Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vertical loop

View on Wikipedia

The generic roller coaster vertical loop, also known as a loop-the-loop or a loop-de-loop, where a section of track causes the riders to complete a 360 degree turn, is the most basic of roller coaster inversions. At the top of the loop, riders are completely inverted.

History

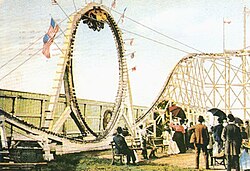

[edit]The vertical loop is not a recent roller coaster innovation. Its origins can be traced back to the 1850s when centrifugal railways were built in France and Great Britain.[1][2] The rides relied on centripetal forces to hold the car in the loop. One early looping coaster was shut down after an accident.[3] Later attempts to build a looping roller coaster were carried out during the late 19th century with the Flip Flap Railway at Sea Lion Park, designed by Roller coaster engineer Lina Beecher.[4] The ride was designed with a completely circular loop (rather than the teardrop shape used by many modern looping roller coasters), and caused neck injuries due to the intense G-forces pulled with the tight radius of the loop.[5][6]

The next attempt at building a looping roller coaster was in 1901 when Edwin Prescott built the Loop the Loop at Coney Island. This ride used the modern teardrop-shaped loop and a steel structure, however more people wanted to watch the attraction, rather than ride. In 1904, Beecher further redesigned the vertical loop to have an even more elliptical design with Olentangy Park's Loop-the-Loop. Vertical loops weren't attempted again until the design of Great American Revolution at Six Flags Magic Mountain, which opened in 1976. Its success depended largely on its clothoid-based (rather than circular) loop. The loop became a phenomenon, and many parks hastened to build roller coasters featuring them.[citation needed]

In 2000, a modern looping wooden roller coaster was built, the Son of Beast at Kings Island. Although the ride itself was made of wood, the loop was supported with steel structure. Due to maintenance issues however, the loop was removed at the end of the 2006 season. The loop was not the cause of the ride's issues, but was removed as a precautionary measure. Due to an unrelated issue in 2009, Son of Beast was closed until 2012, when Kings Island announced that it would be removed.[7][8]

On June 22, 2013, Six Flags Magic Mountain introduced Full Throttle, a steel launch coaster with a 160-foot (49 m) loop, the tallest in the world at the time of its opening.[9] As of 2016[update], the largest vertical loop is located on Flash, a roller coaster produced by Mack Rides at Lewa Adventure in Shaanxi, China.[10][11] The record is shared by a hypercoaster in Turkey's Land of Legends theme park (named 'Hyper Coaster'), built in 2018, which is identical to Flash at Lewa Adventure.[11][12]

Loops on non-roller coasters

[edit]In 2002, the Swiss company Klarer Freizeitanlagen AG began working on a safe design for a looping water slide.[13] Since then, multiple installations of the slide, named the AquaLoop and constructed by companies including Polin, Klarer, Aquarena and WhiteWater West, have appeared in many parks. This ride does not feature a vertical loop, instead using an inclined loop (a vertical loop tilted at an angle), which puts less force on the rider. AquaLoop slides feature a safety hatch, which can be opened by a rider in case they do not reach the highest point of the loop.

Physics/mechanics

[edit]

Most roller coaster loops are not circular in shape. A commonly used shape is the clothoid loop, which resembles an inverted tear drop and allows for less intense G-forces throughout the element for the rider.[14] The use of this shape was pioneered in 1976 on The New Revolution at Six Flags Magic Mountain, by Werner Stengel of leading coaster engineering firm Ing.-Büro Stengel GmbH.

On the way up, from the bottom to the top of the loop, gravity is in opposition to the direction of the cars and will slow the train. The train is slowest at the top of the loop. Once beyond the top, gravity helps to pull the cars down around the bend. If the loop's curvature is constant, the rider is subjected to the greatest force at the bottom. If the curvature of the track changes suddenly, as from level to a circular loop, the greatest force is imposed almost instantly . Gradual changes in curvature, as in the clothoid, reduce the force maximum (permitting more speed) and allow the rider time to cope safely with the changing force.[5]

This "gentling" runs somewhat contrary to the coaster's raison d'être. Schwarzkopf-designed roller coasters often feature near-circular loops (in case of Thriller even without any reduction of curvature between two almost perfectly circular loops) resulting in intense rides—a trademark for the designer.[citation needed]

It is rare for a roller coaster to stall in a vertical loop, although this has happened before. The Psyké Underground coaster (then known as Sirocco) at Walibi Belgium once stranded riders upside-down for several hours. The design of the trains and the rider restraint system (in this case, a simple lap bar) prevented any injuries from occurring, and the riders were removed with the use of a cherry picker.[citation needed] A similar incident occurred on Demon at Six Flags Great America.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ Cartmell, Robert (1987). The Incredible Scream Machine: A History of the Roller Coaster. Popular Press. p. 156. ISBN 0-87972-342-4.

- ^ Timbs, John (1843). The Year-book of facts in science and art. London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co. p. 15.

centrifugal railway.

- ^ Roller Coaster History - Early History

- ^ "American Pioneers of Amusement, Part 2." Off the Leash. Published 10 July 2016. Accessed 5 May 2024. https://offtheleash.net/2016/07/10/american-pioneers-of-amusement-part-2/.

- ^ a b Tipler, Paul A.; Mosca, Gene (2008). Physics for Scientists and Engineers. Vol. Standard (6th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-1429201247. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Pearson, Will; Hattikudur, Mangesh; Koerth-Baker, Maggie (2005). Mental_Floss Presents Instant Knowledge. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0061747661. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ McClelland, Justin (July 27, 2012). "Kings Island to tear down Son of Beast". Dayton Daily News. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ "Son of Beast roller coaster to be removed to make room for future park expansion". Kings Island. July 27, 2012. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ MacDonald, Brady (7 March 2012). "Six Flags Magic Mountain spills plans for record-setting coaster". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ "Largest rollercoaster loop". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- ^ a b Marden, Duane. "Flash (Lewa Adventure)". Roller Coaster DataBase.

- ^ Marden, Duane. "Hyper Coaster (Land of Legends Theme Park)". Roller Coaster DataBase.

- ^ "EAP-Magazin.de: Special Feature2". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- ^ "Roller Coaster Loop Shapes". Archived from the original on 2007-08-27. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ^ "Roller coaster stuck in loop at Six Flags". The Telegraph Herald. Associated Press. 19 April 1998. Retrieved 27 August 2017.