Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vietic languages

View on WikipediaThis article should specify the language of its non-English content using {{lang}} or {{langx}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (July 2021) |

| Vietic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Mainland Southeast Asia |

| Linguistic classification | Austroasiatic

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Vietic |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | viet1250 |

Vietic | |

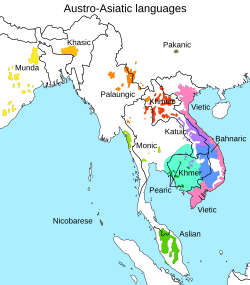

The Vietic languages are a branch of the Austroasiatic language family, spoken by the Vietic peoples in Laos and Vietnam. The branch was once referred to by the terms Việt–Mường, Annamese–Muong, and Vietnamuong; the term Vietic was proposed by La Vaughn Hayes,[1][2] who proposed to redefine Việt–Mường as referring to a sub-branch of Vietic containing only Vietnamese and Mường.

Many of the Vietic languages have tonal or phonational systems intermediate between that of Viet–Muong and other branches of Austroasiatic that have not had significant Chinese or Tai influence.

Origins

[edit]The ancestor of the Vietic language is traditionally assumed to have been located in today's North Vietnam.[3][4][5]

However, the origin of the Vietic languages remains a controversial topic among linguists. Another theory, based on linguistic diversity, locates the most probable homeland of the Vietic languages in modern-day Bolikhamsai Province and Khammouane Province in Laos as well as parts of Nghệ An Province and Quảng Bình Province in Vietnam. The time depth of the Vietic branch dates back at least 2,500 years to 2,000 years (Chamberlain 1998); 3,500 years (Peiros 2004); or around 3,000 years (Alves 2020).[6][7] Even so, archaeogenetics demonstrated that before the Đông Sơn period, the Red River Delta's inhabitants were predominantly Austroasiatic: genetic data from Phùng Nguyên culture's Mán Bạc burial site (dated 1,800 BC) have close proximity to modern Austroasiatic speakers such as the Mlabri and Lua from Thailand, the Nicobarese from India (Nicobar Islands), and the Khmer from Cambodia;[8][9] meanwhile, "mixed genetics" from Đông Sơn culture's Núi Nấp site showed affinity to "Dai from China, Tai-Kadai speakers from Thailand, and Austroasiatic speakers from Vietnam, including the Kinh";[10] therefore, "[t]he likely spread of Vietic was southward from the RRD, not northward. Accounting for southern diversity will require alternative explanations."[11]

Vietnamese

[edit]The Vietnamese language was identified as Austroasiatic in the mid-nineteenth century, and there is now strong evidence for this classification. Modern Vietnamese has lost many Proto-Austroasiatic phonological and morphological features. Vietnamese also has large stocks of borrowed Chinese vocabulary. However, there continues to be resistance to the idea that Vietnamese could be more closely related to Khmer than to Chinese or Tai languages among Vietnamese nationalists. The vast majority of scholars attribute typological similarities with Sinitic and Tai to language contact rather than to common inheritance.[12]

Chamberlain (1998) argues that the Red River Delta region was originally Tai-speaking and became Vietnamese-speaking only between the seventh and ninth centuries AD as a result of emigration from the south, i.e., modern Central Vietnam, where the highly distinctive and conservative North-Central Vietnamese dialects are spoken today. Therefore, the region of origin of Vietnamese (and the earlier Viet–Muong) was well south of the Red River.[13]

On the other hand, Ferlus (2009) showed that the inventions of pestle, oar and a pan to cook sticky rice, which is the main characteristic of the Đông Sơn culture, correspond to the creation of new lexicons for these inventions in Northern Vietic (Việt–Mường) and Central Vietic (Cuoi-Toum). The new vocabularies of these inventions were proven to be derivatives from original verbs rather than borrowed lexical items. The current distribution of Northern Vietic also corresponds to the area of Dong Son culture. Thus, Ferlus concludes that the Northern Vietic (Viet-Muong) is the direct heir of the Dongsonian, who had resided in the southern part of the Red River Delta and North Central Vietnam from the 1st millennium BC.[4]

Furthermore, John Phan (2013, 2016)[14][15] argues that “Annamese Middle Chinese” was spoken in the Red River Valley and was then later absorbed into the coexisting Proto-Viet-Muong, one of whose divergent dialects evolved into the Vietnamese language.[16] Annamese Middle Chinese belonged to a Middle Chinese dialect continuum in southwestern China that eventually "diversified into" Waxiang Chinese, the Jiudu patois (九都土話) of Hezhou, Southern Pinghua, and various Xiang Chinese dialects (e.g., Xiangxiang, Luxi, Qidong, and Quanzhou).[15] Phan (2013) lists three major types of Sino-Vietnamese borrowings, which were borrowed during different eras:

- Early Sino-Vietnamese (Han dynasty (ca. 1st century CE) and Jin dynasty (ca. 4th century CE) layers)

- Late Sino-Vietnamese (Tang dynasty)

- Recent Sino-Vietnamese (Ming dynasty and post-Ming dynasty)

Distribution

[edit]

Vietic speakers reside in and around the Nakai–Nam Theun Conservation Area of Laos and north-central Vietnam (Chamberlain 1998). Many of these speakers are referred to as Mường, Nhà Làng, and Nguồn. Chamberlain (1998) lists current locations in Laos for the following Vietic peoples.[17] An overview based on first-hand fieldwork has been proposed by Michel Ferlus.[18]

- Nguồn: Ban Pak Phanang, Boualapha District, Khammouane; others in Vietnam

- Liha, Phong (Cham), and Toum: Khamkeut District; probably originally from the northern Nghe An / Khamkeut border area

- Ahoe: originally lived in Na Tane Subdistrict of Nakai District, and Ban Na Va village in Khamkeut District; taken to Hinboun District during the war, and then later resettled in Nakai Tay (39 households) and in Sop Hia (20 households) on the Nakai Plateau.

- Thaveung (Ahao and Ahlao dialects): several villages near Lak Xao; probably originally from the Na Heuang area

- Cheut: Ban Na Phao and Tha Sang, Boualapha District; others probably also in Pha Song, Vang Nyao, Takaa; originally from Hin Nam No and Vietnam

- Atel: Tha Meuang on the Nam Sot (primarily Malang people); originally from the Houay Kanil area

- Thémarou: Vang Chang on the Nam Theun; Ban Soek near the Nam Noy

- Makang: Na Kadok, Khamkeut District (primarily Saek people); originally from the Upper Sot area

- Malang: Tha Meuang on the Nam Sot

- "Salang": Ban Xe Neua, Boualapha District

- Atop: Na Thone, Khamkeut District (primarily Tai Theng people); originally from the Upper Sot area

- Mlengbrou: near the Nam One; later relocated to the Yommalath District side of the Ak Mountain, and now living in Ban Sang, Yommalath District (primarily Yooy people)

- Kri: Ban Maka

In Vietnam, some Vietic hill-tribe peoples, including the Arem, Rục, Maliêng, and Mày (Cươi), were resettled at Cu Nhái (located either in western Quảng Bình Province or in the southwest of Hương Khê District in Hà Tĩnh Province). The Sách are also found in Vietnam.

The following table lists the lifestyles of various Vietic-speaking ethnic groups. Unlike the neighboring Tai ethnic groups, many Vietic groups are not paddy agriculturalists.

| Lifestyle | Vietic group |

|---|---|

| Small-group foraging nomads | Atel, Thémarou, Mlengbrou, (Cheut?) |

| Originally collectors and traders who have become emergent swidden sedentists | Arao, Maleng, Malang, Makang, Tơe, Ahoe, Phóng |

| Swidden cultivators who move every 2–3 years among pre-existing village sites | Kri |

| Combined swidden and paddy sedentists | Ahao, Ahlao, Liha, Phong (Cham), Toum |

Languages

[edit]The discovery that Vietnamese was a Mon–Khmer language, and that its tones were a regular reflection of non-tonal features in the rest of the family, is considered a milestone in the development of historical linguistics.[19] Vietic languages show a typological range from a Chinese or Tai typology to a typical Mon-Khmer Austroasiatic typology, including (a) complex tonal systems, complex phonation systems or blends; (b) C(glide)VC or CCVC syllable templates; monosyllabic or polysyllabic and isolating or agglutinative typology.[20][21]

- Arem: This language lacks the breathy phonation common to most Vietic languages, but does have glottalized final consonants.

- Cuôi: Hung in Laos, and Thô in Vietnam

- Aheu (Thavung): This language makes a four-way distinction between clear and breathy phonation combined with glottalized final consonants. This is very similar to the situation in the Pearic languages in which, however, the glottalization is in the vowel.

- Ruc, Sach, May, and Chưt: A dialect cluster; the register system is the four-way contrast of Aheu augmented with pitch.

- Maleng (Bo, Pakatan): Tones as in Ruc-Sach.

- Pong, Hung, Tum, Khong-Kheng

- Việt–Mường: Vietnamese and Mường. These two dialect chains share 75% of their basic vocabulary, and have similar systems of 5–6 contour tones. These are regular reflexes of other Vietic languages: The three low and three high tones correspond to voiced and voiceless initial consonants in the ancestral language; these then split depending on the original final consonants: Level tones correspond to open syllables or final nasal consonants; high rising and low falling tones correspond to final stops, which have since disappeared; dipping tones to final fricatives, which have also disappeared; and glottalized tones to final glottalized consonants, which have deglottalized.

Classification

[edit]Sidwell & Alves (2021)

[edit]Sidwell & Alves (2021)[22] propose the following classification of the Vietic languages, which was first proposed in Sidwell (2021).[23] Below, the most divergent (basal) branches listed first. Vietic is split into two primary branches, Western (corresponding to the Thavung–Malieng branch) and Eastern (all of the non-Thavung–Malieng languages).

The Thavung-Malieng group retains the most archaic lexicon and phonological features, while the Chut group merges *-r and *-l finals to *-l, along with the other northern languages.[23]

Sidwell & Alves (2021) propose that the Vietic languages had dispersed from the Red River Delta, based on evidence from loanwords from early Sinitic and extensive Tai-Vietic contact possibly dating back to the Dong Son period.[22]

Chamberlain (2018)

[edit]Chamberlain (2018:9)[25] uses the term Kri-Mol to refer to the Vietic languages, and considers there to be two primary splits, namely Mol-Toum and Nrong-Theun. Chamberlain (2018:12) provides the following phylogenetic classification for the Vietic languages.

Sidwell (2015)

[edit]Based on comparative studies by Ferlus (1982, 1992, 1997, 2001) and new studies in Muong languages by Phan (2012),[26] Sidwell (2015)[27] pointed out that Muong is a paraphyletic taxon and subgroups with Vietnamese. Sidwell's (2015) proposed internal classification for the Vietic languages is as follows.

Chamberlain (2003)

[edit]The following classification of the Vietic languages is from Chamberlain (2003:422), as quoted in Sidwell (2009:145). Unlike past classifications, there is a sixth "South" branch that includes Kri, a newly described language.

- Vietic

- North (Viet–Muong)

- Vietnamese

- Mường (according to Phan (2012), Mường is paraphyletic[28])

- Nguồn

- Northwest (Cuoi)

- West (Thavưng)

- Ahoe

- Ahao

- Ahlao

- Southeast (Chut)

- Cheut

- Rục

- Sách

- Mày

- Malieng

- (Arem ?)

- (Kata)

- Southwest (Maleng)

- Atel

- Thémarou

- Arao

- Makang

- Malang

- Maleng

- Tơe

- South (Kri)

- Kri

- Phóng

- Mlengbrou

- North (Viet–Muong)

Animal cycle names

[edit]Michel Ferlus (1992, 2013)[29][30] notes that the 12-year animal cycle (zodiac) names in the Khmer calendar, from which Thai animal cycle names are also derived, and were borrowed from a phonologically conservative form of Viet-Muong[clarification needed]. Ferlus contends that the animal cycle names were borrowed from a Viet-Muong (Northern Vietic) language rather than from a Southern Vietic language, since the vowel in the Old Khmer name for "snake" /m.saɲ/ corresponds to Viet-Muong /a/ rather than to Southern Vietic /i/.

| Animal | Thai name | Khmer IPA | Modern Khmer | Angkorian Khmer | Old Khmer | Proto-Viet-Muong | Vietnamese | Mường | Pong | Kari |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 鼠 Rat | Chuat (ชวด) | cuːt | jūt (ជូត) | ɟuot | ɟuot | *ɟuot | chuột | chuột[a] /cuot⁸/ | - | - |

| 牛 Ox | Chalu (ฉลู) | cʰlou | chlūv (ឆ្លូវ) | caluu | c.luː | *c.luː | trâu | tlu /tluː¹/[b] | kluː¹ | săluː² |

| 虎 Tiger | Khan (ขาล) | kʰaːl | khāl (ខាល) | kʰaal | kʰa:l | *k.haːlˀ | khái[c] | khảl /kʰaːl³/ | kʰaːl³ | - |

| 兔 Rabbit | Thɔ (เถาะ) | tʰɑh | thoḥ (ថោះ) | tʰɔh | tʰɔh | *tʰɔh | thỏ | thó /tʰɔː⁵/ | tʰɔː³ | - |

| 龍 Dragon | Marong (มะโรง) | roːŋ | roṅ (រោង) | marooŋ | m.roːŋ | *m.roːŋ | rồng | rồng /roːŋ²/ | - | roːŋ¹ |

| 蛇 Snake | Maseng (มะเส็ง) | mə̆saɲ | msāñ' (ម្សាញ់) | masaɲ | m.saɲ | *m.səɲˀ | rắn | thẳnh /tʰaɲ³/[d] | siŋ³ | - |

| 馬 Horse | Mamia (มะเมีย) | mə̆miː | mamī (មមី) | mamia | m.ŋɨa | *m.ŋǝːˀ | ngựa | ngữa /ŋɨa⁴/ | - | măŋəː⁴ |

| 羊 Goat | Mamɛɛ (มะแม) | mə̆mɛː | mamæ (មមែ) | mamɛɛ | m.ɓɛː | *m.ɓɛːˀ | dê[e] | bẻ /ɓɛ:³/ | - | - |

| 猴 Monkey | Wɔɔk (วอก) | vɔːk | vak (វក) | vɔɔk | vɔːk | *vɔːk | voọc[f] | voọc /vɔːk⁸/ | vɔːk⁸ | - |

| 雞 Rooster | Rakaa (ระกา) | rə̆kaː | rakā (រកា) | rakaa | r.kaː | *r.kaː | gà | ca /kaː¹/ | kaː¹ | kaː¹ |

| 狗 Dog | Jɔɔ (จอ) | cɑː | ca (ច) | cɔɔ | cɔː | *ʔ.cɔːˀ | chó | chỏ /cɔː³/ | cɔː³ | cɔː³ |

| 豬 Pig | Kun (กุน) | kao/kol | kur (កុរ) | kur | kur | *kuːrˀ | cúi[g] | củi /kuːj³/ | kuːl⁴ | kuːl⁴ |

- ^ squirrel

- ^ /klu:¹/ in Ferlus

- ^ Nghệ An dialect

- ^ Hòa Bình dialect; Sơn La /saŋ³/ in Ferlus

- ^ from Proto-Vietic *-teː, not from the same root as other words

- ^ Nghệ-Tĩnh dialectal; old nucleus /*ɔː/ would have become diphthong /uə/ (spelt "-uô-") in other dialects, e.g. Huế ruộng /ʐuəŋ˨˩ʔ/ vs. Nghệ-Tĩnh roọng /ʐɔːŋ˨˨/, both from Proto-Vietic *rɔːŋʔ 'paddy field'

- ^ archaic; still found in the compound-noun cá cúi 'pig-fish'

References

[edit]- ^ Hayes, La Vaughn H. (1982). "The mutation of *R in Pre-Thavung" (PDF). Mon-Khmer Studies. 11: 83–100. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ Hayes, La Vaughn H. (1992). "Vietic and Việt-Mường: a new subgrouping in Mon-Khmer" (PDF). Mon-Khmer Studies. 21: 211–228. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ Sagart, Laurent (2008), "The expansion of Setaria farmers in East Asia", Past human migrations in East Asia: matching archaeology, linguistics and genetics, pp. 141–145,

The cradle of the Vietic branch of Austroasiatic is very likely in north Vietnam, at least 1000km to the south‑west of coastal Fújiàn

- ^ a b Ferlus, Michael (2009). "A Layer of Dongsonian Vocabulary in Vietnamese". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 1: 105.

- ^ Alves, Mark (2019-05-10). "Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Chamberlain, J.R. 1998, "The origin of Sek: implications for Tai and Vietnamese history", in The International Conference on Tai Studies, ed. S. Burusphat, Bangkok, Thailand, pp. 97-128. Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University.

- ^ Alves 2020, p. xix.

- ^ Lipson, Mark; Cheronet, Olivia; Mallick, Swapan; Rohland, Nadin; Oxenham, Marc; Pietrusewsky, Michael; Pryce, Thomas Oliver; Willis, Anna; Matsumura, Hirofumi; Buckley, Hallie; Domett, Kate; Hai, Nguyen Giang; Hiep, Trinh Hoang; Kyaw, Aung Aung; Win, Tin Tin; Pradier, Baptiste; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Candilio, Francesca; Changmai, Piya; Fernandes, Daniel; Ferry, Matthew; Gamarra, Beatriz; Harney, Eadaoin; Kampuansai, Jatupol; Kutanan, Wibhu; Michel, Megan; Novak, Mario; Oppenheimer, Jonas; Sirak, Kendra; Stewardson, Kristin; Zhang, Zhao; Flegontov, Pavel; Pinhasi, Ron; Reich, David (2018-05-17). "Ancient genomes document multiple waves of migration in Southeast Asian prehistory". Science. 361 (6397). American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS): 92–95. Bibcode:2018Sci...361...92L. bioRxiv 10.1101/278374. doi:10.1126/science.aat3188. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 6476732. PMID 29773666.

- ^ Corny, Julien, et al. 2017. "Dental phenotypic shape variation supports a multiple dispersal model for anatomically modern humans in Southeast Asia." Journal of Human Evolution 112 (2017):41-56. cited in Alves, Mark (2019-05-10). "Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture". Conference: "Contact Zones and Colonialism in Southeast Asia and China's South (~221 BCE - 1700 CE)"At: Pennsylvania State University

- ^ McColl et al. 2018. "Ancient Genomics Reveals Four Prehistoric Migration Waves into Southeast Asia". Preprint. Published in Science. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/278374v1 cited in Alves, Mark (2019-05-10). "Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture". Conference: "Contact Zones and Colonialism in Southeast Asia and China's South (~221 BCE - 1700 CE)"At: Pennsylvania State University

- ^ Alves, Mark (2019-05-10). "Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture". Conference: "Contact Zones and Colonialism in Southeast Asia and China's South (~221 BCE - 1700 CE)"At: Pennsylvania State University

- ^ LaPolla, Randy J. (2010). "Language Contact and Language Change in the History of the Sinitic Languages." Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(5), 6858-6868.

- ^ *Chamberlain, James R. 1998. "The Origin of the Sek: Implications for Tai and Vietnamese History". Journal of the Siam Society 86.1 & 86.2: 27-48.

- ^ Phan, John. 2013. Lacquered Words: the Evolution of Vietnamese under Sinitic Influences from the 1st Century BCE to the 17th Century CE. Ph.D. dissertation: Cornell University.

- ^ a b Phan, John D. & de Sousa, Hilário. 2016. A preliminary investigation into Proto-Southwestern Middle Chinese. (Paper presented at the International workshop on the history of Colloquial Chinese – written and spoken, Rutgers University, New Brunswick NJ, 11–12 March 2016.)

- ^ Phan, John. "Re-Imagining 'Annam': A New Analysis of Sino–Viet–Muong Linguistic Contact" in Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, Volume 4, 2010. pp. 22-3

- ^ "Welcome to World Bank Intranet" (PDF).

- ^ Ferlus, Michel. 1996. Langues et peuples viet-muong. Mon-Khmer Studies 26. 7–28.

- ^ Ferlus, Michel (2004). "The Origin of Tones in Viet-Muong". In Somsonge Burusphat (ed.). Papers from the Eleventh Annual Conference of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2001. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona State University Programme for Southeast Asian Studies Monograph Series Press. pp. 297–313.

- ^ See Alves 2003 on the typological range in Vietic.

- ^ The following information is taken from Paul Sidwell's lecture series on the Mon–Khmer languages.[1]

- ^ a b Sidwell, Paul; Alves, Mark (2021). "The Vietic languages: a phylogenetic analysis". Journal of Language Relationship. 19 (3–4): 166–194. doi:10.31826/jlr-2021-193-405.

- ^ a b Sidwell, Paul (2021). "Classification of MSEA Austroasiatic languages". The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia. De Gruyter. pp. 179–206. doi:10.1515/9783110558142-011. ISBN 9783110558142. S2CID 242599355.

- ^ Alves, Mark J. (2021). "Typological profile of Vietic". The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia. De Gruyter. pp. 469–498. doi:10.1515/9783110558142-022. ISBN 9783110558142. S2CID 240883280.

- ^ Chamberlain, James R. 2018. A Kri-Mol (Vietic) Bestiary: Prolegomena to the Study of Ethnozoology in the Northern Annamites. Kyoto Working Papers on Area Studies No. 133. Kyoto: Kyoto University.

- ^ Phan, John. 2012. "Mường is not a subgroup: Phonological evidence for a paraphyletic taxon in the Viet-Muong sub-family." In Mon-Khmer Studies, no. 40, pp. 1-18., 2012.

- ^ Sidwell, Paul. 2015. "Austroasiatic classification." In Jenny, Mathias and Paul Sidwell, eds (2015). The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages, 144-220. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Phan, John D. 2012. "Mường is not a subgroup: Phonological evidence for a paraphyletic taxon in the Viet-Muong sub-family." Mon-Khmer Studies 40:1-18.

- ^ Ferlus, Michel. 1992. "Sur L’origine Des Langues Việt-Mường." In Mon-Khmer Studies, 18-19: 52-59. (in French)

- ^ Michel Ferlus. The sexagesimal cycle, from China to Southeast Asia. 23rd Annual Conference of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, May 2013, Bangkok, Thailand. <halshs-00922842v2>

Further reading

[edit]- Alves, Mark J. (2022). "The Ðông Sơn Speech Community: Evidence for Vietic". Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Asian Interactions. 19 (2): 138–174. doi:10.1163/26662523-bja10002. S2CID 247915528.

- Alves, Mark (2021). Alves, Mark; Sidwell, Paul (eds.). "Vietic and Early Chinese Grammatical Vocabulary in Vietnamese: Native Vietic and Austroasiatic Etyma versus Early Chinese Loanwords". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 15 (3): 41–63. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5778105. ISSN 1836-6821. [Papers from the 30th Conference of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society (2021)]

- Alves, Mark J. (2020). "Historical Ethnolinguistic Notes on Proto-Austroasiatic and Proto-Vietic Vocabulary in Vietnamese". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 13 (2): xiii–xlv. hdl:10524/52472.

- Alves, Mark. 2020. Data for Vietic Native Etyma and Early Loanwords.

- Alves, Mark J. 2016. Identifying Early Sino-Vietnamese Vocabulary via Linguistic, Historical, Archaeological, and Ethnological Data, in Bulletin of Chinese Linguistics 9 (2016):264-295.

- Alves, Mark J. 2017. Etymological research on Vietnamese with databases and other resources. Ngôn Ngữ Học Việt Nam, 30 Năm Đổi Mới và Phát Triển (Kỷ Yếu Hội Thảo Khoa Học Quốc Tế), 183–211. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Khoa Học Xã Hội.

- Alves, Mark J. (2003). Ruc and Other Minor Vietic Languages: Linguistic Strands Between Vietnamese and the Rest of the Mon-Khmer Language Family. In Papers from the Seventh Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, ed. by Karen L. Adams et al. Tempe, Arizona, 3–19. Arizona State University, Program for Southeast Asian Studies.

- Barker, M. E. (1977). Articles on Proto-Viet–Muong. Vietnam publications microfiche series, no. VP70-62. Huntington Beach, Calif: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Chamberlain, J.R. 2003. Eco-Spatial History: a nomad myth from the Annamites and its relevance for biodiversity conservation. In X. Jianchu and S. Mikesell, eds. Landscapes of Diversity: Proceedings of the III MMSEA Conference, 25–28 August 2002. Lijiand, P. R. China: Center for Biodiversity and Indigenous Knowledge. pp. 421–436.

- Miyake, Marc. 2014. Black and white evidence for Vietnamese phonological history.

- Miyake, Marc. 2014. Soni linguae capitis. (Parts 1, 2-4.)

- Miyake, Marc. 2014. What the *-hɛːk is going on?

- Miyake, Marc. 2013. A 'wind'-ing tour.

- Miyake, Marc. 2010. Muong rhotics.

- Miyake, Marc. 2010. A meaty mystery: did Vietnamese have voiced aspirates?

- Nguyễn, Tài Cẩn. (1995). Giáo trình lịch sử ngữ âm tiếng Việt (sơ thảo) (Textbook of Vietnamese historical phonology). Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Gíao Dục.

- Pain, Frederick (2020). ""Giao Chỉ" (Jiaozhi 交趾) as a Diffusion Center of Middle Chinese Diachronic Changes: Syllabic Weight Contrast and Phonologisation of Its Phonetic Correlates". Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies. 50 (3): 356–437. doi:10.6503/THJCS.202009_50(3).0001.

- Peiros, Ilia J. 2004. Geneticeskaja klassifikacija aystroaziatskix jazykov. Moskva: Rossijskij gosudarstvennyj gumanitarnyj universitet (doktorskaja dissertacija).

- Trần Trí Dõi (2011). Một vài vấn đề nghiên cứu so sánh - lịch sử nhóm ngôn ngữ Việt - Mường [A historical-comparative study of Viet-Muong group]. Hà Nội: Nhà xuất bản Đại Học Quốc Gia Hà nội. ISBN 978-604-62-0471-8

- Sidwell, Paul (2009). Classifying the Austroasiatic languages: history and state of the art. LINCOM studies in Asian linguistics, 76. Munich: Lincom Europa.

External links

[edit]- La Vaughn Hayes Vietic Digital Archives

- SEAlang Project: Mon–Khmer languages. The Vietic Branch

- Sidwell (2003)

- Endangered Languages of Mainland Southeast Asia

- RWAAI (Repository and Workspace for Austroasiatic Intangible Heritage)

- Vietic languages in the RWAAI Digital Archive

Vietic languages

View on GrokipediaHistorical Background

Early Recognition and Misclassifications

The affiliation of Vietnamese with the Austroasiatic family was initially proposed in the mid-19th century, based on lexical and structural parallels with Mon, as noted by Logan in 1852 and elaborated by Forbes in 1881 and Müller.[4] Despite these observations, Vietnamese's heavy Sinosphere lexical borrowing—estimated at 60-70% in core vocabulary—and tonogenesis process, which transformed original Austroasiatic registers into a six-tone system, led to persistent misclassifications through the early 20th century.[5] Some scholars, influenced by superficial phonetic resemblances and areal Tai-Kadai contacts, grouped it with Sino-Tibetan (e.g., as early as 1877 proposals) or Tai languages (formalized in 1912 classifications), treating it as an outlier or substrate-influenced Tai variety rather than a core Austroasiatic member.[6] [7] André-Georges Haudricourt's 1954 study, "De l'origine des tons en vietnamien," resolved key doubts by reconstructing tonogenesis as a secondary development from Austroasiatic word-final stops and aspirates (*-p, *-t, *-k evolving into falling tones; *-h, *-ʔ into rising tones), preserving underlying sesquisyllabic structures absent in Sino-Tibetan or Tai models.[8] This empirical demonstration, grounded in comparative phonology across Mon-Khmer languages, confirmed Vietnamese's retention of proto-Austroasiatic features like implosive stops and affixal morphology, countering earlier dismissals by French philologists who had excluded it from Austroasiatic on prosodic grounds.[4] Recognition of the broader Vietic branch—beyond isolated Vietnamese—emerged in the mid-20th century, initially as the Viet-Muong subgroup linking Vietnamese with Muong dialects spoken by approximately 1.5 million people in northern Vietnam.[9] David Thomas formalized "Viet-Muong" in 1966 to denote this cluster, based on shared innovations like tone splitting and vocabulary retention (e.g., proto-Vietic *məŋ for 'younger sibling').[9] However, early frameworks misclassified peripheral Vietic varieties (e.g., Chut, Thavung) as divergent Mon-Khmer outliers rather than coordinate branches, underestimating the group's internal diversity spanning 20+ languages and 4-5 million speakers.[3] Michel Ferlus's work in the 1970s (1974, 1975, 1979) corrected this by distinguishing Viet-Muong from "Verdic" (Chut-like) subgroups via phylogenetic markers, such as differential sesquisyllable preservation, establishing Vietic as a primary Austroasiatic branch divergent around 2000-1000 BCE.[3] The term "Vietic" itself, proposed by La Vaughn Hayes, expanded the scope to include these elements, avoiding narrower ethnolinguistic labels.[1]Establishment within Austroasiatic Family

The affiliation of the Vietic languages with the Austroasiatic family was first tentatively proposed in the mid-19th century through comparisons of basic vocabulary linking Vietnamese to Mon, as noted by James Richardson Logan in 1852, with subsequent support from scholars including Forbes (1881), Müller (1888), and Kuhn (1889).[4] Wilhelm Schmidt's foundational work in 1905–1906 established the broader Austroasiatic phylum, encompassing Mon-Khmer and Munda branches, but Vietnamese was often excluded or marginalized due to its divergent typology—characterized by sesquisyllabicity shifting to monosyllabism, extensive tonality, and heavy lexical borrowing from Chinese and Tai languages—which obscured shared innovations.[4][3] Henri Maspero's 1912 analysis further complicated matters by positing Vietnamese as a hybrid of Mon-Khmer substrates and dominant Tai elements, fueling debates that persisted into the mid-20th century.[4] A pivotal advancement came with Jean Przyluski's 1924 advocacy for Austroasiatic membership based on lexical evidence prioritizing core vocabulary over surface typology, yet full consensus required phonological insights.[3] André-Georges Haudricourt's 1953 paper explicitly classified Vietnamese within Austroasiatic, positioning it between the Palaung-Wa and Mon-Khmer groups through comparative grammar and vocabulary, while his 1954 study on tonogenesis demonstrated that Vietnamese's six tones evolved from Proto-Austroasiatic final stops and aspirates via register splitting, a process paralleled in other family members like Khmer.[4][5] This reconstruction addressed prior skepticism, such as Pinnow's 1959 reservations, by evidencing regular sound changes and retaining over 20% Austroasiatic etyma in modern Vietnamese despite Sinospheric influences.[4] By the 1960s, the Vietic branch—encompassing Vietnamese, Muong dialects, and peripheral languages like Chut and Arem—was formalized as a primary subgroup of Austroasiatic, with David Thomas's 1966 introduction of the "Viet-Muong" label acknowledging shared innovations such as implosive stops and vowel harmony remnants.[9] Subsequent reconstructions by Michel Ferlus (1974, 1979) and phylogenetic analyses refined internal structure, confirming Vietic's basal position via 200+ cognate sets, though debates on exact divergence timing (circa 2,000–2,500 years ago) persist based on glottochronology and archaeological correlates.[3][5] This establishment relied on empirical lexical and phonological data, overriding earlier typological biases, and remains uncontroverted in contemporary linguistics.[4]Geographical Distribution and Speakers

Core Regions in Vietnam and Laos

The core regions for Vietic languages, excluding the widespread Vietnamese, lie in the north-central provinces of Vietnam, including Thanh Hóa, Nghệ An, Hà Tĩnh, and Quảng Bình, where minority languages such as those in the Chutic and Aremic subgroups are spoken by small ethnic communities in the Annamite Range highlands.[10][3] These areas feature rugged terrain that has historically isolated Vietic-speaking groups, preserving linguistic diversity amid Austroasiatic expansion.[9] In Laos, Vietic languages are primarily concentrated along the border with Vietnam, particularly in Khammouane and Bolikhamxay provinces, encompassing upland districts like the Nakai-Nam Theun Conservation Area and adjacent highlands where languages such as Kri, Maleng, and Thavung are spoken by communities numbering in the hundreds to low thousands.[2][11][12] This distribution reflects prehistoric migrations and adaptations to forested, karst landscapes, with speakers often maintaining semi-nomadic lifestyles tied to foraging and swidden agriculture.[13] Cross-border continuity between Vietnamese and Laotian territories underscores the shared ethnolinguistic heritage, though political boundaries and development pressures have fragmented some communities, limiting intergenerational transmission in isolated pockets.[14][3]Demographic Patterns and Migration Influences

The Vietic languages are spoken primarily by over 86 million people, with Vietnamese accounting for the vast majority as the native language of approximately 85 million speakers in Vietnam.[1] Non-Vietnamese Vietic languages, including Muong and various Chutic and Aremic varieties, are spoken by roughly 1.5 million individuals, predominantly ethnic Muong comprising about 1.5% of Vietnam's population of 98 million. Smaller groups such as Thavung (around 800 speakers in Laos) and Ruc (fewer than 320 in Vietnam) represent endangered varieties with limited demographic vitality.[1] Geographically, Vietnamese dominates lowland regions across Vietnam, while Muong speakers are concentrated in the northwestern highlands near the Laos border. Other Vietic languages are confined to remote upland areas in north-central Vietnam (provinces like Thanh Hóa and Nghệ An) and adjacent central Laos (Khammouane and Bolikhamsai provinces), reflecting a pattern of highland isolation for minority groups amid lowland assimilation.[15] This distribution underscores a demographic gradient where Vietic linguistic diversity decreases from peripheral highlands toward the densely populated Red River Delta and coastal plains. Historical migrations have profoundly shaped these patterns, with Proto-Vietic speakers likely originating in the Annamite highlands along the Vietnam-Laos border around 2,500 years ago during the Iron Age.[3] Subsequent northward expansion of Vietnamese-speaking populations into the Red River Delta, driven by wet-rice agriculture and state formation from the first millennium BCE, led to demographic dominance and partial assimilation of pre-existing groups.[11] Highland Vietic communities, less affected by these lowlands migrations, persisted through relative isolation, though 19th-century conflicts and modern socioeconomic pressures have induced further displacements and language shift toward Vietnamese.[16]Linguistic Classification

Overview of Internal Subgrouping Debates

The internal classification of Vietic languages remains debated due to sparse documentation of many minority lects, reliance on phonological and lexical comparisons, and evolving methodologies from traditional subgrouping to computational phylogenetics. Early 20th-century work by French linguists like Robert Bazin and André-Georges Haudricourt established Vietic as a branch of Austroasiatic, initially emphasizing a close Viet-Muong core (encompassing Vietnamese and Muong varieties) as the most innovative subgroup, with peripheral languages like Thavung and Chut seen as more conservative relics preserving archaic features such as implosive stops and complex vowel systems.[14] This Viet-Muong-centric model, formalized in works like Hayes (1992), posited phonological evidence for distinct branches but often treated non-Viet-Muong languages as loosely affiliated, leading to critiques of oversimplification amid incomplete data.[14] Debates intensified in the late 20th century with proposals challenging the primacy of Viet-Muong. Michel Ferlus (1992) argued for a more fragmented structure, suggesting that languages like Arem and Chut form independent clades based on shared retentions of proto-Vietic sesquisyllables and tone-register splits, rather than direct descent from a Viet-Muong ancestor. Similarly, David Chamberlain's alternative groupings in the 1990s highlighted potential areal convergences influenced by Tai-Kadai substrates, questioning strict genetic hierarchies and proposing flatter networks for eastern Vietic varieties. These views underscored methodological tensions: phonological conservatism in hill languages (e.g., preservation of *C- prefixes) versus Vietnamese's heavy Sinitic borrowing and tonogenesis, complicating tree-based models. Recent advances, particularly Sidwell's iterative refinements from 2011 onward, incorporate broader lexical datasets and Bayesian inference to resolve ambiguities. A 2021 phylogenetic study by Sidwell and Alves analyzed cognate sets across 20+ lects, yielding five primary subgroups—Thavung-Malieng, Chut-Arem, Pong-Toum, Cuoi-Tho, and Viet-Muong—with a basal binary split separating western (e.g., Cuoi) from eastern branches, supported by high posterior probabilities (e.g., 0.98 for Viet-Muong coherence). This contrasts with earlier binary or ternary divides by emphasizing quantitative divergence metrics over impressionistic phonology, though critics note potential biases from uneven data coverage and the exclusion of undescribed isolates. Ongoing disputes center on whether such models adequately capture contact-induced innovations or if hybrid cladistic-areal approaches better reflect Vietic's mosaic history.[17][3]Phylogenetic Approaches (Sidwell 2021 and Later)

In 2021, Paul Sidwell and Mark Alves conducted a computational phylogenetic analysis of the Vietic languages using a 116-item basic vocabulary wordlist compiled from 29 lects, including representatives such as Vietnamese, various Muong varieties, Nguon, Cuoi, Tho, Pong, Toum, Arem, Ruc, May, Thavung, and Malieng, with Jahai (Aslian) and Khmu (Khmuic) as outgroups.[3] The dataset drew from prior reconstructions like Ferlus (2007) and incorporated cognate coding based on shared phonological forms, analyzed via SplitsTree software employing Bayesian inference alongside UPGMA and neighbor-joining methods to generate hierarchical clustering from lexical retention rates.[3] Supplementary historical phonological comparisons focused on Proto-Vietic syllable codas (*-h, *-s, *-r, *-l) to resolve ambiguities in lexical data.[3] The analysis yielded a binary tree topology positing Thavung-Malieng as the earliest-diverging branch, followed by an Eastern Vietic clade exhibiting a north-south gradient: northern Viet-Muong (including Vietnamese, Muong, and Nguon) as innovative, contrasting with more conservative southern subgroups—Pong-Toum (Phong, Toum, Liha), Cuoi-Tho, and Chut-Arem (Arem, Sach, Ruc, May).[3] This structure identifies five primary subgroups, challenging prior typological subgroupings by emphasizing lexical phylogenetics over shared innovations like tonogenesis.[3] Key findings indicate that syllable restructuring and the development of register-tone systems—hallmarks of Vietic divergence from Proto-Austroasiatic—occurred convergently and independently across these subgroups, rather than as inherited traits defining deeper clades.[3] Subsequent references to Vietic classification, such as in Alves (2024) on Vietnamese Austroasiatic substrate, continue to endorse this 2021 phylogeny without proposing revisions, underscoring its role as the benchmark for data-driven subgrouping amid ongoing debates on contact-induced convergence in Mainland Southeast Asia.[5] The approach prioritizes quantitative cognate density over impressionistic shared innovations, offering a testable model for future expansions with denser lexical or genomic correlates.[3]Alternative Proposals (Chamberlain and Others)

James R. Chamberlain proposed modifications to Vietic subgrouping in 1998, emphasizing lexical isoglosses from faunal terminology and geographical proximity to challenge earlier divisions like those separating "Viet-Muong" from other branches.[11] His scheme repositioned languages such as Kri and Phóng within a southern cluster, alongside Mlengbrou and others, arguing for closer ties based on shared innovations in specialized vocabulary rather than solely phonological criteria.[11] This approach contrasted with more phonology-driven classifications by highlighting conservative retentions in hunter-gatherer groups' lexicons, which he contended better reflected deep-time relationships amid contact influences.[3] In 2003, Chamberlain expanded this to a six-subgroup framework, delineating North (encompassing Viet-Muong varieties like Vietnamese and Mường), Northwest (Cuoi-related), West (Thavung cluster), and additional peripheral groups without specifying hierarchical depths, prioritizing ethnographic and lexical data over computational modeling.[2] He incorporated Nguồn tentatively into northern branches but excluded distantly related outliers like Nha Lang or Toum-Liha, based on limited shared innovations in core vocabulary.[18] This proposal underscored the role of ethnozoological terms—such as those for pythons or birds—as stable markers for subgrouping, given their resistance to borrowing compared to everyday lexicon affected by Tai or Sino-Tibetan substrates.[19] By 2018, Chamberlain refined his model into a Kri-Molic phylogram derived from faunal bestiaries across Vietic varieties, grouping Kri and Mol languages as a distinct subclade within southern Vietic due to unique semantic extensions and retentions (e.g., unmarked generics for fauna categories).[20] This evidence-based tree challenged broader phylogenetic trees by proposing non-monophyletic status for some traditional Chutic units, attributing divergences to ecological adaptations in Annamite forager communities rather than uniform drift.[21] Unlike quantitative Bayesian methods, Chamberlain's qualitative focus on domain-specific lexicon aimed to mitigate biases from uneven data availability in minority languages.[3] Other scholars, such as Gérard Diffloth in earlier correspondences cited by Chamberlain, advocated southeastern placements for Cheut dialects like Sách, aligning with phonological parallels but diverging on lexical weighting.[11] These alternatives collectively prioritize specialized comparative data and socio-ecological contexts over automated phylogenetics, arguing that the latter may overemphasize basic Swadesh-list items prone to horizontal transfer in multilingual highlands.[22] Empirical support from field-collected faunal glossaries thus informs debates on Vietic internal structure, though integration with Sidwell's datasets remains limited by methodological incompatibilities.[2]Inventory of Languages

Viet-Muong Cluster

The Viet-Muong cluster forms a coherent northeastern clade within the Vietic branch of Austroasiatic languages, comprising Vietnamese, the Muong lects, and Nguon.[3] Phylogenetic analyses using lexical data from 116-item wordlists confirm this subgrouping, supported by shared innovations in historical phonology such as coda developments and tonogenesis.[3] These languages exhibit monosyllabic morphemes, syllable structures of the form C₁(C₂)V(C₃) where C₂ is typically a liquid or glide, and complex tone systems ranging from 5 to 6 tones, marking them as the most innovative among northern Vietic varieties.[3] Vietnamese (tiếng Việt) serves as the primary language of this cluster, functioning as the official language of Vietnam with an estimated 86 million native speakers concentrated in the Red River Delta and coastal regions, alongside diaspora communities.[23] Its standardization emerged in the 20th century, drawing from northern dialects, though it incorporates heavy Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary from historical Chinese influence.[9] The Muong languages, spoken by approximately 1 million ethnic Muong people in mountainous northern and north-central Vietnam, including provinces such as Hòa Bình, Sơn La, Thanh Hóa, and Bình Phước, represent a dialect continuum rather than discrete languages.[24] Key lects include those from Hoa Bình, Sơn La, Thanh Hóa, and Bí, which retain more conservative phonological features compared to Vietnamese, such as fuller consonant inventories and less advanced monosyllabization.[3] While traditionally viewed as dialects of a single Muong language, some analyses propose internal subgrouping challenges, with potential paraphyly noted in earlier studies, though recent phylogenetics affirm their unity within Viet-Muong.[3] Nguon (also Nguồn), included in the Viet-Muong clade, is spoken by small communities in Vietnam's Quảng Bình Province and adjacent areas in Laos, with speaker numbers estimated at around 2,400 in Vietnam, rendering it endangered.[25] Lects such as Cò Lьем and Yên Thờ exhibit close lexical and phonological ties to Muong and Vietnamese, supporting the cluster's integrity through shared retentions from Proto-Vietic.[3]

Chutic and Aremic Languages

The Chut-Arem subgroup represents one of the eastern branches in the Vietic phylogenetic tree, characterized by phonological conservatism including the retention of sesquisyllables and archaic lexical items shared via five isoglosses, such as innovations for 'beast/udder' and 'nail/claw'.[26] This subgroup occupies the southernmost position among Vietic clades, branching after the Thavung-Malieng divergence and below Pong-Toum and Cuoi-Tho.[26] Chutic languages form a compact internal cluster within Chut-Arem, comprising Ruc (also known as Mụ Già or Rục), Sach, and May (or Mày).[26] These are spoken primarily by the Chứt ethnic group in the mountainous border regions of Quảng Bình Province, Vietnam, and Khammouane Province, Laos, with small populations totaling around 3,000 speakers across dialects as of early 2000s surveys.[1] Ruc, for instance, exhibits breathy voice and glottalized finals atypical in broader Vietic but retains proto-Vietic consonant clusters more faithfully than Vietnamese.[26] Arem, classified as lexically divergent yet potentially an aberrant Chut lect, is spoken by a tiny community of approximately 75 individuals straddling the Vietnam-Laos border near the Arem River in Quảng Trị and Quảng Bình provinces.[1] It stands out for lacking the breathy phonation prevalent in most Vietic languages while featuring glottalized final consonants and a unique tonal system derived from register splits, alongside frequent sesquisyllabic structures that preserve pre-Vietic morphological complexity.[27] Possible substrate influence from neighboring Katuic languages appears in Arem lexicon, such as terms for 'horn' and 'earth/soil'.[26] Both Chutic and Arem remain endangered, with limited documentation emphasizing their role as conservative repositories of proto-Vietic features lost in expansive varieties like Vietnamese.[26]Other Peripheral Varieties

The Thavung-Malieng subgroup represents a peripheral branch of Vietic languages characterized by retention of archaic phonological features, including a four-way register system distinguishing breathy, clear, creaky, and harsh voice qualities.[17] This subgroup includes Thavung (also known as Ahao, Ahlao, or So), spoken primarily in central Laos and adjacent Vietnamese provinces by small communities numbering fewer than 1,000 speakers as of recent surveys; Malieng, documented in Khammouane Province, Laos, and neighboring Vietnam with an estimated 200-300 speakers; Maleng (or Pakatan), found in the same border region with around 150 speakers; and Kri, a closely related variety in Laos.[17] These languages exhibit conservative lexicon and syllable structure, preserving sesquisyllabic forms and implosive consonants less common in core Vietic varieties.[17] The Pong-Toum subgroup encompasses northwestern Vietic varieties associated with the Tho ethnic group, including Tho (with dialects such as Toum, Liha, and Phong), spoken in northern Vietnam's midland and mountainous regions by approximately 1,500-2,000 individuals.[17][28] These languages display innovations in tone development and vowel harmony, diverging from proto-Vietic patterns through contact with Tai-Kadai languages, while retaining Austroasiatic core vocabulary. Phylogenetic analysis places Pong-Toum as a distinct clade, supported by shared lexical retentions not found in adjacent subgroups.[17] Cuoi-Tho varieties form another peripheral cluster, featuring Cuoi (or Cuối, including dialects like Cuoi Cham and Hung) spoken by the Cuoi people in Nghệ An and Hà Tĩnh provinces of Vietnam, with speaker populations estimated at under 1,000, and Tho Tou in Vietnam alongside related forms in Laos.[17][29] Cuoi languages preserve proto-Vietic final consonants and exhibit pronominal systems reflecting social hierarchies, with "Cuoi" itself denoting "human" in the autonym.[29] This subgroup shows binary splits in phylogenetic trees, indicating early divergence, and limited documentation highlights risks of endangerment due to assimilation pressures.[17][30]Phonological and Morphological Features

Proto-Vietic Reconstructions

Proto-Vietic phonology has been reconstructed through comparative analysis of daughter languages, revealing a system conservative relative to Proto-Austroasiatic but with innovations like glottalized rimes and sesquisyllabic structures in some etyma.[1] Key works include Ferlus (1991, 2007) on vocalism and lexicon, Nguyễn Tài Cẩn (1995) on overall phoneme inventory, and Sidwell's phylogenetic studies integrating phonological correspondences across subgroups such as Thavung-Malieng and Viet-Muong.[10][3] These reconstructions posit a proto-system without inherent tones, instead featuring voice registers (clear vs. breathy, tied to initial voicing) from which tonal splits later emerged in languages like Vietnamese via mergers of final consonants and vowel length contrasts.[1] Initial consonants included a full series of stops (voiceless unaspirated, aspirated, voiced, and implosives like *ɓ and *ɗ, preserved in Arem and other peripheral varieties), nasals, approximants, a lateral *l, trill *r, and sibilant *s, with reflexes showing lenition in Viet-Muong (e.g., implosives to nasals or approximants).[1][10] Final (coda) consonants featured stops *-p, *-t, *-c, *-k; nasals *-m, *-n, *-ŋ; glides *-w, *-y; and approximants *-l, *-r, with *-s and *-h subject to subgroup-specific shifts (e.g., *-s to fricative or affricate in Pong-Toum, *-h lost and contributing to glottalization or "heavy" tones in Viet-Muong).[3] Glottalization of rimes (*CVʔ) is reconstructed as proto-Vietic, appearing in etyma linking conservative subgroups like Thavung and Arem to Vietnamese exceptions, and distinguishing from non-glottalized finals that merged into open syllables or tones.[1] Vowel reconstruction draws on Proto-Viet-Muong patterns, positing a system of monophthongs (*i, *e, *ɛ, *a, *ə, *ɔ, *o, *u) with length distinctions and possible diphthongs emerging from vowel + final interactions, though diphthongs were absent or marginal in core proto-forms.[1] Registers modulated vowel realization, with breathy voice correlating to lower pitch precursors in daughter tones (e.g., Vietnamese's six tones from three register-tone pairs plus broken tone from glottalized finals).[1] Phonotactic constraints allowed sesquisyllables (minor presyllable + major syllable), reducing to monosyllables in Vietnamese through consonant cluster simplification and vowel syncope.[31] Lexical reconstructions exceed 1,200 etyma in Ferlus (2007), covering basic vocabulary with Austroasiatic retentions (e.g., rice agriculture terms) and innovations absent in other branches, such as shared Viet-Muong numeral roots or body-part terms reflecting ~75% cognate retention between Vietnamese and Muong.[3][1] These forms underpin subgrouping, with conservative retention in Thavung-Malieng (e.g., distinct -l/-r codas) vs. innovations in Viet-Muong (e.g., coda mergers into tones).[3] Morphological reconstructions remain tentative, indicating an isolating analytic structure with limited affixation, though presyllables may have served derivational roles before erosion.[1] Ongoing refinements incorporate Bayesian phylogenetics to weigh phonological data against lexical cognacy.[3]Register and Tonal Developments

Proto-Vietic is reconstructed with a binary register contrast, where high register (tense, clear phonation) developed from syllables with voiceless initial stops and low register (lax, breathy phonation) from those with voiced initial stops, reflecting a devoicing process that preserved the laryngeal distinction in the vowel. This register split parallels patterns in other Austroasiatic branches and predates full tonogenesis, with conservative Vietic varieties like Arem retaining breathy voice contrasts without developing distinct tones.[1] Tonogenesis in Vietic proceeded through the reanalysis of final consonants into pitch contours, superimposed on the registers. Final stops (-p, -t, -k) evolved into checked (short, glottalized) tones, while fricatives (-s, -h) yielded rising or falling contours; open syllables maintained level tones. In Viet-Muong languages, including Vietnamese, this yielded a six-tone system by combining three basic contours (level, rising/falling, checked) across the two registers, with Vietnamese tones huyền/ngã (low), sắc/hỏi (high), and nặng/not (checked) tracing to low-register origins and ngang/sắc/hỏi to high-register.[1] The process was influenced by contact with tonal Chinese during the Han period (206 BCE–220 CE), accelerating devoicing and tensification in presyllables. Peripheral Vietic subgroups exhibit arrested tonogenesis. Chutic languages like Sách, Rục, and May show four tones tied to register differences, with pitch distinctions emerging but not fully decoupling from phonation; for instance, low-register tones feature lower F1 (vowel aperture) than high-register counterparts.[1] Thavung and Malieng retain a four-way phonation-pitch system from registers and post-glottalization, without merger into six tones due to earlier loss of final fricatives.[1] These variations indicate divergent rates of register-to-tone conversion, with core Viet-Muong innovating toward contour tones while minorities preserve proto-features like implosives and glottal rimes.Conservatism in Minority Languages vs. Vietnamese Innovations

Minority Vietic languages, such as those in the Thavung-Malieng, Chut-Arem, and Pong-Toum subgroups, exhibit greater phonological and morphological conservatism compared to Vietnamese, preserving proto-Vietic features that Vietnamese has innovated away from through simplification and external influences. For instance, Thavung-Malieng languages retain a distinction between codas -r and -l, reflecting an archaic contrast lost in eastern Vietic branches where merger to -l occurred, whereas Vietnamese further simplified finals amid monosyllabization and tonal elaboration.[3] Similarly, Chut-Arem languages maintain coda -h as a segmental feature (e.g., in Arem and various Chut varieties), in contrast to its loss in Viet-Muong, where it was rephonologized into a tonal category contributing to Vietnamese's six-tone system.[3] These peripheral languages thus provide evidence of pre-tonal proto-Vietic phonology more akin to broader Austroasiatic patterns.[14] Morphologically, conservative Vietic varieties like Chut and Thavung retain sesquisyllabic word structures and vestiges of Austroasiatic affixation, such as prefixes and infixes, which Vietnamese has largely shed in favor of strict monosyllabism—a innovation likely accelerated by prolonged Sinitic contact and internal regularization.[3] Vietnamese's lexicon, while retaining core Austroasiatic roots, incorporates extensive early Chinese loans (estimated at 60-70% in basic vocabulary by some analyses), whereas minority Vietic languages show fewer such borrowings, preserving purer proto-Vietic terms and isoglosses (e.g., shared Chut-Arem forms for 'beast/udder' like Arem nɒːh and Sach nɔːj).[3] This conservatism in minority languages underscores Vietnamese's divergence, driven by lowland expansion, literacy via Sino-Vietnamese script, and sociolinguistic dominance, rendering it less representative of proto-Vietic typology.[14][32] Lexical retention in archaic Vietic subgroups further highlights Vietnamese innovations, as Ruc (a Chut language) preserves basic vocabulary and phonological reflexes unchanged from proto-Vietic, such as unaltered initial clusters, while Vietnamese exhibits mergers and tone splits absent in these isolates.[14] Overall, these patterns position minority Vietic languages as key to reconstructing proto-Vietic, revealing Vietnamese's trajectory toward analytic isolation amid areal pressures, rather than conservative continuity.[3]Lexical Characteristics

Austroasiatic Retentions

Vietic languages retain a core lexicon from Proto-Austroasiatic (pAA), comprising basic vocabulary in domains such as body parts, numerals, animals, and natural elements, which distinguishes them from heavy borrowing in areas like administration and technology.[5] In Vietnamese, approximately 66–75% of the lexicon is native Austroasiatic, with around 200 identifiable pAA etyma, including terms for everyday concepts that show regular phonological correspondences across the family.[5] Minority Vietic varieties, such as those in the Chut-Arem and Thavung-Malieng subgroups, often preserve more conservative forms, including sesquisyllabic structures and codas lost or rephonologized in Vietnamese.[3] Key retentions include body part terms: mắt 'eye' from pAA mat, shared with Muong măt and Phong mat; mũi 'nose' from pAA məʔrus, cognate with Muong mui and Phong muic; tóc 'hair' from pAA suk, matching Muong tʰak and Phong suk; tay 'hand/arm' with parallels in Muong tʰai and Phong si; cổ 'neck' linked to Muong kel/kok and Phong kiko; and cằm 'chin' from forms like Muong and Phong kăŋ.[33] Animal names also persist, such as Vietnamese chó 'dog' from pAA cɔʔ and chim 'bird' from pAA ciːm, with broader Austroasiatic matches in branches like Katuic.[5][3] Numeral systems in Vietic derive entirely from Mon-Khmer (Austroasiatic) roots, as established in early comparative work, reflecting deep retention of quantifying lexicon.[33] Terms for natural substances include nước 'water' from Proto-Vietic ɗa:k and gạo 'husked rice' from pAA rəŋ.koːˀ.[5][3] Morphological patterns, such as the causative derivation in chết 'to die' and giết 'to kill', preserve pAA verbal structures absent in neighboring families like Tai-Kadai.[33] These retentions underpin Vietic's phylogenetic position within Austroasiatic, with phonological reflexes like pAA voiceless stops correlating to upper-register tones in Vietnamese (tones 1, 3, 5).[5]Borrowings and Contact Effects

Vietnamese exhibits extensive lexical borrowing from Chinese, with Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary comprising a significant portion of its lexicon, estimated at up to 60-70% in formal registers, though basic core vocabulary remains predominantly Austroasiatic.[34] These loans date back over two millennia, reflecting prolonged historical contact during periods of Chinese domination from the 2nd century BCE to the 10th century CE, and include terms for administration, culture, and technology, such as quốc gia ('nation') from Middle Chinese kwək kæ ('country').[35] Grammatical influence is more limited but present, with Sino-Vietnamese elements contributing to classifiers and certain syntactic patterns, though Vietnamese grammar retains its analytic Austroasiatic structure.[36] In contrast, other Vietic languages, particularly those outside the Viet-Muong subgroup, show fewer early Sino-Vietnamese loans, indicating differential sociolinguistic contact where Viet-Muong speakers experienced greater exposure to Sinitic influence due to centralized political integration.[37] For instance, Mường dialects retain more conservative Austroasiatic lexicon with minimal Chinese strata compared to Vietnamese, preserving native terms for household and kinship that Vietnamese replaced with borrowings.[37] This disparity underscores how Vietnamese's role as a prestige language amplified borrowing propagation within Viet-Muong but limited diffusion to peripheral groups like Chutic or Aremic speakers. Contact with Tai-Kadai languages has introduced additional loans across Vietic, especially in non-Viet-Muong varieties, where terms for agriculture, fauna, and local ecology reflect areal exchange in Laos and northern Vietnam.[10] Vietnamese also incorporates Tai loans, identifiable by phonological patterns such as initial implosives or specific vowel shifts, often postdating Sino-Vietnamese strata and numbering in the hundreds for everyday vocabulary.[38] These borrowings highlight multilingual ecologies in the region, with limited evidence of phonological convergence but notable lexical enrichment in domains of shared subsistence practices. Overall, contact effects remain primarily lexical, preserving Vietic's phonological and morphological conservatism amid substrate influences.[10]Cultural and Sociolinguistic Dimensions

Animal Cycle Terminology

In Vietic languages, the duodenary cycle—comprising twelve animals associated with years in the traditional East Asian sexagenary calendar—predominantly features native terms derived from Proto-Viet-Muong roots, which denote actual fauna and preserve Austroasiatic lexical heritage.[39] These contrast with the Sino-Vietnamese abbreviations (e.g., tý for rat, sửu for ox) used in standard Vietnamese calendrical nomenclature, which directly transliterate Middle Chinese characters introduced via historical Sinic influence.[39] Minority Vietic varieties, such as Muong, Thavung, Maleng, Rục, and Pong, retain these indigenous designations for cycle reckoning, reflecting linguistic conservatism amid cultural assimilation of the cycle itself, likely transmitted from China between the 3rd and 8th centuries CE.[40] Proto-Viet-Muong reconstructions for the cycle's animals, as proposed by Michel Ferlus, include forms etymologically linked to everyday zoological vocabulary rather than abstract sinograms.[39] For instance, the rat is ɟuot (cf. Vietnamese chuột, Muong cuot), the buffalo/ox c.luː (Vietnamese trâu, Muong kluː¹), the hare/rabbit tʰɔh (Vietnamese thỏ, Muong tʰɔː⁵; Vietnamese innovates with mèo 'cat' for this position), the dragon m.roːŋ (possibly originally 'crocodile'; Vietnamese rồng, Muong roːŋ²), the snake m.səɲˀ (Vietnamese rắn), the horse m.ŋǝːˀ (Vietnamese ngựa), the goat m.ɓɛːˀ (Vietnamese dê), the monkey vɔːk (Vietnamese khỉ), the rooster r.kaː (Vietnamese gà), the dog ʔ.cɔːˀ (Vietnamese chó), and the pig g/kuːrˀ (Vietnamese lợn).[39] The tiger position aligns with Vietic terms like Proto-Vietic k.la or equivalents in Muong varieties, completing the set of twelve correspondences attested across the branch.[40]| Zodiac Position | Proto-Viet-Muong | Vietnamese Gloss | Muong Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | ɟuot | chuột | cuot |

| Ox/Buffalo | c.luː | trâu | kluː¹ |

| Tiger | k.la (approx.) | hổ (native) | kla |

| Rabbit/Hare | tʰɔh | thỏ (hare); mèo (cat innovation) | tʰɔː⁵ |

| Dragon | m.roːŋ | rồng | roːŋ² |

| Snake | m.səɲˀ | rắn | səɲ |

| Horse | m.ŋǝːˀ | ngựa | ŋəː |

| Goat | m.ɓɛːˀ | dê | ɓɛː |

| Monkey | vɔːk | khỉ | vɔk |

| Rooster | r.kaː | gà | kaː |

| Dog | ʔ.cɔːˀ | chó | cɔː |

| Pig | g/kuːrˀ | lợn | kuːr |

Language Vitality and Endangerment Risks

The Vietic language family exhibits stark contrasts in vitality, with Vietnamese serving as the national language of Vietnam and boasting over 85 million native speakers worldwide, maintaining institutional support through education, media, and government use, rendering it robust and expanding via diaspora communities.[41] In contrast, Muong dialects, spoken by approximately 1.3 million ethnic Muong people primarily in northern and north-central Vietnam, demonstrate relative stability as a first language within their communities, though intergenerational transmission faces pressures from Vietnamese dominance in formal domains like schooling and administration.[42] Minority Vietic languages, concentrated in remote mountainous regions of central Vietnam and adjacent Laos, confront severe endangerment risks due to small speaker populations, limited documentation, and accelerating language shift toward Vietnamese amid modernization, migration, and interethnic marriage. Languages in the Chut subgroup, such as Arem and Ruc, exemplify critical vulnerability: Arem has fewer than 20 fluent speakers remaining, classified as endangered by Ethnologue and critically endangered by UNESCO criteria due to near-absent transmission to younger generations.[43] Ruc, with around 250 speakers, is rated definitely endangered, spoken primarily by older community members with steady decline in usage.[44]| Language | Estimated Speakers | Vitality Status | Key Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arem | <20 | Critically endangered | Minimal transmission; elderly-only speakers[45][43] |

| Ruc | ~250 | Definitely endangered | Decreasing usage; partial community fluency[46][44] |

| Chut (general) | Hundreds | Endangered | Assimilation to Vietnamese; undocumented dialects[47] |