grant, the widow of former general and president Ulysses S. Grant, who had been among the most hated men in the South. She attended a reception where she met Booker T. Washington, head of the Tuskegee Institute, then a black college. In her old age, Davis published some of her observations and "declared in print that the right side had won the Civil War."[13]

Later years

[edit]Although saddened by the death of her daughter Winnie in 1898[32] (the fifth and last of her six children to predecease her), Davis continued to write for the World. She enjoyed a daily ride in a carriage through Central Park. [citation needed]

She was active socially until poor health in her final years forced her retirement from work and any sort of public life.[citation needed] Davis died at age 80 of double pneumonia in her room at the Hotel Majestic on October 16, 1906. She was survived by her daughter Margaret Davis Hayes and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.[33]

Legacy and honors

[edit]

Varina Howell Davis received a funeral procession through the streets of New York City. Her coffin was taken by train to Richmond, accompanied by the Reverend Nathan A. Seagle, Rector of Saint Stephen's Protestant Episcopal Church, New York City which Davis attended. She was interred with full honors by Confederate veterans at Hollywood Cemetery and was buried adjacent to the tombs of her husband and their daughter Winnie.[34]

A portrait of Mrs. Davis, titled the Widow of the Confederacy (1895), was painted by the Swiss-born American artist Adolfo Müller-Ury (1862–1947). It is held at the museum at Beauvoir. In 1918 Müller-Ury donated his profile portrait of her daughter, Winnie Davis, painted in 1897–1898, to the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Virginia.

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina caused extensive wind and water damage to Beauvoir, which houses the Jefferson Davis Presidential Library. The home was restored and reopened on June 3, 2008. Varina Howell Davis's diamond and emerald wedding ring, one of the few valuable possessions she was able to retain through years of poverty, was held by the Museum at Beauvoir and lost during the destruction of Hurricane Katrina. It was discovered on the grounds a few months later and returned to the museum.[35]

Representation in other media

[edit]- Harnett Kane's Bride of Fortune (1948), a historical novel based on Mrs. Davis[36]

- Charles Frazier's 2018 novel Varina[37]

See also

[edit]- Ellen Barnes McGinnis, Varina's housemaid who accompanied her when fleeing Richmond

References

[edit]- ^ staff, Encyclopedia Virginia. "Varina Davis (1826–1906)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved May 22, 2025.

- ^ "Marriage of William B. Howell to Margaret L. Kempe, July 17, 1823, Adams County, Mississippi", Ancestry.com. Mississippi Marriages to 1825[database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1997.

- ^ Cashin 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Note: According to the 1810 census for Prince William County, George Graham owned 24 slaves, more than many of his neighbors and a quantity that qualified him as a major planter of the period. He had one child under 16 still at home, and was living with a woman over 25. Many of his neighbors had Scottish surnames. Federal Census: Year: 1810; Census Place: Prince William, Virginia; Roll: 70; Page: 278; Image: 0181430; Family History Library Film: 00528.

- ^ Cashin 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Cashin 2006, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Wyatt-Brown 1994, p. 17.

- ^ a b "Encyclopedia of Virginia: Varina Howell Davis". Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ^ a b FRANCES CLARKE, "Review of Cashin, First Lady of the Confederacy", Harvard University Press, 2006, in Australasian Journal of American Studies, Vol. 27, No. 2 (December 2008), pp. 145–47; retrieved June 1, 2012.

- ^ a b Wyatt-Brown 1994, p. 124.

- ^ Cashin 2006, p. 11.

- ^ McIntosh, James T., ed. (1974). The Papers of Jefferson Davis. Louisiana State University Press. pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b c Cashin 2006, p. 2.

- ^ Cashin 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Virginia Clay-Clopton, A Belle in the Fifties, 1904.

- ^ Sarah E. Gardner, Blood And Irony: Southern White Women's Narratives of the Civil War, 1861–1937, University of North Carolina Press, 2006, pp. 128–30

- ^ Strode 1955, pp. 242, 268.

- ^ Strode 1955, p. 273.

- ^ "Margaret Howell Davis Hayes Chapter No. 2652". Colorado United Daughters of the Confederacy. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ^ Strode 1964, p. 436.

- ^ Cooper, William J. (2000). Jefferson Davis, American, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, p. 480.

- ^ Cooper 2000, p. 595.

- ^ Strode (1964), pp. 527–28.

- ^ Chesnut, Mary Boykin (1981). Mary Chesnut's Civil War. Yale University Press. p. 800. ISBN 978-0300029796.

- ^ Cashin 2006, p. 5.

- ^ a b "Varina Howell Davis (1826–1906)", Encyclopedia of Virginia, June 2, 2014; accessed June 29, 2015.

- ^ a b c Wyatt-Brown 1994, pp. 159–60.

- ^ Wyatt-Brown 1994, p. 165.

- ^ Wyatt-Brown 1994, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Davis, Varina (1890). "Jefferson Davis, A Memoir". New York: Belford Company. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ Cashin 2006, p. 7.

- ^ "Funeral of Mrs. Davis". New-York Tribune. October 18, 1906.

- ^ "Mrs. Jefferson Davis Dead at the Majestic". The New York Times. October 17, 1906.

- ^ "Mrs. Davis Now At Rest Beside Famous Husband in Hollywood Cemetery". Richmond Times-Dispatch. October 20, 1906. p. 1.

- ^ Gantt, Marlene (July 11, 2014). "Jewels embellish Varina Davis' sad tale". Dispatch Argus. Archived from the original on October 11, 2024. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "Hartnett T. Kane (1910-1984)". librarything.com. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ "Varina". Harper Collins. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

Further reading

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Davis, Varina Jefferson Davis, Ex-President of the Confederate States of America: A Memoir, by His Wife

Secondary sources

[edit]- Cashin, Joan (2006). First Lady of the Confederacy: Varina Davis's Civil War, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Luskey, Ashley Whitehead, A Debt of Honor: Elite Women's Rituals of Cultural Authority in the Confederate Capital (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6124. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6124

- Ross, Ishbel, First Lady of the South, The Life of Mrs. Jefferson Davis, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, 1958

- Rowland, Eron. Varina Howell, Wife of Jefferson Davis,, New York: The Macmillan Co., 1927 and 1931 (two volumes)

- Strode, Hudson (1955). Jefferson Davis, Volume I: American Patriot. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

- Strode, Hudson (1964). Jefferson Davis, Volume III: Tragic Hero. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company.

- Wyatt-Brown, Bertram (1994). The House of Percy: Honor, Melancholy and Imagination in a Southern Family, New York: Oxford University Press.

External links

[edit]- Varina Davis, First Lady Of The Confederate States Of America

- A stop on the Varina Davis trail route - 181 Highway 215 South, Happy Valley

Varina Davis

View on GrokipediaVarina Anne Banks Howell Davis (May 7, 1826 – October 16, 1906) was the second wife of Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America, and consequently the only First Lady of the Confederacy during the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865.[1][2] Born near Natchez to William B. Howell, a War of 1812 veteran and merchant with family ties spanning North and South, she received a classical education that included studies in Philadelphia.[3][2] She met the widowed Jefferson Davis, then a Mississippi planter and U.S. senator, at a Christmas gathering in 1843 and married him on February 26, 1845, at her family home "The Briars," overcoming initial opposition due to their eighteen-year age gap and his Yankee background.[1][4] The couple had six children, though only one daughter, Margaret, outlived Varina, with tragedies including the death of young son Joseph in a White House accident in 1864.[2][3] As First Lady in Richmond, she managed the Confederate White House, hosting levees and dinners that followed antebellum Washington protocols to foster Southern unity, while visiting hospitals and aiding relief efforts amid food shortages and social scrutiny over her Northern-influenced wit and independence.[1][2] Following the Confederacy's collapse, Varina endured her husband's imprisonment from 1865 to 1867, then resided with him in exile in Canada, Europe, and Memphis before settling at Beauvoir, Mississippi.[3][4] After Jefferson's death in 1889, she relocated to New York City, where she supported herself through journalism for outlets like The New York World, authored a two-volume memoir of her husband in 1890, and cultivated friendships across sectional lines, including with Julia Grant.[2][1] She died of pneumonia in New York and was buried beside her husband in Richmond's Hollywood Cemetery.[4][1]