Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Weightlessness

View on Wikipedia

Weightlessness is the complete or near-complete absence of the sensation of weight, i.e., zero apparent weight. It is also termed zero g-force, or zero-g (named after the g-force)[1] or, incorrectly, zero gravity.

Weight is a measurement of the force on an object at rest in a relatively strong gravitational field (such as on the surface of the Earth). These weight-sensations originate from contact with supporting floors, seats, beds, scales, and the like. A sensation of weight is also produced, even when the gravitational field is zero, when contact forces act upon and overcome a body's inertia by mechanical, non-gravitational forces- such as in a centrifuge, a rotating space station, or within an accelerating vehicle.

When the gravitational field is non-uniform, a body in free fall experiences tidal forces and is not stress-free. Near a black hole, such tidal effects can be very strong, leading to spaghettification. In the case of the Earth, the effects are minor, especially on objects of relatively small dimensions (such as the human body or a spacecraft) and the overall sensation of weightlessness in these cases is preserved. This condition is known as microgravity, and it prevails in orbiting spacecraft. Microgravity environment is more or less synonymous in its effects, with the recognition that gravitational environments are not uniform and g-forces are never exactly zero.

Weightlessness in Newtonian mechanics

[edit]

- Zero gravity and weightless

- Zero gravity but not weightless (spring is rocket propelled)

- Spring is in free fall and weightless

- Spring rests on a plinth and has both weight1 and weight2

In Newtonian physics the sensation of weightlessness experienced by astronauts is not the result of there being zero gravitational acceleration (as seen from the Earth), but of there being no g-force that an astronaut can feel because of the free-fall condition, and also there being zero difference between the acceleration of the spacecraft and the acceleration of the astronaut. Space journalist James Oberg explains the phenomenon this way:[2]

The myth that satellites remain in orbit because they have "escaped Earth's gravity" is perpetuated further (and falsely) by almost universal misuse of the word "zero gravity" to describe the free-falling conditions aboard orbiting space vehicles. Of course, this isn't true; gravity still exists in space. It keeps satellites from flying straight off into interstellar emptiness. What's missing is "weight", the resistance of gravitational attraction by an anchored structure or a counterforce. Satellites stay in space because of their tremendous horizontal speed, which allows them—while being unavoidably pulled toward Earth by gravity—to fall "over the horizon." The ground's curved withdrawal along the Earth's round surface offsets the satellites' fall toward the ground. Speed, not position or lack of gravity, keeps satellites in orbit around the Earth.

From the perspective of an observer not moving with the object (i.e. in an inertial reference frame) the force of gravity on an object in free fall is exactly the same as usual.[3] A classic example is an elevator car where the cable has been cut and it plummets toward Earth, accelerating at a rate equal to the 9.81 meters per second per second. In this scenario, the gravitational force is mostly, but not entirely, diminished; anyone in the elevator would experience an absence of the usual gravitational pull, however the force is not exactly zero. Since gravity is a force directed towards the center of the Earth, two balls a horizontal distance apart would be pulled in slightly different directions and would come closer together as the elevator dropped. Also, if they were some vertical distance apart the lower one would experience a higher gravitational force than the upper one since gravity diminishes according to the inverse square law. These two second-order effects are examples of micro gravity.[3]

Weightless and reduced weight environments

[edit]

Reduced weight in aircraft

[edit]Airplanes have been used since 1959 to provide a nearly weightless environment in which to train astronauts, conduct research, and film motion pictures. Such aircraft are commonly referred by the nickname "Vomit Comet".

To create a weightless environment, the airplane flies in a 10 km (6 mi) parabolic arc, first climbing, then entering a powered dive. During the arc, the propulsion and steering of the aircraft are controlled to cancel the drag (air resistance) on the plane out, leaving the plane to behave as if it were free-falling in a vacuum.

NASA's Reduced Gravity Aircraft

[edit]Versions of such airplanes have been operated by NASA's Reduced Gravity Research Program since 1973, where the unofficial nickname originated.[4] NASA later adopted the official nickname 'Weightless Wonder' for publication.[5] NASA's current Reduced Gravity Aircraft, "Weightless Wonder VI", a McDonnell Douglas C-9, is based at Ellington Field (KEFD), near Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center.

NASA's Microgravity University - Reduced Gravity Flight Opportunities Plan, also known as the Reduced Gravity Student Flight Opportunities Program, allows teams of undergraduates to submit a microgravity experiment proposal. If selected, the teams design and implement their experiment, and students are invited to fly on NASA's Vomit Comet.[citation needed]

European Space Agency A310 Zero-G

[edit]The European Space Agency (ESA) flies parabolic flights on a specially modified Airbus A310-300 aircraft[6] to perform research in microgravity. Along with the French CNES and the German DLR, they conduct campaigns of three flights over consecutive days, with each flight's about 30 parabolae totalling about 10 minutes of weightlessness. These campaigns are currently operated from Bordeaux - Mérignac Airport by Novespace,[7] a subsidiary of CNES; the aircraft is flown by test pilots from DGA Essais en Vol.

As of May 2010[update], the ESA has flown 52 scientific campaigns and also 9 student parabolic flight campaigns.[8] Their first Zero-G flights were in 1984 using a NASA KC-135 aircraft in Houston, Texas. Other aircraft used include the Russian Ilyushin Il-76 MDK before founding Novespace, then a French Caravelle and an Airbus A300 Zero-G.[9][10][11]

Commercial flights for public passengers

[edit]

Novespace created Air Zero G in 2012 to share the experience of weightlessness with 40 public passengers per flight, using the same A310 ZERO-G as for scientific experiences.[12] These flights are sold by Avico, are mainly operated from Bordeaux-Merignac, France, and intend to promote European space research, allowing public passengers to feel weightlessness. Jean-François Clervoy, Chairman of Novespace and ESA astronaut, flies with these one-day astronauts on board A310 Zero-G. After the flight, he explains the quest of space and talks about the 3 space travels he did along his career. The aircraft has also been used for cinema purposes, with Tom Cruise and Annabelle Wallis for the Mummy in 2017.[13]

The Zero Gravity Corporation operates a modified Boeing 727 which flies parabolic arcs to create 25–30 seconds of weightlessness.

Ground-based drop facilities

[edit]

Ground-based facilities that produce weightless conditions for research purposes are typically referred to as drop tubes or drop towers.

NASA's Zero Gravity Research Facility, located at the Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, is a 145 m vertical shaft, largely below the ground, with an integral vacuum drop chamber, in which an experiment vehicle can have a free fall for a duration of 5.18 seconds, falling a distance of 132 m. The experiment vehicle is stopped in approximately 4.5 m of pellets of expanded polystyrene, experiencing a peak deceleration rate of 65 g.

Also at NASA Glenn is the 2.2 Second Drop Tower, which has a drop distance of 24.1 m. Experiments are dropped in a drag shield in order to reduce the effects of air drag. The entire package is stopped in a 3.3 m tall air bag, at a peak deceleration rate of approximately 20 g. While the Zero Gravity Facility conducts one or two drops per day, the 2.2 Second Drop Tower can conduct up to twelve drops per day.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center hosts another drop tube facility that is 105 m tall and provides a 4.6 s free fall under near-vacuum conditions.[14]

Other drop facilities worldwide include:

- Micro-Gravity Laboratory of Japan (MGLAB) – 4.5 s free fall

- Experimental drop tube of the metallurgy department of Grenoble – 3.1 s free fall

- Fallturm Bremen University of Bremen in Bremen – 4.74 s free fall

- Einstein-Elevator at Leibniz University Hannover – 4.0 s free fall, 4.1 to 9 s for partial-g

- Queensland University of Technology Drop Tower – 2.0 s free fall

- National Centre for Combustion Research and Development at IIT-M – 2.5 s free fall [15]

Random Positioning Machines

[edit]Another ground-based approach to simulate weightlessness for biological samples is a "3D-clinostat," also called a random positioning machine. Unlike a regular clinostat, the random positioning machine rotates in two axes simultaneously and progressively establishes a microgravity-like condition via the principle of gravity-vector-averaging.

Neutral buoyancy

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2022) |

Orbits

[edit]

On the International Space Station (ISS), there are small g-forces come from tidal effects, gravity from objects other than the Earth, such as astronauts, the spacecraft, and the Sun, air resistance, and astronaut movements that impart momentum to the space station).[16][17][18] The symbol for microgravity, μg, was used on the insignias of Space Shuttle flights STS-87 and STS-107, because these flights were devoted to microgravity research in low Earth orbit.

Sub-Orbital flights

[edit]Over the years, biomedical research on the implications of space flight has become more prominent in evaluating possible pathophysiological changes in humans.[19] Sub-orbital flights seize the approximated weightlessness, or μg, in the low Earth orbit and represent a promising research model for short-term exposure. Examples of such approaches are the MASER, MAXUS, or TEXUS program run by the Swedish Space Corporation and the European Space Agency.

Orbital Motion

[edit]Orbital motion is a form of free fall.[3] Objects in orbit are not perfectly weightless due to several effects:

- Effects depending on relative position in the spacecraft:

- Because the force of gravity decreases with distance, objects with non-zero size will be subjected to a tidal force, or a differential pull, between the ends of the object nearest and furthest from the Earth. (An extreme version of this effect is spaghettification.) In a spacecraft in low Earth orbit (LEO), the centrifugal force is also greater on the side of the spacecraft furthest from the Earth. At a 400 km LEO altitude, the overall differential in g-force is approximately 0.384 μg/m.[20][3]

- Gravity between the spacecraft and an object within it may make the object slowly "fall" toward a more massive part of it. The acceleration is 0.007 μg for 1000 kg at 1 m distance.

- Uniform effects (which could be compensated):

- Though extremely thin, there is some air at orbital altitudes of 185 to 1,000 km. This atmosphere causes minuscule deceleration due to friction. This could be compensated by a small continuous thrust, but in practice the deceleration is only compensated from time to time, so the tiny g-force of this effect is not eliminated.

- The effects of the solar wind and radiation pressure are similar, but directed away from the Sun. Unlike the effect of the atmosphere, it does not reduce with altitude.

- Other Effects:

- Routine crew activity: Due to the conservation of momentum, any crew member aboard a spacecraft pushing off a wall causes the spacecraft to move in the opposite direction.

- Structural Vibration: Stress enacted on the hull of the spacecraft results in the spacecraft bending, causing apparent acceleration.

Weightlessness at the center of a planet

[edit]If an object were to travel to the center of a spherical planet unimpeded by the planet's materials, it would achieve a state of weightlessness upon arriving at the center of the planet's core. This is because the mass of the surrounding planet is exerting an equal gravitational pull in all directions from the center, canceling out the pull of any one direction, establishing a space with no gravitational pull.[21]

Absence of gravity

[edit]A "stationary" micro-g environment[22] would require travelling far enough into deep space so as to reduce the effect of gravity by attenuation to almost zero. This is simple in conception but requires travelling a very large distance, rendering it highly impractical. For example, to reduce the gravity of the Earth by a factor of one million, one needs to be at a distance of 6 million kilometres from the Earth, but to reduce the gravity of the Sun to this amount, one has to be at a distance of 3.7 billion kilometres. This is not impossible, but it has only been achieved thus far by four interstellar probes: (Voyager 1 and 2 of the Voyager program, and Pioneer 10 and 11 of the Pioneer program.) At the speed of light it would take roughly three and a half hours to reach this micro-gravity environment (a region of space where the acceleration due to gravity is one-millionth of that experienced on the Earth's surface). To reduce the gravity to one-thousandth of that on Earth's surface, however, one needs only to be at a distance of 200,000 km.

| Location | Gravity due to | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth | Sun | rest of Milky Way | ||

| Earth's surface | 9.81 m/s2 | 6 mm/s2 | 200 pm/s2 = 6 mm/s/yr | 9.81 m/s2 |

| Low Earth orbit | 9 m/s2 | 6 mm/s2 | 200 pm/s2 | 9 m/s2 |

| 200,000 km from Earth | 10 mm/s2 | 6 mm/s2 | 200 pm/s2 | up to 12 mm/s2 |

| 6×106 km from Earth | 10 μm/s2 | 6 mm/s2 | 200 pm/s2 | 6 mm/s2 |

| 3.7×109 km from Earth | 29 pm/s2 | 10 μm/s2 | 200 pm/s2 | 10 μm/s2 |

| Voyager 1 (17×109 km from Earth) | 1 pm/s2 | 500 nm/s2 | 200 pm/s2 | 500 nm/s2 |

| 0.1 light-year from Earth | 400 am/s2 | 200 pm/s2 | 200 pm/s2 | up to 400 pm/s2 |

At a distance relatively close to Earth (less than 3000 km), gravity is only slightly reduced. As an object orbits a body such as the Earth, gravity is still attracting objects towards the Earth and the object is accelerated downward at almost 1g. Because the objects are typically moving laterally with respect to the surface at such immense speeds, the object will not lose altitude because of the curvature of the Earth. When viewed from an orbiting observer, other close objects in space appear to be floating because everything is being pulled towards Earth at the same speed, but also moving forward as the Earth's surface "falls" away below. All these objects are in free fall, not zero gravity.

Compare the gravitational potential at some of these locations.

Health effects

[edit]

Following the advent of space stations that can be inhabited for long periods, exposure to weightlessness has been demonstrated to have some deleterious effects on human health.[23][24] Humans are well-adapted to the physical conditions at the surface of the Earth. In response to an extended period of weightlessness, various physiological systems begin to change and atrophy. Though these changes are usually temporary, long-term health issues can result.

The most common problem experienced by humans in the initial hours of weightlessness is known as space adaptation syndrome or SAS, commonly referred to as space sickness. Symptoms of SAS include nausea and vomiting, vertigo, headaches, lethargy, and overall malaise.[25] The first case of SAS was reported by cosmonaut Gherman Titov in 1961. Since then, roughly 45% of all people who have flown in space have suffered from this condition. The duration of space sickness varies, but in no case has it lasted for more than 72 hours, after which the body adjusts to the new environment. NASA jokingly measures SAS using the "Garn scale", named for United States Senator Jake Garn, whose SAS during STS-51-D was the worst on record. Accordingly, one "Garn" is equivalent to the most severe possible case of SAS.[26]

The most significant adverse effects of long-term weightlessness are muscle atrophy (see Reduced muscle mass, strength and performance in space for more information) and deterioration of the skeleton, or spaceflight osteopenia.[25] These effects can be minimized through a regimen of exercise,[27] such as cycling for example. Astronauts subject to long periods of weightlessness wear pants with elastic bands attached between waistband and cuffs to compress the leg bones and reduce osteopenia.[28] Other significant effects include fluid redistribution (causing the "moon-face" appearance typical of pictures of astronauts in weightlessness),[28][29] changes in the cardiovascular system as blood pressures and flow velocities change in response to a lack of gravity, a decreased production of red blood cells, balance disorders, and a weakening of the immune system.[30] Lesser symptoms include loss of body mass, nasal congestion, sleep disturbance, excess flatulence, and puffiness of the face. These effects begin to reverse quickly upon return to the Earth.

In addition, after long space flight missions, astronauts may experience vision changes.[31][32][33][34][35] Such eyesight problems may be a major concern for future deep space flight missions, including a crewed mission to the planet Mars.[31][32][33][34][36] Exposure to high levels of radiation may influence the development of atherosclerosis.[37] Clots in the internal jugular vein have recently been detected inflight.[38]

On December 31, 2012, a NASA-supported study reported that human spaceflight may harm the brains of astronauts and accelerate the onset of Alzheimer's disease.[39][40][41] In October 2015, the NASA Office of Inspector General issued a health hazards report related to human spaceflight, including a human mission to Mars.[42][43]

Space motion sickness

[edit]

Space motion sickness (SMS) is thought to be a subtype of motion sickness that plagues nearly half of all astronauts who venture into space.[44] SMS, along with facial stuffiness from headward shifts of fluids, headaches, and back pain, is part of a broader complex of symptoms that comprise space adaptation syndrome (SAS).[45] SMS was first described in 1961 during the second orbit of the fourth crewed spaceflight when the cosmonaut Gherman Titov aboard the Vostok 2, described feeling disoriented with physical complaints mostly consistent with motion sickness. It is one of the most studied physiological problems of spaceflight but continues to pose a significant difficulty for many astronauts. In some instances, it can be so debilitating that astronauts must sit out from their scheduled occupational duties in space – including missing out on a spacewalk they have spent months training to perform.[46] In most cases, however, astronauts will work through the symptoms even with degradation in their performance.[47]

Despite their experiences in some of the most rigorous and demanding physical maneuvers on earth, even the most seasoned astronauts may be affected by SMS, resulting in symptoms of severe nausea, projectile vomiting, fatigue, malaise (feeling sick), and headache.[47] These symptoms may occur so abruptly and without any warning that space travelers may vomit suddenly without time to contain the emesis, resulting in strong odors and liquid within the cabin which may affect other astronauts.[47] Some changes to eye movement behaviors might also occur as a result of SMS.[48] Symptoms typically last anywhere from one to three days upon entering weightlessness, but may recur upon reentry to Earth's gravity or even shortly after landing. SMS differs from terrestrial motion sickness in that sweating and pallor are typically minimal or absent and gastrointestinal findings usually demonstrate absent bowel sounds indicating reduced gastrointestinal motility.[49]

Even when the nausea and vomiting resolve, some central nervous system symptoms may persist which may degrade the astronaut's performance.[49] Graybiel and Knepton proposed the term "sopite syndrome" to describe symptoms of lethargy and drowsiness associated with motion sickness in 1976.[50] Since then, their definition has been revised to include "...a symptom complex that develops as a result of exposure to real or apparent motion and is characterized by excessive drowsiness, lassitude, lethargy, mild depression, and reduced ability to focus on an assigned task."[51] Together, these symptoms may pose a substantial threat (albeit temporary) to the astronaut who must remain attentive to life and death issues at all times.

SMS is most commonly thought to be a disorder of the vestibular system that occurs when sensory information from the visual system (sight) and the proprioceptive system (posture, position of the body) conflicts with misperceived information from the semicircular canals and the otoliths within the inner ear. This is known as the 'neural mismatch theory' and was first suggested in 1975 by Reason and Brand.[52] Alternatively, the fluid shift hypothesis suggests that weightlessness reduces the hydrostatic pressure on the lower body causing fluids to shift toward the head from the rest of the body. These fluid shifts are thought to increase cerebrospinal fluid pressure (causing back aches), intracranial pressure (causing headaches), and inner ear fluid pressure (causing vestibular dysfunction).[53]

Despite a multitude of studies searching for a solution to the problem of SMS, it remains an ongoing problem for space travel. Most non-pharmacological countermeasures such as training and other physical maneuvers have offered minimal benefit. Thornton and Bonato noted, "Pre- and inflight adaptive efforts, some of them mandatory and most of them onerous, have been, for the most part, operational failures."[54] To date, the most common intervention is promethazine, an injectable antihistamine with antiemetic properties, but sedation can be a problematic side effect.[55] Other common pharmacological options include metoclopramide, as well as oral and transdermal application of scopolamine, but drowsiness and sedation are common side effects for these medications as well.[53]

Musculoskeletal effects

[edit]In the space (or microgravity) environment the effects of unloading varies significantly among individuals, with sex differences compounding the variability.[56] Differences in mission duration, and the small sample size of astronauts participating in the same mission also adds to the variability to the musculoskeletal disorders that are seen in space.[57] In addition to muscle loss, microgravity leads to increased bone resorption, decreased bone mineral density, and increased fracture risks. Bone resorption leads to increased urinary levels of calcium, which can subsequently lead to an increased risk of nephrolithiasis.[58]

In the first two weeks that the muscles are unloaded from carrying the weight of the human frame during space flight, whole muscle atrophy begins. Postural muscles contain more slow fibers, and are more prone to atrophy than non-postural muscle groups.[57] The loss of muscle mass occurs because of imbalances in protein synthesis and breakdown. The loss of muscle mass is also accompanied by a loss of muscle strength, which was observed after only 2–5 days of spaceflight during the Soyuz-3 and Soyuz-8 missions.[57] Decreases in the generation of contractile forces and whole muscle power have also been found in response to microgravity.

To counter the effects of microgravity on the musculoskeletal system, aerobic exercise is recommended. This often takes the form of in-flight cycling.[57] A more effective regimen includes resistive exercises or the use of a penguin suit[57] (contains sewn-in elastic bands to maintain a stretch load on antigravity muscles), centrifugation, and vibration.[58] Centrifugation recreates Earth's gravitational force on the space station, in order to prevent muscle atrophy. Centrifugation can be performed with centrifuges or by cycling along the inner wall of the space station.[57] Whole body vibration has been found to reduce bone resorption through mechanisms that are unclear. Vibration can be delivered using exercise devices that use vertical displacements juxtaposed to a fulcrum, or by using a plate that oscillates on a vertical axis.[59] The use of beta-2 adrenergic agonists to increase muscle mass, and the use of essential amino acids in conjunction with resistive exercises have been proposed as pharmacologic means of combating muscle atrophy in space.[57]

Cardiovascular effects

[edit]Next to the skeletal and muscular system, the cardiovascular system is less strained in weightlessness than on Earth and is de-conditioned during longer periods spent in space.[60] In a regular environment, gravity exerts a downward force, setting up a vertical hydrostatic gradient. When standing, some 'excess' fluid resides in vessels and tissues of the legs. In a micro-g environment, with the loss of a hydrostatic gradient, some fluid quickly redistributes toward the chest and upper body; sensed as 'overload' of circulating blood volume.[61] In the micro-g environment, the newly sensed excess blood volume is adjusted by expelling excess fluid into tissues and cells (12-15% volume reduction) and red blood cells are adjusted downward to maintain a normal concentration (relative anemia).[61] In the absence of gravity, venous blood will rush to the right atrium because the force of gravity is no longer pulling the blood down into the vessels of the legs and abdomen, resulting in increased stroke volume.[62] These fluid shifts become more dangerous upon returning to a regular gravity environment as the body will attempt to adapt to the reintroduction of gravity. The reintroduction of gravity again will pull the fluid downward, but now there would be a deficit in both circulating fluid and red blood cells. The decrease in cardiac filling pressure and stroke volume during the orthostatic stress due to a decreased blood volume is what causes orthostatic intolerance.[63] Orthostatic intolerance can result in temporary loss of consciousness and posture, due to the lack of pressure and stroke volume.[64] Some animal species have evolved physiological and anatomical features (such as high hydrostatic blood pressure and closer heart place to head) which enable them to counteract orthostatic blood pressure.[65][66] More chronic orthostatic intolerance can result in additional symptoms such as nausea, sleep problems, and other vasomotor symptoms as well.[67]

Many studies on the physiological effects of weightlessness on the cardiovascular system are done in parabolic flights. It is one of the only feasible options to combine with human experiments, making parabolic flights the only way to investigate the true effects of the micro-g environment on a body without traveling into space.[68] Parabolic flight studies have provided a broad range of results regarding changes in the cardiovascular system in a micro-g environment. Parabolic flight studies have increased the understanding of orthostatic intolerance and decreased peripheral blood flow suffered by astronauts returning to Earth. Due to the loss of blood to pump, the heart can atrophy in a micro-g environment. A weakened heart can result in low blood volume, low blood pressure and affect the body's ability to send oxygen to the brain without the individual becoming dizzy.[69] Heart rhythm disturbances have also been seen among astronauts, but it is unclear whether this was a result of pre-existing conditions or an effect of the micro-g environment.[70] One current countermeasure includes drinking a salt solution, which increases the viscosity of blood and would subsequently increase blood pressure, which would mitigate post micro-g environment orthostatic intolerance. Another countermeasure includes administration of midodrine, which is a selective alpha-1 adrenergic agonist. Midodrine produces arterial and venous constriction resulting in an increase in blood pressure by baroreceptor reflexes.[71]

Effects on non-human organisms

[edit]Russian scientists have observed differences between cockroaches conceived in space and their terrestrial counterparts. The space-conceived cockroaches grew more quickly, and also grew up to be faster and tougher.[72]

Chicken eggs that are put in microgravity two days after fertilization appear not to develop properly, whereas eggs put in microgravity more than a week after fertilization develop normally.[73]

A 2006 Space Shuttle experiment found that Salmonella typhimurium, a bacterium that can cause food poisoning, became more virulent when cultivated in space.[74] On April 29, 2013, scientists in Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, funded by NASA, reported that, during spaceflight on the International Space Station, microbes seem to adapt to the space environment in ways "not observed on Earth" and in ways that "can lead to increases in growth and virulence".[75]

Under certain test conditions, microbes have been observed to thrive in the near-weightlessness of space[76] and to survive in the vacuum of outer space.[77][78]

Commercial applications

[edit]

High-quality crystals

[edit]While not yet a commercial application, there has been interest in growing crystals in micro-g, as in a space station or automated artificial satellite through Low-gravity process engineering, in an attempt to reduce crystal lattice defects.[79] Such defect-free crystals may prove useful for certain microelectronic applications and also to produce crystals for subsequent X-ray crystallography.

In 2017, an experiment on the ISS was conducted to crystallize the monoclonal antibody therapeutic Pembrolizumab, where results showed more uniform and homogenous crystal particles compared to ground controls.[80] Such uniform crystal particles can allow for the formulation of more concentrated, low-volume antibody therapies, something which can make them suitable for subcutaneous administration, a less invasive approach compared to the current prevalent method of intravenous administration.[81]

-

Comparison of boiling of water under Earth's gravity (1 g, left) and microgravity (right). The source of heat is in the lower part of the photograph.

-

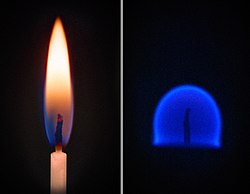

A comparison between the combustion of a candle on Earth (left) and in a microgravity environment, such as that found on the ISS (right).

-

Comparison of insulin crystals growth in outer space (left) and on Earth (right).

-

Liquids may also behave differently than on Earth, as demonstrated in this video

See also

[edit]- Artificial gravity

- Astronauts

- Clinostat

- Commercial use of space

- Effect of spaceflight on the human body

- ESA Scientific Research on the International Space Station

- European Low Gravity Research Association (ELGRA)

- G-jitter

- Microgravity University

- Reduced-gravity aircraft

- Scientific research on the International Space Station

- Space adaptation syndrome

- Space manufacturing

- Space medicine

- Vomit Comet

References

[edit]- ^ "Weightlessness and Its Effect on Astronauts". Space.com. 16 December 2017.

The sensation of weightlessness, or zero gravity, happens when the effects of gravity are not felt.

- ^ Oberg, James (May 1993). "Space myths and misconceptions". Omni. 15 (7). Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- ^ a b c d Chandler, David (May 1991). "Weightlessness and Microgravity" (PDF). The Physics Teacher. 29 (5): 312–13. Bibcode:1991PhTea..29..312C. doi:10.1119/1.2343327.

- ^ Reduced Gravity Research Program

- ^ "Loading..." www.nasaexplores.com. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ "Zero-G flying means high stress for an old A310". Flightglobal.com. 2015-03-23. Archived from the original on 2017-08-21. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- ^ "Novespace: microgravity, airborne missions". www.novespace.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ European Space Agency. "Parabolic Flight Campaigns". ESA Human Spaceflight web site. Archived from the original on 2012-05-26. Retrieved 2011-10-28.

- ^ European Space Agency. "A300 Zero-G". ESA Human Spaceflight web site. Retrieved 2006-11-12.

- ^ European Space Agency. "Next campaign". ESA Human Spaceflight web site. Retrieved 2006-11-12.

- ^ European Space Agency. "Campaign Organisation". ESA Human Spaceflight web site. Retrieved 2006-11-12.

- ^ "French astronaut performs "Moonwalk" on parabolic flight - Air & Cosmos - International". Air & Cosmos - International. Archived from the original on 2017-08-21. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- ^ "Tom Cruise defies gravity in Novespace ZERO-G A310". Archived from the original on 2017-08-21. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- ^ "Marshall Space Flight Center Drop Tube Facility". nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 19 September 2000. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ Kumar, Amit (2018). "The 2.5 s Microgravity Drop Tower at National Centre for Combustion Research and Development (NCCRD), Indian Institute of Technology Madras". Microgravity Science and Technology. 30 (5): 663–673. Bibcode:2018MicST..30..663V. doi:10.1007/s12217-018-9639-0.

- ^ Chandler, David (May 1991). "Weightlessness and Microgravity" (PDF). The Physics Teacher. 29 (5): 312–13. Bibcode:1991PhTea..29..312C. doi:10.1119/1.2343327.

- ^ Karthikeyan KC (September 27, 2015). "What Are Zero Gravity and Microgravity, and What Are the Sources of Microgravity?". Geekswipe. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ Oberg, James (May 1993). "Space myths and misconceptions – space flight". OMNI. 15 (7): 38ff.

- ^ Afshinnekoo, Ebrahim; Scott, Ryan T.; MacKay, Matthew J.; Pariset, Eloise; Cekanaviciute, Egle; Barker, Richard; Gilroy, Simon; Hassane, Duane; Smith, Scott M.; Zwart, Sara R.; Nelman-Gonzalez, Mayra; Crucian, Brian E.; Ponomarev, Sergey A.; Orlov, Oleg I.; Shiba, Dai (November 2020). "Fundamental Biological Features of Spaceflight: Advancing the Field to Enable Deep-Space Exploration". Cell. 183 (5): 1162–1184. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.050. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 8441988. PMID 33242416.

- ^ Bertrand, Reinhold (1998). Conceptual Design and Flight Simulation of Space Stations. Herbert Utz Verlag. p. 57. ISBN 978-3-89675-500-1.

- ^ Baird, Christopher S. (4 October 2013). "What would happen if you fell into a hole that went through the center of the earth?". Science Questions with Surprising Answers. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ Depending on distance, "stationary" is meant relative to Earth or the Sun.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (27 January 2014). "Beings Not Made for Space". New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 January 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ Stepanek, Jan; Blue, Rebecca S.; Parazynski, Scott (2019-03-14). Longo, Dan L. (ed.). "Space Medicine in the Era of Civilian Spaceflight". New England Journal of Medicine. 380 (11): 1053–1060. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1609012. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 30865799. S2CID 76667295.

- ^ a b Kanas, Nick; Manzey, Dietrich (2008). "Basic Issues of Human Adaptation to Space Flight". Space Psychology and Psychiatry. Space Technology Library. Vol. 22. pp. 15–48. Bibcode:2008spp..book.....K. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6770-9_2. ISBN 978-1-4020-6769-3.

- ^ "NASA - Johnson Space Center History" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2012-05-10., pg 35, Johnson Space Center Oral History Project, interview with Dr. Robert Stevenson:

"Jake Garn was sick, was pretty sick. I don't know whether we should tell stories like that. But anyway, Jake Garn, he has made a mark in the Astronaut Corps because he represents the maximum level of space sickness that anyone can ever attain, and so the mark of being totally sick and totally incompetent is one Garn. Most guys will get maybe to a tenth Garn, if that high. And within the Astronaut Corps, he forever will be remembered by that."

- ^ Kelly, Scott (2017). Endurance: A Year in Space, a Lifetime of Discovery. With Margaret Lazarus Dean. Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-5247-3159-5.

One of the nice things about living in space is that exercise is part of your job ... If I don't exercise six days a week for at least a couple of hours a day, my bones will lose significant mass - 1 percent each month ... Our bodies are smart about getting rid of what's not needed, and my body has started to notice that my bones are not needed in zero gravity. Not having to support our weight, we lose muscle as well.

- ^ a b "Health Fitness Archived 2012-05-19 at the Wayback Machine", Space Future

- ^ "The Pleasure of Spaceflight Archived 2012-02-21 at the Wayback Machine", Toyohiro Akiyama, Journal of Space Technology and Science, Vol.9 No.1 spring 1993, pp.21-23

- ^ Buckey, Jay C. (2006). Space Physiology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513725-5.

- ^ a b Mader, T. H.; et al. (2011). "Optic Disc Edema, Globe Flattening, Choroidal Folds, and Hyperopic Shifts Observed in Astronauts after Long-duration Space Flight". Ophthalmology. 118 (10): 2058–2069. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.021. PMID 21849212. S2CID 13965518.

- ^ a b Puiu, Tibi (November 9, 2011). "Astronauts' vision severely affected during long space missions". zmescience.com. Archived from the original on November 10, 2011. Retrieved February 9, 2012.

- ^ a b "Video News - CNN". CNN. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ a b Space Staff (13 March 2012). "Spaceflight Bad for Astronauts' Vision, Study Suggests". Space.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ^ Kramer, Larry A.; et al. (13 March 2012). "Orbital and Intracranial Effects of Microgravity: Findings at 3-T MR Imaging". Radiology. 263 (3): 819–827. doi:10.1148/radiol.12111986. PMID 22416248. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ^ Fong, MD, Kevin (12 February 2014). "The Strange, Deadly Effects Mars Would Have on Your Body". Wired. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Abbasi, Jennifer (20 December 2016). "Do Apollo Astronaut Deaths Shine a Light on Deep Space Radiation and Cardiovascular Disease?". JAMA. 316 (23): 2469–2470. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.12601. PMID 27829076.

- ^ Auñón-Chancellor, Serena M.; Pattarini, James M.; Moll, Stephan; Sargsyan, Ashot (2020-01-02). "Venous Thrombosis during Spaceflight". New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (1): 89–90. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1905875. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 31893522.

- ^ Cherry, Jonathan D.; Frost, Jeffrey L.; Lemere, Cynthia A.; Williams, Jacqueline P.; Olschowka, John A.; O'Banion, M. Kerry (2012). "Galactic Cosmic Radiation Leads to Cognitive Impairment and Increased Aβ Plaque Accumulation in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease". PLOS ONE. 7 (12) e53275. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...753275C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053275. PMC 3534034. PMID 23300905.

- ^ Staff (January 1, 2013). "Study Shows that Space Travel is Harmful to the Brain and Could Accelerate Onset of Alzheimer's". SpaceRef. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ Cowing, Keith (January 3, 2013). "Important Research Results NASA Is Not Talking About (Update)". NASA Watch. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (October 29, 2015). "Report: NASA needs better handle on health hazards for Mars". AP News. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

- ^ Staff (October 29, 2015). "NASA's Efforts to Manage Health and Human Performance Risks for Space Exploration (IG-16-003)" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ Weerts, Aurélie P.; Vanspauwen, Robby; Fransen, Erik; Jorens, Philippe G.; Van de Heyning, Paul H.; Wuyts, Floris L. (2014-06-01). "Space Motion Sickness Countermeasures: A Pharmacological Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 85 (6): 638–644. doi:10.3357/asem.3865.2014. PMID 24919385.

- ^ "Space Motion Sickness (Space Adaptation)" (PDF). NASA. June 15, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ "Illness keeps astronaut from spacewalk". ABCNews. February 12, 2008. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c Thornton, William; Bonato, Frederick (2017). The Human Body and Weightlessness. SpringerLink. p. 32. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32829-4. ISBN 978-3-319-32828-7.

- ^ Alexander, Robert G.; Macknik, Stephen L.; Martinez-Conde, Susana (2019). "Microsaccades in Applied Environments: Real-World Applications of Fixational Eye Movement Measurements". Journal of Eye Movement Research. 12 (6). doi:10.16910/jemr.12.6.15. PMC 7962687. PMID 33828760.

- ^ a b Wotring, V. E. (2012). Space Pharmacology. Boston: Springer. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4614-3396-5.

- ^ Graybiel, A; Knepton, J (August 1976). "Sopite syndrome: a sometimes sole manifestation of motion sickness". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 47 (8): 873–882. PMID 949309.

- ^ Matsangas, Panagiotis; McCauley, Michael E. (June 2014). "Sopite Syndrome: A Revised Definition". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 85 (6): 672–673. doi:10.3357/ASEM.3891.2014. hdl:10945/45394. PMID 24919391. S2CID 36203751.

- ^ T., Reason, J. (1975). Motion sickness. Brand, J. J. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-584050-7. OCLC 2073893.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Heer, Martina; Paloski, William H. (2006). "Space motion sickness: Incidence, etiology, and countermeasures". Autonomic Neuroscience. 129 (1–2): 77–79. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2006.07.014. PMID 16935570. S2CID 6520556.

- ^ Thornton, William; Bonato, Frederick (2017). The Human Body and Weightlessness. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-32829-4. ISBN 978-3-319-32828-7.

- ^ Space Pharmacology | Virginia E. Wotring. SpringerBriefs in Space Development. Springer. 2012. p. 59. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3396-5. ISBN 978-1-4614-3395-8.

- ^ Ploutz-Snyder, Lori; Bloomfield, Susan; Smith, Scott M.; Hunter, Sandra K.; Templeton, Kim; Bemben, Debra (November 2014). "Effects of Sex and Gender on Adaptation to Space: Musculoskeletal Health". Journal of Women's Health. 23 (11): 963–966. doi:10.1089/jwh.2014.4910. PMC 4235589. PMID 25401942.

- ^ a b c d e f g Narici, M. V.; de Boer, M. D. (March 2011). "Disuse of the musculo-skeletal system in space and on earth". European Journal of Applied Physiology. 111 (3): 403–420. doi:10.1007/s00421-010-1556-x. PMID 20617334. S2CID 25185533.

- ^ a b Smith, Scott M.; Heer, Martina; Shackelford, Linda C.; Sibonga, Jean D.; Spatz, Jordan; Pietrzyk, Robert A.; Hudson, Edgar K.; Zwart, Sara R. (2015). "Bone metabolism and renal stone risk during International Space Station missions". Bone. 81: 712–720. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2015.10.002. PMID 26456109.

- ^ Elmantaser, M; McMillan, M; Smith, K; Khanna, S; Chantler, D; Panarelli, M; Ahmed, SF (September 2012). "A comparison of the effect of two types of vibration exercise on the endocrine and musculoskeletal system". Journal of Musculoskeletal & Neuronal Interactions. 12 (3): 144–154. PMID 22947546.

- ^ Ramsdell, Craig D.; Cohen, Richard J. (2003). "Cardiovascular System in Space". Encyclopedia of Space Science and Technology. doi:10.1002/0471263869.sst074. ISBN 978-0-471-26386-9.

- ^ a b White, Ronald J.; Lujan, Barbara F. (1989). Current status and future direction of NASA's Space Life Sciences Program (Report).

- ^ Aubert, André E.; Beckers, Frank; Verheyden, Bart; Plester, Vladimir (August 2004). "What happens to the human heart in space? - Parabolic flights provide some answers" (PDF). ESA Bulletin. 119: 30–38. Bibcode:2004ESABu.119...30A.

- ^ Wieling, Wouter; Halliwill, John R.; Karemaker, John M. (January 2002). "Orthostatic intolerance after space flight". The Journal of Physiology. 538 (1): 1. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013372. PMC 2290012. PMID 11773310.

- ^ Stewart, J. M. (May 2013). "Common Syndromes of Orthostatic Intolerance". Pediatrics. 131 (5): 968–980. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2610. PMC 3639459. PMID 23569093.

- ^ Lillywhite, Harvey B. (1993). "Orthostatic Intolerance of Viperid Snakes". Physiological Zoology. 66 (6): 1000–1014. doi:10.1086/physzool.66.6.30163751. JSTOR 30163751. S2CID 88375293.

- ^ Nasoori, Alireza; Taghipour, Ali; Shahbazzadeh, Delavar; Aminirissehei, Abdolhossein; Moghaddam, Sharif (September 2014). "Heart place and tail length evaluation in Naja oxiana, Macrovipera lebetina, and Montivipera latifii". Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 7: S137 – S142. doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60220-0. PMID 25312108.

- ^ Stewart, Julian M. (December 2004). "Chronic orthostatic intolerance and the postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS)". The Journal of Pediatrics. 145 (6): 725–730. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.084. PMC 4511479. PMID 15580191.

- ^ Gunga, Hanns-Christian; Ahlefeld, Victoria Weller von; Coriolano, Hans-Joachim Appell; Werner, Andreas; Hoffmann, Uwe (2016-07-14). Cardiovascular system, red blood cells, and oxygen transport in microgravity. Gunga, Hanns-Christian,, Ahlefeld, Victoria Weller von,, Coriolano, Hans-Joachim Appell,, Werner, Andreas,, Hoffmann, Uwe. Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-319-33226-0. OCLC 953694996.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[page needed] - ^ Bungo, Michael (March 23, 2016). "Cardiac Atrophy and Diastolic Dysfunction During and After Long Duration Spaceflight: Functional Consequences for Orthostatic Intolerance, Exercise Capability and Risk for Cardiac Arrhythmias (Integrated Cardiovascular)". NASA. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ Fritsch-Yelle, Janice M.; Leuenberger, Urs A.; D'Aunno, Dominick S.; Rossum, Alfred C.; Brown, Troy E.; Wood, Margie L.; Josephson, Mark E.; Goldberger, Ary L. (June 1998). "An Episode of Ventricular Tachycardia During Long-Duration Spaceflight". The American Journal of Cardiology. 81 (11): 1391–1392. doi:10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00179-9. PMID 9631987.

- ^ Clément, Gilles (2011). Fundamentals of Space Medicine. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-9905-4. OCLC 768427940.[page needed]

- ^ "Mutant super-cockroaches from space". New Scientist. January 21, 2008. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016.

- ^ "Egg Experiment in Space Prompts Questions". New York Times. 1989-03-31. Archived from the original on 2009-01-21.

- ^ Caspermeyer, Joe (23 September 2007). "Space flight shown to alter ability of bacteria to cause disease". Arizona State University. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Kim W, et al. (April 29, 2013). "Spaceflight Promotes Biofilm Formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e6237. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...862437K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062437. PMC 3639165. PMID 23658630.

- ^ Dvorsky, George (13 September 2017). "Alarming Study Indicates Why Certain Bacteria Are More Resistant to Drugs in Space". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Dose, K.; Bieger-Dose, A.; Dillmann, R.; Gill, M.; Kerz, O.; Klein, A.; Meinert, H.; Nawroth, T.; Risi, S.; Stridde, C. (1995). "ERA-experiment "space biochemistry"". Advances in Space Research. 16 (8): 119–129. Bibcode:1995AdSpR..16h.119D. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(95)00280-R. PMID 11542696.

- ^ Horneck G.; Eschweiler, U.; Reitz, G.; Wehner, J.; Willimek, R.; Strauch, K. (1995). "Biological responses to space: results of the experiment "Exobiological Unit" of ERA on EURECA I". Adv. Space Res. 16 (8): 105–18. Bibcode:1995AdSpR..16h.105H. doi:10.1016/0273-1177(95)00279-N. PMID 11542695.

- ^ "Growing Crystals in Zero-Gravity".

- ^ "Published Results From Crystallization Experiments on the ISS Could Help Merck Improve Cancer Drug Delivery".

- ^ Reichert, Paul; Prosise, Winifred; Fischmann, Thierry O.; Scapin, Giovanna; Narasimhan, Chakravarthy; Spinale, April; Polniak, Ray; Yang, Xiaoyu; Walsh, Erika; Patel, Daya; Benjamin, Wendy; Welch, Johnathan; Simmons, Denarra; Strickland, Corey (2019-12-02). "Pembrolizumab microgravity crystallization experimentation". npj Microgravity. 5 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 28. Bibcode:2019npjMG...5...28R. doi:10.1038/s41526-019-0090-3. ISSN 2373-8065. PMC 6889310. PMID 31815178.

- ^ Koszelak, S; Leja, C; McPherson, A (1996). "Crystallization of biological macromolecules from flash frozen samples on the Russian Space Station Mir". Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 52 (4): 449–58. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19961120)52:4<449::AID-BIT1>3.0.CO;2-P. PMID 11541085. S2CID 36939988.

External links

[edit]![]() The dictionary definition of zero gravity at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of zero gravity at Wiktionary

![]() Media related to Weightlessness at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Weightlessness at Wikimedia Commons

- Microgravity Centre Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- How Weightlessness Works at HowStuffWorks

- NASA - SpaceResearch - Human Physiology Research and the ISS: Staying Fit Along the Journey

- "Why are astronauts weightless?" Video explanation of the fallacy of "zero gravity".

- Overview of microgravity applications and methods

- Criticism of the terms "Zero Gravity" and "Microgravity", a persuasion to use terminology that reflects accurate physics (sci.space post).

- Microgravity Collection, The University of Alabama in Huntsville Archives and Special Collections

- Space Biology Research at AU-KBC Research Centre

- Jhala, Dhwani; Kale, Raosaheb; Singh, Rana (2014). "Microgravity Alters Cancer Growth and Progression". Current Cancer Drug Targets. 14 (4): 394–406. doi:10.2174/1568009614666140407113633. PMID 24720362.

- Tirumalai, Madhan R.; Karouia, Fathi; Tran, Quyen; Stepanov, Victor G.; Bruce, Rebekah J.; Ott, C. Mark; Pierson, Duane L.; Fox, George E. (December 2017). "The adaptation of Escherichia coli cells grown in simulated microgravity for an extended period is both phenotypic and genomic". npj Microgravity. 3 (1): 15. doi:10.1038/s41526-017-0020-1. PMC 5460176. PMID 28649637.

![Protein crystals grown by American scientists on the Russian Space Station Mir in 1995.[82]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d1/Crystals_grown_in_microgravity.jpg/120px-Crystals_grown_in_microgravity.jpg)