Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Peninsula campaign

View on Wikipedia| Peninsula campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

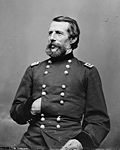

George B. McClellan and Joseph E. Johnston, respective commanders of the Union and Confederate armies in the Peninsula campaign | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| United States | Confederate States of America | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| George B. McClellan |

Joseph E. Johnston Gustavus Woodson Smith Robert E. Lee John B. Magruder | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Potomac | Army of Northern Virginia | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 23,119[7] | 29,298[7] | ||||||

| |||||||

The Peninsula campaign (also known as the Peninsular campaign) of the American Civil War was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March to July 1862, the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Major General George B. McClellan, was an amphibious turning movement against the Confederate States Army in Northern Virginia, intended to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond. Despite the fact that Confederate spy Thomas Nelson Conrad had obtained documents describing McClellan's battle plans from a double agent in the War Department, McClellan was initially successful against the equally cautious General Joseph E. Johnston, but the emergence of the more aggressive General Robert E. Lee turned the subsequent Seven Days Battles into a humiliating Union defeat.

McClellan landed his army at Fort Monroe and moved northwest, up the Virginia Peninsula. Confederate Brigadier General John B. Magruder's defensive position on the Warwick Line caught McClellan by surprise. His hopes for a quick advance foiled, McClellan ordered his army to prepare for a siege of Yorktown. Just before the siege preparations had been completed, the Confederates, now under the direct command of Johnston, began a withdrawal toward Richmond. The first heavy fighting of the campaign occurred during the Battle of Williamsburg in which the Union troops managed some tactical victories, but the Confederates continued their withdrawal. An amphibious flanking movement to Eltham's Landing was ineffective in cutting off the Confederate retreat. During the Battle of Drewry's Bluff, an attempt by the US Navy to reach Richmond by way of the James River was repulsed.

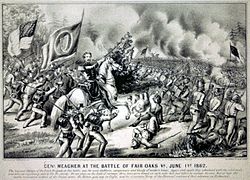

As McClellan's army reached the outskirts of Richmond, a minor battle occurred at Hanover Court House, but it was followed by a surprise attack by Johnston at the Battle of Seven Pines or Fair Oaks. The battle was inconclusive, with heavy casualties, but it had lasting effects on the campaign. Johnston was wounded by a Union artillery shell fragment on May 31 and replaced the next day by the more aggressive Robert E. Lee, who reorganized his army and prepared for offensive action in the final battles of June 25 to July 1, which are popularly known as the Seven Days Battles. The result was that the Union army was unable to enter Richmond, and both armies remained intact.

Background

[edit]Military situation

[edit]On August 20, 1861, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan formed the Army of the Potomac, with himself as its first commander.[8] During the summer and fall, McClellan brought a high degree of organization to his new army, and greatly improved its morale by his frequent trips to review and encourage his units. It was a remarkable achievement, in which he came to personify the Army of the Potomac and reaped the adulation of his men.[9] He created defenses for Washington that were almost impregnable, consisting of 48 forts and strong points, with 480 guns manned by 7,200 artillerists.[10]

On November 1, 1861, Gen. Winfield Scott retired and McClellan became general in chief of all the Union armies. The president expressed his concern about the "vast labor" involved in the dual role of army commander and general in chief, but McClellan responded, "I can do it all."[11]

On January 12, 1862, McClellan revealed his intentions to transport the Army of the Potomac by ship to Urbanna, Virginia, on the Rappahannock River, outflanking the Confederate forces near Washington, and proceeding 50 miles (80 km) overland to capture Richmond. On January 27, Lincoln issued an order that required all of his armies to begin offensive operations by February 22, Washington's birthday. On January 31, he issued a supplementary order for the Army of the Potomac to move overland to attack the Confederates at Manassas Junction and Centreville. McClellan immediately replied with a 22-page letter objecting in detail to the president's plan and advocating instead his Urbanna plan, which was the first written instance of the plan's details being presented to the president. Although Lincoln believed his plan was superior, he was relieved that McClellan finally agreed to begin moving, and reluctantly approved. On March 8, doubting McClellan's resolve, Lincoln called a council of war at the White House in which McClellan's subordinates were asked about their confidence in the Urbanna plan. They expressed their confidence to varying degrees. After the meeting, Lincoln issued another order, naming specific officers as corps commanders to report to McClellan (who had been reluctant to do so prior to assessing his division commanders' effectiveness in combat, even though this would have meant his direct supervision of twelve divisions in the field).[12][13]

Before McClellan could implement his plans, the Confederate forces under General Joseph E. Johnston withdrew from their positions before Washington on March 9, assuming new positions south of the Rappahannock, which completely nullified the Urbanna strategy. McClellan retooled his plan so that his troops would disembark at Fort Monroe, Virginia, and advance up the Virginia Peninsula to Richmond. However, McClellan came under extreme criticism from the press and the Congress when it was found that Johnston's forces had not only slipped away unnoticed, but had for months fooled the Union Army through the use of Quaker Guns.[14][15][16][17]

A further complication for the campaign planning was the emergence of the first Confederate ironclad warship, CSS Virginia, which threw Washington into a panic and made naval support operations on the James River seem problematic.[18] In the Battle of Hampton Roads (March 8–9, 1862), Virginia defeated wooden U.S. Navy ships blockading the harbor of Hampton Roads, Virginia, including the frigates USS Cumberland and USS Congress on March 8, calling into question the viability of any of the wooden ships in the world. The following day, the USS Monitor ironclad arrived at the scene and engaged with the Virginia, the famous first duel of the ironclads. The battle, although inconclusive, received worldwide publicity. After the battle, it was clear that ironclad ships were the future of naval warfare. Neither ship severely damaged the other; the only net result was keeping Virginia from attacking any more wooden ships.[19][20][21]

On March 11, 1862, Lincoln removed McClellan as general-in-chief, leaving him in command of only the Army of the Potomac, ostensibly so that McClellan would be free to devote all his attention to the move on Richmond. Although McClellan was assuaged by supportive comments Lincoln made to him, in time he saw the change of command very differently, describing it as a part of an intrigue "to secure the failure of the approaching campaign."[22][23]

Opposing forces

[edit]Union

[edit]| Union corps commanders |

|---|

|

The Army of the Potomac had approximately 50,000 men at Fort Monroe when McClellan arrived in late March, but this number grew to 121,500 before hostilities began. The army was organized into three corps and other units, as follows:[24]

- II Corps, Brig. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner commanding: divisions of Brig. Gens. Israel B. Richardson and John Sedgwick

- III Corps, Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman commanding: divisions of Brig. Gens. Fitz John Porter, Joseph Hooker, and Charles S. Hamilton

- IV Corps, Brig. Gen. Erasmus D. Keyes commanding: divisions of Brig. Gens. Darius N. Couch, William F. "Baldy" Smith, and Silas Casey

- 1st Division of the I Corps, Brig. Gen. William B. Franklin commanding

- Reserve infantry commanded by Brig. Gen. George Sykes

- Cavalry commanded by Brig. Gen. George Stoneman

- The garrison of Fort Monroe, 12,000 men under Maj. Gen. John E. Wool; Wool was quickly transferred to another department for duty in Baltimore after the War Department realized that he technically outranked McClellan.

Confederate

[edit]| Confederate wing commanders |

|---|

|

On the Confederate side, Johnston's Army of Northern Virginia (newly named as of March 14)[25] was organized into three wings, each composed of several brigades, as follows:[26]

- Left Wing, Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill commanding: brigades of Brig. Gen. Robert E. Rodes, Winfield S. Featherston, Jubal A. Early, and Gabriel J. Raines

- Center Wing, Maj. Gen. James Longstreet commanding: brigades of Brig. Gens. A. P. Hill, Richard H. Anderson, George E. Pickett, Cadmus M. Wilcox, Raleigh E. Colston, and Roger A. Pryor

- Right Wing, Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder commanding: division of Brig. Gen. Lafayette McLaws (brigades of Brig. Gens. Paul J. Semmes, Richard Griffith, Joseph B. Kershaw, and Howell Cobb) and division of Brig. Gen. David R. Jones (brigades of Brig. Gens. Robert A. Toombs and George T. Anderson)

- Reserve force commanded by Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith

- Cavalry commanded by Brig. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart

However, at the time the Army of the Potomac arrived, only Magruder's 11,000 men faced them on the Peninsula. The bulk of Johnston's force (43,000 men) were at Culpeper, 6,000 under Maj. Gen. Theophilus H. Holmes at Fredericksburg, and 9,000 under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger at Norfolk. In Richmond, General Robert E. Lee had returned from work on coastal fortifications in the Carolinas and on March 13 became the chief military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.[27]

Forces in the Shenandoah Valley played an indirect role in the campaign. Approximately 50,000 men under Maj. Gens. Nathaniel P. Banks and Irvin McDowell were engaged chasing a much smaller force under Stonewall Jackson in the Valley Campaign. Jackson's expert maneuvering and tactical success in small battles kept the Union men from reinforcing McClellan, much to his dismay. He had planned to have 30,000 under McDowell to join him.[28]

Magruder had prepared three defensive lines across the Peninsula. The first, about 12 miles (19 km) north of Fort Monroe, contained infantry outposts and artillery redoubts, but was insufficiently manned to prevent any Union advance. Its primary purpose was to shield information from the Union about a second line extending from Yorktown to Mulberry Island. This Warwick Line consisted of redoubts, rifle pits, and fortifications behind the Warwick River. By enlarging two dams on the river, the river was turned into a significant military obstacle in its own right. The third defensive line was a series of forts at Williamsburg, which waited unmanned for use by the army if it had to fall back from Yorktown.[29]

Initial movements

[edit]Movement to the Peninsula and the siege of Yorktown

[edit]

McClellan's army began to sail from Alexandria on March 17. It was an armada that dwarfed all previous American expeditions, transporting 121,500 men, 44 artillery batteries, 1,150 wagons, over 15,000 horses, and tons of equipment and supplies. An English observer remarked that it was the "stride of a giant."[30]

With the Virginia still in operation, the U.S. Navy could not assure McClellan that they could protect operations on either the James or the York, so his plan of amphibiously enveloping Yorktown was abandoned, and he ordered an advance up the Peninsula to begin April 4.[31][32][33]

On April 5, the IV Corps of Brig. Gen. Erasmus D. Keyes made initial contact with Confederate defensive works at Lee's Mill, an area McClellan expected to move through without resistance. Magruder, a fan of theatrics, set up a successful deception campaign. By moving one company in circles through a glen, he gained the appearance of an endless line of reinforcements marching to relieve him. He also spread his artillery very far apart and had it fire sporadically at the Union lines. Federals were convinced that his works were strongly held, reporting that an army of 100,000 was in their path. As the two armies fought an artillery duel, reconnaissance indicated to Keyes the strength and breadth of the Confederate fortifications, and he advised McClellan against assaulting them. McClellan ordered the construction of siege fortifications and brought his heavy siege guns to the front. In the meantime, Gen. Johnston brought reinforcements for Magruder.[34][35]

McClellan chose not to attack without more reconnaissance and ordered his army to entrench in works parallel to Magruder's and besiege Yorktown. McClellan reacted to Keyes's report, as well as to reports of enemy strength near the town of Yorktown, but he also received word that the I Corps, under Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell, would be withheld for the defense of Washington, instead of joining him on the Peninsula as McClellan had planned. In addition to the pressure of Jackson's Valley campaign, President Lincoln believed that McClellan had left insufficient force to guard Washington and that the general had been deceptive in his reporting of unit strengths, counting troops as ready to defend Washington when they were actually deployed elsewhere. McClellan protested that he was being forced to lead a major campaign without his promised resources, but he moved ahead anyway. For the next 10 days, McClellan's men dug while Magruder steadily received reinforcements. By mid April, Magruder commanded 35,000 men, barely enough to defend his line.[36][37][19][38]

Although McClellan doubted his numeric superiority over the enemy, he had no doubts about the superiority of his artillery. The siege preparations at Yorktown consisted of 15 batteries with more than 70 heavy guns. When fired in unison, these batteries would deliver over 7,000 pounds of ordnance onto the enemy positions with each volley.[39]

On April 16, Union forces probed a point in the Confederate line at Dam No. 1, on the Warwick River near Lee's Mill. Magruder realized the weakness of his position and ordered it strengthened. Three regiments under Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb, with six other regiments nearby, were improving their position on the west bank of the river overlooking the dam. McClellan became concerned that this strengthening might impede his installation of siege batteries.[40] He ordered Brig. Gen. William F. "Baldy" Smith, a division commander in the IV Corps, to "hamper the enemy" in completing their defensive works.[41][40]

At 3 p.m., four companies of the 3rd Vermont Infantry crossed the dam and routed the remaining defenders. Behind the lines, Cobb organized a defense with his brother, Colonel Thomas Cobb of the Georgia Legion, and attacked the Vermonters, who had occupied the Confederate rifle pits. Unable to obtain reinforcements, the Vermont companies withdrew across the dam, suffering casualties as they retreated. At about 5 p.m., Baldy Smith ordered the 6th Vermont to attack Confederate positions downstream from the dam while the 4th Vermont demonstrated at the dam itself. This maneuver failed as the 6th Vermont came under heavy Confederate fire and were forced to withdraw. Some of the wounded men were drowned as they fell into the shallow pond behind the dam.[41]

For the remainder of April, the Confederates, now at 57,000 and under the direct command of Johnston, improved their defenses while McClellan undertook the laborious process of transporting and placing massive siege artillery batteries, which he planned to deploy on May 5. Johnston knew that the impending bombardment would be difficult to withstand, so began sending his supply wagons in the direction of Richmond on May 3. Escaped slaves reported that fact to McClellan, who refused to believe them. He was convinced that an army whose strength he estimated as high as 120,000 would stay and fight. On the evening of May 3, the Confederates launched a brief bombardment of their own and then fell silent. Early the next morning, Heintzelman ascended in one of Thaddeus Lowe's observation balloons and found that the Confederate earthworks were empty.[42][43][44][45]

McClellan was stunned by the news. He sent cavalry under Brig. Gen. George Stoneman in pursuit and ordered Brig. Gen. William B. Franklin's division to reboard Navy transports, sail up the York River, and cut off Johnston's retreat.[46]

Battles

[edit]Williamsburg

[edit]By May 5, Johnston's army was making slow progress on muddy roads and Stoneman's cavalry was skirmishing with Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry, Johnston's rearguard. To give time for the bulk of his army to get free, Johnston detached part of his force to make a stand at a large earthen fortification, Fort Magruder, straddling the Williamsburg Road (from Yorktown), constructed earlier by Magruder. The Battle of Williamsburg was the first pitched battle of the Peninsula campaign, in which nearly 41,000 Union and 32,000 Confederates were engaged.[47]

Brig. Gen. Joseph Hooker's 2nd Division of the III Corps was the lead infantry in the Union Army advance. They assaulted Fort Magruder and a line of rifle pits and smaller fortifications that extended in an arc southwest from the fort, but were repulsed. Confederate counterattacks, directed by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, threatened to overwhelm Hooker's division, which had contested the ground alone since the early morning while waiting for the main body of the army to arrive. Hooker had expected Baldy Smith's division of the IV Corps, marching north on the Yorktown Road, to hear the sound of battle and come in on Hooker's right in support. However, Smith had been halted by Sumner more than a mile away from Hooker's position. He had been concerned that the Confederates would leave their fortifications and attack him on the Yorktown Road.[48]

Longstreet's men did leave their fortifications, but they attacked Hooker, not Smith or Sumner. The brigade of Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox applied strong pressure to Hooker's line. Hooker's retreating men were aided by the arrival of Brig. Gen. Philip Kearny's 3rd Division of the III Corps at about 2:30 p.m. Kearny ostentatiously rode his horse out in front of his picket lines to reconnoiter and urged his men forward by flashing his saber with his only arm. The Confederates were pushed off the Lee's Mill Road and back into the woods and the abatis of their defensive positions. There, sharp firefights occurred until late in the afternoon.[49][48]

Brig. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock's 1st Brigade of Baldy Smith's division, which had marched a few miles to the Federal right and crossed Cub's Creek at the point where it was dammed to form the Jones's Mill pond, began bombarding Longstreet's left flank around noon. Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill, commanding Longstreet's reserve force, had previously detached a brigade under Brig. Gen. Jubal A. Early and posted them on the grounds of the College of William & Mary. Splitting his command, Early led two of his four regiments through the woods without performing adequate reconnaissance and found that they emerged not on the enemy's flank, but directly in front of Hancock's guns, which occupied two abandoned redoubts. He personally led the 24th Virginia Infantry on a futile assault and was wounded by a bullet through the shoulder.[50]

Hancock had been ordered repeatedly by Sumner to withdraw his command back to Cub Creek, but he used the Confederate attack as an excuse to hold his ground. As the 24th Virginia charged, D. H. Hill emerged from the woods leading one of Early's other regiments, the 5th North Carolina. He ordered an attack before realizing the difficulty of his situation—Hancock's 3,400 infantrymen and eight artillery pieces significantly outnumbered the two attacking Confederate regiments, fewer than 1,200 men with no artillery support. He called off the assault after it had begun, but Hancock ordered a counterattack. After the battle, the counterattack received significant publicity as a major, gallant bayonet charge and McClellan's description of Hancock's "superb" performance gave him the nickname, "Hancock the Superb."[51]

Confederate casualties at Williamsburg were 1,682, Union 2,283. McClellan miscategorized his first significant battle as a "brilliant victory" over superior forces. However, the defense of Williamsburg was seen by the South as a means of delaying the Federals, which allowed the bulk of the Confederate army to continue its withdrawal toward Richmond.[52]

Eltham's Landing (or West Point)

[edit]After McClellan ordered Franklin's division to turn Johnston's army with an amphibious operation on the York River, it took two days just to board the men and equipment onto the ships, so Franklin was of no assistance to the Williamsburg action. But McClellan had high hopes for his turning movement, planning to send other divisions (those of Brig. Gens. Fitz John Porter, John Sedgwick, and Israel B. Richardson) by river after Franklin's. Their destination was Eltham's Landing on the south bank of the Pamunkey River across from West Point, a port on the York River, which was the terminus of the Richmond and York River Railroad. The landing was close to a key intersection on the road to New Kent Court House that was being used by Johnston's army on the afternoon of May 6.[53][54][55]

Franklin's men came ashore in light pontoon boats and built a floating wharf to unload artillery and supplies. The work was continued by torchlight through the night and the only enemy resistance was a few random shots fired by Confederate pickets on the bluff above the landing, ending at about 10 p.m.[54][56]

Johnston ordered Maj. Gen. G. W. Smith to protect the road to Barhamsville and Smith assigned the division of Brig. Gen. William H. C. Whiting and Hampton's Legion, under Col. Wade Hampton, to the task. On May 7, Franklin posted Brig. Gen. John Newton's brigade in the woods on either side of the landing road, supported in the rear by portions of two more brigades (Brig. Gens. Henry W. Slocum and Philip Kearny).[57] Newton's skirmish line was pushed back as Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood's Texas Brigade advanced, with Hampton to his right.[56][58]

As a second brigade followed Hood on his left, the Union troops retreated from the woods to the plain before the landing, seeking cover from the fire of Federal gunboats. Whiting employed artillery fire against the gunboats, but his guns had insufficient range, so he disengaged around 2 p.m. Union troops moved back into the woods after the Confederates left, but made no further attempt to advance. Although the action was tactically inconclusive, Franklin missed an opportunity to intercept the Confederate retreat from Williamsburg, allowing it to pass unmolested.[56]

Norfolk and Drewry's Bluff

[edit]President Lincoln witnessed part of the campaign, having arrived at Fort Monroe on May 6 in the company of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase on the Treasury Department's revenue cutter Miami. Lincoln believed that the city of Norfolk was vulnerable and that control of the James was possible, but McClellan was too busy at the front to meet with the president. Exercising his direct powers as commander in chief, Lincoln ordered naval bombardments of Confederate batteries in the area on May 8 and set off in a small boat with his two Cabinet secretaries to conduct a personal reconnaissance on shore. Troops under the command of Maj. Gen. John E. Wool, the elderly commander of Fort Monroe, occupied Norfolk on May 10, encountering little resistance.[59]

After the Confederate garrison at Norfolk was evacuated, Commodore Josiah Tattnall III knew that CSS Virginia had no home port and he could not navigate her deep draft through the shallow stretches of the James River toward Richmond, so she was scuttled on May 11 off Craney Island to prevent her capture. This opened the James River at Hampton Roads to Federal gunboats.[60][61][62]

The only obstacle that protected Richmond from a river approach was Fort Darling on Drewry's Bluff, overlooking a sharp bend on the river 7 miles (11 km) down river from the city. The Confederate defenders, including marines, sailors, and soldiers, were supervised by Cammander Ebenezer Farrand of the navy and by Captain Augustus H. Drewry of the army, the owner of the property that bore his name.[63][64] The eight cannons in the fort, including field artillery pieces and five naval guns, some salvaged from the Virginia, commanded the river for miles in both directions. Guns from the CSS Patrick Henry, including an 8-inch (200 mm) smoothbore, were just upriver and sharpshooters gathered on the river banks. An underwater obstruction of sunken steamers, pilings, debris, and other vessels connected by chains was placed just below the bluff, making it difficult for vessels to maneuver in the narrow river.[65]

On May 15, a detachment of the U.S. Navy's North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, under the command of Commander John Rodgers steamed up the James River from Fort Monroe to test the Richmond defenses. At 7:45 a.m., the USS Galena closed to within 600 yards (550 m) of the fort and anchored, but before she could open fire, two Confederate rounds pierced the lightly armored vessel. The battle lasted over three hours and during that time, Galena remained almost stationary and took 45 hits. Her crew reported casualties of 14 dead or mortally wounded and 10 injured. Monitor was also a frequent target, but her heavier armor withstood the blows. Contrary to some reports, the Monitor, despite its squat turret, did not have difficulty bringing its guns to bear and fired steadily against the fort.[66] The USS Naugatuck withdrew when her 100-pounder Parrott rifle exploded. The two wooden gunboats remained safely out of range of the big guns, but the captain of the USS Port Royal was wounded by a sharpshooter. Around 11 a.m. the Union ships withdrew to City Point.[67][65][64]

The massive fort on Drewry's Bluff had blunted the Union advance just 7 miles (11 km) short of the Confederate capital.[68] Rodgers reported to McClellan that it was feasible for the Navy to land troops as close as 10 miles (16 km) from Richmond, but the Union Army never took advantage of this observation.[64][69]

Armies converge on Richmond

[edit]Johnston withdrew his 60,000 men into the Richmond defenses. Their defensive line began at the James River at Drewry's Bluff and extended counterclockwise so that his center and left were behind the Chickahominy River, a natural barrier in the spring when it turned the broad plains to the east of Richmond into swamps. Johnston's men burned most of the bridges over the Chickahominy and settled into strong defensive positions north and east of the city. McClellan positioned his 105,000-man army to focus on the northeast sector, for two reasons. First, the Pamunkey River, which ran roughly parallel to the Chickahominy, offered a line of communication that could enable McClellan to get around Johnston's left flank. Second, McClellan anticipated the arrival of McDowell's I Corps, scheduled to march south from Fredericksburg to reinforce his army, and thus needed to protect their avenue of approach.[70][71][72]

The Army of the Potomac pushed slowly up the Pamunkey, establishing supply bases at Eltham's Landing, Cumberland Landing, and White House Landing. White House, the plantation of W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee, son of General Robert E. Lee, became McClellan's base of operations. Using the Richmond and York River Railroad, McClellan could bring his heavy siege artillery to the outskirts of Richmond. He moved slowly and deliberately, reacting to faulty intelligence that led him to believe the Confederates outnumbered him significantly. By the end of May, the army had built bridges across the Chickahominy and was facing Richmond, straddling the river, with one third of the Army south of the river, two thirds north. (This disposition, which made it difficult for one part of the army to reinforce the other quickly, would prove to be a significant problem in the upcoming Battle of Seven Pines).[73][74][43]

| New Union corps commanders |

|---|

|

On May 18, McClellan reorganized the Army of the Potomac in the field and promoted two major generals to corps command: Fitz John Porter to the new V Corps and William B. Franklin to the VI Corps. The army had 105,000 men in position northeast of the city, outnumbering Johnston's 60,000, but faulty intelligence from the detective Allan Pinkerton on McClellan's staff caused the general to believe that he was outnumbered two to one. Numerous skirmishes between the lines of the armies occurred from May 23 to May 26. Tensions were high in the city, particularly following the earlier sounds of the naval gun battle at Drewry's Bluff.[75][71]

Hanover Court House

[edit]While skirmishing occurred all along the line between the armies, McClellan heard a rumor that a Confederate force of 17,000 was moving to Hanover Court House, north of Mechanicsville. If this were true, it would threaten the army's right flank and complicate the arrival of McDowell's reinforcements. A Union cavalry reconnaissance adjusted the estimate of the enemy strength to be 6,000, but it was still cause for concern. McClellan ordered Porter and his V Corps to deal with the threat.[73][76]

Porter departed on his mission at 4 a.m. on May 27 with his 1st Division, under Brig. Gen. George W. Morell, the 3rd Brigade of Brig. Gen. George Sykes's 2nd Division, under Col. Gouverneur K. Warren, and a composite brigade of cavalry and artillery led by Brig. Gen. William H. Emory, altogether about 12,000 men. The Confederate force, which actually numbered about 4,000 men, was led by Col. Lawrence O'Bryan Branch. They had departed from Gordonsville to guard the Virginia Central Railroad, taking up position at Peake's Crossing, 4 miles (6.4 km) southwest of the courthouse, near Slash Church. Another Confederate brigade was stationed 10 miles (16 km) north at Hanover Junction.[77][73]

Porter's men approached Peake's Crossing in a driving rain. At about noon on May 27, his lead element skirmished briskly with the Confederates until Porter's main body arrived, driving the outnumbered Confederates up the road in the direction of the courthouse. Porter set out in pursuit with most of his force, leaving three regiments to guard the New Bridge and Hanover Court House Roads intersection. This movement exposed the rear of Porter's command to attack by the bulk of Branch's force, which Porter had mistakenly assumed was at Hanover Court House.[78][79]

Branch also made a poor assumption—that Porter's force was significantly smaller than it turned out to be—and attacked. The initial assault was repulsed, but Martindale's force was eventually almost destroyed by the heavy fire. Porter quickly dispatched the two regiments back to the Kinney Farm. The Confederate line broke under the weight of thousands of new troops and they retreated back through Peake's Crossing to Ashland.[80][81]

The estimates of Union casualties at Hanover Court House vary, from 355 (62 killed, 233 wounded, 70 captured) to 397. The Confederates left 200 dead on the field and 730 were captured by Porter's cavalry. McClellan claimed that Hanover Court House was yet another "glorious victory over superior numbers" and judged that it was "one of the handsomest things of the war."[82] However, the reality of the outcome was that superior (Union) numbers won the day in a disorganized fight, characterized by misjudgments on both sides. The right flank of the Union army remained secure, although technically the Confederates at Peake's Crossing had not intended to threaten it. And McDowell's Corps did not need its roads kept clear because it never arrived—the defeat of Union forces at the First Battle of Winchester by Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley caused the Lincoln administration to recall McDowell to Fredericksburg.[83][82][81][84]

A greater impact than the actual casualties, according to Stephen W. Sears, was the effect on McClellan's preparedness for the next major battle, at Seven Pines and Fair Oaks four days later. During the absence of Porter, McClellan was reluctant to move more of his troops south of the Chickahominy, making his left flank a more attractive target for Johnston. He was also confined to bed, ill with a flare-up of his chronic malaria.[85]

Seven Pines (or Fair Oaks)

[edit]

Johnston knew that he could not survive a massive siege of Richmond and decided to attack McClellan. His original plan was to attack the Union right flank, north of the Chickahominy River, before McDowell's corps, marching south from Fredericksburg, could arrive. However, on May 27, Johnston learned that McDowell's corps had been diverted to the Shenandoah Valley and would not be reinforcing the Army of the Potomac. He decided against attacking across his own natural defense line, the Chickahominy, and planned to capitalize on the Union army's straddle of the river by attacking the two corps south of the river, leaving them isolated from the other three corps north of the river.[86]

If executed correctly, Johnston would engage two thirds of his army (22 of its 29 infantry brigades, about 51,000 men) against the 33,000 men in the III and IV Corps. The Confederate attack plan was complex, calling for the divisions of A.P. Hill and Magruder to engage lightly and distract the Union forces north of the river, while Longstreet, commanding the main attack south of the river, was to converge on Keyes from three directions. The plan had an excellent potential for initial success because the division of the IV Corps farthest forward, manning the earthworks a mile west of Seven Pines, was that of Brig. Gen. Silas Casey, 6,000 men who were the least experienced in Keyes's corps. If Keyes could be defeated, the III Corps, to the east, could then be pinned against the Chickahominy and overwhelmed.[87][88][89]

The complex plan was mismanaged from the start. Johnston issued orders that were vague and contradictory and failed to inform all of his subordinates about the chain of command. On Longstreet's part, he either misunderstood his orders or chose to modify them without informing Johnston, changing his route of march to collide with Hill's, which not only delayed the advance, but limited the attack to a narrow front with only a fraction of its total force. Exacerbating the problems on both sides was a severe thunderstorm on the night of May 30, which flooded the river, destroyed most of the Union bridges, and turned the roads into morasses of mud.[90][91][92][93]

The attack got off to a bad start on May 31 when Longstreet marched down the Charles City Road and turned onto the Williamsburg Road instead of the Nine Mile Road. Huger's orders had not specified a time that the attack was scheduled to start and he was not awakened until he heard a division marching nearby. Johnston and his second-in-command, Smith, unaware of Longstreet's location or Huger's delay, waited at their headquarters for word of the start of the battle. Five hours after the scheduled start, at 1 p.m., D.H. Hill became impatient and sent his brigades forward against Casey's division.[94][95][96]

Casey's line buckled with some men retreating, but fought fiercely for possession of their earthworks, resulting in heavy casualties on both sides. The Confederates only engaged four brigades of the thirteen on their right flank that day, so they did not hit with the power that they could have concentrated on this weak point in the Union line. Casey sent for reinforcements but Keyes was slow in responding. Eventually the mass of Confederates broke through, seized a Union redoubt, and Casey's men retreated to the second line of defensive works at Seven Pines.[97][98]

Hill, now strengthened by reinforcements from Longstreet, hit the secondary Union line near Seven Pines around 4:40 p.m. Hill organized a flanking maneuver to attack Keyes's right flank, which collapsed the Federal line back to the Williamsburg Road. Johnston went forward on the Nine Mile Road with three brigades of Whiting's division and encountered stiff resistance near Fair Oaks Station, the right flank of Keyes's line. Soon heavy Union reinforcements arrived. Brig. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner, II Corps commander, heard the sounds of battle from his position north of the river. On his own initiative, he dispatched a division under Brig. Gen. John Sedgwick over the sole remaining bridge. The treacherous "Grapevine Bridge" was near collapse on the swollen river, but the weight of the crossing troops helped to hold it steady against the rushing water. After the last man had crossed safely, the bridge collapsed and was swept away. Sedgwick's men provided the key to resisting Whiting's attack.[99][100][101]

At dusk, Johnston was wounded and evacuated to Richmond. G.W. Smith assumed temporary command of the army. Smith, plagued with ill health, was indecisive about the next steps for the battle and made a bad impression on President Davis and General Lee, Davis's military adviser. After the end of fighting the following day, Davis replaced Smith with Lee as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia.[102][103][101]

On June 1, the Confederates under Smith renewed their assaults against the Federals, who had brought up more reinforcements and fought from strong positions, but made little headway. The fighting ended about 11:30 a.m. when the Confederates withdrew. McClellan arrived on the battlefield from his sick bed at about this time, but the Union Army did not counterattack.[104]

Both sides claimed victory with roughly equal casualties—Union casualties were 5,031 (790 killed, 3,594 wounded, 647 captured or missing), Confederate 6,134 (980 killed, 4,749 wounded, 405 captured or missing).[105] McClellan's advance on Richmond was halted and the Army of Northern Virginia fell back into the Richmond defensive works. The battle was frequently remembered by the Union soldiers as the Battle of Fair Oaks Station because that is where they did their best fighting, whereas the Confederates, for the same reason, called it Seven Pines.[106]

The Seven Days Battles

[edit]

Despite claiming victory at Seven Pines, McClellan was shaken by the experience. He redeployed all of his army except for the V Corps south of the river, and although he continued to plan for a siege and the capture of Richmond, he lost the strategic initiative and never regained it.[107]

Lee used the month-long pause in McClellan's advance to fortify the defenses of Richmond and extend them south to the James River at Chaffin's Bluff. On the south side of the James River, defensive lines were built south to a point below Petersburg. The total length of the new defensive line was about 30 miles (48 km). To buy time to complete the new defensive line and prepare for an offensive, Lee repeated the tactic of making a small number of troops seem larger than they really were. McClellan was also unnerved by Jeb Stuart's audacious (but otherwise militarily pointless) cavalry ride completely around the Union army (June 13–15).[108]

The second phase of the Peninsula campaign took a negative turn for the Union when Lee launched fierce counterattacks just east of Richmond in the Seven Days Battles (June 25 – July 1, 1862).[109] Although none of these battles were significant Confederate tactical victories (and the Battle of Malvern Hill on the last day was a significant Confederate defeat), the tenacity of Lee's attacks and the sudden appearance of Stonewall Jackson's "foot cavalry" on his western flank unnerved McClellan, who pulled his forces back to a base on the James River.[110] Lincoln later ordered the army to return to the Washington, D.C., area to support Maj. Gen. John Pope's army in the northern Virginia campaign and the Second Battle of Bull Run.[111] The Virginia Peninsula was relatively quiet until May 1864, when Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler again invaded as part of the Bermuda Hundred campaign.[112]

Aftermath

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ ORA 11(3), 184

- ^ ORA 11(3), 238

- ^ ORA 11(3), 312; Further information: Official Records, Series I, Volume V, page 13.

- ^ Newton, Joseph E. Johnston and the Defence of Richmond, Appedix 2

- ^ Harsh, Confederate Tide Rising, Appendix 2C

- ^ ORA 11(3), 645

- ^ a b Livermore, Numbers and Losses in the Civil War, various pages

- ^ Beatie, Birth of Command, p. 480; Eicher, High Commands, pp. 372, 856.

- ^ Sears, Young Napoleon, p. 111.

- ^ Sears, Young Napoleon, p. 116.

- ^ McPherson, p. 360.

- ^ Sears, Young Napoleon, pp. 140–141, 149, 160

- ^ Beatie, McClellan's First Campaign, pp. 21–22, 108

- ^ Sears, Young Napoleon, pp. 168–169

- ^ Burton, p. 2

- ^ Rafuse, p. 201

- ^ Beatie, McClellan's First Campaign, p. 64.

- ^ Beatie, McClellan's First Campaign, p. 103

- ^ a b Kennedy, p. 88

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 195–199

- ^ Salmon, pp. 72–76

- ^ Beatie, McClellan's First Campaign, pp. 98–101

- ^ Sears, Young Napoleon, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 214–215; Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 359–363.

- ^ Eicher, High Commands, pp. 323, 889; Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 46.

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, p. 215; Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 364–367.

- ^ Esposito, text to map 39.

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 257–267.

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 26, 70.

- ^ Sears, Young Napoleon, pp. 167–169.

- ^ Beatie, McClellan's First Campaign, pp. 291–295

- ^ Burton, p. 4

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 39

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 42–43

- ^ Burton, pp. 14–15, 20

- ^ Burton, p. 15

- ^ Salmon, p. 76

- ^ Rafuse, p. 205

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 58

- ^ a b Burton, p. 20

- ^ a b Salmon, pp. 76–77

- ^ Rafuse, p. 211

- ^ a b Esposito, map 41

- ^ Burton, p. 24

- ^ Salmon, p. 79

- ^ Salmon, p. 80

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 70

- ^ a b Salmon, p. 82

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 74–78

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 78–80

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 79–83

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 82

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, p. 270

- ^ a b Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 85

- ^ Salmon, p. 83

- ^ a b c Salmon, p. 85

- ^ Webb, p. 82

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 86

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 89–92

- ^ Esposito, map 42

- ^ Salmon, p. 86

- ^ Burton, p. 5

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 93

- ^ a b c Eicher, Longest Night, p. 273

- ^ a b Salmon, p. 87

- ^ Richmond Battlefield Park signage

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 93–94

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 94

- ^ Rafuse, p. 213

- ^ Salmon, p. 88

- ^ a b Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 273–274

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 95–97

- ^ a b c Salmon, p. 90

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 104–106

- ^ Rafuse, p. 212

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 113–114

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, p. 275

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 114

- ^ Salmon, pp. 90–91

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 116

- ^ a b Salmon, p. 91

- ^ a b Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 117

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, 276

- ^ Kennedy, p. 92

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 117, 129

- ^ Salmon, pp. 20–21

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 118–120

- ^ Miller, p. 21

- ^ Salmon, pp. 91–92

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 120

- ^ Miller, pp. 21–22

- ^ Downs, pp. 675–676

- ^ Salmon, p. 92

- ^ Miller, p. 22

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, p. 276

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 121–123

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, p. 277

- ^ Salmon, p. 93

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 277–278

- ^ Miller, p. 23

- ^ a b Salmon, p. 94

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 145

- ^ Miller, p. 24

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, pp. 142–145

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 147

- ^ Sears, Gates of Richmond, p. 149

- ^ Miller, pp. 25–60

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 280–281

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, p. 281

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 296–297

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 326–327

- ^ Eicher, Longest Night, pp. 680–682

References

[edit]- Bailey, Ronald H., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Forward to Richmond: McClellan's Peninsular Campaign. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1983. ISBN 0-8094-4720-7.

- Beatie, Russel H. Army of the Potomac: Birth of Command, November 1860 – September 1861. New York: Da Capo Press, 2002. ISBN 0-306-81141-3.

- Beatie, Russel H. Army of the Potomac: McClellan's First Campaign, March – May 1862. New York: Savas Beatie, 2007. ISBN 978-1-932714-25-8.

- Burton, Brian K. The Peninsula & Seven Days: A Battlefield Guide. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8032-6246-1.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide[permanent dead link]. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- Miller, William J. The Battles for Richmond, 1862. National Park Service Civil War Series. Fort Washington, PA: U.S. National Park Service and Eastern National, 1996. ISBN 0-915992-93-0.

- National Park Service battle descriptions

- Rafuse, Ethan S. McClellan's War: The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-253-34532-4.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- Sears, Stephen W. George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon. New York: Da Capo Press, 1988. ISBN 0-306-80913-3.

- Sears, Stephen W. To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign. New York: Ticknor and Fields, 1992. ISBN 0-89919-790-6.

- Webb, Alexander S. The Peninsula: McClellan's Campaign of 1862. Secaucus, NJ: Castle Books, 2002. ISBN 0-7858-1575-9. First published 1885.

Further reading

[edit]- Crenshaw, Doug. Richmond Shall Not Be Given Up: The Seven Days' Battles, June 25–July 1, 1862. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2017. ISBN 978-1-61121-355-3.

- Edge, Frederick Milnes (1895). Major-General McClellan and the campaign on the Yorktown Peninsula. London: Trübner & Co.

- Gallagher, Gary W., ed. The Richmond Campaign of 1862: The Peninsula & the Seven Days. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8078-2552-2.

- Killblane, Richard E. White House Landing Staff Ride, U.S. Army Transportation Corps.

- Marks, James Junius (1864). The Peninsula campaign in Virginia, or, Incidents and scenes on the battlefields and in Richmond. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott.

- Martin, David G. The Peninsula Campaign March–July 1862. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1992. ISBN 978-0-938289-09-8.

- Tidball, John C. The Artillery Service in the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1865. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-1594161490.

- Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 1, The Eastern Theater. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-253-36453-1.

- Wheeler, Richard. Sword Over Richmond: An Eyewitness History of McClellan's Peninsula Campaign. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1986. ISBN 0-06-015529-9.

External links

[edit]Peninsula campaign

View on GrokipediaBackground and Strategic Context

Union Objectives and Planning

The primary Union objective in the Peninsula Campaign was to capture Richmond, the Confederate capital, by advancing through southeastern Virginia, thereby aiming to deliver a decisive blow to the Confederacy and potentially shorten the Civil War.[2] Major General George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, advocated for this strategy following Union setbacks in 1861, arguing that a direct overland advance from Washington would expose federal forces to entrenched Confederate defenses and high casualties.[4] Instead, McClellan proposed leveraging Union naval superiority for an amphibious flanking maneuver, transporting troops to Fort Monroe and marching up the narrow Peninsula between the York and James Rivers to approach Richmond from the southeast.[2] Planning commenced in late 1861 and early 1862 amid pressure from President Abraham Lincoln for offensive action, culminating in McClellan's formal submission of a revised Peninsula plan, which Lincoln approved in early March 1862 on the condition that sufficient troops remain to defend Washington, D.C. On March 11, 1862, Lincoln relieved McClellan of his role as general-in-chief to focus solely on field command, though the campaign proceeded as outlined.[4] Embarkation began on March 17, 1862, with the Army of the Potomac—numbering approximately 121,500 troops, 14,592 horses, 1,150 wagons, and 44 artillery batteries—transported by steamer from the Potomac River area to Fort Monroe in the largest amphibious operation in North American history up to that point.[2] [4] McClellan's planning emphasized logistical thoroughness and cautious tactics, including the establishment of secure supply lines supported by naval gunboats and the organization of the army into four corps under major generals Samuel P. Heintzelman, Erasmus D. Keyes, Edwin V. Sumner, and William B. Franklin to improve command efficiency over the large force.[2] The strategy anticipated a methodical advance, potentially involving sieges against fortified positions like Yorktown, to minimize direct assaults and exploit numerical superiority, though McClellan's persistent overestimation of Confederate troop strengths—often claiming forces double the actual numbers—influenced his deliberate pacing.[4] This approach reflected McClellan's engineering background and preference for preparation over rapid maneuvers, setting the stage for the campaign's execution starting April 4, 1862.[2]Confederate Defensive Posture

The Confederate defensive posture in the Peninsula Campaign emphasized fortified delays and strategic withdrawals to preserve forces for the defense of Richmond, leveraging terrain advantages such as rivers and swamps while compensating for numerical inferiority. Following Union landings at Fort Monroe in early March 1862, Major General John Bankhead Magruder commanded the Army of the Peninsula, numbering approximately 13,000 men, who fortified a 12-mile line of earthworks stretching from Yorktown to Gloucester Point across the York River. These defenses incorporated pre-existing Revolutionary War-era fortifications enhanced with redoubts, rifle pits, and dams on the Warwick River that flooded adjacent lowlands, creating a natural barrier that restricted Union flanking maneuvers.[7][4] Magruder employed deception tactics, including the use of "Quaker guns"—logs painted to resemble artillery—and repeated marches of his limited troops in view of Union observers to simulate a much larger force, successfully inducing Major General George B. McClellan to initiate a prolonged siege on April 5, 1862. General Joseph E. Johnston, assuming command of the consolidated Army of Northern Virginia on April 12, reinforced the Yorktown position with his main force of around 55,000 men transferred from northern Virginia, yet recognized the vulnerability of static defenses against McClellan's superior artillery and numbers exceeding 100,000. Johnston's strategy prioritized avoiding decisive engagements in untenable positions, advocating a mobile defense that traded space for time to concentrate interior lines nearer Richmond.[2][4] This posture reflected broader Confederate doctrine under President Jefferson Davis, who favored contesting Union advances at intermediate points despite Johnston's preference for earlier retreats to stronger ground around the capital. On May 3, 1862, Johnston ordered a nighttime evacuation of Yorktown, withdrawing intact to fallback lines including the Williamsburg defenses, thereby delaying the Union advance by nearly a month without suffering catastrophic losses. The maneuver preserved Confederate combat effectiveness for subsequent operations, such as the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5, while allowing time to bolster Richmond's perimeter fortifications.[7][2]Broader Military Situation

In spring 1862, the Union pursued a multi-front strategy to overwhelm Confederate defenses, with significant advances in the Western Theater complementing the Peninsula Campaign in the East. Union forces under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant repelled a Confederate offensive at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6–7, suffering heavy casualties but securing a tactical victory that enabled deeper penetration into Tennessee and Mississippi.[8] This was followed by the naval capture of New Orleans on April 25 by Flag Officer David G. Farragut, which gave the Union control of the South's largest port and severed Confederate access to the lower Mississippi River.[9] By late May, Union Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck's siege forced the Confederate evacuation of Corinth, Mississippi, on May 29–30, consolidating Federal gains in northern Mississippi and disrupting Rebel rail communications.[10] In the East, beyond the Peninsula, Confederate Lt. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign from March to June diverted critical Union reinforcements from Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's advance on Richmond. Jackson's rapid maneuvers defeated three Union columns totaling over 50,000 men while inflicting fewer than 1,500 Confederate casualties, prompting President Abraham Lincoln to withhold Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell's 30,000-man corps near Fredericksburg out of concern for Washington's security.[11][2] This Valley distraction, combined with Confederate interior lines, allowed the Rebels to concentrate forces against McClellan despite numerical disadvantages. Overall, Union successes in the West—yielding control of key rivers and cities—contrasted with the stalled Eastern offensive, straining Confederate resources but highlighting the benefits of their defensive concentration around Richmond. The broader Federal strategy aimed to exploit superior manpower and naval power across theaters, though coordination challenges and Confederate mobility limited decisive breakthroughs.[6]Commanders and Opposing Forces

Union Leadership and Army of the Potomac

Major General George B. McClellan served as the overall commander of the Army of the Potomac for the Peninsula Campaign, having assumed command of the army following the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861 and organized its training and structure.[4][2] On March 3, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln directed the formation of five corps within the army, appointing commanders despite McClellan's preference for retaining divisional organization.[12] The Army of the Potomac, exceeding 120,000 troops strong, underwent the largest amphibious operation of the war, with transports departing Alexandria starting March 17, 1862, for Fort Monroe at the Peninsula's tip.[2] For the campaign, McClellan employed II Corps under Brigadier General Edwin V. Sumner, III Corps under Brigadier General Samuel P. Heintzelman, IV Corps under Brigadier General Erasmus D. Keyes, and V Corps under Major General Fitz John Porter, while I Corps under Major General Irvin McDowell remained in northern Virginia to bolster defenses around Washington, D.C.[12][13] In April 1862, McClellan formed a provisional VI Corps under Brigadier General William B. Franklin from elements of III Corps to support operations.[2] McClellan grouped these corps into wings for maneuver: IV Corps as the left wing advancing south of the Chickahominy River, III and V Corps in the center north of the river, and II Corps as the right wing, with VI Corps in reserve.[13] Each corps comprised 2–3 divisions, supported by artillery reserves under Colonel Henry J. Hunt and cavalry under Brigadier General Philip St. George Cooke, though McClellan consistently overestimated Confederate strength, influencing cautious advances.[12][2]

| Corps | Commander | Key Divisions |

|---|---|---|

| II Corps | Brig. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner | Richardson, Sedgwick |

| III Corps | Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman | Porter (later detached), Hooker, Hamilton (Kearny) |

| IV Corps | Brig. Gen. Erasmus D. Keyes | Couch, Smith, Casey |

| V Corps | Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter | Morell, Sykes, McCall (Pennsylvania Reserves) |

| VI Corps (provisional) | Brig. Gen. William B. Franklin | Smith, Slocum |

Confederate Leadership and Army of Northern Virginia

General Joseph E. Johnston commanded the Confederate Department of Northern Virginia, overseeing the defense against the Union advance during the Peninsula Campaign from March to late May 1862.[14] After withdrawing approximately 40,000 troops from Manassas Junction on March 9, 1862, to evade encirclement by superior Union numbers, Johnston repositioned his forces southward to protect Richmond, concentrating reinforcements at Yorktown by early May.[15] There, he assumed field command from Major General John Bankhead Magruder on May 4, 1862, following the Confederate evacuation of the Yorktown lines, amid strategic disagreements with President Jefferson Davis over the timing and extent of withdrawals to prevent Union forces from outflanking entrenched positions.[16] [15] The Army of Northern Virginia, as the force was known under Johnston's predecessor organization, comprised roughly 55,000 to 60,000 effectives by mid-spring 1862, bolstered by units from various states including Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Mississippi.[17] Its structure featured a Right Wing under Major General James Longstreet, responsible for the primary defensive line east of Richmond; a Left Wing initially led by Magruder, who commanded about 13,600 troops at Yorktown with brigades under D.H. Hill and others conducting deception maneuvers to exaggerate Confederate numbers; and a Reserve division under Major General Gustavus W. Smith.[18] [19] Key subordinates included Brigadier General Robert E. Rodes in Hill's wing at Yorktown and Major General Daniel H. Hill, who directed operations on the left flank.[16] Johnston's leadership emphasized tactical retreats to consolidate forces, avoiding pitched battles against Major General George B. McClellan's larger Army of the Potomac until positioned advantageously near Richmond.[20] This approach culminated in the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, 1862, where Johnston directed an attack by Longstreet's and Smith's commands against isolated Union corps, but poor coordination and swampy terrain led to heavy casualties without decisive gains.[21] Severely wounded by artillery fire and a bullet during the engagement—sustaining injuries to his right shoulder and chest—Johnston was incapacitated, prompting Davis to relieve him on June 1, 1862, and appoint Robert E. Lee to command, marking the transition to more aggressive Confederate operations in the Seven Days Battles.[5] Johnston's caution preserved the army's strength but drew criticism from Davis for perceived reluctance to engage, reflecting underlying tensions over defensive versus offensive priorities in Confederate strategy.[15]Initial Movements and Yorktown

Amphibious Landing and Advance

The Union Army of the Potomac, under Major General George B. McClellan, executed the largest amphibious operation in American history up to that point by transporting its forces by water to Fort Monroe, Virginia, beginning on March 17, 1862. This movement involved over 120,000 men, along with extensive supplies, artillery, and equipment, shipped from Alexandria and Washington using a fleet of more than 100 vessels.[2][22] Fort Monroe, a Union stronghold since the war's outset, provided a secure base at the southern tip of the Virginia Peninsula, between the York and James Rivers, facilitating the logistical buildup without immediate opposition.[4] With the army concentrated at Fort Monroe by early April, McClellan initiated the overland advance northward up the Peninsula on April 4, 1862, aiming to outflank Confederate defenses and capture Richmond. The force, organized into five divisions under corps commanders Brigadier Generals Samuel P. Heintzelman, Erasmus D. Keyes, and Edwin V. Sumner, advanced in two primary wings: Heintzelman's Third Corps along the York River and Keyes's Fourth Corps nearer the James River, with Sumner's Second Corps in reserve.[23][4] Initial probes encountered Confederate outposts under Major General John B. Magruder, including skirmishes that pushed back pickets but revealed fortified lines at Yorktown by April 5.[24] The advance covered approximately 12 miles from Fort Monroe to the Warwick River line near Yorktown, where Confederate forces numbering around 13,000 held entrenched positions spanning from the York to the James. McClellan's caution, influenced by exaggerated reports of enemy strength, led to a halt short of assault, setting the stage for siege operations as reinforcements continued to arrive, swelling Union numbers to over 100,000 by late April.[5][4] This methodical progression prioritized securing supply lines via the rivers, leveraging Union naval superiority for protection against potential Confederate counterattacks.[25]Siege of Yorktown and Confederate Withdrawal

Union forces under Major General George B. McClellan reached the Confederate defenses at Yorktown, Virginia, on April 5, 1862, where Major General John B. Magruder's army held fortified lines originally constructed during the Revolutionary War and known as the Warwick Line. [26] [27] McClellan, estimating Confederate strength as formidable based on Magruder's demonstrations of troop movements that created an illusion of numerical superiority despite Magruder's actual force of around 13,000 men, chose not to launch a direct assault but instead initiated a formal siege, mirroring the tactics employed by his predecessor Winfield Scott in Mexico. [26] [24] Over the following weeks, McClellan methodically constructed parallels and advanced trenches while assembling a massive artillery train, including 101 siege guns such as 200-pounder Parrott rifles, 13-inch mortars, and 10-inch siege howitzers, supported by the Union's naval superiority that transported supplies and reinforcements efficiently. [7] [27] [28] On April 16, Union probes at Dam No. 1 along the Warwick River tested Confederate positions but were repulsed, confirming McClellan's caution and commitment to the siege approach amid his army's growth to over 100,000 effectives by late April. [26] [4] General Joseph E. Johnston, assuming command of Confederate forces in the Yorktown sector upon his arrival from Norfolk on April 22, recognized that the Union's artillery buildup would inflict unsustainable casualties on entrenched defenders lacking comparable ordnance, prompting him to prioritize maneuver over static defense to preserve his army of approximately 50,000-60,000 for battles closer to Richmond. [4] [2] Johnston ordered the evacuation to commence under cover of darkness on the night of May 3, 1862, with rear-guard actions delaying Union pursuit; Confederate troops systematically destroyed supplies, spiked guns, and withdrew up the Peninsula toward Williamsburg. [4] [6] McClellan, anticipating a bombardment to soften defenses for an assault planned for May 5, discovered the Confederate departure the morning of May 4 through reconnaissance and deserters, allowing his forces to occupy Yorktown unopposed but delaying the overall advance as he reorganized supply lines and pursued cautiously. [29] [24] The withdrawal, while tactically sound in avoiding a material disadvantage in a prolonged artillery duel, yielded the Peninsula's lower defenses to the Union and shifted the campaign's focus inland, where Confederate forces could contest McClellan's divided army across the Chickahominy River. [4] [2]

Intermediate Engagements

Battle of Williamsburg

The Battle of Williamsburg occurred on May 5, 1862, in York and James City Counties near Williamsburg, Virginia, as Union forces under Major General George B. McClellan pursued the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia retreating from Yorktown.[30][31] Elements of the Union III Corps under Brigadier General Joseph Hooker initially engaged the Confederate rear guard commanded by Major General James Longstreet, who held defensive positions anchored on Fort Magruder to delay the advance and protect General Joseph E. Johnston's main force withdrawing toward Richmond.[32][30] Brigadier General Edwin V. Sumner's II Corps reinforced Hooker later in the day, with Brigadier General Winfield Scott Hancock's brigade advancing on the Union right flank to exploit gaps in the Confederate line.[31][32] Heavy fighting erupted under rainy conditions, beginning with Hooker's division assaulting Confederate earthworks south of Fort Magruder around 7:00 a.m., but repeated attacks faltered against entrenched defenders supported by artillery, resulting in significant Union repulses in wooded areas and ravines known as the "Bloody Ravine."[30][31] Longstreet, facing local numerical inferiority in his rear guard of approximately 11,000–15,000 men against over 40,000 Union troops present, committed reinforcements including Brigadier General Jubal A. Early's brigade to counter Hancock's bold occupation of abandoned redoubts on the Confederate left, leading to intense hand-to-hand combat that Hancock's forces repelled after several hours.[31][30][32] The battle concluded with Confederate forces withdrawing under cover of darkness, having sustained the delaying action for nearly ten hours despite being outnumbered overall by Union strengths estimated at 40,768 to 41,000 against 31,823 to 32,000 Confederates in the vicinity.[30][32] Union casualties totaled 2,283 (456 killed, 1,410 wounded, 373 missing or captured), while Confederate losses were 1,560 to 1,703 (primarily killed and wounded).[30][31][32] Tactically inconclusive, the engagement succeeded for the Confederates in buying critical time for Johnston's army to escape without encirclement, though McClellan portrayed it as a Union victory in official reports, crediting Hancock's performance—earning him the moniker "Hancock the Superb"—while the delay minimally hindered the overall Union advance toward Richmond.[30][31][32]Eltham's Landing and Diversions

As Confederate forces under General Joseph E. Johnston withdrew from the Williamsburg line toward Richmond following the evacuation of Yorktown on May 4, 1862, Union Major General George B. McClellan sought to exploit the retreat by ordering a flanking maneuver up the York River.[4] On May 5, Brigadier General William B. Franklin's division of approximately 10,000 men from the VI Corps embarked on transports to land at Eltham's Landing, aiming to position Union forces across the Confederate line of retreat near the Pamunkey River confluence and potentially sever Johnston's route to the Chickahominy River.[33] This operation represented an amphibious effort to disrupt the Confederate withdrawal, though it arrived after the main Rebel army had already passed the area.[2] Franklin's troops began disembarking at Eltham's Landing on May 6, 1862, under observation by Confederate cavalry scouts.[34] The following morning, May 7, elements of Brigadier General Gustavus W. Smith's command, including brigades led by John B. Hood and Wade Hampton, launched attacks against the landing site to delay Union consolidation and protect the retreating army's flank.[33] Skirmishing intensified as Confederate forces probed Union positions, but Federal artillery and supporting fire from Union Navy gunboats repelled the assaults, allowing Franklin to secure a beachhead without significant territorial gains inland.[4] The engagement resulted in 186 Union casualties (28 killed, 120 wounded, and 38 missing) and 46 Confederate losses, marking a tactical Union hold but a strategic missed opportunity to interdict Johnston's forces.[2] Concurrent with Eltham's Landing, McClellan's broader strategy incorporated diversionary actions to fix Confederate attention, though these yielded limited results. Confederate responses, including Smith's brigade movements, functioned as tactical diversions to screen the main army's march, buying critical time for Johnston to consolidate south of the Chickahominy by May 8.[33] Franklin's division remained at Eltham until early June, conducting minor reconnaissance but failing to advance aggressively due to concerns over vulnerable supply lines and potential counterattacks, before rejoining the Army of the Potomac near White House Landing.[4] These efforts highlighted the challenges of coordinated amphibious operations in the Peninsula Campaign, where Union caution contrasted with Confederate mobility in covering their retreat.[2]Norfolk Campaign and Drewry's Bluff

Following the Confederate evacuation of Yorktown on May 4, 1862, the defenses around Norfolk, Virginia, under Major General Benjamin Huger, became untenable as reinforcements were redirected to bolster General Joseph E. Johnston's army near Richmond.[35] On May 10, Huger's approximately 9,000 troops withdrew inland toward Petersburg, destroying military stores, fortifications, and the Gosport Navy Yard (Norfolk Naval Shipyard), where they scuttled the ironclad CSS Virginia on May 11 to prevent its capture.[36] President Abraham Lincoln, observing from a Union gunboat, directed Brigadier General John E. Wool's 5,000-man division from Fort Monroe to occupy the lightly defended city; Wool's forces landed near Sewell's Point and entered Norfolk without resistance that same day, securing the port and denying the Confederacy a key naval base.[35] The fall of Norfolk cleared obstructions in Hampton Roads and the lower James River, enabling Union naval forces to support the Peninsula Campaign by threatening Richmond from the water.[37] On May 15, Captain John Rodgers' James River Flotilla—including the ironclads USS Monitor and USS Galena, wooden gunboats USS Aroostook and USS Port Royal, and the revenue cutter USS Naugatuck—advanced upriver toward the Confederate capital, supported by army transports carrying troops for potential landings.[38] However, eight miles below Richmond, the squadron encountered Confederate obstructions (sunken vessels and torpedoes, or early mines) and the strongly fortified Drewry's Bluff, known as Fort Darling, manned by about 300 sailors, marines, and soldiers under Commander Ebenezer Farrand with eight heavy guns, including 10-inch Columbiads.[37] The ensuing engagement lasted over three hours, with Union ships firing from long range but hampered by low gun elevations, soft riverbank mud preventing secure anchoring, and plunging fire from the bluff's heights.[38] The CSS Patrick Henry and CSS Jamestown provided supporting fire from the river, while Confederate shore batteries inflicted severe damage, particularly on the Galena, which absorbed over 40 hits and suffered 13 killed and 11 wounded.[37] Unable to breach the defenses or silence the guns, Rodgers withdrew after exhausting ammunition, with total Union casualties of 24 (including the Monitor's two killed and two wounded, its first combat losses).[38] Confederate losses numbered 15, including eight killed.[38] The repulse at Drewry's Bluff secured the James River approach to Richmond for the Confederacy until mid-1864, forcing Union commander Major General George B. McClellan to rely on overland advances across the Chickahominy River without direct naval gunfire support.[37] This outcome highlighted the effectiveness of elevated terrain and fixed fortifications against early ironclad warfare, though it did not prevent McClellan's ongoing siege preparations further up the peninsula.[38]Approach to Richmond

Hanover Court House

On May 27, 1862, during the Peninsula Campaign, Union Major General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac faced a divided position with the Chickahominy River separating its right wing under Major General Fitz John Porter's V Corps from the main body advancing toward Richmond.[39] Confederate Brigadier General Lawrence O'B. Branch's brigade, numbering approximately 4,100 men, had moved south from Hanover Court House to threaten the Union right flank and potentially link with Major General Thomas J. Jackson's forces in the Shenandoah Valley.[39] McClellan ordered Porter, with around 12,000 troops from the divisions of Brigadier Generals George W. Morell and George Sykes, to disperse Branch's command and secure the northern approaches for expected reinforcements from Irvin McDowell's corps near Fredericksburg.[39] Porter's column departed at 4:00 a.m., advancing northward along the Ashland Road, and encountered Confederate pickets before engaging Branch's divided forces near Peake's Turnout on the Virginia Central Railroad.[39] Branch, surprised and outnumbered, attempted to concentrate his brigades but faced coordinated Union assaults; Morell's infantry and artillery drove back Confederate positions at Slash Church and along the railroad, while Sykes' regulars supported the flanks.[39] The fighting lasted several hours, resulting in a decisive Union rout of Branch's brigade, which retreated northward with heavy losses, including over 200 killed and around 700 captured.[39] Union casualties totaled 355, comprising killed, wounded, and missing, while Confederate losses reached 746.[39] The victory neutralized the immediate threat to McClellan's right flank, preventing Confederate interference with supply lines and reinforcement routes, though McDowell's command was ultimately withheld due to Jackson's successes in the Valley Campaign.[39] Porter's success demonstrated effective maneuver against a smaller, isolated foe but diverted forces from the main advance on Richmond, contributing to later criticisms of McClellan's cautious strategy amid superior Confederate concentration under General Robert E. Lee.[39]Battle of Seven Pines